Abstract

The human pathogen Streptococcus pyogenes secretes many proteins to the cell wall and extracellular environment that contribute to virulence. Rgg regulates the expression of several exoproteins including a cysteine protease (SPE B), a nuclease (MF-1), a putative nuclease (MF-3), and autolysin. The functional heterogeneity of Rgg-regulated exoproteins and the lack of a conserved regulatory motif in the promoter regions of the genes suggested that Rgg interacts with additional regulatory networks to influence gene expression. DNA microarrays were used to test this hypothesis by comparing genomewide transcript profiles of S. pyogenes NZ131 and isogenic derivative NZ131 rgg during the exponential phase of growth. Transcripts of known and putative virulence-associated genes were more abundant in the rgg mutant, including emm, scpA, orfX, scl1, hasAB, slo, sagA, ska, speH, grab, mac, mf-1, and mf-3. Increased transcription of emm, scpA, and orfX in the rgg mutant was associated with increased production of the corresponding proteins. Differences in the expression of virulence-associated genes were associated with changes in the expression of several regulatory genes, including mga, sagA, csrRS, and fasBCA. The results show that Rgg influences the expression of multiple regulatory networks to coregulate virulence factor expression in S. pyogenes.

Human infection with Streptococcus pyogenes may result in a variety of diseases, including pharyngitis, impetigo, toxic shock syndrome, necrotizing fasciitis, rheumatic fever, and acute glomerulonephritis. S. pyogenes secretes many proteins to the cell wall and extracellular environment that directly influence host-pathogen interactions. Although several of these proteins have been studied in detail, the functions of many of them are not known. Insight into the functions of secreted proteins can be gained by identifying coordinately regulated genes, which are likely to have related functions. In addition, identification of virulence-associated regulatory networks may lead to new therapeutic strategies designed to minimize severe disease by inhibiting the expression of virulence-associated genes.

Several transcriptional regulators have been described in S. pyogenes that influence the expression of secreted proteins. Among these, Mga is the most thoroughly studied. Mga coordinates expression of colinear genes encoding proteins involved in adherence and the ability to resist phagocytosis. These include the M protein (emm), C5a peptidase (scpA), OrfX (orfX), and in certain serotypes, M-related proteins such as Mrp (mrp) and Enn (enn; 5, 22, 35, 38, 42, 47). Mga activates transcription by binding to defined response elements in the promoter regions of mga, emm, and scpA (31, 34). Mga also activates transcription of genes located elsewhere in the chromosome, including sof, which encodes a fibronectin-binding lipoproteinase designated SOF (35, 44), and scl1, which encodes a collagen-like adhesin, Scl1 (28, 45). Mga is considered to be the primary transcriptional activator of these genes; however, other uncharacterized factors also influence expression (34).

Inactivation of regulatory genes that influence expression of secreted proteins often results in a pleiotropic phenotype. For example, inactivation of the two-component regulator designated CsrRS, also known as CovRS, enhanced expression of hasAB, which are required for hyaluronic acid capsule biosynthesis and speB, mf-1, and sagA (3, 14, 17, 25). The speB gene encodes a secreted cysteine protease (SPE B) that contributes to virulence in mouse models (21, 27, 29), and mf-1 encodes a secreted nuclease (MF-1) previously described as DNase B (49). The sagA locus (also known as pel) has regulatory activity and encodes streptolysin S (4, 26). Inactivation of sagA decreased expression of emm, speB, and ska, which encodes the secreted plasminogen activator streptokinase (26). Nra influences expression of prtF2 (encoding a fibronectin binding protein), cpa (encoding a collagen binding adhesin), and mga (41). Nra has an amino acid sequence similar to that of RofA, which is a positive regulator of the fibronectin binding protein encoded by prtF1 (16), and also affects expression of mga, emm, sagA, and speA, which encodes a secreted superantigen, SPE A (1). A two-component regulator composed of two histidine kinases (FasB and FasC) and a response regulator (FasA) influences expression of ska and sagA (20). These findings suggest that multiple regulatory networks interact to coordinate expression of virulence-associated genes in S. pyogenes.

Complex regulation may result from the influences of multiple regulatory networks on gene expression. For example, transcription of speB is abolished in rgg (ropB) mutants (6, 30), decreased in mga (42) and sagA (26) mutants, and enhanced in a csrR mutant (17). Inactivation of dipeptide and oligopeptide transport operons decreases speB expression (39, 40), and SPE B production is influenced by the growth phase and the concentration of glucose in the medium (9). Such intricate regulation of gene expression may be particularly important for proteins, such as SPE B, that can cause significant destruction of host tissues.

Rgg was initially identified in S. pyogenes as being required for the expression of speB (6, 30). Recently, Rgg was discovered to influence the expression of additional exoproteins, including autolysin, MF-1, and MF-3 (10). The absence of a conserved regulatory motif in the promoter regions of Rgg-regulated genes and the functional diversity of the gene products suggested that Rgg interacts with additional regulatory networks to alter gene expression. DNA microarrays and quantitative RT-PCR were used to identify and quantitate genomewide changes in transcription associated with inactivation of rgg. The results demonstrate that Rgg interacts with other regulatory networks to influence the expression of several genes known to mediate interactions of S. pyogenes with its human host.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

S. pyogenes NZ131 (serotype M49) and the isogenic derivatives NZ131 speB and NZ131 rgg have been previously described (6, 8). S. pyogenes was grown with Trypticase soy agar containing 5% sheep blood agar (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.) overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2 or with Todd-Hewitt broth containing 0.2% (wt/vol) yeast extract (THY; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.).

RNA isolation.

S. pyogenes was grown in 10 ml of THY broth in 15-ml tubes (Corning, New York, N.Y.) for 2 to 3 h (A600 = 0.2). Cultures were centrifuged, and the bacteria were suspended in 200 μl of diethyl pyrocarbonate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.)-treated water and frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA was isolated with a FastPrep Instrument (Qbiogene, Carlsbad, Calif.) and a FastPrep Blue kit (Qbiogene) as previously described (10).

DNA microarray analysis.

DNA microarrays were prepared and analyzed as previously described (48). Briefly, internal regions (approximately 500 bp) of 1,893 open reading frames identified by WIT2 analysis (wit.mcs.anl.gov/WIT2) of the S. pyogenes SF370 (serotype M1) genome (15) were amplified by using open reading frame-specific primers designed with Primer3 software (http://wwwgenome.wi.mit.edu). The PCR products were printed in quadruplicate on CMT-GAPS slides (Corning) with a Chipwriter robotic arrayer (Virtek, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada). Fluorescently labeled cDNA probes were prepared with an ARES DNA labeling kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.). Probes were denatured at 100°C for 5 min and hybridized with microarrays in 100 μl of PerfectHyb solution (Sigma) at 55°C for approximately 18 h. The arrays were washed twice in 0.1× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)--0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 10 min at room temperature and twice in 0.1× SSC. The slides were scanned with a ScanArray 5000 instrument (Packard Bioscience, Meriden, Conn.), and the data were analyzed with QuantArray software (Packard Bioscience) as previously described (48).

Quantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR.

