Abstract

The fliA gene of Legionella pneumophila encoding the alternative σ28 factor was inactivated by introducing a kanamycin resistance cassette. Electron microscopy and Western blot analysis revealed that the fliA mutant strain is aflagellate and expresses no flagellin. Reporter gene assays indicated that the flaA promoter is not active in the fliA mutant strain. The fliA mutant strain multiplied less effectively in coculture with amoebae than the wild-type strain and was not able to replicate in coculture with Dictyostelium discoideum.

Legionella pneumophila, a pathogen of humans that causes a severe pneumonia termed Legionnaires' disease, is a ubiquitous microorganism that inhabits freshwater biotopes and man-made water systems. In the environment, this bacterium replicates intracellularly in amoebae and other protozoan host cells (5, 26, 28). Legionella infection occurs after inhalation of aerosolized bacteria. Legionella invades and proliferates in alveolar macrophages of the human lung (25, 26).

In order to evaluate the role of the flagellum in the pathogenesis and ecology of Legionella, we recently mutagenized the flaA gene of L. pneumophila Corby. We demonstrated by coculture analysis that the flagellum of L. pneumophila positively affects establishment of infection by enhancing the capacity to invade (4). In contrast, the intracellular rate of replication seems to be unaffected (4, 17).

The complex flagellum expression and assembly system seems to be coordinately regulated with other virulence-associated traits (2, 3, 6, 24, 26). Therefore, it has been proposed that the flagellum might be a virulence-associated factor in the L. pneumophila infection process. Flagellin is the major subunit of the flagella of L. pneumophila, and it has been shown previously that various L. pneumophila strains and isolates of members of the family Legionellaceae other than L. pneumophila are flagellated (11, 23). Furthermore, we demonstrated that expression of the flaA gene seems to be regulated at the transcriptional level by the alternative σ28 factor FliA (11, 12) and probably by a regulator of the LysR family (14). The L. pneumophila fliA gene was able to restore flagellation and motility of an Escherichia coli fliA mutant, suggesting that the FliA protein of L. pneumophila can bind to the E. coli core RNA polymerase and direct transcription initiation from flagellum-specific promoters (12). Furthermore, we demonstrated that flaA expression is regulated by temperature and is influenced by the growth phase, by amino acids, and by the viscosity and the osmolarity of the medium (13).

Genes belonging to the σ28 family (designated sigD, fliA, and rpoF) are required for expression of motility and chemotaxis genes in several organisms (1, 10, 19, 22, 27). These genes are expressed in a complex transcriptional cascade (8, 9). In this study we generated and characterized an fliA mutant strain of L. pneumophila in order to analyze the effect of the mutation on flagellum expression.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides

L. pneumophila Corby (serogroup 1) (15), flaA mutant strain KH3, and complemented flaA mutant strain CD10 (4) were used in this study. E. coli DH5α was used for propagation of recombinant plasmid DNA. The following vectors were used: pUC18 (Pharmacia LKB, Freiburg, Germany), pBC KS (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany), plasmid pMMB207 (20), and plasmid pBOC20 (21). All of the plasmids and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids and oligodeoxyribonucleotides

| Plasmid or oligonucleotide | Characteristics or sequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pKH23 | pMMB207 3,560-bp HindIII-KpnI fragment containing the p flaA-luxAB fusion | 12 |

| pKH12 | pMMB207 containing the p flaA-lacZ fusion from pKH20 | 13 |

| pKH27 | pUC18 1,028-bp PCR product containing fliA and part of flhF (ylxH) | 12 |

| pCD33 | pBC KS containing the complete fliA gene disrupted by a Kmr cassette | This study |

| pKHfli10 | 2,400-bp SalI-SphI fragment of pCD33 containing the disrupted fliA gene cloned in pBOC20 | This study |

| pfli12 | pBC KS containing the complete fliA gene from pKH27 | This study |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| ylxSalI | 5′-AGCCATAGCGTTATGTCGACT-3′ | This study |

| fli3SpeI | 5′-CACTAGTGATTGATAGTCTCCCTC-3′ | This study |

| fli5SpeI | 5′-CAAGTCAACTAGTTGTACACTC-3′ | This study |

| motSphI | 5′-CAGGCATGCAACGACCATTTCATC-3′ | This study |

| fliU5 | 5′-GGATGTGCAGTTAGATTAC-3′ | 12 |

| fliR5 | 5′-TTTATTCCGGTAATCTTGATC-3′ | 12 |

| Ka5-EcoR5 | 5′-CGTGATATCATCCTTCAACTC-3′ | This study |

| Ka3-Spe1 | 5′-GTCTGACTAGTCGGGAAGATG-3′ | This study |

Construction of an L. pneumophila fliA mutant and a complemented fliA mutant strain

