Abstract

Background

The etiology of maxillofacial injuries varies from one country to another and even within the same country depending on the prevailing socioeconomic, cultural and environmental factors. Periodic verification of the etiology of maxillofacial injuries helps to recommend ways in which maxillofacial injuries can be averted. The aim of the present study is therefore to analyse the characteristics and trends of maxillofacial injuries in Nigeria based on a systematic review of the literature.

Methods

A literature search using MEDLINE was conducted for publications on maxillofacial injuries in Nigeria. The relevant references in these publications were manually searched for additional non-Medline articles or abstracts. Forty-two studies met the inclusion criteria and the full-texts of these articles were thoroughly examined. Due to lack of uniformity and consistency in assessment and measurement variables, and treatment modalities in most of the studies, it was impossible to apply the traditional methods of a systematic review. Therefore, a narrative approach was conducted to report the findings of the included studies.

Results

Although, other causes like assaults, sport injuries, and industrial accidents increased in numbers, throughout the period between 1965 and 2003, road traffic crashes remained the major etiological factor of maxillofacial injuries in all regions, except northeastern region where assault was the major cause. A significant increase in motorcycles related maxillofacial injuries was observed in most urban and suburban centres of the country. Animal attacks were not an unusual cause of maxillofacial injuries in most parts of northern Nigeria. Patients in the age group of 21–30 years were mostly involved. A strong tendency toward an equal male-to-female ratio was observed between earlier and later periods.

Conclusion

Road traffic crashes remain the major cause of maxillofacial injuries in Nigeria, unlike in most developed countries where assaults/interpersonal violence has replaced road traffic crashes as the major cause of the injuries. There is a need to reinforce legislation aimed to prevent road traffic crashes and the total enforcement of existing laws to reduce maxillofacial injuries among children and adults. Special attention should also be paid by the authority to improve the socioeconomic conditions of Nigerian populace.

Background

Skeletal and soft tissue injuries of the face constitute quite a significant portion of the workload of the oral and maxillofacial surgeons in Nigeria [1]. Being the most exposed part of the body, the face is particularly vulnerable to such injuries, 20–60% of all those involved in automobile accidents having some level of facial fractures [2,3]. Surveys of facial injuries have shown that the etiology varies from one country to another and even within the same country depending on the prevailing socioeconomic, cultural and environmental factors [4-6]. Earlier studies from Europe and America revealed that road traffic crashes (RTC) were the most frequent cause of facial injuries [7,8]. However, more recent studies have shown that assault is now the most common cause of maxillofacial injuries in developed countries [9-11], whereas traffic accidents remain the most frequent cause in many developing countries [12-19].

Periodic verification of the etiology of maxillofacial injuries helps to assess the proficiency of road safety measures such as speed limit, drunk driving, and seat beat belt laws and the behavioural patterns of the people in different countries and helps to recommend other ways in which injuries to the face can be averted [20].

The aim of the present study is therefore to analyse the characteristics and trends of maxillofacial injuries in Nigeria based on a systematic review of the literature.

Methods

A computerized literature search using MEDLINE was conducted for publications on maxillofacial injuries in Nigeria published between 1970 and 2005. For this search, the medical subject headings "maxillofacial injuries" or "maxillofacial fractures" or "mandible fractures" or "middle-third fractures" or "facial fractures" or "zygoma fractures" were combined with "Nigeria" or "Africa". The Boolean operator 'AND' was used to combine and narrow the searches. We manually searched the references in these articles to look for additional relevant non-Medline articles or abstracts. The full-texts of all these articles were thoroughly examined. Personal contacts were also made with institutions and investigators of previous studies for missing data and also for the provision of articles found suitable for the review, but not readily available to us. One author (WLA) conducted the literature search. All the authors agreed upon inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

1. Availability of the full-text article

2. Retrospective or prospective studies

3. All age groups (Children and adults)

4. Civilian-type injuries

Publications on maxillofacial injuries sustained during Nigerian civil war were excluded from the review.

Assessment of the studies

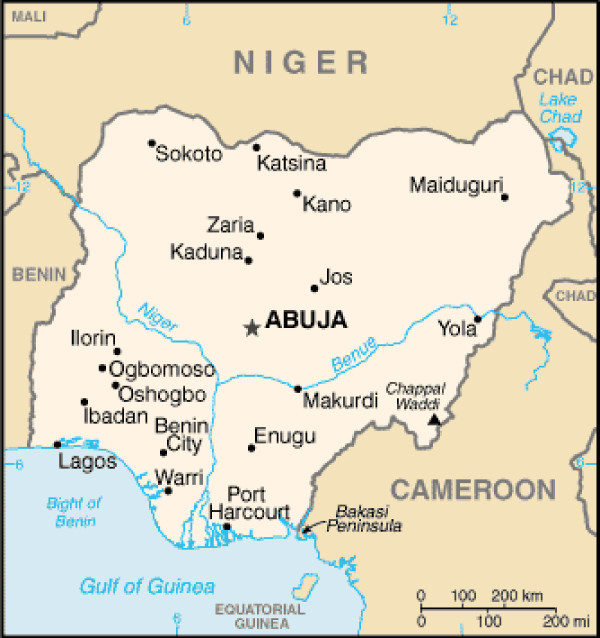

A total of 44 full-text articles and abstracts were identified. Two articles on maxillofacial injuries sustained during the Nigerian civil war were excluded. A total of 42 publications published between January 1977 and April 2005, which satisfied the inclusion criteria were, therefore included in the review. These included 34 Medline and 8 non-Medline articles. These publications were based on patients seen and treated between 1965 and 2003 from different centers of the six geopolitical zones of the country (Figure 1) including: Ibadan, south west (SW) [18,19,21-35], Lagos (SW) [36-40], Ife (SW) [1,41-46], Kaduna, north central (NC) [47-50], Sokoto, north west (NW) [51,52], Maiduguri, north east (NE) [4,53,54], Enugu, south east (SE) [15,16,55], and Benin city, south south (SS) [56] (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Map of Nigeria (source: CIA's The World Factbook). Ife (not shown) lies in the north east of Ibadan below Oshogbo.