Oligonucleotide primers and probes (Table 1) were designed with Primer Express 1.0 software (ABI Prism; PE Biosystems, Framingham, Mass.) and purchased from either MegaBases Inc. (Evanston, Ill.) or PE Biosystems. Amplification and detection were done with the ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System (PE Applied Biosystems) by using TaqMan One-Step RT-PCR Master Mix Reagents (PE Biosystems) as described by the manufacturer. Each assay was done in triplicate with at least two independently isolated RNA samples. Amplification and analysis were done as previously described (10). The quantity of cDNA for each experimental gene was normalized to the quantity of gyrA cDNA in each sample, and the mean ± the standard error of the mean of independently isolated RNA samples is reported.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers and fluorescent probes used for TaqMan RT-PCR

| Accession no. | Designationa | Forward primer (5′-3′) | Reverse primer (5′-3′) | Fluorescent probeb (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF057697 | sof49 (SOF) | CACTACAAAGACGATTGGTGCTAAA | CAACACCCCAGTCCCAATCT | TAGAGGAAGTTTGGGAGCAGGCCAAAA |

| M31789 | emm49 (M49) | GCATCCGTAGCGGTCGC | CAGCAGCCTTAACTTCTGTTTGG | TGGCTGTTTTAGGAGCAGGCTTTGCA |

| X68501 | mga49 (Mga) | GCTCAATCTCAGCATCACCAATAA | AATGTCTTCTTCGTCTAACACCGA | ACGAAGTTGCCGTAACCCTCCATAACG |

| X72753 | enn (Enn) | AGCACCAAAAATTAGAGGCTGATC | GATGCTTCAAGGTCACGGCT | CCAAGTTTCAGAGACTAGCCGCAAGGG |

| X78055 | scpA49 (C5a peptidase) | AAACGAAAGAACCTTACCGCC | CGACACGCATCAAAAGCAA | AGAAGGTGCGATGCCTGAGGCTCA |

| X80397 | orfX (OrfX) | TCTACTGAGTCTACTACTCAGCCAGTTGA | TGTCACCATCGAATCTGAAGCT | CACCCGTGCAGGAGACACAGGC |

| SPy0167 | slo (SLO) | GAAATATCCGTATCATGGCTAGAGAGT | CACATCTCTTTCGTCGATCACTTT | GCCACCATTCCCAAGCTAAGCCAGTG |

| SpyO212 | speG (SpeG) | TTCTATTGTATCTTTAGGCATTACTGATCA | TTCGAATGTTTTACAATACCACCATAA | CGATGTTTTTGGTCTCCCTTATAATTTTTCCCC |

| SPy0242 | fasB (FasB) | TGAGCCGTATAGAGCGTTTAGGT | TCATGAACCGTTTGGGCATA | AAGCCATTAAGAGTGAATCCATTACTCAGATTCAAGA |

| SPy0244 | fasC (FasC) | CACAAAAACCAATCGTGTGGATA | CAGTCAAAAAGTGGGCTGAGTTC | AGCCAAACGCTTTGATGCTCAGCAG |

| SPy0245 | fasA (FasA) | CGTTGTGGGCTTGAATTAGCT | ATTCTGAATGAGTGGTGACAAACAC | CAGCTATTCGACAAAAAGATCCTAATGCCGTTAT |

| SPy0336 | csrR (CsrR) | GGTGCAGACGACTATATTGTTAAACCC | TTGACGGCGGAAAATAGCA | TTTGCCATTGAAGAACTACTTGCCCGTATTC |

| SPy0337 | csrS (CsrS) | CCTGGCTTGCATGGTCCTA | CATGGAAAACCCACGATACTGA | CGGTCGTGTGTATCACGACCATATCGA |

| SPy0528 | vicR (VicR) | ACGTGACCAAGCCCTTTTCTAA | TTCGGTACGACGCAGATGAG | CACGCGCCAGCAATTCCCG |

| SPy0529 | vicK (VicK) | GCGCTTTGCGTTGAATAGG | TCCTGTTCTGTGGTGTCATGGA | CCACAACCAAGCCCGAAATAAAACCACT |

| SPy0738 | sagA (SLS) | TTGCTCCTGGAGGCTGCT | CTTCCGCTACCACCTTGAGAAT | ACCACTTCCAGTAGCAATTGAGAAGCAACAAG |

| SPy0747 | None (none) | TTGTGTGCAACCAGTCACTTTTAA | TCTTTCGCAAATTGTGCTAGCA | TCTGAGCAAAGACGTCACGTCTTGGCTA |

| SPy0861 | mac (Mac) | ACTTCCGTTTGGACCAAAGGA | CAACATAAGGAGCGTGAAAAACATC | TTACTCCTCCAGCAAACTTCACTCAAGGTGA |

| SPy0874 | trcR (TrcR) | TGGCAGATGTCTAATGTTTTGACA | TGCCTCTTGACCGTTAAAAACC | CTGCCATGACTCATCAAGGTTATGACGTTG |

| SPy0875 | None (none) | TTCCGGTATGGTCATCAAACC | ACTCGTGGCCTGCATTAGTAATAA | GCGACGCTGCTTCTCAGAATTTTGGACA |

| SPy0895 | deoD2 (DeoD2) | TTGCCTTTCTAGCGGAACATG | GCGATTGGTTAAGCCATAATGAAC | CAGAGAATCGGACCATTGAAGACCAGTATCAC |

| SPy0898 | cpsY (CpsY) | CACAACTCCTTTTATTTTTCAGAAGAGA | GCACGGTCACTGACCACAAT | ATGTCCCAGATGCCCCACAACAAATC |

| SPy1008 | speH (SpeH) | TCACAGGAATTCAAAGATAAAGAAGTAGA | CAAACGCTTCATACCTTTTCCC | ATTTATGCTCTATCTGCACAAGAGGTTTGTGAATGT |

