Abstract

In this paper we describe identification and characterization of Mycobacterium leprae ESAT-6 (L-ESAT-6), the homologue of M. tuberculosis ESAT-6 (T-ESAT-6). T-ESAT-6 is expressed by all pathogenic strains belonging to the M. tuberculosis complex but is absent from virtually all other mycobacterial species, and it is a promising antigen for immunodiagnosis of tuberculosis (TB). Therefore, we analyzed whether L-ESAT-6 is a similarly powerful tool for the study of leprosy by examining T-cell responses against L-ESAT-6 in leprosy patients, TB patients, and exposed or nonexposed healthy controls from areas where leprosy and TB are endemic and areas where they are not endemic. L-ESAT-6 was recognized by T cells from leprosy patients, TB patients, individuals who had contact with TB patients, and healthy individuals from an area where TB and leprosy are endemic but not by T cells from individuals who were not exposed to M. tuberculosis and M. leprae. Moreover, leprosy patients who were not responsive to M. leprae failed to respond to L-ESAT-6. A very similar pattern was obtained with T-ESAT-6. These results show that L-ESAT-6 is a potent M. leprae antigen that stimulates T-cell-dependent gamma interferon production in a large proportion of individuals exposed to M. leprae. Moreover, our results suggest that there is significant cross-reactivity between T-ESAT-6 and L-ESAT-6, which has implications for the use of ESAT-6 as tool for diagnosis of leprosy and TB in areas where both diseases are endemic.

Tuberculosis (TB) and leprosy are major public health problems in the developing world. One-third of the world's population is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and around 2 million individuals suffer from leprosy (9). Many studies have shown that early culture filtrate proteins of M. tuberculosis can be dominant target antigens for CD4+ Th1 cells both in animal models of TB (1, 2, 5, 12, 13) and in humans. One of these secreted antigens, called T-ESAT-6, is a 10-kDa protein which is present in M. tuberculosis and virulent M. bovis but not in M. bovis BCG, and this protein could not be detected in M. leprae, M. avium, M. scrofulaceum, M. intracellulare, M. fortuitum, and M. xenopi (3, 11). Indeed, when the T-ESAT-6 protein was used, TB-infected cattle could be distinguished from cattle sensitized by environmental mycobacteria (15), and in humans T-ESAT-6 and T-ESAT-6-derived peptides were shown to be very efficiently and specifically recognized by individuals exposed to M. tuberculosis (4, 14, 16, 21). The gene for ESAT-6 (Rv3875) is in a region of the M. tuberculosis genome, designated RD1, that is indeed absent from M. bovis BCG and most nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM).

The existing diagnostic skin test reagents for leprosy, lepromin and leprosin, are prepared from whole autoclaved M. leprae and from the soluble fraction of M. leprae, respectively, and contain many mycobacterial antigens shared with other species (20). A more specific skin test reagent for leprosy would be a highly desirable diagnostic tool. Because of the value of T-ESAT-6 in immunodiagnosis of TB, we identified the M. leprae ESAT-6 homologue (L-ESAT-6), and in this paper we report its potent recognition by human T cells from M. leprae- and M. tuberculosis-sensitized individuals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Strain BL21(DE3) was used as a host for pET19b (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) (22) and derivatives of this strain. Bacterial strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium and on Luria-Bertani agar (Difco) supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml).

DNA analysis and sequencing.

λgt11/L45 was sequenced using a T7 sequencing kit (Pharmacia P-L Biochemicals, Milwaukee, Wis.) by the dideoxy chain termination method (17). All primers were synthesized with a Cyclone DNA synthesizer (Biosearch, Bedford, Mass.).

Production of L-ESAT-6 and T-ESAT-6.

Genomic DNA of M. leprae (M. J. Colston) was used as the template for PCR. The PCR product was subcloned into pET19b, and expression was induced by addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Overproduction was harvested after overnight culture at 30°C by centrifugation (5,000 × g; 15 min). The proteins were affinity purified by using Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (10) followed by MonoQ ion exchange, dialyzed (5% acetic acid), and lyophilized. Proteins were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by Coomassie brilliant blue staining.