Table 1.

Location of investigations, aetiology of injury and gender distribution.

| Author (Ref.-No.) | Locationa | Major cause of injury | 2nd major cause of injury | % motorcycle related | Male/female ratio (%) | Tissue affected |

| Ajagbe et al. (21) | Ibadan (SW) | RTC (63) | Falls (19) | 10 | 2.1:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Nwoku et al. (36) | Lagos (SW) | RTC | ## | ### | 3:1 | Hard/Soft Tissues |

| Ajagbe et al. (34) | Ibadan (SW) | RTC | Falls | 15.7 | 3:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Adekeye (47) | Kaduna (NC) | RTC (76) | Assaults (13) | 22 | 16.9:1 | Hard/Soft Tissues |

| Adekeye (48) | Kaduna (NC) | RTC (82) | Falls | ### | 24:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Adekeye (49) | Kaduna (NC) | RTC | ## | ### | 2:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Nyako (23) | Ibadan (SW) | RTC (77) | Assaults (9) | 10.6 | 6.4:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Odusanya (41) | Ife (SW) | RTC (53) | Falls | 22.1 | 5.4:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Abiose (22) | Ibadan (SW) | RTC (81) | Assaults (9) | ### | 5.5:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Akinwande (37) | Lagos (SW) | RTC (65) | Assaults (12) | 18.5 | 4.2:1 | Hard/Soft Tissues |

| Abiose (32) | Ibadan (SW) | RTC (81) | Assaults (7) | ### | 14:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Arotiba (38) | Lagos (SW) | RTC (100) | # | 6.3 | 2.3:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Arotiba (39) | Lagos (SW) | RTC (63) | Assaults (20) | 4 | 2.1:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Oji (15) | Enugu (SE) | RTC (83) | Assaults (8) | 21 | 3:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Ogunbodede (52) | Sokoto (NW) | bCamel bite | # | # | # | Hard/Soft Tissues |

| Denloye et al. (33) | Ibadan (SW) | RTC (47) | Falls (41) | ### | 1.8:1 | Hard/Soft Tissues |

| Ugboko et al. (1) | Ife (SW) | RTC (72) | Falls (11) | 14.5 | 4.1:1 | Hard/Soft Tissues |

| Akinwande et al. (40) | Lagos (SW) | bGunshots (100) | # | # | 5.1:1 | Hard/Soft Tissues |

| Oji (55) | Enugu (SE) | RTC (28) | Assaults (25) | 5 | 2.6:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Ugboko et al. (46) | Ife (SW) | RTC (50) | Falls (31) | 1.9 | 6.4:1 | Hard/Soft Tissues |

| Oji (16) | Enugu (SE) | RTC (83) | Assaults (8) | 21 | 3:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Olasoji (53) | Maiduguri (NE) | bAssaults (100) | # | # | 2.5:1 | Hard/Soft Tissues |

| Ugboko et al. (42) | Ife (SW) | bGunshots (100) | # | # | 21:1 | Hard /Soft Tissues |

| Fasola et al. (28) | Ibadan (SW) | bSports (100) | # | # | 4.1:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Fasola et al. (30) | Ibadan (SW) | RTC (38) | Falls (25) | ### | 2.6:1 | Soft Tissue |

| Fasola et al. (19) | Ibadan (SW) | RTC (79) | Assaults (9) | ### | 7.6:1 | Hard/Soft Tissues |

| Fasola et al. (25) | Ibadan (SW) | RTC (52) | Falls (24) | 3.2 | 2.6:1 | Hard/Soft Tissues |

| Fasola et al. (26) | Ibadan (SW) | RTC (53) | Falls (24) | ### | 2.8:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Olasoji et al. (4) | Maiduguri (NE) | Assaults (48) | RTC (36) | 9 | 2.2:1 | Hard /Soft Tissues |

| Olasoji et al. (54) | Maiduguri (NE) | RTC (54) | Falls (25) | 2 | 7.5:1 | Hard/Soft Tissues |

| Ugboko et al. (51) | North (NE, NW, NC) | bAnimal attacks | # | # | 4:1 | Hard/Soft Tissues |

| Oginni et al. (43) | Ife (SW) | bDog bites | # | # | 5:3 | Soft Tissue |

| Oginni et al. (44) | Ife (SW) | Falls (38) | RTC (33) | # | 1.4:1 | Soft Tissue |

| Fasola et al. (29) | Ibadan (SW) | RTC (76) | Assaults (9) | ### | 2.7:1 | Hard/Soft Tissues |

| Fasola et al. (31) | Ibadan (SW) | RTC (82) | Sports (8) | ### | 5.3:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Fasola et al. (18) | Ibadan (SW) | RTC (69) | Assaults (12) | 20.6 | 3.3:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Fasola et al. (24) | Ibadan (SW) | RTC (69) | # | 15.1 | 2.9:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Fasola et al. (27) | Ibadan (SW) | RTC (59) | Falls (21) | 1.9 | 1:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Saheeb et al. (56) | Benin (SS) | RTC (66) | Assaults (10) | 26.5 | 2.7:1 | Hard /Soft Tissues |

