Abstract

T-cell proliferative responses were studied in two villages in Gabon with different levels of Loa loa transmission. The first village (Okoumbi) had an annual transmission potential (ATP) of ≈9,000 infective larvae (L3)/person/year (high transmission village), while the second village (Ndjokaye) had an ATP of ≈1,000 L3/person/year (low transmission village). Proliferation and cytokine assays were performed on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from individuals aged 18 years and over using either mitogens (concanavalin A or phytohemagglutinin), antigens (purified protein derivative [PPD], irrelevant antigen), or soluble extracts of L3, microfilariae, or adult L. loa. PBMC from individuals in the low transmission village responded better to stimulation with adult antigen and to PPD than did PBMC from individuals in the high transmission village (P = 0.0031 and P = 0.0012, respectively). These data suggest that high levels of transmission of L. loa depress both specific and nonspecific T-cell proliferative responses in infected humans.

Loa loa is a human filarial parasite that infects an estimated 13 million people in equatorial west and central Africa. The disease is characterized by a range of clinical manifestations including Calabar swellings, pruritis, and the ocular passage of the adult worm causing eye inflammation (24). In the endemic population pathologies such as hydrocele in males and encephalopathy are common (4). Other complications, including pulmonary abnormalities, renal disease, and cardiomyopathy, have variously been reported (14, 21). Most immunological studies on L. loa infection have concentrated on analysis of antibody responses (1, 6, 10), with the consequence that our understanding of cellular immune responses is limited (14, 22). In one study carried out in the same area of Gabon as the present study, microfilaremics were reported to display impaired antigen-specific proliferative responses compared to amicrofilaremics (3), a situation similar to that observed in lymphatic filariasis (23, 29). In lymphatic filarial infection, the original studies correlated the proliferative defect with the presence of microfilariae (Mf) (23), but more recent studies have demonstrated that proliferative responses are suppressed in a percentage of all infected or exposed individuals (29). In parallel with defective T-cell proliferative responses, gamma interferon (IFN-γ) levels are significantly reduced in Mf-positive individuals while interleukin-4 (IL-4) levels are similar between different clinical groups (18).

However, the spectrum of infection with L. loa in this area of Gabon is quite different from that usually observed with the lymphatic filarial worms. For L. loa in Gabon, most infected individuals are amicrofilaremic (>70%), while in lymphatic filariasis a significant percentage of infected individuals are usually microfilaremic. Despite this fundamental difference in the parasitological status of infected individuals, there are similarities between the immune response elicited by the lymphatic filariae and by L. loa. For example, immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) levels are elevated during active infection with both lymphatic filarial worms and L. loa, while amicrofilaremic individuals have elevated levels of other parasite-specific IgG subclasses (1, 2, 15).

Studies that have been carried out in other filarial infections with the aim of defining the mechanisms underlying proliferative suppression (17, 25) have shown that no one single factor consistently restores proliferation in vitro. Some studies have shown an antiproliferative effect for IL-10 (17), while a more recent study with Onchocerca volvulus-infected individuals proposed that the proliferative defect is a consequence of the development of Th3 cells secreting the antiproliferative cytokines IL-10 and transforming growth factor β (9). Paradoxically, few studies to date have attempted to investigate the impact of external factors such as levels of transmission on immune responses in filarial infection, and yet herd immunity, which seems to be an important mechanism in human infection, was shown to be dependent upon vector biting rates (20). In this study we present preliminary data on immune regulation in L. loa infection by comparing levels of proliferation and cytokine secretion in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from individuals from two villages in an endemic zone of Gabon that differed only in the intensity of transmission.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Villages and study population

Two villages were designated for entomological follow-up: Okoumbi and Ndjokaye are situated in the forest and savannah areas of Gabon, respectively. Details of the entomological studies are reported elsewhere (J. P. Akue, E. Devaney, G. Wahl, and H. Moukana, submitted for publication). Briefly, Chrysops were captured in these two villages over a period of 1 year and dissected for L. loa infective larvae (L3). The daily biting rate was determined and the annual transmission potential (ATP) was calculated as the daily transmission potential × the percentage of infected Chrysops × the mean number of L3/infected Chrysops. The ATP was defined as the number of L3 potentially infecting an individual per year. Individuals in the two villages donated blood after giving their informed consent and the project was approved by the Ethical Committee of the International Center for Medical Research of Franceville (CIRMF). Blood was collected into EDTA and 1 ml was examined for the presence of Mf by the Knotts technique. The remaining blood was used for isolation of PBMC and plasma.