| SPy1061 | yesN (YesN) | GTTATCATTGTTGCTAATTGGTCTTTTTAT | GGTTGCAGTGGCATTGATATCA | TCATTAGCGCCACAACAATTAGGCCTCTATC |

| SPy1062 | yesM (YesM) | TTGGAGTGGGTACATGCTCATT | AACTCTCACTATACCCTAAGTCATGAGCTA | TCAAGACAAGATCAGCACGAGCCGC |

| SPy1106 | yufM (YufM) | GCAATGGGATTCAATTTTTGGA | ATTTGCGGCTGAAATAATAATGACT | AAATGGCGTACTCAGCATATTCCTTGCG |

| SPy1236 | ciaS (CiaS) | GGTCCAGGGATAACAGATGAAGAA | CCACCTGTTTGCCGTGTTC | AGCTTGTCAACTCGATAAAAACGATCAAAAATCTTT |

| SPy1237 | ciaR (CiaR) | GATCATGACAGCTAAAGAGGGTTTAGA | AATAGAACGGCTTTGTCAGATAATCA | CAGCACCTAATTCAAATCCGTGGCCTT |

| SPy1357 | grab (Grab) | GCATCAGTATTAGTCGGTTCAACAGT | CCGCCATTTGGAATAATTCG | TCTGCTGTTGACTCACCTATCGAACAGCC |

| SPy1436 | mf-3 (MF-3) | TCCTCCTGGCTGGCATAATT | CTAAATGGCCACGGTCCATT | AAATTGACTGACGCTAATGGAAAAACAACTTGG |

| SPy1556 | zmpS (ZmpS) | AAAAGAAGTATCAGCAATAGCAATGG | TGCTGAGCCAAGCTTTTTAGG | TCAAATCAGAATCTGCCAACCGCTCA |

| SPy1587 | lytR (LytR) | GATTTTACAAGGGCTCACCATGA | TGCCTGATCTTGCTGTTTGAA | ACTTCAAATCCAAGTGCCTGCCAATCA |

| SPy1588 | lytS (LytS) | TTTACCTCCGTCTCTTTCATCATTT | AAGCCACCATTTGGCTCCTT | CGAGACAGGGTTTCTTGGTCCATGGC |

| SPy1801 | isp-2 (Isp-2) | CGTCGCGCACAAATTATGG | GGCTGGAATGGCTGGTGT | CCATGGTCATCAATCCACTTATCCAGGTCT |

| SPy1908 | salR (SalR) | TTGATGACCACAGACTATTTGCAA | ACATCGTTAAAATGAGAAGTAATCGTATCT | CCAACTGTTATTCCAACAGTATGATGAAGTAGATGTCA |

| SPy1909 | salK (SalK) | GGATTGTACTCATGAAGGTATTAGTTAAAGA | TTGGAGTTTTCTAAATAATAAAAGATGCA | GAAATTACCACTAGACAAAACAACGTGCTTGCGT |

| SPy1979 | ska (SKA) | TGCTGACAAAGATGGTTCGG | GCACATGTCCCTTTAACAAAAATTC | ACCTTGCCGACCCAACCTGTCCA |

| SPy1983 | scl1 (Scl-1) | CAAACTAGTCTGGCGCTACGG | TTGCCCCGCCTCCAA | CCTCAGCCGCTGCCGTCCTTCT |

| SPy2025 | isp-1 (Isp-1) | GCAGCGCAAGCCAGGTT | CTTGGCCTGGTGCAAATGA | ACCACCCATAAACCTAAAGTGGGCTA |

| SPy2026 | ihk (Ihk) | GGTGACTTTGCAGATCGTGACA | TTGAACCAGTTGGGCTTGC | AAGGACGTCTCGGCACTTTCGCAAATAT |

| SPy2027 | irr (Irr) | TCGAAAATGTATTACGCGTCTCTACT | CGCTATGTTCGGTCTCATCAAC | CAGATGAAAAGCGCCAAATCGGAGACTTAC |

| SPy2043 | mf-1 (MF-1) | CCCAAAATGTAGGAGGTCGTG | CATTCTTGAGCTCTTTGTTCGGT | CCAAAAAGGCGGCATGCGCT |

| SPy2200 | hasA (HasA) | ACCGTTCCCTTGTCAATAAAGG | CGTCAGCGTCAGATCTTTCAAA | CGCCATGCTCAAGCGTGGGC |

| SPy2201 | hasB (HasB) | GAATCGAGAAAATTAAATAGTCACATGATT | CCTCCATAACCAAATGATGGGT | TTCAAGGAATTTCTTATGATGATCGAATAGGAATGC |

| SPy2202 | hasC (HasC) | TGAAACCACTGCCATTAACCTTC | GCTTGTAAGACAGCATCTCCCA | TTTTATCCGTCAAAGCCACCCAAGAGG |

Gene designations are shown in italics, and the corresponding protein designations are in parentheses.

Covalently linked at the 5′ end to 5-carboxyfluorescein and at the 3′ end to N,N,N-tetramethyl-6-carboxyrhodamine.

Immunoblot analysis.

Immunoblotting was done as previously described (7). Briefly, 108 streptococci, determined by dilution plating and enumeration of CFU per milliliter, were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with a 10% acrylamide resolving gel. Following electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.) with Towbin's buffer (50). Antisera to M49 (provided by J. B. Dale, Department of Medicine, University of Tennessee, Memphis), C5a peptidase (provided by P. P. Cleary, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis), and OrfX (provided by B. Lei, Laboratory of Human Bacterial Pathogenesis, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, Hamilton, Mont.) were used at a dilution of 1:1,000. The antibody-antigen complexes were visualized with the enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Inc., Piscataway, N.J.).

RESULTS

Inactivation of rgg increases transcription of several virulence-associated genes.

DNA microarrays and cDNA prepared from exponential-phase cultures of S. pyogenes NZ131 and NZ131 rgg were used to identify genomewide differences in virulence-associated gene transcripts. Transcripts of several genes encoding known or putative virulence factors were more abundant in the rgg mutant (Table 2), including well-characterized virulence factors such as M protein, C5a peptidase, streptolysin S, and streptolysin O (slo). Transcripts of recently characterized genes likely to contribute to host-pathogen interactions were also more abundant in the mutant, including (i) scl1, which encodes an adhesin (28, 45), (ii) speH, which encodes a superantigen (43), (iii) grab, which encodes a cell wall-associated protein that binds human α2-macroglobulin to inhibit protease activity (46), and (iv) mac, which encodes a secreted protein that inhibits opsonophagocytic killing of S. pyogenes (24).

TABLE 2.

Increased transcripts of virulence-associated genes in rgg mutant strain NZ131 identified with DNA microarrays

| SPy no. | Designationa | Mean fold difference ± SEMb |

|---|---|---|

| 0167 | slo (SLO) | 2.1 ± 0.1 |

| 0738 | sagA (SLS) | 2.1 ± 0.1 |

| 0747 | None (none) | 1.6 ± 0.1 |

| 0861 | mac (Mac) | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| 1008 | speH (SpeH) | 1.5 ± 0.2 |

| 1357 | grab (Grab) | 1.6 ± 0.0 |

| 1436 | mf-3 (MF-3) | 8.8 ± 0.3 |

| 1983 | scl1 (Scl-1) | 3.3 ± 0.2 |

| 2010 | scpA (C5a peptidase) | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| 2018 | emm (M) | 1.9 ± 0.1 |

| 2043 | mf-1 (MF-1) | 2.8 ± 0.3 |

Gene designations are in italics, and the corresponding protein designations are in parentheses.

The mean difference ± the standard error of the mean (rgg mutant strain NZ131 versus wild-type NZ131) in intensity of quadruplicate spots is shown.

The role of secreted nucleases in the pathogenesis of S. pyogenes infection has not been established. However, the toxicity of cytolethal distending toxin of Campylobacter jejuni is dependent on its nuclease activity (23). Transcripts of a known and putative extracellular nucleases, including mf-1, mf-3, and spy0747, were more abundant in the rgg mutant (Table 2).

Inactivation of rgg enhances expression of the Mga regulon.