| Adebayo et al. (50) | Kaduna (NC) | RTC (56) | Falls (24) | ### | 4.7:1 | Hard Tissue |

| Bankole et al. (35) | Ibadan (SW) | Falls (66) | RTC (18) | ### | 2.3:1 | Soft Tissue |

| Ugboko et al. (45) | Ife (SW) | RTC (74) | Falls/Assaults (14) | 9.4 | 6:1 | Hard Tissue |

a(SW) South-west, (SE) South-east (SS) South-south, (NW) North-west, (NE) North-east, (NC) North-central

bPublications on a single specific etiology

RTC = road traffic crash

# = not applicable

## = not specified

### = not separately classified

A protocol was prepared to identify the following features of each study: type of participants (i.e. adults or children or both groups), number of injuries analyzed, etiology of injury, peak age of incidence, gender predilection, site of injury, target population, as well as period and location of the study (Table 1, 2). Treatment modalities were also assessed.

Table 2.

Type of included study, number of patients analyzed, target population and peak age of incidence.

| Author (Ref.-No.) | Type of study | n of patients | Target population | Bone mostly affected (%) | Peak age of incidence, years (%) |

| Ajagbe et al (21) | retrospective | 203 | total | mandible (60.5) | 21–30 (32) |

| Nwoku et al (36) | retrospective | 84 | total | mandible (90) | ## |

| Ajagbe et al (34) | retrospective | 324 | total | mandible (60) | 21–30 |

| Adekeye (47) | prospective | 1447 | total | mandible (62.5) | 21–30 (56) |

| Adekeye (48) | retrospective | 337 | total | # | 21–40 (80) |

| Adekeye (49) | retrospective | 85 | Children | mandible | >10 |

| Nyako (23) | retrospective | 341 | total | mandible (73) | 21–30 (46) |

| Odusanya (41) | retrospective | 231 | total | mandible (67) | 21–30 |

| Abiose (22) | retrospective | 104 | total | mandible (75) | 21–30 (43) |

| Akinwande (37) | prospective | 208 | total | mandible | 21–30 (51) |

| Abiose (32) | retrospective | 59 | total | # | 21–30 |

| Arotiba (38) | prospective | 128 | total | mandible (62) | 20–29 (>40) |

| Arotiba (39) | prospective | 202 | total | mandible (64) | 20–29 (40) |

| Oji (15) | retrospective | 900 | total | mandible (42) | 21–30 (36) |

| Ogunbodede (52) | case report | 1 | # | # | # |

| Denloye et al (33) | retrospective | 106 | Children | mandible | 0–8 (62) |

| Ugboko et al (1) | retrospective | 442 | total | mandible (64) | 21–30 (39) |

| Akinwande et al (40) | prospective | 35 | total | mandible | 20–34 (66) |

| Oji (55) | retrospective | 40 | Children | mandible (89) | 9–11 (40) |

| Ugboko et al (46) | retrospective | 52 | Children | mandible (62) | 12–14 (50) |

| Oji (16) | retrospective | 900 | total | mandible (53) | 21–30 (36) |

| Olasoji (53) | retrospective | 105 | total | mandible (43) | 20–29 (42) |

| Ugboko et al (42) | retrospective | 22 | total | Zygoma (27) | 21–40 |

| Fasola et al (28) | retrospective | 77 | total | mandible (54.4) | 21–30 (52) |

| Fasola et al (30) | retrospective | 831 | total | # | 21–30 (33) |

| Fasola et al (19) | prospective | 103 | total | # | 21–30 (47) |

| Fasola et al (25) | retrospective | 93 | children | mandible (86) | 11–16 (54) |

| Fasola et al (26) | retrospective | 72 | children | # | 12–16 (57) |

| Olasoji et al (4) | prospective | 306 | total | mandible (66) | 21–30 (41) |

| Olasoji et al (54) | retrospective | 102 | Children | mandible (73) | 12–15 (54) |

| Ugboko et al (51) | retrospective | 34 | total | mandible (56) | 11–30 (74) |

| Oginni et al (43) | retrospective | 8 | children | # | ## |

| Oginni et al (44) | retrospective | 174 | children | # | ## |

| Fasola et al (29) | aretrospective | 531 | total | # | 21–30 (39) |

| Fasola et al (31) | prospective | 76 | total | # | 21–30 (51) |

| Fasola et al (18) | bpro/retrospective | 824 | total | mandible (75) | 21–30 (36) |

| Fasola et al (24) | prospective | 159 | total | mandible | 21–30 (36) |

| Fasola et al (27) | retrospective | 53 | adults | mandible (96) | 60–70 (77) |

| Saheeb et al (56) | retrospective | 250 | total | mandible (65) | 20–30 (32) |

| Adebayo et al (50) | retrospective | 443 | total | mandible (64) | 20–39 (65) |