Parasite materials and antigen preparation.

Adult worms of L. loa were removed by an ophthalmologist during ocular passage. Mf were obtained from heavily infected patients and purified on a Percoll gradient, as previously described (28). L3 were obtained by dissection of naturally infected Chrysops species caught in an L. loa-endemic village. Parasites were stored in liquid nitrogen until required. Adult worms and L3 were washed and then homogenized in RPMI, while Mf were disrupted by sonication in the same buffer. Antigens (Ag) were left to extract on ice for 1 h. The solutions were then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min and sterilized by passage through a 0.2-μm-pore-size filter (Millex; Millipore, Molshein, France). A 20-μl aliquot of Ag solution was removed for protein assay using the Bio-Rad method (5), and the remainder was stored at −70°C until use.

Separation of PBMC

PBMC were separated by Ficoll-Hypaque centrifugation from whole blood diluted 1:1 with RPMI 1640. Cells were then washed twice with RPMI containing 10 μg of gentamicin/ml and cryopreserved in RPMI containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide and 20% human AB serum. For use, cells were thawed and viable cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion. The cells were resuspended to a concentration of 5 × 106 per ml in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 25 mM HEPES buffer, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1% nonessential amino acids, and 10 μg of gentamicin/ml (all from Gibco BRL, Cergy-Pontoise, France) and 10% human AB serum (Centre National de Transfusion Sanguine, Paris, France).

In vitro PBMC proliferation assay

A total of 100 μl of cells previously adjusted to a concentration of 5 × 106 per ml was distributed into the wells of flat-bottomed (mitogen) or round-bottomed (Ag) tissue culture plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). Cells were stimulated with concanavalin A (ConA; 10 μg/ml; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) or phytohemagglutinin (PHA; 10 μg/ml; Sepracor, Villeneuve-la-Garenne, France) as mitogen. For Ag, cells were stimulated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis purified protein derivative (PPD; 10 μg/ml, Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark), the parasite Ag L3 (2 μg/ml), adult worm (5 μg/ml), or Mf Ag (10 μg/ml), or medium alone, exactly as described previously (3). The plates were incubated at 37°C under an atmosphere of 5% CO2-air for 3 days (mitogen) or 5 days (Ag) and then pulsed with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine/well (Amersham, Les Ulis, France). After 16 h, the cells were harvested using a cell harvester and the incorporated counts were measured by scintillation counting. Data are expressed as the mean counts per minute (± the standard error of the mean) of triplicate cultures for Ag- or mitogen-stimulated cultures or medium alone.

Cytokine assays

For cytokine production, supernatants were generated using 5 × 106 cells per ml in 24-well plates with 5 μg of ConA/ml, 10 μg of PHA/ml, 10 μg of L3 Ag/ml, 15 μg of adult Ag/ml, 20 μg of Mf Ag/ml, or medium alone. Culture supernatants were collected at 24 h (mitogens) and 48 h (Ag) for IL-2 and IL-4 determinations and at 96 h (antigens) for measurement of IL-5 and IFN-γ. Cytokine levels were measured by two-site enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay exactly as described previously (3). Results for IL-4 and IL-5 are expressed in picograms per milliliter and results for IL-2 are in units per milliliter, relative to human cytokine standards (R & D Systems, Abingdon, United Kingdom). Levels of IFN-γ were measured using a commercial assay (R & D Systems). The sensitivity of the assays was 0.3 U/ml for IL-2, 10 pg/ml for IL-4 and IL-5, and 7.8 pg/ml for IFN-γ.

