Abstract

Diarrheal disease caused by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli expressing the K88 (F4) fimbrial adhesin (K88 ETEC) is a significant source of mortality and morbidity among newborn and weaned piglets. K88 fimbrial adhesins are filamentous surface appendages whose lectin (carbohydrate-binding) activity allows K88 ETEC to attach to specific glycoconjugates (receptors) on porcine intestinal epithelial cells. There are three variants of K88 adhesin (K88ab, K88ac, and K88ad), which possess different, yet related, carbohydrate-binding specificities. We used porcine serum transferrin (pSTf) and purified glycosphingolipids (GSL) to begin to define the minimal recognition sequence for K88 adhesin variants. We found that K88ab adhesin binds with high affinity to pSTf (dissociation constant, 75 μM), while neither K88ac nor K88ad adhesin recognizes pSTf. Degradation of the N-glycan on pSTf by extensive metaperiodate treatment abolished its interaction with the K88ab adhesin, indicating that the K88ab adhesin binds to the single N-glycan found on pSTf. Using exoglycosidase digestion of the pSTf glycan, we demonstrated that K88ab adhesin recognizes N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) residues in the core of the N-glycan on pSTf. All three K88 variants were found to bind preferentially to GSL containing a β-linked N-acetylhexosamine (HexNAc), either GlcNAc or N-acetylgalactosamine, in the terminal position or, alternatively, in the penultimate position with galactose in the terminal position. Considering the results from pSTf and GSL binding studies together, we propose that the minimal recognition sequence for the K88 adhesin variants contains a β-linked HexNAc. In addition, the presence of a terminal galactose β-linked to this HexNAc residue enhances K88 adhesin binding.

Diarrheal disease caused by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli expressing the K88 (F4) fimbrial adhesin (K88 ETEC) is a significant source of mortality and morbidity among newborn and weaned piglets (9, 25, 38, 41, 59). K88 fimbrial adhesins are filamentous surface appendages whose lectin (carbohydrate-binding) activity allows K88 ETEC to attach to specific glycoconjugates (receptors) on porcine intestinal epithelial cells (28). Attachment of bacteria to their receptors on intestinal epithelial cells is an essential step in the colonization of the small intestine by ETEC.

Three serologically distinguishable variants of K88 adhesin (K88ab, K88ac, and K88ad) have been identified (21, 40). Each variant consists of a conserved antigenic region shared by all three variants, designated a, and variant-specific antigenic regions, designated b, c, and d for K88ab, K88ac, and K88ad, respectively (13, 29). The antigenic differences among the three K88 variants can be ascribed exclusively to a small number of nucleotide changes in the major fimbrial subunit gene, resulting in the amino acid substitutions that distinguish the three K88 variants. Several researchers have investigated the molecular interaction of K88 fimbrial adhesin variants with erythrocytes, intestinal mucus, and intestinal epithelial cells (4, 11, 12, 17, 19, 37, 39, 51, 58). It has been clearly demonstrated that all three K88 adhesin variants are lectins and that they recognize carbohydrate structures expressed on host cell glycoconjugates. Each K88 variant has a different, but related, carbohydrate-binding specificity. The differences in carbohydrate specificity among the three K88 adhesin variants are reflected in the different hemagglutination patterns of the K88 variants, determined by using erythrocytes from various species (6), and in the presence of multiple phenotypes of pigs whose intestinal epithelial cells contain receptors that bind different combinations of K88 adhesin variants (3, 5, 44).

Although it is clear that each K88 adhesin variant has a slightly different receptor binding specificity, the carbohydrate structures recognized by each variant have not been clearly delineated. Data from monosaccharide blocking studies indicate that N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) may be part of the receptor recognition site (2). Results from glycoprotein-blocking studies indicate that terminal GlcNAc, GalNAc, and galactose (Gal) may play a role in the interaction of the K88 adhesin with brush border receptors (2, 17). Also, Gal has been reported to be an important residue in the recognition of putative intestinal mucus receptors and glycosphingolipids (GSL) by the K88ab adhesin (8, 42). Recently, we determined that β-linked Gal is an essential component in the recognition of intestinal mucin-type sialoglycoproteins (IMTGP) by K88ac adhesin (18) and that the K88ad adhesin recognizes the terminal Galβ(1-4)GlcNAc on neolactotetraosylceramide (nLc4; Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glcβ1-1Cer) (20). Despite all of this work, no minimal core recognition sequence for the K88 adhesin variants has been identified. The objective of the present study was to more fully characterize the carbohydrate specificities of the K88 adhesin variants in order to define the core structure recognized by the K88 adhesin variants. Knowledge of the receptor specificities of the K88 fimbrial adhesins is essential for understanding the molecular mechanism of K88 ETEC adhesion and understanding the biochemical basis for genetic resistance of some piglets to K88 ETEC infections.

In the present paper, we used porcine serum transferrin (pSTf) and GSL standards as model receptors for the K88 fimbrial adhesin variants. pSTf was demonstrated to be a specific model receptor for the K88ab adhesin variant. Using exoglycosidase digestion studies, we demonstrated that the K88ab adhesin recognizes GlcNAc residues in the core of the N-glycan on pSTf. In addition, we compared the carbohydrate specificities of the three variants using a group of known GSL as model receptors. All three K88 variants were found to bind preferentially to GSL containing a β-linked N-acetylhexosamine (HexNAc), either GlcNAc or GalNAc, in the terminal position or, alternatively, in the penultimate position with Gal in the terminal position. Considering the results from pSTf and GSL binding studies together, we propose that the minimal recognition sequence for the K88 adhesin variants contains a β-linked HexNAc. In addition, the presence of a terminal Gal β-linked to this HexNAc residue enhances K88 adhesin binding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Organic solvents, GSL standards (lactocerebroside [Lc2], globotriaosylceramide [Gb3], globoside [Gb4], globopentaosylceramide [Gb5], asialogangliosides [GA2 and GA1], monosialogangliosides [GM3, GM2, and GM1], disialogangliosides [GD1a and GD1b]), and orcinol were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). Precoated high-performance thin-layer chromatography (HPTLC) plates (silica gel 60) with aluminum backing were obtained from E. Merck AG (Darmstadt, Federal Republic of Germany). Biotinylated plant lectins (concanavalin A [ConA] lectin, Griffonia simplicifolia lectin II, Ulex europaeus agglutinin [UEA], Ricinus communis agglutinin [RCA120], Maackia amurensis lectin I [MAL I], Erythrina cristagalli lectin [ECL], Solanum tuberosum lectin [STL], Lycopersicon esculentum lectin [LEL], and elderberry bark lectin [EBL]) were obtained from Vector Laboratories, Inc. (Burlingame, Calif.). Biotinylated K88 adhesins were prepared as described by Erickson et al. (11).