| Bankole et al (35) | retrospective | 64 | children | # | 0–5 |

| Ugboko et al (45) | retrospective | 128 | total | # | 21–30 (38) |

a analysis of concomitant injuries in patients with maxillofacial fractures

bcomparative study

total = all age groups

# = not applicable

## = not specified

Most of the studies lack uniformity and consistency in assessment and measurement variables (information bias) and treatment modalities. The age bracket of patients considered as "children" by several investigators varied considerably (Fasola et al [26], 16 years and below; Oji [55], under 11 years; Olasoji, under 15 years; Ugboko et al, 14 years and below [46]; Denloye et al [33], less than 17 years; Oginni et al [44], 15 years and below). Repetition of the same data in different studies was also observed. While most of the published articles focused only on hard tissue injuries, few others reported on either hard and soft tissue injuries or soft tissue only (Table 1). Although, the majority of the patients in the studies were treated by closed reduction and fixation methods, uniformity in treatment was lacking. Due to the heterogeneity of the study methodologies in this review it was not possible to apply the traditional methods of a systematic review. A meta-analysis is only suitable if there is sufficient similarity in the populations studied and the measurements used. This was not the case with the studies identified in this review. Therefore, a narrative approach was taken to report the findings of the included studies.

Data was analysed using the SPSS for window (version 11.5; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) statistical software package. Descriptive statistics and the non-parametric chi square test were used to analyse the incidence of injuries in different time periods. The critical level of significance was set at p < .05.

Results

Of the 42 articles reviewed, 31 were retrospective studies, 9 prospective, 1 article was a case report and 1 article was a comparative study of a prospective and a retrospective data. Road traffic crash (RTC) was the major cause of maxillofacial injuries in both children and adults in all the zones of the country with the exception of north eastern states where assault was the major cause of injuries (Table 1). Although, motor vehicles were responsible for most cases of RTC, motorcycle related injuries increased significantly between 1965 and 2003. Between 1965 and 1999 in Ibadan, the number of motorcycle-related maxillofacial injuries increased by a factor of 2.6, and more significant cases (p = .02) of motorcycle related injuries were recorded in 1978–1982 period compared to 1995–1999 (Table 3). In Enugu (SE) Nigeria, between 1985 and 1995, the number of motorcycle related maxillofacial injuries increased by a factor of 1.6 (Table 3). An increase in the number of motorcycle related maxillofacial injuries was also observed between 1973 and 2000, and between 1976 and 1995 in Kaduna (NC) [48,51] and Ife (SW) [1,41] respectively. In Benin (SS) [56] and Lagos (SW) [37], 26.5% and 19.0% of cases with maxillofacial injuries were involved in motorcycle related crashes respectively, and motorcycle passengers sustained more severe injuries than other vehicle users [37,56].

Table 3.

Analysis of road traffic injuries due to motor vehicles and motorcycles between 1965 and 1999 in Ibadana and between 1985 and 1995 in Enugub.

| IBADAN (South-west, Nigeria) | ||||

| Types of automobile involved | Study period | |||

| 1965–1975 | 1978–1982 | 1982–1984 | 1995–1999 | |

| Motor vehicles | 46.3% | 84.9% | 80% | 63.4% |

| Motorcycles | 7.8% | 10.6% | # | 20.6%* |

| ENUGU (South-east, Nigeria) | ||||

| Study period | ||||

| 1985–1990 | 1991–1995 | |||

| Motor vehicles | 59% | 59% | ||

| Motorcycles | 16% | 25% | ||

a adapted from Abiose [22], Ajagbe et al [21], Fasola et al [18] and Nyako [23]

b adapted from Oji [16]

# = not specified

* statistically significant (p = 0.02)

Pedestrian related maxillofacial fractures also increased in major cities across the country. In Ibadan (SW), an increase by a factor of 3.2 was reported between 1978 and 1999 [18,23] and in Lagos (SW), 35.6% (1983–1986) and 28.1% (1989–1992) of patients involved in RTC were pedestrians hit by vehicles [37,38].

Assaults were the second most common cause of injuries in most centres followed by falls (Table 1). Falls were important causes of injuries in children. Increase in the number of patients who sustained injuries as a result of assaults, falls, sports injuries and industrial accidents was observed in most centers over the years [1,18,35,37,46,48,51,53]. Animal attacks were also a frequent cause of maxillofacial injuries especially in northern part of the country [4,43,45,52].

The peak age of incidence of maxillofacial injuries was 21–30 years in most centers followed by 31–40 years. In children, injuries occurred mostly in children aged > 10 years. More males were affected than females in all age groups. A tendency towards an equal male-to-female ratio was observed between earlier and later studies in most urban centers. A significant reduction in male-to-female ratio from 16.9:1 (1973–1978) to 3:1 (1991–2000) was reported from Kaduna (NC) (Table 1). Another significant reduction in male-to-female ratio from 6.4:1 (1978–1982) to 3.3:1 (1995–1999) was reported from Ibadan (SW) (Table 1).

The Mandible was the most frequently involved bone in maxillofacial fractures in all the centers across the country, and the most frequently involved middle-third bone was the zygoma [1,18,22,32,50]. The LeFort I fracture was the most common of the LeFort fracture types [1,4,22]. Analysis of fracture of the mandible revealed mandibular body as the most frequently involved part, followed by symphyseal/ parasymphyseal region [1,4,18,23,25,37-39,46,47,50]. Dentoalveolar and condylar fractures were less frequently reported. Another remarkable feature of maxillofacial injuries in most reports was extensive soft tissue injuries [30,18,37,38,56].