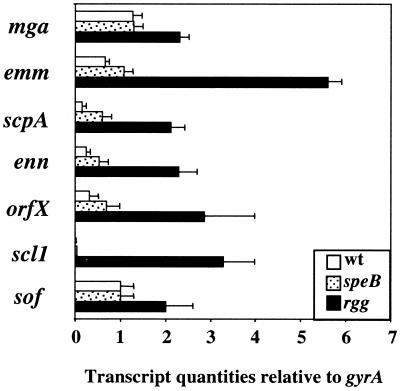

Increased transcripts of the Mga-regulated genes emm, scpA, and scl1 in the rgg mutant (Table 2) suggested that Rgg represses expression of the Mga regulon. To test this idea, quantitative RT-PCR was used to quantitate Mga-regulated gene transcripts, including mga, emm, scpA, enn, orfX, scl1, and sof. Transcripts of each gene were more abundant in the rgg mutant than in the isogenic wild-type strain (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Increased transcription of the Mga regulon in NZ131 rgg. Total RNA was isolated from exponential-phase cultures of wild-type (wt) NZ131, speB mutant strain NZ131, and rgg mutant strain NZ131, and the quantities of gene-specific transcripts were determined by quantitative RT-PCR. The quantity of cDNA for each gene was normalized to the quantity of gyrA cDNA in each RNA sample. The values shown are the mean ± the standard error of the mean of at least two independently isolated RNA preparations analyzed in triplicate.

Transcripts of rgg are more abundant in NZ131 speB than in the isogenic wild-type strain (10). This observation suggested that inactivation of speB or the lack of speB expression in the mutant could alter the transcription of genes other than speB. Because the rgg mutant does not express speB, it was theoretically possible that differences in expression in the rgg mutant resulted from a lack of speB expression. To assess this possibility, the quantities of Mga-regulated gene transcripts were determined in strain NZ131 speB. The quantities of gene transcripts in NZ131 speB were similar to those in the isogenic wild-type strain, albeit slightly elevated (Fig. 1). The results show that increased transcription of Mga-regulated genes in the rgg mutant was not due to a lack of speB expression (Fig. 1). Importantly, results obtained with DNA microarrays and RT-PCR were qualitatively cognate.

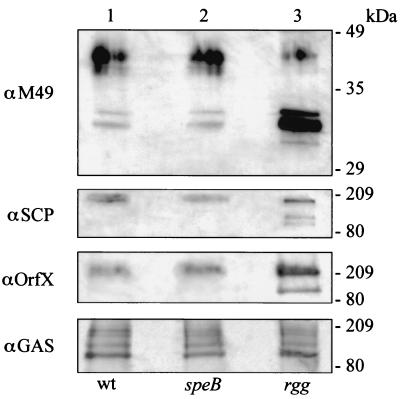

To determine if the observed changes in transcription of the Mga regulon were associated with changes in protein production, immunoblotting was done following whole-cell electrophoresis of wild-type NZ131, speB mutant strain NZ131, and rgg mutant strain NZ131 harvested in the exponential phase of growth (A600 = 0.2). NZ131 speB was analyzed to control for potential degradation of antigens by the SPE B protease. The rgg mutant expressed more M49, C5a peptidase, and OrfX than did the isogenic parental strain and the speB mutant (Fig. 2). Production of M49 was dramatically influenced by rgg inactivation, whereas relatively minor differences in the production of C5a peptidase and OrfX were detected. In addition, faster-migrating species of immunoreactive proteins were repeatedly observed following whole-cell electrophoresis of NZ131 rgg compared to the control strains. The molecular basis for the aberrantly migrating proteins is not known. Equal numbers of CFU of each strain were evaluated, and antisera to the group A streptococcal carbohydrate confirmed that similar amounts of immunoreactive proteins were analyzed (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Increased production of M protein, C5a peptidase (SCP), and OrfX in NZ131 rgg. Production of selected Mga-regulated proteins was assessed by immunoblotting following whole-cell electrophoresis of wild-type (wt) strain NZ131 (lane 1), speB mutant strain NZ131 (lane 2), and rgg mutant strain NZ131 (lane 3). M protein (αM49), C5a peptidase (αSCP), and OrfX (αOrfX) were detected with antisera specific to the polypeptides, as indicated to the left of each panel. The migration and size of the molecular mass standards are shown to the right of each panel. Antisera to the group A streptococcus carbohydrate (αGAS) was used to confirm that similar amounts of cell wall antigens were analyzed. The experiment was repeated twice, and a representative result is shown.

Rgg influences csrRS expression.

Transcripts of mf-1 and sagA were more abundant in the rgg mutant (Table 2), similar to results previously obtained with csrR mutants (14, 17). To determine if the changes in expression of these genes were associated with altered transcription of csrRS, the quantities of csrR, csrS, and CsrRS-regulated gene transcripts were determined in wild-type strain NZ131, speB mutant strain NZ131, and rgg mutant strain NZ131. Transcripts of csrR and csrS were less abundant in the rgg mutant than in both the isogenic wild-type strain and an speB mutant (Table 3). The hasABC gene products catalyze hyaluronic acid biosynthesis (13). Expression of hasAB is increased in csrR mutants (3, 25). Similarly, transcription of hasA and hasB was enhanced in the rgg mutant by 3.3- and 2.3-fold, respectively (Table 3). The hasABC genes are contiguous in the chromosome (11). The hasC gene is located 192 bp downstream of hasB and encodes a UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase that is not required by all strains of S. pyogenes for capsule synthesis (12). In contrast to hasA and hasB, no difference in the quantity of hasC transcripts was detected in the rgg mutant (Table 3). Streptokinase is an activator of human plasminogen, and certain alleles, including ska from strain NZ131, have been associated with poststreptococcal acute glomerulonephritis in a rabbit model (37). DNA microarray analysis of the rgg mutant did not detect a difference in ska transcription (data not shown). However, ska expression is increased in csrR mutants (14). Thus, it was of interest to quantitate ska transcripts in wild-type NZ131, speB mutant strain NZ131, and rgg mutant strain NZ131. In contrast to results obtained with DNA microarrays, ska transcripts were more abundant in the rgg mutant (Table 3). Quantitative RT-PCR confirmed that the expression of mf-1 and sagA is increased in the rgg mutant (Table 3). The results suggest that some of the observed differences in gene transcription in the rgg mutant are due to decreased expression of csrRS.

TABLE 3.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of CsrRS-regulated genes

| SPy no. | Designationb | Quantity of transcripta (mean ± SEM)

|

rgg/wild-type ratioc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type NZ131 | speB mutant NZ131 | rgg mutant NZ131 | |||

| 0336 | csrR (CsrR) | 5.95 ± 0.8 | 7.81 ± 0.6 | 3.62 ± 0.3 | 0.6 |

| 0337 | csrS (CsrS) | 1.15 ± 0.2 | 1.23 ± 0.1 | 0.70 ± 0.0 | 0.6 |

| 0738 | sagA (SLS) | 6.32 ± 0.5 | 6.38 ± 0.5 | 26.63 ± 3.2 | 4.2 |

| 1979 | ska (SKA) | 38.39 ± 3.0 | 47.53 ± 3.9 | 58.35 ± 19.7 | 1.5 |

| 2043 | mf-1 (MF-1) | 1.00 ± 0.1 | 0.92 ± 0.2 | 4.48 ± 0.5 | 4.5 |

| 2200 | hasA (HasA) | 0.12 ± 0.0 | 0.13 ± 0.0 | 0.39 ± 0.3 | 3.3 |

| 2201 | hasB (HasB) | 0.03 ± 0.0 | 0.05 ± 0.0 | 0.07 ± 0.0 | 2.3 |

| 2202 | hasC (HasC) | 0.16 ± 0.0 | 0.18 ± 0.0 | 0.16 ± 0.0 | 1.0 |

The gene-specific cDNA values were normalized to the quantity of gyrA cDNA in each sample. The mean ± the standard error of the mean of two independently isolated RNA samples is given.