Statistical analysis

The Mann-Whitney U test, a nonparametric method, was used to compare median levels of proliferation or cytokines between both villages; the chi-square test was used for comparison of the proportion of males to females in both villages and of the proportion of individuals producing specific cytokines in each village. The Spearman rank correlation test was used to examine the relationship between the density of Mf and the level of proliferation or cytokine production. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant in all cases.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the village and study population.

The details of the ATP calculations have been reported elsewhere (Akue et al., submitted). The village of Okoumbi had an estimated ATP of ≈9,300 L3 per person per year and was defined as a high transmission village, whereas Ndjokaye, with an ATP of ≈1,300 L3 per person per year, was defined as a low transmission village. In the original survey, 111 individuals were examined in Okoumbi (91% of the population) and 73 were examined in Ndjokaye (82% of the population). Similar percentages of the population were microfilaremic in both villages (21% in Okoumbi and 22% in Ndjokaye; P = 0.870). The incidence of reported ocular passage was greater in Okoumbi (43.4%) than in Ndjokaye (15.7%; P = 0.001), while there was no significant difference in the incidence of reported Calabar edema (31.3% in Okoumbi compared to 28.2% in Ndjokaye; P = 0.734).

Blood samples from 37 adults from Okoumbi and 30 adults from Ndjokaye were used for immunological analysis. There was no difference in age or sex of the study populations in the two villages (Table 1). All individuals participating in the study were infected with L. loa, and another filarial parasite, Mansonella perstans, was present in the majority of patients (Table 1). L. loa infection was defined by one or more of the following: presence of L. loa Mf in the blood; elevated levels of IgG4 (greater than the mean plus 1 standard deviation of 11 sera from Gambian individuals infected with M. perstans alone); the ocular passage of an adult worm; or the clinical signs of Calabar edema. Mf levels and levels of L. loa-specific IgG4 tended to be higher in the high transmission village, but these differences did not reach significance. The details of the participating adults are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the villages and the study population

| Village | ATP | No. of subjects (male/female) | Mean age (yr) | No. of Mf+ (range Mf/ml) | No. of Mf− (IgG4 in Mf−)a | M. perstans incidenceb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Okoumbi | 9,300 | 37 (20/17) | 41.7 ± 3.5 | 16 (2-86,000) | 21 (0.744 ± 0.147) | 30/37 |

| Ndjokaye | 1,300 | 30 (12/18) | 42.7 ± 3.9 | 8 (44-5620) | 22 (0.440 ± 0.092) | 28/30 |

MF−, amicrofilaremic but infected based on levels of specific IgG4 greater than mean plus 1 standard deviation of the mean of 11 Gambian subjects infected with M. perstans and/or the ocular passage of an adult worm and/or Calabar edema. IgG4 levels were not significantly different between villages (P = 0.082).

Incidence of M. perstans was not different between groups (P = 0.144).

Proliferation assay.