Closed reduction and dental wiring with arch bars, direct wires and eyelet wires combine with intermaxillary fixation were the most common form of treatment [1,21,34,47,50] for mandibular fractures. Wire osteosynthesis is employed for open reduction and internal fixation of mandibular fractures in few cases [1,21,22,50]. Fractures of the maxillae/LeFort fractures were reduced and fixed by eyelets/arch bars combined with suspension wires and intermaxillary fixation [1,32,34,47,50]. Zygomatic complex fractures were treated either conservatively or by either closed or open reduction with Gillies' temporal approach, lateral coronoid approach or transosseous wiring [21,42,45,47].

Discussion

The large variations in assessment and measurement variables, as well repetition of data employed by previous investigators of maxillofacial injuries in Nigeria made a systematic review impossible. However, analysis of the previous studies on maxillofacial injuries in Nigeria showed a noticeable trend and characteristic.

Although, road traffic crashes remained the major etiological factor of maxillofacial injuries other causes like assaults, sport injuries and industrial accidents have increased in numbers between 1965 and 2003 in Nigeria. This finding is in agreement with reports from other developing countries where RTC remains the major etiologic factor of maxillofacial injuries [12,13,17], but contrasts reports from developed countries where assaults and interpersonal violence has replaced RTC as the major cause of maxillofacial injuries [6,10,11,18]. Civilian-type maxillofacial injuries were rare prior to Nigerian independence in 1960 [21]. Immediate post independence period witnessed a significant increase in the numbers of motor vehicles imported into the country. It is worthwhile to note that the period from 1965 up to the present time has witnessed a steady increase in the number of second-hand vehicles into Nigeria. Also, lack of enforcement of reshipment inspection rules and regulations has encouraged the importation of vehicles whose road worthiness leaves much to be desired [1]. In addition, the roads are badly maintained, and there is general lack of enforcement of traffic rules and regulations, especially the use of seat belts. Non-usage of protective elements was also thought to be responsible for extensive soft tissue injuries seen in maxillofacial injured patients [18,37,38,56].

Over the last 40 years, there has been a significant increase in the number of maxillofacial injuries that resulted from motorcycle accidents in Nigeria (Table 3). These findings contrast that of others [57] who reported a decrease in the number of motorcyclists involved in maxillofacial injuries. However, Konto et al [58] reported that bicycle related maxillofacial fractures increased by 19.3% between 1981 and 1997 in Finland. The increase in the present study is due to a significant increase in the number of motorcycles plying Nigeria roads. Even in Abuja, the nation's capital, anecdotal evidence has shown that motorcyclists and their passengers are involved in more than 55% of cases of road traffic crashes. In the United States of America (USA), the number of registered motorcycles increased from 600,000 units in 1961 to 3.3 million units in 1971; a 450% increase within a decade [59,60]. This pattern was also recognised in Nigeria when the number increased from 144,480 units to 284,124 units between 1976 and 1981, an increase of almost 200% within 5 years [61]. Motorcycles have become a prominent mode of transportation in both urban and suburban cities in Nigeria. Frequent traffic jams as a result of poor road network in the country have made motorcycles attractive to commuters because motorcycles can pass through narrow ways [18]. However, most of the motorcyclists are unlicensed and often do not follow traffic rules and regulation. Fasola et al [24] reported that only one (3.8%) of the motorcyclists who sustained maxillofacial injuries within Ibadan city (SW) wore a crash helmet while Saheeb and Etetafia [56] reported that none of the motorcyclists and their passengers involved in RTC in Benin city (SS) wore protective helmet.

The number of pedestrians involved in maxillofacial injuries has also been on the increase especially in urban centres unlike reported elsewhere [57]. This is peculiar to the overpopulated cities with few subways and overhead bridges. Therefore, it is relatively common for pedestrians to have to run in oncoming vehicular traffic [18,38]. Konto et al [58] also reported an increase in pedestrian related maxillofacial fractures in their study.

While RTC have been steadily falling in the developed countries, they continue to rise with horrifying speed in the low and middle-income (LMIC) countries of Africa and Asia [62]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has estimated that nearly 25% of all injury fatalities worldwide are a result of road traffic crashes, with 90% of the fatalities occurring in LMIC [62]. The reductions in RTC in developed countries are largely attributed to a wide range of road safety measures such as seat belt use, traffic calming measures and traffic law enforcement. Therefore, there is an urgent need to get down to what the developed nations have done to reduce/prevent road traffic crashes.

Assaults and falls were the second most common cause of maxillofacial injuries in adults and children respectively in all centres except the north eastern part of the country, where assaults remained a major cause (Table II). Other common causes were sport injuries, industrial accidents and animal attacks. Fasola et al [18] in Ibadan (SW) reported an increase in number of maxillofacial injuries due to assaults, falls, sporting injuries and industrial accidents between 1978 and 1999 by a factor of 1.4, 1.5, 3.5, and 1.5 respectively. Increase in number of assaults related maxillofacial injuries could be attributed to the poor socioeconomic conditions of the country leading to stress and propensity to crime. In fact, the employment rate among college and university graduates has increased from 4% during the early 1970s to 45% currently [4]. Furthermore, the poor capital income of an average Nigerian has decreased by 75% during the past 20–25 years [4,63]. The prevalence of assaults related injury in north eastern Nigeria could be attributed to nomadic form of life style in this region, where animals are moved over several kilometres of land grazing without strict laws guiding their movement thereby destroying cash crops [53]. This frequently led to fights between farmers and cattle men, and various objects such as cutlasses/machetes, arrows and wooden objects are used in inflicting injuries during fight [4,53]. This is unlike European and American studies where most of the fights occurred in the streets, clubs and pubs [6,7,10,11].