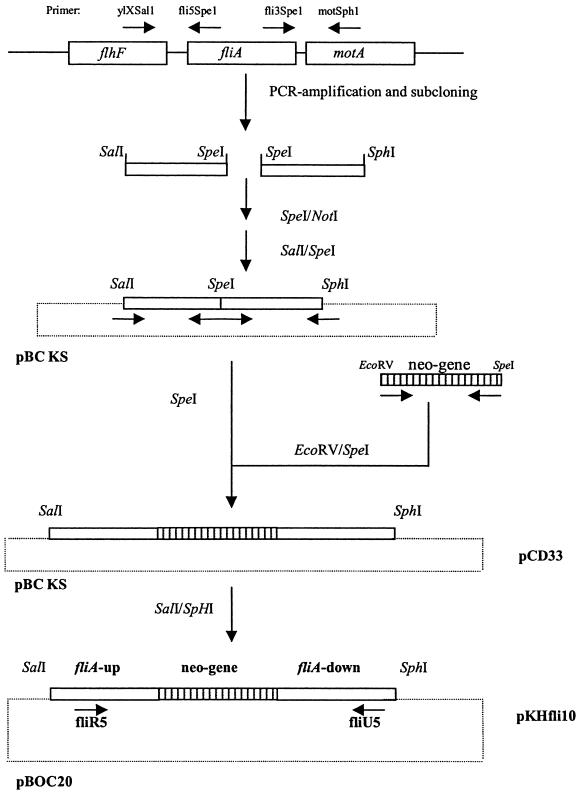

The fliA gene was amplified by PCR, and a kanamycin resistance cassette (neo) was cloned into the SpeI site, which was introduced by PCR (Fig. 1). This construct was then cloned into vector pBOC20, resulting in pKHfli10. This plasmid was used to inactivate the fliA locus of L. pneumophila Corby. We obtained eight putative mutants that grew on ABCYE plates containing kanamycin and sucrose, suggesting that the allelic exchange was due to a double crossover. FliA mutants were screened by PCR performed with primers binding to the 5′ (fliU5) and 3′ (fliR5) regions of the fliA gene (Table 1). Amplification products of the predicted length (1,000 bp) were observed for the wild type, whereas 2,400-bp amplification products (the predicted length) were obtained for the mutant strains, indicating that integration of the 1,400-bp neo gene occurred (data not shown). The recombination event was confirmed by Southern blot analysis using an fliA-specific probe and a neo gene-specific DNA probe (data not shown). Strain KHfli12 was used for complementation and further characterization. Complementation was done by electroporating (2.3 kV, 100 Ω, 25 μF; Bio-Rad Gene Pulser) plasmid pfli12 (Table 1), which contained the complete fliA gene of L. pneumophila Corby cloned into vector pBC KS, into fliA mutant strain KHfli12. Clones growing on ABCYE agar plates supplemented with chloramphenicol were used in the following experiments.

FIG. 1.

Cloning scheme used to inactivate the fliA gene of L. pneumophila Corby. Plasmid designations are indicated on the right, and the vectors used are indicated on the left. The primers used for PCR are indicated by arrows. The restriction endonuclease sites used for cloning are also indicated. neo-gene, kanamycin resistance cassette.

