Abstract

Members of the cathelicidin family are present in all mammals studied. Generally, these proteins contain a conserved N-terminal domain and a structurally and functionally divergent C-terminal region that expresses antibacterial or other activities when proteolytically released. Rabbit granulocytes produce CAP18, a cathelicidin that conforms to this structural and functional organization, and also 15-kDa protein isoforms (p15s) that share several key structural features with other cathelicidins but apparently do not undergo processing with release of an active peptide. To further define the importance of proteolysis in the antibacterial activities of these proteins, we have purified from granulocytes proCAP18, its C-terminal peptide (CAP18p), and two p15 isoforms to apparent homogeneity. Of these four polypeptides, only CAP18p was independently cytotoxic to encapsulated Escherichia coli (90% inhibitory concentration, ∼600 nM) but it was ∼50-fold less potent on a molar basis than the bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (BPI). However, all four cathelicidin species, notably including proCAP18, exhibited antibacterial synergy with BPI, and the p15s also displayed synergy with CAP18p in the absence of BPI. Subnanomolar concentrations of proCAP18 blocked lipopolysaccharide-induced chemiluminescence of human leukocytes, showing a molar potency more than 100-fold greater than that of CAP18p (∼20 nM) or BPI (∼50 nM). Thus, while independent bactericidal activity of cathelicidins requires processing, other host-defense functions do not and are more potently expressed by the unprocessed protein than by the C-terminal peptide.

The preformed antimicrobial polypeptides of the polymorphonuclear granulocytes provide essential first-line defenses against microbial infection. While many innate defense polypeptides are active directly, for example, the bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (BPI) and lysozyme (4), several classes have been reported to require proteolytic processing for biological activity, e.g., defensins (16, 27) and cathelicidins (33, 34). Since many antimicrobial polypeptides also affect host cell functions (17, 20), proteolytic activation presumably serves to limit dysregulated expression of these activities and autotoxicity. Most cathelicidin family members have been cloned as cDNAs, and in accordance with the belief that the antimicrobial peptide contains all determinants of cathelicidin function, testing for antibacterial and other activities has been generally limited to synthetic C-terminal peptides (25, 26). An exception is the bactenecin family. In seminal studies on cathelicidin processing, Scocchi et al. and Zanetti et al. purified the proforms of Bac5 and Bac7 and showed that each lacks independent antimicrobial activity in contrast to the relatively potent C-terminal peptides produced during cellular activation (21, 33, 34).

Several isoforms of 15-kDa proteins have been purified and cloned from rabbit granulocytes and shown to neutralize lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and exhibit antimicrobial synergy with BPI (11, 12, 18). Hirata et al. and Larrick et al. isolated a bioactive peptide, and upon cloning its cDNA, they reported that this peptide (called CAP18p) corresponded to residues 106 to 142 of the proform referred to as proCAP18 (7, 10). The antimicrobial and LPS-neutralizing activities of CAP18p have been well characterized, but the preparations used in these studies and described as the parental form (proCAP18) were apparently at least partly processed since the sequence derived from Edman degradation corresponded to that of the C-terminal peptide (7, 10). Thus, unprocessed native proCAP18 has not yet been isolated and characterized.

In light of previous studies showing potent antimicrobial synergy among some of these proteins (12), a first requirement was to ensure that such analysis was not confounded by contamination of the individual agents with each other. It was therefore necessary to improve the methods for the purification to apparent homogeneity of the agents under study. For the first time, proCAP18 and its C-terminal peptide (CAP18p) could be resolved from each other and also from the cathelicidin-related p15A and p15B. By biochemical, immunological, and bioactivity criteria, cross-contamination of the purified proteins was ≤0.1%, allowing reliable analysis of some of their actions.

The results show that in contrast to the prevailing view, cathelicidin proforms can be potent participants in host defense against infectious agents, especially in complex settings wherein synergy among antimicrobial polypeptides is an important determinant of their effectiveness.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Purification of proteins.

Rabbit peritoneal polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNL) were isolated as described previously (35) and then stored at −20°C. All rabbit protocols were approved by an institutional review board. To extract cationic proteins from PMNL, the cells were diluted to 3 × 108 cells/ml of chilled water containing Pefabloc (Boehringer Mannheim) and disrupted at 4°C in a motor-driven Potter-Elvjhem homogenizer or in a Fisher sonic dismembranator at high power for 4 bursts of 30 s each in an ice bath. To the aqueous homogenate, a two-thirds volume of 0.4 N H2SO4 (final concentration, 0.16 N) was added while mixing. After a 30-min incubation at 4°C with intermittent mixing, the extract was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. Depending on the protein to be purified, the supernatant was dialyzed in a Spectrapor 3.5-kDa cutoff membrane against 4 liters of either 1 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5 for 4 days with 2 to 3 changes per day (for BPI or p15s) or 20 mM sodium acetate buffer at pH 4.0 with several changes overnight (for BPI, p15s, proCAP18, and CAP18 peptide). The acid extract was centrifuged as before, and the supernatant was transferred to polypropylene tubes for storage.