Gene designations are in italics, and the corresponding protein designations are in parentheses.

Quantity of gyrA-normalized cDNA in rgg mutant strain NZ131 ÷ quantity in wild-type NZ131.

Confirmation of changes in virulence-associated gene transcription with RT-PCR.

DNA microarray analysis of the rgg mutant detected differences in the transcript levels of several genes known or thought to contribute to virulence (Table 2). Quantitative RT-PCR was used to confirm and quantitate differences in these transcript levels in wild-type strain NZ131, speB mutant strain NZ131, and rgg mutant strain NZ131 (Table 4). Transcripts encoding the potential virulence factors SpeG, Isp-1, and Isp-2 were similarly analyzed. The results confirmed that transcription of mac was increased in NZ131 rgg compared to both the wild-type and speB mutant NZ131 strains (Table 4). However, in contrast to results obtained with DNA microarrays, quantitative RT-PCR showed that grab transcripts were less abundant in the rgg mutant than in the wild-type and speB mutant NZ131 strains (Table 4). Transcription of speH was enhanced in the rgg mutant independently of speB, whereas there was virtually no change in the transcription of speG, which also encodes a superantigen (Table 4). The functions of the extracellular proteins Isp-1 and Isp-2 are not known; however, Isp-2 is expressed during human infection with S. pyogenes and may be involved in host-pathogen interactions (33). isp-1, but not isp-2, transcripts were less abundant in the rgg mutant (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of virulence-associated gene transcripts

| SPy no. | Designationb | Quantity of transcripta (mean ± SEM)

|

rgg/wild-type ratioc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type NZ131 | speB mutant NZ131 | rgg mutant NZ131 | |||

| 0167d | slo(SLO) | 0.09 ± 0.0 | 0.10 ± 0.0 | 1.25 ± 0.1 | 13.9 |

| 0212 | speG (SpeG) | 0.42 ± 0.1 | 0.56 ± 0.0 | 0.33 ± 0.0 | 0.8 |

| 0747 | None (none) | 0.31 ± 0.0 | 0.26 ± 0.0 | 1.00 ± 0.1 | 3.2 |

| 0861 | mac(Mac) | 0.03 ± 0.0 | 0.04 ± 0.0 | 0.06 ± 0.0 | 2.0 |

| 1008 | speH(SpeH) | 0.090 ± 0.0 | 0.11 ± 0.1 | 0.18 ± 0.1 | 2.0 |

| 1357 | grab(Grab) | 1.80 ± 0.2 | 1.71 ± 0.3 | 0.20 ± 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 1436 | mf-3(MF-3) | 0.14 ± 0.0 | 0.14 ± 0.0 | 3.47 ± 0.0 | 24.8 |

| 1801 | isp-2 (Isp-2) | 3.91 ± 0.9 | 3.36 ± 0.9 | 3.63 ± 0.8 | 0.9 |

| 2025 | isp-1(Isp-1) | 1.07 ± 0.3 | 0.63 ± 0.1 | 0.46 ± 0.1 | 0.4 |

The gene-specific cDNA values were normalized to the quantity of gyrA cDNA in each sample. The mean ± the standard error of the mean of two independently isolated RNA samples is given.

Gene designations are in italics, and the corresponding protein designations are in parentheses.

Quantity of gyrA-normalized cDNA in rgg mutant NZ131 ÷ quantity in wild-type NZ131.

Boldface denotes differences in transcripts between wild-type NZ131 and rgg mutant NZ131 of less than 0.5 or greater than 1.5.

MF-1 is a secreted nuclease (49). Expression of a second putative extracellular nuclease, designated MF-3, was previously discovered to be up-regulated in NZ131 rgg in the stationary phase of growth (10). Quantitative RT-PCR confirmed that transcription of mf-3 and a gene encoding a protein with homology to nuclease H (SPy0747) was increased in the rgg mutant (Table 4).

Rgg influences expression of several regulatory genes.

Inactivation of rgg altered expression of four previously characterized regulatory loci (mga, csrR, csrS, and sagA). To identify additional changes in regulatory gene expression, the transcript levels of genes encoding two-component regulators were determined. We focused on two-component regulatory systems because they are important regulators of virulence factor expression in many pathogenic bacteria. FasABC is a three-component system involved in the regulation of fibronectin- and fibrinogen-binding and streptokinase activity (20). Transcription of fasABC was decreased by approximately 50% for each gene (Table 5), consistent with the previous finding that transcription of fasABC is polycistronic (20). Additional two-component regulatory genes that were differentially expressed included spy0875, cpsX, yufM, lytR, ihk, and irr (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of selected regulatory gene transcripts

| SPy no. | Designationb | Quantity of transcripta (mean ± SEM)

|

rgg/wild-type ratioc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type NZ131 | speB mutant NZ131 | rgg mutant NZ131 | |||