IFN-γ.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by Ficoll density centrifugation from peripheral blood. PBMC (1.5 × 105 cells/ml) were stimulated in triplicate cultures with antigen in round-bottom 96-well plates. After 6 days, gamma interferon (IFN-γ) levels were determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (sensitivity, 3 pg/ml; UcyTech, Utrecht, The Netherlands). The cutoff value for positive responses was set at 50 pg/ml. M. tuberculosis and M. leprae sonicates were tested at concentrations of 5 μg/ml. The concentration in the negative control (medium) was always less than 20 pg/ml.

ELISPOT assay for single-cell IFN-γ release.

PBMC (1 × 106 cells) were pulsed (16 h) in 48-well plates with antigen (10 μg/ml). Polyvinylidene difluoride-packed 96-well plates (MAIPS45; Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) were precoated with 5 μg of anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody 1-D1K (Mabtech, Stockholm, Sweden) per ml, washed six times with IMDM, and blocked (2 h) with IMDM-10% fetal calf serum. Antigen-pulsed PBMC (2.5 × 106 cells/well; 150 μl) were incubated in the polyvinylidene difluoride-packed 96-well plates at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. After 16 h the plates were washed (phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20), incubated with 100 μl of biotinylated anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody (0.3 μg/ml) for 3 h at room temperature, washed, incubated with streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase conjugate (1:1,000; Mabtech) for 2 h, washed, and incubated with 100 μl of nitroblue tetrazolium-BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate) substrate (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). The reaction was stopped by addition of water. Plates were dried and analyzed with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope and KS ELISPOT software (Carl Zeiss Vision, Hallbergmoos, Germany).

Study subjects.

The study subjects included 49 Dutch individuals; of these, 21 were leprosy patients (4 tuberculoid leprosy/borderline tuberculoid leprosy [TT/BT], 12 BT, 2 BT/borderline leprosy [BT/BB], and 3 borderline lepromatous leprosy [BL]), 10 were TB patients with a history of active TB (6 pulmonary, 1 peritoneal, 1 pleural, 1 lymph node, 1 renal), 7 were healthy individuals who had contact with TB patients, and 11 were healthy controls with no known previous exposure to M. leprae or M. tuberculosis. The leprosy patients had no history of infection with M. tuberculosis. Brazilian leprosy patients (3 BT, 4 BL, 2 lepromatous leprosy [LL]) were recruited from the Leprosy Out-Patient Unit, Leprosy Laboratory, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation. Brazilian TB patients were recruited from the Ambulatory Service, District Hospital Raphael de Paula e Souza, Rio de Janeiro. All individuals gave permission before blood samples were collected and after information was provided, and the study protocol was approved by the LUMC Ethics Committee.

Nucleotide accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of clone L45 reported in this study has been deposited in the EMBL database under accession number X90946.

RESULTS

Identification of the M. leprae ESAT-6 homologue.