FPLC.

Fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) was performed with sulfonyl propyl (SP)-Sepharose (Fast Flow; Pharmacia). After loading proteins onto the column, bulk protein was eluted by washing with 1 M NaCl buffered with either 1 mM Tris, pH 7.5, or 20 mM acetate, pH 4.0, until absorbance monitored at 254 nm returned to the baseline. Then a gradient to 3 M NaCl-20 mM acetate, pH 4.0, was used to elute proCAP18, CAP18p, p15s, and BPI.

RP-HPLC.

After dialysis (to prevent precipitation of polypeptides in high salt), samples were loaded onto a butyl reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) column equilibrated in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). After washing of the column, proteins were eluted by a gradient of acetonitrile-0.1% TFA. Eluted proteins were either dialyzed against 20 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.0 (BPI), or lyophilized in a Savant vacuum centrifuge and then resuspended and stored in 20 mM acetate buffer at pH 4.0. To permit complete resolution of the CAP18 peptide from p15s, a second RP-HPLC chromatographic step was added by using a C4 column and a complex gradient from buffer A (0.1% TFA) to buffer B (47.5% acetonitrile-47.5% 2-propanol-5% water-0.085% TFA).

SDS-PAGE.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed by using the Pharmacia PhastGEL automated electrophoresis system according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunodetection of BPI, p15, and CAP18.

Proteins were transferred to 0.2-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher and Schuell) by the standard semidry technique with 48 mM Tris, 39 mM glycine, 20% methanol, and 0.0375% SDS. The membrane was air dried, blocked for at least 30 min in 2% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then placed in 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS with dilutions of primary antisera for 1 h at room temperature (RT) with shaking. Goat anti-rabbit BPI and guinea pig anti-rabbit p15 antisera have been described previously (29, 35). For the detection of rabbit CAP18 polypeptides, an antiserum was raised in goats immunized with synthetic Cys-tagged rabbit CAP18p conjugated with maleimide-activated keyhole limpet hemocyanin (Pierce). Blots were washed for 15 min in PBS with at least four changes, placed in antibody diluent with a 1:1,000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase (HRPO)-conjugated protein G or an HRPO-conjugated mouse anti-goat antibody (Pierce), and incubated for at least 20 min at RT with shaking. The blots were washed 5 times for 5 min each in PBS, and metal-enhanced diaminobenzidine (Pierce) was used to visualize HRPO conjugates. Normal goat serum or normal guinea pig serum did not significantly react with parallel blots.

Synthesis of peptides.

Solid-phase synthesis was performed using an Applied Biosystems model 433A peptide synthesizer as described elsewhere (26).

Edman degradation.

Primary sequences were determined by conventional Edman sequencing in the gas phase by employing an Applied Biosystems Procise instrument.

Protein quantitation.

The protein concentration and purity of stocks were determined by integration of HPLC chromatograms generated at a wavelength of 214 nm and by comparison with standards of known concentration by using Beckman Gold Nouveau software. Alternatively, concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Cyanogen bromide cleavage.

To allow sequencing of N-terminally blocked proCAP18 by Edman degradation, the protein was incubated in 75% formic acid with a 100-fold molar excess of cyanogen bromide dissolved in acetonitrile. After 24 h at RT in the dark, the reaction was terminated with water and the resulting peptides were lyophilized and resuspended in water and dried again (repeated twice) to remove residual CNBr.

Bioluminescence assay of bacterial viability.

Serum-resistant K1-encapsulated Escherichia coli K1/r with a rough LPS phenotype (kindly provided by Alan Cross, University of Maryland) (1) was transformed with pCGLS1 (5), a plasmid containing the bacterial luciferase of Xenorhabdus luminescens (generously provided by E. Peter Greenberg, University of Iowa), conferring a bioluminescent phenotype on ampicillin-selected bacteria. Transformants were subcultured (1:50) directly from an overnight culture and grown in tryptic soy broth containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) at 37°C with agitation until mid-log phase (about 3 to 4 h). Subcultures were centrifuged at 600 × g for 2 min, and the pellet was resuspended in sterile saline. The bacterial concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at 550 nm, and the bacteria were added to Hanks' balanced salt solution without divalent cations [HBSS(−)] supplemented with 0.3% Casamino Acids and buffered with 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4. Bacterium-containing test medium (90 μl) was placed in black polypropylene 96-well plates (Uniplate no. 7701-7350; Whatman Polyfiltronics, Clifton, N.J.) to which 10-μl protein dilutions or buffer was added, and luminescence was measured at 37°C in a Lucy I luminometer (Anthos) with intermittent agitation over 2 h. Data presented are expressed relative to untreated control bacteria.

LPS-induced leukocyte chemiluminescence.

