Abstract

A major virulence factor of Porphyromonas gingivalis is the extracellular noncovalently associated complexes of Arg-X- and Lys-X-specific cysteine proteinases and adhesins designated the RgpA-Kgp complexes. In this study we investigated the ability of RgpA-Kgp as an immunogen to protect against P. gingivalis-induced periodontal bone loss in the rat. Specific-pathogen-free Sprague-Dawley rats were immunized with either formalin-killed whole P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 cells with incomplete Freund's adjuvant, RgpA-Kgp with incomplete Freund's adjuvant, or incomplete Freund's adjuvant alone. The animals were then challenged by oral inoculation with live P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 cells. Marked periodontal bone loss was observed in animals immunized with incomplete Freund's adjuvant alone; this bone loss was significantly (P < 0.05) greater than that detected in animals immunized with formalin-killed whole cells or RgpA-Kgp or in unchallenged animals. There was no significant difference in periodontal bone loss between animals immunized with formalin-killed whole cells and those immunized with RgpA-Kgp. The bone loss in these animals was also not significantly different from that in unchallenged animals. DNA probe analysis of subgingival plaque samples showed that 100% of the animals immunized with incomplete Freund's adjuvant alone and challenged with P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 were positive for the bacterium. However, P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 could not be detected in subgingival plaque samples from animals immunized with formalin-killed whole cells or with RgpA-Kgp. Immunization with formalin-killed whole cells or RgpA-Kgp induced a high-titer serum immunoglobulin G2a response. Western blot analysis of RgpA-Kgp using pooled protective antisera taken from rats immunized with RgpA-Kgp revealed immunodominant bands at 44, 39, and 27 kDa. In conclusion, immunization with RgpA-Kgp restricted colonization by P. gingivalis and periodontal bone loss in the rat.

Periodontitis is a destructive inflammatory disease of the supporting tissues of the teeth associated with subgingival infection by a consortium of gram-negative bacteria and is a major cause of tooth loss in adults (35). The current treatment of periodontitis is nonspecific and is centered on the removal of subgingival plaque by mechanical debridement often involving surgical procedures. This ongoing therapy is costly and painful and has a variable prognosis. Porphyromonas gingivalis is now considered to be a major periodontal pathogen as it is closely associated with chronic periodontitis in humans (25, 47-49), and its subgingival implantation in mice (1) rats (11, 20), and nonhuman primates (17, 36) is associated with initiation and progression of disease. The elucidation of a specific bacterial etiology for chronic periodontitis suggests that the development of a specific treatment modality to target the sites of colonization or the virulence of P. gingivalis and other periodontal pathogens is now a more rational approach to treat the disease. In the nonhuman primate model, immunization with killed whole P. gingivalis cells significantly reduced progression of periodontitis associated with the indigenous microflora, as well as with superinfection by P. gingivalis (36). Furthermore, immunization with P. gingivalis whole cells has similarly been shown to reduce periodontal bone loss in the rat periodontitis model (11). These animal data therefore support the utility of a specific and defined P. gingivalis vaccine in the adjunctive treatment of human chronic periodontitis. Vaccination could become an important adjunctive therapy to scaling and root planing (mechanical debridement) to help prevent site recolonization by P. gingivalis and/or restrict the further progression of disease by blocking the penetration of the major antigens associated with virulence into the gingival tissues. Besides blocking these antigens, the antibodies, if directed to key epitopes involved in function, may neutralize their action and also facilitate their removal through opsonization and phagocytosis. Furthermore, specific antibodies of a certain subclass (e.g., immunoglobulin A [IgA] and IgG4 in humans) may reduce inflammation associated with chronic bacterial infections at mucosal sites (10, 12, 33, 53). In the development of a defined and specific vaccine it is therefore essential to identify key virulence factors of the pathogen to which the host immune response should be directed.

The pathogenicity of P. gingivalis has been attributed to a number of virulence factors such as fimbriae (6), hemagglutinins (15, 19), lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (16), and the Arg-X- and Lys-X-specific cysteine proteinases and their associated adhesins (25, 33, 55). The Arg-X- and Lys-X-specific cysteine proteinases are believed to play a major role in the pathogenesis of periodontitis by degrading a variety of host proteins, by dysregulating the host defenses, and by inducing proinflammatory cytokines involved in tissue destruction and alveolar bone resorption. (33, 34, 55). Three genes encode the major extracellular Arg-X- and Lys-X-specific cysteine proteinases of P. gingivalis: rgpA, rgpB, and kgp (7). The proteins encoded by rgpA and kgp of P. gingivalis strain W50 have been characterized as cell-associated complexes of noncovalently associated proteinases and adhesins, designated the RgpA-Kgp proteinase-adhesin complexes, formerly the PrtR-PrtK proteinase-adhesin complexes (2). The RgpA-Kgp complexes of P. gingivalis strain W50 are composed of a 45-kDa Arg-X-specific proteinase (RgpA45) associated with four sequence-related adhesins, RgpA44, RgpA15, RgpA17, and RgpA27, all encoded by rgpA (2). The RgpA-Kgp complexes are also characterized by a 48-kDa Lys-specific proteinase (Kgp48) associated with sequence-related adhesins Kgp39, Kgp15, and Kgp44, all encoded by kgp (45). A second Arg-specific cysteine proteinase, structurally very similar to RgpA45, has also been characterized and is encoded by rgpB (44). This proteinase is present as an LPS-modified, 70- to 80-kDa, membrane-associated form and as a discrete 50-kDa proteinase in the culture supernatant (33, 37, 44). RgpB is not found associated with adhesins, and the rpgB gene lacks the adhesin binding motif that is present in the RgpA and Kgp catalytic domains (44). This adhesin binding motif is also present in some of the adhesin domains of RgpA and Kgp and is proposed to be responsible for the incorporation of the RgpA45 and Kgp48 catalytic domains into non-covalently associated complexes with adhesins and for the autoaggregation of the adhesins into complexes (44). A similar adhesin binding motif is also found in a P. gingivalis hemagglutinin (HagA), which also autoaggregates (15, 43).

