Abstract

Streptococcus gordonii is a primary etiological agent in the development of subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE), producing thrombus formation and tissue damage on the surfaces of heart valves. This is ironic, considering its normal role as a benign inhabitant of the oral microflora. However, strain FSS2 of S. gordonii has been found to produce several extracellular aminopeptidase- and fibrinogen-degrading activities during growth in a pH-controlled batch culture. In this report, we describe the purification, characterization, and partial cloning of a predicted serine class arginine aminopeptidase (RAP) with some cysteine class characteristics. Isolation of this enzyme by anion-exchange, gel filtration, and isoelectric focusing chromatography yielded a protein monomer of approximately 70 kDa, as shown by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization, gel filtration, and sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under denaturing conditions. Nested-PCR cloning enabled the isolation of a 324-bp-long DNA fragment encoding the 108-amino-acid N terminus of RAP. Culture activity profiles and N-terminal sequence analysis indicated the export of this protein from the cell surface. Homology was found with a putative dipeptidase from Streptococcus pyogenes and nonspecific dipeptidases from Lactobacillus helveticus and Lactococcus lactis. We believe that RAP may serve as a critical factor for arginine acquisition during nutrient stress in vivo and also in the proteolysis of host proteins and peptides during SBE pathology.

Streptococcus gordonii is a frequently researched member of the viridans family of oral streptococci (54). Viridans streptococci are primary colonizers of human dental plaque, where they serve a critical role in the establishment of microbial communities associated with good oral health. Although considered benign inhabitants of the oral microflora, members have been implicated in the systemic disease subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE) (8, 33). The progression of this disease state requires: (i) trauma (congenital or inflammatory) to the endothelial valve surface such that it is predisposed to colonization, (ii) adhesion of organisms to the modified valve surface after their entry into the bloodstream via the oral cavity, and (iii) the propagation of infected vegetations consisting of bacteria in a fibrin-platelet meshwork (51). Despite the uniform susceptibility of these organisms to β-lactam antibiotics and their lack of classical streptococcal virulence factors, they can cause a chronic inflammation and/or life-threatening disease with periods of latency and recalcitrant infection (9, 18).

The ability of these organisms to form biofilm surfaces within two distinct microenvironments evoked studies of their patterns of gene expression and dynamic metabolism. Streptococcus sanguinis, studied as a model for viridans streptococcal pathogenesis, is known to express cell surface adhesins and a platelet aggregation-associated protein (PAAP) that facilitate both colonization and thrombosis (16, 19). Upon their entry into the bloodstream, bacteria undergo a shift from mildly acidic pH (6.0 to 6.5) in dental plaque to neutral pH (7.3) in the blood (43). This is significant, since among proteins extracted from Streptococcus oralis grown in batch culture and analyzed by two-dimensional electrophoresis, 39 showed altered expression at pH 5.2 versus 7.0 (55). Indeed, in vivo expression technology used on the S. gordonii rabbit model for infective endocarditis to detect genes activated in the new environment indicated an up-regulation of the msrA oxidative stress gene (53) and the induction of genes encoding carbohydrate metabolism enzymes, protein transporters, and cell surface proteins (26). The expression and secretion of glycosidase and peptidase activities, as examined in pH-controlled batch cultures, was found to be down-regulated by acid growth conditions and up-regulated by growth in a neutral pH environment supplemented with serum (17).

Survival in vivo is dependent on the ability of the bacterium to remove sufficient quantities of nutrients from its environment. It is presumed that S. gordonii meets these needs by degrading salivary carbohydrates and glycoproteins in the oral cavity and utilizing plasma proteins when growing on heart valve surfaces. The free concentration of arginine in dental plaque has been measured in trace amounts (<1 μM) during periods of fasting, while meals present higher, variable levels (14). The amino acid constitutes 8% (by mass) of human fibrinogen, serving as a constant, plentiful reservoir. The vegetation biofilm is known to retard the diffusion of antibiotics (24), and solutes generally diffuse into the interior at lower rates than in water (50). Thus, access to carbohydrates and plasma proteins within the vegetation remains problematic. Under such conditions, where carbohydrates are scarce, oral streptococci can catabolize arginine via the arginine deiminase (ADI) pathway, resulting in the synthesis of both ATP and other essential metabolic precursors (7, 14). The utilization of the amino acid is then prioritized, so the transport and metabolism of arginine-containing peptides may become particularly important. The amino acid and peptide transport systems of viridans streptococci have been described previously (2, 5, 10, 25, 31), and it has been shown that amino acids and small peptides are readily imported while those exceeding size limitations require hydrolysis by endo- and exopeptidases either present on the surface or secreted by these cells (6). One such activity that could meet the transport and metabolic challenges in vivo is an arginine aminopeptidase. Such an enzyme has been described in cell wall and cytoplasmic preparations of Streptococcus mitis and S. sanguinis (1, 12, 21) but has eluded detailed investigations. Here, we describe the purification, characterization, and partial cloning of the first reported extracellular arginine aminopeptidase (RAP) derived from S. gordonii FSS2, a strain previously isolated from the bloodstream of an SBE patient (37).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

H-Gly-Pro-p-nitroanalide (H-Gly-Pro-pNa), H-Gly-Arg-pNa, H-Gly-pNa, Ile-Pro-Arg-pNa, l-Leu-pNa, Lys-Arg-pNa, l-Pro-pNa, Sar-Pro-Arg-pNa, di-isopropyl fluorophosphate (DFP), Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine-chloromethyl ketone, iodoacetamide, O-phenanthroline, amastatin, apstatin, bestatin, β-mercaptoethanol, l-cysteine, l-arginine, l-lysine, Gly-Pro, Gly-Gly, angiotensin III, fibronectin binding inhibitor, platelet aggregation inhibitor, sexual agglutination peptide, substance P, thymopentin fragment, bradykinin, lymphocyte-activating pentapeptide fragment, and fibrin polymerization inhibitor were obtained from Sigma. Pefabloc SC, 3,4-dichloroisocoumarin, and E-64 were from Boehringer Mannheim. Anistatin-related peptide, benzoyl (Bz)-Arg-pNa, H-Arg-pNa, H-Ala-pNa, H-Ile-pNa, H-Lys-pNa, H-Val-pNa, and protein kinase C substrate were from Bachem. Protein kinase C peptide was purchased from American Peptide Company, and H-Glu-(NHO-Bz) pyrollidide was from Calbiochem. α1 proteinase inhibitor and α-2 macroglobulin were purchased from Athens Research and Technology, Athens, Ga.