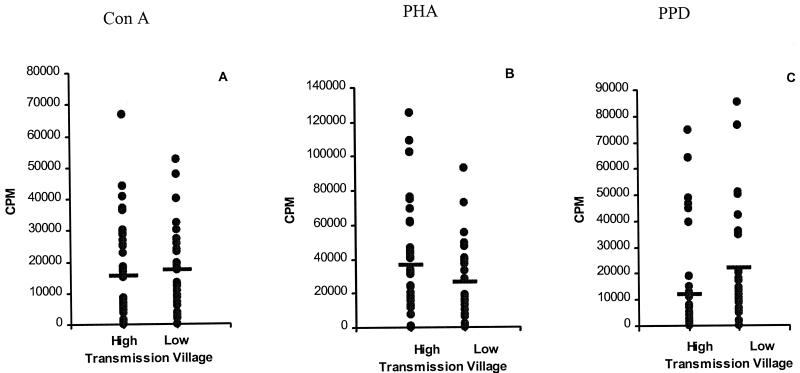

PBMC from the participating patients were used for the proliferation assay in order to compare responses between the two villages. Mitogens (PHA or ConA) and antigens (PPD, L3, Mf, adult Ag) were used to stimulate cells from each individual. Cells from most individuals responded to both mitogens, and there was no significant difference in the counts per minute incorporated by PBMC from individuals in the high or low transmission village in response to ConA (Fig. 1A) or PHA (Fig. 1B). ConA stimulation resulted in a mean counts per minute of 15,559 ± 2,718 in the high transmission village compared to 17,373 ± 2,455 in the low transmission village (P = 0.2538); the corresponding values for PHA were 36,401 ± 5,405 and 26,218 ± 3,983 (P = 0.2591) for the high and low transmission villages, respectively. Interestingly, when proliferative responses to a nonparasite Ag (PPD) were compared between the two villages (Fig. 1C), there was a significant difference, with PBMC from the low transmission village incorporating significantly more counts per minute (21,770 ± 3,941) than PBMC from the high transmission village (11,799 ± 3,233; P = 0.0012).

FIG. 1.

Proliferative response of PBMC from individuals resident in the high and low transmission villages following stimulation with mitogens or nonspecific PPD Ag. Cells were prepared from 37 individuals in the high transmission village and 30 individuals from the low transmission village as described in Materials and Methods and stimulated in triplicate wells with ConA (A), PHA (B), PPD (C), or medium alone. Results show net counts per minute for each individual (counts per minute with stimulation minus counts per minute in medium alone). Horizontal lines denote the mean for each group.

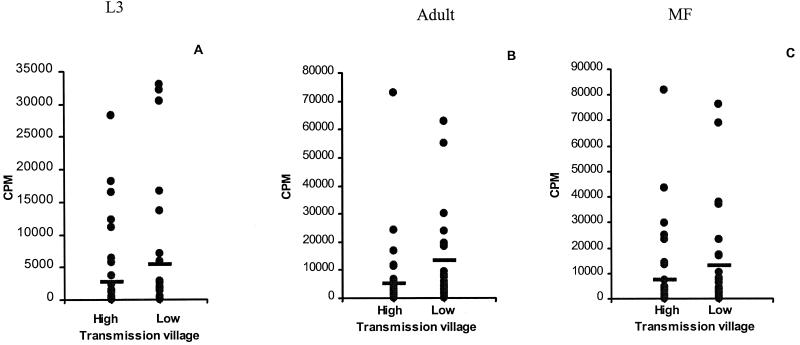

When PBMC were stimulated with adult Loa Ag (Fig. 2B), mean levels of proliferation were significantly higher in the low transmission village (13,312 ± 3,377) than in the high transmission village (5,036 ± 2,071; P = 0.0031). A similar trend was noted with both L3 (Fig. 2A) and Mf (Fig. 2C) Ag, but the differences fell just short of statistical significance (P = 0.0786 and P = 0.0797, respectively). It was notable that levels of spontaneous proliferation were elevated under conditions of high transmission (mean, 1,998 cpm versus 256 cpm in the low transmission village; P = 0.232), and the proportion of individuals having spontaneous counts >1,000 cpm was increased under conditions of high transmission (23 of 37) compared to low transmission (10 of 30; P = 0.019).

FIG. 2.

Proliferative response of PBMC from individuals resident in the high and low transmission villages following stimulation with specific Ag of L. loa. Cells were prepared from 37 individuals in the high transmission village and 30 individuals from the low transmission village as described in Materials and Methods and stimulated in triplicate wells with L3 Ag (A), adult worm (B), or Mf Ag (C). Results show net incorporated counts per minute for each individual. Horizontal lines denote the mean for each group.

Stimulation of PBMC with parasite Ag resulted in a range of reactivity in both villages, with a cluster of individuals responding poorly to Ag and some individuals responding very well (Fig. 2). As previous studies in lymphatic filariasis (23, 29) and in L. loa infection (3) had suggested that proliferative responses were most suppressed in microfilaremic individuals, we compared proliferative responses in microfilaremic and amicrofilaremic individuals in the two villages. As shown in Table 2, in the low transmission village of Ndjokaye, there was no significant difference in proliferative responses to adult Ag between amicrofilaremic and microfilaremic individuals (P = 0.59). In contrast, in the high transmission village, PBMC from amicrofilaremic individuals incorporated significantly more counts per minute than did PBMC from microfilaremics in response to adult Ag (P = 0.0237). Data were also analyzed to investigate other possible correlations: we could find no significant difference in Ag-specific proliferation between individuals with high levels of Mf (>100/ml) and those with low levels of Mf (<100/ml) or any correlation between Mf levels and proliferative capacity in individuals.

