Abstract

More effective vaccines against Mycobacterium tuberculosis may contribute to the control of this major human pathogen. DNA vaccines encoding single mycobacterial proteins stimulate antimycobacterial T-cell responses and induce partial protection against M. tuberculosis in animal models. The protective efficacy of these vaccines encoding a single antigen, however, has been less than that afforded by the current vaccine, Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG). The heterodimeric cytokine interleukin-12 (IL-12) potentiates the induction and maintenance of the type 1 helper T-cell response. We have developed a novel self-splicing vector based on the 2A protein of foot-and-mouth disease virus that permits the coordinate expression of both chains of IL-12 (p2AIL12). Coimmunization with this vector and DNA expressing M. tuberculosis antigen 85B or MPT64 enhanced the specific lymphocyte proliferative response and increased the frequency of specific gamma interferon-secreting T cells against the whole protein and a defined CD8+ T-cell epitope on MPT64. Further, coimmunizing with p2AIL12 significantly increased the protective efficacy of DNA-85 in the lung against an aerosol challenge with M. tuberculosis to the level achieved with BCG. Therefore, codelivery of an IL-12-secreting plasmid may be a potent strategy for enhancing the protective efficacy of vaccines against M. tuberculosis.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis continues to be one of the foremost causes of human mortality by a single pathogen. Although the presently available vaccine, bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis, is widely used, it has had little impact on the prevalence of tuberculosis (TB) (17). The emergence of multidrug-resistant strains and the increasing incidence rate of TB in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) have emphasized the importance of developing new anti-TB vaccines. One approach is to use subunit vaccines containing dominant antigens in the host response to M. tuberculosis. Vaccines based on culture filtrate proteins of M. tuberculosis have been found to induce protective immunity in mice (26) and guinea pigs (4). A recent strategy for delivering such protective antigens has been by DNA immunization. DNA vaccines not only induce mycobacterium-specific CD4+ T lymphocytes that secrete gamma interferon (IFN-γ) but also stimulate antigen-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T cells which may enhance the protective effect (45). Several studies have established that DNA vaccines encoding mycobacterial antigens stimulated antimycobacterial immune responses and partial protection against M. tuberculosis infection (27, 30, 45). The level of protection has been variable, and generally DNA expressing a single protein has not been as effective as BCG. Immunization with plasmids expressing a combination of antigens has been more efficient (30). Several strategies to increase the effectiveness of DNA vaccines have been investigated, including codelivery of genes encoding cytokines (33).

Acquired cellular immunity to M. tuberculosis is critically dependent on CD4+ T cells that secrete IFN-γ (14), and protective immunity is associated with the development of a strong Th1 T-cell response. The development of Th1-like CD4+ cells from uncommitted T cells recognizing defined antigens is induced by the cytokine interleukin-12 (IL-12). IL-12 is a heterodimeric cytokine comprising p35 and p40 chains. It is produced mainly by macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), and B cells (35, 46). It has potent effects on the activation of NK cells and the maturation of CD8+ as well as CD4+ T cells (43, 48). The importance of IL-12 and the development of a Th1 T-cell response for protection against mycobacterial infections is exemplified by the increased susceptibility of both mice with genes deleted and humans with genetic deficiencies in IL-12 signaling. Mice deficient in the p40 chain of IL-12 demonstrate increased susceptibility to M. tuberculosis infection (9), and administration of exogenous recombinant IL-12 (rIL-12) during M. tuberculosis infection increased resistance in both normal and immunocompromised mice (19). Humans with deficiency in the β1 chain of the IL-12 receptor are susceptible to Mycobacterium avium, BCG, and other intracellular parasites (10). More recently, Lowrie and colleagues demonstrated that administration of IL-12 DNA was an effective immunotherapy to boost the efficiency of the immune system to clear the M. tuberculosis (37). Codelivery of vector-encoded IL-12 enhanced the antigen-specific T-cell response to a variety of other infectious agents following DNA immunization, including HIV (47), influenza virus (28), and herpes simplex virus (44). Therefore, we hypothesized that coimmunizing with plasmid IL-12 may enhance the protective efficacy of DNA vaccines against TB.

For the secretion of biologically active IL-12, both the p35 and p40 chains must be coexpressed (22). A strategy was developed for the dual expression of the two polypeptides by one plasmid through the use of a component of the 2A protein of foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) (7). Coimmunizing with this IL-12-expressing vector and DNA vaccines expressing secreted proteins of M. tuberculosis increased the specific IFN-γ T-cell response. When immunized mice were challenged with aerosol M. tuberculosis, there was significant enhancement of the protective efficacy in mice coimmunized with this IL-12 vector. Furthermore, mice immunized with BCG and this novel vector also demonstrated increased protection against M. tuberculosis infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

M. tuberculosis H37Rv (ATCC 27294) was grown in Proskauer and Beck liquid medium for 14 days, and M. bovis (CSL strain), derived from BCG Glaxo, was grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth supplemented with albumin-dextrose-catalase (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) for 14 days at 37°C. The bacteria were enumerated on oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase-enriched Middlebrook 7H11 agar and stored in 30% glycerol-phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at −70°C. For plasmid preparations, Escherichia coli MC1061 was grown in Luria-Bertani broth or agar supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml), and for large-scale preparations, the transformed bacteria were grown in Circlegrow broth (BIO 101, Vista, Calif.) with ampicillin.

Production of DNA vaccines, protein antigens, and peptides.

The genes for MPT64 and antigen 85B were amplified from the genome DNA from M. tuberculosis H37Rv and cloned into pJW4303 downstream of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early promoter to yield plasmids DNA-64 and DNA-85, respectively (30). The murine IL-12p35 and IL-12p40 genes were amplified from the vectors pED.IL-12p35 and pED.IL-12p40, respectively, which were kindly provided by the Genetics Institute Inc. (Cambridge, Mass.). These were inserted into the pCI2A vector (7), which contains the sequence for the splicing peptide of 2A FMDV protein and the CMV promoter. pcDNA3 was used as the control vector, as it is related to the pCI2A vector backbone (pCI-neo). The p35 gene was upstream of the 2A motif, while the p40 gene was downstream of the motif. DNAs for immunizations were prepared by CsCl centrifugation and stored in PBS at −20°C. MPT64 protein was expressed and purified as described previously (30), and antigen 85 protein was obtained through the TB Research Material and Vaccine Testing Contract, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (No1 AI-75320). The peptide 12, FAVTNDGVI, an H-2Db-restricted T-cell epitope from MPT64 (15), and the peptide ASNENMDAM, an H-2b-restricted epitope from nucleoprotein of influenza virus, were obtained from Chiron Mimotopes (Melbourne, Australia) and used at a concentration of 2 μg/ml.

