Abstract

We investigated the ability of two overlapping fragments of staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB), which encompass the whole toxin, to induce protection and also examined if passive transfer of chicken anti-SEB antibodies raised against the holotoxin could protect rhesus monkeys against aerosolized SEB. Although both fragments of SEB were highly immunogenic, the fragments failed to protect mice whether they were injected separately or injected together. Passive transfer of antibody generated in chickens (immunoglobulin Y [IgY]) against the whole toxin suppressed cytokine responses and was protective in mice. All rhesus monkeys treated with the IgY specific for SEB up to 4 h after challenge survived lethal SEB aerosol exposure. These findings suggest that large fragments of SEB may not be ideal for productive vaccination, but passive transfer of SEB-specific antibodies protects nonhuman primates against lethal aerosol challenge. Thus, antibodies raised in chickens against the holotoxin may have potential therapeutic value within a therapeutic window of opportunity after SEB encounter.

The staphylococcal enterotoxins (SEs) are a family of bacterial superantigens (BSAgs) produced by Staphylococcus aureus. These protein toxins bind to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules and, with less affinity, to the T-cell antigen receptors without MHC molecules, resulting in intense stimulation of the immune system that triggers acute pathological effects (8, 11, 20). BSAgs are associated with several serious diseases, including food poisoning, bacterial arthritis, and lethal toxic shock syndrome (7, 12). In addition, viral infections may predispose patients to toxic shock syndrome caused by BSAg-associated secondary streptococcal or staphylococcal infection (4, 16). The main component of the intoxication process depends on the ability of BSAgs to activate a large number of T cells, causing a massive release of inflammatory cytokines (7, 20).

Because SEs can cause severe pathologies and are considered potential biowarfare agents, there is considerable need to develop vaccines and therapeutic approaches capable of eliminating their toxicity. Previously, we showed that genetically altered staphylococcal enterotoxin A (SEA) and SEB inactivated by a site-directed mutagenesis strategy and lacking superantigenic effects were highly immunogenic in mice and rhesus monkeys (2, 20, 21). These recombinant vaccines elicited neutralizing antibodies that were detected in in vitro surrogate assays and protected the vaccinees against wild-type (WT) SEA and SEB. The experiments reported here were initiated to find fragments of SEB that could be used for vaccine purposes and to examine the suitability of passive immunotherapy with anti-SEB antibody developed in chickens (immunoglobulin Y [IgY]) against lethal effects of SEB in mice and rhesus monkeys. The data presented here highlight a useful therapeutic maneuver that could be employed to reduce or eliminate BSAg-mediated toxic shock syndrome and possibly other associated disorders.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Pathogen-free BALB/c (H-2d), 10- to 12-week-old mice were obtained from Harlan Sprague-Dawley (Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center, Frederick, Md.). The mice were maintained under pathogen-free conditions and fed laboratory chow and water ad libitum. Rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) weighing 4 to 8 kg were maintained in nonhuman primate cages in a facility fully accredited by the American Association of Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. The monkeys had full access to filtered tap water ad libitum and were fed approved commercially available food and fresh fruits. All animal manipulations were performed after administration of a dose of Telezole anesthetic (3 to 6 mg/kg given intramuscularly).

Research was conducted in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and other federal statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals and adhered to principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The facility where the research was conducted is fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International.

BSAgs and vaccines.

Engineered recombinant SEB vaccine containing three site mutations (SEB L45R/Y89A/Y94A) was prepared in our laboratory as described elsewhere (21). Briefly, the WT SEB gene was isolated from S. aureus, and site-specific mutations were created. The final construct had three mutations, SEB L45R, Y89A, and Y94A, and is referred to below as SEBv. The vaccine was purified by ion-exchange chromatography after bacterial lysis. A recombinant SEB N-terminal fragment containing the first 99 amino acid residues of SEB (SEB1-99) and a C-terminal fragment containing amino acid residues 66 to 243 (SEB66-243) were made under contract by Ophidian Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Madison, Wis.). Both fragments were expressed containing a polyhistidine tag and were purified with an Ni resin column. The SEBv and N- and C-terminal fragments were more than 95% pure, as determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. WT toxins, SEBv, and the fragments contained less than 10 endotoxin units/200 μl, as determined by the Limulus lysate assay. Toxins were purchased from Toxin Technology (Sarasota, Fla.). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli O55:B5 was obtained from Difco Laboratories (Detroit, Mich.).