TABLE 2.

Proliferative capacity of PBMC from microfilaremics and amicrofilaremics in response to adult Ag and PPD

| Statusa | Proliferative response (cpm)b

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Ag

|

PPD

|

||||

| High | Low | High | Low | ||

| Mf+ | 1,619 ± 804* | 4,787 ± 2,167 | 9,583 ± 5,142** | 32,702 ± 11,414 | |

| Mf− | 7,370 ± 3,375 | 11,932 ± 3,911 | 13,487 ± 4,184*** | 19,086 ± 3,392 | |

Sixteen individuals in the high transmission village were Mf+ and 21 were Mf−. In the low transmission village, 8 individuals were Mf+ and 22 were Mf−.

*, significant difference between Mf+ and Mf− in the high transmission village; P = 0.0237. **, significant difference between Mf+ in the low transmission village and Mf+ in the high transmission village; P = 0.0077. ***, significant difference between Mf− in the low transmission village and Mf− in the high transmission village; P = 0.0437.

When cells were stimulated with PPD, PBMC from microfilaremics in the low transmission village responded better than PBMC from microfilaremics in the high transmission village (P = 0.0077), and the same was also true for PBMC from amicrofilaremics (P = 0.0437) (Table 2). However, there was no significant difference in levels of proliferation between microfilaremics and amicrofilaremics in either village.

Cytokine assays.

In parallel with the proliferation assays, cytokine secretion was also measured in a small subset of individuals from both villages (8 individuals from Ndjokaye and 19 from Okoumbi) in response to in vitro restimulation with adult, Mf, or L3 Ag. The results are summarized in Table 3. There was no significant difference in levels of any cytokine in response to stimulation with L. loa Ag between the high and low transmission villages. However, levels of IL-4, IL-2, and IFN-γ were two to three times greater in the high transmission village than in the low transmission village in response to adult Ag, while levels of IL-5 were similar between villages. With Mf Ag the picture was similar to that observed with adult Ag, with higher levels of both IL-4 and IFN-γ in the high transmission village than in the low transmission village, while levels of IL-2 and IL-5 were similar in both villages. Interestingly, both adult and Mf Ag elicited more IL-4 and IL-5 than did L3 Ag in the high transmission village, and these differences reached statistical significance (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Cytokine levels in PBMC from individuals from the high and low transmission villages in response to stimulation with adult L. loa Agc

| Ag | IL-2 (U/ml)

|

IFN-γ (pg/ml)

|

IL-4 (pg/ml)

|

IL-5 (pg/ml)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | |

| L3 | 0 | 13.9 ± 10.1 | 8.12 ± 5.82 | 67.4 ± 23.2 | 0a | 0a | 65 ± 60.8 | 40.8 ± 17 |

| Adult | 32.5 ± 23.3 | 65 ± 35.8 | 50 ± 25.8 | 121.3 ± 45.8 | 7.5 ± 4.91b | 26.3 ± 10.2 | 616 ± 437 | 802 ± 291 |

| Mf | 112.5 ± 85.4 | 130.5 ± 51.5 | 51.9 ± 28.5 | 138.7 ± 57 | 20 ± 16.7 | 48.4 ± 16.4 | 848 ± 497 | 1,251 ± 466 |

A single individual in each group secreted IL-4 over background levels.

Only three individuals secreted IL-4 at levels above the cutoff (10 pg/ml).

In the high transmission village, IL-4 levels were significantly higher with adult Ag versus L3 (P = 0.0017) and with Mf Ag versus L3 (P = 0.0015); IL-5 levels were significantly higher with adult Ag versus L3 (P = 0.0025) and with Mf Ag versus L3 (P = 0.0008). In the low transmission village, IL-5 levels were significantly higher with Mf Ag versus L3 (P = 0.0101). Sensitivity was 10 pg/ml for IL-4 and IL-5, 7.8 pg/ml for IFN-γ, and 0.3 U/ml for IL-2.