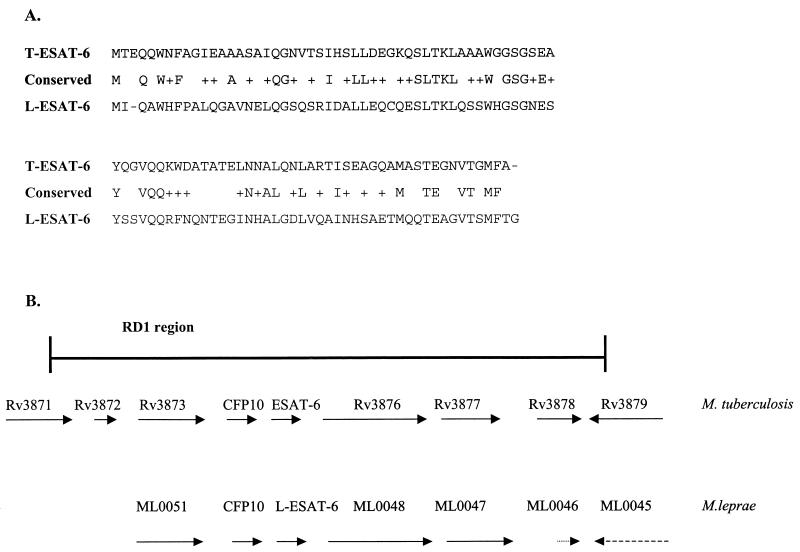

M. leprae inserts expressed in a λgt11 library were identified, as previously described (18), based on their recognition by leprosy patients' sera (18, 23). Sequence analysis of one of the λgt11 clones, designated L45 (accession number X90946), revealed the presence of three potential open reading frames (ORFs) (data not shown) with high levels of similarity to the sequence of M. tuberculosis in the M. tuberculosis-specific RD1 region (14). The first ORF, designated L45 (MLCB628.13c/ML0050), encodes a 100-amino-acid protein with 60% similarity to its M. tuberculosis homologue, CFP10 (Rv3874). The second ORF, designated L-ESAT-6 (MLCB628.12c/ML0049), was homologous to M. tuberculosis ESAT-6 (MTV027.10/Rv3875), with 63% similarity and 36% identity (Fig. 1). The calculated molecular mass (10.46 kDa) and pI (pI 4.91) of L-ESAT-6, which are similar to those of T-ESAT-6 (9.9 kDa and pI 4.21, respectively) (19), further indicate that this ORF encodes the ESAT-6 homologue in M. leprae. The third ORF (MLCB62811c/ML0048) encodes an M. leprae protein with 69% similarity to MTV027.11/Rv3876.

FIG. 1.

(A) Amino acid alignment of L-ESAT-6 and T-ESAT-6 protein sequences. Conserved amino acids are indicated by plus signs. The level of identity between these two ESAT-6 proteins is 36%, and the level of homology is 63%. (B) Genome region of M. leprae and M. tuberculosis in which the ESAT-6 homologue genes are situated.

T-cell recognition of mycobacterial antigens in leprosy patients, TB patients, and healthy controls.

