Geophagia is defined as deliberate consumption of earth, soil, or clay1. From different viewpoints it has been regarded as a psychiatric disease, a culturally sanctioned practice or a sequel to poverty and famine. Prompted by a remarkable case in our own practice2 we became increasingly aware of geophagia in contemporary urban South Africa. In view of the high prevalence of geophagia there and in many other regions of the world1, we hypothesized that ancient medical texts would also contain reports of the disorder. To our surprise, geophagia was indeed reported by many authors ranging from Roman physicians to 18th century explorers. Here we present, together with a brief description of the disorder, some of the most remarkable examples.

GEOPHAGIA

From a psychiatric point of view, geophagia has been classed as a form of pica3—a term that comes from the Latin for magpie, a bird with indiscriminate eating habits. In its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, the American Psychiatric Association defines pica as persistent eating of non-nutritive substances that is inappropriate to developmental level, occurs outside culturally sanctioned practice and, if observed during the course of another mental disorder, is sufficiently severe to warrant independent attention4. Geophagia denotes the habit of eating earth, soil or clay and is not uncommon in southern parts of the United States5 as well as urban Africa. Fine red clay is often preferred (Figure 1). In particular, geophagia is observed during pregnancy6 or as a feature of iron-deficiency anaemia7. Where poverty and famine are implicated1, earth may serve as an appetite suppressant and filler; similarly, geophagia has been observed in anorexia nervosa. However, geophagia is often observed in the absence of hunger, and environmental and cultural contexts of the habit have been emphasized8. Finally, geophagia is encountered in people with learning disability, particularly in the context of long-term institutionalization; in this regard, geophagia and other forms of pica are associated with a high rate of complications9 and substantial morbidity10 and mortality11. Geophagia has also been reported to serve specific purposes. For example, young women in urban South Africa believe that earth-eating will give them a lighter colour (making them supposedly more attractive) and soften their skin. There is reason to believe that geophagia often goes unrecognized by doctors because patients are reluctant to volunteer the history. Indeed, stigma plays a role, and concealment of the aberrant eating behaviour is an important issue. The diagnosis commonly emerges when a patient is accidentally discovered during a ‘binge’ of geophagia12. Abdominal radiography2 can be of great help in the occasional patient who fervently denies the habit. Complications of geophagia are rare but closely linked to the amount of ingested material. They include parasitic infestation, electrolyte disturbances and intestinal obstruction. Perforation and peritonitis are rare but the associated mortality is very high2.

Figure 1.

A sample of clay obtained from vendor in urban Johannesburg, South Africa

ANTIQUITY

Despite limited insight into anatomy and physiology, Greek and Roman medical textbooks reveal astute descriptions of medical disorders and striking diagnostic acumen. The textbook compiled by Hippocrates of Kos (460-377 BC) provides a masterly example. Hippocrates, who marks the transition from a magical view of health and disease to one of belief in causation, must be credited with the first description of geophagia:

‘If a pregnant woman feels the desire to eat earth or charcoal and then eats them, the child will show signs of these things’13.

For centuries, Hippocrates' textbook was a cornerstone of medical practice, so we can assume that Greek and Roman physicians were familiar with geophagia. But even today the reason for geophagia in pregnancy remains elusive6. A famous Roman medical textbook, De Medicina, was compiled by A Cornelius Celsus during the reign of Emperor Tiberius (14-37 AD). His second book contains a passage that deals with the use of skin colour as a diagnostic sign:

‘People whose colour is bad when they are not jaundiced are either sufferers from pains in the head or earth eaters’14.

Even this early report points to a link between geophagia and anaemia. It is still unclear, however, whether anaemia prompts geophagia (to compensate for iron deficiency) or whether geophagia is the cause of anaemia7. Taken together, the reports provided by Hippocrates and Celsus suggest that earth-eating was not uncommon in ancient times. Pliny (Gaius Plinius Secundus, 23-79 AD), a universal scientific writer, supports this assumption. He describes the popularity of alica, a porridge-like cereal that contained red clay:

‘Used as a drug it has a soothing effect... as a remedy for ulcers in the humid part of the body such as the mouth or anus. Used in an enema it arrests diarrhoea, and taken through the mouth... it checks menstruation’15.