Despite the absence of statistical differences between the villages for any cytokine, it was noted that there were differences between the villages in the number of people who secreted Ag-specific cytokines. For example, in Okoumbi, the high transmission village, a significantly greater proportion of individuals secreted IFN-γ to L3 Ag than in Ndjokaye (χ2 = 10.503; degrees of freedom [df] = 1; P = 0.001). Likewise, an increased proportion of individuals secreted IL-4 in Okoumbi compared to that in Ndjokaye in response to Mf Ag (χ2 = 29.302; df = 1; P = 0.0001) or to adult worm Ag (χ2 =13.52; df = 1; P = 0.0001). Attempts to measure IL-4 and IFN-γ in plasma that had been stored at −20°C were unsuccessful (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The key finding of this study is that the level of transmission of L. loa affects both parasite-specific and nonspecific T-cell proliferative responses in an area of endemicity in Gabon. PBMC from infected individuals from a village with a high level of transmission proliferated significantly less well than PBMC from a low transmission village. This result was most clear-cut when using adult worm Ag, but a similar trend was also noted with Mf and L3 Ag. Previous studies in the same area (3) correlated reduced Ag-specific proliferative responses with the presence of Mf, but in the present study this correlation only held true for the high transmission village when the population was analyzed as microfilaremic or amicrofilaremic. As noted previously, ≈70% of the infected population in this region is amicrofilaremic but infected (as assessed by the ocular passage of an adult worm or elevated Ag-specific IgG4 levels). Despite these results, further analysis of the data did not reveal any correlation between Mf density and proliferative responsiveness at an individual level. Although there was a trend for higher proliferative responses to Ag in both microfilaremics and amicrofilaremics of the low transmission village compared to those in the high transmission village, these differences did not reach statistical significance.

Analysis of ATP in the respective villages revealed that individuals in Okoumbi were exposed annually to seven times the number of L3 compared to those in Ndjokaye. Whether the higher levels of L3 are translated into increased numbers of adult worms remains unclear, as there are no strictly quantitative tests available for measuring adult worm burden. The proportion of individuals who were microfilaremic was similar in both villages, although Mf levels tended to be higher in the high transmission village. Consequently, it is not possible from the available data to definitively state whether the down-regulated proliferative response is driven by continued exposure to high numbers of L3, by the presence of increased numbers of adult worms, or by an increased Mf load in the high transmission village. Differences between the two villages in proliferative responses reached statistical significance only where adult worm Ag was used, not L3 or Mf Ag, although the same trend was apparent with these Ag. These results may suggest that the presence of adult worms is sufficient to suppress proliferative responses but that under conditions of high transmission, Mf also contribute to the down-regulation of proliferative responses. Further studies will be required to clarify this issue. In a recent study on Wuchereria bancrofti infection in Papua New Guinea, it was possible to match patients from low and high transmission villages for adult worm burden on the basis of circulating Ag and Mf levels (13). That study showed that in patients with equivalent worm burdens, proliferative responses and IFN-γ levels were suppressed in individuals from the high transmission village and thus demonstrated that the down-regulated responses under conditions of high transmission were independent of adult worm or Mf burden.

One of the most interesting findings of the present study was that proliferative responses to PPD were also reduced in the high transmission village compared to the low transmission village. In the original studies with lymphatic filariasis, only Ag-specific responses were reported to be affected (23). However, there is a growing recognition that responses to other Ag and in some cases to mitogen may also be impaired, particularly under conditions of high transmission intensity (13). The mechanism by which bystander responses are down-regulated remains unclear, although in W. bancrofti infection high levels of serum IL-4 are correlated with reduced proliferation (13). It may be relevant that the differences in transmission levels were much more profound in the W. bancrofti study (≈63-fold) than in the present study. With O. volvulus, active infection is known to influence the immune response against nonspecific stimuli (11), tetanus vaccine (7, 8), and mycobacterial antigen (27). Modulation of the immune response to irrelevant Ag may in fact be a general phenomenon in helminth infection (19).