Production of rIL-12.

rIL-12 was prepared by expressing the p35 and p40 chains of IL-12 in baculovirus (BaculoGold DNA; PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.) and infecting Sf21 insect cells. The concentration of rIL-12 in supernatants was measured in a biological assay (42).

Animals and immunization.

Six- to 8-week old C57BL/6 female mice were obtained from Animal Resources Centre (Perth, Australia) and maintained in specific-pathogen-free conditions. Mice were immunized twice at 2-week intervals with 100 μg of DNA-64 or DNA-85 mixed with either 100 μg of p2AIL12 or 100 μg of control vector (pJW4303) by intramuscular injection into each tibialis anterior muscle. Control mice were immunized with 200 μg of parental vector pJW4303. Mice immunized with DNA-64 and rIL-12 received 400 μg of rIL-12 by intraperitoneal injection at the time of DNA-64 immunization, and this was repeated 2 weeks later. Control mice were immunized with BCG (105 CFU) by subcutaneous injections more than 100 days prior to challenge. We examined the effectiveness of plasmid IL-12 with BCG immunization by delivery of the 100 μg of p2AIL12 plasmid at the time of BCG immunization. For prime boost experiments mice were immunized with 100 μg of DNA-85 plus 100 μg of plasmid IL-12 or 100 μg of control vector, and 2 weeks later the mice were boosted with BCG (105 CFU) subcutaneously.

Mycobacterial challenge.

Six weeks after the last boost with DNA vaccine or BCG for the prime boost experiment, mice were challenged with aerosol M. tuberculosis H37Rv by using a Middlebrook airborne-infection apparatus (Glas-Col, Terre Haute, Ind.) with an infective dose of approximately 100 viable bacilli per lung. Four weeks after the challenge, the number of bacteria in one lung was enumerated by homogenizing the tissue and plating 10-fold dilutions on supplemented Middlebrook 7H11 Bacto agar.

Transfection of HEK 293 cells.

Six-well plates were seeded with 4 × 105 human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells overnight. A mixture of plasmid DNA and FuGene (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions and then added to HEK 293 cells. After 48 h, the supernatant and cells were collected separately. Lysates of the cells were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose for immunoblotting with the anti-IL-12p40 monoclonal antibody C15.6. The levels of secreted IL-12 in the supernatants were determined by IL-12 bioassay.

IL-12 bioassay.

The bioassay depends on up-regulation of the IL-12 receptor on concanavalin A (ConA) (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.)-activated lymphoblast cells treated with IL-2 and the subsequent dose-dependent proliferation of these lymphoblasts in response to IL-12. The assay was performed as previously described (42). Splenocytes from normal C57BL/6 mice were resuspended in complete RPMI supplemented with 2 mM glutamate, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, and 10% fetal calf serum and activated with the mitogen ConA (2 μg/ml) for 3 days, and IL-2 (20 U/ml) was added and left for an additional day. Meanwhile, 96-well plates were coated with anti-IL-12p40 antibody (C15.6) at 20 μg/ml in 0.1 carbonate buffer (pH 9.5) overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2. The plates were then washed three times, blocked with 5% fetal calf serum-PBS at 37°C for 1 h, and washed three times. Serial dilutions of supernatants from the transfections and murine rIL-12 (PharMingen) standards (3 pg/ml to 100 ng/ml) were added to the plates. The activated splenocytes (5 × 104/well) were then added to the plates and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Cells were pulsed with [3H]thymidine (50 μCi/well; NEN Life Sciences, Boston, Mass.) for 16 h, and incorporation of [3H]thymidine was determined. From the linear part of the standard curve, the amount of bioactive IL-12 was determined.

Antibody measurement.

Antigen-specific antibody levels in sera were detected by ELISA as described previously (30). Briefly, the wells were coated with MPT64 (10 μg/ml) or antigen 85 complex (2 μg/ml), and fivefold dilutions of mouse sera were incubated for 1 h prior to the addition of goat anti-murine immunoglobulin G (IgG) alkaline phosphate-conjugated antibodies (1:2,000) (Sigma) and then n-nitrophenyl-phosphate (1 mg/ml) (Sigma). The mean absorbance of normal mouse sera, diluted at 1:100, plus three standard deviations was adopted as the cutoff absorbance for determining antibody titers, which are shown as the geometric mean of the log10 titer.

Lymphocyte proliferation.

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from the splenocytes of immunized mice in complete RPMI medium and tested individually. T cells were enriched by passing leukocytes through nylon wool. Semipurified T cells and gamma-irradiated syngeneic splenocytes as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) (2 × 105 cells each) were added to 96-well plates and incubated with various concentrations of MPT64, ConA, or medium alone for 72 h. They were then pulsed with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine per well for 6 h, and the specific incorporation of [3H]thymidine was determined.

ELIspot for cytokine-producing cells.

The anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody AN18 (Endogen, Woburn, Mass.) was applied to the nitrocellulose wells of an Immobilon-P plate (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.). Splenocytes from immunized mice were added to the plate at 2 × 105, 4 × 104, and 8 × 103 cells per well and incubated with antigen 85 complex (2 μg/ml), MPT64 (5 μg/ml), the peptides (2 μg/ml), ConA (2 μg/ml), and medium alone. Following 16 h of incubation at 37°C, the plates were washed and incubated with biotinylated anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody XMG 1.2 (Endogen) for 1 h. They were then washed three times before the addition of streptavidin-alkaline phosphate conjugate. The presence of IFN-γ-producing cells was visualized by use of the AP Conjugate Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.), and the spots were counted at a magnification of ×5.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis of the results from immunological assays and log-transformed bacterial counts were conducted using analysis of variance. Fisher's protected least-significant difference analysis of variance post hoc test was used for pairwise comparison of multigrouped data sets. Differences with P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

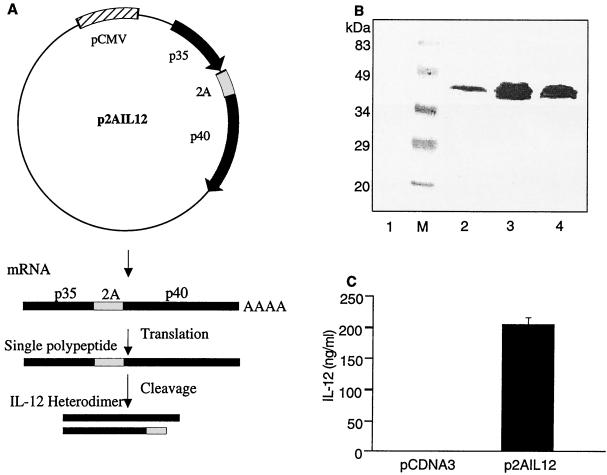

Expression of IL-12 by transfected HEK 293 cells.

The two chains of IL-12 were cloned on either side of the 2A site in the pCI2A vector downstream of the CMV promoter to yield plasmid p2AIL12 (Fig. 1A). This permitted the coordinate expression of both chains of IL-12 by transfected cells. HEK 293 cells were transiently transfected with two clones of p2AIL12. Following sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under reducing conditions, a band of approximately 40 kDa was detected with anti-IL-12p40 monoclonal antibody (C15.6) in lysates of cells transfected with p2AIL12 but not in those transfected with the control vector (Fig. 1B). Biologically active IL-12 requires the expression of both the p35 and p40 chains (42). Therefore, we assessed the activity of IL-12 by using a bioassay with mitogen-stimulated lymphoblasts (42). Biologically active IL-12 was found only in the supernatant of p2AIL12-transfected cells, confirming the expression of both chains (Fig. 1C). The highest-yielding clone, termed p2AIL12, was used for further studies.

FIG. 1.

Expression of functional IL-12 by p2AIL12 vector. (A) The p35 and p40 genes of IL-12 were cloned into the pCI2A vector, under the control of the CMV promoter, on either side of the FMDV virus 2A site. This episomal plasmid transcribes a single mRNA, which is translated into a single polypeptide. The 2A sequence is then cleaved at the C-terminal end to form the heterodimeric IL-12. (B) Using anti-IL-12p40 antibody C15.6, the p40 chain of IL-12 was detected in cells transfected with two different clones of p2AIL12 (lanes 2 and 3) or in the lane containing recombinant murine IL-12 (lane 4) but not in cells transfected with pCDNA-3 (control vector) (lane1). Lane M, molecular mass standards. (C) Biologically active IL-12 was detected by an IL-12 bioassay in the supernatant of cells transfected with the selected clone of p2AIL12 but not cells transfected with the control vector. The error bar indicates the standard deviation.

Coimmunization with p2AIL12 increases the antigen-specific T-cell response to DNA vaccines.

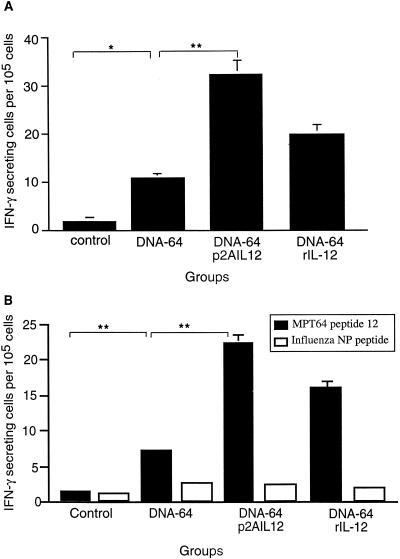

Immunization with DNA-64 and p2AIL12 on two occasions increased the antigen-specific proliferative response to MPT64 (Table 1). This was comparable to the effect of cotreatment of DNA-64-immunized mice with rIL-12. Coimmunizing with DNA-64 or DNA-85 and p2AIL12 also stimulated an antigen-specific IFN-γ response on recall to MPT64 (Fig. 2A) or to antigen 85 protein (Fig. 3) , respectively. To determine the effect of IL-12 on the CD8+ T-cell response, splenocytes from mice coimmunized with DNA-64 and p2AIL12 or rIL-12 were restimulated with a H-2Db-restricted epitope of MPT64 (FAVTNDGVI) or an irrelevant H-2b peptide from influenza virus nucleoprotein. Coimmunizing with p2AIL12 significantly increased the IFN-γ response to this CD8+ T-cell epitope from MPT64 (Fig. 2B).

TABLE 1.

Codelivery of plasmid IL-12 and rIL-12 enhances the antigen-specific proliferative response stimulated by DNA-64a

| Vaccine group | Δcpmb |

|---|---|

| Control vector | 932 ± 248 |

| DNA-64 | 3,720 ± 405 |

| DNA-64 + p2AIL12 | 11,968 ± 540** |

| DNA-64 + rIL-12 | 9,208 ± 640** |

Mice were immunized twice with 100 μg of DNA-64 with either p2AIL12 (100 μg) or rIL-12 (400 μg) or twice with 200 μg of control vector. Two weeks after the last injection, the proliferative response of splenic lymphocytes to MPT64 (10 μg/ml) was determined by specific [3H]thymidine incorporation.

Data represent the means and standard errors of the means for five mice and are representative of two separate experiments. **, P < 0.001.

FIG. 2.

