Abstract

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a key inflammatory mediator. It has been proposed to function as an important molecule that alerts the host of potential bacterial infection. Although highly conserved, LPS contains important structural differences among different bacterial species that can significantly alter host responses. For example, LPS obtained from Porphyromonas gingivalis, an etiologic agent for periodontitis, evokes a highly unusual host cell response. Human monocytes respond to this LPS by the secretion of a variety of different inflammatory mediators, while endothelial cells do not. In addition, P. gingivalis LPS inhibits endothelial cell expression of E-selectin and interleukin 8 (IL-8) induced by other bacteria. In this report the ability of P. gingivalis LPS to activate p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase was investigated. It was found that p38 MAP kinase activation occurred in response to P. gingivalis LPS in human monocytes. In contrast, no p38 MAP kinase activation was observed in response to P. gingivalis LPS in human endothelial cells or CHO cells transfected with human Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4). In addition, P. gingivalis LPS was an effective inhibitor of Escherichia coli-induced p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation in both endothelial cells and CHO cells transfected with human TLR-4. These data demonstrate that P. gingivalis LPS activates the LPS-associated p38 MAP kinase in monocytes and that it can be an antagonist for E. coli LPS activation of p38 MAP kinase in endothelial and CHO cells. These data also suggest that although LPS is generally considered a bacterial component that alerts the host to infection, LPS from P. gingivalis may selectively modify the host response as a means to facilitate colonization.

The innate host defense system protects mammalian hosts against microbial infection through an orchestrated response to the presence of nonself components (31, 32). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of the gram-negative bacterial cell wall, is a key structure recognized by a variety of different innate host defense proteins, allowing the host to “sense” a potential bacterial infection (8, 62). LPS is evolutionarily an ideal target, since it is a conserved structure found on a wide variety of pathogenic bacteria and is sufficiently different from host components to allow a safe selective response (38). However, there are important structural differences in LPS composition between different bacterial species, such as fatty acid acyl chain composition and charge, which can significantly affect the host response (33, 36, 42, 49, 64). Different binding affinities for LPS binding protein and CD14 may only partly explain the lowered inflammatory response to some LPS species that has been observed (14), consistent with the notion that the major role of LPS binding protein and CD14 is to concentrate LPS at host cell surfaces (65). Recently it has been demonstrated that cell surface Toll-like receptor (TLR) proteins participate in the ability of the host to discriminate different LPS structural features (6, 25, 30, 34, 47, 58, 66). These data suggest that one mechanism by which the innate host defense system recognizes different bacterial species relates to their unique LPS structural features.

Porphyromonas gingivalis is a gram-negative bacterium that is recognized as an important etiologic agent of human adult-type periodontitis (56). This bacterially induced chronic inflammatory disease affects a large proportion of the population and is characterized by resorption of alveolar bone surrounding the tooth root surface, resulting in the loss of permanent dentition (56). P. gingivalis LPS is unusual in that although it is able to activate human monocytes by a CD14-dependent mechanism (54) and binds sCD14 (14), it does not facilitate either E-selectin expression or interleukin 8 (IL-8) secretion from human umbilical cord vein vascular endothelial cells (16). In fact, this LPS is a natural antagonist for the human endothelial E-selectin and IL-8 response to Escherichia coli LPS and other oral bacteria (16). Studies with the mutant sCD14 proteins E47K and E47R that bind E. coli LPS but not P. gingivalis LPS (55) have demonstrated that sCD14 is not required for inhibition of E-selectin expression (13), ruling out competition for sCD14 binding as the mechanism for antagonism. Although the host inflammatory response to P. gingivalis LPS both in vivo (50) and in vitro (5) is significantly different from that observed with E. coli LPS, little is known concerning how this LPS may affect intracellular signaling pathways.

A key component of many intracellular signaling pathways are the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases (10, 45). This superfamily includes the extracellular signal response kinases (ERKs), c-jun N-terminal kinases, and the p38 family of kinases. Although LPS facilitates the activation of all three of these MAP kinases, numerous studies employing p38 MAP kinase-specific inhibitors have provided good evidence that many cellular responses to LPS require p38 activation (1, 2, 11, 41), consistent with a primary role for p38 activation in response to LPS (12, 26, 27, 29, 59). In this study the p38 MAP kinase response to P. gingivalis LPS was examined. It was found that p38 MAP kinase activation correlated with the ability of P. gingivalis to activate cells. In addition, P. gingivalis LPS was an effective inhibitor of E. coli-induced p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and preparation of LPS.

P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.; it was examined for purity, properly identified, and stored at −70°C. Cultures were made from frozen bacterial stocks to avoid repetitive subculture. Bacterial cells were grown for LPS isolation as follows: P. gingivalis was grown anaerobically at 37°C for 2 to 3 days in enriched Trypticase soy broth supplemented with heme, cysteine, and menadione. Strain 33277 was grown in a large batch culture by Lee Laboratories, Grayson, Ga., under similar conditions and shipped as frozen cell pellets.

