Abstract

Novel homologous DsbA-like disulfide bond formation (Dsb) proteins of Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Ehrlichia canis were identified which restored DsbA activity in complemented Escherichia coli dsbA mutants. Recombinant Ehrlichia Dsb (eDsb) proteins were recognized by sera from E. canis-infected dogs but not from E. chaffeensis-infected patients. The eDsb proteins were observed primarily in the periplasm of E. chaffeensis and E. canis.

Members of the genus Ehrlichia exhibit typical gram-negative cell wall structure; however, limited ultrastructural studies suggest that peptidoglycan may be absent. Bacterial outer membranes lacking peptidoglycan may be more dependent on covalent and noncovalent associations of outer membrane proteins. Disulfide bond linkages between cell envelope proteins of organisms in the genus Ehrlichia have not been determined, but two ultrastructural forms of Ehrlichia chaffeensis, termed reticulate and dense-cored cells, correspond to ultrastructurally similar reticulate and elementary body forms observed in chlamydiae (13), and an increase in disulfide cross-linked proteins has been noted in elementary bodies of Chlamydia spp. (3). Intramolecular covalent disulfide bonds between major surface proteins of the related rickettsial pathogen Anaplasma marginale have also been described and suggest that disulfide linkages are important in ehrlichial outer membrane structure (16).

Thio-disulfide oxidoreductases have been characterized in the cell envelope of several bacteria (1, 5, 10) and are likely involved in determining the three-dimensional structure of folded outer membrane proteins by catalyzing intra- and intermolecular disulfide bond formation. Disulfide oxidoreductases in Escherichia coli include thioredoxin and disufide bond formation (Dsb) proteins A, B, C, D, and E (9, 14, 15). Some overlap in function occurs among these Dsb proteins, as overexpression of DsbC can alleviate the defects in DsbA mutants (8). We describe in this report functional immunoreactive homologous periplasmic thio-disulfide oxidoreductases, or Dsb proteins, of E. chaffeensis and Ehrlichia canis. The role of ehrlichial Dsb proteins in outer membrane supramolecular structure, pathogenesis, and protective immunity remains to be determined.

The E. canis dsb gene was identified by immunologic screening of a Lambda Zap II E. canis genomic library as described previously (7). Screening of the E. canis genomic library identified an immunoreactive 2.4-kb clone with one complete and a second incomplete open reading frame (ORF) 42 bp downstream on the complementary strand. The second ORF was disrupted by a HinP1/HpaII cutting site used to construct the library, but it encoded a protein of at least 309 amino acids (ORF-309). A search of nucleic acid and protein databases did not identify any significant homologous sequences to ORF-309. The E. chaffeensis dsb gene was amplified by PCR using forward primer p27nc42 (5′-GAG ATT TCT ACT ATT GAC TTC-3′), targeting the upstream noncoding region, and reverse primer ECa27-700r (5′-CAG CTG CAC CAC CGA TAA ATG TA-3′), obtained as sequences complementary to the E. canis dsb sequence. This primer pair amplified a region beginning upstream of the start codon through nucleotide 700 of the 738-bp ORF. The undetermined carboxy terminus (38 bp) and the primer ECa27-700r annealing region (23 bp) of the E. chaffeensis dsb gene were obtained with primer ECf27-475 (5′-TTC TAC CAT GCT GCA CTA AAC C-3′), which amplified in the 3′ direction, using a genome walking kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) as previously described (17). The E. chaffeensis and E. canis dsb genes were both 738-bp encoding proteins of 246 amino acids with predicted molecular masses of 27.7 and 27.5 kDa, respectively. The nucleic acid homology between the Ehrlichia dsb genes was 84%, but there was no homology with other database sequences.

Ehrlichia Dsb (eDsb) amino acid sequences were analyzed by the method of Neilsen et al. (11) for signal sequence recognition by using SignalP (version 1.1) at the Center for Biological Sequence Analysis (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/). Homologous domain architecture was determined using the domain architecture retrieval tool (DART) with reverse position-specific BLAST of the conserved domain database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/lexington/lexington.cgi?cmd=rps). Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences, protein hydrophilicity, and surface probability were determined with LASERGENE software (version 5.0; DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, Wis.), using the Kyte-Doolittle and Emini algorithms. A conserved amino acid domain architecture found in the thioredoxin superfamily was identified in the eDsb proteins, and it was most similar to E. coli DsbA according to DART. A conserved cysteine active site was identified in the eDsb proteins that was identical to the active site of E. coli DsbC. The eDsb proteins are 87% homologous, contain identical predicted hydrophobic N-terminal signal peptide sequences consisting of 15 amino acids (MLRILFLLSLVILVA), and share some homology with Coxiella burnetii Com1 (31%) (4). The eDsb proteins, C. burnetii Com1, and periplasmic E. coli DsbA exhibited similar hydrophilicity and surface probability. In contrast, cytoplasmic membrane protein DsbB of E. coli had very few hydrophilic regions but had hydrophobic regions indicative of membrane-spanning proteins.