P. gingivalis mutants with reduced Arg-X and Lys-X proteinase activity and wild-type cells treated with a proteinase inhibitor have been reported to exhibit reduced virulence in animal models (21, 29). An isogenic mutant lacking RgpA, RgpB, and Kgp was reported not to agglutinate erythrocytes, bind to hemoglobin, or grow in defined medium containing protein as the sole carbon and energy source (42). Using the murine lesion model, we have shown that the purified RgpA-Kgp complexes, when used as an immunogen, were as effective as formalin-killed whole cells (FKWC) in conferring protection against subcutaneous challenge with P. gingivalis strains ATCC 33277 and W50 (33). These results therefore suggest that RgpA-Kgp may be an efficacious vaccine against P. gingivalis-induced periodontitis. The aim of this paper, therefore, was to determine the efficacy of RgpA-Kgp, when used as a vaccine, to protect against periodontal bone loss induced by P. gingivalis in the rat model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and preparation of inocula.

P. gingivalis strains ATCC 53978 (W50) and ATCC 33277, used in this study, have been described previously (33). Bacterial strains were stored at room temperature as lyophilized cultures. Both strains were cultured and maintained on horse blood agar (HBA) plates containing 10% (vol/vol) lysed horse blood and 1 mg of menadione (Sigma)/liter at 37°C in an anaerobic chamber (MK3 anaerobic work station; Don Whitley Scientific Ltd., Shipley, England) with an atmosphere of 80% N2-10% CO2-10% H2.

Three- to five-day-old P. gingivalis W50 or P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 cells derived from passages 3 to 6 were used to inoculate brain heart infusion broth enriched with hemin (15 μg/ml), menadione (1 μg/ml), and filter-sterilized cysteine-HCl (0.5 g/liter) at 37°C. Final cultures were grown to late exponential phase corresponding to a 0.18 optical density measured at 650 nm with a spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer; 295E). Purity of cultures was assessed by Gram staining and determination of colonial morphology. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g (JA 10 rotor, J2-21 M/E; Beckman, Palo Alto, Calif.) for 30 min at 4°C. After the supernatant was carefully removed from the anaerobic chamber, the cell pellets were resuspended in previously cooled (4°C) and prereduced PG buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgSO4, 0.5 g of cysteine/liter, pH 7.8) containing 5% (wt/vol) low-viscosity carboxymethyl cellulose. The volume was adjusted to give a final concentration of 2.5 × 1011 CFU/ml, and the cell suspensions were divided into 2-ml aliquots in syringes for inoculation into animals.

Preparation of P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 FKWC.

Cells were treated overnight with equal volumes of 0.5% (vol/vol) formal saline on a rocking platform. Sterile PG buffer (equivalent to 10 times the volume of treated cells) was then added and the mixture was centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 × g. The supernatant was removed, and the cell pellet was resuspended gently in PG buffer (20 times the volume of the cell pellet) and centrifuged again for 10 min at 10,000 × g. After the supernatant was discarded, the cells were resuspended in sterile PG buffer to obtain a concentration of 1010 CFU in 0.1 ml. For immunization, the cell suspension was mixed with incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA) at a ratio of 1:1 (vol/vol).

Preparation and analysis of the RgpA-Kgp proteinase adhesin complexes.

The RgpA-Kgp complexes were prepared from a P. gingivalis W50 cell sonicate by anion exchange, gel filtration, and Arg-Sepharose chromatography as described by Bhogal et al. (2). The purified RgpA-Kgp adhesin complexes were characterized by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (24) and blotting onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, followed by N-terminal sequence analysis as described by Bhogal et al. (2). Protein concentrations of samples were determined using the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.). Proteolytic activity of samples was determined using synthetic chromogenic substrates as described by Bhogal et al. (2).

Rat periodontitis model.

The rat periodontitis model experiments were approved by the University of Melbourne Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation. Specific-pathogen-free, male Sprague-Dawley rats were divided randomly into groups of 10 rats and maintained in wire-bottom cages in order to reduce the influence of bedding and hair impaction on alveolar bone loss. At the commencement of the experiment, plaque samples were taken from all rats and were immediately cultured on HBA plates with 400 μg of kanamycin/ml. All animals were negative for black-pigmented organisms. At the age of 4 weeks, rats were immunized by subcutaneous injection of an emulsion of immunogen and IFA at 1:1 (vol/vol). Each rat received 0.2 ml in the scruff of the neck. Group 1 rats were immunized with FKWC of P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 (1010 cells/dose); group 2 rats were immunized with RgpA-Kgp (100 μg/dose); group 3 and 4 rats were sham immunized with IFA only. All immunizations were repeated 3 weeks after the first immunization with the same dose, except for RgpA-Kgp (group 2), where the second dose consisted of 60 μg/dose. One week after the second immunization each animal was bled from the tail, and sera were stored at −70°C.

On the 19th day after immunization, all rats were treated with antibiotics for three consecutive days to suppress the endogenous microflora. Each rat received a daily dose of 20 mg each of ampicillin and kanamycin in 0.5 ml of 5% (wt/vol) carboxymethyl cellulose in water. On the 25th day, all animals in groups 1, 2, and 3 were challenged with P. gingivalis ATCC 33277. This was repeated four times at 48-h intervals. Group 4 was left unchallenged. The animals were challenged by inoculation using a 2.5-ml disposable syringe fitted with a 16-gauge gavage tube as described previously (22). A 1-ml sample of the P. gingivalis cell suspension was inoculated into each animal in the following manner: 0.75 ml was gavaged into animals by inserting the tube into the pharynx, 0.2 ml was deposited in the molar gingival area (50 μl per quadrant), and 50 μl was deposited in the colorectal area. Six weeks after the last inoculation, animals were anesthetized with 1:1 Rompen and ketamine and samples of subgingival plaque and saliva were taken and animals were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation. The maxilla and mandible were dissected from the skull and stored at −20°C. The rat jaws were thawed, boiled for 5 min, and defleshed with a periodontal scaler. The two sides of each maxilla (excluding premaxilla) were separated along the midline suture. They were left overnight in 3% (vol/vol) H2O2, air dried, and stained for 1 min in an aqueous solution of 0.1% (wt/vol) methylene blue to delineate the cementoenamel junction. The jaws were coded, and an investigator unfamiliar with the code measured horizontal bone loss using the morphometric method of Klausen et al. (22, 23). Bone loss data were statistically analyzed by a one-way classification analysis of variance with a post hoc Scheffe multiple comparison (M. Norusis, SPSS for Windows: base system user's guide, release 6.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill., 1993).