While analysis of cytokine responses in a small number of individuals did not reveal any significant differences between the villages, a number of interesting trends were apparent. For example, L3 Ag elicited more IFN-γ and IL-2 in the high transmission village and a significantly greater proportion of individuals secreted IFN-γ to L3 Ag under conditions of intense transmission. In contrast, in vitro restimulation with Ag derived from Mf and adult worms elicited higher levels of IL-4 and IL-5 than did L3 Ag, suggesting that there are differences in the profile of cytokines elicited by specific life cycle stages. Previous studies with Brugia malayi Ag have revealed that Mf and mixed sex adult worm Ag elicited higher levels of IL-10 than adult male Ag (16). In most studies on lymphatic filarial infection, cytokine profiles are dominated by IL-4, IL-10, and IL-5 (for examples, see references 13, 18, and 29), while in L. loa infection the cytokine response appears to be less biased (3). Further studies with larger groups of L. loa-infected individuals will be required to determine whether these findings represent real differences in responses to infection.

In conclusion, our results suggest that the relationship between transmission, cellular immune responses, and the clinical or parasitological outcome of L. loa infection deserves further study. The findings of this and other studies are also of significance for vaccination programs in countries where filarial parasites are endemic (7, 8, 11, 27) and for increased understanding of the interrelationships between immune responses elicited by concurrent infections with different pathogens (12, 26).

Acknowledgments

We thank the population of Okoumbi and Ndjokaye for their constant good will in cooperating with the filariasis research group of CIRMF.