The entire E. chaffeensis dsb ORF was amplified by PCR with primers ECh27f (5′-ATG CTA AGG ATT TTA TTT TTA TTA-3′) and ECh27r (5′-TCC TTG CTC ATC TAT TTT ACT TC-3′) and cloned directly into the pCR T7/CT TOPO TA expression vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.), which is designed to produce proteins with a native N terminus and a carboxy-terminal polyhistidine region for purification. The resulting construct was designated pECf-dsb. E. chaffeensis and E. canis dsb genes without native N-terminus signal peptide-encoding regions (E. chaffeensis, −75 bp; E. canis, −73 bp) were amplified by PCR using forward primers ECh27-75 (5′-ATG AGC AAA TCT GGT AAA ACT AT-3′) and ECa27-73 (ATG TCT AAT AAA TCT GGT AAG C-3′) and reverse primers ECh27r and ECa27r (5′-TTT CTG CAT ATC TAT TTT AC-3′), cloned into the same expression vector, and designated pECf-Dsb-sp and pECa-Dsb-sp. The recombinant eDsb proteins were purified under denaturing conditions as described previously (7), and the expressed recombinant protein was used for stimulating antibody production and Western blotting experiments. The purified recombinant eDsb proteins' migration on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) coincided with their predicted molecular masses (Fig. 1A). Both recombinant eDsbs reacted with rabbit anti-E. chaffeensis recombinant Dsb, demonstrating the existence of a cross-reactive eDsb epitope (Fig. 1B). Polyclonal antisera produced against the E. chaffeensis recombinant Dsb protein also reacted with native proteins in the whole-cell lysates of E. chaffeensis (26 kDa) and E. canis (25 kDa), but not uninfected DH82 lysate (Fig. 1C). Normal rabbit serum did not react with the ehrlichia or DH82 cell lysate (not shown). Sera from dogs with canine monocytic ehrlichiosis (CME) reacted strongly with the recombinant E. canis Dsb and exhibited weaker reactivity with the recombinant E. chaffeensis Dsb (Fig. 2). Immune sera from human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME) patients that contained antibodies to E. chaffeensis detected by an immunofluorescent antibody test did not react with the E. chaffeensis recombinant Dsb (Fig. 2).

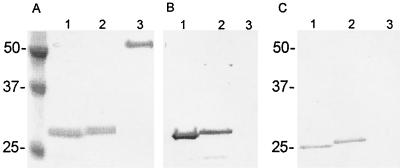

FIG. 1.

(A) Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE of partial recombinant eDsb proteins (−24 N-terminal amino acids) of E. canis (lane 1) and E. chaffeensis (lane 2) and control protein (lane 3) expressed in E. coli. The C-terminal polyhistidine fusion tag accounts for approximately 3 kDa of the molecular mass. (B) Corresponding Western blot with anti-E. chaffeensis recombinant Dsb antibody. (C) Immunoblot of SDS-PAGE-separated E. canis (lane 1), E. chaffeensis (lane 2), and DH82 (lane 3) cell lysates reacted with anti-E. chaffeensis Dsb antibody.

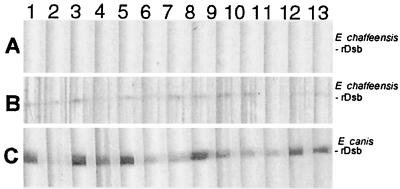

FIG. 2.

Western immunoblot of E. chaffeensis recombinant Dsb (rDsb) with HME patient sera (A, lanes 1 to 13) and CME dog sera (B, lanes 1 to 13) and E. canis rDsb with CME dog sera (C, lanes 1 to 13).