Bacterial growth.

S. gordonii FSS2 (previously S. sanguinis FSS2 [17, 37]) was stored and maintained (at −80°C) as previously described (39). Frozen cells were inoculated into autoclaved medium containing 20 g of trypticase peptone (BBL)/liter, 5 g of yeast extract (Difco)/liter, 2 g of NaCl/liter, 0.1 g of CaCl2/liter, 4 g of K2HPO4/liter, and 1 g of KH2PO4/liter. Ten grams of glucose per liter and 0.5 g of l-arginine/liter were filter sterilized and subsequently added. A static culture (200 ml) was grown overnight at 37°C, and a 15-liter batch culture was further inoculated and grown in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% N2 at 37°C with the pH held constant at 7.0 by addition of 5 M KOH. Cultures were harvested in early stationary phase at a point when the bacteria had metabolized all available glucose and the addition of base was no longer required.

Enzymatic assay.

Amidolytic activities of crude samples and purified protease were measured using the substrate H-Arg-pNa (final concentration, 1 mM) in buffer A (50 mM Tris, 1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.8) at 37°C. Assays were performed on 96-well plates (0.1 ml) using a temperature-controlled microplate reader, and the release of p-nitroaniline was measured at 405 nm (Spectramax; Molecular Devices). Inhibition assays involved preincubation of pure enzyme with inhibitor for 10 min at 37°C, followed by measurement of residual activity.

Enzyme purification.

Four liters of cell-free culture filtrate was obtained after centrifugation (20 min; 4°C at 6,000 × g) of the batch culture. Proteins in the filtrate were precipitated with the addition of (NH4)2SO4 over several hours at 4°C to a final concentration of 80%, and the precipitate was pelleted by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 40 min. The pellets were resuspended in 30 ml of buffer A and dialyzed over 2 days (4°C) with two buffer changes, each against 40 volumes of the same buffer. The dialyzed material was applied to a DE52 (Whatman) column (2.5 by 30 cm; 150 ml) equilibrated with buffer A, which was then washed with 3 column volumes of buffer A at 1 ml/min. All protein that eluted in the flowthrough was pooled and concentrated by ultrafiltration. The concentrated sample (10 ml) was loaded onto and eluted from a Superdex-75 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) HR 10/30 column equilibrated with gel filtration buffer (50 mM Tris, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.02% sodium azide, pH 7.8) and eluted with the same buffer at 1 ml/min. Peak activities were combined and concentrated. The sample (10 ml) was then applied to a Mono Q HR 10/10 fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with equilibration buffer until the baseline stabilized, a linear gradient (0 to 500 mM NaCl in buffer A) was applied, and peak enzyme activity was eluted between 200 and 250 mM NaCl. After pooling and concentration of the active fractions, protein was dialyzed against 25 mM N-methyl piperazine, pH 5.3, and loaded onto a Mono-P 10/5 FPLC chromatofocusing column equilibrated with the same buffer. The column was then washed with 4 column volumes of equilibration buffer, and a pH gradient was developed with 40 ml of 10×-diluted Polybuffer 74 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) adjusted to a pH of 3.8. Peak activity was pooled and concentrated to a volume of 2.0 ml.

Protein determination.

The protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid reagent kit (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Electrophoresis.

Enzyme purity was determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using a 10% acrylamide gel and the Tris-HCl-Tricine buffer system, according to the method of Schagger and von Jagow (47). For amino-terminal sequence analysis, RAP was resolved by SDS-PAGE, followed by electroblotting to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane using 10 mM 3-(cyclohexylamino) propanesulfonic acid-10% methanol, pH 11 (38). The blot was air dried and subjected to sequencing.

Enzyme kinetics and specificity.

Kinetic values were measured using H-Arg-pNa and other substrates at various concentrations (25 μM to 2 mM), with a fixed enzyme concentration of 34 nM, in 100 mM Tris, pH 7.8, at 37°C. Vmax and Km values were obtained through hyperbolic regression analysis (shareware from J. S. Easterby, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, United Kingdom).

Specificity studies utilized RAP incubated with 5 μg of peptide in a 1:1,000 (enzyme/substrate) molar ratio. Reactions were done in 100-μl volumes with 100 mM Tris, pH 7.8, at 37°C for 2 h. Digestions were terminated by acidification with 10 μl of 10 M HCl, followed by centrifugation (10,000 × g; 5 min.). The entire supernatant was applied to reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography using an LC-18 column (25 by 4.6 mm; 5-μm particle size) (Supelco) equilibrated with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in high-pressure liquid chromatography grade water and developed with an acetonitrile gradient (0 to 80% in 0.08% trifluoroacetic acid over 50 min). The peaks were manually collected and analyzed by mass spectrometry.

Mass spectrometry.

Peptides and native RAP were analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) on a Hewlett-Packard G2030A mass spectrometer. The instrument was operated at an accelerating voltage of 28 kV, an extractor voltage of 7 kV, and a pressure of 7 × 10−7 torr. Samples were dissolved in sinapanic acid and ionized from the probe tip using a nitrogen laser source. Calibration was performed using mixtures of peptides and proteins of known molecular masses.

Internal sequencing.

Proteins and peptides were sequenced by Edman degradation in a Procise-cLC sequencer (PE Biosytems, Foster City, Calif.) operated using the manufacturer's protocol. To obtain internal sequences, proteins were in-gel digested with trypsin (sequence grade; Promega), the peptides were extracted (46), and their masses were determined by reflectron MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry using a Bruker Daltonics ProFlex instrument (44). The selected peptides were sequenced by Edman degradation.

Cloning of DNA fragment encoding N-terminal region of RAP.