Human venous blood was collected after informed consent was obtained, and the blood was diluted immediately into pyrogen-free dextran in HBSS(−) to a final concentration of 1% dextran and allowed to sediment at RT for 30 min. The leukocyte-rich supernatant was removed and washed twice in HBSS(−) and pelleted at 100 × g for 5 min at 18°C. Leukocytes were counted in a hemocytometer, diluted to a concentration of 1 × 106/ml of HBSS with divalent cations [HBSS(+)] buffered with 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, and supplemented with 1% human serum albumin and 30 μM lucigenin (bis-N-methylacridinium nitrate; Sigma). Recombinant LPS binding protein (LBP) (a kind gift of Xoma, Ltd., Berkeley, Calif.) was added to a concentration of 10 nM. Five microliters of protein diluted in 20 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.0, or buffer alone was added to 90 μl of cells prealiquoted in black polypropylene 96-well plates. To these cells, 5 μl of sonicated LPS [E. coli J5, Rc chemotype (List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, Calif.) diluted in HBSS(−) and supplemented with 1% human serum albumin] was added. Luminescence was measured for 5 s every 10 min at 37°C in a Lucy I luminometer.

RESULTS

Purification and identification of rabbit cathelicidins.

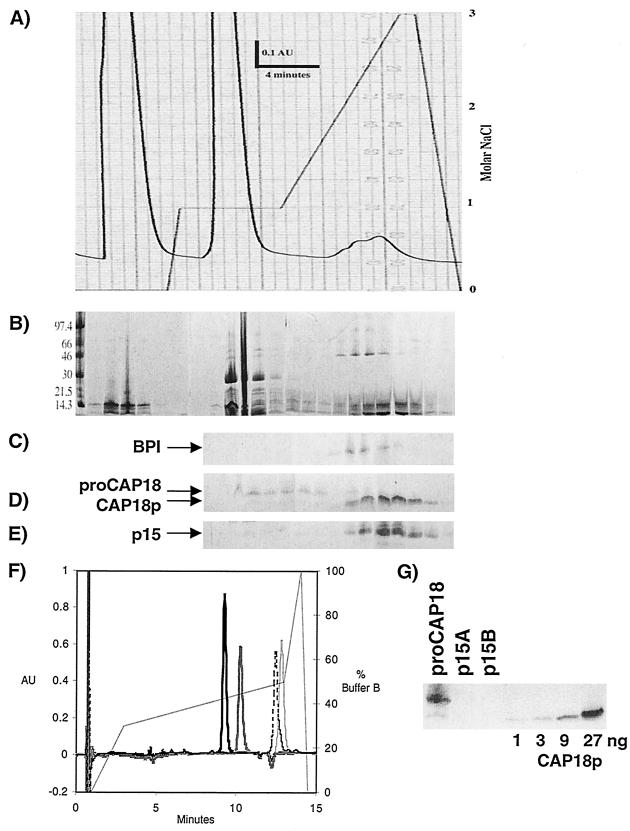

The first goal was to purify each of four species of cathelicidins from rabbit PMNL: proCAP18, CAP18p, p15A, and p15B. Sulfuric acid extraction of PMNL permits recovery of p15s and BPI in high yields (18, 31). Freshly collected rabbit peritoneal exudate leukocytes (>90% PMNL) contained p15s and proCAP18 but little or no CAP18p. However, some conversion of proCAP18 to CAP18p occurred during acid extraction and subsequent dialysis, allowing both proCAP18 and CAP18p to be recovered. Ion-exchange chromatography of dialyzed extracts on SP-Sepharose and a multistep NaCl gradient (Fig. 1A) first allowed separation of proCAP18 from >95% of the extracted protein that eluted at <1 M NaCl and then from the more cationic BPI (Fig. 1C), CAP18p (Fig. 1D), and p15s (Fig. 1E) that eluted later at higher NaCl concentrations (1.5 to 2 M). Further purification of each of the cathelicidins was accomplished using RP-HPLC on a butyl silica column as described in Materials and Methods, resulting in the purified protein species shown in Fig. 1F.

FIG. 1.

Purification of rabbit cathelicidins. (A) FPLC separation of cathelicidins by employing an SP-Sepharose column and a complex gradient of NaCl (solid line). (B) FPLC fractions were trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitated, resolved on gradient SDS-PAGE PhastGEL, and stained with Coomassie blue. Molecular mass standards (in kDa) are indicated on the left edge of the gels. Immunoblots of TCA-precipitated FPLC fractions were probed for BPI (C), CAP18 forms (D), and p15s (E). (F) Further resolution of proteins from FPLC fractions was accomplished by RP-HPLC with a C4 column and a complex acetonitrile gradient, as shown by the solid line. The figure is a composite of individual chromatograms of each purified protein run separately and detected at 214 nm (with background subtracted). The most hydrophilic protein, p15A, is the first to elute (heavy solid line), followed by p15B (gray solid line), CAP18p (dotted line), and proCAP18 (light solid line). (G) Immunoblots of proCAP18 and p15 isoforms (1 μg each) probed with antiserum against CAP18p.