Codelivery of p2AIL12 increases the frequency of MPT64-specific IFN-γ-producing cells following immunization with DNA-64. Mice were immunized twice intramuscularly at 2-week intervals with control vector (200 μg) or DNA-64 (100 μg) combined with either control vector (100 μg), p2AIL12 (100 μg), or rIL-12 (400 μg) administered intraperitoneally. Six weeks after the second immunization, splenocytes were harvested and incubated with MPT64 protein (A) or the major histocompatibility complex class I-binding peptide 12 or an irrelevant influenza virus nucleoprotein (NP) peptide (B). Data are the means and standard deviations for five mice from one of two separate experiments. The significances of the differences between DNA-64 and DNA-64 with IL-12 treatment were P < 0.005 for protein (∗∗) and P < 0.003 for peptide (∗∗).

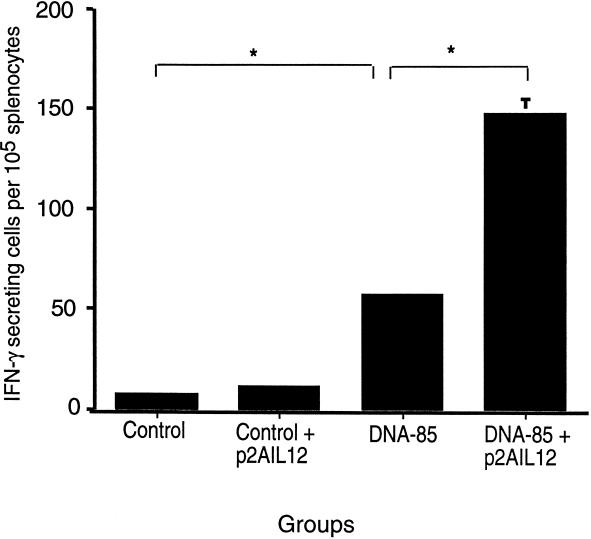

FIG. 3.

Codelivery of p2AIL12 increases the frequency of IFN-γ-producing cells following immunization with DNA-85. Mice were immunized twice intramuscularly at 2-week intervals with control vector alone (200 μg), control vector combined with p2AIL12 (100 μg), DNA-85 (100 μg), or DNA-85 (100 μg) combined with p2AIL12 (100 μg). Six weeks after the second immunization, splenocytes were harvested and stimulated with antigen 85 complex. The number of IFN-γ-secreting cells in response to antigen 85 was measured by ELIspot. Data are the means and standard deviationsfor five mice from one of two separate experiments. ∗, P < 0.005 for the differences between DNA-85 and DNA-85 with p2AIL12.

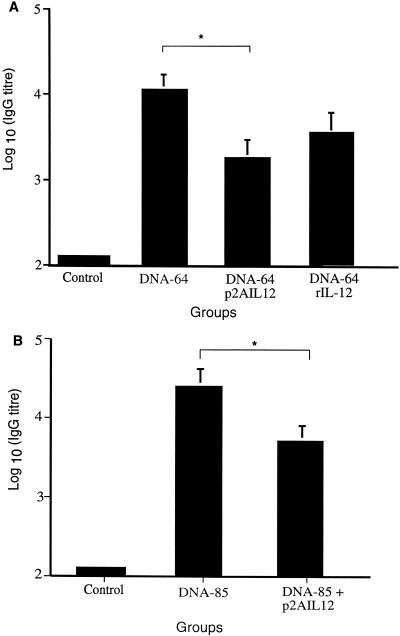

Coimmunization with p2AIL12 decreases the antigen-specific antibody response to DNA vaccines.

To determine whether codelivery of the IL-12 vector with DNA-64 and DNA-85 influenced the antibody responses to the encoded antigens, sera were collected at 4 to 6 weeks following the last immunization and tested by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Mice immunized with DNA-64 or DNA-85 generated anti-MPT64 and anti-85B antibodies (Fig. 4). Coimmunizing with p2AIL12 resulted in a small, but significant, reduction in anti-MPT64 (Fig. 4A) and anti-antigen 85 (Fig. 4B) IgG titers.

FIG. 4.

Coimmunization with p2AIL12 decreases the antigen-specific antibody response. Mice were immunized as described in the legends for Fig. 2 and 3. Six weeks after the second immunization, sera were collected from mice immunized with combinations of p2AIL12 and DNA-64 (A) or DNA-85 (B). The geometric means of the log10 titers of anti-MPT64 (A) and anti-antigen 85B (B) IgG antibodies were measured as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent the means and standard deviations for five mice from one of two separate experiments. The results shown utilized sera from the same mice used for the experiments in Fig. 2 and 3. ∗, P < 0.05 for the difference between the groups.

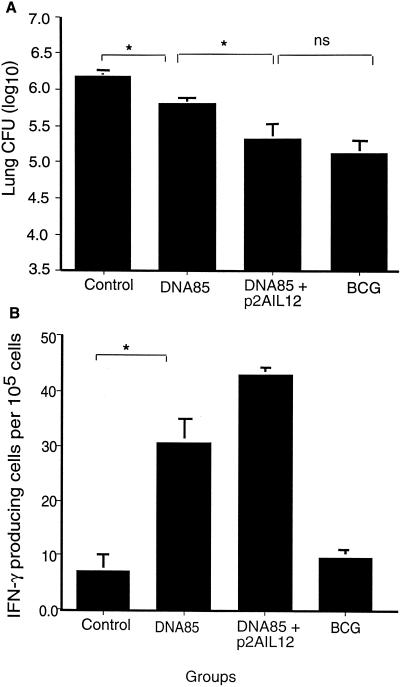

Coimmunization with p2AIL12 increases the protective efficacy of DNA vaccines.