P. gingivalis LPS was prepared by the cold MgCl2-ethanol procedure (17) followed by lipid extraction (21) and conversion to sodium salts (46). Purified LPS from E. coli 0111:B4 (Sigma) was obtained by the phenol-water method and was further purified by a Folch extraction (21) to remove contaminating phospholipids. LPS preparations were suspended in distilled water, and the absence of contaminating nucleic acid and protein was verified by measuring the optical densities at 280 and 260 nm. Colloidal gold staining (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Ca.) of the LPS preparations was performed as described by the manufacturer and revealed less than 1% protein contamination for both preparations. Gas chromatographic analysis for sugar and fatty acid composition revealed that the composition of these purified LPSs agreed with published data (42).

Cell culture.

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were prepared by collagenase (Worthington Biochemical, Freehold, N.J.) treatment of umbilical cords. Cultures were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Whittaker, Walkerville, Md.) supplemented with 20% adult bovine serum (JRH Bioscience, Lenexa, Kans.), HEPES buffer solution (10 mM), sodium pyruvate (1 mM), l-glutamine (2 mM), nonessential amino acids solution (GIBCO BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) (0.1 mM), endothelial cell growth supplement (25 μg/ml) (Collaborative Research, Lexington, Mass.), heparin (90 μg/ml) (Sigma), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Third-passage HUVEC plated in 100-mm-diameter tissue culture treated plates (Corning, Corning, N.Y.) and maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere were used in all experiments. Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells were prepared from the blood of healthy volunteers by Ficoll density centrifugation, and monocytes were subsequently purified from the mononuclear layer by adherence to plastic. Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells expressing human CD14 and human TLR4 were a gift of Douglas Golenbock, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Mass., and are described in reference 28. CHO cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum and supplemented with hygromycin, puromycin, or G418 as required to maintain selection.

MAP kinase assays.

Before stimulation, confluent HUVEC cultures were changed to an endothelial cell growth supplement-free medium with 10% adult bovine serum. The cells were stimulated with various concentrations of E. coli and/or P. gingivalis LPS. Similarly, CHO cells cultured overnight in RPMI 1640 containing 1% fetal bovine serum were stimulated for 30 min with LPS or other stimulants and treated as described for HUVEC. Monocytes were cultured with LPS or other stimulants for 30 min in RPMI 1640 containing 10% adult bovine serum.

After stimulation with E. coli and/or P. gingivalis LPS for various time periods, the cell monolayer was washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline. Total cellular protein was then extracted by lysing the cells in 500 μl of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, 137 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 1 μM sodium orthovanadate, 100 μM dithiothreitol, 200 μM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg of leupeptin/ml, 0.15 U of aprotinin/ml, 50 mM sodium fluoride, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 2.5 μg of pepstatin A/ml, 1 mM benzamidine) at 4°C. The protein concentration was determined by the (bicinchoninic acid) protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). Twenty micrograms of protein was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in 10% acrylamide gels and transferred to a Hybond-ECL nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.). The membrane was blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 5% nonfat milk and then incubated overnight with a dual phospho-specific ERK-1/ERK-2 MAP kinase (Thr202/Tyr204) monoclonal antibody (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) or dual phospho-specific p38 MAP kinase (Thr180/Tyr182) polyclonal antibody (New England Biolabs) at 4°C. The dual phospho-specific antibodies detect MAP kinase only when activated by dual phosphorylation. These antibodies, which are raised against human p38, are known to cross-react with mouse and rat p38 and were found to cross-react with hamster p38 as well. All membranes were then incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The blots were developed using the SuperSignal chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce) and exposed to Kodak XAR-5 film (Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, N.Y.). Densitometry by the NIH image program was used to quantitate optical density of the blots.

Statistics.

Each experiment generated one immunoblot that was subjected to densitometry; the number of times that each experiment was performed varied and is indicated in the figure legends. The data in each figure are presented as the mean and standard of error of the mean. Significant differences in either ERK or p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation levels due to the different experiential conditions were determined by the two-tailed t test employing the combined raw data. Differences were considered statistically significant at P values of <0.05.

RESULTS

P. gingivalis LPS does not activate ERK or p38 MAP kinase in human endothelial cells.

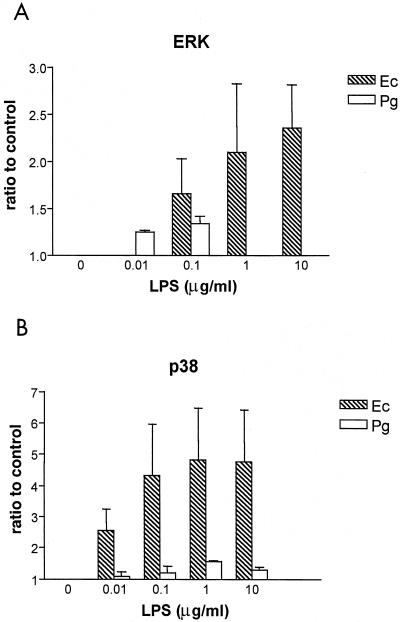

E. coli LPS induces phosphorylation of both ERK and p38 MAP kinase in human endothelial cells (4, 52), which is necessary for E. coli LPS activation of IL-8 (27, 29). Since P. gingivalis LPS does not facilitate the activation of this inflammatory mediator (15) or E-selectin (16), initial experiments were performed to determine the effect of P. gingivalis LPS on MAP kinase phosphorylation. Various concentrations of either E. coli LPS or P. gingivalis LPS were added to human endothelial cells, and the ratios of phosphorylated ERK and p38 MAP kinase to the levels for a unstimulated control were determined after a 30-min incubation (Fig. 1). E. coli LPS activated both ERK and p38 MAP kinase in a dose-dependent manner. The ratio of E. coli LPS-induced MAP kinase activation to the unstimulated control level was higher for p38 than for ERK MAP kinase. In contrast, P. gingivalis LPS either failed to induce phosphorylation levels of either MAP kinase over control values or induced minor increases at selected LPS concentrations.

