Abstract

Most strains of Shigella flexneri 2a and enteroaggregative Escherichia coli carry a highly conserved chromosomal locus which encodes a 109-kDa secreted mucinase (called Pic) and, on the opposite strand in overlapping fashion, an oligomeric enterotoxin called ShET1, encoded by the setA and setB genes. Here, we characterize the genetic regulation of these overlapping genes. Our data suggest that pic and the setBA loci are transcribed as complementary 4-kb mRNA species. The major pic promoter is maximally activated at 37°C in exponential growth phase. Our data suggest that the setB gene is transcribed from a promoter which lies more than 1.5 kb upstream of the setB structural gene; setA may be transcribed via readthrough of the setB transcript and possibly by its own promoter. The long leader of the setB gene provides a strong silencing effect on setB transcription. The signals which provide relief from setB silencing are not clear, but significant induction is observed in a continuous anaerobic culture of human fecal bacteria, suggesting that some complex characteristics of the human intestine act to lift repression of setB expression. Our studies provide the first insights into the mechanisms affecting expression of this unusual virulence locus.

Shigella flexneri and enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC) are enteric pathogens implicated as agents of diarrheal disease throughout the world. Whereas multiple virulence factors and mechanisms have been elucidated for these organisms, most of the work has focused on plasmid-borne virulence genes. However, several recent studies suggest that genes on the chromosomes of these pathogens are likely to play important roles in pathogenesis (1, 4, 9, 12, 13, 22, 34).

We and others have shown that most S. flexneri 2a and EAEC strains share a chromosomal locus, designated pic/set, which encodes at least two putative virulence factors (1, 4, 9). In S. flexneri, pic/set is encoded on a pathogenicity island called SHI-1 (1); the sequence of the island encoding pic/set in EAEC has not been reported. pic/set encodes a high-molecular-weight mucinase (Pic), which is a serine protease secreted by the autotransporter mechanism (12). Pic degrades intestinal mucin and may play a role in mucosal colonization by both EAEC and S. flexneri 2a strains. Encoded on the opposite strand but completely within the pic gene is an oligomeric enterotoxin called Shigella enterotoxin 1 (ShET1), which is thought to comprise a single 20-kDa catalytic A subunit (encoded by the setA gene) and five 7-kDa B subunits (encoded by the setB gene) (9). The ShET1 mode of action has not been defined, but it does not appear to act via the traditional mediators of toxin-induced intestinal secretion, such as cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP (10).

S. flexneri and EAEC have different pathogenetic strategies. S. flexneri is a large-bowel pathogen which causes invasive and inflammatory colitis (for a review, see reference 11). Many shigellosis patients experience a watery prodromal phase, which may be a manifestation of early small-bowel involvement and to which ShET1 may contribute. In contrast, EAEC are thought to be distal small-bowel and/or colonic pathogens which typically cause watery diarrhea without evidence of invasion or frank inflammation (26). Nevertheless, recent data suggest that EAEC may induce mild inflammatory enteritis (31).

We approached the characterization of the pic/set locus with the aim of understanding when in the pathogenic sequence these loci are expressed and how this expression is controlled. Clarification of these events will provide further understanding of EAEC and S. flexneri pathogenesis and may also shed light on signals recognized by enteric pathogens in general. Our data suggest that both loci are expressed in the intestinal lumen; moreover, our results suggest a novel mechanism of ShET1 regulation and the existence of pathogen-specific regulators of pic and setBA. We also report for the first time the use of a continuous anaerobic culture to study expression of virulence genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. All E. coli strains were grown aerobically at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium unless otherwise stated. Antibiotics were added at the following concentrations when appropriate: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 50 μg/ml, and tetracycline, 50 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| 042 | Wild-type EAEC prototype strain | 25 |

| E. coli TE2680 | K-12 F−/λ− IN(rrnD-rrnE)1 Δ(lac)X74 rpsL galK2 recD1903::Tn10d-Tet trpDC700::putPA1303::[Kans-Camr-lac] | 8 |

| E. coli One Shot | K-12 F− mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 deoR araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Strr) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen Corp. |

| E. coli M182 | E. coli used as background for hns and stpA mutants; DE(codB-lac1)3, galK16 galE15 LAM− e14−relA1 rpsL150 (STRr) spoT1 | M. Belfort |

| E. coli M182 hns | Kanamycin resistance gene replacing native hns gene of E. coli M182 | M. Belfort |