For each protein species, purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE, RP-HPLC, and immunoblot analyses. proCAP18 was presumptively identified by electrophoretic migration during SDS-PAGE and reaction with goat-anti-rabbit CAP18p serum (Fig. 1D and G). The recovered protein was refractory to amino acid sequence analysis, indicating a blocked N terminus. Since the cDNA sequence of proCAP18 predicts a single methionine at residue 61, purified protein was treated with CNBr in 75% formic acid and then sequenced. Two sequences were obtained: N-DPQQLEDAKPY-C and N-PQQLEDAKPY-C. The first is identical to the predicted proCAP18 sequence starting at residue 62 and results from CNBr-mediated cleavage of proCAP18 after Met 61. The second sequence, identical to proCAP18 beginning at Pro 63, is attributable to cleavage of the acid-labile Asp-Pro bond between residues 62 and 63. Electrospray mass spectroscopy confirmed the presence of full-length proCAP18 (data not shown). Contamination of proCAP18 with CAP18p was about 0.1% by mass (Fig. 1G).

CAP18p was presumptively identified immunologically and confirmed by complete Edman sequencing.

The p15s were identified using a previously described guinea pig anti-rabbit p15 serum (35) and determined to be free of detectable CAP18p contamination by immunoblotting with goat anti-CAP18p serum (Fig. 1G) (limit of detection, ≤0.1% mass contamination).

Using the recovered purified proteins as standards, immunoblots of freshly collected and detergent-extracted rabbit peritoneal exudate PMNL revealed 32 ± 2 μg of p15 (A plus B) and 4.4 ± 1 μg of proCAP18 per 1 × 107 cells. Total recovery of the cathelicidins in purified form (i.e., p15A plus p15B and proCAP18 plus CAP18p) ranged from 35 to 60%.

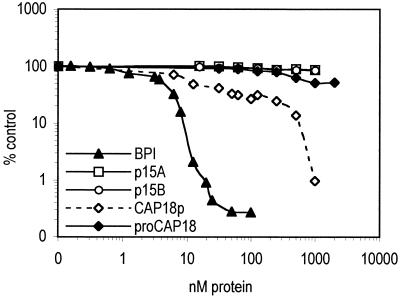

Antimicrobial activities of purified cathelicidins against E.coli K1/r in isotonic media.

Antimicrobial properties of the highly purified rabbit cathelicidins were measured by luminometry of bioluminescent E. coli K1/r as described in Materials and Methods. Results using this direct measurement of bacterial metabolism closely matched the enumeration of colonies after plating in molten agar (reference 26 and data not shown). Under the isotonic salt conditions used, neither the p15 isoforms nor proCAP18 exhibited significant independent antibacterial activity (Fig. 2). In contrast, CAP18p displayed independent cytotoxic activity (90% inhibitory concentration [IC90], ∼600 nM) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Antimicrobial activities of purified cathelicidins against E. coli K1/r in isotonic media. Independent antimicrobial activity of rabbit cathelicidins and BPI against E. coli K1/r(pCGLS1) at a concentration of 1 × 106/ml was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Points represent the means of 3 to 20 independent determinations. Bioluminescence of bacterial ATP-dependent luciferase was measured as described in the text after 2 h of incubation. The luminescence of untreated growing control bacteria is 100%, and the antimicrobial effect is the percentage of control light counts remaining after 2 h of incubation.

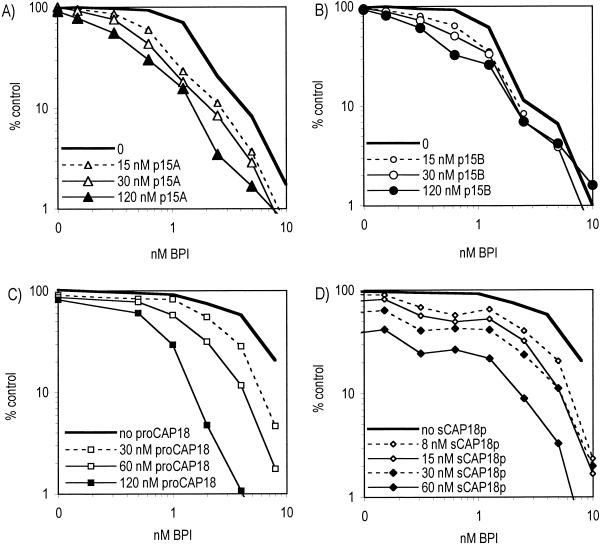

Antimicrobial synergy between individual cathelicidin species and BPI.

Antibacterial synergy between the rabbit p15s and BPI has previously been demonstrated under conditions in which the p15s alone produced no detectable antibacterial effect on E. coli (12, 18). We therefore reexamined the effects of the four cathelicidin species under the same experimental conditions described above but now in the presence of purified BPI. BPI alone expressed potent antibacterial activity (IC90, ∼10 nM) against E. coli K1/r (Fig. 2). As previously shown, p15A (and to a lesser extent p15B) decreased the amount of BPI required to achieve an antimicrobial effect (Fig. 3A and B). Remarkably, pronounced antibacterial synergy was also observed between BPI and intact proCAP18 (Fig. 3C) as well as with CAP18p (Fig. 3D). These findings demonstrate that combinations of each of the unprocessed forms of rabbit cathelicidins with BPI exhibit increased cytotoxic activity against encapsulated E. coli over that of either protein alone.