Also, the increase in maxillofacial injuries due to sports injuries and industrial accidents could be attributed to increase involvement of Nigerians in recreational and professional sport activities, and increase in the numbers of industries over the years without corresponding increase in protective measures. Onyeaso and Adegbesan [64] in a survey among Nigerian sport persons reported that only one-third of them ever used protective elements during sporting activities, whereas about 60% of them have had one form of orofacial injury or the other before.

Maxillofacial skeletal and soft injuries due to animal attacks were not infrequent, especially in northern part of the country [4,51,52]. While dogs remain the animals most commonly implicated in other reports [65,66], cows, camels and donkeys were mostly involved in Nigeria, because cattle rearing and use of animals as "beasts of burden" are still prevalent practices in northern part of Nigeria [4,51,52].

The peak age of incidence of maxillofacial injuries of 21–30 years among Nigerians is not different from reports from other parts of the world [5-10,12-14,57]. The possible explanation for this is that people in this age group take part in dangerous exercises and sports, drive motor vehicles carelessly, and are most likely to be involved in violence [16].

More males were involved in maxillofacial injuries than females in agreement with previous reports [5-10,13,14]. However, a tendency towards an equal male-to female ratio was observed between earlier and later studies in most centres across the country. This can be attributed to a changing workforce. Women, who are used to stay at home, now work in outdoor and high-risk occupations, thus becoming exposed to RTC and other causes of maxillofacial injuries [18,50].

Most of the fractures of maxillofacial skeleton in Nigerian patients were of the mandible, the findings comparable to other reports [9,12-14]. The mobility of the mandible and the fact that it has less bony support than the maxilla have been implicated [16,67]. Dentoalveolar and condylar fractures were reported to be less in Nigerian patients [1,9,12-14,54]. Dental/dentoalveolar injury is frequently overlooked in surveys that review maxillofacial injury [68-70]. Only the analysis of a large number of injuries reveals the risk of suffering from dentoalveolar trauma [68-70]. Gassner et al [69] in a large series of 9,543 patients with 21,067 maxillofacial injuries reported an incidence of 49.9% of dentoalveolar injuries among their patients. Gassner et al [70] in another large series of craniomaxillofacial trauma in 3,385 children younger than 15 years of age reported an incidence of 76.3% cases of dentoalveolar injuries. Midfacial bone fractures especially LeFort types and orbital floor fractures were reported to be commoner than mandibular fractures [69,70] in contrast to Nigerian reports. A low utilization of technological advances in the imaging of maxillofacial fractures (e.g. CT Scan) in Nigeria may be partially responsible for the observed difference. The midfacial skeleton is much more difficult to assess using plain films than is the mandible [71]. The presence of thin bones, fluid-filled spaces (e.g. congested sinuses), and soft tissues (e.g. orbital contents) make accurate assessment difficult with images that do not offer a high degree of contrast [71]. The difference in the incidence of middle-third fractures has also been related to the refusal of Nigerian motorists to use safety devices, which has reduced their survival after severe middle-third fractures [50].

Although, open reduction and internal fixation remains the "gold standard" of treatment of maxillofacial fractures [72,73], this form of treatment however, has not become popular in our environment [1,50]. Presently, the full compliment of equipment and materials for rigid fixation is not readily available in all parts of the country; and where available, the cost of treatment is usually quite prohibitive [45]. Previous Nigerian reports have, however attested to the satisfactory results obtained using simple conservative methods of closed reduction and mandibulo-maxillary fixation [1,4,16,19,21,25,32,36,45,50,54].

Conclusion

No apparent shift from road traffic crashes as the leading cause of maxillofacial injuries in Nigeria over a period of 40 years was observed, unlike in most developed countries where assaults/interpersonal violence has replaced road traffic crashes as the major cause of the injuries. Injuries have causes, they do not simply befall us from fate or bad luck. Since no magic pill is envisaged for the prevention of road traffic crashes, we need to take good stock of all the tools at our disposal, and to get down to what the developed nations have done to reduce/prevent road traffic crashes. Therefore, an awareness campaign to educate the public about the importance of restraints and protective headgear in cars and motorcycles should be championed. These findings should also alert the authorities, particularly the government and the Road Safety Commission to the need for the provision of good roads, enforcement of existing traffic laws, and general improvement of socioeconomic condition of the populace.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare they have no competing interest.

Authors' contributions

WLA conceived the study and did the literature search, coordinated the write-up and submission of the article. WLA, ALL, MOO and OJ participated in the writing of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the followings: Prof. J.A. Akinwande, Dr. A.O.Fasola, Prof. V.I. Ugboko, Dr. H.O. Olasoji, Dr. G.T. Arotiba and Dr. J.T. Arotiba, for their assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Wasiu Lanre Adeyemo, Email: lanreadeyemo@yahoo.com.

Akinola Ladipo Ladeinde, Email: drakinladeinde@yahoo.com.

Mobolanle Olugbemiga Ogunlewe, Email: gbemilewe@yahoo.co.uk.

Olutayo James, Email: olutayojames@yahoo.com.

References

- Ugboko VI, Odusanya SA, Fagade OO. Maxillofacial fractures in a semi- urban Nigerian teaching hospital. A review of 442 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;27:286–289. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80616-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihlbert JK. Head injury in automobile accidents. Automobile Injury Research Report. 1965. No VJ-1823-R17.