Vaccination protocol and passive protection.

Two weeks prior to vaccination or immunotherapy, mice and rhesus monkeys were bled, and their serum antibody titers against SEs and toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 were determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to be <1:50 (2). In the vaccination protocol, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 10 μg of vaccine in 100 μl of Ribi adjuvant (Ribi Immunochem Research, Hamilton, Mont.) or with adjuvant alone and boosted at 2 and 4 weeks in the manner used for the primary injection. Ten days after the last injection, blood was collected from the tail vein of each mouse, and serum was separated. Mice were challenged 2 weeks after the second boost with 2 μg of SEB per mouse (approximately 10 50% lethal doses [LD50]) and LPS (75 μg per mouse), as described elsewhere (2, 3). The challenge controls were adjuvant-injected or naïve mice were injected with both toxin and LPS (all of the mice died) or with one of the agents (no death was observed).

For passive transfer studies, chicken anti-SEB antibodies (IgY) raised against WT SEB, SEB1-99, SEB66-243, or a combination of the two fragments were made under contract by Ophidian Pharmaceuticals, Inc., as previously described (17). Briefly, laying leghorn hens were given intramuscular injections of 250 to 500 μg of SEB or the fragments in Freund's adjuvant and boosted at 2, 4, and 6 weeks. Eggs were collected 2 weeks after the last vaccination, and the anti-SEB IgY was isolated by immunoaffinity chromatography against SEB attached to a solid surface (10). The antibodies were dialyzed extensively against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the amount of protein was measured. For mice, SEB-specific antibody (200 μg) or PBS was incubated (1 h, 37°C) with 5 μg (approximately 25 LD50) of WT SEB, and mice were injected with the mixture. A potentiating dose of LPS was given to the mice, and lethality was scored, as described above. For rhesus monkeys, prior to initiation of the experiments the animals were anesthetized with 3 to 6 mg of Telazole per kg, and they remained anesthetized during antibody injection and SEB exposure. Rhesus monkeys were injected with 10 mg of chicken antibodies per kg in sterile saline before SEB exposure or 4 h after the animals were exposed to approximately 5 LD50 of aerosolized SEB, as previously described (19).

Serum antibody titers.

Serum antibody titers were determined as described elsewhere (2). The mean duplicate absorbance of each treatment group was obtained, and data are presented below as the inverse of the highest dilution that produced an absorbance reading twice that of the negative control wells (antigen or serum was omitted from the negative control wells).

T-lymphocyte assay.

To demonstrate SEB-specific T-cell inhibition by purified chicken anti-SEB antibodies, pooled mouse sera obtained from vaccinated or control mice were incubated (1 h, 37°C) with various doses of SEB (10 or 100 ng/ml). Each mixture was added to donor mononuclear cells obtained from unvaccinated mouse spleens, and the amount of [3H]thymidine incorporation (in counts per minute) was measured with a liquid scintillation counter (2, 10).

Detection of cytokines.

Mice were bled 5 h after SEB injection, and serum-borne cytokine levels were determined. Interleukin-1α (IL-1α) levels were determined by ELISA (Genzyme Corporation). Actinomycin D (2 μg/ml)-sensitized L-929 cells were used as cytolytic targets to measure serum tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) activity. Serum gamma interferon (IFN-γ) activity was determined by MHC class II induction in the monocyte-macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 with complement-mediated cytotoxicity as an end point. Standard curves were constructed with mouse recombinant TNF-α (3.125 to 200 U/ml) and recombinant IFN-γ (1.56 to 100 U/ml). Cytotoxicity was determined colorimetrically by using the redox dye Alamar Blue (Alamar, Inc., Sacramento, Calif.) as an indicator of viability. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical methods.

For T-cell proliferation assays, mean values and standard deviations were compared by using Student's t test. Final lethality was statistically scored by using Fisher's exact tests.

RESULTS

Vaccine efficacy of SEB fragments.

We examined two fragments of SEB that encompass the whole protein and overlap by 33 amino acid residues (Table 1). As shown in Table 1, the SEB fragments (SEB1-99 and SEB66-243) and SEBv were not lethal in mice in the presence of a potentiating dose of LPS. In contrast, all mice that received WT SEB and a potentiating dose of LPS died. Vaccination with SEBv, the SEB fragments, and WT SEB was highly immunogenic in mice and elicited serum anti-SEB titers that exceeded 105.

TABLE 1.