FIG. 3.

Cathelicidins synergize with BPI. E. coli K1/r(pCGLS1) was incubated alone (100%) or with dilutions of BPI in the presence of different doses of p15A (A), p15B (B), proCAP18 (C), and CAP18p (D). Data represent the means of 3 to 6 independent experiments.

Antimicrobial synergy between CAP18p and p15s.

Independent antibacterial activity of the p15s has been previously reported (12); however, reexamination of those p15 preparations revealed up to 5% contamination with CAP18p (data not shown). That amount of CAP18p alone is insufficient to kill E. coli K1/r (Fig. 2), raising the possibility that the effects previously observed reflected antibacterial synergy between the p15s and CAP18p. To test this hypothesis, we measured the killing of E. coli by combinations of low doses of CAP18p and increasing amounts of p15A or p15B. Figure 4 shows that both p15A and p15B act in antimicrobial synergy with CAP18p. Thus, the p15s can act in synergy not only with BPI but also with CAP18p.

FIG. 4.

Synergy between CAP18p and p15s. E. coli K1/r(pCGLS1) was incubated alone (100%) or with dilutions of CAP18p in the presence of increasing doses of p15A (A) and p15B (B). Data represent the means of three to six independent experiments.

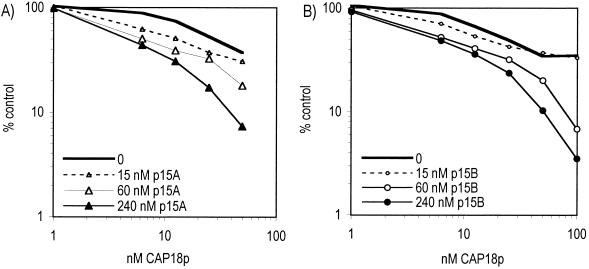

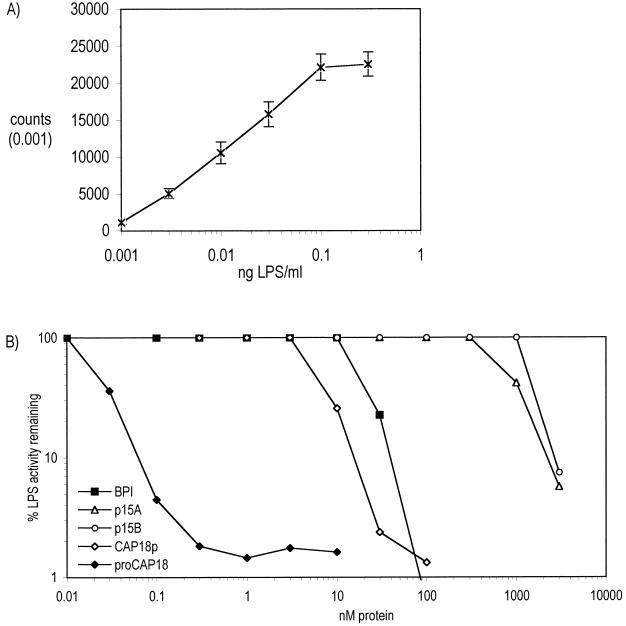

LPS-neutralizing activity of purified cathelicidins.

Both p15s and CAP18p have been shown to neutralize the endotoxic activities of LPS, a unique glycolipid of gram-negative bacteria (8, 11). We therefore examined the effects of each of the purified rabbit cathelicidins, and of BPI for comparison, on lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence of human leukocytes triggered by LPS. In the presence of LBP, LPS produced dose-dependent activation of leukocyte chemiluminescence (Fig. 5A). All four cathelicidins and BPI inhibited LPS-triggered chemiluminescence but with remarkably different potencies (Fig. 5B). Both p15 isoforms inhibited the chemiluminescent response to 0.1 ng of LPS/ml with an IC90 of ∼2 μM, whereas BPI and CAP18p had similar effects between 10 and 50 nM and proCAP18 produced similar inhibition at less than 0.1 nM. This effect of proCAP18 was apparently specific for LPS-induced cell activation and did not reflect the toxicity of proCAP18 to the leukocytes: activation of leukocytes by added synthetic bacterial lipopeptide was unaffected by proCAP18 at doses that ablated cell responses to LPS (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Inhibition of LPS by rabbit cathelicidins and BPI. (A) LPS stimulates chemiluminescence in purified primary human leukocytes in a dose-dependent fashion in the presence of 10 nM LBP and lucigenin. (B) To determine LPS-neutralizing activity, BPI (closed squares), p15A (open triangles), p15B (open circles), CAP18p (open diamonds), or proCAP18 (closed diamonds) was added to leukocyte suspensions before the addition of 0.1 ng of E. coli J5 LPS/ml. Data presented represent the means ± standard errors of the means for 10 to 20 determinations (A) or the means of 4 to 8 determinations (B).