In order to examine the effect of coimmunization with plasmid IL-12 on the protective efficacy of the DNA-85 vaccine, mice immunized twice with DNA-85 and p2AIL12 were challenged 6 weeks later with aerosol M. tuberculosis H37Rv. Four weeks later, the bacterial load in the lungs was analyzed. Immunization with DNA-85B resulted in a significant reduction in the bacterial load in the lungs (Fig. 5A). Coimmunization with the p2AIL12 led to a further significant reduction in the number of M. tuberculosis organisms in the lung. There was no significant difference between the bacterial loads in mice immunized with BCG and mice immunized with DNA-85B and p2AIL12. In order to determine whether enhanced protection was associated with increased IFN-γ production at the peak of infection, the frequency of IFN-γ-producing cells was enumerated by ELIspot. Following coimmunization with the plasmid IL-12, there was an increase in the number of antigen-specific IFN-γ-secreting cells in the mediastinal lymph nodes, draining the lungs (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Coimmunization with p2AIL12 increases the protective efficacy of DNA-85 against aerosol infection with M. tuberculosis. Mice were immunized twice intramuscularly at 2-week intervals with control vector alone (200 μg) or combined with DNA-85 (100 μg), with DNA-85 (100 μg) combined with p2AIL12 (100 μg), or with subcutaneous BCG (105 CFU). Six weeks after the last immunization, mice were challenged with aerosol M. tuberculosis H37Rv. Four weeks later, the bacterial load in the lungs and the antigen-specific IFN-γ production in the draining lymph nodes were analyzed. Data are the means and standard deviations for five mice from one of four separate experiments for the bacterial load (A) and the antigen 85-specific IFN-γ-secreting cells in the draining mediastinal lymph nodes (B). The significances of differences between the groups were analyzed by analysis of variance (∗, P < 0.05; ns, not significant).

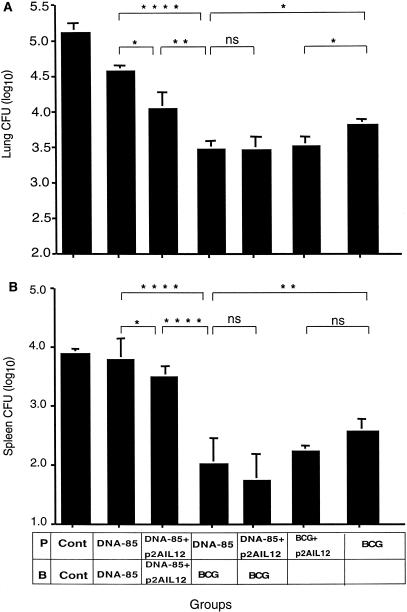

Sequential immunization with DNA-85, p2AIL12, and BCG.

We have recently demonstrated that priming with DNA-85 and boosting with BCG increases the protective efficacy of BCG (16). Therefore, we examined whether priming with DNA-85 and p2AIL12 prior to BCG would further increase the protective effect. Mice were immunized with DNA-85 with and without p2AIL12 and 2 weeks later were boosted with BCG. Six weeks after the boost, mice were challenged with aerosol M. tuberculosis. Priming with DNA-85 and boosting with BCG resulted in a greater degree of protection in the lungs than that afforded by DNA-85 (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 6A), and this effect was even more apparent in the spleen (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 6B). This combination was significantly more protective than BCG alone in the lungs (P < 0.05) and spleen (P < 0.01). The prime boost combination of DNA-85 and BCG was also more protective than the addition of p2AIL12 to DNA-85 (lung, P < 0.0001; spleen, P < 0.0001). The combination of p2AIL12 and DNA-85 for priming before BCG, however, did not increase the protective efficacy further than that obtained by priming with DNA-85 alone (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Sequential immunization with DNA-85, p2AIL12, and BCG. Groups of mice were primed (P) and boosted (B) with combinations of control vector (Cont) (200 μg), DNA-85 (100 μg), p2AIL12 (100 μg), and BCG (105 CFU) as indicated. Six weeks after the boost, mice were challenged with aerosol M. tuberculosis. Four weeks after infection the bacterial loads in the lungs (A) and spleens (B) were analyzed. Data represent the means and standard deviations for five mice from one of two separate experiments. The significances of the differences between the groups were analyzed by analysis of variance (∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01; ∗∗∗, P < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗, P < 0.00001; ns, not significant.

Coimmunization with p2AIL12 increases the protective efficacy of BCG.

To examine the effect of codelivery of a plasmid expressing IL-12 with BCG, mice were immunized with p2AIL12 intramuscularly at the time of BCG immunization. This resulted in significantly greater protective efficacy than that afforded by BCG alone in the lung (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6A) but not in the spleen (Fig. 6B).

DISCUSSION

The genome of M. tuberculosis contains over 3,900 genes (8), and multiple mycobacterial proteins stimulate lymphocyte response in infected subjects (40). Despite the complexity of the host response to M. tuberculosis, immunization with a restricted cohort of these antigens, either as proteins (4, 26) or as DNA vaccines (27, 30, 45, 49), can stimulate partial protection against experimental TB in small animals. This raises the prospect of effective subunit vaccines against TB; however, it will be necessary to increase this effect in order to translate their potential into candidate vaccines for humans. Strategies to increase the protective efficacy of DNA vaccines include manipulating the cytokine milieu by codelivery of genes encoding cytokines (33) and targeting of antigens to APCs (5). We have utilized a novel self-cleaving vector, derived from the FMDV 2A proteins (7), to develop a vector which expresses both chains of murine IL-12 in the same cells, leading to the secretion of bioactive IL-12 (Fig. 1). This overcomes the potential problem of p40 homodimers produced from plasmids expressing IL-12p40 alone inhibiting the signaling of the IL-12 heterodimer through the IL-12 receptor (24). Coimmunizing with this IL-12-expressing plasmid and DNA vaccines expressing the different mycobacterial secreted proteins increased the lymphocyte proliferative response (Table 1) and the frequency of antigen-specific T-cell responses to the proteins (Fig. 2 and 3). Interestingly, coimmunization with IL-12 reduced the IgG antibody response to mycobacterial antigens encoded by these and other DNA vaccines (Fig. 4 and unpublished observation). This codelivery of IL-12 enhanced the protective efficacy of DNA-85 against M. tuberculosis infection in the lung to a level comparable to that obtained with BCG (Fig. 5).