Aetius of Amida, now the Turkish city of Djabakir, compiled an obstetric textbook during the 6th century that provides evidence from the Byzantine era. A physician to Emperor Justinian in Constantinople, Aetius states:

‘Approximately during the second month of pregnancy, a disorder appears that has been called Pica, a name derived from a living bird, the magpie... Women then desire different objects... some prefer spicy things, others salty dishes and again others earth, egg shells or ashes’16.

THE MIDDLE AGES

Fewer reports of geophagia are available from this period, partly because of the scarcity of new medical works in general. Instead, Roman, Greek and Arab textbooks were used at the time. The Persian Ibn Sina (980-1037 AD), also known as Avicenna, compiled one of the most widely used medical textbooks and made detailed mention of geophagia. To cure geophagia in young boys Avicenna recommended imprisonment12, but more gentle treatment was advocated during pregnancy17. In medieval Europe both gynaecology and obstetrics were largely performed by midwives, and few documents survive. An exception is the remarkable textbook written by Trotula of Salerno. A midwife in the 11th century, she dealt with geophagia as a common but treatable problem in pre-delivery care:

‘But if she should seek to have potter's earth or chalk or coals, let beans cooked with sugar be given to her’18.

GEOPHAGIA IN THE 16TH AND 17TH CENTURIES

Many reports of geophagia are available from this period, and the term pica was first mentioned in the context of a surgical work19. Geophagia was often observed as a symptom of another disease, chlorosis. The ‘green disease’, also known as febris alba, mainly affected pubescent girls and spread widely through Europe during the 16th century20. In France, Libault described geophagia in maidens suffering from chlorosis in 158221. The exact nature of chlorosis remains controversial but anaemia must have been a salient feature. In view of the well-described association of anaemia and geophagia7, Libault's observations are not surprising.

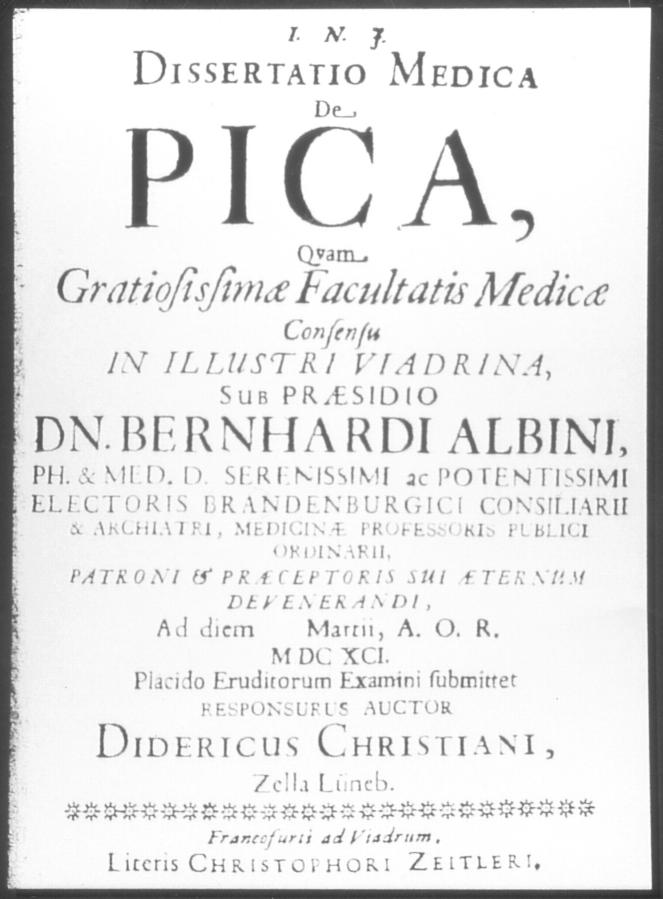

More information can be gathered from medical dissertations about pica. In this regard, some twenty thesis papers from the 16th and 17th centuries can be found in the British Library alone. Among reports of other forms of pica, they describe a remarkable spectrum of geophagia. We must be cautious, however, in taking them at face value. Indeed, it has been speculated that some of these reports originally stem from mocking descriptions in songs and jokes of wandering minstrels22. Among the authors of these theses, Boetius was the first to advocate iron treatment23. Ledelius, in turn, made attempts to explain the pathogenesis of the disorder: he believed that pieces of leftover food rotted in the stomach and subsequently spoiled the sense of taste and caused craving for all sorts of substances24. Veryser in Utrecht was the first to regard pica as a mental disorder: ‘In this disorder, two sites are affected, namely stomach and mind’25. Many of these authors, again, observed geophagia during pregnancy. Christian provided a remarkable description of various forms of geophagia and vividly described the disorder: ‘A girl ate earth and similar things just as they were bread’ (Figure 2)26.