Plaque sampling.

Plaque samples were taken between inoculations with extra-fine paper points and immediately cultured on HBA plates with 400 μg of kanamycin/ml. All inoculated animals were positive for P. gingivalis. At the end of the experiment, after the animals were anesthetized, subgingival plaque was removed from the first and second molars with a sterile Naber's probe and pooled in 200 μl of 10 mM NaOH-20 mM EGTA-0.3% (wt/vol) SDS, vortexed vigorously, and then stored at −70°C until DNA probe analysis.

Collection of saliva.

Subcutaneous injection of pilocarpine nitrate (3 to 5 mg/kg of body weight) was given in the scruff of the neck for parasympathetic stimulation. Saliva was collected by a method described by Reynolds and Del Rio (38). The saliva was collected in a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube containing 20 μl of a cocktail of proteinase inhibitors at 1 mg/ml (Complete; Boehringer Mannheim, Nunawading, Victoria, Australia). The samples of saliva were kept on ice until clarified by centrifugation at 5,000 × g, 4°C, for 20 min. The supernatants were stored at −70°C until required.

DNA probe analysis of plaque samples.

Plaque samples in 10 mM NaOH-20 mM EGTA-0.3% (wt/vol) SDS were boiled for 10 min, and 200 μl of double-distilled water was added. An equal volume of phenol-chloroform was added, and the solution was mixed briefly with a vortex mixer and centrifuged for 3 min at 13,000 × g. The aqueous phase was removed carefully, and phenol-chloroform extraction was repeated. DNA was precipitated from the aqueous phase by adding 20 μl (1/10 volume) of 3 M sodium acetate and 500 μl of ethanol. DNA was pelleted by centrifugation for 15 min at 13,000 × g and allowed to air dry. The pelleted DNA was washed with 70% (vol/vol) ethanol and resuspended in 200 μl of 0.4 N NaOH and used for dot blotting. The dot blot apparatus (Schleicher & Schuell Minifold I dot blot system; Bartelt Instruments, Pty. Ltd., Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) was prewarmed at 37°C. Under gentle suction DNA in 0.4 N NaOH was applied to a Hybond N+ membrane (Amersham Corp.) and subsequently washed through under suction with prewarmed (37°C) 0.4 N NaOH. The membrane was rinsed briefly for 3 min with 10% (wt/vol) SDS and then treated for a further 10 min with a solution of 1.5 M NaCl and 0.5 M NaOH before being neutralized for 10 min with a solution of 1.5 M NaCl, 0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, and 1 mM EDTA. After being rinsed in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 15 mM sodium citrate, pH 8.0, plus 150 mM NaCl) the membrane was incubated in a solution of pronase E (100 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C. The membrane was then incubated in a solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1% (wt/vol) SDS for 30 min at 50°C and then prehybridized at 65°C for 1 h in Church buffer (0.5 M sodium phosphate [pH 7.2], 1 mM EDTA, 7% [wt/vol] SDS). The membrane was then hybridized overnight at 65°C with a P. gingivalis IS1126 (28) DNA probe in Church buffer. The P. gingivalis IS1126 DNA probe was prepared by PCR amplification of P. gingivalis genomic DNA (46) using primer sequences 5′-CGGCGATTGGCGTATATTTTGTTT-3′ and 5′-AAAATAAGGAGATGGAGGGAAGAG-3′ to amplify from base 13 to base 1325. The probe was radiolabeled using the Prime-a-Gene labeling system (Boehringer Mannheim). The membrane was washed at 65°C in 0.5× SSC containing 0.1% (wt/vol) SDS for 1 h. Membranes were exposed to a Fuji BAS-MP 2040S imaging plate for 4 h before analysis using a Fuji Fujix BAS1000 scanner. Individual samples were quantified with the PCBAS program. Streptococcus mutans DNA was used as a negative control, while 10-fold serial dilutions of P. gingivalis genomic DNA were used for standardization.

Analysis of specific antibodies in rat serum and saliva samples by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Microtiter plates were coated with RgpA-Kgp at 1 μg/ml or FKWC at 1010 cells/ml in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4-200 mM NaCl (TBS). The microtiter plates were sealed and kept in a humidified chamber overnight at 4°C. Plates were then washed three times with TBS containing 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (TBST), and wells were coated with 200 μl of blocking solution containing 2% (wt/vol) gelatin in TBST, sealed, and then incubated at 37°C for 2 h. After three washes with TBST, 50 μl of serially diluted rat sera in antibody-diluting buffer (TBS with 1% gelatin) was added to each well. Control wells received antibody-diluting buffer only. The plates were sealed and incubated for 90 min at 37°C. Following incubation the plates were washed three times with TBST and 50 μl of a secondary antibody (diluted 1:3,000) was placed in appropriate wells. The secondary antibodies used were biotinylated mouse anti-rat IgG, IgA, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, or IgG2c. Antibody-diluting buffer only was placed in wells not receiving a secondary antibody. The plates were sealed and incubated at 37°C for 60 min. The plates were then washed three times, and 50 μl of avidin-peroxidase at a dilution of 1/50,000 was placed in all wells except one control series, which received only antibody-diluting buffer. The plates were sealed and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After being washed five times with TBST each well received 100 μl of the color development solution, containing 10 mg of 3,3′,5,5′,-tetramethylbenzidine/ml dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, diluted 1/100 in sodium acetate-citric acid buffer, pH 6.0, containing 0.004% (vol/vol) hydrogen peroxide. The incubation was carried out at room temperature (25°C) in the dark. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 40 μl of 2 M H2SO4 per well to produce a final volume of 140 μl. The absorbance values for each plate were measured with a 450-nm filter in a plate reader (Bio-Rad; microplate reader model 450).

