Abstract

Listeriolysin O (LLO), a cholesterol-binding cytolysin of Listeria monocytogenes, exhibits cytokine-inducing and cytolytic activities. Because the cytolytic activity was abolished by cholesterol treatment but the cytokine-inducing activity was not, these activities appeared to be linked to different domains of the LLO molecule. In this study, we constructed recombinant full-length LLO (rLLO529) and various truncated derivatives and examined their cytolytic, cholesterol-binding, and gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-inducing activities. rLLO529 exhibited both IFN-γ-inducing and cytolytic activities. Four truncated rLLOs possessing different C termini, which did not exert either cytolytic or cholesterol-binding activity, stimulated IFN-γ production in normal spleen cells. However, a truncated rLLO corresponding to domain 4 (rLLO416-529) did not exhibit IFN-γ-inducing activity, whereas it did bind to immobilized cholesterol. In addition, though the hemolysis induced by rLLO529 was inhibited by rLLO416-529, such inhibition was not detected upon rLLO529-induced IFN-γ production. These data indicated that domain 4 was responsible for binding of LLO to membrane cholesterol followed by oligomerization and pore formation by the entire LLO molecule. In contrast, the other part of LLO, corresponding to domain 1-3, was essential for IFN-γ-inducing activity. These findings implied a novel aspect of the function of LLO as a bacterial modulin.

Listeria monocytogenes is a gram-positive, facultative intracellular bacterium which is responsible for sporadic but severe infections in humans and other animal species (18, 28). The major virulence factor of this bacterium essential for intracellular survival inside professional phagocytes is listeriolysin O (LLO), a pore-forming cytolysin (15). Based on the loss of escape from the phagosomal compartment into the cytosolic space of macrophages in LLO-deficient mutants, LLO is believed to lyse the phagosomal membrane and enable L. monocytogenes to gain access to the cytosol, resulting in intracellular parasitism (6, 17, 25).

LLO has been purified from culture supernatant of L. monocytogenes as a homogenous protein of approximately 60 kDa (10, 14). The gene encoding LLO, hly, has been cloned and sequenced, and the amino acid sequence of LLO has been determined (8, 19). LLO is a member of the family of thiol-activated cytolysins (TACYs), including streptolysin O (SLO), pneumolysin (PLY), and perfringolysin O (PFO) (1). An important feature of the TACYs is the presence of a highly conserved undecapeptide sequence (ECTGLAWEWWR) in the C-terminal region that is believed to be essential for the hemolytic activity. Conversion of the unique cysteine residue located within the undecapeptide of SLO (24), PLY (27), and LLO (20) to alanine by site-directed mutagenesis resulted in a minor loss of activity. In addition, pyolysin, a TACY from Arcanobacterium pyogenes, is reported to contain no cysteine residue in the undecapeptide (5). In contrast, a drastic decrease in hemolytic activity was observed after replacement of one of the three hydrophobic tryptophan residues in the undecapeptide of LLO, suggesting a critical role of the tryptophan residue(s) for the expression of its activity (20). A similar result has been reported regarding the importance of tryptophan in the hemolytic activity of PFO (29).

Apart from the well-known cytolytic activity of LLO, we have reported that LLO is a potent inducer for cytokines in murine cells. Purified LLO was able to stimulate macrophages to produce interleukin-1 (32) and induce various cytokines in spleen cells in vitro (22). Though the hemolytic activity of LLO is known to be blocked by cholesterol (16), its cytokine-inducing ability was not affected by the cholesterol treatment (22, 34). It was suggested that the cytolytic activity of LLO could be dissociated from its cytokine-inducing ability. In the present study, to define the dissociation of hemolytic activity from cytokine-inducing ability of LLO, we constructed recombinant full-length LLO (rLLO) and various truncated LLOs. In a previous study using purified native LLO, a striking production of IFN-γ was observed (22), and it has been shown that IFN-γ plays an important role especially in inducing protective immunity to L. monocytogenes (33). Therefore, we compared the various rLLOs for cytolysis, cholesterol-binding and IFN-γ induction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Extraction of chromosomal DNA from L. monocytogenes.

Chromosomal DNA was prepared according to the method of Flamm et al. (9). Briefly, L. monocytogenes strain EGD was grown overnight in 5 ml of brain heart infusion broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 1 min. Bacteria were washed with 0.1× SSC (0.015 M NaCl, 0.0015 M sodium citrate) and suspended in 0.6 ml of lysozyme solution (2.5 mg of lysozyme per ml in 0.01 M sodium phosphate and 20% sucrose [pH 7.0]), followed by incubation for 1 h at 37°C. The mixture was added with 5.4 ml of proteinase K solution (500 μg/ml in 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, and 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. DNA was isolated by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation and used as a template for PCR amplification of hly.

Construction and purification of mature and truncated LLOs.

The hly gene, encoding mature LLO, and the genes coding for various portions of LLO were amplified by PCR with 5′ primers containing BamHI sites (hly26, hly59, or hly416) and 3′ primers containing PstI sites (hly529, hly493, hly482, or hly415). The sequences of forward and reverse primers used in this study are listed in Table 1. The target DNA and amplified PCR fragments were sequenced with an ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) to confirm that mutations were not introduced during the course of PCR amplification with a GeneAmp PCR system 9700 (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems). The PCR fragments were digested with BamHI and PstI and ligated into pQE-31 vectors (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan) digested with the same enzymes. Recombinant plasmid was electroporated into Escherichia coli SG13009, and expression of six-His-tagged rLLOs was induced by incubation with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) at 25°C for 2 to 6 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 15 min, suspended in lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4 [pH 8.0], 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 1 mg of lysozyme per ml, 200 U of DNase), and disrupted by vortexing with 0.1-mm zirconia-silica beads. The soluble fraction was collected by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min, and His-tagged rLLOs were purified with a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid column (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Contaminating lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was extensively removed by using Detoxi-Gel endotoxin-removing gel (Pierce Chemical Company, Rockford, Ill.). The level of LPS was determined by a Limulus color KY test (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan). Protein concentration was measured with a protein assay reagent (Nacalai), and purity was determined by Coomassie blue staining and Western blotting after sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). A monoclonal anti-His tag antibody (penta·His antibody; Qiagen) and a polyclonal anti-LLO antibody raised in rabbits by repeated immunization with purified LLO from culture supernatant of L. monocytogenes were used for Western blot analysis.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Primer | Nucleotide sequence (5′-3′)a |