| 0242d | fasB(FasB) | 0.50 ± 0.1 | 0.55 ± 0.0 | 0.23 ± 0.0 | 0.5 |

| 0244 | fasC(FasC) | 0.69 ± 0.1 | 0.68 ± 0.1 | 0.28 ± 0.0 | 0.4 |

| 0245 | fasA(FasA) | 0.28 ± 0.0 | 0.29 ± 0.0 | 0.15 ± 0.0 | 0.5 |

| 0528 | sycF (SycF) | 1.74 ± 0.2 | 3.55 ± 0.1 | 2.08 ± 0.0 | 1.2 |

| 0529 | sycG (SycG) | 1.36 ± 0.2 | 1.65 ± 0.1 | 1.31 ± 0.2 | 1.0 |

| 0874 | trcR (TrcR)ef | 1.21 ± 0.2 | 1.36 ± 0.0 | 1.70 ± 0.2 | 1.4 |

| 0875 | None (none) | 1.25 ± 0.0 | 1.31 ± 0.2 | 2.28 ± 0.6 | 1.8 |

| 0895 | cpsX(CpsX) | 0.92 ± 0.1 | 1.16 ± 0.1 | 1.80 ± 0.2 | 2.0 |

| 0898 | cpsY (CpsY) | 0.34 ± 0.0 | 0.33 ± 0.0 | 0.35 ± 0.0 | 1.0 |

| 1061 | yesN (YesN) | 0.67 ± 0.1 | 0.46 ± 0.0 | 0.59 ± 0.2 | 0.9 |

| 1062 | yesM (YesM) | 0.39 ± 0.0 | 0.34 ± 0.1 | 0.34 ± 0.0 | 0.9 |

| 1106 | yufM(YufM)eg | 0.28 ± 0.1 | 0.39 ± 0.0 | 0.53 ± 0.0 | 1.9 |

| 1236 | ciaS (CiaS)eh | 1.33 ± 0.4 | 1.49 ± 0.4 | 1.15 ± 0.2 | 0.9 |

| 1237 | ciaR (CiaR)eh | 0.73 ± 0.2 | 0.92 ± 0.1 | 0.81 ± 0.2 | 1.1 |

| 1556 | zmpS (ZmpS)eh | 0.48 ± 0.1 | 0.44 ± 0.1 | 0.55 ± 0.1 | 1.1 |

| 1587 | lytR(LytR)ei | 0.21 ± 0.0 | 0.15 ± 0.0 | 0.41 ± 0.1 | 2.0 |

| 1588 | lytS (LytS)ei | 13.4 ± 2.2 | 21.7 ± 7.9 | 16.0 ± 0.9 | 1.2 |

| 1908 | salR (SalR)ej | 0.58 ± 0.0 | 0.57 ± 0.1 | 0.58 ± 0.19 | 1.0 |

| 1909 | salK (SalK)ej | 2.95 ± 0.5 | 3.35 ± 0.1 | 2.92 ± 0.6 | 1.0 |

| 2026 | ihk(Ihk) | 1.23 ± 0.2 | 1.18 ± 0.1 | 0.69 ± 0.0 | 0.6 |

| 2027 | irr(Irr) | 0.71 ± 0.2 | 0.64 ± 0.1 | 0.33 ± 0.0 | 0.5 |

The gene-specific cDNA values were normalized to the quantity of gyrA cDNA in each sample. The mean ± the standard error of the mean of two independently isolated RNA samples is given.

Gene designations are in italics, and the corresponding protein designation are in parentheses.

Quantity of gyrA-normalized cDNA in rgg mutant NZ131 ÷ quantity in wild-type NZ131.

Boldface denotes differences in transcripts between wild-type NZ131 and rgg mutant NZ131 of less than 0.5 or greater than 1.5.

Designation based on homology with a similar gene in indicated bacterium.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Bacillus subtilis.

Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Staphylococcus aureus.

Streptococcus salivarius.

DISCUSSION

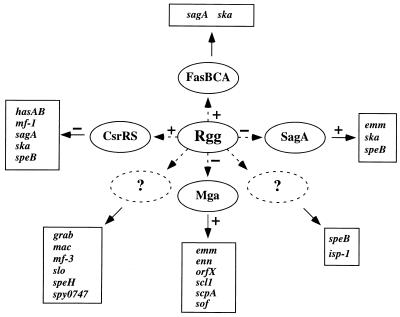

Rgg was initially identified in S. pyogenes as a regulatory protein required for the expression of speB (6, 30). A recent analysis of culture supernatant proteins showed that Rgg influenced the expression of several additional exoproteins (10). The lack of a conserved regulatory motif in the promoter regions of Rgg-regulated genes and the functional diversity of the gene products indicated that Rgg may influence gene expression indirectly by altering expression of additional regulatory loci. Consistent with this hypothesis, we discovered genomewide differences in transcription in the rgg mutant. Differences of 1.5-fold or greater were selected for further study. The biological significance of small differences in transcript levels is likely to vary; however, at least some differences of less than twofold are known to be biologically significant (18). All differentially expressed virulence-associated genes identified by DNA microarrays were further analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. With the exception of grab, the results were qualitatively similar. Transcripts of several previously described regulatory genes, including csrRS, fasBCA, mga, and sagA, were altered in the rgg mutant. In addition, transcript levels of several uncharacterized two-component regulators such as ihk, irr, lytR, spy0875, cpsX, and yufM were altered. The changes in transcription of regulatory genes were accompanied by changes in expression of known or putative virulence factors, including emm, scpA, scl1, hasAB, slo, sagA, ska, speH, grab, mac, mf-1, and mf-3. The results demonstrate that Rgg is an important regulatory factor that interacts with several regulatory networks to coordinate virulence-associated gene expression in S. pyogenes (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Influence of Rgg with other regulatory networks. Positive regulation and negative regulation of gene expression are designated by plus and minus signs, respectively. Dashed arrows indicate possible indirect influences on gene expression. Dashed ovals represent putative regulatory intermediates.

Transcription of rgg is elevated in NZ131 speB compared to that in the isogenic wild-type strain (10). The observation indicated that the lack of speB expression in the rgg mutant could influence gene expression independently of Rgg. To control for this possibility, the quantities of selected gene transcripts were determined in wild-type strain NZ131, speB mutant strain NZ131, and rgg mutant strain NZ131 (Fig. 1; Tables 3 to 5). Levels of transcripts of emm49, enn, scpA49, and orfX were slightly higher in the speB mutant than in the wild-type strain; however, an increase in the corresponding proteins was not apparent (Fig. 2). In general, the quantities of Rgg-regulated gene transcripts were similar in the wild-type and isogenic speB mutant strains. Thus, the observed differences in gene transcription in the rgg mutant are associated with inactivation of the rgg locus and not with the absence of speB expression.

Rgg differentially regulates expression of SPE B and M protein.

Rgg represses transcription of mga and Mga-regulated genes (Fig. 1). As previously noted, mga expression is autoregulated, which implies that a repressor limits transcription (34). Deletion of the region of the chromosome containing the distal mga promoter (designated Mga binding site I) increased transcription of mga via the P1 promoter, suggesting that the putative repressor was interacting with cis elements contained in the deleted region (34). Our results suggest that Rgg may be the repressor detected by McIver et al. (34). However, it remains to be determined if Rgg acts directly or indirectly to repress mga expression.

The discovery that Rgg positively influences speB expression and represses emm49 expression contributes to the idea that the genes encode proteins with contrary functions. Mga and Mga-regulated genes are maximally expressed in the exponential phase of growth (32). The phenotype of exponential-phase S. pyogenes is postulated to be associated with adherence and resistance to the host immune response (7). In contrast, SPE B is produced primarily in the stationary phase of growth, which has been suggested to represent a nonadherent-invasiveness phenotype (9, 19). Moreover, the SPE B protease can degrade cell-associated adhesins, including M49, and abrogate interactions (adherence and internalization) of S. pyogenes with cultured mammalian cells (2, 7). We speculate that Rgg coordinates the transition between adherent and disseminating phenotypes by repressing genes associated with adherence and activating genes associated with dissemination. Clearly, additional information is needed regarding genomewide transcript profiles of S. pyogenes in different stages of growth.

Rgg influences expression of additional regulatory networks.

The two-component regulator CsrRS was initially discovered as a repressor of the hyaluronic acid biosynthesis genes hasAB (3, 25). The DNA binding site of CsrR in the hasA promoter region has been identified (3), which indicates that CsrR directly regulates expression of capsule biosynthesis genes. Phosphorylated CsrR also interacts with the promoter regions of speB, sagA, mf-1, and ska, indicating that CsrR directly represses expression of these genes (36). Transcription of csrR and csrS was decreased in an rgg mutant (Table 3), which was associated with increased levels of transcripts of hasAB, ska, sagA, and mf-1. Together, the results suggest that increased transcription of hasAB, ska, sagA, and mf-1 in the rgg mutant is due to decreased transcription of crsRS. The cellular concentration of CsrR is important in determining the interaction of CsrR with promoter regions (36). Thus, a decrease in csrR expression could significantly affect the regulatory activity of CsrR (36). Decreased transcription of csrR in the rgg mutant was not associated with increased transcription of speB, indicating that speB expression may require direct activation by Rgg. Nonetheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that Rgg acts directly to influence the expression of hasAB, sagA, mf-1, and ska. Similarly, increased expression of speB in csrR mutants may be associated with increased expression of rgg.