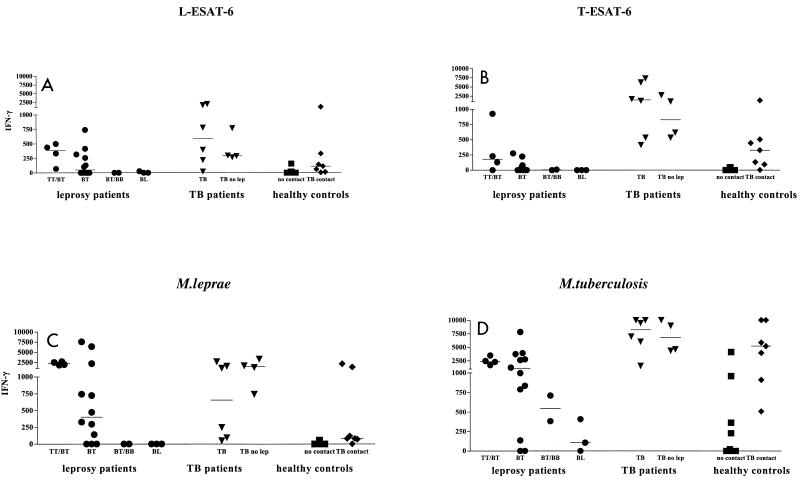

In order to examinewhether M. leprae L-ESAT-6 might be a novel candidate diagnostic tool for leprosy, we evaluated its recognition by T cells in relation to T-ESAT-6. Production of IFN-γ by PBMC in supernatants was assessed in response to L-ESAT-6, T-ESAT-6, M. leprae, and M. tuberculosis for 21 leprosy patients, 10 TB patients, and 11 healthy controls (Fig. 2). Thirteen of the leprosy patients (62%; 4 TT/BT and 9 BT) produced significant amounts of IFN-γ (>50 pg/ml) in response to M. leprae and M. tuberculosis, while five other leprosy patients (1 BT, 2 BT/BB, 2 BL) responded only to M. tuberculosis (Fig. 2). Five leprosy patients who did not respond to M. leprae reacted to M. tuberculosis, most likely as a result of M. tuberculosis exposure. Ten of 13 leprosy patients who responded to M. leprae (77%; 4 TT/BT, 6 BT) responded to L-ESAT-6 (IFN-γ concentration, 70 to 740 pg/ml), and 7 of these patients also responded to T-ESAT-6, although to a somewhat lesser extent. These results thus demonstrate that L-ESAT-6 is a novel antigen that is potently recognized by T cells from leprosy patients.

FIG. 2.

IFN-γ production against L-ESAT-6 (A), T-ESAT-6 (B), M. leprae (C), and M. tuberculosis (D) by PBMC of 21 leprosy patients (•), 10 TB patients, including 4 patients who had no contact with M. leprae (TB no lep) (▾), 11 non-BCG-vaccinated, healthy controls (▪) who had not been exposed to M. leprae or M. tuberculosis, and 7 healthy Dutch individuals who had contact with TB patients (⧫). Median values are indicated by horizontal lines.

In order to investigate whether L-ESAT-6 was recognized uniquely by T cells from leprosy patients, T cells from six TB patients were studied. PBMC from five TB patients responded to M. tuberculosis, M. leprae, and T-ESAT-6 and also to L-ESAT-6. However, since all six TB patients had been in areas where leprosy is endemic, recognition of L-ESAT-6 might have been due to previous exposure to M. leprae. PBMC from four other TB patients, who had never been to areas where leprosy is endemic (Fig. 2), however, also strongly recognized both T-ESAT-6 and L-ESAT-6. Similarly, PBMC from seven healthy individuals who had household contact with Dutch TB patients who had never been in areas where leprosy is endemic also produced IFN-γ in response to both L-ESAT-6 and T-ESAT-6 (Fig. 2). Thus, in these individuals T-cell reactivity against L-ESAT-6 likely resulted from cross-reactivity to T-ESAT-6 due to the amino acid sequence identity and homology of the two ESAT-6 proteins (Fig. 1).

Eleven healthy Dutch individuals with no documented exposure to M. leprae, M. tuberculosis, or BCG failed to produce significant levels of IFN-γ in response to T-ESAT-6, whereas only one showed low IFN-γ production (157 pg/ml) in response to L-ESAT-6 (Fig. 2). Thus, T-cell recognition of T-ESAT-6 and L-ESAT-6 was absent in nonexposed individuals. Four of the healthy individuals responded to M. tuberculosis, which was likely due to BCG vaccination.

IFN-γ production was further quantified by ELISPOT assays, which produced very similar results (Table 1) for PBMC from leprosy patients, TB patients, and healthy controls, again indicating that T-cell cross-reactivity between L-ESAT-6 and T-ESAT-6 is present in leprosy and TB patients.

TABLE 1.

ELISPOT assay for single-cell IFN-γ release

| Group | No. | Medium | Spot-forming cells/106 PBMC

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M. leprae | M. tuberculosis | L-ESAT-6 | T-ESAT-6 | |||

| Leprosy patients | 4 | 4 | 164 | 84 | 88 | 0 |

| 0 | 76 | 180 | 68 | 88 | ||

| 35 | 280 | 120 | 220 | 180 | ||

| 26 | 184 | 176 | 252 | 232 | ||

| TB patients | 3 | 0 | 59 | 160 | 80 | 141 |

| 11 | 10 | 108 | 76 | 43 | ||

| 20 | 265 | 242 | 90 | 215 | ||

| Healthy controls | 2 | 2 | 0 | 80 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 0 | ||

T-cell recognition by leprosy and TB patients and healthy controls in a region where leprosy and TB are endemic.

