The health care quality improvement effort is international: all nations seek to apply new knowledge and new technology for the health of their populations. However, the environment within which this effort takes place differs remarkably. In Mexico, for example, total expenditure on health care is only 5.6% of the gross national product—compared with about 15% in the USA, 11% or 12% in Canada, and an average of 6.1% in the Latin American countries. Further, 52% of Mexican health care expenditures are out of pocket in a country where poverty is prevalent and many people postpone care.

Structurally, the health care system in Mexico is public and private. Mexico has 4000 hospitals. The 1000 public hospitals have 75% of the beds; 90% of the 3000 private hospitals have ≤20 beds, often as few as ≤5 beds. In fact, some “private hospitals” can hardly be considered hospitals at all, since they have no laboratories, radiography equipment, or even nurses. The system also includes 20,000 primary care facilities.

As soon as President Vicente Fox began his administration in December 2000, government leaders began working on a national strategy for improving health care. In this article, I discuss the health care challenges, the objectives of this particular strategy, and the progress made to date.

HEALTH CARE CHALLENGES

Equity is one of the 3 main challenges faced in the Mexican health care system. In Mexico, 40 million people have incomes below the poverty line, and most of them are very, very poor. In contrast, maybe 2% of the population is rich, so the gap is enormous. If one child is born in the native Indian part of the state of Chihuahua and another is born the same day in Monterey, those children immediately face inequities: the child born in Monterey has a 17-year longer life expectancy.

Based on high out-of-pocket expenditures and the prevalence of poverty, financial protection is another major challenge. Each year, around 3 million people in Mexico face catastrophic expenses due to major illnesses or injuries.

Finally, quality is a challenge. According to several surveys, the population perceives the quality of health care as being very low in both the public and private sectors. In 1994, 44% of survey respondents rated quality as the major health care problem, followed by insufficient resources (30%), limited access (11%), and high costs (9%) (1). Interestingly, when the survey was redone in 2000, cost exceeded quality as the major problem cited due to the economic problems the country faced in 1995. Nevertheless, with cost related to access, quality remains the number one issue when it comes to provision of health care services. Further, when 1304 citizens were asked if various public services were good or excellent, only 37% gave these ratings to health services. Health services received ratings higher than only one other department, police; ratings were lower than those of public schools, water and sewage services, telephone services, and public transportation (2).

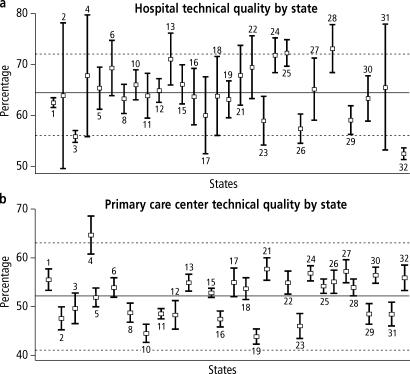

When technical quality is measured as an index based on several structure and process indicators, variations exist not only between states but also within states (Figure 1). Such variation implies that it is a matter of luck whether Mexicans receive good quality care. It depends on which state they live in, which hospital they go to, and even what time they arrive. In addition, the average level of quality is very low. Such results apply to more than just facilities of the Secretary of Health. From 1999 to 2001, 492 hospitals of different types were assessed for accreditation, and the trend of variation continued.

Figure 1.

Level of technical quality measured in facilities of the Mexican Secretary of Health in 32 states, 1997 to 2000. (a) Hospitals: n = 288, mean = 64, standard deviation = 8. (b) Primary care centers: n = 3047, mean = 52, standard deviation = 11. Data not shown for states 7, 9, 14, and 20. Source: Ministry of Health. Continuous Quality Improvement Program in Health Care.

THE NATIONAL HEALTH PROGRAM

To address the three challenges, the National Health Program was developed. This program has the following objectives:

To diminish inequalities in health (3 corresponding strategies)

To ensure fair financing (1 corresponding strategy)

To strengthen the health care system (5 corresponding strategies)

To improve the health status and to improve responsiveness (1 corresponding strategy: the National Crusade for Quality in Health Care)

The governmental division that I lead, called the Under secretary for Innovation and Quality, is responsible for all the objectives. This undersecretary division is one of 4; the other 3 deal with finance and administration; relationships with other public health care providers, congress, and state governments; and health promotion and disease control. Within the Undersecretary for Quality and Innovation, there are 3 branches: Quality and Education, Equity and Development, and Financial Protection. The undersecretary employs 1000 workers at the central level in Mexico City, 7000 workers in the states, and 14,000 interns and residents.

I now wish to focus on the quality crusade. The term “crusade” was chosen because its meaning incorporates the elements of vigor and a concerted action. Joint action is critical: the problem concerns not only the Secretary of Health or the private sector, but the entire country. To date, 4 public entities and about 20 private entities (including national academies, associations, and educational organizations) have joined the crusade. The idea is to get the ownership of all involved so that the crusade charges forward regardless of government support.

The crusade's general objectives are to improve the quality of care, to substantially decrease variations throughout the system, and to improve perceptions; these objectives are focused on the users, the health care organizations, the health care system as a whole, and the general population. Social endorsement of efforts is key.

A smile was chosen as a visual image of the crusade for a number of reasons. First, the “RIA” of its Spanish term, sonria (smile), becomes an acronym for the objectives of responsiveness and improving health status: respect (respeto), information (información), and kindness (amabilidad) for improving responsiveness, and outcomes (resultados), indicators (indicadores), and effective care (atención medica effectiva) for improving health status. Dimensions are called the “3 Es”: effective, efficient, ethical, and safe. Second, the smile image itself is significant. We want to see smiles from consumers and from providers. Achieving actual smiles will be tough, because resources and cultural changes are needed. The crusade is a long-term effort, but it must be started right away. What was done in the past lacked coordination and continuity.