Purified GSL were prepared as follows. nLc4 and Lc3 were obtained sequentially by acid-catalyzed desialosylation and β-galactosidase treatment of bovine erythrocyte IV3NeuAc(Gc)nLc4 as described by Levery et al. (33). Lc4 was obtained by partial conversion of Lc3 with a recombinant human β-1,3-galactosyltransferase as described by Amado et al. (1). Lex was obtained from human adenocarcinoma (22, 23, 60). V3FucnLc6 was obtained from human granulocytes (16, 30, 54). VI2FucnLc6 was obtained from human O erythrocytes (32). Lea was isolated from a mixture of Folch lower-phase GSL extracted from pooled liver and colonic adenocarcinoma (22) and was kindly provided by Mark R. Stroud (Department of Cell Surface Biochemistry, Northwest Hospital, and Division of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Wash.).

pSTf purification.

pSTf was prepared by the procedure described previously by Grange and Mouricout (19). The resulting preparation was further purified by loading the sample onto a ConA-Sepharose column (1.2 by 30 cm) at room temperature (RT); the column was equilibrated with buffer A (0.5 M NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 M Tris [pH 7.0]) at a flow rate of 9 ml/h. Components of the sample not recognized by ConA were removed by washing the column with five column volumes of buffer A. Elution of the glycoproteins bound to the ConA column was accomplished by adding 30 ml of 0.3 M methyl-α-d-glucopyranoside dissolved in buffer A at RT. The eluted fractions containing pSTf were pooled, desalted by extensive dialysis against water, and lyophilized. During the purification procedure, pSTf was detected by immunoblotting assays with rabbit anti-human transferrin polyclonal antibodies (Dako Corporation) or mouse anti-pSTf monoclonal antibodies as described by Grange and Mouricout (19).

MLOA.

For the microplate lectin overlay assay (MLOA), pSTf was diluted into 50 mM carbonate-bicarbonate, pH 9.6, and then 0.1-ml samples were immobilized to 96-well Immulon I polystyrene plates (Dynatech, Alexandria, Va.) at 37°C for 16 h. The wells were rinsed three times with 0.2 ml of phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.5% Tween 20 (PBS-Tween). Biotinylated lectins (0.1 ml), diluted in PBS-Tween, were added to the wells and incubated at RT for 30 min. The wells were rinsed three times with 0.2 ml of PBS-Tween. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated to streptavidin (0.1 ml of a 0.43-μg/ml solution in PBS-Tween; Pierce) was added and incubated for 1 h at RT. The wells were rinsed three times with 0.2 ml of PBS-Tween, and the bound HRP-streptavidin was detected with chromogenic peroxidase substrate 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethyl-benzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) as previously described (14).

WBLOA.

Prior to electrophoresis, the protein concentrations of all samples tested were determined using the modified Lowry assay described by Peterson (43) with bovine serum albumin as the standard. For the Western blot lectin overlay assay (WBLOA), pSTf-containing samples were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (31) and then transferred to nitrocellulose or polyvinylidene difluoride filters (55). The filters were washed three times (15 min, RT) with 20 ml of PBS-Tween. Binding activity was detected by incubating the filter with 20 ml of PBS-Tween containing biotinylated lectin (0.5 μg/ml for K88 adhesin variants and 10 μg/ml for plant lectins) for 30 min at RT, followed by three washings (15 min, RT) with 20 ml of PBS-Tween. Bound biotinylated lectin was detected by incubating the filter with HRP-streptavidin (20 ml of a 0.43-μg/ml solution in PBS-Tween) for 1 h at RT. The filter was washed three times with 20 ml of PBS-Tween (10 min, RT), and the bound peroxidase activity was then detected with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine in the presence of CoCl2 as previously described (24).

HPTLC lectin overlay assay.

GSL were separated on HPTLC plates with chloroform-methanol-water (50:47:14 [vol/vol/vol]) containing 0.038% CaCl2 as described previously (45). Typically, two chromatograms were developed in parallel on the same HPTLC plate. One was sprayed with orcinol-sulfuric acid reagent to detect GSL (45), and the other was overlaid with biotinylated K88 adhesin variants (20). After separation, the dried chromatogram was sprayed with buffer B (0.01 M Na2HPO4, 0.14 M NaCl, 2% polyvinylpyrrolidone-40 [pH 7.2]). The plates were then immersed in buffer B for 1.5 h at RT with gentle stirring (20 rpm). The plates were removed from the buffer solution, and the excess buffer was allowed to drip off the plate. The plates were placed silica side down in buffered solutions containing biotinylated K88 adhesin variants (10 μg/ml) and incubated for 2 h at RT with gentle stirring (20 rpm). Unbound molecules were then removed by washing the plate two times for 10 min each in buffer B. Bound biotinylated K88 adhesins were detected by incubating the plate with HRP-streptavidin (1 μg/ml diluted in buffer B) for 1 h at RT with stirring. After two washes, the bound peroxidase activity was detected with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine in the presence of CoCl2 as previously described (24).

Metaperiodate treatment of pSTf.

Purified pSTf (2 μg) was separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose filters. Replicate filters (three at each time point) were then incubated in 10 mM sodium metaperiodate dissolved in 0.2 M sodium acetate, pH 4.1, for various periods of time at 37°C on a rotator. Control digests were performed under identical conditions with 10 mM sodium metaperiodate replaced with 10 mM sodium iodate. The filters were then washed three times with MilliQ water for 5 min at RT. Replicate filters were stained with Coomassie blue R-250 and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain (53) and were subjected to the WBLOA procedure described above.

Exoglycosidase treatments.

Purified pSTf (1.8 mg) was digested with Vibrio cholerae neuraminidase (80 mU; Boehringer Mannheim Corp., Indianapolis, Ind.) in neuraminidase digestion buffer (50 mM sodium acetate, 154 mM NaCl, 9 mM CaCl2, pH 5.5) for 24 h at 37°C. The neuraminidase-digested pSTf was dialyzed extensively against β-galactosidase digestion buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 100 mM NaCl, pH 6.5), and then a portion (1.2 mg) of this digested pSTf was treated with Diplococcus pneumoniae β-galactosidase (30 mU; Boehringer Mannheim Corp.) for 24 h at 37°C. The neuraminidase- and β-galactosidase-digested pSTf was dialyzed extensively against β-N-acetylhexosaminidase (HexNAcase) digestion buffer (75 mM citrate-phosphate, pH 4.8), and then a portion (0.4 mg) of this digested pSTf was treated with jack bean meal HexNAcase (0.5 U; Oxford Glycosciences, Wakefield, Md.) for 24 h at 37°C. Control digestions without pSTf were performed under the identical conditions (same buffers, reactants, digestion times, and dialysis times) as those for the exoglycosidase digestions of pSTf. All treated samples of pSTf, along with control samples, were then tested for their ability to bind biotinylated lectins by the MLOA described above. The absorbance of the appropriate control digest was subtracted from the absorbance of the exoglycosidase-treated pSTf to determine the final intensity of lectin binding.