Western blot analysis of RgpA-Kgp proteinase-adhesin complex using rat protective sera.

RgpA-Kgp (30 μg) was subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in gels of 12.5% (wt/vol) acrylamide (1 mm thick) and then electrophoretically transferred onto a polyvinylidine difluoride membrane as described above. After the membrane was sectioned in half, one half was stained with 0.1% (wt/vol) methylene blue. The other half was blocked with nonfat skimmed milk powder in TN buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 100 mM NaCl) for 2 h at room temperature (20°C). The membranes were then incubated with pooled RgpA-Kgp-immunized rat serum diluted (1/25) in TN buffer. After overnight incubation at 4°C the membranes were washed four times (10 min each) with TN buffer containing 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20. The membranes were then incubated for 2 h at 20°C with rabbit anti-rat horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG (1/200 dilution). The membranes were washed four times with TN buffer containing 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20, and the bound antibody was detected with 0.005% (wt/vol) 4-chloro-1-naphthol in TN buffer containing 16.6% (vol/vol) methanol and 0.015% (vol/vol) H2O2.

RESULTS

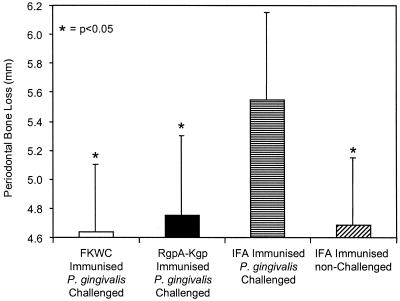

Rats were immunized with either RgpA-Kgp complexes in IFA, P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 FKWC in IFA, or IFA alone and then challenged with live P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 cells. In the IFA-immunized, challenged animals there was marked periodontal bone loss, which was significantly greater (P < 0.05) than that detected in the animals immunized with FKWC or RgpA-Kgp or in animals unchallenged (Fig. 1). There was no significant difference in periodontal bone loss between animals immunized with FKWC or RgpA-Kgp and sham-immunized, unchallenged animals (Fig. 1). DNA probe analysis showed that 100% of the animals sham immunized with IFA and challenged with P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 were positive for the bacterium with 2.6 × 104 ± 2.2 × 104 P. gingivalis cells detected per subgingival plaque sample. However, P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 DNA could not be detected in subgingival plaque samples taken from animals immunized with FKWC or RgpA-Kgp or from animals not challenged with P. gingivalis ATCC 33277.

FIG. 1.

Effect of immunization with either P. gingivalis FKWC or RgpA-Kgp on P. gingivalis-induced bone loss in the rat periodontitis model. Each value represents the mean ± standard deviation (n = 20).

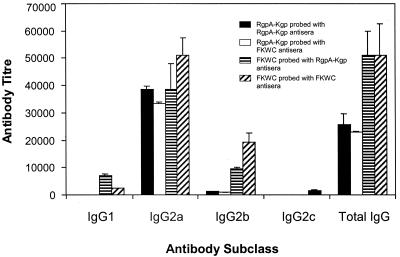

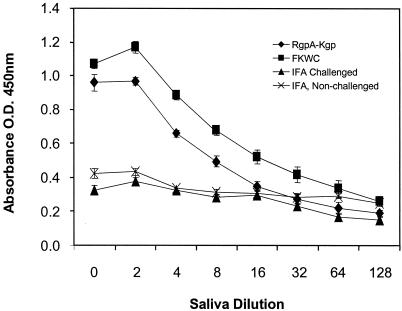

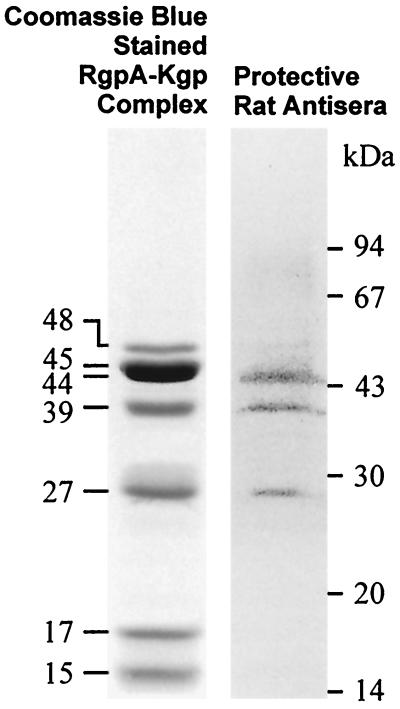

Postimmunization and before challenge with live P. gingivalis cells, animals were bled and serum antibody titers were determined. Immunization with FKWC or RgpA-Kgp induced a high-titer serum IgG response to the immunogens (Fig. 2). The predominant serum IgG subclass each immunogen induced was IgG2a (Fig. 2). The high-titer IgG2a responses for immunogens FKWC and RgpA-Kgp were similar. Saliva sampled from animals immunized with RgpA-Kgp or FKWC and challenged with live P. gingivalis contained IgA specific for FKWC (Fig. 3). However, saliva from animals sham immunized with IFA and challenged with live P. gingivalis did not contain specific IgA antibodies to FKWC (Fig. 3). Western blot analysis of RgpA-Kgp using pooled protective antisera taken from rats immunized with RgpA-Kgp revealed immunodominant bands at 44, 39, and 27 kDa (Fig. 4).

FIG. 2.