|---|---|

| Forward | |

| hly26 | CGATGGATCCTGATGCATCTGCATTCAATAAAG |

| hly416 | CGATGGATCCTGATGGAAAAATTAACATCGA |

| hly59 | CGATGGATCCTGATGAAATCGATAAGTATATAC |

| Reverse | |

| hly529 | ACGCCTGCAGTTCGATTGGATTATCTACACTATTAC |

| hly493 | ACGCCTGCAGTCTCCACCATTCCCAAGCT |

| hly482 | ACGCCTGCAGTTTAGCGTAAACATTAATATTTC |

| hly415 | ACGCCTGCAGTGTATAAGCTTTTGAAGTTGT |

The added restriction sites are underlined (BamHI for forward primers, PstI for reverse primers).

Hemolytic and cytolytic activities of rLLOs.

The hemolytic activity of rLLOs was determined by the level of hemoglobin released from 0.5% sheep red blood cells (SRBC). Briefly, various concentrations of rLLOs that had been treated with 10 μg of cholesterol per ml or left untreated were incubated with 0.5% SRBC in a total volume of 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 37°C for 30 min. After centrifugation at 800 × g for 10 min, the supernatant was collected and the absorbance of hemoglobin at 415 nm was measured. One hemolytic unit was defined as the amount of rLLOs that caused 50% hemoglobin release from 100 μl of 0.5% SRBC. In some experiments, SRBC were treated with rLLO416-529, corresponding to domain 4 of LLO, at 37°C for 1 h and hemolysis of the pretreated SRBC by full-length rLLO was examined.

The cytolytic activity was also determined by measuring the level of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released from macrophage-like cell line J774.1. Cells were suspended in culture medium consisting of RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco BRL, Life Technologies, Inc., Rockville, Md.) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 5 μg of gentamicin per ml and plated at 1.0 × 105 cells per well in a 48-well flat-bottomed tissue culture plate. After incubation at 37°C overnight, cells were washed and incubated with various doses of rLLOs for 6 h. The culture supernatant was collected, and the level of LDH was measured with an LDH cytotoxicity detection kit (Takara Shuzo Co., Shiga, Japan). In order to confirm that binding of LLO to membrane cholesterol was essential for the cytolytic activity, full-length rLLO was treated with 10 μg of free cholesterol per ml and the cytotoxicity was assayed.

Binding activity of rLLOs to cholesterol.

Various amounts of cholesterol were spotted on a thin-layer chromatography (TLC) sheet (Polygram Sil G; Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). The sheet was dried, soaked overnight at 4°C in buffer A, consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 200 mM NaCl, and 25% Block Ace (Dainippon Pharmaceutical Co., Osaka, Japan), and incubated with 100 nM rLLOs dissolved in buffer A for 1 h at room temperature with constant agitation. The sheet was washed six times with buffer A and incubated with a monoclonal anti-His tag antibody for 1 h, followed by further incubation for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, Calif.). The sheet was washed six times, and spots were detected with a peroxidase stain kit for immunoblotting (Nacalai). In some experiments, in order to determine whether rLLO416-529 (domain 4) inhibits the binding of rLLO529 to cholesterol, the TLC sheet that was spotted with cholesterol (0.06 μg) was treated with various concentrations of rLLO416-529 for 1 h at room temperature with constant agitation. After several washes, the sheet was incubated with 50 nM rLLO529 for 15 min. Silica gel in an area where cholesterol was spotted was scraped off from the sheet and boiled in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and the supernatant was subjected to Western blotting. In order to quantitatively detect the binding activity, the assay was carried out with a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane instead of the TLC sheet (2). Briefly, various concentrations of cholesterol dissolved in chloroform-ethanol (1:1) solution were plated in a 96-well filtration plate that had an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) at the bottom and allowed to dry overnight. The cholesterol-coated wells were treated with blocking buffer consisting of 4% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum in PBS for 1 h, and 100 μl of 2 nM rLLOs in blocking buffer was added to each well. After 1 h of incubation, wells were washed four times with blocking buffer and sequentially treated with monoclonal anti-His tag antibody and HRP-rabbit anti-mouse IgG. rLLO bound to cholesterol was quantified by the addition of 100 μl of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) in phosphate-citrate buffer (pH 5.0) containing 0.01% H2O2 and measurement of the absorbance at 450 nm after termination of the reaction with 100 μl of 0.18 M H2SO4.

Production of IFN-γ induced by rLLOs.