The quantities of 23 gene transcripts associated with 12 two-component regulatory systems were determined in wild-type strain NZ131, speB mutant strain NZ131, and rgg mutant strain NZ131 (Table 5). Transcripts of 11 loci were altered by at least 0.5- or 1.5-fold in the rgg mutant compared to those in the isogenic parental strain NZ131 and the speB mutant. Although the majority of two-component regulatory systems have not been characterized in S. pyogenes, the changes in transcription are likely to contribute to the pleiotropic phenotype of the rgg mutant.

Initial characterization of NZ131 rgg did not identify a general defect in the secretion apparatus of the mutant (6). Consistent with this, no significant changes in hemolytic activity, DNase activity, and streptokinase activity were observed in the mutant compared to those in the wild-type strain (6). Similar results were reported for an rgg (ropB) mutant of S. pyogenes strain HSC5 (30). The previous results differ with the findings of the present study, which showed elevated transcripts of genes encoding known and putative extracellular nucleases (mf-1, mf-3, and spy0747), hemolysins (slo and sagA), and ska in rgg mutant strain NZ131. In addition, the nuclease MF-1 and the putative nuclease MF-3 were more abundant in culture supernatant proteins from stationary-phase rgg mutant strain NZ131 cultures than in those from the control strain (10). Several explanations may account for these discrepancies. In the present study, transcript levels were determined at a single time point early in the exponential phase of growth. In contrast, the plate assays previously used to assess changes in hemolytic, nuclease, and streptokinase activities represented the accumulation of exoproteins throughout the exponential and stationary phases of growth. In addition, production of the SPE B protease in the wild-type strains may have diminished protein activity in plate assays. Future studies aimed at determining the influence of rgg inactivation on transcription during additional growth stages and under different culture conditions are clearly important.

To summarize, inactivation of rgg has genomewide effects on virulence-associated gene transcription. Many of the changes are likely the result of changes in the expression of known and putative regulatory loci. Further genome scale analyses of additional regulatory gene mutants are likely to reveal similar interactions among regulatory networks. Such analysis will result in a better understanding of how bacteria coordinate gene expression and may lead to new strategies for the control of virulence by inhibiting global regulators of virulence-associated genes.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Cleary, J. Dale, and B. Lei for providing antiserum, J. R. Fitzgerald, B. J. Hinnebusch, and N. P. Hoe for critical review of the manuscript, and the University of Oklahoma Genome Center for release of serotype M1 genome sequence data prior to completion of the project.