DNA from S. gordonii was purified using the Purgene DNA isolation kit (Gentra, Minneapolis, Minn.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The internal peptide sequence (DLTADGSTLFGR) was used to search the unfinished S. gordonii database available at The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) (ftp://ftp.tigr.org/pub/data/s_gordonii/). Briefly, DNA sequences were imported into Microsoft Word and searched for a matching DNA sequence encoding the peptide, using wild cards at degenerate code positions. One matching contig was found that contained a DNA sequence encoding the N terminus and internal fragment of RAP. Subsequently, two PCR primers (5"-AGAGGATCCATGAAGAAAATACTGCTC-3" and 5"-GAAGGATCCGTTACTTCCG TTGTCAC-3") were synthesized and used in the PCR to obtain a DNA fragment encoding the N-terminal fragment of RAP. PCR was performed using the Pwo DNA polymerase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.), 1 μg of S. gordonii DNA, and 500 ng of the primers (94°C for 1 min, 65°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min; 32 cycles). A single 340-bp PCR product was obtained, gel purified, digested with BamHI, subcloned into the BamHI site of pUC19, and sequenced.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The obtained sequence was deposited in GenBank under accession number AY052829.

RESULTS

Growth and culture activity.

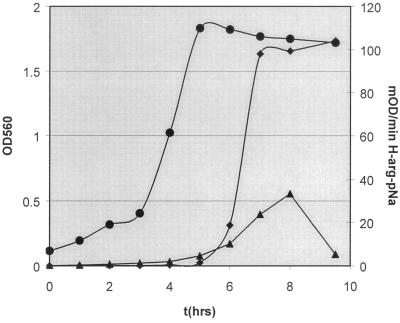

Preliminary experiments indicated the presence of an extracellular H-Arg-pNa activity in culture media. Detection of this amidolytic activity in cell-free filtrate was observed during growth in culture supplemented with 50 mM glucose and 3.5 mM arginine and was dependent on a pH maintained in the range of 6.0 to 7.0. Growth and activity from a 1-liter pH-controlled (pH 7.0) batch culture were monitored at hourly intervals (Fig. 1). Detection of extracellular and cell-associated H-Arg-pNa activity did not occur until early stationary phase, when the bacteria had metabolized all available glucose and the addition of base had ceased. A substantial increase in activity occurred between hours 6 and 7, when extracellular activity increased 5-fold while cell-associated activity had a slight increase of 1.5-fold. Examination of cultures in stationary phase revealed a constant level of H-Arg-pNa activity released into the medium, whereas activity on cell surfaces peaked (approximately one-third of the activity found in medium) at 8 h and fell to basal (pre-stationary-phase) levels at the final time point. The latter phenomenon may be the result of the complete export of H-Arg-pNa activity from the cell surface.

FIG. 1.

S. gordonii FSS2 growth and activity curve from a pH 7.0 controlled culture supplemented with 50 mM glucose and 3.5 mM arginine. Samples (1 ml) were removed from culture at fixed time points, and cells were removed from the medium by centrifugation (5 min; 4°C; 13,000 × g) followed by two washes and resuspension in the initial volume of unsupplemented medium. •, culture turbidity; ⧫, cell-free culture fluid; ▴, washed cells. Assays were performed as previously described using 30 μl of sample. OD560, optical density at 560 nm; t, time.

Enzyme purification.

Maximum activity for the purpose of isolation was achieved using a 4-liter batch culture held at pH 7.0 with added base and harvested during early stationary growth. An 80% ammonium sulfate precipitation concentrated extracellular proteins to a workable volume despite the large decrease in enzymatic yield. A negative DE52 anion-exchange step then permitted an almost twofold increase in RAP activity. The removal of excess arginine (a competitive inhibitor) from the sample and/or an undefined inhibitor of enzymatic activity most likely resulted in this recovery. S-75 gel filtration aided primarily in the removal of high- and low-molecular-weight contaminants, medium pigmentation, and peptide-amino acid components. Mono-Q chromatography provided sufficient anionic affinity for RAP binding to allow for a sixfold increase in specific activity after desorption. The final step, which utilized a Mono-P chromatofocusing column, resulted in a single, defined peak of purified protein, with the concentrated enzyme corresponding to a specific activity of 1,835 U/mg of protein, a greater-than-3,500-fold purification and roughly a 3% yield from the starting batch culture (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Purification of S. gordonii RAP

| Step | Vol (ml) | Total activity (U)a | Total protein (mg) | Sp act (U/mg) | Fold purification | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture filtrate | 3,900 | 8,375 | 15,990 | 0.524 | 1 | 100 |

| Ammonium sulfate precipitation | 43 | 1,707 | 433 | 3.94 | 7.52 | 20 |

| DE52 anion exchange | 10 | 3,284 | 176 | 18.7 | 36 | 40 |

| Superdex 75 | 10 | 1,941 | 8 | 241.3 | 461 | 23 |

| Mono-Q; FPLC | 1 | 449 | 0.3 | 1,496 | 2,855 | 5.5 |

| Mono-P; FPLC | 2 | 232 | 0.12 | 1,835 | 3,506 | 2.8 |

Based on enzymatic activity using H-Arg-pNa in which 1 U = 1 μmol of pNa released per s.

Physical properties.

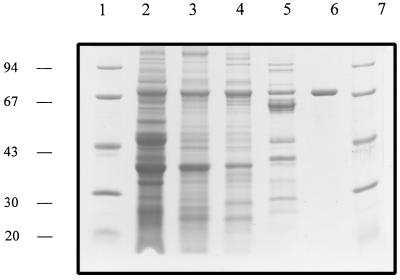

SDS-PAGE analysis of the purified enzyme showed a single protein band, as judged by both Coomassie blue (Fig. 2) and silver (not shown) staining, with an approximate mass of 70 kDa. Analysis of the protein by MALDI-TOF revealed a laser intensity peak that corresponded to a mass of 69,695.6 Da, while analytical Superdex 200 gel filtration indicated a molecular mass of 64 kDa and therefore a monomeric structure. Isoelectric focusing produced a pI of 5.6 for the native protein. The H-Arg-pNa activity was optimum at pH 6.5, with activity detected over a broad phosphate buffer range of 4.0 to 10.0. The enzyme in its pure form was unstable after a 24-h period at either 37 or 25°C, while it was minimally affected at 4°C. However, storage at −20°C over several weeks resulted in a major loss in enzyme, with complete inactivation after a 2-month period.