C3H/HeN mice were used for experiments at 7 to 9 weeks of age. Normal spleen cells were plated at 2.5 × 106 per well in a 48-well flat-bottomed tissue culture plate and stimulated with 100 μl of various concentrations of rLLOs for 24 h. In some experiment, spleen cells were first treated with various concentrations of rLLO416-529 for 1 h on ice and then stimulated with 50 nM rLLO529 for 24 h. The culture supernatant was collected, and the level of IFN-γ was measured by enzyme immunoassay as follows. The supernatants and IFN-γ standard were plated in the wells of a Nunc immunoplate (Nalge Nunc Int., Tokyo, Japan) which had been coated with 1.5 μg of rat anti-mouse IFN-γ antibody (Endogen, Woburn, Mass.) per ml and treated with 25% Block Ace to inhibit nonspecific binding. The plate was incubated for 1 h, washed with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20, and sequentially incubated with biotin-conjugated anti-mouse IFN-γ monoclonal antibody (Endogen) and HRP-conjugated streptavidin (Endogen). IFN-γ was detected by the addition of 50 μg of TMB per ml in phosphate-citrate buffer (pH 5.0) containing 0.01% H2O2 and measurement of the absorbance at 450 nm after the addition of 0.18 M H2SO4.

Statistical analysis.

All assays for hemolytic, cytolytic, cholesterol-binding, and IFN-γ-inducing activities were independently repeated three times, and similar results were obtained. Representative data were expressed as means ± standard deviations of triplicate determinations. Statistical significance was analyzed by Student's t test.

RESULTS

Construction of rLLOs.

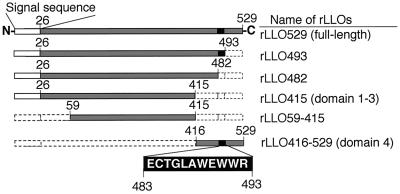

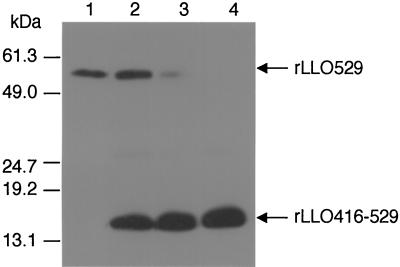

Based on the DNA sequence of hly, coding for LLO (19), various rLLOs were constructed. In addition to the full-length LLO without a signal sequence (rLLO529), we constructed three rLLOs with the C terminus truncated (rLLO493, rLLO482, and rLLO415), one with the N terminus truncated (rLLO416-529), and one with both termini truncated (rLLO59-415) (Fig. 1). Mature LLO obtained from culture supernatant of L. monocytogenes was 504 amino acids in length, with a molecular mass of 55.8 kDa (19). Because rLLO529 contains six histidines at the N terminus and an extra 10 amino acids encoded by the DNA sequence of the vector, the predicted molecular mass was 56.7 kDa. The size of purified rLLO529 on an SDS-PAGE gel was in agreement with this value (Fig. 2A). Each rLLO could also be observed at the position corresponding to each predicted molecular mass as a single band on SDS-PAGE gels (Fig. 2A) and immunoblots (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 1.

Construction of various rLLOs. The amino acid sequence is numbered from the N terminus. Gray bars represent polypeptide regions of full-length and truncated LLOs. The filled box in the LLO structure represents a region of the undecapeptide (ECTGLAWEWWR; residues 483 to 493) which is common among thiol-activated cytolysins.

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis for the purity of rLLOs. The purified rLLOs were subjected to SDS-PAGE with a 10 to 20% gradient gel. (A) The gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. (B) The proteins were electroblotted to a PVDF membrane, and Western blotting was performed with anti-His tag antibody. The positions of molecular mass standards are indicated on the left. Lanes: A, rLLO529; B, rLLO493; C, rLLO482; D, rLLO415; E, rLLO59-415; F, rLLO416-529

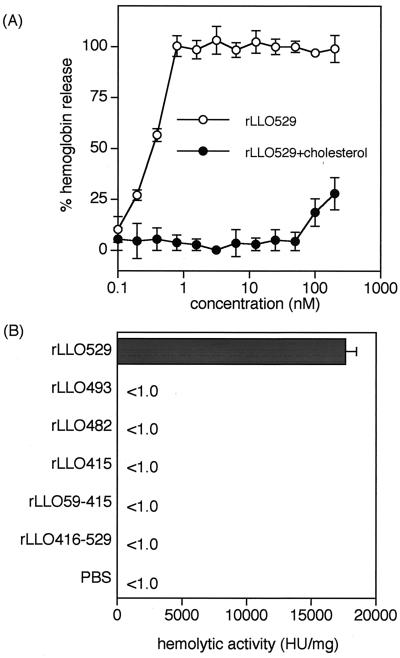

Hemolytic activity of rLLOs.

The hemolysis induced by rLLO529 was dose dependent, and the maximum activity was detectable at as low as 1 nM (Fig. 3A). The hemolytic activity of rLLO529 was calculated to be about 18,000 hemolytic units/mg of protein (Fig. 3B) and was almost completely inhibited by pretreatment with cholesterol (Fig. 3A). At higher concentrations (100 and 200 nM), however, the hemolysis was markedly decreased but not completely inhibited by treatment with cholesterol. This appeared to be due to the insufficient amount of cholesterol to block the hemolytic activity, since there was a limit of the solubility of cholesterol in an aqueous phase. In contrast to rLLO529, no truncated rLLOs exhibited detectable hemolytic activity. These data indicated that the C-terminal portion of LLO was essential in the hemolytic process, whereas pore formation does not take place by domain 4 of LLO (rLLO416-529) alone.

FIG. 3.

Cholesterol-dependent hemolysis induced by rLLO529 and comparison of hemolytic activity among rLLOs. (A) rLLO529 (1,000 nM) was serially diluted twofold with PBS and treated with cholesterol (10 μg/ml) or left untreated. Four volumes of SRBC suspension was added to make a final concentration of 0.5%, and the suspension was incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Hemolysis was measured by release of hemoglobin in the supernatant. (B) Hemolysis caused by rLLOs was measured as described above. HU, hemolytic units.