The cytokine IL-12 is critical for the induction of Th1-like T cells (43). Infection of DCs (11, 25) and macrophages (18) with M. tuberculosis or M. bovis leads to the rapid secretion of IL-12. Costimulation of mycobacterium-infected DCs through CD40 enhances the IL-12 production and the activation of IFN-γ-secreting T cells (12). The frequency of IL-12-secreting cells in the peripheral blood is significantly increased during TB infection in humans (39). The importance of endogenous IL-12 in immunity to mycobacteria is confirmed by the increased susceptibility of subjects with deficiency in the IL-12β receptor (10) and of IL-12p40-deficient mice (9) to M. tuberculosis and other mycobacterial infections. The additive effect of IL-12 on the immunogenicity of DNA vaccines may occur through two mechanisms. First, DCs may be transfected with the IL-12 vector at the site of immunization and, following migration to the draining lymph nodes, secrete increased levels of IL-12. Antigen presentation following DNA immunization occurs through hemopoeitic-derived APCs, probably DCs, transfected at the site of immunization (3, 6). Transfection of APCs with the genes for IL-12 ex vivo has increased their immunogenic potential (2), and immunization with p2AIL12 may mirror this effect in vivo. Second, muscle cells transfected with p2AIL12 may continue to secrete low doses of IL-12 for a prolonged period (21), and this could have a persistent adjuvant effect by increasing the number of APCs and/or the efficiency of APCs in the draining lymph node.

In addition to its effects on the induction of Th1-like CD4+ T cells, IL-12 activates NK cells and CD8+ T cells (48). The latter is illustrated by the increased frequency of MPT64-specific CD8+ T cells following coimmunization with DNA-64 and p2AIL12 (Fig. 2B). Previous studies on the adjuvant effect of plasmid IL-12 have utilized either the p40 chain or separate vectors expressing the p40 and p35 chains. Coimmunization with IL-12 has increased the lymphocyte responses to HIV (47), influenza virus (28), and herpes simplex virus (44) and enhanced protective immunity against influenza virus and herpes simplex virus. Interestingly, we and others (44) have observed a small but significant reduction in specific antibody responses following coimmunization with plasmid IL-12 (Fig. 4). The increased IFN-γ response to a DNA vaccine expressing a Leishmania antigen with plasmid IL-12 was not associated with an increased protective effect of the vaccine (23). In contrast, coimmunization with the p40 chain of IL-12 and the DNA for the Coccidioides immitis did induce significantly enhanced protection against this fungal infection (29). Therefore, despite a favorable effect on the T-cell profile of cytokine production, the adjuvant effect of IL-12 on protection must be tested for each pathogen.

Other cytokines may also increase the immunogenicity of DNA vaccines (33). Previously we observed that codelivery of plasmid granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor with DNA-85 increased the specific IFN-γ T-cell response to antigen 85B but did not improve the protective efficacy against M. tuberculosis (31). IL-18 is a separate macrophage-derived cytokine which has an additive effect on the development of Th1 T-cell responses by binding to IL-18 receptors induced by IL-12 (1). The optimal IFN-γ responses to BCG (36) and Mycobacterium leprae (34) are partly dependent on IL-18. Therefore, IL-18 may also have an adjuvant effect with antimycobacterial vaccines.

In addition to its effect on DNA vaccines, coimmunizing with p2AIL12 and BCG increased the protective efficacy of BCG against M. tuberculosis infection in the lung. This is consistent with the finding of Freidag and colleagues that recombinant IL-12 protein delivered with BCG enhanced the protective efficacy of BCG against M. tuberculosis (20). The combination of BCG with oligonucleotides containing CpG motifs had a similar effect, probably due to their stimulation of IL-12 production. Recently, treatment with plasmid IL-12 alone during M. tuberculosis infection was reported to increase clearance of the M. tuberculosis from the lung (37), and plasmid IL-18 had a similar effect on BCG infection in mice (36).

The present study confirms our recent observation (16) that priming with DNA-85 and boosting with BCG improves the protective efficacy of BCG in the lung and spleen (Fig. 6). Coimmunization with plasmid IL-12 and DNA-85 prior to BCG did not increase the protective effect of this combination further. The increased protection observed with the DNA-BCG prime-boost combination was partly dependent on CD8+ T cells (16). Prime-boost immunization with DNA and recombinant viral vaccines has been effective in increasing protection against rodent malaria (41) and HIV in primates (32). This approach has resulted in mixed success in the case of M. tuberculosis. The combination of DNA and vaccinia virus or modified vaccinia virus Ankara vaccines expressing antigen-85B (16) or MPT64 (13), respectively, did not improve protection against M. tuberculosis; however, recently the combination of DNA and modified vaccinia virus Ankara expressing a fusion protein of MPT63 and ESAT-6 was found to be more effective than either vaccine alone (38).

In summary, codelivery of IL-12 with DNA encoding a single immunodominant mycobacterial antigen was as effective as BCG in protecting against aerosol TB. Further exploration of different combinations of antigens and Th1-promoting cytokines may lead to more effective antimycobacterial vaccines.

Acknowledgments

Umaimainthan Palendira and Arun T. Kamath contributed equally to this work.

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. The support of the New South Wales Health Department through its research and development infrastructure grants program is gratefully acknowledged. U. Palendira, A. T. Kamath, E. Martin, and C. G. Feng are recipients of the Australian Postgraduate Award. U. Palendira and E. Martin were also supported by the Cooperative Research Center for Vaccine Technology.

We thank H. Briscoe and C. Demangel for helpful discussions.