FIG. 1.

MAP kinase activation in response to various doses of either E. coli or P. gingivalis LPS. HUVECs were stimulated with various concentrations of LPS (Ec, E. coli; Pg, P. gingivalis) as indicated on the horizontal axis. Total cellular protein was harvested after 30 min and subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with dual phosphospecific ERK (A) and p38 (B) antibodies. Gels were scanned for densitometry analysis, and the ratio of each LPS dose to an unstimulated control is shown. The data are presented as an averages from three separate experiments (each error bar indicates the standard error of the mean).

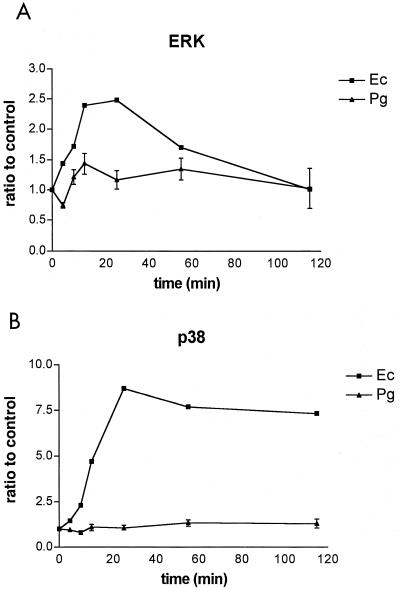

Time-dependent MAP kinase activation experiments were performed to determine if P. gingivalis LPS activated ERK or p38 MAP kinase with kinetics significantly different from that observed for E. coli LPS. E. coli LPS (0.1 μg/ml) or P. gingivalis LPS (1.0 μg/ml) was added to endothelial cells, and increases in the amounts of phosphorylated ERK and p38 MAP kinase compared to those for an unstimulated control were determined at select times for 2 h (Fig. 2). Maximum MAP kinase activation was observed for both ERK and p38 at 30 min following the addition of E. coli LPS. ERK phosphorylation decreased to unstimulated control values by the end of the 2-h time course, whereas p38 levels remained significantly elevated throughout the experiment. P. gingivalis LPS induced minor changes in ERK phosphorylation at early time points and had little or no effect on p38 phosphorylation throughout the 2-h experiment.

FIG. 2.

Time course of MAP kinase activation in response to either E. coli or P. gingivalis LPS. HUVECs were stimulated with E. coli LPS at a concentration of 0.1 μg/ml (triangles) or with P. gingivalis LPS at a concentration of 1 μg/ml (squares). Total cellular protein was harvested at the times indicated on the horizontal axis and subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with dual phosphospecific ERK (A) and p38 (B) antibodies. Gels were scanned for densitometry analysis, and the ratio of each LPS dose to an unstimulated control is shown. The data are presented as an average from two (E. coli) or four (P. gingivalis) separate experiments (each error bar indicates the standard error of the mean).

P. gingivalis LPS activates p38 MAP kinase in human monocytes.

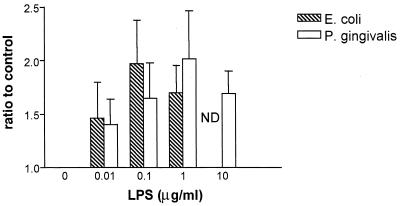

In contrast to studies with human endothelial cells, human monocytes respond to P. gingivalis LPS by the CD14-dependent secretion of inflammatory mediators (16, 54). It was therefore of interest to determine if human monocytes respond to P. gingivalis LPS by the activation of p38 MAP kinase. Human monocytes were stimulated with various concentrations of either E. coli LPS or P. gingivalis LPS (Fig. 3). In three separate experiments, these cells responded to P. gingivalis LPS by the stimulation of p38 MAP kinase with a response similar to that observed for E. coli LPS. These data demonstrate that P. gingivalis LPS can elicit the activation of p38 MAP kinase in human monocytes, although no response was observed when human endothelial cells were exposed to this LPS under identical conditions.

FIG. 3.

Human monocyte p38 MAP kinase activation in response to various doses of either E. coli or P. gingivalis LPS. Human monocytes were stimulated with various concentrations of LPS (from E. coli or P. gingivalis) as indicated on the horizontal axis. Total cellular protein was harvested after 30 min and subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with dual phosphospecific p38 antibody. Gels were scanned for densitometry analysis, and the ratio of each LPS dose to an unstimulated control is shown. The data are presented as averages from three separate experiments (each error bar indicates the standard error of the mean).

P. gingivalis LPS inhibits endothelial cell p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation in response to E. coli LPS but not in response to tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α).