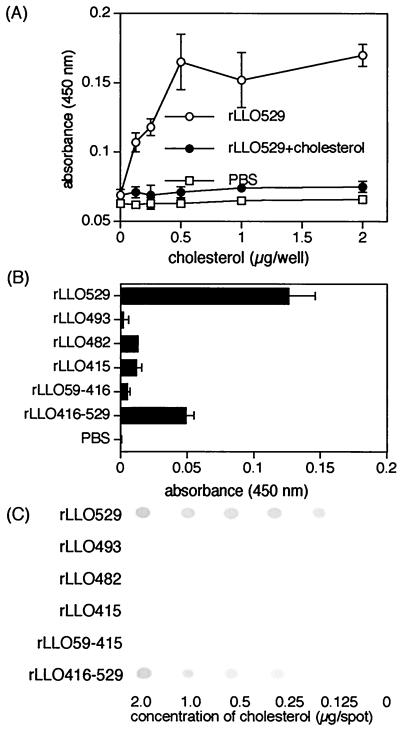

Cholesterol-binding activity of rLLOs.

The cholesterol-binding activity of rLLOs was determined by the level of rLLOs bound to cholesterol immobilized on a PVDF membrane or a TLC sheet. rLLO529 had a significant level of cholesterol-binding activity. The binding increased depending on the dose of cholesterol and reached the maximum at 0.5 μg of cholesterol (Fig. 4A). Treatment of rLLO529 with free cholesterol abolished the binding to immobilized cholesterol. In contrast, all the rLLOs truncated at the C terminus (rLLO493, rLLO482, rLLO415, and rLLO59-415) exhibited no cholesterol-binding activity (Fig. 4B). A similar result was obtained in the experiment using a TLC sheet (Fig. 4C). Cholesterol-binding activity was exhibited by rLLO416-529, a truncated protein corresponding to domain 4 of LLO, though its activity was somewhat lower than that of rLLO529 (Fig. 4B and C). These data indicated that the C-terminal portion of LLO was critical for cholesterol binding and that there was a significant correlation between the binding activity to cholesterol and hemolytic activity.

FIG. 4.

Binding of rLLOs to immobilized cholesterol. (A) Different amounts of cholesterol were plated in 96-well microtiter plates with PVDF membranes at the bottom. Cholesterol-treated or untreated rLLO529 (2 nM) was added, and the wells were incubated with anti-His tag antibody followed by HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. rLLO529 bound to immobilized cholesterol was detected by the addition of TMB to the wells. (B) Cholesterol (0.5 μg) was plated in the PVDF membrane-containing 96-well plates. Recombinant LLOs were adjusted at 2 nM, and the binding activities to cholesterol were determined. (C) Various concentrations of cholesterol were spotted on TLC plates. TLC plates were incubated with 100 nM rLLOs and then incubated with monoclonal anti-His tag antibody followed by HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. Binding of rLLOs to cholesterol was detected by peroxidase staining.

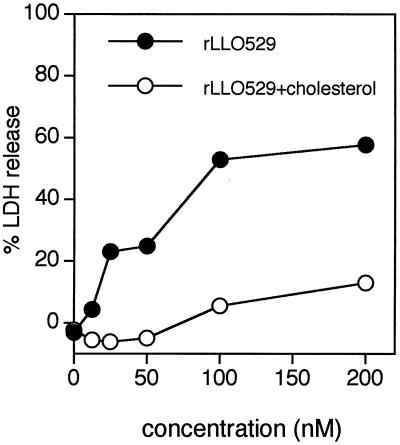

Cytotoxicity of rLLOs for macrophage.

Cytotoxicity of rLLOs for macrophage-like cell line J774.1 was determined by measuring the release of LDH. J774.1 cells were incubated with various concentrations of rLLO529 that had been treated with cholesterol or left untreated, and the culture supernatant was collected 6 h after incubation. As was the case with the hemolytic activity, rLLO529 exhibited a dose-dependent cytotoxicity to J774.1 cells and the activity was almost completely blocked by pretreatment with cholesterol (Fig. 5). At doses over 50 nM, however, the activity was diminished but not completely inhibited by the cholesterol treatment, indicating the insufficient blockade of the cytotoxicity by cholesterol as seen with the hemolytic activity of rLLO529. The cytotoxicity of truncated rLLOs for J774.1 cells was similar to that for hemolysis (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Cytotoxicity of rLLO529 for J774.1 cells. J774.1 cells (105 cells) were cultured overnight in 48-well plate. The supernatant was removed, and various concentrations of rLLO529 were added with or without cholesterol treatment. LDH released in the supernatant was measured 6 h after addition of rLLO529 to the cells.

IFN-γ-inducing ability of rLLOs.

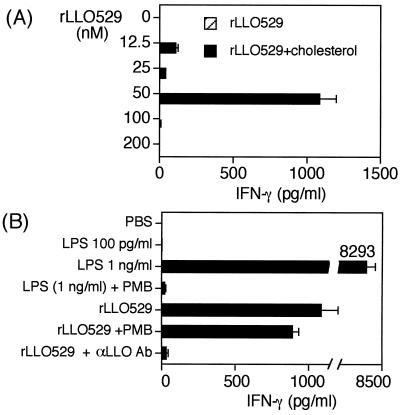

Normal spleen cells were stimulated for 24 h with rLLO529 that had been treated with or without cholesterol, then the level of IFN-γ was assayed by ELISA. IFN-γ production was not observed in cells incubated with rLLO529 that had not been cholesterol treated. In contrast, cholesterol-treated rLLO529 was capable of inducing IFN-γ production at 50 nM (Fig. 6A). At over 50 nM, however, rLLO529 did not induce IFN-γ production. The absence of IFN-γ-inducing activity at higher concentrations appeared to be due to the cytotoxicity remaining even after treatment with cholesterol (Fig. 5).