FlaA expression of the fliA mutant strain

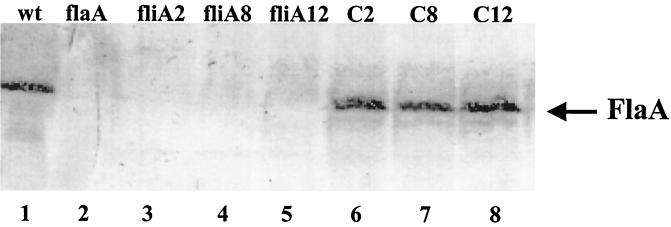

Using an fliA mutant strain of E. coli (YK4104), it was recently shown that, in the recombinant system, expression of the fliA gene depends on the presence of an intact FliA protein (12). To determine whether the fliA mutant strain of L. pneumophila Corby is able to express the flagellin gene, total cell extracts of L. pneumophila strains in the early stationary phase were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting by using a polyclonal monospecific antibody against L. pneumophila Corby flagellin. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed as described by Laemmli (16). Three hundred microliters of a Legionella cell suspension (optical density at 600 nm, 1) was pelleted by centrifugation, and then the cells were suspended in 100 μl of SDS sample lysis buffer and equal amounts of protein were loaded onto an SDS-13% polyacrylamide gel. Western blot analysis revealed that the fliA mutant strain did not express the FliA protein (Fig. 2, lanes 3 to 5), whereas the complemented strain produced a flagellin band (Fig. 2, lanes 6 to 8) comparable to that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 2, lane 1). For electron microscopy, single drops of the Legionella suspension were directly applied to Formvar-coated copper grids. After sedimentation of the bacteria and removal of the remaining fluid, the samples were shadowed with platinum-palladium and examined with a Zeiss 10A transmission electron microscope. The fliA mutant strain had no flagella, whereas the complemented strain was flagellated (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Western blot analysis with the anti-flagellin antibody. Equal amounts of whole-cell extracts were loaded onto the polyacrylamide gel. The position of the FlaA protein (48 kDa) is indicated on the right. Lane 1, L. pneumophila Corby (wild type [wt]); lane 2, flagellin mutant strain KH3 (flaA) of L. pneumophila Corby; lanes 3 to 5, σ28 factor mutant strains fliA2, fliA8, and fliA12 of L. pneumophila Corby; lanes 6 to 8, fliA mutant strains harboring plasmid pfli12 (complemented clones 2 [C2], 3 [C3], and 12 [C12]).

Using plasmid pKH12 (flaA promoter fused to a promoterless lacZ gene; cloning method described by Heuner et al. [13]), we showed that in contrast to the L. pneumophila wild-type strain, the fliA mutant strain exhibited no reporter gene activity (Table 2). Previously, we showed that the σ28 consensus sequence acts as the promoter for flaA expression in L. pneumophila (11). These results, together with the results of the present study, demonstrate that expression of the flagellin gene in L. pneumophila is directly regulated by the alternative σ28 factor FliA. The fliA gene product is also used in transcription of flagellar and chemotaxis genes in various other species (9).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of fliA mutant, complemented mutant, and wild-type strains of L. pneumophila Corby

| Strain | Reaction with anti-FlaA antibodiesa | Flagellationb | flaA promoter activity (β-galacto-sidase activity)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| L. pneumophila Corby | + | + | 434.3 ± 8.1 |

| KHfliA12d | − | − | 11.7 ± 1.8 |

| KHfliA12/ pfli12e | + | + | NDf |

Determined by Western blot analysis of whole-cell extracts of the bacteria.

Determined by electron microscopy.

Values are expressed in Miller units, measured as described by Miller (18).

fliA mutant strain.

Complemented strain.

ND, not determined.

Intracellular multiplication in Acanthamoeba castellanii and Dictyostelium discoideum.