Editor: R. N. Moore

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn, H. J., S. Maruo, M. Tomura, J. Mu, T. Hamaoka, K. Nakanishi, S. Clark, M. Kurimoto, H. Okamura, and H. Fujiwara. 1997. A mechanism underlying synergy between IL-12 and IFN-γ-inducing factor in enhanced production of IFN-γ. J. Immunol. 159:2125-2131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahuja, S. S., S. Mummidi, H. L. Malech, and S. K. Ahuja. 1998. Human dendritic cell (DC)-based anti-infective therapy: engineering DCs to secrete functional IFN-γ and IL-12. J. Immunol. 161:868-876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akbari, O., N. Panjwani, S. Garcia, R. Tascon, D. Lowrie, and B. Stockinger. 1999. DNA vaccination: transfection and activation of dendritic cells as key events for immunity. J. Exp. Med. 189:169-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen, P. 1994. Effective vaccination of mice against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection with a soluble mixture of secreted mycobacterial proteins. Infect. Immun. 62:2536-2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyle, J. S., J. L. Brady, and A. M. Lew. 1998. Enhanced responses to a DNA vaccine encoding a fusion antigen that is directed to sites of immune induction. Nature 392:408-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casares, S., K. Inaba, T. D. Brumeanu, R. M. Steinman, and C. A. Bona. 1997. Antigen presentation by dendritic cells after immunization with DNA encoding a major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted viral epitope. J. Exp. Med. 186:1481-1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaplin, P. J., E. B. Camon, B. Villarreal-Ramos, M. Flint, M. D. Ryan, and R. A. Collins. 1999. Production of interleukin-12 as a self-processing 2A polypeptide. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 19:235-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole, S. T., R. Brosch, J. Parkhill, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, S. V. Gordon, K. Eiglmeier, S. Gas, C. E. Barry, F. Tekaia, K. Badcock, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. Davies, K. Devlin, T. Feltwell, S. Gentles, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, and B. G. Barrell. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper, A. M., J. Magram, J. Ferrante, and I. M. Orme. 1997. Interleukin 12 (IL-12) is crucial to the development of protective immunity in mice intravenously infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 186:39-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Jong, R., F. Altare, I. A. Haagen, D. G. Elferink, T. Boer, P. J. van Breda Vriesman, P. J. Kabel, J. M. Draaisma, J. T. van Dissel, F. P. Kroon, J. L. Casanova, and T. H. Ottenhoff. 1998. Severe mycobacterial and Salmonella infections in interleukin-12 receptor-deficient patients. Science 280:1435-1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demangel, C., A. G. Bean, E. Martin, C. G. Feng, A. T. Kamath, and W. J. Britton. 1999. Protection against aerosol Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection using Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guérin infected dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:1972-1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demangel, C., U. Palendira, C. G. Feng, A. W. Heath, A. G. Bean, and W. J. Britton. 2001. Stimulation of dendritic cells via CD40 enhances immune responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Infect. Immun. 69:2456-2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng, C. G., T. M. Blanchard, G. L. Smith, A. V. S. Hill, and W. J. Britton. 2002. Induction of CD8+ T cell response to a secreted antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by an attenuated vaccinia virus. Immunol. Cell Biol. 79:569-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng, C. G., and W. J. Britton. 2000. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells mediate adoptive immunity to aerosol infection of Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guérin. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1846-1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng, C. G., C. Demangel, A. T. Kamath, M. Macdonald, and W. J. Britton. 2001. Dendritic cells infected with Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette Guerin activate CD8+ T cells with specificity for a novel mycobacterial epitope. Int. Immunol. 13:451-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng, C. G., U. Palendira, C. Demangel, J. M. Spratt, A. S. Malin, and W. J. Britton. 2001. Priming with DNA immunization augments protective efficacy of Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin against tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 69:4174-4176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fine, P. E. 1995. Variation in protection by BCG: implications of and for heterologous immunity. Lancet 346:1339-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flesch, I. E., J. H. Hess, S. Huang, M. Aguet, J. Rothe, H. Bluethmann, and S. H. Kaufmann. 1995. Early interleukin 12 production by macrophages in response to mycobacterial infection depends on interferon gamma and tumor necrosis factor alpha. J. Exp. Med. 181:1615-1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flynn, J. L., M. M. Goldstein, K. J. Triebold, J. Sypek, S. Wolf, and B. R. Bloom. 1995. IL-12 increases resistance of BALB/c mice to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Immunol. 155:2515-2524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freidag, B. L., G. B. Melton, F. Collins, D. M. Klinman, A. Cheever, L. Stobie, W. Suen, and R. A. Seder. 2000. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides and interleukin-12 improve the efficacy of Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination in mice challenged with M. tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 68:2948-2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu, T. M., J. B. Ulmer, M. J. Caulfield, R. R. Deck, A. Friedman, S. Wang, X. Liu, J. J. Donnelly, and M. A. Liu. 1997. Priming of cytotoxic T lymphocytes by DNA vaccines: requirement for professional antigen presenting cells and evidence for antigen transfer from myocytes. Mol. Med. 3:362-371. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gubler, U., A. O. Chua, D. S. Schoenhaut, C. M. Dwyer, W. McComas, R. Motyka, N. Nabavi, A. G. Wolitzky, P. M. Quinn, and P. C. Familletti. 1991. Coexpression of two distinct genes is required to generate secreted bioactive cytotoxic lymphocyte maturation factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:4143-4147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gurunathan, S., D. L. Sacks, D. R. Brown, S. L. Reiner, H. Charest, N. Glaichenhaus, and R. A. Seder. 1997. Vaccination with DNA encoding the immunodominant LACK parasite antigen confers protective immunity to mice infected with Leishmania major. J. Exp. Med. 186:1137-1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heinzel, F. P., A. M. Hujer, F. N. Ahmed, and R. M. Rerko. 1997. In vivo production and function of IL-12 p40 homodimers. J. Immunol. 158:4381-4388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson, R. A., S. C. Watkins, and J. L. Flynn. 1997. Activation of human dendritic cells following infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 159:635-643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hubbard, R. D., C. M. Flory, and F. M. Collins. 