RESULTS

Binding of K88 fimbrial adhesin variants to pSTf.

To determine if pSTf is a suitable model receptor for the K88 fimbrial adhesin variants, we first purified pSTf using the procedure described by Grange and Mouricout (19). The purity of the pSTf preparation was assessed by SDS-PAGE analysis of 2 μg of purified pSTf/lane followed by detection with Coomassie blue, antitransferrin antibodies, and PAS stain. Coomassie blue staining detected a 76-kDa band that represented over 98% of the total protein detected in that lane (Fig. 1BII, lane 1). A polyclonal antibody to human serum transferrin and a monoclonal antibody to pSTf bound to this 76-kDa glycoprotein, indicating that this protein is pSTf (data not shown). PAS staining also detected the 76-kDa band, demonstrating that pSTf is the only detectable glycoprotein in the preparation (Fig. 1CII, lane 1).

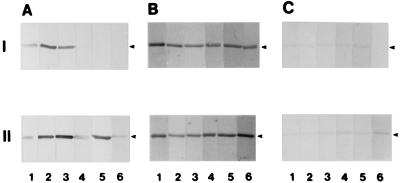

FIG. 1.

Periodate inactivation of the binding of the K88ab fimbrial adhesin to pSTf. Purified pSTf was subjected to treatment with sodium metaperiodate (I) and sodium iodate (II) for 15 min (lane 1), 30 min (lane 2), 1 h (lane 3), 2 h (lane 4), 24 h (lane 5), and 48 h (lane 6) as described in Materials and Methods. The treated samples (2 μg of pSTf per lane) were run on SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide) gels and then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes as described in Materials and Methods. K88ab binding activity was detected with biotinylated K88ab adhesin (A), proteins were detected by Coomassie blue staining (B), and glycoproteins were detected by PAS staining (C). Arrowheads indicate the migration position of pSTF.

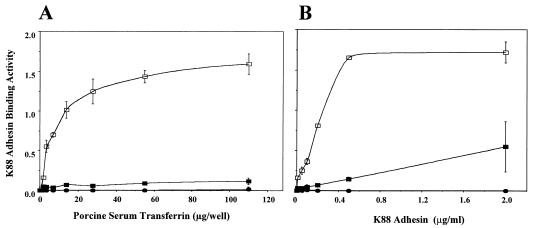

To determine if the K88 adhesin variants bind to pSTf, we immobilized various amounts of purified pSTf to 96-well polystyrene plates, overlaid the pSTf with the three biotinylated K88 adhesin variants, and detected the amount of bound biotinylated K88 adhesin using an HRP-streptavidin detection system. We found that K88ab, but not K88ac or K88ad, adhesin bound strongly to pSTf (Fig. 2A). To assess the affinity of K88 adhesin variants for pSTf, we immobilized pSTf to 96-well polystyrene plates, overlaid it with various concentrations of the three biotinylated K88 adhesin variants, and detected the amount of bound biotinylated K88 adhesin (Fig. 2B). Only the K88ab adhesin variant showed strong binding to pSTf (Fig. 2B). A double-reciprocal plot of this binding data was used to determine that the dissociation constant for the binding of K88ab adhesin to pSTf is 75 μM.

FIG. 2.

Binding of K88 adhesin variants to purified pSTF. (A) Purified pSTf (0.43 to 110 μg/ml) was immobilized to 96-well polystyrene plates and probed with biotinylated K88ab (□), K88ac (▪), and K88ad (•) adhesin variants (2 μg/ml) for 1 h at RT. (B) Purified pSTf (60 μg per well) was immobilized overnight at 37°C onto a 96-well plate and probed with various concentrations of biotinylated K88 adhesin variants ranging from 0.01 to 2 μg/ml for 1 h at RT. Bound biotinylated K88 adhesins were detected with HRP-streptavidin as described in Materials and Methods.

Implication of the glycanic moiety of pSTf in recognition by the K88ab adhesin.

The binding of K88ab ETEC to intestinal epithelial cells is mediated by the recognition of a specific carbohydrate on the surface of intestinal epithelial cells by the K88ab adhesin (47). Consequently, for pSTf to be a useful model receptor, the K88ab adhesin must interact with the carbohydrate moiety of pSTf. To demonstrate that the recognition of pSTf by the K88ab adhesin was through the carbohydrate moiety, we treated purified pSTf with sodium metaperiodate to degrade the glycan on pSTf and then tested to see if the treated pSTf could bind K88ab adhesin (Fig. 1I). As a negative control, we treated pSTf with sodium iodate, which does not degrade glycans (Fig. 1II). After 2 h of treatment, the metaperiodate-treated pSTf was no longer recognized by the K88ab adhesin (Fig. 1AI, lane 4). In contrast, iodate-treated pSTf was still recognized by the K88ab adhesin even after 48 h of treatment (Fig. 1AII, lane 6). These results indicate that the K88ab adhesin interacts with the glycanic moiety of pSTf. In addition to testing for the K88ab adhesin-binding ability of the treated pSTf, we performed Coomassie blue (Fig. 1B) and PAS (Fig. 1C) staining of each treated sample. These results verified that periodate did not degrade the protein moiety of pSTf but slowly degraded the carbohydrate moiety, with complete destruction of the carbohydrate, as evidenced by the lack of PAS staining after 48 h of incubation with sodium metaperiodate (Fig. 1CI, lane 6).

Characterization of the glycanic moiety of pSTf.