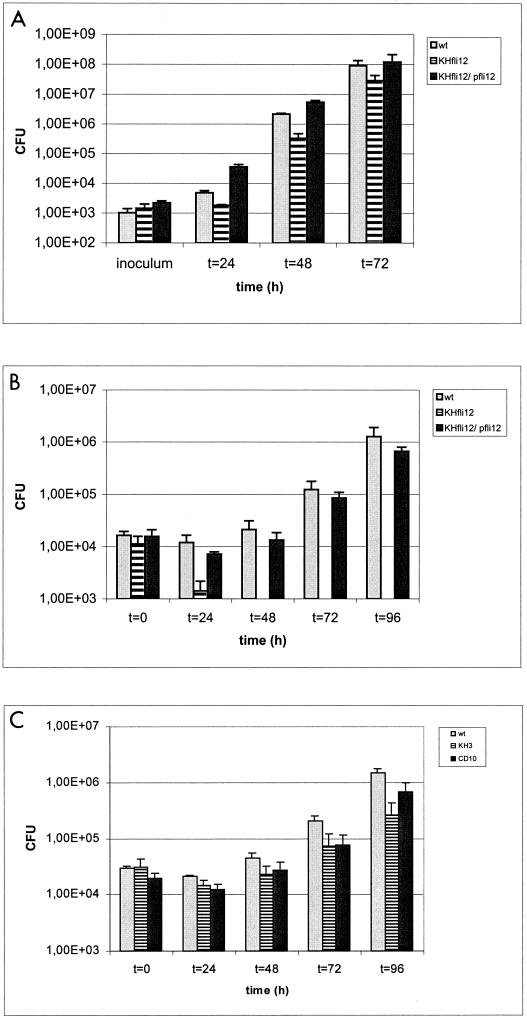

In axenic culture the fliA mutant strain grew as well as the wild-type strain (data not shown). To determine whether disruption of the fliA gene influences intracellular multiplication of the bacteria in host cells, A. castellanii and D. discoideum were infected with the fliA mutant strain or the complemented strain, as described recently (4, 7). The results of the coculture experiments are shown in Fig. 3. The fliA mutant strain multiplied less effectively in coculture with A. castellanii than the wild-type strain (Fig. 3A) and was not able to replicate in D. discoideum (Fig. 3B). The defects were fully complemented by introduction of the wild-type fliA gene back into the fliA mutant strain. Previously, it was demonstrated that the flaA mutant strain had only a moderate effect in coculture with A. castellanii (4). Compared with the fliA mutant strain, the flaA mutant strain had only a minor effect on replication in D. discoideum cultures (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that in addition to the flaA gene, the FliA protein regulates other putative virulence factors of L. pneumophila.

FIG. 3.

Analyses of L. pneumophila Corby (wt), fliA mutant strain fliA12, a complemented fliA mutant strain harboring plasmid pfli12 (KHfli12/pfli12), flaA mutant strain KH3, and complemented flaA mutant strain CD10 in cocultures with A. castellanii (A) or D. discoideum (B and C). A. castellanii cultures (2 × 105 cells/ml) and D. discoideum cultures (5 × 105 cells/ml) were infected with 1 × 103 and 1 × 104 bacteria, respectively. The number of CFU per well was determined in duplicate by plating on ABCYE plates. The error bars indicate the standard deviations based on at least three independent experiments.

Genes involved in flagellum expression are tightly regulated and are organized in a complex hierarchy. In E. coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, there are three levels. The first level of the cascade includes the flhDC operon coding for master regulators, which control class II genes. The class II gene product FliA is required for transcription of class III genes. The last level of the hierarchy includes flagellin genes, as well as genes involved in motility, such as motA and chemotaxis genes (for reviews, see references 8 and 9). To our knowledge, the genomic sequence of L. pneumophila contains no flhDC homologues. Experiments are under way to further analyze this cascade in L. pneumophila in order to identify the proposed master regulator of flagellum expression and to identify additional putative virulence genes regulated by FliA to obtain more information about the link between motility and expression of the virulent phenotype.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joachim Morschhäuser for his careful review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grants DFG 1297/3-10, DFG STE 838/3-1, and GRK 587/1-01; Graduiertenkollegs) and from the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