1992. Immunization of mice with mycobacterial culture filtrate proteins. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 87:94-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huygen, K., J. Content, O. Denis, D. L. Montgomery, A. M. Yawman, R. R. Deck, C. M. DeWitt, I. M. Orme, S. Baldwin, C. D'Souza, A. Drowart, E. Lozes, P. Vandenbussche, J. P. Van Vooren, M. A. Liu, and J. B. Ulmer. 1996. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a tuberculosis DNA vaccine. Nat. Med. 2:893-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iwasaki, A., B. J. Stiernholm, A. K. Chan, N. L. Berinstein, and B. H. Barber. 1997. Enhanced CTL responses mediated by plasmid DNA immunogens encoding costimulatory molecules and cytokines. J. Immunol. 158:4591-4601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang, C., D. M. Magee, and R. A. Cox. 1999. Coadministration of interleukin 12 expression vector with antigen 2 cDNA enhances induction of protective immunity against Coccidioides immitis. Infect. Immun. 67:5848-5853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamath, A. T., C. G. Feng, M. Macdonald, H. Briscoe, and W. J. Britton. 1999. Differential protective efficacy of DNA vaccines expressing secreted proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 67:1702-1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamath, A. T., T. Hanke, H. Briscoe, and W. J. Britton. 1999. Co-immunization with DNA vaccines expressing granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and mycobacterial secreted proteins enhances T-cell immunity, but not protective efficacy against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Immunology 96:511-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kent, S. J., A. Zhao, S. J. Best, J. D. Chandler, D. B. Boyle, and I. A. Ramshaw. 1998. Enhanced T-cell immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccine regimen consisting of consecutive priming with DNA and boosting with recombinant fowlpox virus. J. Virol. 72:10180-10188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim, J. J., N. N. Trivedi, L. K. Nottingham, L. Morrison, A. Tsai, Y. Hu, S. Mahalingam, K. Dang, L. Ahn, N. K. Doyle, D. M. Wilson, M. A. Chattergoon, A. A. Chalian, J. D. Boyer, M. G. Agadjanyan, and D. B. Weiner. 1998. Modulation of amplitude and direction of in vivo immune responses by co-administration of cytokine gene expression cassettes with DNA immunogens. Eur. J. Immunol. 28:1089-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kobayashi, K., M. Kai, M. Gidoh, N. Nakata, M. Endoh, R. P. Singh, T. Kasama, and H. Saito. 1998. The possible role of interleukin (IL)-12 and interferon-γ-inducing factor/IL-18 in protection against experimental Mycobacterium leprae infection in mice. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 88:226-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobayashi, M., L. Fitz, M. Ryan, R. M. Hewick, S. C. Clark, S. Chan, R. Loudon, F. Sherman, B. Perussia, and G. Trinchieri. 1989. Identification and purification of natural killer cell stimulatory factor (NKSF), a cytokine with multiple biologic effects on human lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 170:827-845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kremer, L., L. Dupre, I. Wolowczuk, and C. Locht. 1999. In vivo immunomodulation following intradermal injection with DNA encoding IL-18. J. Immunol. 163:3226-3231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lowrie, D. B., R. E. Tascon, V. L. Bonato, V. M. Lima, L. H. Faccioli, E. Stavropoulos, M. J. Colston, R. G. Hewinson, K. Moelling, and C. L. Silva. 1999. Therapy of tuberculosis in mice by DNA vaccination. Nature 400:269-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McShane, H., R. Brookes, S. C. Gilbert, and A. V. Hill. 2001. Enhanced immunogenicity of CD4+ T-cell responses and protective efficacy of a DNA-modified vaccinia virus Ankara prime-boost vaccination regimen for murine tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 69:681-686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munk, M. E., P. Mayer, P. Anding, K. Feldmann, and S. H. Kaufmann. 1996. Increased numbers of interleukin-12-producing cells in human tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 64:1078-1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orme, I. M., P. Andersen, and W. H. Boom. 1993. T cell response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 167:1481-1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schneider, J., S. C. Gilbert, T. J. Blanchard, T. Hanke, K. J. Robson, C. M. Hannan, M. Becker, R. Sinden, G. L. Smith, and A. V. Hill. 1998. Enhanced immunogenicity for CD8+ T cell induction and complete protective efficacy of malaria DNA vaccination by boosting with modified vaccinia virus Ankara. Nat. Med. 4:397-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schoenhaut, D. S., A. O. Chua, A. G. Wolitzky, P. M. Quinn, C. M. Dwyer, W. McComas, P. C. Familletti, M. K. Gately, and U. Gubler. 1992. Cloning and expression of murine IL-12. J. Immunol. 148:3433-3440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seder, R. A., R. Gazzinelli, A. Sher, and W. E. Paul. 1993. Interleukin 12 acts directly on CD4+ T cells to enhance priming for interferon gamma production and diminishes interleukin 4 inhibition of such priming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:10188-10192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sin, J. I., J. J. Kim, R. L. Arnold, K. E. Shroff, D. McCallus, C. Pachuk, S. P. McElhiney, M. W. Wolf, S. J. Pompa-de Bruin, T. J. Higgins, R. B. Ciccarelli, and D. B. Weiner. 1999. IL-12 gene as a DNA vaccine adjuvant in a herpes mouse model: IL-12 enhances Th1-type CD4+ T cell-mediated protective immunity against herpes simplex virus-2 challenge. J. Immunol. 162:2912-2921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tascon, R. E., M. J. Colston, S. Ragno, E. Stavropoulos, D. Gregory, and D. B. Lowrie. 1996. Vaccination against tuberculosis by DNA injection. Nat. Med. 2:888-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trinchieri, G., M. Wysocka, A. D'Andrea, M. Rengaraju, M. Aste-Amezaga, M. Kubin, N. M. Valiante, and J. Chehimi. 1992. Natural killer cell stimulatory factor (NKSF) or interleukin-12 is a key regulator of immune response and inflammation. Prog. Growth Factor Res. 4:355-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsuji, T., K. Hamajima, J. Fukushima, K. Q. Xin, N. Ishii, I. Aoki, Y. Ishigatsubo, K. Tani, S. Kawamoto, Y. Nitta, J. Miyazaki, W. C. Koff, T. Okubo, and K. Okuda. 1997. Enhancement of cell-mediated immunity against HIV-1 induced by coinnoculation of plasmid-encoded HIV-1 antigen with plasmid expressing IL-12. J. Immunol. 158:4008-4013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolf, S. F., P. A. Temple, M. Kobayashi, D. Young, M. Dicig, L. Lowe, R. Dzialo, L. Fitz, C. Ferenz, and R. M. Hewick. 1991. Cloning of cDNA for natural killer cell stimulatory factor, a heterodimeric cytokine with multiple biologic effects on T and natural killer cells. J. Immunol. 146:3074-3081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu, X., N. Venkataprasad, H. S. Thangaraj, M. Hill, M. Singh, J. Ivanyi, and H. M. Vordermeier. 1997. Functions and specificity of T cells following nucleic acid vaccination of mice against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Immunol. 158:5921-5926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]