Vaccination with the SEB fragments elicited no neutralizing antibodies

| Agent | Acute toxicity (no. live/no. dead)a | Efficacy

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Titerb | Inhibition of T-cell proliferation (%)c | % Survivald | ||

| SEBv | 10/0 | >105 | 97 | 100 |

| SEB1-99 | 10/0 | >105 | 3e | 0e |

| SEB66-243 | 10/0 | >105 | 0e | 0e |

| Both fragments | 10/0 | >105 | 2e | 0e |

| WT SEB | 0/10 | >105 | 95 | 100 |

Naïve mice were injected with 10 μg of SEBv, the SEB fragments, or WT SEB and a potentiating dose of LPS. Lethality was recorded 4 days after the challenge dose was administered.

Mice were vaccinated intraperitoneally and boosted at 2 and 4 weeks. Ten days after the last vaccination, the mice were bled and serum titers against SEB were determined. The data are expressed as the reciprocal serum dilution resulting in an optical density twice that of the negative controls (ELISA wells containing either no toxin or no primary antibody).

SEB (10 ng/ml) and sera that were obtained 2 weeks after the last vaccination were preincubated before they were added to splenic mononuclear cells. The data are expressed as the percentage of SEB stimulation, where inhibition = 100 − [(experimental counts per minute for sera from vaccinated mice)/(counts per minute for SEB in the presence of sera from naïve mice) × 100]. The standard errors of the means for triplicate wells were <10% for the calculated values.

Mice were challenged with 2 μg of SEB per mouse (approximately 10 LD50) and a potentiating dose of LPS (75 μg) 2 weeks after the final boost, and lethality was recorded 4 days after the challenge dose was administered.

The P value compared to SEBv was <0.001.

Previously, it was shown that suppression of BSAg-induced T-cell activation was a highly predictive biomarker and surrogate end point for immunity in subjects that were vaccinated with the SEB vaccine (2, 21). Therefore, we analyzed the neutralizing ability of the vaccinees' sera in a T-cell proliferation assay. We incubated WT SEB with pooled sera obtained from vaccinated mice or PBS, added the mixture to naïve donor responder T cells, and measured SEB-induced T-cell proliferation (Table 1). Three injections with SEBv and three injections with WT SEB toxin produced substantial amounts of neutralizing antibodies and inhibited SEB-induced T-cell proliferation by 97 and 95%, respectively, and all of the mice survived a lethal SEB challenge. Although three vaccinations with either SEB fragment injected separately or with the two fragments injected together produced high ELISA titers, the antibodies were incapable of suppressing T-cell responses to SEB, and they failed to protect in vivo.

Passive transfer of antibody mimics vaccination studies.

Immunopurified chicken antibodies (IgY) against WT SEB suppressed the ability of SEB to induce T-cell stimulation in vitro when mouse T cells were used (Table 2). The IgY preparation protected mice from lethal SEB challenge (Table 2). However, purified IgY antibodies that were raised against the SEB fragments were not protective in an in vitro surrogate T-cell assay and failed to protect mice against SEB challenge. These data suggest that antibodies raised in chickens against the holotoxin may have potential therapeutic value.

TABLE 2.

Passive transfer of IgY raised against WT SEB, but not antibodies raised against the SEB fragments, protects against SEB-induced toxicity

| Treatment | % Inhibitiona | % Survivalb |

|---|---|---|

| IgY SEB1-99 | 0c | 0d |

| IgY SEB66-243 | 0c | 10d |

| Both fragments (IgY) | 0c | 10d |

| IgY WT SEB | 90 | 90 |

Immunopurified IgY and SEB (100 ng/ml) were incubated for 1 h and then added to splenic mononuclear cells. The data are expressed as the percentage of SEB stimulation, where inhibition = 100 − [(experimental counts per minute for anti-SEB or anti-SEB fragment IgY)/(medium control counts per minute) × 100].

Affinity-purified IgY and 5 μg (approximately 25 LD50) of SEB were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Mice were given the mixture, and then they were injected with a potentiating dose of LPS (75 μg). Lethality was recorded 4 days after the challenge dose was administered.

The P value for all experimental cultures compared to cultures that were treated with IgY raised against WT SEB was <0.001.

P < 0.01 compared with IgY raised against WT SEB.

Inflammatory cytokine responses in vaccinated mice.