DISCUSSION

The recognition that professional phagocytes and other animal and plant cells produce and store polypeptides that exhibit antimicrobial properties in vitro has stimulated the search for endogenous antibiotics with therapeutic potential (2, 9). Such studies relied initially upon biochemical purification to characterize these agents. In the case of cathelicidins, molecular cloning strategies have been devised based on the highly conserved N-terminal cathelin-like domain (25). Sequences corresponding to the predicted C-terminal peptides have served as templates for peptide synthesis, and the resulting molecules have then been functionally characterized (26).

Few studies have assessed the relative potencies of cathelicidins isolated from the granulocytes of a single mammalian species. To address this issue, we aimed at comparing the bioactivities of the previously identified cathelicidins of rabbit granulocytes alone and in various combinations. However, since previous studies have shown potent synergy among antimicrobial polypeptides (12, 18), it was imperative to demonstrate that each purified protein was essentially free of contamination by any of the others. According to chromatographic, immunological, and bioassay criteria, virtually pure proCAP18, CAP18p, p15A, p15B, and BPI were obtained by using the methods described here, allowing a meaningful comparison of their activities in our assays. Of the four cathelicidin polypeptides, only CAP18p showed independent antibacterial activity against encapsulated E. coli in buffered isotonic medium but at a level at least 50-fold less than that of BPI. However, under the same conditions, all four cathelicidin species, including the proform of CAP18, acted in synergy with BPI concentrations that alone were less able to kill the target bacteria.

BPI exhibits antimicrobial synergy with a variety of host-derived and exogenous compounds, including defensins (11), phospholipase A2 (3), complement (30), and antibiotics (13). In addition, BPI and p15s accumulate in extracellular inflammatory fluids elicited in rabbits by intraperitoneal injection of sterile glycogen (29). At the concentrations found in vivo, these agents show synergy in vitro (29). Synergy between BPI and p15s has also been described in whole human blood (11). These observations provide further evidence of the importance of amplification of antimicrobial host defenses by synergism between many antimicrobial agents present within phagocytes as well as extracellularly after their release.

The revelation that previous preparations of p15s were contaminated with up to 5% CAP18p necessitated a better definition of the participation of each of the individual polypeptides tested. We show here that in the absence of detectable CAP18p contamination (<0.1% by mass), combinations of p15s and BPI exhibit antimicrobial synergy against E. coli K1/r, although less dramatically than when small amounts of CAP18p are also present. Our data also reveal for the first time synergy among cathelicidin family members, suggesting different mechanisms of action within this family of proteins. The potent synergy between the p15s and CAP18p (Fig. 4) most likely explains the variably observed independent antimicrobial activities of the p15s reported previously (12, 18).

All proteins tested were able to inhibit LPS-induced chemiluminescence in human leukocytes, although with different relative potencies compared to their independent antimicrobial activities. Both BPI and CAP18p were active in the nanomolar range, as previously reported (7, 11, 15). The p15s were least active (IC90, ∼2 μM). Remarkably, the unprocessed proCAP18 was orders of magnitude more potent on a molar basis than its C-terminal peptide and even BPI. Our findings contrast with an earlier report that observed an endotoxin-neutralizing activity of proCAP18 less than or equal to that of CAP18p (7). It should be noted, however, that the preparations of proCAP18 that were equipotent with CAP18p in those studies were significantly contaminated with CAP18p, as evidenced by Edman degradation and N-terminal sequence analysis (7), precluding, until now, unambiguous functional characterization of proCAP18.

Thus, in contrast to the prevailing view that cathelicidins require proteolytic processing for expression of their biological activities, unprocessed rabbit cathelicidins, notably proCAP18, can exert potent LPS-inhibitory activity and act in concert with BPI and other host defense molecules (K. A. Zarember et al., unpublished data) to contribute to antimicrobial host defenses. In this respect, the cathelicidins differ from the defensins, which apparently require full processing and release of the mature C-terminal peptide for the expression of biological activity (6, 27). The structural basis of the expression of the bioactivities of the unprocessed cathelicidins is not yet known. Of note, whereas the various prodefensins have little or no net charge (16), rabbit cathelicidins are highly cationic at a physiologic pH (proCAP18, 8+ p15, 11+; CAP18p, +11). Thus, if net cationicity is a major determinant of interactions with anionic bacterial surface molecules such as LPS and, hence, of antimicrobial activity, it is not surprising that cationic unprocessed cathelicidins, but not the neutral prodefensins, interact with these bacterial targets. The remarkable potency of proCAP18 in neutralizing endotoxin suggests that structural determinants within the conserved N-terminal cathelin-like domain also contribute to host defense either by mediating interactions with microbial targets or with host systems. The cathelin-like domain may also play a role in other biological activities of cathelicidin proforms that are not exhibited by the C-terminal peptides, including the monocyte chemoattractant activity of proBac5 and the cysteine protease inhibitory activity of proBac7 (28). The isolation and characterization of the highly conserved cathelin-like domain from different cathelicidins and a reanalysis of cathelin itself should be major targets for future studies.