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE of fractions from the purification of S. gordonii arginine aminopeptidase. Lanes 1 and 7, 15-μg molecular mass markers (phosphorylase b, 94 kDa; bovine serum albumin, 67 kDa; ovalbumin, 43 kDa; carbonic anhydrase, 30 kDa; soybean trypsin inhibitor, 20 kDa). The following lanes contained boiled, reduced samples: lane 2, 120-μg 80% ammonium sulfate precipitation; lane 3, 88 μg of flowthrough from DE52 anion exchange; lane 4, 42-μg peak from Superdex 75 gel filtration wash; lane 5, 34-μg eluted peak from Mono-Q; lane 6, 6 μg of purified RAP (arginine aminopeptidase) from Mono-P.

Enzyme specificity.

Of the 14 chromogenic endo- and aminopeptidase substrates tested on the purified enzyme (Table 2), only H-Arg-pNa was rapidly hydrolyzed. Weaker activity (<10%) was detected against H-Lys-pNa and H-Leu-pNa. When Michaelis-Menten kinetics were measured using H-Arg-pNa as a substrate, a Vmax of 17.44 μmol min−1 and a Km of 51 μM were determined.

TABLE 2.

Relative amidolytic activity of S. gordonii arginine aminopeptidase against various substrates

| Substrate (pNa) | Relative activity (%)a |

|---|---|

| H-Arg | 100 |

| H-Lys | 5 |

| H-Ala | 0 |

| H-Gly | 0 |

| H-Ile | 0 |

| L-Leu | 7 |

| L-Pro | 0 |

| H-Val | 0 |

| H-Gly-Arg | 0 |

| H-Gly-Pro | 0 |

| Lys-Arg | 0 |

| Bz-Arg | 0 |

| Ile-Pro-Arg | 0 |

| Sar-Pro-Arg | 0 |

Activity against H-Arg-pNa hydrolysis was taken as 100.

To obtain further information on cleavage specificity, various peptides (2 to 13 amino acids) were tested as substrates for RAP (Table 3). Significantly, all proteolysis was restricted to peptides with an arginine residue in the N terminus, with cleavage detected only when a hydrophobic or an uncharged residue occupied the second site. There were no apparent additional restrictions for amino acids present downstream of the cleavage site. Extended incubation with peptides failed to yield additional peptide fragments, indicating the absence of endopeptidase activity or contaminating aminopeptidases. The inability of RAP to catalyze endo-specific proteolysis, as tested on whole protein substrates (azocasein, gelatin, collagen type IV, and fibrinogen), further supported the role of the purified enzyme as an exopeptidase.

TABLE 3.

Cleavage specificity of S. gordonii arginine aminopeptidase on peptide substrates

| Substrate | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| Tyrosine kinase substrate | Arg-Arg-Leu-Ile-Glu-Asp-Ala-Glu-Tyr-Ala-Ala-Arg-Gly |

| Anistatin-related peptide | Arg-Cys-Arg-Val-His-Cys-Pro |

| Fibronectin-binding inhibitor | Arg-↓-Gly-Asp-Ser-Pro-Ala-Ser-Ser-Lys-Pro |

| Sexual agglutination peptide | Arg-↓-Gly-Pro-Phe-Pro-Ile |

| Protein kinase C substrate | Arg-↓-Phe-Ala-Arg-Lys-Gly-Ala-Leu-Arg-Gln-Lys-Asn-Val |

| Platelet aggregation inhibitor | Arg-↓-Gly-Glu-Ser |

| Peptide 7 | Arg-↓-Gly |

| Thymopentin fragment | Arg-Lys-Asp-Val-Tyr |

| Peptide 9 | Arg-↓-Phe |

| Substance P | Arg-↓-Pro-Lys-Pro-Gln-Gly-Leu-Met |

| Bradykinin | Arg-↓-Pro-Pro-Gly-Phe-Ser-Pro-Phe-Arg |

| Dipeptide A | Arg-↓-Pro |

| Angiotensin III | Arg-↓-Val-Tyr-Ile-His-Pro-Ile |

| Fibrin polymerization inhibitor (tetrapeptide) | Gly-Pro-Arg-Pro |

| Kallidin | Lys-Arg-Pro-Pro-Gly-Phe-Ser-Pro-Phe-Arg |

| Lymphocyte activating pentapeptide | Leu-Pro-Pro-Ser-Arg |

↓, cleavage site.

Inhibition and activation studies.

Studies with class-specific inhibitors (Table 4) supported the assignment of a serine class mechanism with some cysteine class characteristics. Moderate inhibition was observed using serine protease inhibitors (Pefabloc and, to a lesser extent, DFP and 3,4-dichloroisocoumarin). However, cysteine class inhibitors, iodoacetamide and E-64, had little or no effect on activity, while pCMB, a sulfhydryl-sensitive reagent, was a potent inhibitor of RAP, indicating the possibility of a functional cysteine residue near the vicinity of the active site. Reducing agents (cysteine and β-mercaptoethanol) stimulated activity by approximately 50% and had a more pronounced effect at lower enzyme concentrations. With metallo class inhibitors, 1,10-orthophenanthroline provided no inhibition and EDTA actually stimulated RAP activity in a manner similar to that of the reducing agents. Activity was inhibited by the heavy-metal ions Zn2+ and Co2+ at 1 mM but was increased in the presence of lower-mass mono- and divalent cations. l-Arginine served as a competitive inhibitor, while l-lysine gave minimal inhibition, providing further evidence for strict specificity in the P1 position. Compounds specific for eukaryotic arginine aminopeptidase/aminopeptidase B (EC 3.4.11.6) and leucine aminopeptidase (bestatin), as well as glutamyl aminopeptidase/aminopeptidase A (amastatin), were not inhibitory even at high concentrations. However, RAP was sensitive to the dipeptidyl-peptidase IV (DPP IV)-specific inhibitor H-Glu-pyrollidide and the aminopeptidase P-specific inhibitor apstatin, as evidenced by 98 and 50% inhibition, respectively, at 100 μM. Human plasma inhibitors, α-1-proteinase inhibitor and α-2-macroglobulin, had no effect on enzymatic activity

TABLE 4.