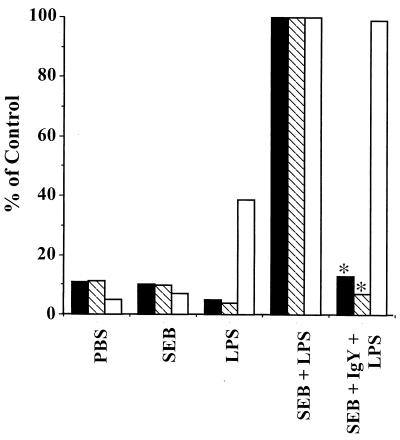

Because inflammatory cytokines play a central role in the lethal toxicity triggered by SEs, we next compared the profiles of inflammatory cytokine (IL-1α, TNF-α, and IFN-γ) responses in mice given lethal doses of SEB mixed with chicken-derived neutralizing anti-SEB IgY or buffer and a potentiating dose of LPS. The mice were bled 5 h after injection of SEB (5 μg/mouse, approximately 25 LD50), and the levels in serum of IL-1α, TNF-α, and IFN-γ were measured. Cytokine levels in mice that were treated with PBS and challenged with SEB and a potentiating dose of LPS were used as the 100% positive control (Fig. 1). Mice that received LPS or SEB alone had little or no detectable blood-borne TNF-α and IFN-γ. Unlike the profiles of other cytokines, the IL-1α levels in mice injected with LPS alone increased to 40% of the control level. Compared with the levels in mice injected with both SEB and LPS, the levels of serum TNF-α and IFN-γ were not elevated in animals that were given SEB in combination with anti-SEB IgY and LPS. While the IL-1α level was substantially increased in mice lethally challenged with SEB and LPS, protective treatment with chicken anti-SEB antibodies did not alter the profile of this cytokine. The lack of suppression of this cytokine in passively vaccinated mice suggests that some residual SEB, not bound by the antibodies, may have been available to induce the observed increase in IL-α levels. Indeed, injecting submicrogram levels of SEB with a potentiating dose of LPS resulted in a substantial increase in the IL-1α level (unpublished observation).

FIG. 1.

Passive transfer of chicken-derived anti-SEB antibody to mice inhibits SEB-induced TNF-α and IFN-γ release. SEB (5 μg/mouse) was incubated for 1 h at 37°C with anti-SEB IgY or PBS. Mice were given the mixture, and then they were injected with a potentiating dose of LPS (75 μg). Serum cytokine levels were determined as described in Materials and Methods. The results are expressed as percentages of the positive control (mice treated with PBS and challenged with SEB and a potentiating dose of LPS). The standard errors of the means for duplicate wells were <10% for calculated values. An asterisk indicates that the P value compared with the positive control (mice treated with PBS and challenged with SEB and a potentiating dose of LPS) was <0.001. Solid bars, IFN-γ; cross-hatched bars, TNF-α; open bars, IL-1α.

Passive transfer of antibodies against SEB to nonhuman primates.

Previously, we showed that administration of immunopurified anti-SEB antibodies obtained from naturally exposed humans completely protected mice up to 4 h after systemic toxin administration (10). However, humans and other primates are more sensitive to BSAgs than most nonprimate species, and because of this level of sensitivity nonhuman primate animal models are probably the most relevant models for examining therapeutics and vaccines against BSAgs. Therefore, we investigated the efficacy of passive transfer of chicken anti-SEB antibodies in rhesus monkeys. So that our results would have a practical benefit, we evaluated the effect of anti-SEB IgY against aerosolized WT SEB challenge, because this is the most likely route of delivery of this toxin as a biological weapon. Rhesus monkeys were given anti-SEB antibody 20 min before the challenge and 4 h after exposure by the aerosol route to 5 LD50 of SEB (19). Passively vaccinated rhesus monkeys were treated with molar ratios of antibody to toxin of 21:1 to 37:1. The amounts of antibody were selected based on a preliminary experiment with mice that showed that a 20:1 ratio of antibody to SEB was needed for the optimal neutralizing effects (data not shown). All four rhesus monkeys that were given anti-SEB antibody at the time of challenge survived (Table 3). More interestingly, when the antibody treatment was delayed for 4 h, all four of the passively immunized rhesus monkeys survived the challenge, while monkeys that received no antibody rescue dose died. Collectively, these results suggest that the chicken antibody produced against WT SEB is efficacious in mice and rhesus monkeys and that there is a therapeutic window of opportunity after SEB encounter.

TABLE 3.