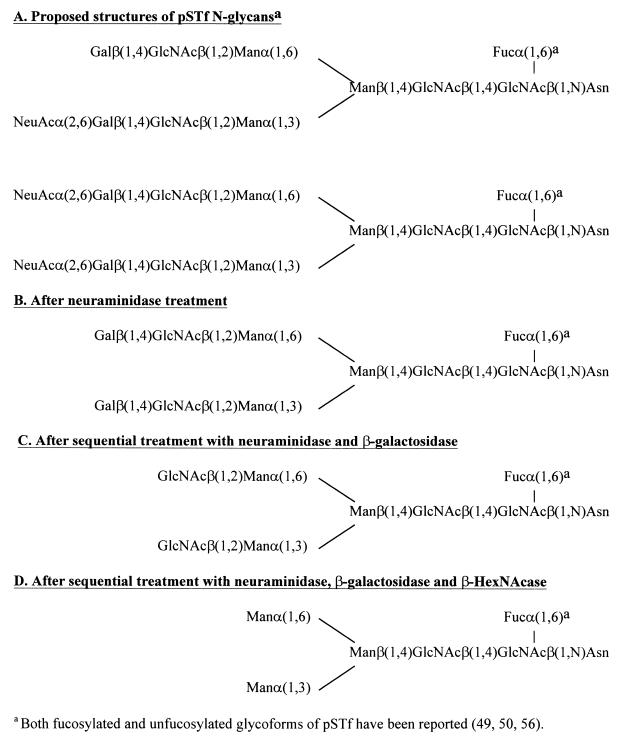

Results from previous studies have shown that preparations of pSTf contain a combination of glycoforms that each possess a single biantennary complex N-glycan having the structures shown in Fig. 3 (49, 50, 56). To characterize the glycan present on the pSTf that we isolated for this study, we used biotinylated lectin binding studies and exoglycosidase digestion studies (Table 1). ConA lectin bound to pSTf, verifying the presence of an N-glycan (Table 1). Purified pSTf also bound RCA120 and EBL, indicating the presence of Gal and α(2-6)-linked NeuAc, respectively, in terminal positions (Table 1). Also, ECL which is specific for Galβ(1-4)GlcNAc, bound to pSTf, while closely related lectin MAL I, which is specific for Galβ(1-3)GlcNAc, did not react (Table 1). In addition, UEA, which is specific for α-linked fucose, weakly bound to pSTf, indicating that our pSTf preparation contains at least some fucosylated pSTf glycoforms.

FIG. 3.

Proposed structures of the N -glycan on pSTf before and after exoglycosidase digestions.

TABLE 1.

Reactivities of biotinylated lectins with untreated and exoglyocosidase-treated pSTf

| Lectin | Carbohydrate specificity | Intensity of biotinylated lectin bindinga to:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated pSTf | Neuraminidase- treated pSTf | Neuraminidase + β-galactosidase-treated pSTf | Neuraminidase + β-galactosidase + β-HexNAcase-treated pSTf | ||

| K88ab adhesin | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | |

| EBL | Terminal α(2,6)-linked NeuAc | +++ | − | − | − |

| RCA120 | Terminal β-Gal | + | +++ | − | − |

| G. simplicifolia II | Terminal GlcNAc | − | − | + | − |

| ConA | N-linked glycans with α-linked Man | + | + | ++ | +++ |

| STL | GlcNAc oligomers | − | − | + | +++ |

| LEL | GlcNAc oligomers | − | + | + | +++ |

| ECL | Galβ(1,4)-GlcNAc | +b | NDc | ND | ND |

| MAL 1 | Galβ(1,3)-GlcNAc | −b | ND | ND | ND |

| UEA 1 | α-Fuc | +b | ND | ND | ND |

The intensity of biotinylated lectin binding was determined by using the MLOA as described in Materials and Methods, except where indicated otherwise (see footnote b), and is indicated as follows: mean absorbance of triplicate samples minus the control was >0.10 when amounts of treated pSTf immobilized to the well were ≥0.28 (+++), 2.25 (++), and 9 μg (+). −, absorbance was less than 0.10 at all amounts of treated pSTf tested.

Binding intensity was determined by WBLOA as described in Materials and Methods. +, binding; and −, no binding.

ND, not determined.

To further evaluate the structure of the glycan on pSTf and to determine the monosaccharides on pSTf recognized by the K88ab adhesin, we treated pSTf with specific exoglycosidases to sequentially remove terminal monosaccharides and then verified the removal of the appropriate monosaccharides with biotinylated plant lectins. The effect of exoglycosidase treatment on the K88ab adhesin-binding activity of the receptors was also evaluated by K88ab adhesin overlay assays. Treatment of pSTf with neuraminidase increased K88ab adhesin-binding activity, inhibited EBL binding, and enhanced RCA120 binding to pSTf (Table 1). These results indicate that terminal NeuAc residues were removed to expose Gal residues, and removal enhanced recognition of pSTf by the K88ab adhesin (Fig. 3B). Since the reactivity of pSTf with RCA120 was initially low and was then greatly enhanced when the NeuAc residues were removed, it is likely that at least some of pSTf in our preparation is the disialylated glycoforms (Fig. 3A). Sequential treatment of pSTf with neuraminidase followed by β-galactosidase increased the K88ab adhesin-binding activity in comparison to that of the untreated control, completely abolished recognition of pSTf by RCA120 lectin, and enhanced recognition by G. simplicifolia II lectin (Table 1). These results indicate that the Gal residues that are exposed by treatment of the pSTf with neuraminidase are not required in the recognition of pSTf by the K88ab adhesin (Fig. 3C). Sequential treatment of pSTf with neuraminidase followed by β-galactosidase and then HexNAcase increased the K88ab adhesin-binding activity of pSTf in comparison to that of the untreated control, completely abolished recognition of pSTf by G. simplicifolia II lectin, and enhanced binding by ConA (Table 1). These results indicate that the pSTf contains NeuAc, β-linked Gal, and β-linked GlcNAc, which is consistent with the structures shown in Fig. 3A. These results indicate that the terminal three carbohydrate residues [NeuAcα(2,6)Galβ(1,4)GlcNAcβ] are not an essential part of the recognition site for K88ab adhesin on pSTf. In fact, removing these residues enhances binding of K88ab adhesin to pSTF. Two possible explanations for this increased binding are that (i) the K88ab adhesin recognizes the newly exposed Man (Fig. 3D) and (ii) removal of the terminal three residues on each antenna causes a conformational change in the remaining oligosaccharide, which makes it a better receptor for K88ab adhesin. The second explanation seems more likely since K88ab adhesin binding has been demonstrated to be mannose resistant (48). Additional evidence for a conformational change in the oligosaccharide comes from experiments where we found that removal of the terminal three carbohydrate residues [NeuAcα(2,6)Galβ(1,4)GlcNAc-] from pSTf enhances binding of two lectins, STL and LEL, that are known to react with GlcNAc oligomers (Table 1). From these studies, it seems likely that K88ab adhesin binds to one or both of the GlcNAc residues that make up the core of the pSTf N-glycan and that the K88ab adhesin binds more intensely to high-mannose N-glycans (Fig. 3D) than to complex N-glycans (Fig. 3A).