| E. coli stpA | Tetracycline resistance gene replacing native stpA gene of E. coli M182 | M. Belfort |

| 042fis | 042 carrying TnphoA insertion affecting fis expression | 29 |

| S. flexneri 2457T | Wild-type S. flexneri 2a | 6 |

| P3/2 | TE2680 φ 197-bp fragment with the Ppic3 promoter::lacZ | This study |

| P15/2 | TE2680 φ 1,110-bp fragment with the Ppic1,2,3 promoter::lacZ | This study |

| P16/2 | TE2680 φ 280-bp fragment with the Ppic2,3 promoter::lacZ | This study |

| S8/1 | TE2680 φ 400-bp fragment with the setA promoter::lacZ | This study |

| S23/1 | TE2680 φ 2,755-bp fragment with the setA and setB promoter::lacZ | This study |

| S23/19 | TE2680 φ 2,360-bp fragment with the setB promoter and the silencer region::lacZ | This study |

| S25/26 | TE2680 φ 260-bp fragment with the setB promoter::lacZ | This study |

| S25/32 | TE2680 φ 310-bp fragment with the setB promoter and 50 bp of the silencer region::lacZ | This study |

| S40/19 | TE2680 φ 463-bp fragment with the setB promoter and 69 bp of the silencer region::lacZ | This study |

| S41/19 | TE2680 φ 394-bp fragment with the setB promoter and the deleted silencer region::lacZ | This study |

| S42/19 | TE2680 φ 559-bp fragment with the setB promoter and 165 bp of the silencer region::lacZ | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRS551 | lacZ reporter gene fusion vector | Simons |

| pP3/2 | 197-bp fragment with the Ppic3 promoter in pRS551 | This study |

| pP4/2 | 158-bp fragment without promoter in pRS551 | This study |

| pP15/2 | 1,110-bp fragment with the Ppic1,2,3 promoter in pRS551 | This study |

| pP16/2 | 280-bp fragment with the Ppic2,3 promoter in pRS551 | This study |

| pP16/20 | 82-bp fragment with the Ppic2 promoter in pRS551 | This study |

| pS8/1 | 400-bp fragment with the setA promoter in pRS551 | This study |

| pS12/1 | 211-bp fragment without promoter in pRS551 | This study |

| pS23/1 | 2,755-bp fragment with the setA and setB promoter and the silencer region in pRS551 | This study |

| pS23/19 | 2,360-bp fragment with the setB promoter and the silencer region in pRS551 | This study |

| pS25/26 | 260-bp fragment with the setB promoter in pRS551 | This study |

| pS25/32 | 310-bp fragment with the setB promoter and 50 bp of the silencer region in pRS551 | This study |

| pS40/19 | 463-bp fragment with the setB promoter and 69 bp of the silencer region in pRS551 | This study |

| pS41/19 | 394-bp fragment with the setB promoter and the deleted silencer region in pRS551 | This study |

| pS42/19 | 559-bp fragment with the setB promoter and 165 bp of the silencer region in pRS551 | This study |

| pP37/19 | pP16/2 with the 1,562-bp silencer region in the silencing orientation in pRS551 | This study |

| pP37/19inv | pP16/2 with the 1,562-bp silencer region in the inverted orientation in pRS551 | This study |

| pS37/19 | pS25/26 with the 1,562-bp silencer region in the silencing orientation in pRS551 | This study |

| pS37/19inv | pS25/26 with the 1,562-bp silencer region in the inverted orientation in pRS551 | This study |

| pPic1 | 5.7-kbp chromosomal fragment of EAEC 042 in pACYC184 | 12 |

| pΔpicΩ | pPic1 with deleted Ppic1,2,3 promoters and the Ω fragment cloned into EcoRI restriction site | This study |

| pΔset | pPic1 with deleted setA and setB promoters | This study |

Molecular cloning and sequencing procedures.

Plasmid DNA purification, restriction, ligation, transformation, and agarose gel electrophoresis were performed by standard methods (28). DNA sequence analysis was performed at the University of Maryland Department of Microbiology & Immunology Biopolymer Facility on an Applied Biosystems model 373A sequencer; template DNA was purified by using minicolumns from Amersham-Pharmacia-Biotech (Piscataway, N.J.).

lacZ fusion analysis.