Passive treatment of SEB-intoxicated rhesus monkeys with anti-SEB IgY antibody

| Monkey | Treatmenta | Time of treatment | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anti-SEB IgY | Before challengeb | Live |

| 2 | Anti-SEB IgY | Before challenge | Live |

| 3 | Anti-SEB IgY | Before challenge | Live |

| 4 | Anti-SEB IgY | Before challenge | Live |

| 5 | Anti-SEB IgY | 4 h after challenge | Live |

| 6 | Anti-SEB IgY | 4 h after challenge | Live |

| 7 | Anti-SEB IgY | 4 h after challenge | Live |

| 8 | Anti-SEB IgY | 4 h after challenge | Live |

| 9 | Buffer | Before challenge | Dead |

| 10 | Buffer | 4 h after challenge | Dead |

Rhesus monkeys were given chicken anti-SEB (IgY) antibody or buffer only 20 min before or 4 h after the SEB challenge.

Rhesus monkeys were challenged by the aerosol route with 5 LD50 of SEB.

DISCUSSION

Previously, we showed that BSAgs can be inactivated by rational site-directed mutagenesis and that the genetically altered constructs can be used for vaccine purposes (2, 21). Here, we examined if a large fragment(s) could be used for efficacious vaccination and to determine the efficacy of antibodies elicited in chickens against SEB in mice and nonhuman primates. Initially, we adopted a reductionistic approach and examined two fragments that encompassed the SEB toxin and overlapped by 33 amino acid residues. Although, as expected, both fragments were highly immunogenic in mice and produced the same ELISA titers against SEB as the genetically engineered vaccine candidate produced, neither fragment produced neutralizing antibody, and vaccination with these fragments did not protect against the WT BSAg.

Peptides corresponding to different portions of BSAgs have been used with limited success to modulate immune responses (9, 13, 14). Recently, carboxyl-terminal peptides, including sequences highly conserved among BSAgs, have also been identified which provided extensive cross-protection against challenge with a number of BSAgs in rabbit and sensitized-mouse models (1, 22). It is interesting that these small peptides showed protective activity, while our large SEB fragment (SEB66-243) was not protective. One possible explanation is that antigen processing, which is required for efficient antigen presentation, typically involves denaturation and proteolytic cleavage by acid proteases before encounter with and binding of MHC class II molecules in peptide-loading compartments (5, 6, 15). This harsh environment may have destroyed the protective epitopes within SEB66-243. In contrast to SEB66-243, synthetic peptides of SEB may be able to bind MHC class II molecules without further processing in antigen-presenting cells. The peptides that were used by Visvanathan et al. and Arad et al., therefore, can be considered already processed antigens which mimic physiologically generated peptides (1, 22). In agreement with our explanation, Shimonkevitz et al. showed that exogenously added synthetic peptides were presented by cell surface MHC class II molecules of antigen-presenting cells without preprocessing (18). Understanding the mechanism of SEB antigen presentation to T cells is critical in the development of vaccines against these protein toxins. Therefore, studies are under way to examine the vaccine efficacy of other longer or shorter fragments of SEB. Other ongoing experiments will address secondary structural changes using circular dichroism, and the stability of fragments will be tested by differential scanning calorimetry.

In support of a protective antibody role, it was recently shown that there was a clear correlation between antibody titers and inhibition of T-cell responses to BSAgs, and the potentiated mouse model was used to demonstrate that high-titer pooled human sera can protect mice against SEB challenge (10). Here, we extended the previous observations and showed that chicken antibody raised against whole SEB molecules substantially reduced the amounts of blood-borne inflammatory cytokines in a murine model and protected them from lethal effects of SEB. Unlike human and nonhuman primate lymphocyte responses to BSAgs, murine cells respond only to high concentrations of these toxins in vitro (11). Consequently, mice are significantly less susceptible to the toxic effects of BSAgs, and wild-type mice are not an ideal animal model for pathogenesis of BSAgs or for testing therapeutic and vaccination approaches to deal with staphylococcal and streptococcal infections. To obtain additional data, we tested purified anti-SEB IgY antibodies in a rhesus monkey model of SEB-induced lethal shock after an aerosol challenge. Using this model, we passively transferred the antibodies to SEB-naïve monkeys and measured their survival after lethal doses of SEB delivered by the aerosol route. We showed that 100% pre- and postexposure protection was provided by immunopurified anti-SEB antibody raised in chickens in this relevant rhesus monkey model. Using the chicken antibody product may have several advantages, such as a reduced anaphylaxis reaction, delayed-type hypersensitivity, and substantial cost savings. Altogether, our observations suggest that anti-SEB IgY may offer substantial protection both as a prophylactic agent and as a therapeutic agent against lethal aerosolized doses of SEB.