Antigen-specific IgG and subclass antibody titer in sera of rats immunized with either FKWC or RgpA-Kgp. Antibody titers are expressed as the dilution factor which produced an absorbance fivefold greater than background in the ELISA. Each value represents the mean ± standard deviation.

FIG. 3.

Salivary IgA response to FKWC in rats immunized with RgpA-Kgp or FKWC. O.D., optical density. Each value represents the mean ± standard deviation.

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis of RgpA-Kgp using protective anti-RgpA-Kgp pooled antisera.

DISCUSSION

The results presented in this study demonstrate that immunization of rats with RgpA-Kgp of P. gingivalis W50 protected against challenge with P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 in the rat periodontitis model. These results confirm and extend those of Gibson and Genco (14), who showed that immunization with RgpA, but not RgpB, protected against P. gingivalis-mediated periodontal bone loss in the murine model. The animals immunized with RgpA-Kgp in the present study showed no greater bone loss than unchallenged animals or animals immunized with FKWC. Immunization with FKWC or RgpA-Kgp restricted P. gingivalis colonization of the subgingival crevice, as the bacterium could not be detected in supragingival plaque samples of immunized animals by DNA probe analysis. Both FKWC and RgpA-Kgp, when used as immunogens, induced a high-titer serum IgG2a response. The cross-reactivity of the antibodies induced and the similarity in titers suggest that RgpA-Kgp is a major immunogen on the surface of P. gingivalis. This result is consistent with the work of Genco et al. (13), who have shown using a competitive ELISA that 42 and 53% of the antibodies induced by immunization of mice with heat-killed P. gingivalis cells recognized RgpA and Kgp, respectively. These authors also showed that, even at high concentrations, RgpB, which is structurally very similar (97% sequence identity) to the catalytic domain of RgpA, did not inhibit antibody binding to P. gingivalis, indicating that the antibodies bound to the adhesin domains of RgpA. Using Western blot analysis Genco et al. (13) demonstrated that the 44-kDa adhesin/hemagglutinin (RgpA44) and the 27-kDa adhesin (RgpA27) of RgpA and the 39- or 42-kDa adhesin (Kgp39) of Kgp, among others, were recognized by anti-RgpA antisera. These results are consistent with the Western blot analysis of RgpA-Kgp in the present study using the protective rat anti-RgpA-Kgp antisera, which recognized 44-, 39-, and 27-kDa adhesins of the RgpA-Kgp complexes (Fig. 4) (2). Similarly, Yonezawa et al. (59) have recently shown that a DNA vaccine carrying rgpA induced antibodies that recognized RgpA44, RgpA27, and Kgp39, among others, in a P. gingivalis cell sonicate and inhibited cell hemagglutination activity and binding to type I collagen.

Using the murine lesion model we have recently shown that RgpA-Kgp, when used as an immunogen, conferred protection against subcutaneous challenge with P. gingivalis strains ATCC 33277 and W50 (33). In that study RgpA-Kgp was as effective as FKWC, when used as an immunogen, in conferring protection. Western blot analysis of RgpA-Kgp with the protective antisera revealed that only three bands at 27, 39, and 44 kDa were strongly recognized by the antibodies, which is identical to the results obtained in the present study with the rat protective sera. Epitope mapping of the RgpA27 adhesin with the protective antisera in the previous study (33) identified two major epitopes, with one epitope (EP1) being common to RgpA44, RgpA27, and Kgp39. Peptides that corresponded to adhesin sequences involved in aggregation and binding to host substrates were also synthesized (33, 39). Three of these adhesin peptides conjugated to diphtheria toxoid conferred protection as vaccines in the murine lesion model (33). The three protective adhesin peptide sequences and the EP1 epitope sequence all exist within a 135-residue span (RgpA44 residues 831 to 965, numbering from the initial Met) in the RgpA44 and Kgp39 adhesins of RgpA-Kgp. Motifs within this 135-residue span are involved in aggregation (44), hemagglutination (43), and binding to host substrates (33, 39; N. M. O’Brien-Simpson et al., unpublished data). A monoclonal antibody that binds within this span (RgpA44 residues 907 to 931) has been demonstrated to restrict colonization of P. gingivalis in the human oral cavity (4). Therefore, the rat protective antisera in the present study, which also bound to the RgpA44, Kgp39, and RgpA27 adhesins of RgpA-Kgp, may block colonization, hemagglutination, and the formation and substrate targeting of the proteinase-adhesin complex, thereby substantially reducing the virulence of P. gingivalis and restricting colonization of the subgingival crevice.

Specific salivary IgA antibodies against FKWC were detected in animals immunized with FKWC or RgpA-Kgp but not in sham-immunized, challenged animals. This result may indicate that immunization primed B cells for IgA production and that P. gingivalis challenge may have stimulated the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue via Th2 cytokines to mature surface IgA+ B cells into IgA-secreting cells (26) to produce secretory IgA in saliva. The major antibody induced by immunization with FKWC and RgpA-Kgp was serum IgG2a, and this subclass is representative of a predominant Th2 response (8, 57). A predominant IgG2a antigen-specific subclass response has been reported for rats immunized with Bordetella pertussis vaccine and antigens from nematode Nippostrongylus brasilienesis (9, 58, 60). Furthermore, rat IgG2a has been reported to protect mucosal surfaces against infection similarly to IgA (40, 56). Rat IgG2a-opsonized antigen induces phagocytosis and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in macrophages and natural killer cells via FcγRII receptors (30, 51). Rat IgG2a has also been reported to inhibit mucosal mast cell degranulation while triggering phagocytosis and endocytosis (3).