FIG. 6.

IFN-γ production by normal spleen cells stimulated with rLLO529. (A) Normal spleen cells were stimulated for 24 h with various concentrations of rLLO529 which had been treated with cholesterol or left untreated. The supernatant was collected and the level of IFN-γ was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. (B) Normal spleen cells were stimulated with 50 nM cholesterol-treated rLLO529 or LPS (0.1 and 1 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of polymyxin B (PMB; 0.5 μg/ml) and anti-LLO antibody (Ab) (1 μg/ml) for 24 h.

In order to rule out the possible involvement of contaminating LPS in IFN-γ induction, recombinant proteins were passed extensively through an LPS-removing column. The amount of LPS in the working concentration of rLLO preparations was at most 10 pg/ml. As shown in Fig. 6B, IFN-γ production was not induced even with 100 pg of LPS per ml, a dose 10 times higher than that in rLLO samples. In addition, the IFN-γ-inducing activity was not affected by polymyxin B, whereas the response to 1 ng of LPS per ml was completely inhibited by the same treatment. Furthermore, we found that IFN-γ production induced by rLLO529 was abolished by anti-LLO polyclonal antibody. These data clearly showed that rLLO itself was able to stimulate spleen cells to produce IFN-γ.

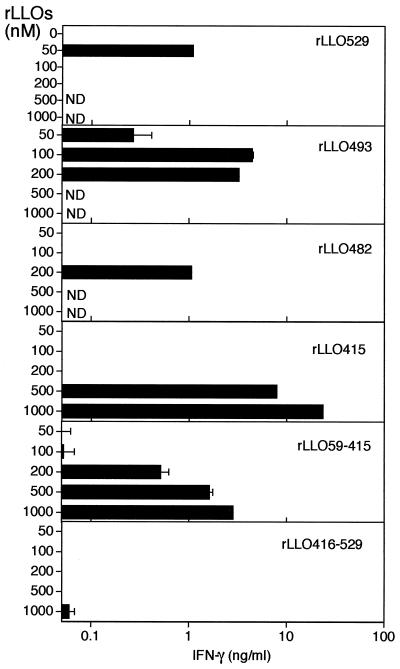

Based on the fact that cytokine-inducing activity of rLLO529 was expressed only when its cytotoxicity was abolished, there was a possibility that two different activities were linked to different domains of the LLO molecule. To address this possibility, we tested the IFN-γ-inducing activity of rLLO preparations with the C-terminal truncation that lacked the cytotoxic activity. Full-length LLO (rLLO529) induced IFN-γ production at 50 nM, but not at the doses exhibiting cytotoxicity (Fig. 7). On the other hand, rLLO493 was capable of inducing IFN-γ production at doses as high as 200 nM. The level of IFN-γ induced by 100 to 200 nM rLLO493 was significantly higher than that detected at 50 nM. This suggested that optimal dose of rLLO529 and truncated rLLOs for IFN-γ production was higher than 50 nM, at which the cytotoxicity could be inhibited by cholesterol treatment. As expected, a high level of IFN-γ production was also induced upon stimulation with rLLO482, rLLO415, and rLLO59-415 at higher doses, while we could not compare the activity at all concentrations because the highest available concentration was limited in some preparations. In contrast with these rLLOs, rLLO416-529 was not able to induce IFN-γ production even at 1,000 nM, suggesting that domain 4 of LLO is critically involved in hemolytic activity but not in IFN-γ-inducing activity. Based on these results, it was likely that the cytokine-inducing ability of LLO was linked to domain 1-3 and domain 4 was not required. However, rLLO529 showed IFN-γ-inducing activity at 50 nM, whereas rLLO415 did not. It was suggested that domain 4 plays some role in facilitating IFN-γ induction by the whole molecule.

FIG. 7.

IFN-γ-inducing activity of rLLO529 and five truncated LLOs. Normal spleen cells were stimulated with various concentrations of cholesterol-treated rLLOs for 24 h, and the level of IFN-γ production was determined. ND, not done.

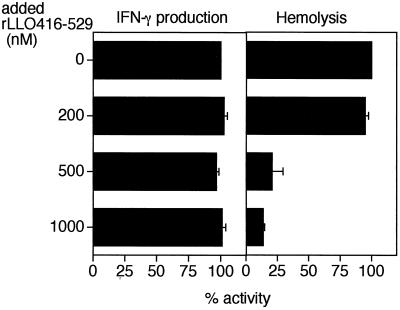

Involvement of domain 4 in hemolysis but not in IFN-γ production induced by full-length LLO.

In order to confirm the dissociation between hemolysis and IFN-γ production induced by rLLO529 on a molecular basis, we have examined whether rLLO416-529 (domain 4) inhibits IFN-γ induction and hemolysis caused by rLLO529. SRBC were treated with rLLO416-529 and subjected to hemolysis assay as the target cells. When SRBC were pretreated with an excess amount of rLLO416-529, there was a decrease in the level of hemolysis caused by rLLO529 (Fig. 8), indicating that rLLO416-529 was able to block the hemolytic process. In contrast, IFN-γ production induced by 50 nM rLLO529 was not inhibited even when cells were treated with 1,000 nM rLLO416-529. This result indicated that the binding of rLLO529 to cells via domain 4 was not required for the induction of IFN-γ production (Fig. 8). Next, we examined whether the inhibition of hemolysis by rLLO416-529 was due to the inhibition of the binding of rLLO529 to cholesterol. A TLC sheet that had been spotted with cholesterol was first treated with rLLO416-529 at different concentrations. After several washes, the sheet was incubated with rLLO529 and the binding of rLLO529 to cholesterol was determined by immunoblotting. The amount of rLLO529 bound to cholesterol was shown to decrease with increasing doses of rLLO416-529 (Fig. 9). The binding of rLLO529 (50 nM) was markedly inhibited when the sheet was pretreated with 1,000 nM rLLO416-529 and hardly detected upon pretreatment with 2,000 nM domain 4, indicating that rLLO416-529 competitively inhibited the binding of rLLO529 to cholesterol.