Our findings lend further credence to the belief that the extracellular accumulation of unprocessed cathelicidins is functionally significant (14, 19, 22, 29, 35). Unlike the defensins, which are fully processed before storage in and release from cytoplasmic granules (27), the cathelicidins are stored in the unprocessed form and in granules that are more readily mobilized, permitting substantial extracellular accumulation of unprocessed species (23, 32-35). The potent endotoxin-neutralizing activity of proCAP18 is of particular interest as the human homologue (hCAP18) is natively associated with plasma lipoproteins (24), where it could facilitate lipoprotein-dependent neutralization and clearance of endotoxin. Although the p15s appear to be less potent, their abundance may confer a substantial role in antimicrobial cytotoxicity, especially after the processing of proCAP18 to CAP18p.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (R37DK05472 and AI18571) and funding from Xoma, Ltd. K.A.Z. was supported in part by NIH training grant T32AI07180.

We are grateful to Yvette Weinrauch and Ofer Levy for helpful discussions and to Elena Rus and Brian Morrison of the Protein Structural Facility at the University of Iowa for sequence and compositional analysis as well as the synthesis of CAP18p.

Editor: R. N. Moore

REFERENCES

- 1.Cross, A. S., P. Gemski, J. C. Sadoff, F. Orskov, and I. Orskov. 1984. The importance of the K1 capsule in invasive infections caused by Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Dis. 149:184-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elsbach, P. 1990. Antibiotics from within: antibacterials from human and animal sources. Trends Biotechnol. 8:26-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elsbach, P., J. Weiss, R. C. Franson, S. Beckerdite-Quagliata, A. Schneider, and L. Harris. 1979. Separation and purification of a potent bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein and a closely associated phospholipase A2 from rabbit polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Observations on their relationship. J. Biol. Chem. 254:11000-11009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elsbach, P., J. Weiss, and O. Levy. 1999. Oxygen-independent antimicrobial systems of phagocytes, p. 801-817. In J. I. Gallin and R. Snyderman (ed.), Inflammation: basic principles and clinical correlates, 3rd ed. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 5.Frackman, S., M. Anhalt, and K. H. Nealson. 1990. Cloning, organization, and expression of the bioluminescence genes of Xenorhabdus luminescens. J. Bacteriol. 172:5767-5773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganz, T., L. Liu, E. V. Valore, and A. Oren. 1993. Posttranslational processing and targeting of transgenic human defensin in murine granulocyte, macrophage, fibroblast, and pituitary adenoma cell lines. Blood 82:641-650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirata, M., Y. Shimomura, M. Yoshida, J. G. Morgan, I. Palings, D. Wilson, M. H. Yen, S. C. Wright, and J. W. Larrick. 1994. Characterization of a rabbit cationic protein (CAP18) with lipopolysaccharide-inhibitory activity. Infect. Immun. 62:1421-1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirata, M., Y. Shimomura, M. Yoshida, S. C. Wright, and J. W. Larrick. 1994. Endotoxin-binding synthetic peptides with endotoxin-neutralizing, antibacterial and anticoagulant activities. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 388:147-159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiss, P. H., and H. Zinnser. 1908. Experimental and clinical studies on the curative action of leucocyte extracts in infections. J. Med. Res. 19:323-469. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larrick, J. W., J. G. Morgan, I. Palings, M. Hirata, and M. H. Yen. 1991. Complementary DNA sequence of rabbit CAP18—a unique lipopolysaccharide binding protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 179:170-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levy, O., C. E. Ooi, P. Elsbach, M. E. Doerfler, R. I. Lehrer, and J. Weiss. 1995. Antibacterial proteins of granulocytes differ in interaction with endotoxin. Comparison of bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein, p15s, and defensins. J. Immunol. 154:5403-5410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levy, O., C. E. Ooi, J. Weiss, R. I. Lehrer, and P. Elsbach. 1994. Individual and synergistic effects of rabbit granulocyte proteins on Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Investig. 94:672-682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin, Y., W. J. Leach, and W. S. Ammons. 1996. Synergistic effect of a recombinant N-terminal fragment of bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein and cefamandole in treatment of rabbit gram-negative sepsis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:65-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malm, J., O. Sørensen, T. Persson, M. Frohm-Nilsson, B. Johansson, A. Bjartell, H. Lilja, M. Ståhle-Bäckdahl, N. Borregaard, and A. Egesten. 2000. The human cationic antimicrobial protein (hCAP-18) is expressed in the epithelium of human epididymis, is present in seminal plasma at high concentrations, and is attached to spermatozoa. Infect. Immun. 68:4297-4302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marra, M. N., C. G. Wilde, M. S. Collins, J. L. Snable, M. B. Thornton, and R. W. Scott. 