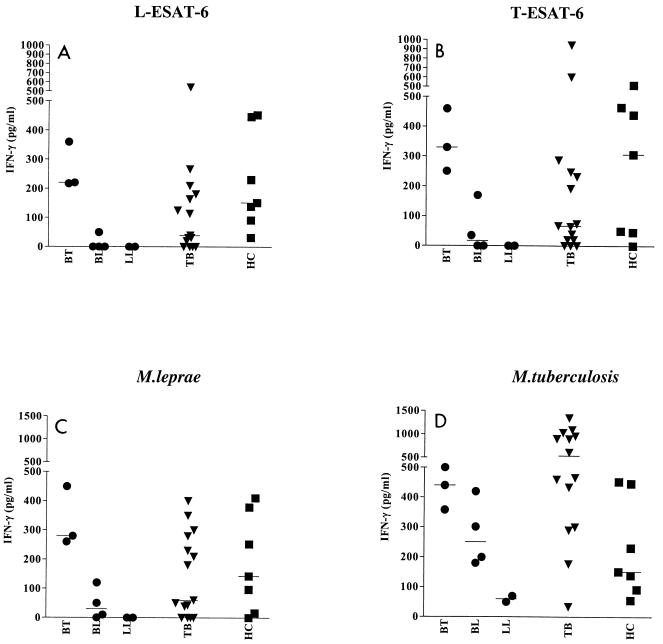

To analyze T-cell recognition of L-ESAT-6 in leprosy and TB patients from an area where leprosy and TB are endemic, the IFN-γ production in PBMC from such patients was compared to that in PBMC from healthy controls from Brazil (Fig. 3). Both ESAT-6 homologues were recognized by leprosy patients (four of nine patients [44%]) and TB patients (9 of 15 patients [60%]), as well as by healthy Brazilian individuals (five of seven individuals [71%]). The responses to M. leprae and M. tuberculosis were similar in all three groups, although M. tuberculosis induced higher IFN-γ production.

FIG. 3.

IFN-γ production by PBMC from Brazilian leprosy patients (•), TB patients (▾), and healthy controls (HC) (▪) in response to L-ESAT-6 (A), T-ESAT-6 (B), M. leprae (C), and M. tuberculosis (D).

DISCUSSION

We identified and characterized the M. leprae ESAT-6 antigen and demonstrated that it is a highly potent T-cell-stimulating antigen, and we provide evidence that this antigen cross-reacts substantially with ESAT-6 of M. tuberculosis at the T-cell level. This has implications for the use of L-ESAT-6 and T-ESAT-6 as diagnostic tools in TB and leprosy.

In contrast to a previous study, which reported the absence of an ESAT-6 homologue in M. leprae (11), we identified the M. leprae ESAT-6 gene. The L-ESAT-6 gene was situated in the same operon as the M. leprae CFP10 gene, which is homologous to the organization of the M. tuberculosis genome (6). The similarity between the L-ESAT-6 and T-ESAT-6 genes and the similarity between their flanking sequences (7, 8) strongly indicate that the L-ESAT-6 genomic region is indeed homologous to RD1 of M. tuberculosis and that L-ESAT-6, therefore, is a homologue of T-ESAT-6 of M. tuberculosis. We analyzed whether L-ESAT-6 is efficiently recognized by T cells, a prerequisite for a diagnostic skin or blood test for leprosy. Our results show that 77% of leprosy patients who responded to M. leprae responded to L-ESAT-6 (Fig. 2) also at the single-cell level (Table 1). Although most leprosy patients also recognize T-ESAT-6, some uniquely respond to L-ESAT-6, suggesting that despite the high level of conservation between the ESAT-6 proteins from M. leprae and M. tuberculosis and the resulting T-cell cross-reactivity, T-cell responses to M. leprae-specific determinants of L-ESAT-6 are also present.