Editor: E. I. Tuomanen

REFERENCES

- 1.Beckert, S., B. Kreikemeyer, and A. Podbielski. 2001. Group A streptococcal rofA gene is involved in the control of several virulence genes and eukaryotic cell attachment and internalization. Infect. Immun. 69:534-537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berge, A., and L. Björck. 1995. Streptococcal cysteine proteinase releases biologically active fragments of streptococcal surface proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 270:9862-9867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernish, B., and I. van de Rijn. 1999. Characterization of a two-component system in Streptococcus pyogenes which is involved in regulation of hyaluronic acid production. J. Biol. Chem. 274:4786-4793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Betschel, S. D., S. M. Borgia, N. L. Barg, D. E. Low, and J. C. S. De Azavedo. 1998. Reduced virulence of group A streptococcal Tn 916 mutants that do not produce streptolysin S. Infect. Immun. 66:1671-1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caparon, M. G., and J. R. Scott. 1987. Identification of a gene that regulates expression of M protein, the major virulence determinant of group A streptococci. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:8677-8681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaussee, M. S., D. Ajdic, and J. J. Ferretti. 1999. The rgg gene of Streptococcus pyogenes NZ131 positively influences extracellular SPE B production. Infect. Immun. 67:1715-1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaussee, M. S., R. L. Cole, and J. P. M. van Putten. 2000. Streptococcal erythrogenic toxin B abrogates fibronectin-dependent internalization of Streptococcus pyogenes by cultured mammalian cells. Infect. Immun. 68:3226-3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaussee, M. S., D. Gerlach, C.-E. Yu, and J. J. Ferretti. 1993. Inactivation of the streptococcal erythrogenic toxin B gene (speB) in Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 61:3719-3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaussee, M. S., E. R. Phillips, and J. J. Ferretti. 1997. Temporal production of streptococcal erythrogenic toxin B (streptococcal cysteine proteinase) in response to nutrient depletion. Infect. Immun. 65:1956-1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaussee, M. S., R. O. Watson, J. C. Smoot, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Identification of Rgg-regulated exoproteins of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 69:822-831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crater, D. L., and I. van de Rijn. 1995. Hyaluronic acid synthesis operon (has) expression in group A streptococci. J. Biol. Chem. 270:18452-18458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeAngelis, P. L., J. Papaconstantinou, and P. H. Weigel. 1993. Isolation of a Streptococcus pyogenes gene locus that directs hyaluronan biosynthesis in acapsular mutants and in heterologous bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 268:14568-14571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dougherty, B. A., and I. van de Rijn. 1992. Molecular characterization of a locus required for hyaluronic acid capsule production in group A streptococci. J. Exp. Med. 175:1291-1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Federle, M. J., K. S. McIver, and J. R. Scott. 1999. A response regulator that represses transcription of several virulence operons in the group A streptococcus. J. Bacteriol. 181:3649-3657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferretti, J. J., W. M. McShan, D. Ajdic, D. J. Savic, G. Savic, K. Lyon, C. Primeaux, S. Sezate, A. N. Suvorov, S. Kenton, H. S. Lai, S. P. Lin, Y. Qian, H. G. Jia, F. Z. Najar, Q. Ren, H. Zhu, L. Song, J. White, X. Yuan, S. W. Clifton, B. A. Roe, and R. McLaughlin. 2001. Complete genome sequence of an M1 strain of Streptococcus pyogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4658-4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fogg, G. C., C. M. Gibson, and M. G. Caparon. 1994. The identification of rofA, a positive-acting regulatory component of prtF expression: use of an mγδbased shuttle mutagenesis strategy in Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 11:671-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heath, A., V. J. DiRita, N. L. Barg, and N. C. Engleberg. 1999. A two-component regulatory system, CsrR-CsrS, represses expression of three Streptococcus pyogenes virulence factors, hyaluronic acid capsule, streptolysin S, and pyrogenic exotoxin B. Infect. Immun. 67:5298-5305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes, T. R., M. J. Marton, A. R. Jones, C. J. Roberts, R. Stoughton, C. D. Armour, H. A. Bennett, E. Coffey, H. Dai, Y. D. He, M. J. Kidd, A. M. King, M. R. Meyer, D. Slade, P. Y. Lum, S. B. Stepaniants, D. D. Shoemaker, D. Gachotte, K. Chakraburtty, J. Simon, M. Bard, and S. H. Friend. 2000. Functional discovery via a compendium of expression profiles. Cell 102:109-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kapur, V., S. Topouzis, M. W. Majesky, L.-L. Li, M. R. Hamrick, R. J. Hamill, J. M. Patti, and J. M. Musser. 1993. A conserved Streptococcus pyogenes extracellular cysteine protease cleaves human fibronectin and degrades vitronectin. Microb. Pathog. 15:327-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kreikemeyer, B., M. D. P. Boyle, B. A. Buttaro, M. Heinemann, and A. Podbielski. 2001. Group A streptococcal growth phase-associated virulence factor regulation by a novel operon (Fas) with homologies to two-component-type regulators requires a small RNA molecule. Mol. Microbiol. 39:392-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuo, C. F., J. J. Wu, K. Y. Lin, P. J. Tsai, S. C. Lee, Y. T. Jin, H. Y. Lei, and Y. S. Lin. 1998. Role of streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin B in the mouse model of group A streptococcal infection. Infect. Immun. 66:3931-3935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.La Penta, D., X. P. Zhang, and P. P. Cleary. 1994. Streptococcus pyogenes type IIa IgG Fc receptor expression is co-ordinately regulated with M protein and streptococcal C5a peptidase. Mol. Microbiol. 12:873-879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lara-Tejero, M., and J. E. Galán. 2000. A bacterial toxin that controls cell cycle progression as a deoxyribonuclease I-like protein. Science 290:354-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lei, B., F. R. DeLeo, N. P. Hoe, M. R. Graham, S. M. Mackie, R. L. Cole, M. Liu, H. R. Hill, D. E. Low, M. J. Federle, J. R. Scott, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Evasion of human innate and acquired immunity by a bacterial homologue of CD11b that inhibits opsonophagocytosis. Nat. Med. 7:1298-1305. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Levin, J. C., and M. R. Wessels. 1998. Identification of csrR/csrS, a genetic locus that regulates hyaluronic acid capsule synthesis in group A streptococcus. Mol. Microbiol. 30:209-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, Z., D. D. Sledjeski, B. Kreikemeyer, A. Podbielski, and M. D. P. Boyle. 1999. Identification of pel, a Streptococcus pyogenes locus that affects both surface and secreted proteins. J. Bacteriol. 181:6019-6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lukomski, S., C. A. Montgomery, J. Rurangirwa, R. S. Geske, J. P. Barrish, G. J. Adams, and J. M. Musser. 1999. Extracellular cysteine protease produced by Streptococcus pyogenes participates in the pathogenesis of invasive skin infection and dissemination in mice. Infect. Immun. 67:1779-1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lukomski, S., K. Nakashima, I. Abdi, V. J. Cipriano, R. M. Ireland, S. D. Reid, G. G. Adams, and J. M. Musser. 2000. Identification and characterization of the scl gene encoding a group A streptococcus extracellular protein virulence factor with similarity to human collagen. Infect. Immun. 68:6542-6553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lukomski, S., S. Sreevatsan, C. Amberg, W. Reichardt, M. Woischnik, A. Podbielski, and J. M. Musser. 1997. Inactivation of Streptococcus pyogenes extracellular cysteine protease significantly decreases mouse lethality of serotype M3 and M49 strains. J. Clin. Investig. 99:2574-2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lyon, W. R., C. M. Gibson, and M. G. Caparon. 1998. A role for trigger factor and an Rgg-like regulator in the transcription, secretion and processing of the cysteine proteinase of Streptococcus pyogenes. EMBO J. 17:6263-6275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McIver, K. S., A. S. Heath, B. D. Green, and J. R. Scott. 1995. Specific binding of the activator Mga to promoter sequences of the emm and scpA genes in the group A streptococcus. J. Bacteriol. 177:6619-6624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McIver, K. S., and J. R. Scott. 1997. Role of mga in growth phase regulation of virulence genes of the group A streptococcus. J. Bacteriol. 179:5178-5187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McIver, K. S., S. Subbarao, E. M. Kellner, A. S. Heath, and J. R. Scott. 1996. Identification of isp, a locus encoding an immunogenic secreted protein conserved among group A streptococci. Infect. Immun. 64:2548-2555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McIver, K. S., A. S. Thurman, and J. R. Scott. 1999. Regulation of mga transcription in the group A streptococcus: specific binding of Mga within its own promoter and evidence for a negative regulator. J. Bacteriol. 181:5373-5383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLandsborough, L. A., and P. P. Cleary. 1995. Insertional inactivation of virR in Streptococcus pyogenes M49 demonstrates that VirR functions as a positive regulator of ScpA, FcRA, OF, and M protein. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 128:45-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller, A. A., N. C. Engleberg, and V. J. DiRita. 2001. Repression of virulence genes by phosphorylation-dependent oligomerization of CsrR at target promoters in S. pyogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 40:976-990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nordstrand, A., W. M. McShan, J. J. Ferretti, S. E. Holm, and M. Norgren. 2000. Allele substitution of the streptokinase gene reduces the nephritogenic capacity of group A streptococcal strain NZ131. Infect. Immun. 68:1019-1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Podbielski, A., A. Flosdorff, and J. Weber-Heynemann. 1995. The group A streptococcal virR49 gene controls expression of four structural vir regulon genes. Infect. Immun. 63:9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Podbielski, A., and B. A. B. Leonard. 1998. The group A streptococcal dipeptide permease (Dpp) is involved in the uptake of essential amino acids and affects the expression of cysteine protease. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1323-1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Podbielski, A., B. Pohl, M. Woischnik, C. Körner, K.-H. Schmidt, E. Rozdzinski, and B. A. B. Leonard. 1996. Molecular characterization of group A streptococcal (GAS) oligopeptide permease (Opp) and its effect on cysteine protease production. Mol. Microbiol. 21:1087-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Podbielski, A., M. Woischnik, B. A. Leonard, and K. H. Schmidt. 1999. Characterization of nra, a global negative regulator gene in group A streptococci. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1051-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Podbielski, A., M. Woischnik, B. Pohl, and K. H. Schmidt. 1996. What is the size of the group A streptococcal vir regulon? The Mga regulator affects expression of secreted and surface virulence factors. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 185:171-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Proft, T., S. L. Moffatt, C. J. Berkahn, and J. D. Fraser. 1999. Identification and characterization of novel superantigens from Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Exp. Med. 189:89-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rakonjac, J. V., J. C. Robbins, and V. A. Fischetti. 1995. DNA sequence of the serum opacity factor of group A streptococci: identification of a fibronectin-binding repeat domain. Infect. Immun. 63:622-631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rasmussen, M., A. Edén, and L. Björck. 2000. SclA, a novel collagen-likesurface protein of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 68:6370-6377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rasmussen, M., H.-P. Müller, and L. Björck. 1999. Protein GRAB of Streptococcus pyogenes regulates proteolysis at the bacterial surface by binding α2-macroglobulin. J. Biol. Chem. 274:15336-15344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simpson, W. J., D. LaPenta, C. Chen, and P. P. Cleary. 1990. Coregulation of type 12 M protein and streptococcal C5a peptidase genes in group A streptococci: evidence for a virulence regulon controlled by the virR locus. J. Bacteriol. 172:696-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smoot, L. M., J. C. Smoot, M. R. Graham, G. A. Somerville, D. E. Sturdevant, C. A. Lux-Migliaccio, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Global differential gene expression in response to growth temperature alteration in group A streptococcus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:10416-10421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sriskandan, S., M. Unnikrishnan, T. Krausz, and J. Cohen. 2000. Mitogenic factor (MF) is the major DNase of serotype M89 Streptococcus pyogenes. Microbiology 146:2785-2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]