It is expected that the specific IgG2a antibodies directed against the adhesin epitopes of RgpA-Kgp would be present in the gingival tissues and in gingival crevicular fluid. However, these antibodies may also be present in saliva, as mice parenterally vaccinated have been reported to secrete antigen-specific IgG antibodies in saliva (5, 52). The presence in gingival crevicular fluid and saliva of the specific antibodies against the substrate-binding adhesins of RgpA-Kgp may have blocked adherence and subsequent colonization of P. gingivalis in the oral cavity, explaining the lack of detection of the bacterium by DNA probe analysis in subgingival plaque samples from immunized animals. Furthermore, the presence of the specific IgG2a antibodies in the gingival tissues may have also blocked penetration of RgpA-Kgp, which is a major virulence factor for the bacterium, either as discrete complexes or on the surface of outer membrane vesicles. The opsonization of RgpA-Kgp, outer membrane vesicles, or invading cells by the specific IgG2a antibodies would have facilitated Fc receptor-dependent phagocytosis with perhaps little induction of proinflammatory cytokines. These proposed mechanisms of protection may therefore explain why immunization with RgpA-Kgp was so effective in preventing P. gingivalis-induced periodontal bone loss.

Other investigators have demonstrated some protection against periodontal bone loss in the rat periodontitis model upon immunization with a purified or recombinant P. gingivalis fimbrial protein or with a commensal bacterium expressing biologically active domains of the fimbrial protein (11, 41). In a recent study by Sharma et al. (41) oral immunization of rats with Streptococcus gordonii expressing domains of the P. gingivalis fimbrial protein (FimA) induced FimA-specific serum (IgG and IgA) and salivary (IgA) antibodies. The immunization resulted in partial (60%) protection against P. gingivalis-induced periodontal bone loss. This result can perhaps be explained by the nature of the antigen employed, as FimA is not essential for virulence of the bacterium. P. gingivalis strains W50 and W83, which do not express the FimA protein (27, 50, 54), are highly virulent and invasive in animal models (32).

We recently examined sera from 25 chronic periodontitis patients (diseased group) and 25 age- and sex-matched controls (control group) for IgG and subclass responses to RgpA-Kgp (32). The level of P. gingivalis in subgingival plaque samples was determined with a DNA probe, and significant positive correlations between the percentage of sites positive for P. gingivalis and measures of disease severity (mean pocket depth, mean attachment loss, and percentage of sites that bled on probing) were found. The diseased group had significantly higher specific IgG responses to RgpA-Kgp than did the control group, and the responses were significantly associated with mean probing depths and percentage of sites positive for P. gingivalis. Analysis of the IgG subclass responses to RgpA-Kgp revealed that the subclass distribution for both the diseased and control groups was IgG4 > IgG2 > IgG3 = IgG1. However, as disease severity increased there was a concomitant increase in the IgG2 response and a decrease in the IgG4 response to RgpA-Kgp. Furthermore, sera from individuals who exhibited low levels of periodontitis with high-IgG4 and low-IgG2 responses reacted with the RgpA27, Kgp39, and RgpA44 adhesins in a Western blot as well as with major epitope EP1 in an ELISA. However, sera from diseased subjects reacted with the RgpA44/Kgp44 adhesin only and did not recognize EP1. Unlike other subclass antibodies, IgG4 (equivalent to IgG1 and IgG2a in rats) is considered to have a noninflammatory effector function profile, as it does not bind or activate complement, and a suggested biological function for IgG4 is a protective or defensive role in mucosal immunity (18, 31). Furthermore, IgG4 has been shown to bind Fc receptor FcγR1, inducing phagocytosis and production of interleukin-10, which reverses the proinflammatory response of macrophages to bacteria or bacterial products such as LPS (10, 12, 53). These data along with our animal data suggest that a predominant Th2 antibody response (IgG4 and IgA in humans) directed against the substrate binding motifs of the Kgp39 and RgpA44 adhesins may prevent or reduce disease. Therefore immunization with RgpA-Kgp may provide an important adjunctive therapy to the treatment of chronic periodontitis in humans.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that immunization with RgpA-Kgp of P. gingivalis restricts colonization of the subgingival crevice by P. gingivalis and subsequent periodontal bone loss in the rat periodontitis model.