Figure 2.

Title page of doctoral thesis on pica

But geophagia was not only observed in young women suffering from chlorosis. An astonishing report of geophagia as a sequel to famine during the 17th century, by the superintendent of Coswig in Saxony, dates from 1617:

‘So people finally started baking this earth and [...] the hill containing this white earth was undermined and collapsed killing five’27.

Finally, geophagia was also mentioned by scientists travelling abroad during the 17th century. Dr John Covel, travelling the Levant, reported in great detail on the use of terra sigillata, the sacred earth, to facilitate childbirth and alleviate disorders of menstruation28.

ANTHROPOLOGISTS, COLONIAL PHYSICIANS AND EXPLORERS

Geophagia remained common in Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries; in particular, it was still observed in young girls with chlorosis20. Even more reports, however, were compiled by anthropologists, colonial physicians and explorers. One of these authors who came to wide attention was von Humboldt, who noted geophagical customs in natives of South America:

‘This area is populated by the Otomacs, a forgotten tribe which shows the most peculiar behaviour. The Otomacs eat earth, that is they wolf it down in quite considerable amounts’29.

Humboldt described geophagia in great detail and asserted that hunger could in part explain this behaviour. In particular, he observed that dried earth was piled up in heaps to serve as a store during periods of famine. It is noteworthy that members of the Otomac tribe were selective, preferring a brand of fine red clay that seems similar to that consumed in South Africa (see Figure 1). In Africa, Livingstone later described safura, a disease of earth-eating among slaves in Zanzibar. Livingstone refuted poverty as a possible explanation after observing that wealthy people were also affected. The course of the disorder was described as invariably fatal30. Similar reports from colonial physicians are discussed in great detail elsewhere22. Here, the disorder was often viewed as a matter of great concern among plantation owners, in that slaves who were addicted to geophagia became progressively more lethargic and debilitated until they eventually died. Plantation owners went so far as to have face masks fitted to prevent the slaves from eating earth31,32 (see Figure 3). Similar habits developed among slaves in southern parts of North America, where geophagia was known as cachexia Africana33; the disorder is still seen in Georgia and Louisiana. Finally, reports are available from India34 and the remainder of Asia20.

Figure 3.

Mouth-locks worn by slaves in Brazil to prevent geophagia

CONCLUSION

All the concepts of geophagia—as psychiatric disorder, culturally sanctioned practice or sequel to famine—fall short of a satisfying explanation. The causation is certainly multifactorial; and clearly the practice of earth-eating has existed since the first medical texts were written. The descriptions do not allow simple categorization as a psychiatric disease. Finally, geophagia is not confined to a particular cultural environment and is observed in the absence of hunger. Might it be an atavistic mode of behaviour, formerly invaluable when minerals and trace elements were scarce? Its re-emergence might then be triggered by events such as famine, cultural change or psychiatric disease. A beautiful description of the latter can be found in Gabriel García Màrquez' novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude, where he describes geophagia in a woman who is madly in love:

‘Rebecca got up in the middle of the night and ate handfuls of earth in the garden with a suicidal drive, weeping with pain and fury, chewing tender earthworms and chipping her teeth on snail shells’35.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to staff at the British Library, London, for excellent service, and to Dr Wolfgang Woywodt for help with German sources.