FIG. 8.

Inhibitory effect of rLLO416-529 (domain 4) on hemolytic activity but not on IFN-γ-inducing activity of rLLO529. Normal spleen cells were treated with various concentrations of rLLO416-529 for 1 h at 4°C and were stimulated with 50 nM cholesterol-treated rLLO529 for 24 at 37°C. The supernatant was collected, and the IFN-γ in the supernatant was measured. SRBC (1%) were treated with various concentrations of rLLO416-529 for 1 h at 4°C. rLLO529 was added to the SRBC suspension at 50 nM, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The hemolysis caused by rLLO529 was determined. The inhibitory activity of rLLO416-529 for IFN-γ production and hemolysis was expressed as percent decrease of activity in the presence of rLLO416-529.

FIG. 9.

Inhibitory effect of rLLO416-529 on the binding of rLLO529 to cholesterol. Cholesterol (0.06 μg) was spotted on a TLC sheet. The sheet was treated with 0 (lane 1), 500 (lane 2), 1,000 (lane 3), and 2,000 (lane 4) nM rLLO416-529 for 1 h. After several washes, the sheet was incubated with 50 nM rLLO529 for 15 min. Silica gel was scraped off, and bound rLLO416-529 and rLLO529 were detected by Western blotting using anti-His tag antibody.

DISCUSSION

LLO, a 58-kDa cytolytic protein toxin produced by the intracellular pathogen L. monocytogenes, belongs to a family of TACYs (13). PFO produced by Clostridium perfringens is a member of this family. Recently, the three-dimensional structure of PFO was determined to consist of four domains, including the continuous domain 1-3, involved in polymerization, and domain 4, harboring the membrane-binding portion of the cytolysin (26). The Trp-rich undecapeptide conserved in all TACYs is present in domain 4 in the C-terminal region and is thought to be involved in the formation of a hydrophobic pocket that renders TACYs capable of binding cholesterol (1). Because of the high homology at both DNA and amino acid sequence levels among various TACYs, LLO appears to have a domain structure similar to that of PFO (13).

In contrast to the well-established cytolytic activity of LLO, the ability to induce host cytokine, which we have reported (22, 33), is a completely different biological activity of LLO. In the present study, the structural requirements of the LLO molecule for cytolytic and cytokine-inducing abilities were compared. For that purpose, we constructed various rLLO preparations with truncations (Fig. 1 and 2). The full-length LLO (rLLO529) exhibited a hemolytic activity at a concentration as low as 1 nM against SRBC, and hemolysis was abolished by treatment with cholesterol up to 50 nM (Fig. 3). rLLO529 also showed a similar pattern of cytolytic activity against J774.1 cells, and significant activity was detected at the concentration above 12.5 nM (Fig. 5). No recombinants with truncations at the N and/or C termini exhibited hemolytic activity regardless of the presence or absence of the Trp-rich undecapeptide (residues 483 to 493). Binding to cholesterol was abolished in all four preparations truncated at the C terminus, in which one possessed the undecapeptide and three did not. In contrast, rLLO416-529, representing domain 4, was able to bind to cholesterol (Fig. 4). It was suggested that the intact structure of domain 4 was required for binding to membrane cholesterol, resulting in pore formation, and that the presence of the Trp-rich undecapeptide is not sufficient. This result was consistent with the findings that C-terminal truncation of PFO (30) and PLY (3, 23) resulted in the loss of erythrocyte-binding activity even if the Trp-rich undecapeptide is present. The dissociation between membrane binding and hemolysis of LLO was also reported in a study using monoclonal antibodies directed against different epitopes of LLO (7). The cytolytic process consists of at least four steps: binding to cholesterol in membranes, insertion into the membrane, oligomerization, and eventual pore formation (4). The present results suggested that truncation of the C terminus in LLO mainly affects the binding via membrane cholesterol.

The main purpose of the present study was to examine whether there is any difference in the structural dependency between the cytolytic activity and the cytokine-inducing ability of LLO. IFN-γ was produced after stimulation of spleen cells with the full-length rLLO529 only after treatment with free cholesterol and not with untreated preparation (Fig. 6). The increase in the concentration for stimulation resulted in a decrease in the amount of IFN-γ produced. At the concentration of rLLO529 optimal for cytokine induction (50 nM), the truncated proteins appeared to have lost the IFN-γ-inducing ability; however, rLLO493, rLLO482, rLLO415, and rLLO59-415 were all active in cytokine induction when applied at higher concentrations (Fig. 7). It was interesting that cytokine-inducing activity of these truncated preparations was expressed without blocking with free cholesterol, since they have completely lost the cholesterol-binding and cytolytic activity. From the results obtained in the LDH release assay, it was clear that truncation eliminated the damage to the macrophage membrane (data not shown). It was possible that the remaining cytolytic activity which was not completely abolished by cholesterol treatment affected the cytokine induction by rLLO529 due to the limitation in the amount of cholesterol to be solubilized in aqueous phase.