To monitor transcriptional activities, defined fragments from the pic/set locus were amplified by PCR using primers carrying EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites. Fragments were directionally cloned into compatible sites in the promoterless lacZ reporter vector pRS551 (30). Clones are listed in Table 1, and primers are listed in Table 2. Cloned fragments were confirmed by plasmid isolation and restriction, PCR, and DNA sequencing. β-Galactosidase activity, expressed in Miller units, was measured as described previously (20).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Application | Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Stranda | 5′ endb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fusion constructions | Pic2RBamHI | GGATATGGATCCGTAACACAGACAGATTGCTG | − | 1131 |

| Pic3FEcoRI | TATCATGAATTCCTTCAGCTATTTTACTTTTAT | + | 934 | |

| Pic4FEcoRI | TGTAAAGAATTCGGAGAATCCATAATGAATAA | + | 973 | |

| Pic15FEcoRI | CATCATGAATTCCGGACGCTTACGAACTGACG | + | 21 | |

| Pic16FEcoRI | CTCCAGGAATTCCGGGGCGGTTCAGTTCACAA | + | 851 | |

| Pic20RBamHI | AAATAGGGATCCAAGCTAATGATAACCCGACGTT | − | 933 | |

| Shet1RBamHI | GACCGGGGATCCGGATGTCGCCATTCCACAGG | + | 2867 | |

| Shet8FEcoRI | CAGCGTGAATTCCCCTTCATACTGGCTCCTGT | − | 3267 | |

| Shet12FEcoRI | GTCAGCGAATTCCAGCGACAGTGTTTTCATTG | − | 3078 | |

| Shet19RBamHI | GGAGCCGGATCCAAGGGAATATTACGCTGAAC | + | 3262 | |

| Shet23FEcoRI | GAAAGCGAATTCCGCCATGTGCTTGGCGTCAT | − | 5622 | |

| Shet25FEcoRI | AAACAGGAATTCGCCAGTTGGCAAAACTAGTT | − | 5218 | |

| Shet26RBamHI | GATAAAGGATCCAAAGGACAGCCGGATGCTGT | + | 4958 | |

| Shet32RBamHI | CTGCTGGGATCCGGAGAGACCGTACTGCGTGA | + | 4908 | |

| Shet37FBamHI | TTACCAGGATCCGTCTTGCCCAGTTCAACCCC | − | 4838 | |

| Shet40FBamHI | ACCGGCGGATCCATGCCCGTCGCTGAAAAGAC | − | 3465 | |

| Shet41FBamHI | CAGTGAGGATCCGGCAAAAGCACCCGGGGCTG | − | 3396 | |

| Shet42FBamHI | GGTCAGGGATCCTCCGTCCGTCAGATATACAG | − | 3561 | |

| RT-PCR | Shet10F | GCCCTGTCACTTCCCAGTGT | − | 3170 |

| Shet13R | CGTAACGCCTCGCTGAACAG | + | 3102 | |

| Shet17F | GCAGGGTTGGGGTCACCCGA | − | 4138 | |

| Shet20FRT | CGCATATTGTCCTTTATCTG | − | 5018 | |

| Shet21FRT | GAAAGGCTGCCTTCCGGCAG | − | 5138 | |

| Shet22RRT | TAAGGCCGGCACCCGGGTGA | + | 4088 | |

| Shet24FRT | CGATACAAGCGTAGCAACGC | − | 1338 | |

| Shet25RRT | TATTGCCCCGTCACCGGGGG | + | 1008 | |

| Shet26RRT | ATGGGGGGACTGGCGCAAGC | + | 548 | |

| Shet28RRT | CCGGTGAAAACCTGGTATTC | + | 2038 | |

| Shet33FRT | GAATACCAGGTTTTCACCGG | − | 2058 | |

| Shet34RRT | GCGTTGCTACGCTTGTATCG | + | 1318 | |

| Shet35RRT | CTCTAATCCCGGGCAAACTT | + | 1688 | |

| Shet36FRT | AAGTTTGCCCGGGATTAGAG | − | 1708 | |

| Promoter deletions | INVPCR1 | TTTTCCTTTTGCGGCCGCCGAGTT | − | 500 |

| AGAGTTTTTTCCAGTATCGATTTT | ||||

| INVPCR2 | AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCATGGAG | + | 971 | |

| AATCCATAATGAATAAAGTTTATTCTC | ||||

| INVPCR3 | TTTTCCTTTTGCGGCCGCGCGAG | + | 5218 | |

| CCTGTTTAAGATTCTGTGTAAATG | ||||

| INVPCR4 | AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCTCTC | − | 4958 | |