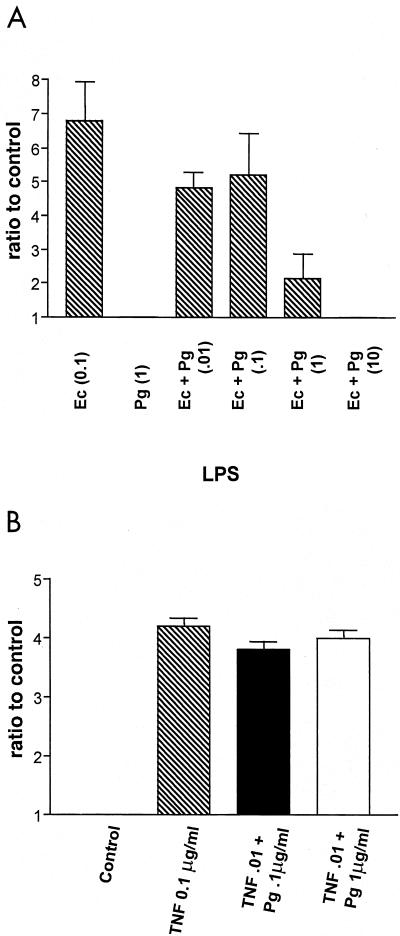

As mentioned above, activation of p38 MAP kinase is necessary for E. coli LPS activation of inflammatory mediators, including IL-8 (27, 29). Also, P. gingivalis LPS inhibits endothelial cell E-selectin and IL-8 responses to E. coli LPS by a mechanism which does not involve competition for binding to sCD14 (13). Therefore, one possible mechanism for inhibition of E. coli LPS endothelial cell responses by P. gingivalis LPS would be the blocking of p38 MAP kinase activation by interfering in the activation pathway after CD14 presentation of LPS to the cell. The ability of P. gingivalis LPS to inhibit endothelial cell p38 MAP kinase activation in response to E. coli LPS was examined next (Fig. 4). Various combinations of E. coli and P. gingivalis LPS representing different ratios of these two LPS species were added to endothelial cells, and increases in the amount of phosphorylated p38 MAP kinase compared to an that of the unstimulated control were determined after a 30-min incubation (Fig. 4A). E. coli LPS (0.1 μg/ml), when added alone, stimulated phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase; however, when combined with P. gingivalis LPS (1 μg/ml), p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation was significantly attenuated (P < 0.001 with nonpaired Student's t test). At a ratio of 100-fold excess P. gingivalis LPS to E. coli LPS, E. coli LPS-induced p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation was completely blocked by P. gingivalis LPS (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Inhibition of p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation by P. gingivalis LPS in response to E. coli LPS or TNF-α. (A) E. coli LPS (0.1 μg/ml) was mixed with various concentrations of P. gingivalis LPS (indicated on the horizontal axis) prior to the addition to HUVECs. E. coli (0.1 μg/ml) and P. gingivalis (1 μg/ml) LPSs were also added alone as indicated on the horizontal axis. (B) P. gingivalis LPS did not inhibit p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation in response to TNF-α. TNF-α (0.01 μg/ml) alone and premixed with P. gingivalis LPS (0.1 and 1 μg/ml) was added to HUVECs. Total cellular protein was harvested after 30 min and subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with dual phosphospecific p38 antibodies. Gels were scanned for densitometry analysis, and the ratio of TNF-α alone and in combination with P. gingivalis LPS to an unstimulated control is shown. The data are presented as an average from four (A) or three (B) separate experiments (each error bar indicates the standard error of the mean).

Although P. gingivalis LPS is an effective inhibitor of endothelial cell E-selectin (16) responses to E. coli LPS, it does not block either E-selectin expression or transcription in response to TNF-α (16), indicating that the mechanism of inhibition is unique to the LPS activation pathway. Therefore, the ability of P. gingivalis LPS to modulate p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation in response to TNF-α was examined (Fig. 4B). Initial experiments determined that 0.01 μg/ml represented the lowest dose of TNF-α that yielded maximal phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase (data not shown). Next, combinations of P. gingivalis LPS and TNF-α representing different ratios of these two components were added to endothelial cells, and the status of p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation was determined after a 30-min incubation (Fig. 4B). In contrast to the data obtained with E. coli LPS, combinations containing excess P. gingivalis LPS did not result in any significant decrease in the amount of p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation in response to TNF-α. This observation is consistent with the notion that P. gingivalis LPS interferes with endothelial cell activation at a site unique in the LPS activation pathway.

P. gingivalis LPS is a TLR-4 antagonist in CHO cells cotransfected with TLR-4 and mCD14.

TLR-4 represents a possible site where P. gingivalis LPS may act as an antagonist in the E. coli LPS activation pathway. First, TLR-4 is a key component of the CD14/E. coli LPS activation pathway (8, 32, 38, 62). Second, independent studies have demonstrated that different P. gingivalis LPS preparations may employ either TLR-4 (58) or TLR-2 (6, 30) to activate cells depending upon the cell type and or in vitro system employed. These studies indicate that although P. gingivalis LPS has the ability to interact with TLR-4, it may not always facilitate cellular activation. Therefore, the potential of P. gingivalis LPS to antagonize TLR-4-mediated E. coli LPS activation was examined in the CHO cells cotransfected with human TLR-4 and mCD14.