- Nahum AM, Siegel AW, Brooks S. Proc 14th STAPP Car Conference. New York: Society of Automobile Engineers; 1970. The reduction of collision injuries. Past, present and future; pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Olasoji HO, Tahir A, Arotiba GT. Changing picture of facial fractures in northern Nigeria. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;40:140–143. doi: 10.1054/bjom.2001.0716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AA. A retrospective study of injuries to the maxillofacial skeleton in Harare, Zimbabwe. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;26:435–439. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(88)90098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magennis P, Shepherd J, Hutchison I, Brown A. Trends in facial injuries: increasing violence more than compensate for decreasing road trauma. BMJ. 1998;316:325–332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7128.325a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoof RF, Mrérlex CA, Stekelenberg EC. The different pattens of fractures of the facial skeleton in four european countries. Int J Oral Surg. 1977;6:3–11. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(77)80066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afzeilus LE, Rosen C. Facial fractures: A review of 368 cases. Int J Oral Surg. 1980;9:25–33. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(80)80003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RD, Cowpe JG. Patterns of maxillofacial trauma in two different cultures. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1985;30:299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RE, Scianna JM, Petruzzelli GJ. Mandible fracture patterns: a suburban trauma center experience. Am J Otolaryngol. 2004;25:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laski R, Ziccardi VB, Broder HL, Janal M. Facial trauma: a recurrent disease? The potential role of disease prevention. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:685–688. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari MH. Maxillofacial fractures in Hamedan province, Iran: a retrospective study (1987–2001) J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2004;32:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Ahmed HE, Jaber MA, Abu Fana SH, Karas M. The pattern of maxillofacial fractures in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates: a review of 230 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;98:166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erol B, Tanrikulu R, Gorgun B. Maxillofacial fractures: Analysis of demographic distribution and treatment in 2901 pateints (25-year expereience) J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2004;32:308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oji C. Maxillofacial injuries. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97:866–868. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199604000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oji C. Jaw fractures in Enugu, Nigeria, 1985–1995. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;37:106–109. doi: 10.1054/bjom.1997.0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwoku AL, Oluyadi BA. Retrospective analysis of 1206 maxillofacial fractures in an urban Saudi hospital: 8 year review. Pakistan Oral Dent J. 2004;24:13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Fasola AO, Nyako EA, Obiechina AE, Arotiba JT. Trends in the Characteristics of Maxillofacial Fractures in Nigeria. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1140–1143. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(03)00671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasola AO, Obiechina AE, Arotiba JT. An audit of midfacial fractures in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2001;30:183–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telfer MR, Jones GM, Shepherd JP. Trends in the aetiology of maxillofacial fracture in the United Kingdom (1977–1987) Br J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 1991;29:250–255. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(91)90192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajagbe HA, Daramola JO, Oluwasanmi JO. Civilian-type facial injuries- A retrospective study of cases seen at the University College Hospital, Ibadan. Nigerian Med J. 1977;7:432–436. [Google Scholar]