The crusade has a long-term vision (for 2025) and a short-term vision (for 2006). By 2006, the crusade hopes to achieve explicit recognition of quality within the culture of health care organizations and evidence of improvement throughout the country that is clearly perceived by users, providers, and the entire population. In addition, the crusade has 3 strategies. The first is a thrust to change. New paradigms need to be developed and new work environments created. Continuous learning is a part of this, so it is another strategy. All efforts must be sustained over time, so sustainability is the third strategy. Seventy lines of action are associated with these strategies. They can be summarized in the following 10 overarching efforts:

Codes of ethics

Education for and of quality

Information towards and from the users, on and for improvement

Continuous quality improvement processes

Incentives

Process standardization and monitoring

Outcome monitoring

Accreditation of institutions and certification of providers

Regulation

Social participation

All participating institutions have identified 50 outcome measures that they would like to see assessed. Some of these were chosen for immediate testing, as discussed in the next section.

PROGRESS

Progress has already been made on several of the lines of action. For example, a nursing code of ethics has been developed and incorporated into hospitals and nursing schools. The patients' rights element of a physician code of ethics has been prepared. An agreement has been made with the Mexican Association of Schools of Medicine: the Secretary of Health hospitals will no longer accept students from schools that are not accredited; neither will students be allowed to have internships in hospitals that are not accredited. Similar arrangements will be made with nursing schools and dental schools. Accreditation in Mexico is relatively new; hospitals have been accredited for 4 years and medical schools for 8 years.

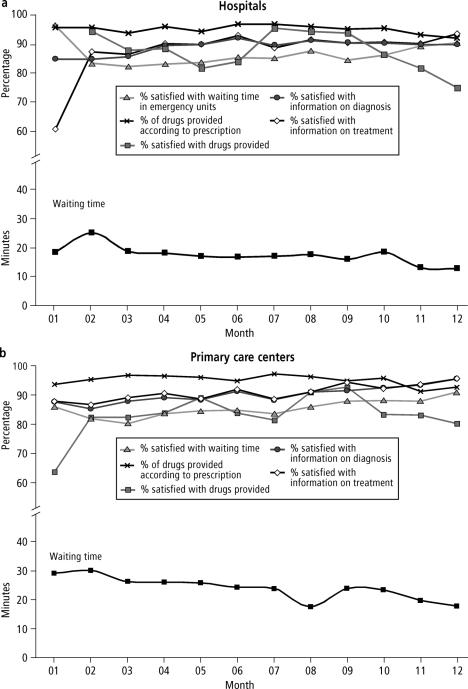

Beyond this, several indicators have been measured. Results tabulated from 2750 primary care units and 250 hospitals (about 25% of public-sector entities) in 29 of 31 states showed that waiting times in primary care and emergency services declined an average of 8 minutes, with patient satisfaction with waiting improved to an average of 85%; and better information was provided to patients on diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment, with 90% reporting satisfaction with the information provided (Figure 2). However, another indicator—satisfaction with the drugs provided and percentage of drugs provided according to prescrip-tion—did not show much improvement. These indicators were chosen because they were specifically listed as concerns of the population. They were also considered relatively easy to measure at a time when providers needed to learn how to measure. There have been some doubts about the reliability of data collected. The data on waiting times agree with data on satisfaction with waiting times, offering a type of internal verification. On the other hand, it is surprising that satisfaction with information provided to patients should be as high as it appears. Progress is also shown in results of a patient survey and provider survey conducted in May 2001. A total of 81% of patients and 78% of providers indicated that they thought the crusade would lead to much better or better quality of care. Thus, expectations are very high. Another survey asked patients in what aspects they have noted change: 48% cited kinder health care personnel, 15%, better organization; 12%, better schedules for appointments; 11%, better facility maintenance; and 7%, a cleaner facility. Interestingly, respondents mentioned areas that weren't even being addressed in the crusade, such as appointment schedules and facility maintenance. Perhaps when patients are treated better, they begin to view other aspects of health care more favorably as well. A final survey conducted on behalf of the Office of the President of Mexico asked citizens if the quality of care was better compared with the previous trimester. Between 16% and 31% of respondents had indicated some improvements in the 3 trimesters of 2001 with regard to waiting time, kindness from physicians and nurses, kindness from administrative personnel, supply of drugs, conditions of facilities, and availability of medical equipment.

Figure 2.

Results in (a) hospitals and (b) primary care centers on quality indicators measured in the first phase of the crusade.

The undersecretary plans to address additional indicators related to prenatal care, management of diabetes in primary care, management of diarrhea in children under 5 years of age in primary care, management of respiratory infections in children under 5 years of age in primary care, delivery care, and hospital infection rate.

Although quality and satisfaction are low in some instances, they are improving. A long period of time will be needed to make the necessary improvements and restore the confidence of the population. The crusade is an important step in this direction.

References

- 1.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black D, Morris JN, Smith C, Townsend P, Townsend P, Davidson N, editors. Inequalities in Health: The Black Report. Middlesex: Penguin; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Inequality in education, income, and occupation exacerbates the gaps between the health “haves” and “have-nots.”. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:60–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeHaven MJ, Hunter IB, Wilder L, Walton JW, Berry JD. Health partnerships in congregations: are they a remedy for the underserved? Presented at the 129th American Public Health Association Annual Meeting and Exposition. Atlanta, Ga: October 21–25, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger PL, Neuhaus RJ, Novak M, editors. To Empower People: From State to Civil Society. Washington, DC: AEI Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaves M, Tsitsos W. Congregations and social services: what they do, how they do it, and with whom. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 2001;30:660–683. [Google Scholar]