References

- 1.Hawass NED, Alnozha MM, Kolawole T. Adult geophagia—report of three cases with review of the literature. Trop Geogr Med 1987;39: 191-5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woywodt A, Kiss A. Perforation of the sigmoid colon due to geophagia. Arch Surg 1999;134: 88-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLoughlin IJ. The picas. Br J Hosp Med 1987;37: 286-90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994

- 5.Edwards CH, Johnson AA, Knight EM, et al. Pica in an urban environment. J Nutr 1994;124: 954S-962S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Rourke DE, Quinn JG, Nicholson JO, Gibson HH. Geophagia during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1967;29: 581-4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sayers G, Lipschitz DA, Sayers M, Seftel HC, Bothwell TH, Charlton RW. Relationship between pica and iron nutrition in Johannesburg black adults. S Afr Med J 1974;68: 1655-60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vermeer DE, Frate DA. Geophagia in rural Mississippi: environmental and cultural contexts and nutritional implications. Am J Clin Nutr 1979;32: 2129-35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Decker CJ. Pica in the mentally handicapped: a 15-year surgical perspective. Can J Surg 1993;36: 551-4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ilhan Y, Cifter C, Dogru O, Akkus MA. Sigmoid colon perforation due to geophagia. Acta Chir Belg 1999;99: 130-1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLoughlin IJ. Pica as a cause of death in three mentally handicapped men. Br J Psychiatry 1988;152; 842-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosselle HA. Association of laundry starch and clay ingestion with anemia in New York City. Arch Intern Med 1970;125: 57-61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hippocrates. Oevres Complètes d'Hippocrate, Vol. 8, Little E, transl. Paris: Baillière, 1839: 487 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Celsus. De Medicina. Spencer WG, transl. Cambridge/Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1971: 116-17.

- 15.Pliny. Natural History, Vol. 9, Rackham H, transl. London: Heinemann, 1972: 285 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wegscheider M. Geburtshülfe und Gynäkologie bei Aëtius von Amida. Berlin: Julius Springer Verlag, 1901: 11-12

- 17.Kipel KF. Picca. In: The Cambridge World History of Human Disease. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993: 927

- 18.Mason-Hohl E. The Diseases of Women by Trotula of Salerno. Hollywood/Los Angeles: Ward Ritchie Press, 1940: 21

- 19.Gale T. An Excellent Treatise of Wounds made with Gonneshot. London: R Hall, 1563

- 20.Parry-Jones B, Parry-Jones WL. Pica: symptom or eating disorder? A historical assessment. Br J Psychiatry 1992;160: 341-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Líebault J. Trois Libres Appartenant aux Infirmitez et Maladies des Femmes. Paris, 1609

- 22.Cooper M. Pica. Springfield, Illinois: CL Thomas, 1957

- 23.Boetius MH. De Pica. Leipzig, 1638

- 24.Ledelius J. Dissertatio inauguralis de Pica. Jena: Christoph Krebs, 1668

- 25.Veryser P. Disputatio medica inauguralis de malacia seu pica. Utrecht: Franziskus Halma, 1694

- 26.Christian D. Dissertatio medica de pica. Frankfurt/Oder: Christoph Zeitler, 1691: 11

- 27.Ströse K. Mitteilung über das Diatomeenlager bei Klieken in Anhalt. In: Suhle H, ed. IX Jahresbericht des Friedrichs-Realgymnasiums und der Vorschule des Fridericianum für das Schuljahr 1890-1891. Dessau: L. Reiter Herzogl. Hofbuchdrucker, 1891

- 28.Bent JF. Early Voyages and Travels in the Levant. London: Hakluyt Society, 1903, 282

- 29.Von Humboldt A. Vom Orinokko zum Amazonas. Wiesbaden: FA Brockhaus, 1985, 341

- 30.Livingstone D. Last Journals. London: John Murray, 1874: 83

- 31.Anell B, Lagercrantz S. Geophagical Customs. Uppsala: Almquist and Wiksell, 1958: 63

- 32.Debret JB. Voyage pittoresque et historique au Brésil, ou, Séjour d'un artiste français au Brésil, depuis 1816 jusqu'en 1831 inclusivement. Paris: Firmin-Didot Fréres, 1834

- 33.Mustacchi P. Cesare Bressa (1785-1836) on dirt eating in Louisiana. A critical analysis of his unpublished manuscript De la Dissolution Scorbutique. JAMA 1971;218: 229-32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thurston E. Ethnographic Notes in Southern India. Madras: Government Press, 1906: 552

- 35.García Màrquez G. Cien Años de Soledad. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1982, 120