1992. The role of bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein as a natural inhibitor of bacterial endotoxin. J. Immunol. 148:532-537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michaelson, D., J. Rayner, M. Couto, and T. Ganz. 1992. Cationic defensins arise from charge-neutralized propeptides: a mechanism for avoiding leukocyte autocytotoxicity? J. Leukoc. Biol. 51:634-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okrent, D. G., A. K. Lichtenstein, and T. Ganz. 1990. Direct cytotoxicity of polymorphonuclear leukocyte granule proteins to human lung-derived cells and endothelial cells. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 141:179-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ooi, C. E., J. Weiss, O. Levy, and P. Elsbach. 1990. Isolation of two isoforms of a novel 15-kDa protein from rabbit polymorphonuclear leukocytes that modulate the antibacterial actions of other leukocyte proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 265:15956-15962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panyutich, A., J. Shi, P. L. Boutz, C. Zhao, and T. Ganz. 1997. Porcine polymorphonuclear leukocytes generate extracellular microbicidal activity by elastase-mediated activation of secreted proprotegrins. Infect. Immun. 65:978-985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radermacher, S. W., V. M. Schoop, and H. J. Schluesener. 1993. Bactenecin, a leukocytic antimicrobial peptide, is cytotoxic to neuronal and glial cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 36:657-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scocchi, M., B. Skerlavaj, D. Romeo, and R. Gennaro. 1992. Proteolytic cleavage by neutrophil elastase converts inactive storage proforms to antibacterial bactenecins. Eur J. Biochem. 209:589-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi, J., and T. Ganz. 1998. The role of protegrins and other elastase-activated polypeptides in the bactericidal properties of porcine inflammatory fluids. Infect. Immun. 66:3611-3617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sorensen, O., K. Arnljots, J. B. Cowland, D. F. Bainton, and N. Borregaard. 1997. The human antibacterial cathelicidin, hCAP-18, is synthesized in myelocytes and metamyelocytes and localized to specific granules in neutrophils. Blood 90:2796-2803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sorensen, O., T. Bratt, A. H. Johnsen, M. T. Madsen, and N. Borregaard. 1999. The human antibacterial cathelicidin, hCAP-18, is bound to lipoproteins in plasma. J. Biol. Chem. 274:22445-22451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tossi, A., M. Scocchi, M. Zanetti, R. Gennaro, P. Storici, and D. Romeo. 1997. An approach combining rapid cDNA amplification and chemical synthesis for the identification of novel, cathelicidin-derived, antimicrobial peptides. Methods Mol. Biol. 78:133-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Travis, S. M., N. N. Anderson, W. R. Forsyth, C. Espiritu, B. D. Conway, E. P. Greenberg, P. B. McCray, Jr., R. I. Lehrer, M. J. Welsh, and B. F. Tack. 2000. Bactericidal activity of mammalian cathelicidin-derived peptides. Infect. Immun. 68:2748-2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valore, E. V., and T. Ganz. 1992. Posttranslational processing of defensins in immature human myeloid cells. Blood 79:1538-1544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verbanac, D., M. Zanetti, and D. Romeo. 1993. Chemotactic and protease-inhibiting activities of antibiotic peptide precursors. FEBS Lett. 317:255-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinrauch, Y., A. Foreman, C. Shu, K. Zarember, O. Levy, P. Elsbach, and J. Weiss. 1995. Extracellular accumulation of potently microbicidal bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein and p15s in an evolving sterile rabbit peritoneal inflammatory exudate. J. Clin. Investig. 95:1916-1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiss, J. 1997. Assay of antibacterial activities of the bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein in natural biological fluids. Methods Mol. Biol. 78:217-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss, J. 1994. Purification and assay of bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein. Methods Enzymol. 236:173-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yomogida, S., I. Nagaoka, and T. Yamashita. 1997. Comparative studies on the extracellular release and biological activity of guinea pig neutrophil cationic antibacterial polypeptide of 11 kDa (CAP11) and defensins. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 116:99-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zanetti, M., L. Litteri, R. Gennaro, H. Horstmann, and D. Romeo. 1990. Bactenecins, defense polypeptides of bovine neutrophils, are generated from precursor molecules stored in the large granules. J. Cell Biol. 111:1363-1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zanetti, M., L. Litteri, G. Griffiths, R. Gennaro, and D. Romeo. 1991. Stimulus-induced maturation of probactenecins, precursors of neutrophil antimicrobial polypeptides. J. Immunol. 146:4295-4300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zarember, K., P. Elsbach, K. Shin-Kim, and J. Weiss. 1997. p15s (15-kDa antimicrobial proteins) are stored in the secondary granules of rabbit granulocytes: implications for antibacterial synergy with the bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein in inflammatory fluids. Blood 89:672-679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]