Determination of K88ab binding specificity with GSL.

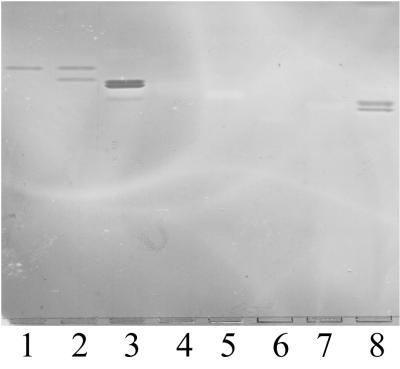

To further characterize the glycanic structures recognized by the K88 adhesin variants, we tested 19 purified GSL standards, which can be divided into four groups (lactosyl, neolactosyl, globosyl, and gangliosyl) for their ability to bind the three K88 adhesin variants (Fig. 4; Table 2). Within the lactosyl group, all three K88 variants bound to Lc3, K88ac bound to Lc4, and K88ad bound to Lc2. Within the neolactosyl group, all three K88 variants bound to nLc4 and nLc6. Within the globosyl family, all three variants bound to Gb3. Within the gangliosyl group, all three variants recognized GA2 and GA1 and K88ac bound to GM3. Overall, the three K88 variants bind to many of the same GSL, indicating that they have similar receptor binding specificities. However, there are also some differences in their receptor specificities, as evidenced by the variation in their recognition of some of the GSL.

FIG. 4.

Binding of K88ac adhesin to GSL standards. Two micrograms of Lc3 (lane 1), Lc3 plus Lc4 (lane 2), nLc4 (lane 3), Lea (lane 4), Lex (lane 5), V3FucnLc6 (lane 6), VI2FucnLc6 (lane 7), and nLc6 (lane 8) was separated on HPTLC plates. These GSL were incubated with biotinylated K88ac adhesin as described in Materials and Methods.

TABLE 2.

Binding of K88 adhesin variants to GSL standards

| GSL | Structure | Intensity of bindinga to:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K88ab | K88ac | K88ad | ||

| Lactosyl | ||||

| Lc2 | Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer | − | − | + |

| Lc3 | GlcNAcβ(1-3)Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer | + | + | + |

| Lc4 | Galβ(1-3)GlcNAcβ(1-3)Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer | − | + | + |

| Lea | Galβ(1-3)[Fucα(1-4)]GlcNAcβ(1-3)Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer | − | − | − |

| Neolactosyl | ||||

| nLc4 | Galβ(1-4)GlcNAcβ(1-3)Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Lex | Galβ(1-4)[Fucα(1-3)]GlcNAcβ(1-3)Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer | − | − | − |

| nLc6 | Galβ(1-4)GlcNAcβ(1-3)Galβ(1-4)GlcNAcβ(1-3)Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer | + | ++ | +++ |

| V3FucnLc6 | Galβ(1-4)[Fucα(1-3)]GlcNAcβ(1-3)Galβ(1-4)GlcNAcβ(1-3)Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer | − | − | − |

| VI2FucnLc6 | Fucα(1-2)Galβ(1-4)GlcNAcβ(1-3)Galβ(1-4)GlcNAcβ(1-3)Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer | − | − | − |

| Globosyl | ||||

| Gb3 | Galα(1-4)Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer | + | + | +++ |

| Gb4 | GalNAcβ(1-3)Galα(1-4)Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer | − | − | − |

| Gb5 | GalNAcβ(1-3)GalNAcβ(1-3)Galα(1-4)Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer | − | − | − |

| Gangliosyl | ||||

| GA2 | GalNAcβ(1-4)Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| GA1 | Galβ(1-3)GalNAcβ(1-4)Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| GM3 | NeuAcα(2-3)Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer | − | + | − |

| GM2 | GalNAcβ(1-4)[NeuAcα(2-3)]Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer | − | − | − |

| GM1 | Galβ(1-3)GalNAcβ(1-4)[NeuAcα(2-3)]Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer | − | − | − |

| GD1a | NeuAcα(2-3)Galβ(1-3)GalNAcβ(1-4)[NeuAcα(2-3)]Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer | − | − | − |

| GD1b | Galβ(1-3)GalNAcβ(1-4)[NeuAcα(2-8) NeuAcα(2-3)]Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer | − | − | − |

The intensity of K88 adhesin binding was determined by using the HPTLC overlay assay described in Materials and Methods.+++, high-intensity binding; ++, medium-intensity binding; +, low-intensity binding; −, no detectable binding. See Fig. 4 for representative examples of binding intensities.

DISCUSSION

With respect to receptor recognition, the P pilus adhesin found on uropathogenic strains of E. coli is one of the best-characterized fimbrial adhesins (26). As with the K88 adhesin, three different variants of P pili (class I, class II, and class III) have been identified (10, 35, 36). All three classes of P pili recognize globoseries GSL that contain the Galα(1-4)Gal (galabiose) core structure found on human P blood group antigens. However, the different variants of P pili do not bind equally well to all galabiose-containing receptors. Class I P pili preferentially bind to Gb3 [Galα(1-4)Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer] (35), while class II pili bind to Gb4 [GalNAcβ(1-3)Galα(1-4)Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer] (52) and class III pili prefer Forssmanantigen [Gb5; GalNAcβ(1-3)GalNAcβ(1-3)Galα(1-4)Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer] (36). It seems logical that variants of a particular adhesin would have related carbohydrate specificities, since it is not likely that a whole new carbohydrate-binding pocket would be created in each variant. It is much more likely that variants of an adhesin have similar carbohydrate-binding pockets, which have been modified to produce slightly different binding specificities. The K88 adhesin variants may be similar to the P pilus variants in having different, yet related, carbohydrate-binding specificities. Therefore, we hypothesized that the three K88 variants recognize a core mono-, di-, or trisaccharide structure and that each variant prefers different substitutions or modifications to that core structure. The objective of the present study was to define the core structure recognized by the three K88 adhesin variants by comparing the binding specificities of the three K88 variants by using pSTf and GSL as model receptors.