Inhibition profile of S. gordonii arginine aminopeptidase

| Inhibitor | Concn | % Residual activity |

|---|---|---|

| DFP | 5 mM | 75 |

| 10 mM | 56 | |

| Pefabloc | 5 mM | 40 |

| 10 mM | 31 | |

| 3,4-Dichloroisocoumuarin | 2 mM | 62 |

| Amastatin | 1 mM | 89 |

| Bestatin | 1 mM | 68 |

| Apstatin | 100 μM | 50 |

| H-Glu-pyrollidide | 100 μM | 2 |

| E-64 | 500 μM | 98 |

| Iodoacetamide | 5 mM | 91 |

| EDTA | 5 mM | 131 |

| 1,10-Orthophenanthroline | 1 mM | 99 |

| pCMB | 2 mM | 0 |

| l-Cysteine | 5 mM | 148 |

| l-Arginine | 5 mM | 30 |

| l-Lysine | 5 mM | 72 |

| β-Mercaptoethanol | 1 mM | 160 |

| Gly-Gly | 5 mM | 92 |

| Gly-Pro | 5 mM | 104 |

| Na+ | 200 mM | 166 |

| K+ | 5 mM | 131 |

| Ca2+ | 5 mM | 150 |

| Mg2+ | 1 mM | 93 |

| SDS | 5% | 4 |

| Urea | 2 M | 82 |

These results are consistent with previous studies conducted with cell-associated arginine aminopeptidases from S. sanguinis (12) and S. mitis (21).

RAP sequence analysis.

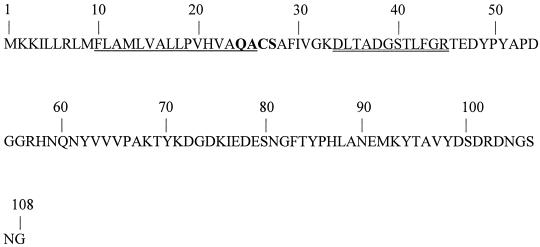

The failure to generate a protein sequence from an apparently blocked N terminus required the sequencing of internal peptides after trypsin digestion. This partial structure resulted in the isolation of a peptide, DLTADGSTLFGR, which was used to design a degenerate primer. In turn, the primer was employed to search the genomic clone of an S. gordonii strain in the Unfinished Microbial Genomes Database of TIGR. A matching contig (bvs 3948) was identified which comprised an incomplete open reading frame of 324 bp and included the internal sequence of RAP. The potential for errors in the electronic sequence necessitated the use of additional cloning methods. N- and C-terminal sequences facilitated the construction of degenerative primers, and PCR against an FSS2 library resulted in the isolation of the 324-bp product that constituted a partial-length DNA fragment. Southern blot analysis was performed with the clone and revealed RAP to be a single-copy gene. A 108-amino-acid polypeptide with a theoretical molecular mass of 11,934 Da and representing approximately 17% of the sequence of the intact protein was encoded by this open reading frame (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

N-terminal sequence of S. gordonii arginine aminopeptidase (RAP) deduced from FSS2 genome. The single-underlined sequence represents the predicted transmembrane domain. The boldface letters mark a conserved signal peptide cleavage site for gram-positive bacteria. The double-underlined sequence represents the internal fragment used to search the electronic database and generate a 340-bp PCR product.

The sequence was analyzed for the presence of gram-positive posttranslational modifications. Predictions indicated an intracellular, positively charged N terminus, a hydrophobic transmembrane domain (H region), and a putative site for signal peptide cleavage (42). This translocation mechanism is well conserved among Bacillus spp. (49) and has been identified in Bacillus subtilis alkaline protease (48) and bacillopeptidase F (56). In RAP, an export signal sequence of 14 hydrophobic residues is located downstream from the N terminus, followed by a polar region (denoted QACS) that provides a cleavage site after alanine.

The finding of an export signal supports the data for extracellular localization in culture experiments. A protein homology search was performed with the 108-amino-acid fragment using CMR BLAST against EMBL, DDBJ, GenBank, and PDB databases. The results indicated that RAP has 65% identity and 82% similarity with the unpublished sequence of a gene encoding an amylase binding protein B (AbpB) from S. gordonii (L. N. Li and F. A. Scannapieco, EMBL AF354648. www.embl.heidelberg.de). RAP and AbpB have predicted transmembrane domains, share nearly identical export signals, and have masses of approximately 70 kDa upon release from the cell. RAP maintains less homology with a putative dipeptidase (TIGR no. NTLO1SPL1617) from Streptococcus pyogenes (44% identity), dipeptidase DA from Lactococcus lactis (34% identity), and nonspecific dipeptidase A from L. helveticus (31% identity).

DISCUSSION

This report describes the purification, characterization, partial cloning, and sequence analysis of an arginine aminopeptidase from S. gordonii FSS2. While this activity has been described in studies concerning arginine proteolysis by S. sanguinis and S. mitis (1, 12, 13, 20, 21, 36), the results presented here are the first biochemical evidence of an extracellular arginine aminopeptidase (RAP) as well as the only study of the molecular structure of a viridans streptococcal arginine aminopeptidase. The enzyme, which was obtained from a pH-controlled culture, was purified over 3,500-fold and was determined to be a homogenous monomeric protein with a molecular mass of 70 kDa. Specificity studies conducted using both p-nitroanilides and peptides smaller than 13 residues indicated only an exopeptidase activity upon incubation with either type of substrate. Although minor Lys and Leu cleavage occurred, efficient aminopeptidase activity required an Arg in the first position, with a nonpolar or uncharged residue preferred in the second site. Inactivation studies propose a serine class catalytic mechanism in which DPPIV- and aminopeptidase P-specific inhibitors appear to be the most effective.