This work was supported by Wellcome Trust grant 047101/2/96/077. CIRMF is sponsored by the State of Gabon, Elf Gabon, and Ministere Francais de la Cooperation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akue, J. P., T. G. Egwang, and E. Devaney. 1994. High levels of parasite-specific IgG4 in the absence of microfilaremia in Loa loa infection. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 45:246-248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akue, J. P., M. Hommel, and E. Devaney. 1997. High levels of parasite-specific IgG1 correlate with the amicrofilaremic state in Loa loa infection. J. Infect. Dis. 175:158-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baize, S., G. Wahl, P. T. Soboslay, T. G. Egwang, and A. J. Georges. 1997. T helper responsiveness in human Loa loa infection: defective specific proliferation and cytokine production by CD4+ T cells from microfilaraemic subjects compared with amicrofilaraemics. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 108:272-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boulestiex, G., and B. Carme. 1986. Encephalite au cours du traitement de la filariose a Loa loa par la diethylcarbamazine. A propos de 6 observations. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exotique 79:649-654. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford, M. 1986. A rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Churchill, D. R., C. Morris, A. Fakoya, S. G. Wright, and R. N. Davidson. 1996. Clinical and laboratory features of patients with loiasis (Loa loa filariasis) in the U.K. J. Infect. 33:103-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper, P. J., I. Espinel, W. Paredes, R. H. Guderian, and T. B. Nutman. 1998. Impaired tetanus-specific cellular and humoral responses following tetanus vaccination in human onchocerciasis: a possible role for interleukin-10. J. Infect. Dis. 178:1133-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper, P. J., I. Espinel, M. Wieseman, W. Paredes, M. Espinel, R. H. Guderian, and T. B. Nutman. 1999. Human onchocerciasis and tetanus vaccination: impact on the post-vaccination anti-tetanus antibody response. Infect. Immun. 67:5951-5957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doetze, A., J. Satoguina, G. Burchard, T. Rau, C. Loliger, B. Fleischer, and A. Hoerauf. 2000. Antigen-specific cellular hyporesponsiveness in a chronic human helminth infection is mediated by T(h)3/T(r)1-type cytokines IL-10 and transforming growth factor-beta but not by a T(h)1 to T(h)2 shift. Int. Immunol. 12:623-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egwang, T. G., A. Dupont, A. Leclerc, J. P. Akue, and M. Pinder. 1989. Differential recognition of Loa loa antigens by sera of human subjects from a loiasis endemic zone. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 41:664-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elkhalifa, M. Y., H. W. Ghalib, T. Dafa'Alla, and J. F. Williams. 1991. Suppression of human lymphocyte responses to specific and non-specific stimuli in human onchocerciasis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 86:433-439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gopinath, R., M. Ostrowski, S. J. Justement, A. S. Fauci, and T. B. Nutman. 2000. Filarial infections increased susceptibility to human immunodeficiency virus infection in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1804-1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King, C. L., M. Connelly, M. A. Alpers, M. Bockarie, and J. W. Kazura. 2001. Transmission intensity determines lymphocyte responsiveness and cytokine bias in human lymphatic filariasis. J. Immunol. 166:7427-7436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klion, A. D., A. Massouwgbodji, B. C. Sadeler, E. A. Ottesen, and T. B. Nutman. 1991. Loasis in endemic and non-endemic populations: immunological mediated differences in clinical presentation. J. Infect. Dis. 163:1318-1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurniawan, A., M. Yazdanbakhsh, V. R. Rees, R. Aalberse, M. E. Selkirk, F. Partono, and R. M. Maizels. 1993. Differential expression of IgE and IgG4 specific antibody responses in asymptomatic and chronic human filariasis. J. Immunol. 150:3941-3950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahanty, S., H. E. Luke, V. Kumaraswami, P. R. Narayanan, V. Vijayshekaran, and T. B. Nutman. 1996. Stage-specific induction of cytokines regulates the immune response in lymphatic filariasis. Exp. Parasitol. 84:282-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahanty, S., and T. B. Nutman. 1995. Immunoregulation in human lymphatic filariasis--the role of interleukin-10. Parasite Immunol. 17:385-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maizels, R. M., E. Sartono, A. Kurniawan, F. Partono, M. E. Selkirk, and M. Yazdanbaksh. 1995. T-cell activation and the balance of antibody isotypes in human lymphatic filariasis. Parasitol. Today 11:50-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malhotra, I., P. Mungai, A. Wamachi, J. Kioko, J. H. Ouma, J. W. Kazura, and C. L. King. 1999. Helminth and Bacillus Calmette-Guerin-induced immunity in children sensitized in utero to filariasis and schistosomiasis. J. Immunol. 162:6843-6848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michael, E., and D. A. P. Bundy. 1998. Herd immunity to filarial infection is a function of vector biting rate. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 26:855-860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nutman, T. B., K. D. Miller, M. Mulligan, and E. A. Ottesen. 1986. Loa loa infection in temporary residents of endemic regions: recognition of a hyperresponsive syndrome with characteristic clinical manifestations. J. Infect. Dis. 15:410-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nutman, T. B., W. Reese, R. W. Poindexter, and E. A. Ottesen. 1988. Immunologic correlates of the hyperresponsive syndrome of loiasis. J. Infect. Dis. 157:544-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ottesen, E. A., P. F. Weller, and L. Heck. 1977. Specific cellular immune unresponsiveness in human filariasis. Immunology 33:413-421. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinder, M., A. Dupont, and T. G. Egwang. 1988. Identification of a surface antigen on Loa loa microfilariae, the recognition of which correlates with the microfilariae in microfilaremic state in man. J. Immunol. 141:2480-2486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sartono, E., Y. C. M. Kruize, F. Partono, A. Kurniawan, R. M. Maizels, and M. Yazdanbakhsh. 1995. Specific T cell unresponsiveness in human filariasis: Diversity in underlying mechanisms. Parasite Immunol. 17:587-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sentogo, E., T. Rubaale, D. W. Buttner, and N. W. Brattig. 1998. T cell responses in coinfection with Onchocerca volvulus and the human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Parasite Immunol. 20:431-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart, G. R., M. Boussinesq, T. Coulson, L. Elson, T. B. Nutman, and J. E. Bradley. 1999. Onchocerciasis modulates the immune response to mycobacterial antigens. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 117:517-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Hoegaerden, M., and B. Ivanoff. 1986. A rapid, simple method for isolation of viable microfilariae. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 35:148-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yazdanbakhsh, M., W. A. Paxton, Y. C. M. Kruize, E. Sartono, A. Kurniawan, A. van het Wout, M. E. Selkirk, F. Partono, and R. M. Maizels. 1993. T cell responsiveness correlates differentially with antibody isotype levels in clinical and asymptomatic filariasis. J. Infect. Dis. 167:925-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]