| CTTTTATCCGTTTCTCCCCGGAC | ||||

| INVPCR5 | TTTTCCTTTTGCGGCCGCAGCCAG | + | 3252 | |

| TATGAAGGGAATATTACGCTGAAC | ||||

| INVPCR6 | AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCCATA | − | 2868 | |

| TTCCCGGTCAGCTGACCATGAAAGAT | ||||

| Real-time RT-PCR | RealF | TGTACCTGGTGCCAATGATA | + | 1215 |

| RealRI | CCGATATCCTCCGTTATGCT | − | 1380 | |

| RealRII | CGATATACTGAGGCGATACAA | − | 1351 | |

| SetAReal | CCCTGATATTCCAGGGACAT | + | 2962 | |

| SetARealF | ATGGAAGTCAGCGTCTTTCA | − | 3096 | |

| 8/1RaceII | GACAGTGGCACCCTGATATT | + | 2952 | |

| Shet9F | GGTACCTTCCTCCGGAATGA | − | 3225 | |

| SetBReal | CTGAACAGTGACATTAAGTC | + | 3114 | |

| Tet1R | TAAGAGCCGCGAGCGATCCT | —c | —c | |

| Tet2R | GAGCGATCCTTGAAGCTGTC | —c | —c | |

| Tet3F | TGGATGGCCTTCCCCATTAT | —c | —c | |

| Real control F | CTGGATATACCACCGTTGATATA | —d | —d | |

| Real control I | GGGTGAACACTATCCCATAT | —d | —d | |

| Real control II | TCAGGCGGGCAAGAATGTGA | —d | —d |

pic, setA, and setBA promoter regions were integrated into the chromosome of the E. coli K-12 strain TE2680 in a single copy as described previously (8). Briefly, the pRS551 plasmid carries a Kanr gene from Tn903 placed upstream of the E. coli lac operon, separated from lac by a transcriptional terminator. Strain TE2680 contains a region homologous to pRS551, comprising a Kanr gene (which has been inactivated by the insertion of a linker into the HindIII site) and a downstream segment consisting of the lac operon; between these two segments is a Camr fragment. TE2680 also bears a recD::Tn10d-Tet insertion to allow efficient recombination of linearized plasmid DNA. Transformation of 1 μg of linear DNA (cut with XhoI) and subsequent recombination yield Kanr Cams recombinants which represent replacement of the TE2680 lacZ gene with the chimeric pRS551 derivative (8). Transformants were screened for kanamycin resistance and chloramphenicol sensitivity; integration was verified by PCR prior to β-galactosidase assays.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR techniques.

Bacterial strains were grown to exponential phase, and whole-cell RNA was isolated using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase to eliminate contaminating DNA. cDNA was synthesized using sequence-specific primers (Table 2) and the Superscript enzyme from Gibco-BRL (Gaithersburg, Md.) for 10 min at 55°C. PCR was performed using standard procedures with Taq DNA polymerase (BRL). Controls for all reactions included samples without reverse transcriptase (negative control) and the relevant purified plasmid DNA (positive control).

The abundance of mRNA transcripts for pic and set genes was determined by real-time quantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR. RNA extracted as above was tested for DNA contamination by 40 cycles of standard PCR with the same primers used in the RT-PCR amplification. Single-step RT-PCR was performed with the Superscript enzyme in the presence of SYBR Green I dye (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany), followed by PCR performed according to the manufacturer's instructions using AmpliTaq Gold polymerase (Roche). Fluorescence was detected with the GeneAmp 5700 sequence detection system and accompanying software. The threshold for positivity was set at 1. The constitutively expressed cat (chloramphenicol acetyltransferase) gene of E. coli O42 was used as an internal standard for reactions involving this strain; the tet gene of pACYC184 was used as the standard for experiments involving pPic1. For each primer pair, a standard curve was generated by using known amounts of purified pic/set plasmid pPic1 (12). Unless otherwise indicated, experiments were performed with exponential-phase cells grown in L-broth.

Simulated human intestinal microbial ecosystem.