Collectively, the biochemical studies of RAP are consistent with those of arginine aminopeptidases purified from S. mitis ATCC 9811 and S. sanguinis ATCC 903. These enzymes represented the first aminopeptidase B/arginyl-exopeptidase activities isolated from a bacterial source. Previous work had identified two activities, a broad-substrate aminopeptidase and an Arg-specific aminopeptidase, each capable of hydrolyzing arginine-2-naphthylamide when cytoplasmic, cell wall, or membrane fractions were used in cultures undergoing late exponential-early stationary-phase growth (12, 21). These molecular forms differ from each other with respect to their physical properties, inhibition studies, immunochemical properties, and cellular localization. RAP is most closely identified with the Arg-specific, lower-molecular-weight form that is associated with the cell wall and membrane, has been found to be sensitive to heavy metals, and is classified as a cysteine protease based upon inhibition studies. The inhibition of the S. mitis arginine aminopeptidase by pCMB and metals is suggested to be indicative of a sulfhydryl group located near the active site and essential for enzymatic activity (21). Additionally, it was reported that the stimulating effects of reducing agents were evidence for a cysteine residue(s) prone to oxidation (12). However, the sensitivity of RAP to serine class inhibitors, together with general unresponsiveness to cysteine class inhibitors, calls such a characterization into question. The majority of bacterial aminopeptidases, including the broad-substrate Arg-aminopeptidase, are members of the metallo class, and with the exception of the the PepC family, bacterial cysteine class aminopeptidases are a rarity. The elucidation of crystal structures and site-directed mutatgenesis experiments with bacterial prolyl-iminopeptidase (PIP) family members indicated that they are serine peptidases resistant to fluoride compounds, activated by reducing agents, and sensitive to mercurial and heavy-metal salts. These features have made characterization of the enzyme ambiguous and led to their misclassification as cysteine (27). Analysis of PIP genes from Bacillus coagulans (28) and Lactobacillus lactis (29) were modeled upon elucidation of the Xanthomonas campestris three-dimensional structure, a model for the PIP family. The data obtained indicated that the active site was composed of the catalytic triad Asp58, Ser101, and His 267, with Cys62 located at the bottom of the active site about 5 Å from the nucleophilic serine, presumably accounting for its cysteine class behavior (40). However, in the case of RAP, the absence of both a complete sequence and an analogous reactive cysteine provide inconclusive evidence for serine classification.

The pattern of substrate cleavage exhibited by RAP indicates an aminopeptidase with a strict specificity for arginine in the first position and a restriction against a positively charged (Arg or Lys) or polar (Cys) residue in the second. However, proteolysis is favored when a nonpolar or hydrophobic amino acid is present in that position. There is constraint for neither residues downstream of the hydrophobic site nor peptide length, although longer peptides and proteins were not tested.

The unique specificity of RAP for Arg- and Pro-containing substrates may represent a new paradigm for aminopeptidase catalysis. The selectivity of RAP for arginine distinguishes it from eukaryotic aminopeptidase B, which cleaves arginine and lysine from the N terminus equally well (23). Proteolysis with proline in the second position is generally reserved solely for members of the aminopeptidase P family (4). Nevertheless, RAP functioned on three peptides containing Pro in the second position. Furthermore, inhibition was observed with both apstatin and H-Glu-pyrollidide, two compounds that target those peptidases that can accept a Pro in their specificity pockets.

This report provides the initial sequence data for a viridans streptococcal arginine aminopeptidase. A homology search using the partial sequence of RAP revealed significant homology with a group of dipeptidases from gram-positive sources. An unclassified putative dipeptidase from S. pyogenes has the most identity (44% identical; 60% similar) and predicted a protein of about 498 amino acids. It was also suggested to be a cell surface protein with an export signal (VSYACT) similar to that of RAP (VAQACS). Both Lactococcus lactis and L. helveticus express biochemically identical dipeptidases, PepDA (459 amino acids) and cytosol nonspecific dipeptidase EC 3.4.13.18 (474 amino acids), which are approximately 30% identical and 47% similar to RAP (11). These enzymes are biochemically distinct from RAP, are specific for dipeptides of variable composition, and have been isolated from the cytoplasm of prokaryotic cells (34, 35).

Currently, all reported viridans streptococci arginine aminopeptidases have been associated with the cytoplasm, cell wall, or cell membrane (13, 20). The apparent export signal discovered in RAP represents the first extracellular protease from S. gordonii known to follow this secretion mechanism. Similar to other gram-positive exported proteins, RAP maintains N-terminal hydrophobic transmembrane and C-terminal regions in its unprocessed form. The consensus cleavage site (QACS), between residues 24 and 27, most closely resembles those sites in Bacillus sp. proteins. Extracellular proteases from B. subtilis and Lactobacillus lactis (PrsA and PrtM, respectively) maintain SACS sites that are processed via signal peptidase II (32). An oligopeptide-binding protein from S. gordonii also has an analogous AACS site (25).

Although arginine acquisition has been considered an important event inside the cell or in the space between the membrane and cell wall junction during peptide import, studies have not focused on extracellular peptidases capable of generating free arginine either on the cell surface or in the surrounding environment. As opposed to broad-substrate aminopeptidases, the specific arginine aminopeptidase has been implicated in the generation of a substrate for the ADI pathway (22). Suitable concentrations of extracellular arginine are required for proper function of an antiporter that exchanges intracellular ornithine, a metabolite of the ADI pathway, for exogenous arginine (31, 45). The cell surface localization of the highly specific RAP is advantageous for the preservation of an energetically favorable concentration gradient. Its close proximity to the cellular membrane systems involved in amino acid and peptide transport could help meet nutritional requirements. The secretion of RAP would then regulate free arginine concentrations proximal to the cell and serve to scavenge proteins in the local environment, while retention of the broad-substrate aminopeptidase might be necessary for proteolysis of imported peptides and general protein turnover.

In S. gordonii G9B, extracellular protein profiles were altered by changes in pH, medium composition, and rate of growth (30). The secretion of two cytoplasmic proteins from S. gordonii, a GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) (41) and an x-Pro DPP (15), was observed upon growth at a constant, neutral pH. These data are consistent with maximum expression of RAP activity at a controlled pH of 7.0 compared to growth at pH 6.0 and below (data not shown). Growth and activity curves revealed the peak of H-Arg-pNa activity to occur during early stationary phase, when excess glucose had been exhausted and a switch to arginine metabolism was evident by ammonia production in culture. Furthermore, linkage between carbohydrate metabolism and peptide degradation has been established. Experiments showed that the levels of Arg-specific aminopeptidase and the three enzymes of the ADI pathway were suppressed by glucose via catabolite repression in a coordinated manner (22). The slightly alkaline environment of the blood may be more conducive to expression and release of RAP from the cell wall than the more acidic surroundings within plaque. An extracellular RAP may therefore exploit the potential of arginine as an energy source in the protein-rich vegetation versus the carbohydrate-rich oral environment.