Healthy controls who were not exposed to M. leprae and M. tuberculosis did not respond to L-ESAT-6 or T-ESAT-6, as expected. T-cell reactivity to L-ESAT-6, however, was not observed only with leprosy patients, since PBMC from TB patients or individuals who had contact with TB patients but no known previous exposure to M. leprae also recognized L-ESAT-6 (Fig. 2), strongly suggesting that T-ESAT-6-primed T cells can cross-react with L-ESAT-6. Healthy controls and leprosy and TB patients from an area where TB and leprosy are endemic all recognized L-ESAT-6 with approximately equal efficiencies and frequencies (Fig. 3).

Collectively, these results show that T-cell recognition of L-ESAT-6 comprises both M. leprae-specific and M. leprae-M. tuberculosis cross-reactive T-cell responses (Fig. 2). The T-cell cross-reactivity that we report here is in contrast to the results of a recent study of reactivity towards L-ESAT-6 (19a), which revealed specific recognition of L-ESAT-6 at the antibody level.

In view of the T-cell cross-reactivity between L-ESAT-6 and T-ESAT-6, we attempted to identify potential L-ESAT-6 peptides that might be uniquely recognized by M. leprae-specific T cells. Ten leprosy patients and nine TB patients who responded to L-ESAT-6 were tested for T-cell recognition of overlapping single peptides covering the entire sequence of L-ESAT-6. None of the L-ESAT-6 peptides, however, was uniquely recognized by leprosy patients, since all were recognized by TB patients as well (data not shown).

Thus, a leprosy skin or blood test based on L-ESAT-6 should probably result in low specificity, depending on the proportion of M. tuberculosis-infected individuals in the test population. Because M. tuberculosis infection is less frequent in western countries, specificity would be higher in these areas, but in regions where TB is endemic, where a diagnostic tool for M. leprae infection is most needed, the specificity of L-ESAT-6 as such a tool should be low, since a high proportion of people are latently infected with M. tuberculosis.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Science and Technology for Development program of the European Community (CEC), The Netherlands Leprosy Foundation (NSL), and the Scientific Research for the Tropics (WOTRO) Fund of the Dutch Organization for Scientific Research (NWO).

We thank J. A. C. Nery and A. M. Salles, who were the attending physicians at the Leprosy Out-Patient Unit, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, and A. Milagres and K. S. Cunha for clinical follow-up of TB patients in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Editor: S. H. E. Kaufmann