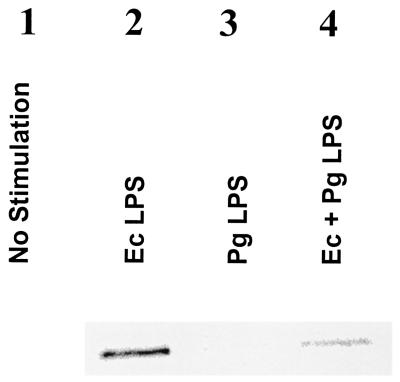

E. coli LPS (100 ng/ml) both with and without the addition of P. gingivalis LPS (10 μg/ml) was added to the CHO cell lines cotransfected with human TLR-4 and mCD14. The amount of p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation was determined after 30 min of coincubation by immunoblotting CHO cell extracts (Fig. 5). It was found that addition of E. coli LPS resulted in an increase in the amount of p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation (Fig. 5, lane 2). However, when the same concentration of E. coli LPS was premixed with P. gingivalis LPS prior to addition to the CHO cells, p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation was nearly abolished (Fig. 5, lane 4). This experiment demonstrates that p38 MAP kinase is activated in response to TLR-4 engagement of E. coli LPS in CHO transfected cells and that this activation is inhibited by P. gingivalis LPS.

FIG. 5.

P. gingivalis LPS is a TLR4 antagonist in CHO cells cotransfected with TLR4 and mCD14. CHO cells transfected with TLR4 and mCD14 were incubated with E. coli LPS (100 ng/ml) with or without 10 μg of P. gingivalis LPS/ml for 30 min in the presence of 1% normal human serum and lysed for determination of p38 by immunoblotting with phospho-specific p38 antibodies as described in the text. A representative blot was chosen from four identical experiments.

DISCUSSION

Although it is now clear that the TLR family of membrane proteins facilitates activation of host cells by LPS (34, 47, 58, 66), the subsequent pathways that lead to inflammatory mediator production are still being elucidated. Evidence demonstrates that both a Rac-1 (3) and a p38 MAP kinase dependent pathway (51) are activated after LPS or LTA interactions with TLRs. Endothelial cell secretion of IL-8 in response to LPS is dependent upon both pathways (29), which is consistent with other studies that have shown a key role for p38 MAP kinase in endothelial cells responses to E. coli LPS (27, 41, 52, 59). However, LPSs obtained from different bacterial species have significant variations in their abilities to activate host cells (5, 9, 16, 22, 40, 57), and it is not known if this correlates to their ability to activate p38 MAP kinase. For example, P. gingivalis LPS obtained from a variety of different strains (33277, 5083, 381, A7-A128, and A7436) in contrast to E. coli LPS fails to elicit E-selectin expression or IL-8 secretion 16; also unpublished observations) from human endothelial cells. However, both LPS species activate human monocytes, although the response to LPS obtained from P. gingivalis is both less potent (7, 16, 22, 43, 44, 60) and elicits a different pattern of inflammatory mediators (43, 60) relative to E. coli LPS. The present study demonstrated that p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation correlated with the ability of monocytes and endothelial cells to elicit secretion of inflammatory mediators in response to P. gingivalis LPS. Since p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation is one of the earliest events after LPS presentation to host cells, this correlation suggests that these two different cell types detect P. gingivalis LPS differently.

Two of the major differences between how monocytes and endothelial cells recognize LPS are the utilization of either the membrane (mCD14) or soluble (sCD14) form of CD14 (48) and TLR engagement (20). It has been demonstrated that mCD14 and sCD14 display different structural requirements for LPS binding (63). Therefore, it is possible that although P. gingivalis LPS binds both forms of CD14 (14, 54), it may bind them differently, leading to activation with mCD14 in monocytes (54) and failure to functionally engage P. gingivalis LPS/sCD14 complexes in the endothelial cell activation pathway (14). In addition, endothelial cells express a higher TLR-4/TLR-2 ratio than do human monocytes, and the ratio of these two TLRs may explain in part why endothelial cells respond to microbial components that engage TLR-4 but not TLR-2 (20). Therefore, the failure of P. gingivalis LPS to activate p38 MAP kinase in human endothelial cells is consistent with the notion that sCD14/P. gingivalis LPS complexes cannot functionally engage TLR-4 in these cells.

Existing data support the notion that TLR-4 may facilitate P. gingivalis LPS activation in some cell types but not others. For example, P. gingivalis LPS can employ TLR-4 (58) to facilitate gingival fibroblast activation, presumably by employing mCD14 that is expressed on these cells. However, the lack of p38 MAP kinase activation by P. gingivalis LPS in the TLR-4 mCD14 CHO transfected line reported here (Fig. 5), and previous observations with these cells by us and others where neither PGE2 secretion (6) nor CD25 expression (30) was detected in response to this LPS, indicate that TLR-4 may not always be able to facilitate cell activation with this LPS. Furthermore, in this report it is demonstrated that P. gingivalis LPS is an effective antagonist for E. coli LPS activation of p38 MAP kinase in the TLR-4/mCD14-transfected CHO and endothelial cells. Based upon these observations, we propose that in some cell types P. gingivalis LPS can be a functional antagonist for TLR-4 and forms an incomplete binding complex (19) that remains “locked” and unable to activate or dissociate effectively, blocking E. coli and other bacterial components from functionally interacting with this receptor, whereas in others cell types or cells expressing a different repertoire of innate host defense response molecules, P. gingivalis LPS can elicit inflammatory responses.