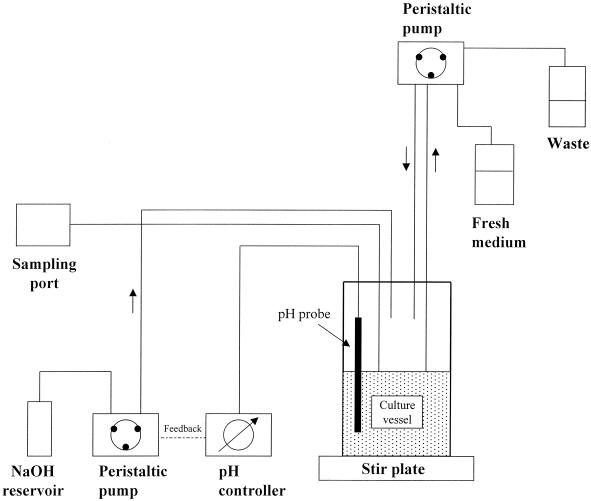

The simulated intestinal ecosystem was essentially that described in references 7 and 21, with the modifications described below (Fig. 1). The system comprised a continuous anaerobic culture of human feces maintained for at least 8 days at 37°C and pH 6.9 (Fig. 1). The growth medium of the culture has been shown previously to provide a stable culture of colonic bacteria and is designed to mimic the conditions of the human transverse colon (Table 3) (21). The volume of the culture was 500 ml, and flow was set to provide turnover of 1 culture volume/24 h. The inoculum consisted of 50 g of fresh feces, which was preincubated in 100 ml of fermentor medium for 6 h with stirring. Thereafter, 60 ml of this starter culture was inoculated into the main fermentor culture. The fecal inoculum was cultured quantitatively for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria as described in reference 32.

FIG. 1.

Diagram of the apparatus used for continuous culture of human fecal bacteria. See Materials and Methods for a detailed description.

TABLE 3.

Medium used for intestinal simulation culturesa

| Compound | Concn |

|---|---|

| NaCl | 30 mmol/liter |

| NaHCO3 | 5 mmol/liter |

| KCl | 5 mmol/liter |

| Bacto-Peptone (Difco) | 5 g/liter |

| Mucin (Sigma) | 2.5 g/liter |

| Starch | 0.6 g/liter |

| Glucose | 2.5 g/liter |

| Maltose | 3 g/liter |

| Hemin | 1 × 10−4 g/liter |

| Thioglycolic acid | 4.5 mmol/liter |

Modified from reference 21.

The culture in the fermentation vessel (Lofstrand Bactolift, 1 liter; Lofstrand Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.) was stirred continuously at 100 rpm by a magnetic stirrer. pH was monitored continuously by means of an electrode inserted through a port in the lid; the pH meter (Cole-Parmer Instruments, Vernon Hills, Ill.) was servocontrolled and maintained the desired setpoint by on-demand dispensation of 4 M NaOH via a peristaltic pump. Fresh medium was introduced into the culture vessel from a 2-liter reservoir by peristaltic pump. To help prevent retrograde bacterial growth, the medium was stored at pH 2. The entire system was maintained at a constant temperature of 37°C.

After the fermentor had been stabilized for at least 7 days, a sample was withdrawn and cultured again quantitatively for aerobic and anaerobic flora. Only if the bacteriologic profile was similar to that of the fecal inoculum was the experiment continued.

To study gene regulation in the fermentor, E. coli 042 harboring different lacZ fusion plasmids was introduced into the fermentation vessel. The preinoculation baseline β-galactosidase activity of the culture in the fermentation vessel was determined at steady state. This value was subtracted from all subsequent measurements. An overnight culture of E. coli 042 harboring a pRS551 lacZ fusion construct was then introduced into the fermentation vessel to an initial concentration of 5 × 106 CFU/ml, and the β-galactosidase activity was immediately sampled after mixing (time zero). The third and final measurement was carried out after 24 h of incubation. The number of E. coli 042 CFU was determined at time zero and after 24 h of incubation by plating dilutions on LB-agar plates containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml); cultures from the fermentation vessel without added E. coli 042 did not yield growth on these plates. Miller units were calculated according to the standard equation (20), except that the number of 042 CFU was converted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) value at the ratio of 1 OD600 = 109 CFU, determined to have a protein concentration of 0.2 μg/ml.

RESULTS

Transcriptional organization of pic and set genes.

The pic/set loci from S. flexneri 2a strain 2457T and EAEC strain 042 were cloned and sequenced previously (12). Both sequences comprise the pic structural gene of 4,116 nucleotides and, on the complementary strand, the setA gene (534 nucleotides) and the setB gene (186 nucleotides) (Fig. 2A). The loci from the two strains are 99% identical.

FIG. 2.