The most significant level of cytokine induction, much higher than that by full-length rLLO, was observed with rLLO415, in which the cholesterol-binding domain was completely eliminated (Fig. 7). This preparation corresponds to domain 1-3 of LLO according to the comparison of amino acid sequence to that of PFO; therefore, this result implied that domain 1-3 is fully capable of inducing the cytokine response. The possibility that the LPS contaminating the sample was responsible for the quite high activity of rLLO415 should be ruled out. Treatment of this sample with polymyxin B at a dose of 0.5 μg/ml did not affect the activity. The level of LPS determined by Limulus assay never exceeded 10 pg/ml, which was not effective in the induction of this high level of IFN-γ in spleen cell culture. Moreover, IFN-γ production was abolished by anti-LLO antibody. From these observations, the results shown in Fig. 7 can be regarded as the activity of recombinant protein itself, not an artifact of contaminating LPS.

From the results presented here, it can be concluded that cholesterol-binding activity is not required for the expression of cytokine-inducing activity of LLO. Domain 1-3 appeared to be highly potent in the induction of IFN-γ production by naive spleen cells of mice, but there may be a contribution from domain 4 or the overall molecular structure consisting of domains 1 through 4 to the expression of cytokine-inducing activity in the full-length molecule, because rLLO truncated at the C terminus did not induce IFN-γ production at 50 nM whereas rLLO529 showed activity at the same dose. In a study using PFO, it was shown that treatment with cholesterol induces a conformational change of PFO (21). There is a possibility that the interaction of LLO with cholesterol in solution resulted in a conformational change of the LLO molecule, which leads LLO to exhibit high affinity for a putative receptor for cytokine production. Though it may be argued that binding of molecule to membrane cholesterol is not a prerequisite for cytokine induction, the mechanism of signal transduction resulting in IFN-γ induction remains to be elucidated. In a previous study, the production of IFN-γ in spleen cells after stimulation with native LLO was dependent on macrophages, and NK cells were the final source of IFN-γ (22). It was suggested that signaling for cytokine induction is initiated through the binding of LLO to some binding site or receptor molecule other than membrane cholesterol on macrophages. This assumption is in agreement with a report that pretreatment with cholesterol did not influence the binding of native LLO to erythrocytes and B lymphoma cell lines (12). As shown in Fig. 4, domain 4 is responsible for binding to cholesterol leading to cytolysis. The fact that rLLO415 was capable of inducing IFN-γ suggested the existence of a portion binding to a putative noncholesterol receptor. In this regard, the establishment of rLLO415 lacking the cytotoxicity may be useful in the analysis of signal transduction after LLO-macrophage interaction without interference by cytolytic activity. In addition, we have shown that native LLO was highly active as an adjuvant in the induction of Th1-dependent protective immunity against L. monocytogenes after immunization with a non-LLO-producing strain of L. monocytogenes when it was used after encapsulation into the cholesterol-lecithin liposome (31). Because of the absence of toxicity and the presence of enhanced cytokine-inducing ability in truncated LLO, it will also be interesting to apply this preparation to in vivo immunization, and such experiments are under way. In conclusion, the present results suggest a novel function of LLO as one of the cytokine-inducing bacterial modulins (11), which is dissociable from its well-established function as a membrane lytic protein toxin of L. monocytogenes.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the “Research for the Future” program from The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research B and C from The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, and a grant from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alouf, J. E. 1999. Introduction to the family of the structurally related cholesterol-binding cytolysins (‘sulfhydryl-activated' toxins), p. 443-456. In J. E. Alouf and J. H. Freer (ed.), The comprehensive sourcebook of bacterial protein toxin, 2nd ed. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 2.Aniagolu, J., G. M. Swartz, Jr., J. Dijkstra, J. W. Madsen, J. J. Raney, and S. J. Green. 1995. Analysis of anticholesterol antibodies using hydrophobic membranes. J. Immunol. Methods 182:85-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baba, H., I. Kawamura, C. Kohda, T. Nomura, Y. Ito, T. Kimoto, I. Watanabe, S. Ichiyama, and M. Mitsuyama. 2001. Essential role of domain 4 of pneumolysin from Streptococcus pneumoniae in cytolytic activity as determined by truncated proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 281:37-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Billington, S. J., B. H. Jost, and J. G. Songer. 2000. Thiol-activated cytolysins: structure, function and role in pathogenesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 182:197-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Billington, S. J., B. H. Jost, W. A. Cuevas, K. R. Bright, and J. G. Songer. 1997. The Arcanobacterium (Actinomyces) pyogenes hemolysin, pyolysin, is a novel member of the thiol-activated cytolysin family. J. Bacteriol. 179:6100-6106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cossart, P., M. F. Vincente, J. Mengaud, F. Baquero, J. C. Perez-Diaz, and P. Berche. 1989. Listeriolysin O is essential for virulence of Listeria monocytogenes: direct evidence obtained by gene complementation. Infect. Immun. 57:3629-3636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darji, A., K. Niebuhr, M. Hense, J. Wehland, T. Chakraborty, and S. Weiss. 1996. Neutralizing monoclonal antibodies against listeriolysin: mapping of epitopes involved in pore formation. Infect. Immun. 64:2356-2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domann, E., and T. Chakraborty. 1989. Nucleotide sequence of the listeriolysin gene from a Listeria monocytogenes serotype 1/2a strain. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:6404.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flamm, R. K., D. J. Hinrichs, and M. F. Thomashow. 1984. Introduction of pAMβ1 into Listeria monocytogenes by conjugation and homology between native L. monocytogenes plasmids. Infect. Immun. 