One possible in vivo manifestation of P. gingivalis LPS antagonism with endothelial cells may be modulation of the dynamic balance that exists between commensal dental plaque bacteria and the host response. The innate host response is critical to maintaining a clinically healthy periodontium (18, 61), and studies have shown that in healthy individuals a highly orchestrated protective response is found (18, 61). P. gingivalis, which resides in close proximity to the gingival epithelial cell surface, releases copious amounts of outer membrane vesicles containing LPS (23, 24) which can penetrate periodontal tissue (37, 39, 53) and have direct inhibitory effects on the highly vascularized tissue adjacent to the tooth root surface. The interruption of endothelial cell responses to LPS is similar to earlier observations (15, 35) demonstrating inhibition of IL-8 secretion after invasion of epithelial cells by viable P. gingivalis. Both of these observations are consistent with a bacterial colonization strategy that creates localized areas of paralysis of innate host defense by direct interaction with host cells. We propose that disruption in the periodontium of inflammatory mediator secretion that normally serves to protect the host from infection may lead to disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Colleen McKay and Emily Johnson for their help in preparing the manuscript.

Portions of this work were supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Dental and Craniofacial Research (DE 12768) and the Elam M. and Georgina E. Hack Memorial Research Fund.

Editor: R. N. Moore

REFERENCES

- 1.Ajizian, S. J., B. K. English, and E. A. Meals. 1999. Specific inhibitors of p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways block inducible nitric oxide synthase and tumor necrosis factor accumulation in murine macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide and interferon-gamma. J. Infect. Dis. 179:939-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arbabi, S., M. R. Rosengart, I. Garcia, S. Jelacic, and R. V. Maier. 1999. Priming interleukin 8 production: role of platelet-activating factor and p38. Arch. Surg. 134:1348-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arbibe, L., J. P. Mira, N. Teusch, L. Kline, M. Guha, N. Mackman, P. J. Godowski, R. J. Ulevitch, and U. G. Knaus. 2000. Toll-like receptor 2-mediated NF-kB activation requires a Rac1-dependent pathway. Nat. Immunol. 1:533-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arditi, M., J. Zhou, M. Torres, D. L. Durden, M. Stins, and K. S. Kim. 1995. Lipopolysaccharide stimulates the tyrosine phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinases p44, p42, and p41 in vascular endothelial cells in a soluble CD14-dependent manner. Role of protein tyrosine phosphorylation in lipopolysaccharide-induced stimulation of endothelial cells. J. Immunol. 155:3994-4003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bainbridge, B. W., and R. P. Darveau. 1997. Lipopolysaccharide from oral bacteria: role in innate host defense and chronic inflammatory disease, p. 899-913. In D. Morrison (ed.), Endotoxin in health and disease. Marcel Dekker, New York, N.Y.