Culture supernatant of FSS2 yielded several endopeptidase activities capable of degrading denatured collagen, fibrinogen, and azocasein and at least two additional extracellular aminopeptidases, an x-Pro DPP (15) and Pep V dipeptidase (unpublished data). The concerted action of RAP with these activities would be beneficial for the acquisition of small peptides and exposure of new cleavage sites within the protein meshwork surrounding bacteria in a vegetation. We predict that as a consequence of intense arginine acquisition during physiological stress, RAP may catalyze proteolytic events that could complicate the pathology of SBE. The removal of an N-terminal arginine from bradykinin and substance P produces truncated forms that either have lost essential residues for receptor activation (3) or have been found to display biological activity more potent than that of the intact peptide (57). The combined effect of these modifications could result in local changes in vascular permeability and smooth-muscle contraction at the infected endothelium. The truncation of platelet aggregation inhibitor by RAP could have consequences for thrombus formation and the overall growth of the vegetation. The soluble tetrapeptide RGES, derived from fibrinolysis of the fibrinogen A gamma chain, inhibits both platelet aggregation and fibrinogen binding to activated alpha IIb-beta 3 integrin (52). RAP may inactivate circulating inhibitor in the growing thrombus and alter the balance between polymerization and fibrinolysis in favor of the growing vegetation. Future studies will focus on the expression and knockout of RAP in order to evaluate its relative contributions to streptococcal virulence and survival at the site of infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants DE-09761 and HL 26148 from the NIH.

We thank TIGR for utilization of the unfinished database.

Editor: E. I. Tuomanen

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson, C., L. E. Linder, M. L. Sund, and H. Lonnies. 1992. Purification and characterization of an aminopeptidase from Streptococcus mitis ATCC 903. Curr. Microbiol. 25:261-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson, C., M. L. Sund, and L. Linder. 1984. Peptide utilization by oral streptococci. Infect. Immun. 43:555-560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhoola, K. D., C. D. Figueroa, and K. Worthy. 1992. Bioregulation of kinins: kallikreins, kininogens, and kininases. Pharmacol. Rev. 44:1-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, K. C., and T. M. Buchanan. 1980. Hydrolases from Neisseria gonorrhoeae. The study of gonocosin, an aminopeptidase-P, a proline iminopeptidase, and an asparaginase. J. Biol. Chem. 255:1704-1710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cowman, R. A., and S. S. Baron. 1990. Influence of hydrophobicity on oligopeptide utilization by oral streptococci. J. Dent. Res. 69:1847-1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowman, R. A., and S. S. Baron. 1997. Pathway for uptake and degradation of X-prolyl tripeptides in Streptococcus mutans VA-29R and Streptococcus sanguis ATCC 10556. J. Dent. Res. 76:1477-1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunin, R., N. Glansdorff, A. Pierard, and V. Stalon. 1986. Biosynthesis and metabolism of arginine in bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 50:314-352. (Erratum, 51:178, 1987.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Douglas, C. W., J. Heath, K. K. Hampton, and F. E. Preston. 1993. Identity of viridans streptococci isolated from cases of infective endocarditis. J. Med. Microbiol. 39:179-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drangsholt, M. T. 1998. A new causal model of dental diseases associated with endocarditis. Ann. Periodontol. 3:184-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Driessen, A. J., B. Poolman, R. Kiewiet, and W. Konings. 1987. Arginine transport in Streptococcus lactis is catalyzed by a cationic exchanger. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:6093-6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dudley, E. G., A. C. Husgen, W. He, and J. L. Steele. 1996. Sequencing, distribution, and inactivation of the dipeptidase A gene (pepDA) from Lactobacillus helveticus CNRZ32. J. Bacteriol. 178:701-704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Floderus, E., L. Linder, and M. Sund. 1990. Characterization of membrane-associated arginine aminopeptidase in Streptococcus sanguis 903. Curr. Microbiol. 21:145-149. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Floderus, E., and L. E. Linder. 1990. Localization of aminopeptidases in Streptococcus sanguis strain 903. Curr. Microbiol. 20:255-260. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Floderus, E., L. E. Linder, and M. L. Sund. 1990. Arginine catabolism by strains of oral streptococci. APMIS 98:1045-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein, J. M., A. Banbula, T. Kordula, J. A. Mayo, and J. Travis. 2001. Novel extracellular x-prolyl dipeptidyl-peptidase (DPP) from Streptococcus gordonii FSS2: an emerging subfamily of viridans streptococcal x-prolyl DPPs. Infect. Immun. 69:5494-5501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong, K., T. Ouyang, and M. C. Herzberg. 1998. A streptococcal adhesion system for salivary pellicle and platelets. Infect. Immun. 66:5388-5392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harty, D. W., J. A. Mayo, S. L. Cook, and N. A. Jacques. 2000. Environmental regulation of glycosidase and peptidase production by Streptococcus gordonii FSS2. Microbiology 146:1923-1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herzberg, M. C. 1996. Platelet-streptococcal interactions in endocarditis. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 7:222-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herzberg, M. C., and M. W. Meyer. 1996. Effects of oral flora on platelets: possible consequences in cardiovascular disease. J. Periodontol. 67:1138-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiraoka, B. Y. 1985. Immunochemical properties and intracellular localization of two molecular forms of arginine aminopeptidase in Streptococcus mitis ATCC 9811. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 841:166-172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hiraoka, B. Y., K. Fukasawa, and M. Harada. 1983. Purification and characterization of two novel arginine aminopeptidases from Streptococcus mitis ATCC 9811. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 94:1201-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hiraoka, B. Y., M. Mogi, K. Fukasawa, and M. Harada. 1986. Coordinate repression of arginine aminopeptidase and three enzymes of the arginine deiminase pathway in Streptococcus mitis. Biochem. Int. 12:881-887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hopsu, V. K., K. K. Makinn, and G. G. Glenner. 1966. Characterization of aminopeptidase B: substrate specificity and affector studies. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 114:567-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishida, H., Y. Ishida, Y. Kurosaka, T. Otani, K. Sato, and H. Kobayashi. 1998. In vitro and in vivo activities of levofloxacin against biofilm-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1641-1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenkinson, H. F., R. A. Baker, and G. W. Tannock. 1996. A binding-lipoprotein-dependent oligopeptide transport system in Streptococcus gordonii essential for uptake of hexa- and heptapeptides. J. Bacteriol. 178:68-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kili, A. O., M. C. Herzberg, M. W. Meyer, X. Zhao, and L. Tao. 1999. Streptococcal reporter gene-fusion vector for identification of in vivo expressed genes. Plasmid 42:67-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitazono, A., K. Ito, and T. Yoshimoto. 1994. Prolyl aminopeptidase is not a sulfhydryl enzyme: identification of the active serine residue by site-directed mutagenesis. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 116:943-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitazono, A., T. Yoshimoto, and D. Tsuru. 1992. Cloning, sequencing, and high expression of the proline iminopeptidase gene from Bacillus coagulans. J. Bacteriol. 174:7919-7925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein, J. R., U. Schmidt, and R. Plapp. 1994. Cloning, heterologous expression, and sequencing of a novel proline iminopeptidase gene, pepI, from Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis DSM 7290. Microbiology 140:1133-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knox, K. W., L. N. Hardy, L. J. Markevics, J. D. Evans, and A. J. Wicken. 1985. Comparative studies on the effect of growth conditions on adhesion, hydrophobicity, and extracellular protein profile of Streptococcus sanguis G9B. Infect. Immun. 50:545-554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konings, W. N., B. Poolman, and A. J. Driessen. 1989. Bioenergetics and solute transport in lactococci. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 16:419-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kontinen, V. P., P. Saris, and M. Sarvas. 1991. A gene (prsA) of Bacillus subtilis involved in a novel, late stage of protein export. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1273-1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korzenioswki, O. M., and D. Kaye. 1992. Infective endocarditis, p. 1078-1105. In E. Braunwald (ed.), Heart disease, 4th ed. Saunders, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 34.Kunze, N., H. Kleinkauf, and K. Bauer. 1986. Characterization of two carnosine-degrading enzymes from rat brain. Partial purification and characterization of a carnosinase and a beta-alanyl-arginine hydrolase. Eur. J. Biochem. 160:605-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lenney, J. F., S. C. Peppers, C. M. Kucera-Orallo, and R. P. George. 1985. Characterization of human tissue carnosinase. Biochem. J. 228:653-660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linder, L. E., H. Lonnies, and M. L. Sund. 1996. Analysis of sodium dodecyl sulfate-stable cell wall aminopeptidases in strains of viridans streptococci. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 143:19-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manning, J. E., E. B. Hume, N. Hunter, and K. W. Knox. 1994. An appraisal of the virulence factors associated with streptococcal endocarditis. J. Med. Microbiol. 40:110-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsudaira, P. 1987. Sequence from picomole quantities of proteins electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 262:10035-10038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayo, J. A., H. Zhu, D. W. Harty, and K. W. Knox. 1995. Modulation of glycosidase and protease activities by chemostat growth conditions in an endocarditis strain of Streptococcus sanguis. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 10:342-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Medrano, F. J., J. Alonso, J. L. Garcia, A. Romero, W. Bode, and F. X. Gomis-Ruth. 1998. Structure of proline iminopeptidase from Xanthomonas campestris pv. citri: a prototype for the prolyl oligopeptidase family. EMBO J. 17:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nelson, D., J. M. Goldstein, K. Boatright, D. W. Harty, S. L. Cook, P. J. Hickman, J. Potempa, J. Travis, and J. A. Mayo. 2001. pH-regulated secretion of a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from Streptococcus gordonii FSS2: purification, characterization, and cloning of the gene encoding this enzyme. J. Dent. Res. 80:371-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nielsen, H., J. Engelbrecht, S. Brunak, and G. von Heijne. 1997. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 10:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nolte, W. A. 1982. Defense mechanisms of the mouth, p. 245-260. In W. A. Nolte (ed.), Oral microbiology. C. V. Mosby Company, St. Louis, Mo.