Editor: S. H. E. Kaufmann

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnosti, D. N., and M. J. Chamberlin. 1989. Secondary sigma factor controls transcription of flagellar and chemotaxis genes in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:830-834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosshardt, S. C., R. F. Benson, and B. S. Fields. 1997. Flagella are a positive predictor for virulence in Legionella. Microb. Pathog. 23:107-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrne, B., and M. S. Swanson. 1998. Expression of Legionella pneumophila virulence traits in response to growth conditions. Infect. Immun. 66:3029-3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dietrich, C., K. Heuner, M. Steinert, and J. Hacker. 2001. Flagellum of Legionella pneumophila positively affects the early phase of infection of eukaryotic host cells. Infect. Immun. 69:2116-2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fields, B. S. 1993. Legionella and protozoa: interaction of a pathogen and its natural host, p. 70-72. In J. M. Barbaree, R. F. Breiman, and A. P. Dufour (ed.), Legionella: current status and emerging perspectives. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 6.Gao, L. Y., O. S. Harb, and Y. Abu Kwaik. 1997. Utilization of similar mechanisms by Legionella pneumophila to parasitize two evolutionarily distant host cells, mammalian macrophages and protozoa. Infect. Immun. 65:4738-4746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hägele, S., R. Kohler, H. Merkert, M. Schleicher, J. Hacker, and M. Steinert. 2000. Dictyostelium discoideum: a new host model system for intracellular pathogens of the genus Legionella. Cell. Microbiol. 2:165-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harshey, R. M., and A. Toguchi. 1996. Spinning tails: homologies among bacterial flagellar systems. Trends Microbiol. 4:226-231. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Helmann, J. D. 1991. Alternative sigma factors and the regulation of flagellar gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 5:2875-2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helmann, J. D., and M. J. Chamberlin. 1987. DNA sequence analysis suggests that expression of flagellar and chemotaxis genes in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium is controlled by an alternative sigma factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:6422-6424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heuner, K., L. Bender-Beck, B. C. Brand, P. C. Lück, K.-H. Mann, R. Marre, M. Ott, and J. Hacker. 1995. Cloning and genetic characterization of the flagellum subunit gene (flaA) of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1. Infect. Immun. 63:2499-2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heuner, K., J. Hacker, and B. C. Brand. 1997. The alternative sigma factor σ28 of Legionella pneumophila restores flagellation and motility to an Escherichia coli fliA mutant. J. Bacteriol. 179:17-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heuner, K., B. C. Brand, and J. Hacker. 1999. The expression of the flagellum of Legionella pneumophila is modulated by different environmental factors. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 175:69-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heuner, K., C. Dietrich, M. Steinert, U. B. Göbel, and J. Hacker. 2000. Cloning and characterization of a Legionella pneumophila specific gene encoding a member of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Mol. Gen. Genet. 264:204-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jepras, R. L., R. B. Fitzgeorge, and A. Baskerville. 1985. A comparison of virulence of two strains of Legionella pneumophila based on experimental aerosol infection of guinea pigs. J. Hyg. Camb. 95:29-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merriam, J. J., R. Mathur, R. Maxfield-Boumil, and R. Isberg. 1997. Analysis of the Legionella pneumophila fliI gene: intracellular growth of defined mutant defective for flagellum biosynthesis. Infect. Immun. 65:2497-2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular biology. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 19.Mirel, D. B., and M. J. Chamberlin. 1989. The Bacillus subtilis flagellin gene (hag) is transcribed by the sigma 28 form of RNA polymerase. J. Bacteriol. 171:3095-3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morales, V. M., A. Baeckmann, and M. Bagdasarian. 1991. A series of wide-host-range low-copy-number vectors that allow direct screening for recombinants. Gene 97:39-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Connell, W. A., E. K. Hickey, and N. P. Cianciotto. 1996. A Legionella pneumophila gene that promotes hemin binding. Infect. Immun. 64:842-848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohnishi, K., K. Kutsukake, H. Suzuki, and T. Iino. 1990. Gene fliA encodes an alternative sigma factor specific for flagellar operons in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Gen. Genet. 221:139-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ott, M., P. Messner, J. Heesemann, R. Marre, and J. Hacker. 1991. Temperature-dependent expression of flagella in Legionella. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:1955-1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pruckler, J. M., R. F. Benson, M. Moyenuddin, W. T. Martin, and B. S. Fields. 1995. Association of flagellum expression and intracellular growth of Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 63:4928-4932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodgers, F. G., and F. C. Gibson. 1993. Opsonin-independent adherence and intracellular development of Legionella pneumophila within U937 cells. Can. J. Microbiol. 39:718-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowbotham, T. J. 1986. Current views on the relationships between amoebae, legionellae and man. Isr. J. Med. Sci. 22:678-689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Starnbach, M. N., and S. Lory. 1992. The fliA (rpoF) gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes an alternative sigma factor required for flagellin synthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 6:459-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinert, M., M. Ott, P. C. Lück, and J. Hacker. 1994. Studies on the uptake and intracellular replication of Legionella pneumophila in protozoa and in macrophage-like cells. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 15:299-308. [Google Scholar]