The cores of all N-glycans contain Manβ(1,4)GlcNAcβ(1,4)GlcNAcβ(1,N)Asn (57). Consequently, the K88ab adhesin, which was shown in the present study to bind to GlcNAc residues in the core of the N-glycans, could potentially bind to all N-glycosylated proteins. This observation is consistent with previous reports that the K88ab adhesin binds to more glycoproteins in crude intestinal extracts than either of the other two K88 variants (7). Despite the fact that all N-glycans possess the same core structure, it is not likely that K88ab adhesin binds equally well to all N-glycans, as the GlcNAc residues may be more accessible or in a more favorable conformation in certain types of N-glycans. For example in the present study, lectin binding to the N-glycan on pSTf was higher when the antennae of the N-glycans were shortened by exoglycosidase treatment. This observation is supported by the fact that STL and LEL, along with the K88ab adhesin, react much more intensely with exoglycosidase-digested pSTf than with undigested pSTf. Consequently, GlcNAc-specific lectins, such as LEL, STL, and K88ab adhesin, bind more intensely to high-mannose N-glycans than to complex N-glycans. Modifications to the core structure may also affect K88ab adhesin binding to N-glycans. One of the most common direct modifications to the core structure of N-glycans is the addition of Fuc α(1,6)-linked to the GlcNAc residue attached to the asparagine. This modification may inhibit the binding of K88ab adhesin to N-glycans in a manner similar to what we observed with GSL, where fucosylation of the GlcNAc in nLc4 to produce Lex destroys its K88 adhesin-binding ability (Table 2). Further evidence that fucosylation may affect K88ab binding comes from a study by L'Hote et al. (34), where they observed that the K88ab adhesin does not interact with the Aα subunit of porcine fibrinogen, which contains the same fucosylated N-glycan found on some glycoforms of pSTf (Fig. 3A).

Previously, Grange and Mouricout (19) reported that the K88ab adhesin bound to porcine intestinal transferrin (pITf) on enterocytes from susceptible, but not resistant, pigs. In this same study, they also reported the binding of K88ab adhesin to the more abundantly available form of transferrin found in the serum (pSTf) and found that pSTf from all pigs tested bound K88ab adhesin. Thus, there is no correlation between K88ab binding to pSTf and the animal's susceptibility to K88ab ETEC-induced disease. It has been demonstrated that pSTf contains a single glycan that is N linked to Asn-497, located near the C terminus of the molecule (49). This glycan has been shown to be a biantennary complex N-glycan with the structures shown in Fig. 3 (49, 50, 56). The pSTf that we isolated in the present study is most likely a mixture of glycoforms containing fucosylated and unfucosylated glycans that are either mono- or disialyated (Table 1; Fig. 3A). The structure of the N-glycan on pITf has not been clearly elucidated. However, Grange and Mouricout (19) reported that the carbohydrate compositions of the two forms pITf and pSTf are similar. It would be quite informative to compare the structures of the N-glycans on pITf from susceptible versus resistant pigs. One possibility is that the pSTf from the resistant pigs may consist predominantly of fucosylated glycoforms that do not bind K88ab adhesin.

The core structure that is most consistently found in the GSL that all three variants bind to is HexNAc β-linked [either GalNAcβ(1-4) or GlcNAc β(1-3)] to Gal. Addition of a Gal, either β(1-4)-linked to a GlcNAc or β(1-3)-linked to a GalNAc, does not disrupt the binding of the K88 variants to the core structure. In fact, addition of Gal β(1-4)-linked to GlcNAc, as seen when comparing binding to Lc3 and binding to nLc4, actually enhances the intensity of binding of all three variants. In contrast, modification of the HexNAc with Fuc destroys its K88 adhesin-binding ability, as demonstrated by the lack of binding to Lex, which is fucosylated nLc4. In addition, modification of the Gal found in the core structure with NeuAc, as seen when GA2 and GA1 are converted to GM2 and GM1, respectively, abolishes the binding of all three K88 variants. It appears that the core recognition sequence for K88 adhesins, HexNAc β-linked to Gal, must be positioned close to the nonreducing terminus. This is evidenced by the presence of a potential internal unsubstituted core recognition sequence for K88 adhesin in both VI2FucnLc6 and V3FucnLc6 that does not bind any of the K88 adhesin variants. The binding of all three variants to Gb3 is hard to reconcile with the remainder of the GSL results, since Gb3 does not contain the proposed core recognition sequence. One possibility is that the K88 variants recognize, weakly for K88ab and K88ac, the terminal Gal in Gb3. It is difficult with the limited number of GSL tested to define the structural basis of the differences in the specificities of the three variants, but further studies using both model and natural receptors will allow these comparisons to be made.

Many different types of studies, including studies of monosaccharide and glycoprotein blocking of hemagglutination and brush border binding, have been performed to determine the binding specificities of the three variants of K88 adhesin (2, 8, 17, 42). All of these studies conclude that Gal, GlcNAc, GalNAc, or some combination of these monosaccharides has a role in K88 adhesin recognition. Recently, we determined that the K88ac adhesin interacts with β-linked Gal on IMTGP (18) and that the K88ad adhesin recognizes the terminal Galβ(1-4)GlcNAc on the neutral GSL, nLc4 [Galβ(1-4)GlcNAcβ(1-3)Galβ(1-4)Glcβ(1-1)Cer] (20). In addition, Seignole et al. (46) proposed that the K88ac adhesin recognizes Galβ(1-3)GalNAc and Fucα(1-2)Galβ(1-3/4)GalNAc on IMTGP. We have been unable to verify that Fuc is involved in K88 adhesin recognition of either IMTGP (P. A. Grange and A. K. Erickson, unpublished observation) or GSL (Table 2). The results in the present study are consistent with most of the earlier findings and extend these finding by directly comparing the binding specificities of the three K88 adhesin variants by using common model receptors. Based on the present findings, we propose that the minimal carbohydrate structure needed for recognition by K88 adhesin variants contains a HexNAc β-linked to a Gal residue and that a terminal Gal β-linked to the HexNAc enhances K88 adhesin binding but is not essential for recognition of glycans by K88 adhesins.

One of our long-term goals is to determine the differences in carbohydrate specificity among the K88 adhesin variants. The results obtained in the present study shed some light on the similarities in binding specificities among the K88 variants but do not reveal much about the molecular basis of the differences in carbohydrate specificity among the K88 variants. To address this problem, studies comparing the structures of the glycans recognized by the K88 adhesin variants on the phenotype-specific receptors (7) from intestinal epithelial cells (intestinal glycolipid K88ad receptor for K88ad [20], IMTGPs for K88ab and K88ac [7, 11, 12, 15, 27, 46], and pITf for K88ab [19]) need to be performed. Determination of these structures will make it possible to begin to understand the changes in receptor specificity that occur during evolutionary development of new adhesin variants and to synthesize structural analogues of the receptor recognition sequence which can be used to prevent and treat K88 ETEC-induced disease in pigs.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge USDA NRI-CGP grants 97-03708 and 2000-02200 for providing financial assistance.