44:157-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geoffroy, C., J. L. Gaillard, J. E. Alouf, and P. Berche. 1987. Purification, characterization, and toxicity of the sulfhydryl-activated hemolysin listeriolysin O from Listeria monocytogenes. Infect. Immun. 55:1641-1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henderson, B., S. Poole, and M. Wilson. 1996. Bacterial modulins: a novel class of virulence factors which cause host tissue pathology by inducing cytokine synthesis. Microbiol. Rev. 60:316-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs, T., A. Darji, N. Frahm, M. Rohde, J. Wehland, T. Chakraborty, and S. Weiss. 1998. Listeriolysin O: cholesterol inhibits cytolysis but not binding to cellular membranes. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1081-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs, T., A. Darji, S. Weiss, and T. Chakraborty. 1999. Listeriolysin, the thiol-activated haemolysin of Listeria monocytogenes, p. 511-521. In J. E. Alouf and J. H. Freer (ed.), The comprehensive sourcebook of bacterial protein toxin, 2nd ed. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 14.Jenkins, E. M., A. N. Njoku-Obi, and E. A. Adams. 1964. Purification of the soluble hemolysins of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 88:418-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kathariou, S., P. Metz, H. Hof, and W. Goebel. 1987. Tn916-induced mutations in the hemolysin determinant affecting virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 169:1291-1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kingdon, G. C., and C. P. Sword. 1970. Biochemical and immunological effects of Listeria monocytogenes hemolysin. Infect. Immun. 1:363-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhn, M., S. Kathariou, and W. Goebel. 1988. Hemolysin supports survival but not entry of the intracellular bacterium Listeria monocytogenes. Infect. Immun. 56:79-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Low, J. C., and W. Donachie. 1997. A review of Listeria monocytogenes and listeriosis. Vet. J. 153:9-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mengaud, J., M. F. Vicente, J. Chenevert, J. M. Pereira, C. Geoffroy, B. Gicquel-Sanzey, F. Baquero, J. C. Perez-Diaz, and P. Cossart. 1988. Expression in Escherichia coli and sequence analysis of the listeriolysin O determinant of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect. Immun. 6:766-772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michel, E., K. A. Reich, R. Favier, P. Berche, and P. Cossart. 1990. Attenuated mutants of the intracellular bacterium Listeria monocytogenes obtained by single amino acid substitutions in listeriolysin O. Mol. Microbiol. 4:2167-2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamura, M., N. Sekino-Suzuki, K. Mitsui, and Y. Ohno-Iwashita. 1998. Contribution of tryptophan residues to the structural changes in perfringolysin O during interaction with liposomal membranes. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 123:1145-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishibori, T., H. Xiong, I. Kawamura, M. Arakawa, and M. Mitsuyama. 1996. Induction of cytokine gene expression by listeriolysin O and roles of macrophages and NK cells. Infect. Immun. 64:3188-3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Owen, R. H. G., P. W. Andrew, G. J. Boulnois, and T. J. Michell. 1994. A role in cell-binding for the C-terminus of pneumolysin, the thiol-activated toxin of Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 121:217-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinkney, M., E. Beachey, and M. Kehoe. 1989. The thiol-activated toxin streptolysin O dose not require a thiol group for cytolytic activity. Infect. Immun. 57:2553-2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Portnoy, D. A., P. S. Jacks, and D. J. Hinrichs. 1988. Role of haemolysin for the intracellular growth of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Exp. Med. 167:1459-1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossjohn, J., S. C. Feil, W. J. McKinstry, R. K. Tweten, and M. W. Parker. 1997. Structure of a cholesterol-binding, thiol-activated cytolysin and a model of its membrane form. Cell 89:685-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saunders, F. K., T. J. Mitchell, J. A. Walker, P. W. Andrew, and G. J. Boulnois. 1989. Pneumolysin, the thiol-activated toxin of Streptococcus pneumoniae, does not require a thiol group for in vitro activity. Infect. Immun. 57:2547-2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuchat, A., B. Swaminathan, and C. V. Broome. 1991. Epidemiology of human listeriosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4:169-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sekino-Suzuki, N., M. Nakamura, K. Mitsui, and Y. Ohno-Iwashita. 1996. Contribution of individual tryptophan residues to the structure and activity of θ-toxin (perfringolysin O), a cholesterol-binding cytolysin. Eur. J. Biochem. 241:941-947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimada, Y., M. Nakamura, Y. Naito, K. Nomura, and Y. Ohno-Iwashita. 1999. C-terminal amino acid residues are required for the folding and cholesterol binding property of perfringolysin O, a pore-forming cytolysin. J. Biol. Chem. 274:18536-18542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanabe, Y., H. Xiong, T. Nomura, M. Arakawa, and M. Mitsuyama. 1999. Induction of protective T cells against Listeria monocytogenes in mice by immunization with a listeriolysin O-negative avirulent strain of bacteria and liposome-encapsulated listeriolysin O. Infect. Immun. 67:568-575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsukada, H., I. Kawamura, T. Fujimura, K. Igarashi, M. Arakawa, and M. Mitsuyama. 1992. Induction of macrophage interleukin-1 production by Listeria monocytogenes hemolysin. Cell. Immunol. 140:21-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang, J., I. Kawamura, and M. Mitsuyama. 1997. Requirement of the initial production of gamma interferon in the generation of protective immunity of mice against Listeria monocytogenes. Infect. Immun. 65:72-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshikawa, H., I. Kawamura, M. Fujita, H. Tsukada, M. Arakawa, and M. Mitsuyama. 1993. Membrane damage and interleukin-1 production in murine macrophages exposed to listeriolysin O. Infect. Immun. 61:1334-1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]