- Abiose BO. Maxillofacial skeleton injuries in the Western states of Nigeria. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;24:31–39. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(86)90037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyako AE. Review of facial fractures at the University College Hospital Ibadan (1978–1982) Thesis, West African Postgraduate Medical College, Lagos, Nigeria; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Fasola AO, Lawoyin JO, Obiechina AE, Arotiba JT. Inner city maxillofacial fractures due to road traffic accidents. Dent Traumatol. 2003;19:2–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-9657.2003.00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasola AO, Denloye OO, Obiechina AE, Arotiba JT. Facial bone fractures in Nigerian children. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2001;30:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasola AO, Obiechina AE, Arotiba JT. Fractures of the mandible in children. East Afr Med J. 2001;78:61–3. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v78i11.8954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasola AO, Obiechina AE, Arotiba JT. Incidence and pattern of maxillofacial fractures in the elderly. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32:206–208. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasola AO, Obiechina AE, Arotiba JT. Sports related maxillofacial fractures in 77 Nigerian patients. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2000;29:215–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasola AO, Obiechina AE, Arotiba JT. Concomitant injuries in 531 patients with maxillofacial fractures. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2002;31:101–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasola AO, Obiechina AE, Arotiba JT. Soft tissue injuries of the face: a 10 year review. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2000;29:59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasola AO, Obiechina AE, Arotiba JT. Zygomatic complex fractures at the University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 2002;79:137–139. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v79i3.8892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abiose BO. The incidence and management of middle third facial fractures at the University Teaching Hospital, Ibadan. East Afr Med J. 1991;68:164–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denloye OO, Fasola AO, Arotiba JT. Dental emergencies in children seen at University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan, Nigeria- 5 year review. Afr J Med Med Sci. 1998;27:197–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajagbe HA, Daramola JO. Pattern of facial bone fractures seen at the University Teaching Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria. East African Med J. 1980;57:267–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankole OO, Fasola AO, Denloye OO. Oro-facial soft tissue injuries in Nigerian children: a five-year review. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2004;33:93–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwoku AL, Akinosi JO, Solarin EO, Obisesan BA. Results of out-patient treatment of mandibulo-maxillary fractures in LUTH. Niger Med J. 1979;9:100–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinwande JA. Fracture of the mandible due to road traffic accidents in Lagos, Nigeria. Nig Dent J. 1990;9:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Arotiba GT. Facial fractures due to road traffic accidents in Lagos. Niger Med J. 1996;30:66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Arotiba GT. The aetiology of facial fractures in Lagos. Niger Postgrad Med J. 1996;3:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Akinwande JA, Ogunbanjo B, Ladeinde A, Ogunlewe O, Obisesan B, Oluseye T. Armed robbery gunshot injuries to the maxillofacial region. Journal clinical Practice. 1998;1:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Odusanya SA. Maxillofacial fractures in South Western Nigeria (1976–1981) Odontostomatologie Tropicale. 1985;3:153–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugboko VI, Owotade FJ, Oginni FO, Odusanya SA. Gunshot injuries of the orofacial region in Nigerian civilians. SADJ. 1999;54:418–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oginni FO, Akinwande JA, Fagade OO, Arole GF, Odusanya SA. Facial dog bites in Southwestern Nigerian children. An analysis of eight cases. Trop Doc. 2002;32:239–240. doi: 10.1177/004947550203200423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oginni FO, Fagade OO, Akinwande JA, Arole GF, Odusanya SA. Pattern of soft tissue injuries to the oro-facial region in Nigerian children attending a teaching hospital. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2002;12:201–206. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263X.2002.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugboko V, Udoye C, Ndukwe K, Amole A, Aregbesola S. Zygomatic complex fractures in a suburban Nigerian Population. Dent Traumatol. 2005;21:70–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2004.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugboko V, Odusanya S, Ogunbodede E. Maxillofacial fractures in children: An analysis of 52 Nigerian cases. Ped Dent J. 1998;8:31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Adekeye EO. The pattern of fractures of the facial skeleton in Kaduna, Nigeria. A survey of 1,447 cases. Oral Surg. 1980;6:491–495. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(80)90068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adekeye EO. Fractures of the zygomatic complex in Nigerian patients. J Oral Surg. 1980;38:596–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adekeye EO. Pediatric fractures of the facial skeleton: a survey of 85 cases from Kaduna, Nigeria. J Oral Surg. 1980;38:355–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adebayo ET, Ajike OS, Adekeye EO. Analysis of the pattern of maxillofacial fractures in Kaduna, Nigeria. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;41:396–400. doi: 10.1016/S0266-4356(03)00165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugboko VI, Olasoji HO, Ajike SO, Amole AOD, Ogundipe OT. Facial injuries caused by animals in northern Nigeria. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;40:433–437. doi: 10.1016/S026643560200181X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunbodede EO, Arotiba JT. Camel bite injuries of the orofacial region: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55:1174–1176. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(97)90303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olasoji HO. Maxillofacial injuries due to assault in Maiduguri, Nigeria. Trop Doc. 1999;29:106–108. doi: 10.1177/004947559902900216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olasoji HO, Tahir A, Bukar A. Jaw fractures in Nigerian children: an analysis of 102 cases. Cent Afr J Med. 2002;48:109–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oji C. Fractures of the facial skeleton in children: a survey of patients under the age of 11 years. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1998;26:322–325. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(98)80062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saheeb BDO, Etetafia MO. Influence of positions on the incidence and severity of maxillofacial injuries in vehicular crashes. West Afr J Med. 2003;22:146–149. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v22i2.27936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beek GJ, Merkx CA. Changes in the pattern of fractures of the maxillofacial skeleton. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;28:424–428. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0020.1999.280605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontio R, Suuronen R, Ponkkonen H, Lindqvist C, Laine P. Have the causes of maxillofacial fractures changed over the last 16 years in Finland? An epidemiological study of 725 fractures. Dent Traumatol. 2005;21:14–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2004.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus JF, Riggins RS, Franti CE. Some epidemiological features of motorcycle collision injuries. Am J Epid. 1975;102:74–113. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deaner RM, Fitchett VH. Motorcycle trauma. J Trauma. 1975;15:678–681. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197508000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adegbehingbe BO, Oluwadiya KS, Adegbehingbe OO. Motorcycle associated ocular injuries in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. African Journal of Trauma. 2004;2:35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kobusingye OC. Why poor countries cannot afford to ignore road safety. African Journal of Trauma. 2004;2:6. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson S. Hope for Nigeria. Newsweek International. 1999;7:23. [Google Scholar]

- Onyeaso CO, Adegbesan OA. Orofacial injury and mouthguard usage by athletes in Nigeria. Int Dent J. 2003;53:231–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2003.tb00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff KD. Management of animal bite injuries of the face: expereience with 94 patients. J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 1998;56:838–843. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(98)90009-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourie L, Cartilidge D. Fracture of the maxilla following dog bite to the face. Injury. 1995;26:61–62. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(95)90557-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly DE, Harrigan WE. A survey of facial fractures: Bellevue Hospital, 1948–1974. J Oral Surg. 1975;33:146–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuli T, Hachl O, Rasse M, Kloss F, Gassner R. Dentoalveolar trauma analysis of 4763 patients with 6237 injuries in 10 years. Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 2005;July 2 doi: 10.1007/s10006-005-0629-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassner R, Tuli T, Hachl O, Rudisch A, Ulmer H. Cranio-maxillofacial trauma: a 10 year review of 9,543 cases with 21,067 injuries. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2003;31:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(02)00168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassner R, Tuli T, Hachl O, Moreira R, Ulmer H. Craniomaxillofacial trauma in children: a review of 3,385 cases with 6,060 injuries in 10 years. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis E, 3rd, Scott K. Assessment of patients with facial fractures. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2000;18:411–448. doi: 10.1016/S0733-8627(05)70137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz SR, Ziccardi VB, Borah G. Current therapy: complications associated with rigid internal fixation of facial fractures. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2005;26:565–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Sickels JE. A review and update of new methods for immobilisation of the mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:S11–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]