Editor: R. N. Moore

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker, P. J., R. T. Evans, and D. C. Roopenian. 1994. Oral infection with Porphyromonas gingivalis and induced alveolar bone loss in immunocompetent and severe combined immunodeficient mice. Arch. Oral Biol. 39:1035-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhogal, P. S., N. Slakeski, and E. C. Reynolds. 1997. A cell associated protein complex of Porphyromonas gingivalis W50 composed of Arg- and Lys-specific cysteine proteinases and adhesins. Microbiology 143:2485-2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bocek, P., Jr., L. Draberova, P. Draber, and I. Pecht. 1995. Characterization of Fc gamma receptors on rat mucosal mast cells using a mutant Fc epsilon RI-deficient rat basophilic leukemia line. Eur. J. Immunol. 25:2948-2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Booth, V., F. P. Ashley, and T. Lehner. 1996. Passive immunization with monoclonal antibodies against Porphyromonas gingivalis in patients with periodontitis. Infect. Immun. 64:422-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cartry, O., P. Moja, A. Quesnel, B. Pozzetto, F. R. Lucht, and C. Genin. 1997. Quantification of IgA and IgG and specificities of antibodies to viral proteins in parotid saliva at different stages of HIV-1 infection. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 109:47-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandad, F., and C. Mouton. 1995. Antigenic, structural, and functional relationships between fimbriae and the hemagglutinating adhesin HA-Ag2 of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 63:4755-4763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curtis, M. A., H. K. Kuramitsu, M. Lantz, L. Marcina, K. Nakayama, J. Potempa, E. C. Reynolds, and J. Aduse-Opoku. 1999. Molecular genetics and nomenclature of proteases of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Periodontal Res. 34:464-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuturi, M. C., R. Josien, D. Cantarovich, L. Bugeon, I. Anegon, S. Menoret, H. Smit, P. Douillard, and J. P. Soulillou. 1994. Decreased anti-donor major histocompatibility complex class I and increased class II alloantibody response in allograft tolerance in adult rats. Eur. J. Immunol. 24:1627-1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahlback, M., H. Bergstrand, R. Pauwels, and H. Bazin. 1983. The non-specific enhancement of allergy. III. Precipitation of bronchial anaphylactic reactivity in primed rats by injection of alum or B. pertussis vaccine: relation of response capacity to IgE and IgG2a antibody levels. Allergy 38:261-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis, W., P. T. Harrison, M. J. Hutchinson, and J. M. Allen. 1995. Two distinct regions of FC gamma RI initiate separate signalling pathways involved in endocytosis and phagocytosis. EMBO J. 14:432-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans, R. T., B. Klausen, H. T. Sojar, G. S. Bedi, C. Sfintescu, N. S. Ramamurthy, L. M. Golub, and R. J. Genco. 1992. Immunization with Porphyromonas (Bacteroides) gingivalis fimbriae protects against periodontal destruction. Infect. Immun. 60:2926-2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fanger, N. A., D. Voigtlaender, C. Liu, S. Swink, K. Wardwell, J. Fisher, R. F. Graziano, L. C. Pfefferkorn, and P. M. Guyre. 1997. Characterization of expression, cytokine regulation, and effector function of the high affinity IgG receptor Fc gamma RI (CD64) expressed on human blood dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 158:3090-3098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Genco, C. A., B. M. Odusanya, J. Potempa, J. Mikolajczyk-Pawlinska, and J. Travis. 1998. A peptide domain on gingipain R which confers immunity against Porphyromonas gingivalis infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 66:4108-4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibson, F. C., and C. A. Genco. 2001. Prevention of Porphyromonas gingivalis-induced oral bone loss following immunization with gingipain R1. Infect. Immun. 69:7959-7963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han, N., J. Whitlock, and A. Progulske-Fox. 1996. The hemagglutinin gene A (hagA) of Porphyromonas gingivalis 381 contains four large, contiguous, direct repeats. Infect. Immun. 64:4000-4007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holt, S. C., and T. E. Bramanti. 1991. Factors in virulence expression and their role in periodontal disease pathogenesis. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 2:177-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holt, S. C., J. Ebersole, J. Felton, M. Brunsvold, and K. S. Kornman. 1988. Implantation of Bacteroides gingivalis in nonhuman primates initiates progression of periodontitis. Science 239:55-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jefferis, R., J. Pound, J. Lund, and M. Goodall. 1994. Effector mechanisms activated by human IgG subclass antibodies: clinical and molecular aspects. Ann. Biol. Clin. 52:57-65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katz, J., K. P. Black, and S. M. Michalek. 1999. Host responses to recombinant hemagglutinin B of Porphyromonas gingivalis in an experimental rat model. Infect. Immun. 67:4352-4359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz, J., D. C. Ward, and S. M. Michalek. 1996. Effect of host responses on the pathogenicity of strains of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 5:309-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kesavalu, L., S. C. Holt, and J. L. Ebersole. 1997. Porphyromonas gingivalis virulence in a murine lesion model: effects of immune alterations. Microb. Pathog. 23:317-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klausen, B., R. T. Evans, N. S. Ramamurthy, L. M. Golub, C. Sfintescu, J. Y. Lee, G. Bedi, J. J. Zambon, and R. J. Genco. 1991. Periodontal bone level and gingival proteinase activity in gnotobiotic rats immunized with Bacteroides gingivalis. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 6:193-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klausen, B., H. P. Haugen, and N. Fiehn. 1989. Increased periodontal bone loss in temporarily B lymphocyte-deficient rats. J. Periodontal Res. 24:384-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laemmli, U. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamont, R. J., and H. F. Jenkinson. 1998. Life below the gum line: pathogenic mechanisms of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1244-1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lebman, D. A., and R. L. Coffman. 1994. Cytokines in the mucosal immune system, p. 243-250. In P. L. Ogra (ed.), Handbook of mucosal immunology. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 27.Lee, J. Y., H. T. Sojar, G. S. Bedi, and R. J. Genco. 1991. Porphyromonas (Bacteroides) gingivalis fimbrillin: size, amino-terminal sequence, and antigenic heterogeneity. Infect. Immun. 59:383-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maley, J., and I. S. Roberts. 1994. Characterisation of IS1126 from Porphyromonas gingivalis W83: a new member of the IS4 family of insertion sequence elements. Microbiol. Lett. 123:219-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKee, A. S., A. S. McDermid, R. Wait, A. Baskerville, and P. D. Marsh. 1988. Isolation of colonial variants of Bacteroides gingivalis W50 with a reduced virulence. J. Med. Microbiol. 27:59-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miklos, K., M. Tolnay, H. Bazin, and G. A. Medgyesi. 1993. Rat IgG subclasses mediating binding and phagocytosis of target cells by homologous macrophages. Mol. Immunol. 30:1273-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moss, R. B., M. A. Carmack, and S. Esrig. 1992. Deficiency of IgG4 in children: association of isolated IgG4 deficiency with recurrent respiratory tract infection. J. Pediatr. 120:16-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Brien-Simpson, N. M., C. L. Black, P. S. Bhogal, S. M. Cleal, N. Slakeski, T. J. Higgins, and, E. C. Reynolds. 