The eDsb protein function was determined using E. coli strains JCB502 and JCB572 (JCB502 dsbA::kan1), kindly provided by J. Bardwell (University of Michigan), in complementation experiments as reference and mutant strains, respectively (1). E. coli dsbA mutant strain JCM572 carries a kanamycin insertion in the dsbA gene and is immotile due to a defect in flagellar assembly related to a disulfide bond in the flagellar P-ring protein (2). Expression constructs pECf-Dsb and pECf-Dsb-sp, containing the complete and signal peptide-deficient E. chaffeensis dsb constructs and an expression plasmid control, were electroporated (2.5 kV, 25 μF, 200 Ω) into E. coli strain JCM572 and selected on Luria-Bertani (LB) plates with 100 μg of ampicillin. Mutants were screened for motility on soft agar LB plates (0.22% agar) for 18 h at 37°C. Alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity was determined by culturing cells in minimal medium, and activity was calculated using the formula [(optical density at 420 nm with substrate) − (optical density at 420 nm without substrate)] × 103, as described previously (5). E. chaffeensis dsb gene constructs of the complete ORF, pECf-Dsb, and excluding the N-terminal signal peptide region, pECf-Dsb-sp, were electroporated into E. coli strain JCM572. A plasmid control expressing the lacZ gene was used as a negative control in the E. coli dsbA mutants. Complementation of JCB572 with the pECf-Dsb gene construct resulted in the restoration of motility in the normally immotile E. coli dsbA mutant that was similar to that observed in the reference strain, JCM502. Motility was not restored in JCB572 using the pECf-Dsb-sp gene construct, which lacked 25 amino acids on the N terminus of the protein, including the predicted 15-amino-acid signal peptide, or with the lacZ plasmid control. AP is a disulfide-bonded periplasmic enzyme, and disulfide bonds must be formed for its proper folding and activity. Decreased AP activity in dsbA mutants has been reported (6). To confirm the disulfide bond formation activity demonstrated in the motility experiments, we compared AP activity in the wild type with that in the E. chaffeensis dsb-complemented E. coli dsbA mutants. The reference strain JCB502 and JCB572(pECf-Dsb) exhibited similar AP activities (65 and 63 U), JCB572(pECf-Dsb-sp) had approximately 30% lower AP activity (47 U), and the plasmid control, JCB572(pLacZ) had very low AP activity (5 U).

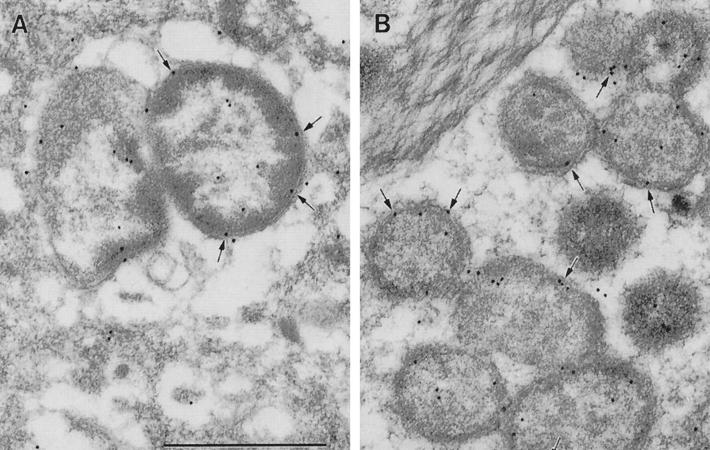

Localization of eDsb proteins in fixed LR White-embedded ultrathin sections of DH82 cells infected with E. chaffeensis and E. canis was performed as described previously (12). Ultrathin sections were treated with blocking buffer (0.1% bovine serum albumin and 0.01 M glycine in Tris-buffered saline, [TBS]), incubated with rabbit anti-E. chaffeensis recombinant Dsb polyclonal antibody diluted 1:100 in diluting buffer (1% bovine serum albumin in TBS), and washed in blocking buffer, followed by incubation with goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (H+L) labeled with 15-nm colloidal gold particles (AuroProbe EM GAR G15, RPN422; Amersham Life Science, Arlington Heights, Ill.) diluted 1:20 in diluting buffer. Ultrathin sections of E. chaffeensis and E. canis in infected DH82 cells were incubated with rabbit anti-E. chaffeensis recombinant Dsb. eDsb proteins were identified primarily in the cytoplasmic membrane-periplasmic region, with most label appearing to be in the periplasmic space of both E. chaffeensis and E. canis. Cytoplasmic localization was observed, which is consistent with production and transport of eDsb from the cytoplasm to the periplasm, and occasional surface labeling was observed (Fig. 3). No difference was observed in the amount of eDsb in dense-cored and reticulate cells.

FIG. 3.

Postembedding immunogold staining of E. chaffeensis and E. canis with anti-E. chaffeensis recombinant Dsb rabbit antiserum. Bar, 1 μm. (A) E. chaffeensis (Arkansas strain) in DH82 cells; (B) E. canis (Oklahoma strain) in DH82 cells.