Editor: E. I. Tuomanen

REFERENCES

- 1.Arad, G., R. Levy, D. Hillman, and R. Kaempfer. 2000. Superantigen antagonist protects against lethal shock and defines a new domain for T-cell activation. Nat. Med. 6:414-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bavari, S., B. Dyas, and R. G. Ulrich. 1996. Superantigen vaccines: a comparative study of genetically attenuated receptor-binding mutants of staphylococcal enterotoxin A. J. Infect. Dis. 174:338-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bavari, S., R. G. Ulrich, and R. D. LeClaire. 1999. Cross-reactive antibodies prevent the lethal effects of Staphylococcus aureus superantigens. J. Infect. Dis. 180:1365-1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brook, M. G., and B. A. Bannister. 1991. Staphylococcal enterotoxins in scarlet fever complicating chickenpox. Postgrad. Med. J. 67:1013-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cresswell, P. 1994. Antigen presentation. Getting peptides into MHC class II molecules. Curr. Biol. 4:541-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cresswell, P. 1994. Assembly, transport, and function of MHC class II molecules. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 12:259-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraser, J., V. Arcus, P. Kong, E. Baker, and T. Proft. 2000. Superantigens—powerful modifiers of the immune system. Mol. Med. Today 6:125-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraser, J. D. 1989. High-affinity binding of staphylococcal enterotoxins A and B to HLA-DR. Nature 339:221-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griggs, N. D., C. H. Pontzer, M. A. Jarpe, and H. M. Johnson. 1992. Mapping of multiple binding domains of the superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin A for HLA. J. Immunol. 148:2516-2521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LeClaire, R. D., and S. Bavari. 2001. Human antibodies to bacterial superantigens and their ability to inhibit T-cell activation and lethality. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:460-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marrack, P., and J. Kappler. 1990. The staphylococcal enterotoxins and their relatives. Science 248:1066.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michie, C. A., and J. Cohen. 1998. The clinical significance of T-cell superantigens. Trends Microbiol. 6:61-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pontzer, C. H., N. D. Griggs, and H. M. Johnson. 1993. Agonist properties of a microbial superantigen peptide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 193:1191-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pontzer, C. H., M. J. Irwin, N. R. Gascoigne, and H. M. Johnson. 1992. T-cell antigen receptor binding sites for the microbial superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:7727-7731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sant, A. J., and J. Miller. 1994. MHC class II antigen processing: biology of invariant chain. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 6:57-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarawar, S. R., M. A. Blackman, and P. C. Doherty. 1994. Superantigen shock in mice with an inapparent viral infection. J. Infect. Dis. 170:1189-1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schade, R., P. Henklein, A. Hlinak, J. de Vente, and H. Steinbusch. 1996. Specificity of chicken (IgY) versus rabbit (IgG) antibodies raised against cholecystokinin octapeptide (CCK-8). Altern. Tierexp. 13:80-85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimonkevitz, R., S. Colon, J. W. Kappler, P. Marrack, and H. M. Grey. 1984. Antigen recognition by H-2-restricted T cells. II. A tryptic ovalbumin peptide that substitutes for processed antigen. J. Immunol. 133:2067-2074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tseng, J., J. L. Komisar, R. N. Trout, R. E. Hunt, J. Y. Chen, A. J. Johnson, L. Pitt, and D. L. Ruble. 1995. Humoral immunity to aerosolized staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB), a superantigen, in monkeys vaccinated with SEB toxoid-containing microspheres. Infect. Immun. 63:2880-2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ulrich, R. G., S. Bavari, and M. A. Olson. 1995. Bacterial superantigens in human disease: structure, function and diversity. Trends Microbiol. 3:463-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ulrich, R. G., M. A. Olson, and S. Bavari. 1998. Development of engineered vaccines effective against structurally related bacterial superantigens. Vaccine 16:1857-1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Visvanathan, K., A. Charles, J. Bannan, P. Pugach, K. Kashfi, and J. B. Zabriskie. 2001. Inhibition of bacterial superantigens by peptides and antibodies. Infect. Immun. 69:875-884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]