2000. Serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgG subclass responses to the RgpA-Kgp proteinase-adhesin complex of Porphyromonas gingivalis in adult periodontitis. Infect. Immun. 68:2704-2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Brien-Simpson, N. M., R. A. Paolini, and E. C. Reynolds. 2000. RgpA-Kgp peptide-based immunogens provide protection against Porphyromonas gingivalis challenge in a murine lesion model. Infect. Immun. 68:4055-4063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okamoto, K., K. Nakayama, T. Kadowaki, N. Abe, D. B. Ratnayake, and K. Yamamoto. 1998. Involvement of a lysine-specific cysteine proteinase in hemoglobin absorption and heme accumulation by Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Biol. Chem. 273:21225-21231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oliver, R., L. Brown, and H. Loe. 1998. Periodontal diseases in the United States population. J. Periodontol. 69:269-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Persson, G. R., D. Engel, G. Whitney, R. Darveau, A. Weinberg, M. Brunsvold, and P. C. Page. 1994. Immunization against Porphyromonas gingivalis inhibits progression of experimental periodontitis in nonhuman primates. Infect. Immun. 62:1026-1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rangarajan, M., J. Aduse-Opoku, J. M. Slaney, A. Katherine, K. A. Young, and M. A. Curtis. 1997. The prpR1 and prpR2 arginine-specific protease genes of Porphyromonas gingivalis W50 produce five biochemically distinct enzymes. Mol. Microbiol. 23:955-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reynolds, E. C., and A. Del Rio. 1994. Effect of casein and whey protein solutions on caries experience of the rat. Arch. Oral Biol. 30:927-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reynolds, E. C., and N. M. O'Brien-Simpson. 2000. Cardiovascular disease and periodontal disease: microbial direct toxic effects on endothelial cells. Periodontology 21:24-31. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russell, M. W., D. A. Sibley, E. B. Nikolova, M. Tomana, and J. Mestecky. 1997. IgA antibody as a non-inflammatory regulator of immunity. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 25:466-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma, A., K. Honma, R. T. Evans, D. E. Hruby, and R. J. Genco. 2001. Oral immunization with recombinant Streptococcus gordonii expressing Porphyromonas gingivalis FimA domains. Infect. Immun. 69:2928-2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi, Y., D. B. Ratnayake, K. Okamoto, N. Abe, K. Yamamoto, and K. Nakayama. 1999. Genetic analyses of proteolysis, hemoglobin binding, and hemagglutination of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Construction of mutants with a combination of rgpA, rgpB, kgp, and hagA. J. Biol. Chem. 274:17955-17960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shibata, Y., M. Hayakawa, H. Takiguchi, T. Shiroza, and Y. Abiko. 1999. Determination and characterization of the hemagglutinin-associated short motifs found in Porphyromonas gingivalis multiple gene products. J. Biol. Chem. 274:5012-5020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Slakeski, N., P. S. Bhogal, N. M. O'Brien-Simpson, and E. C. Reynolds. 1998. Characterization of a second cell-associated Arg-specific cysteine proteinase of Porphyromonas gingivalis and identification of an adhesin binding motif involved in association of the PrtR-PrtK proteinases and adhesins into large complexes. Microbiolology 144:1583-1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Slakeski, N., S. M. Clean, P. S. Bhogal, and E. C. Reynolds. 1999. Characterization of a Porphyromonas gene prtK that encodes a lysine-specific cysteine proteinase and three sequence-related adhesins. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 14:92-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slakeski, N., S. M. Clean, and E. C. Reynolds. 1996. Characterization of a Porphyromonas gingivalis gene prtR that encodes an arginine-specific thiol proteinase and multiple adhesins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 224:605-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Slots, J. 1982. Host-parasite interactions in peridontal disease, p. 27-45. In R. J. Genco and S. E. Merganahagan (ed.), Importance of black-pigmented Bacteroides in human peridontal disease. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 48.Socransky, S. S., and A. D. Haffajee. 1991. Microbial mechanisms in the pathogenesis of destructive periodontal disease: a critical assessment. J. Periodontal Res. 26:1195-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Socransky, S. S., A. D. Haffajee, M. A. Cugini, C. Smith, and R. L. Kent, Jr. 1998. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J. Clin. Periodontol. 25:134-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sojar, H. T., N. Hamada, and R. J. Genco. 1997. Isolation and characterization of fimbriae from a sparsely fimbriated strain of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2318-2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song, E. S., K. Young, and D. W. Sears. 1990. Rat and human natural killers exhibit contrasting immunoglobulin G subclass specificities in antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity reflecting differences in their Fc receptors (Fc gamma R). J. Leukoc. Biol. 48:524-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stiles, B. G., A. R. Garza, R. G. Ulrich, and J. W. Boles. 2001. Mucosal vaccination with recombinantly attenuated staphylococcal enterotoxin B and protection in a murine model. Infect. Immun. 69:2031-2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sutterwala, F. S., G. J. Noel, P. Salgame, and D. M. Mosser. 1998. Reversal of proinflammatory responses by ligating the macrophage Fcg receptor. J. Exp. Med. 188:217-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suzuki, Y., F. Yoshimura, K. Takahashi, H. Tani, and T. Suzuki. 1988. Detection of fimbriae and fimbrial antigens on the oral anaerobe Bacteroides gingivalis by negative staining and serological methods. J. Gen. Microbiol. 134:2713-2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Travis, J., R. Pike, T. Imamura, and J. Potempa. 1997. Porphyromonas gingivalis proteinases as virulence factors in the development of periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 32:120-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Milligen, F. J., J. B. Cornelissen, I. M. Hendriks, C. P. Gaasenbeek, and B. A. Bokhout. 1998. Protection of Fasciola hepatica in the gut mucosa of immune rats is associated with infiltrates of eosinophils, IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies around the parasites. Parasite Immunol. 20:285-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wykes, M., A. Pombo, C. Jenkins, and G. G. MacPherson. 1998. Dendritic cells interact directly with naive B lymphocytes to transfer antigen and initiate class switching in a primary T-dependent response. J. Immunol. 161:1313-1319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamada, M., M. Nakazawa, and N. Arizono. 1993. IgE and IgG2a antibody responses are induced by different antigen groups of the nematode Nippostrongylus brasiliensis in rats. Immunology 78:298-302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yonezawa, H., K. Ishihara, and K. Okuda. 2001. Arg-gingipain A DNA vaccine induces protective immunity against infection by Porphyromonas gingivalis in a murine model. Infect. Immun. 69:2858-2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zoda, T., T. M. Yeh, and K. A. Krolick. 1991. Clonotypic analysis of anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies from experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis-sensitive Lewis rats and experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis-resistant Wistar Furth rats. J. Immunol. 146:663-670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]