- 6.Bainbridge, B. W., and R. P. Darveau. 2001. Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide: an unusual pattern recognition receptor ligand for the innate host defense system. Acta Odontol. Scand. 59:131-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bainbridge, B. W., R. C. Page, and R. P. Darveau. 1997. Serum antibodies to Porphyromonas gingivalis block the prostaglandin E2 response to lipopolysaccharide by mononuclear cells. Infect. Immun. 65:4801-4805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beutler, B. 2000. Tlr4: central component of the sole mammalian LPS sensor. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 12:20-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brade, L., S. Schramek, U. Schade, and H. Brade. 1986. Chemical, biological, and immunochemical properties of the Chlamydia psittaci lipopolysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 54:568-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunet, A., and J. Pouyssegur. 1997. Mammalian MAP kinase modules: how to transduce specific signals. Essays Biochem. 32:1-16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, C., Y. H. Chen, and W. W. Lin. 1999. Involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in lipopolysaccharide-induced iNOS and COX-2 expression in J774 macrophages. Immunology 97:124-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, C. C., and J. K. Wang. 1999. p38 but not p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for nitric oxide synthase induction mediated by lipopolysaccharide in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Mol. Pharmacol. 55:481-488. (Erratum, 55:1108.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunningham, M. D., J. Bajorath, J. E. Somerville, and R. P. Darveau. 1999. Escherichia coli and Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide interactions with CD14: implications for myeloid and nonmyeloid cell activation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 28:497-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cunningham, M. D., C. Seachord, K. Ratcliffe, B. Bainbridge, A. Aruffo, and R. P. Darveau. 1996. Helicobacter pylori and Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharides are poorly transferred to recombinant soluble CD14. Infect. Immun. 64:3601-3608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darveau, R. P., C. M. Belton, R. A. Reife, and R. J. Lamont. 1998. Local chemokine paralysis, a novel pathogenic mechanism for Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 66:1660-1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darveau, R. P., M. D. Cunningham, T. Bailey, C. Seachord, K. Ratcliffe, B. Bainbridge, M. Dietsch, R. C. Page, and A. Aruffo. 1995. Ability of bacteria associated with chronic inflammatory disease to stimulate E-selectin expression and promote neutrophil adhesion. Infect. Immun. 63:1311-1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darveau, R. P., and R. E. Hancock. 1983. Procedure for isolation of bacterial lipopolysaccharides from both smooth and rough Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Salmonella typhimurium strains. J. Bacteriol. 155:831-838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Darveau, R. P., A. Tanner, and R. C. Page. 1997. The microbial challenge in periodontitis. Periodontology 2000 14:12-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.da Silva Correia, J., K. Soldau, U. Christen, P. S. Tobias, and R. J. Ulevitch. 2001. Lipopolysaccharide is in close proximity to each of the proteins in its membrane receptor complex: transfer from CD14 to TLR4 and MD-2. J. Biol. Chem. 276:21129-21135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faure, E., O. Equils, P. A. Sieling, L. Thomas, F. X. Zhang, C. J. Kirschning, N. Polentarutti, M. Muzio, and M. Arditi. 2000. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide activates NF-kappaB through toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) in cultured human dermal endothelial cells. Differential expression of TLR-4 and TLR-2 in endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275:11058-11063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folch, J., M. Lees, and G. Stanley. 1957. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226:497-509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujiwara, T., T. Ogawa, S. Sobue, and S. Hamada. 1990. Chemical, immunobiological and antigenic characterizations of lipopolysaccharides from Bacteroides gingivalis strains. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136:319-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grenier, D., J. Bertrand, and D. Mayrand. 1995. Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles promote bacterial resistance to chlorhexidine. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 10:319-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grenier, D., and D. Mayrand. 1987. Functional characterization of extracellular vesicles produced by Bacteroides gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 55:111-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hajjar, A. M., D. S. O'Mahony, A. Ozinsky, D. M. Underhill, A. Aderem, S. J. Klebanoff, and C. B. Wilson. 2001. Cutting edge: functional interactions between toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR1 or TLR6 in response to phenol-soluble modulin. J. Immunol. 166:15-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han, J., J. D. Lee, L. Bibbs, and R. J. Ulevitch. 1994. A MAP kinase targeted by endotoxin and hyperosmolarity in mammalian cells. Science 265:808-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashimoto, S., Y. Gon, K. Matsumoto, S. Maruoka, I. Takeshita, S. Hayashi, Y. Asai, I. Jibiki, T. Machino, and T. Horie. 2000. Selective inhibitor of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-8 expression in human pulmonary vascular endothelial cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 293:370-375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heine, H., C. J. Kirschning, E. Lien, B. G. Monks, M. Rothe, and D. T. Golenbock. 1999. Cutting edge: cells that carry A null allele for toll-like receptor 2 are capable of responding to endotoxin. J. Immunol. 162:6971-6975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hippenstiel, S., S. Soeth, B. Kellas, O. Fuhrmann, J. Seybold, M. Krull, C. Eichel-Streiber, M. Goebeler, S. Ludwig, and N. Suttorp. 2000. Rho proteins and the p38-MAPK pathway are important mediators for LPS-induced interleukin-8 expression in human endothelial cells. Blood 95:3044-3051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirschfeld, M., J. J. Weis, V. Toshchakov, C. A. Salkowski, M. J. Cody, D. C. Ward, N. Qureshi, S. M. Michalek, and S. N. Vogel. 2001. Signaling by toll-like receptor 2 and 4 agonists results in differential gene expression in murine macrophages. Infect. Immun. 69:1477-1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Janeway, C. A., Jr. 1992. The immune system evolved to discriminate infectious nonself from noninfectious self. Immunol. Today 13:11-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kopp, E. B., and R. Medzhitov. 1999. The Toll-receptor family and control of innate immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 11:13-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumada, H., Y. Haishima, T. Umemoto, and K. Tanamoto. 1995. Structural study on the free lipid A isolated from lipopolysaccharide of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Bacteriol. 177:2098-2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lien, E., T. K. Means, H. Heine, A. Yoshimura, S. Kusumoto, K. Fukase, M. J. Fenton, M. Oikawa, N. Qureshi, B. Monks, R. W. Finberg, R. R. Ingalls, and D. T. Golenbock. 2000. Toll-like receptor 4 imparts ligand-specific recognition of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J. Clin. Investig. 105:497-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Madianos, P. N., P. N. Papapanou, and J. Sandros. 1997. Porphyromonas gingivalis infection of oral epithelium inhibits neutrophil transepithelial migration. Infect. Immun. 65:3983-3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mattsby-Baltzer, I., Z. Mielniczuk, L. Larsson, K. Lindgren, and S. Goodwin. 