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen, P. 1994. Effective vaccination of mice against Mycobacterim tuberculosis infection with a soluble mixture of secreted mycobacterial proteins. Infect. Immun. 62:2536-2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen, P. 1994. The T cell response to secreted antigens of M. tuberculosis. Immunobiology 191:537-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen, P., A. B. Andersen, A. L. Sorensen, and S. Nagai. 1995. Recall of long-lived immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. J. Immunol. 154:3359-3372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arend, S. M., P. Andersen, K. E. van Meijgaarden, R. L. V. Skjøt, J. T. van Dissel, and T. H. M. Ottenhoff. 2000. Detection of active tuberculosis infection by T cell responses to early secreted antigen target 6 kDa protein and culture filtrate protein 10. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1850-1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldwin, B. L., C. D'Souza, A. D. Roberts, B. P. Kelly, A. A. Frank, M. A. Lui, J. B. Ulmer, K. Huygen, D. M. McMurray, and I. M. Orme. 1998. Evaluation of new vaccines in the mouse and guinea pig model of tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 66:2951-2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berthet, F. X., P. B. Rasmussen, I. Rosenkrands, P. Andersen, and B. Gicquel. 1998. A Mycobacterium tuberculosis operon encoding ESAT-6 and a novel low-molecular-mass culture filtrate protein (CFP-10). Microbiology 144:3195-3203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole, S. T. 1998. Comparative mycobacterial genomics. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1:567-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole, S. T., K. Eiglmeier, J. Parkhill, K. D. James, N. R. Thomson, P. R. Wheeler, N. Honore, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, K. Mungall, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. M. Davies, K. Devlin, S. Duthoy, T. Feltwell, A. Fraser, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, C. Lacroix, J. Maclean, S. Moule, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, M. A. Quail, M.-A. Rajandream, K. M. Rutherford, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, S. Simon, M. Simmonds, J. Skelton, R. Squares, S. Squares, K. Stevens, K. Taylor, S. Whitehead, J. R. Woodward, and B. G. Barrell. 2001. Massive gene decay in the leprosy bacillus. Nature 409:1007-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dolin, P. J., M. C. Raviglione, and A. Kochi. 1994. Global tuberculosis incidence and mortality during 1990-2000. Bull. W. H. O. 72:213-220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franken, K. L. M. C., H. S. Hiemstra, K. E. van Meijgaarden, Y. Subronto, J. den Hartigh, T. H. M. Ottenhoff, and J. Drijfhout. 2000. Purification of His-tagged proteins by immobilized chelate affinity chromatography (IMAC): the benefits from the use of organic solvent. Protein Express. Purif. 18:95-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harboe, M., T. Oettinger, H. G. Wiker, I. Rosenkrands, and P. Andersen. 1996. Evidence for occurrence of the ESAT-6 protein in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and virulent Mycobacterium bovis and for its absence in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Infect. Immun. 64:16-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haslov, K., A. Andersen, S. Nagai, A. Gottschau, T. Sorensen, and P. Andersen. 1995. Guinea pig cellular immune responses to proteins secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 63:804-810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horwitz, M. A., B.-W. E. Lee, B. J. Dillon, and G. Harth. 1995. Protective immunity against tuberculosis induced by vaccination with major extracellular proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1530-1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Philipp, W. J., S. Poulet, K. Eiglmeier, L. Pascopella, V. Balasubramanian, B. Heym, S. Bergh, B. R. Bloom, W. R. Jacobs, and S. T. Cole. 1996. An integrated map of the genome of the tubercle bacillus, M. tuberculosis H37Rv, and comparison with M. leprae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:3132-3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollock, J. M., and P. Andersen. 1997. The potential of the T-ESAT-6 antigen secreted by virulent mycobacteria for specific diagnosis of tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 175:1251-1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ravn, P., A. Demissie, T. Eguale, H. Wondwosson, D. Lein, H. Amoudy, A. S. Mustafa, A. K. Jensen, A. Holm, I. Rosenkrands, F. Oftung, J. Olobo, C. F. von-Reyn, and P. Andersen. 1999. Human T cell responses to the T-ESAT-6 antigen from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 179:637-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. R. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sathish, M., R. E. Esser, J. E. R. Thole, and J. E. Clark Curtiss. 1990. Identification and characterization of antigenic determinants of Mycobacterium leprae that react with antibodies in sera of leprosy patients. Infect. Immun. 58:1327-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19a.Spencer, J. S., M. A. M. Marques, M. C. B. S. Lima, A. P. Junqueira-Kipnis, B. C. Gregory, R. W. Truman, and P. J. Brennan. 2002. Antigenic specificity of the Mycobacterium leprae homologue of ESAT-6. Infect. Immun. 70:1010-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorensen, A. L., S. Nagai, G. Houen, P. Andersen, and A. B. Andersen. 1995. Purification and characterization of a low-molecular-mass T-cell antigen secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 63:1710-1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas, J., M. Joseph, K. Ramanujam, C. J. G. Chacko, and C. K. Job. 1980. The histology of the Mitsuda reaction and its significance. Lepr. Rev. 51:329-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ulrichs, T., P. Anding, S. Porcelli, S. H. E. Kaufmann, and M. E. Munk. 2000. Increased numbers of ESAT-6 and purified protein derivative-specific gamma interferon-producing cells in subclinical and active tuberculosis infection. Infect. Immun. 68:6073-6076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young, D. B., S. H. Kaufmann, P. W. Hermans, and J. E. R. Thole. 1992. Mycobacterial protein antigens: a compilation. Mol. Microbiol. 6:133-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]