Little is known about the mechanism of disulfide bond formation and the role of inter- and intramolecular disulfide bonds in the overall cell envelope structure in Ehrlichia. This is the first report of a thio-disulfide oxidoreductase in Ehrlichia, and it provides evidence that disulfide bond formation may occur, perhaps playing an important role in the ehrlichial life cycle and pathogenesis. Previous studies with the related agent A. marginale demonstrated the importance of intra- and intermolecular disulfide bonds in the supramolecular structure of the cell envelope (16). Disulfide bonds in chlamydiae are involved in the development of ultrastructural forms of the organism (3), which are similar in appearance to the Ehrlichia reticulate and dense-cored forms (12). E. coli Dsb proteins provide some information regarding the possible role of ehrlichial Dsb proteins. It is not clear at this point what role the eDsb proteins have in pathogenesis or immunity, but studies to determine the role of disulfide bonds in cell envelope structure and cell ultrastructure will provide additional insights into the role of eDsb proteins in the ehrlichial life cycle.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers. The GenBank nucleotide sequence accession numbers for the E. chaffeensis and E. canis dsb genes are AF403710 and AF403711, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank James Bardwell for providing the E. coli strains JCB502 and JCB572 necessary for conducting the complementation experiments and Violet Han for expert electron microscopy assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Clayton Foundation for Research and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI31431 to D.H.W.).

Editor: J. T. Barbieri

REFERENCES

- 1.Bardwell, J. C., K. McGovern, and J. Beckwith. 1991. Identification of a protein required for disulfide bond formation in vivo. Cell 67:581-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dailey, F. E., and H. C. Berg. 1993. Mutants in disulfide bond formation that disrupt flagellar assembly in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:1043-1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatch, T. P., I. Allan, and J. H. Pearce. 1984. Structural and polypeptide differences between envelopes of infective and reproductive life cycle forms of Chlamydia spp. J. Bacteriol. 157:13-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hendrix, L. R., L. P. Mallavia, and J. E. Samuel. 1993. Cloning and sequencing of Coxiella burnetii outer membrane protein gene com1. Infect. Immun. 61:470-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishihara, T., H. Tomita, Y. Hasegawa, N. Tsukagoshi, H. Yamagata, and S. Udaka. 1995. Cloning and characterization of the gene for a protein thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase in Bacillus brevis. J. Bacteriol. 177:745-749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamitani, S., Y. Akiyama, and K. Ito. 1992. Identification and characterization of an Escherichia coli gene required for the formation of correctly folded alkaline phosphatase, a periplasmic enzyme. EMBO J. 11:57-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McBride, J. W., R. E. Corstvet, E. B. Breitschwerdt, and D. H. Walker. 2001. Immunodiagnosis of Ehrlichia canis infection with recombinant proteins. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:315-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Missiakas, D., C. Georgopoulos, and S. Raina. 1994. The Escherichia coli dsbC (xprA) gene encodes a periplasmic protein involved in disulfide bond formation. EMBO J. 13:2013-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Missiakas, D., and S. Raina. 1997. Protein folding in the bacterial periplasm. J. Bacteriol. 179:2465-2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ng, T. C., J. F. Kwik, and R. J. Maier. 1997. Cloning and expression of the gene for a protein disulfide oxidoreductase from Azotobacter vinelandii: complementation of an Escherichia coli dsbA mutant strain. Gene 188:109-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen, H., J. Engelbrecht, S. Brunak, and G. von Heijne. 1997. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 10:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Popov, V. L., S. M. Chen, H. M. Feng, and D. H. Walker. 1995. Ultrastructural variation of cultured Ehrlichia chaffeensis. J. Med. Microbiol. 43:411-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Popov, V. L., V. C. Han, S. M. Chen, J. S. Dumler, H. M. Feng, T. G. Andreadis, R. B. Tesh, and D. H. Walker. 1998. Ultrastructural differentiation of the genogroups in the genus Ehrlichia. J. Med. Microbiol. 47:235-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raina, S., and D. Missiakas. 1997. Making and breaking disulfide bonds. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 51:179-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell, M., and P. Model. 1986. The role of thioredoxin in filamentous phage assembly. Construction, isolation, and characterization of mutant thioredoxins. J. Biol. Chem. 261:14997-15005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vidotto, M. C., T. C. McGuire, T. F. McElwain, G. H. Palmer, and D. P. Knowles, Jr. 1994. Intermolecular relationships of major surface proteins of Anaplasma marginale. Infect. Immun. 62:2940-2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu, X. J., J. W. McBride, X. F. Zhang, and D. H. Walker. 2000. Characterization of the complete transcriptionally active Ehrlichia chaffeensis 28 kDa outer membrane protein multigene family. Gene 248:59-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]