1992. Lipid A in Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 60:4383-4387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCoy, S. A., H. R. Creamer, M. Kawanami, and D. F. Adams. 1987. The concentration of lipopolysaccharide on individual root surfaces at varying times following in vivo root planing. J. Periodontol. 58:393-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Medzhitov, R., and C. A. Janeway, Jr. 1998. An ancient system of host defense. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 10:12-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore, J., M. Wilson, and J. B. Kieser. 1986. The distribution of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (endotoxin) in relation to periodontally involved root surfaces. J. Clin. Periodontol. 13:748-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muotiala, A., I. M. Helander, L. Pyhala, T. U. Kosunen, and A. P. Moran. 1992. Low biological activity of Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 60:1714-1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nick, J. A., N. J. Avdi, S. K. Young, L. A. Lehman, P. P. McDonald, S. C. Frasch, M. A. Billstrom, P. M. Henson, G. L. Johnson, and G. S. Worthen. 1999. Selective activation and functional significance of p38alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated neutrophils. J. Clin. Investig. 103:851-858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ogawa, T. 1993. Chemical structure of lipid A from Porphyromonas (Bacteroides) gingivalis lipopolysaccharide. FEBS Lett. 332:197-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogawa, T., and H. Uchida. 1996. Differential induction of IL-1 beta and IL-6 production by the nontoxic lipid A from Porphyromonas gingivalis in comparison with synthetic Escherichia coli lipid A in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 14:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ogawa, T., H. Uchida, and K. Amino. 1994. Immunobiological activities of chemically defined lipid A from lipopolysaccharides of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Microbiology 140:1209-1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pelech, S. L., and J. S. Sanghera. 1992. MAP kinases: charting the regulatory pathways. Science 257:1355-1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peterson, A. A., A. Haug, and E. J. McGroarty. 1986. Physical properties of short- and long-O-antigen-containing fractions of lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli O111:B4. J. Bacteriol. 165:116-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poltorak, A., P. Ricciardi-Castagnoli, S. Citterio, and B. Beutler. 2000. Physical contact between lipopolysaccharide and toll-like receptor 4 revealed by genetic complementation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:2163-2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pugin, J., C.-C. Schurer-Maly, D. Leturcq, A. Moriarty, J. Ulevitchr, and P. S. Tobias. 1993. Lipopolysaccharide activation of human endothelial and epithelial cells is mediated by lipopolysaccharide-binding protein and soluble CD14. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:2744-2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qureshi, N., I. Kaltashov, K. Walker, V. Doroshenko, R. J. Cotter, K. Takayama, T. R. Sievert, P. A. Rice, J. S. Lin, and D. T. Golenbock. 1997. Structure of the monophosphoryl lipid A moiety obtained from the lipopolysaccharide of Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Biol. Chem. 272:10594-10600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reife, R. A., R. A. Shapiro, B. A. Bamber, K. K. Berry, G. E. Mick, and R. P. Darveau. 1995. Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide is poorly recognized by molecular components of innate host defense in a mouse model of early inflammation. Infect. Immun. 63:4686-4694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schroder, N. W., D. Pfeil, B. Opitz, K. S. Michelsen, J. Amberger, U. Zahringer, U. B. Gobel, and R. R. Schumann. 2001. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases p42/44, p38, and stress-activated protein kinases in myelo-monocytic cells by Treponema lipoteichoic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 276:9713-9719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schumann, R. R., D. Pfeil, N. Lamping, C. Kirschning, G. Scherzinger, P. Schlag, L. Karawajew, and F. Herrmann. 1996. Lipopolysaccharide induces the rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of the mitogen-activated protein kinases erk-1 and p38 in cultured human vascular endothelial cells requiring the presence of soluble CD14. Blood 87:2805-2814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwartz, J., F. L. Stinson, and R. B. Parker. 1972. The passage of tritiated bacterial endotoxin across intact gingival crevicular epithelium. J. Periodontol. 43:270-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shapira, L., S. Takashiba, S. Amar, and T. E. Van Dyke. 1994. Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide stimulation of human monocytes: dependence on serum and CD14 receptor. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 9:112-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shapiro, R. A., M. D. Cunningham, K. Ratcliffe, C. Seachord, J. Blake, J. Bajorath, A. Aruffo, and R. P. Darveau. 1997. Identification of CD14 residues involved in specific lipopolysaccharide recognition. Infect. Immun. 65:293-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Socransky, S. S., and A. D. Haffajee. 1992. The bacterial etiology of destructive periodontal disease: current concepts. J. Periodontol. 63:322-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Strittmatter, W., J. Weckesser, P. V. Salimath, and C. Galanos. 1983. Nontoxic lipopolysaccharide from Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides ATCC 17023. J. Bacteriol. 155:153-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tabeta, K., K. Yamazaki, S. Akashi, K. Miyake, H. Kumada, T. Umemoto, and H. Yoshie. 2000. Toll-like receptors confer responsiveness to lipopolysaccharide from Porphyromonas gingivalis in human gingival fibroblasts. Infect. Immun. 68:3731-3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tamura, D. Y., E. E. Moore, J. L. Johnson, G. Zallen, J. Aiboshi, and C. C. Silliman. 1998. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibition attenuates intercellular adhesion molecule-1 up-regulation on human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. Surgery 124:403-408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tanamoto, K., S. Azumi, Y. Haishima, H. Kumada, and T. Umemoto. 1997. Endotoxic properties of free lipid A from Porphyromonas gingivalis. Microbiology 143:63-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tonetti, M. S., M. A. Imboden, and N. P. Lang. 1998. Neutrophil migration into the gingival sulcus is associated with transepithelial gradients of interleukin-8 and ICAM-1. J. Periodontol. 69:1139-1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ulevitch, R. J., and P. S. Tobias. 1999. Recognition of gram-negative bacteria and endotoxin by the innate immune system. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 11:19-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Viriyakosol, S., J. C. Mathison, P. S. Tobias, and T. N. Kirkland. 2000. Structure-function analysis of CD14 as a soluble receptor for lipopolysaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 275:3144-3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wilkinson, S. G. 1983. Composition and structure of lipopolysaccharides from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Rev. Infect. Dis. 5(Suppl.):S941-S949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wright, S. D. 1995. CD14 and innate recognition of bacteria. J. Immunol. 155:6-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wyllie, D. H., E. Kiss-Toth, A. Visintin, S. C. Smith, S. Boussouf, D. M. Segal, G. W. Duff, and S. K. Dower. 2000. Evidence for an accessory protein function for the Toll-like receptor TLR1 in lipopolysaccharide responses. J. Immunol. 165:7125-7132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]