- 44.Pohl, J., F. Hubalek, M. E. Byrnes, K. R. Nielsen, A. Woods, and M. W. Pennington. 1995. Assignment of three disulfide bonds in ShK toxin: a potent potassium channel inhibitor from sea anenome Stichodactyla heliatus. Peptide Sci. 1:291-297. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poolman, B., A. J. Driessen, and W. N. Konings. 1987. Regulation of arginine-ornithine exchange and the arginine deiminase pathway in Streptococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 169:5597-5604. (Erratum, 170:1415, 1988.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Rosenfeld, J., J. Capdevielle, J. C. Guillemot, and P. Ferrara. 1992. In-gel digestion of proteins for internal sequence analysis after one- or two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Anal. Biochem. 203:173-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schagger, H., and G. von Jagow. 1987. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 166:368-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sibakov, M., T. Koivula, A. von Wright, and I. Palva. 1991. Secretion of TEM beta-lactamase with signal sequences isolated from the chromosome of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:341-348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simonen, M., and I. Palva. 1993. Protein secretion in Bacillus species. Microbiol. Rev. 57:109-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stewart, P. S. 1998. A review of experimental measurements of effective diffusive permeabilities and effective diffusion coefficients in biofilms. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 59:261-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sullam, P. M. 1994. Host-pathogen interactions in the development of bacterial endocarditis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 7:304-309. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sultan, C., M. Plantavid, C. Bachelot, P. Grondin, M. Breton, G. Mauco, S. Levy-Toledano, J. P. Caen, and H. Chap. 1991. Involvement of platelet glycoprotein IIb-IIIa (alpha IIb-beta 3 integrin) in thrombin-induced synthesis of phosphatidylinositol 3′,4′-bisphosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 266:23554-23557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vriesema, A. J., J. Dankert, and S. A. Zaat. 2000. A shift from oral to blood pH is a stimulus for adaptive gene expression of Streptococcus gordonii CH1 and induces protection against oxidative stress and enhanced bacterial growth by expression of msrA. Infect. Immun. 68:1061-1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whiley, R. A., and D. Beighton. 1998. Current classification of the oral streptococci. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 13:195-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilkins, J. C., K. A. Homer, and D. Beighton. 2001. Altered protein expression of Streptococcus oralis cultured at low pH revealed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3396-3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu, X. C., S. Nathoo, A. S. Pang, T. Carne, and S. L. Wong. 1990. Cloning, genetic organization, and characterization of a structural gene encoding bacillopeptidase F from Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 265:6845-6850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yajima, H., and K. Kitagawa. 1973. Studies on peptides. XXXIV. Conventional synthesis of the undecapeptide amide corresponding to the entire amino acid sequence of bovine substance P. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 21:682-683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]