Editor: V. J. DiRita

REFERENCES

- 1.Amado, M., R. Almeida, F. Carneiro, S. B. Levery, E. H. Holmes, M. Nomoto, M. A. Hollingsworth, H. Hassan, T. Schwientek, P. Neilsen, E. Bennett, and H. Clausen. 1998. A family of human β3-galactosyltransferases. Characterization of four members of a UDP-galactose:β-N-acetyl-glucosamine/β-N-acetyl galactosamine β-1,3-galactosyltransferase family. J. Biol. Chem. 273:12770-12778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, M. J., J. S. Whitehead, and Y. S. Kim. 1980. Interaction of Escherichia coli K88 antigen with porcine intestinal brush border membranes. Infect. Immun. 29:897-901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker, D., L. O. Billey, and D. H. Francis. 1997. Distribution of K88 Escherichia coli-adhesive and nonadhesive phenotypes among pigs of four breeds. Vet. Microbiol. 54:123-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakker, D., P. T. J. Willemsen, L. H. Simons, F. G. van Zjderveld, and F. K. de Graaf. 1992. Characterization of the antigenic and adhesive properties of FaeG, the major subunit of K88 fimbriae. Mol. Microbiol. 6:247-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bijlsma, I. G. W., A. de Nijs, C. van der Meer, and J. F. Frik. 1982. Different pig phenotypes affect adherence of Escherichia coli to jejunal brush borders by K88ab, K88ac, or K88ad antigen. Infect. Immun. 37:891-894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bijlsma, S. G. M., and J. F. Frik. 1987. Hemagglutination patterns of the different variants of Escherichia coli K88 antigen with porcine, bovine, guinea pig, chicken, ovine, and equine erythrocytes. Res. Vet. Sci. 43:122-123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Billey, L. O., A. K. Erickson, and D. H. Francis. 1997. Multiple receptors on porcine intestinal epithelial cells for the three variants of Escherichia coli K88 fimbrial adhesin. Vet. Microbiol. 59:203-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blomberg, L., H. C. Krivan, P. S. Cohen, and P. L. Conway. 1993. Piglet ileal mucus contains protein and glycolipid (galactosylceramide) receptors specific for Escherichia coli K88 fimbriae. Infect. Immun. 61:2526-2531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi, C., and C. Chae. 1999. Genotypic prevalence of F4 variants (ab, ac, and ad) in Escherichia coli isolated from diarrheic piglets from Korea. Vet. Microbiol. 67:307-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clegg, S. 1982. Cloning the genes determining the production of mannose-resistant fimbriae in the uropathogenic strain of Escherichia coli belonging to serogroup O6. Infect. Immun. 38:739-744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erickson, A. K., J. A. Willgohs, S. Y. McFarland, D. A. Benfield, and D. H. Francis. 1992. Identification of two porcine brush border glycoproteins that bind the K88ac adhesin of Escherichia coli and correlation of these glycoproteins with the adhesive phenotype. Infect. Immun. 60:983-988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erickson, A. K., D. R. Baker, B. T. Bosworth, T. A. Casey, D. A. Benfield, and D. H. Francis. 1994. Characterization of porcine intestinal receptors for the K88ac fimbrial adhesin of Escherichia coli as mucin-type sialoglycoproteins. Infect. Immun. 62:5404-5410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foged, N. T., P. Klemm, F. Elling, S. E. Jorsal, and J. Zeuthen. 1986. Monoclonal antibodies to K88ab, K88ac, and K88ad fimbriae from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Microb. Pathog. 1:57-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Francis, D. H., C. J. Ryan, and J. D. Fritzemeier. 1983. Effect of sodium acetate on expression of K99 pili by Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 41:1368-1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francis, D. H., P. A. Grange, D. H. Zeman, D. R. Baker, R. Sun, and A. K. Erickson. 1998. Expression of mucin-type glycoprotein K88 receptors strongly correlates with piglet susceptibility to K88+ enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, but adhesion of this bacterium to brush borders does not. Infect. Immun. 66:4050-4055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukuda, M. N., A. Dell, J. E. Oates, P. Wu, J. C. Klock, and M. Fukuda. 1985. Structures of glycosphingolipids isolated from human granulocytes. The presence of a series of linear poly-N-acetyllactosaminylceramide and its significance in glycolipids of whole blood cells. J. Biol. Chem. 260:1067-1082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibbons, R. A., G. W. Jones, and R. Sellwood. 1975. An attempt to identify the intestinal receptor for the K88 adhesin by means of a hemagglutination inhibition test using glycoproteins and fractions from sow colostrum. J. Gen. Microbiol. 86:228-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grange, P. A., A. K. Erickson, T. J. Anderson, and D. H. Francis. 1998. Characterization of the carbohydrate moiety of intestinal mucin-type sialoglycoprotein receptors for the K88ac fimbrial adhesin of Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 66:1613-1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grange, P. A., and M. A. Mouricout. 1996. Transferrin associated with the porcine intestinal mucosa is a receptor specific for K88ab fimbriae of Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 64:606-610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grange, P. A., A. K. Erickson, S. B. Levery, and D. H. Francis. 1999. Identification of an intestinal neutral glycosphingolipid as a phenotype-specific receptor for the K88ad adhesin of Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 67:165-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guinee, P. A. M., and W. H. Jansen. 1979. Behavior of Escherichia coli K antigens K88ab, K88ac, and K88ad in immunoelectrophoresis, double diffusion, and hemagglutination. Infect. Immun. 23:700-705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hakomori, S., E. Nudelman, R. Kannagi, and S. B. Levery. 1982. The common structure in fucosyllactosaminolipids accumulating in human adenocarcinomas, and its possible absence in normal tissue. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 109:36-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hakomori, S., E. Nudelman, S. B. Levery, D. Solter, and B. B. Knowles. 1981. The hapten structure of a developmentally regulated glycolipid antigen (SSEA-1) isolated from human erythrocytes and adenocarcinoma: a preliminary note. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 100:1578-1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harlow, E., and D. Lane. 1988. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 25.Henton, M. M., and M. M. Engelbrecht. 1997. Escherichia coli serotypes in pigs in South Africa. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 64:175-187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hultgren, S. J., S. Abraham, M. Caparon, P. Falk, J. W. I. St. Geme, and S. Normark. 1993. Pilus and non-pilus bacterial adhesins: assembly and function in cell recognition. Cell 73:887-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeyasingham, M. D., P. Butty, T. P. King, R. Begbie, and D. Kelly. 1999. Escherichia coli K88 receptor expression in intestine of disease-susceptible weaned pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 68:219-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones, G. W., and J. M. Rutter. 1972. Role of the K88 antigen in the pathogenesis of neonatal diarrhea caused by Escherichia coli in piglets. Infect. Immun. 6:918-927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Josephsen, J., F. Hansen, F. K. de Graaf, and W. Gaastra. 1984. The nucleotide sequence of the K88ac fimbriae of porcine enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 25:301-306. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kannagi, R., E. Nudelman, S. B. Levery, and S. Hakomori. 1982. A series of human erythrocyte glycosphingolipids reacting to the monoclonal antibody directed to a developmentally regulated antigen, SSEA-1. J. Biol. Chem. 257:14865-14874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levery, S. B., E. D. Nudelman, N. H. Andersen, and S. Hakomori. 1986. 1H-NMR analysis of glycolipids possessing mono- and multimeric X and Y haptens: characterization of two novel extended Y structures from human adenocarcinoma. Carbohydr. Res. 151:311-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levery, S. B., E. H. Holmes, D. D. Harris, and S. Hakomori. 1992. 1H-NMR studies of a biosynthetic lacto-ganglio hybrid glycosphingolipid: confirmation of structure, interpretation of “anomalous” chemical shifts, and evidence for interresidue amide-amide hydrogen bonding. Biochemistry 31:1069-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.L'Hote, C., S. Berger, S. Bourgerie, Y. Duval-Iflah, R. Julien, and Y. Karamanos. 1995. Use of porcine fibrinogen as a model glycoprotein to study the binding specificity of the three variants of K88 lectin. Infect. Immun. 63:1927-1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindberg, F. P., B. Lund, and S. Normark. 1984. Genes of the pyelonephritogenic E. coli required for digalactoside-specific agglutination of human cells. EMBO J. 3:1167-1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lund, B., B. I. Marklund, N. Stromberg, F. Lindberg, K. A. Karlsson, and S. Normark. 1988. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli can express serologically identical pili of different receptor binding specificities. Mol. Microbiol. 2:255-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Metcalfe, J. W., K. A. Krogfelt, H. C. Krivan, S. C. Cohen, and D. C. Laux. 1991. Characterization and identification of a small intestine mucus receptor for the K88ab fimbrial adhesin. Infect. Immun. 59:91-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moon, H. W., and T. O. Bunn. 1993. Vaccines for preventing enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infections in farm animals. Vaccine 11:213-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nilsson, G., and S. Svensson. 1983. The role of the carbohydrate portion of glycolipids for the adherence of Escherichia coli K88+ to pig intestine, p. 637-638. In M. A. Chester, D. Heinegard, A. Lundblad, and S. Svensson (ed.), Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Glycoconjugates. Lund-Ronneby, Sweden.

- 40.Orskov, I., F. Orskov, W. J. Sojka, and W. Wittig. 1964. K antigens K88ab(L) and K88ac(L) in E. coli. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 62:439-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osek, J. 1999. Prevalence of virulence factors of Escherichia coli strains isolated from diarrheic and healthy piglets after weaning. Vet. Microbiol. 68:209-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Payne, D., M. O'Reilly, and D. Williamson. 1993. The K88 fimbrial adhesin of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli binds to β1-linked galactosyl residues in glycosphingolipids. Infect. Immun. 61:3673-3677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peterson, G. L. 1983. Determination of total protein. Methods Enzymol. 91:95-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rapacz, J., and H. Hasler-Rapacz. 1986. Polymorphism and inheritance of swine small intestinal receptors mediating adhesion of three serological variants of Escherichia coli producing K88 pilus antigen. Anim. Genet. 17:305-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schnaar, R. L., and L. Needham. 1994. Thin-layer chromatography of glycosphingolipids. Methods Enzymol. 230:371-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seignole, D., P. Grange, Y. Duval-Iflah, and M. Mouricout. 1994. Characterization of O-glycan moieties of the 210 and 240 kDa pig intestinal receptors for Escherichia coli K88ac fimbriae. Microbiology 140:2467-2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sellwood, R. 1980. The interaction of the K88 antigen with porcine intestinal epithelial cell brush borders. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 632:326-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sellwood, R. 1981. The K88 adherence system in swine, p. 22-28. In E. C. Boedeker (ed.), Attachment of organisms to the gut mucosa. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 49.Sharma, N., R. Evans, K. Patel, B. Gorinsky, A. Mallet, and A. Aitken. 1994. Evidence for the glycosylation of porcine serum transferrin at a single site located with the C-terminal lobe. Biochem. Biophys. Acta 1206:286-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spik, G., B. Coddeville, and J. Montreuil. 1988. Comparative study of the primary structures of sero-, lacto- and ovotransferrin glycans from different species. Biochimie (Paris) 70:1459-1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Staley, T. E., and I. B. Wilson. 1983. Soluble pig intestinal cell membrane components with affinities for E. coli K88+ antigen. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 52:177-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stromberg, N., B. I. Marklund, B. Lund, D. Ilver, A. Hamers, W. Gaastra, K. A. Karlsson, and S. Normark. 1990. Host-specificity of uropathogenic Escherichia coli depends on differences in binding specificity to Galα1-4Gal containing isoreceptors. EMBO J. 9:2001-2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stromqvist, M., and H. Gruffman. 1992. Periodic acid/Schiff staining of glycoproteins immobilized to a blotting matrix. BioTechniques 13:744-749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Symington, F. W., D. L. Hedges, and S. Hakomori. 1985. Glycolipid antigens of human polymorphonuclear neutrophils and the inducible HL-60 myeloid leukemia line. J. Immunol. 134:2498-2506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Gelder, W., M. I. E. Huijskes-Heins, C. J. Hukshorn, C. M. H de Jeu-Jaspers, W. L. van Noort, and H. G. van Eijk. 1995. Isolation, purification and characterization of porcine serum transferrin and hemopexin. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 111B:171-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vliegenthart, J. F. G., and J. Montreuil. 1995. Primary structure of glycoprotein glycans, p. 13-28. In J. Montreuil, H. Schachter, and J. F. G. Vliegenthart (ed.), Glycoproteins. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 58.Willemsen, P. T. J., and F. K. de Graaf. 1992. Age and serotype dependent binding of K88 fimbriae to porcine intestinal receptors. Microb. Pathog. 12:367-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilson, R. A., and D. H. Francis. 1986. Fimbriae and enterotoxins associated with Escherichia coli serogroups isolated from pigs with colibacillosis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 47:213-217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang, H.-J., and S. Hakomori. 1971. A sphingolipid having a novel type of ceramide and lacto-N-fucopentaose III. J. Biol. Chem. 246:1192-1200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]