Organization of the pic/set locus. (A) Map of the chromosomal DNA fragment encoding pic and setBA and results of RT-PCR experiments to determine the initiation and termination sites of set transcription. Locations of nested set primers are indicated, along with presence (solid line) or absence (dotted line) of product generated by that primer pair. (B) Agarose gel electrophoresis demonstrating products of RT-PCR from the pic/set locus, using the primers illustrated in panel A. RNA was extracted from EAEC strain 042 and subjected to RT synthesis and cDNA amplification by standard PCR (cDNA lanes). A direct PCR step was carried out in parallel on 042 DNA to demonstrate the specificity of the PCR (DNA lanes). The primer pairs used are shown above the lanes. Molecular size markers are shown in the first lane of each gel; the sizes of some markers are indicated.

Sequence analysis suggests that upstream and downstream of pic lie insertion sequence-like elements (coordinates 275 to 496 and 5536 to the end in Fig. 2A), suggesting that transcription does not occur as part of a larger polycistronic message. This inference was confirmed by using RT-PCR: primers upstream or downstream of the pic structural gene did not generate products in RT-PCRs when paired with primers internal to the pic structural gene (not shown).

In contrast to pic, sequence analysis did not provide clues as to the likely start sites for setB or setA transcription. When subjected to RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 2) with a series of overlapping primer pairs from the upstream region of the set strand, only primer pair 21FRT and 22RRT failed to yield a product; these data suggest that the most upstream setB transcription start site lies between coordinates 4958 (the position of primer 20FRT) and 5218 (the position of primer 21FRT) in Fig. 2A, i.e., at least 1.6 kb upstream of the setB start codon and downstream of the pic stop codon on the opposite strand. Interestingly, of the setA downstream primers, only 26RRT failed to generate a product when paired with any other primer. This experiment suggests the presence of a transcriptional terminator of set mRNA upstream of the pic start codon on the opposite strand. Moreover, our RT-PCR data using overlapping primers suggested the presence of a setBA polycistronic mRNA, since primer pair 35RRT and 33FRT span the junction of the two open reading frames (ORFs).

RT-PCR experiments thus directed us toward the flanking regions of pic as the likely location of promoters for both pic and set, albeit on opposite strands. Primer extension experiments of the pic gene using automated sequencing protocols produced multiple potential start sites, without any clearly preferred site. One potential start site corresponded to the previously predicted σ70 promoter 19 bp upstream of the pic start codon (12), but additional potential sites were found upstream.

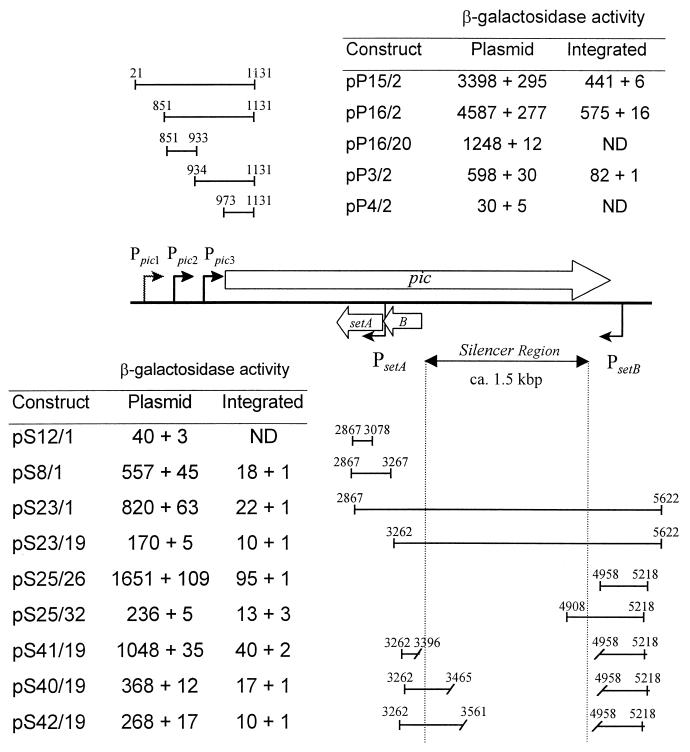

To better characterize the pic promoters, we cloned a series of pic upstream DNA fragments into the multiple cloning site of promoterless lacZ reporter vector pRS551 (Fig. 3) and electroporated the plasmids into EAEC strain 042. Three regions of interest were designated Ppic1 (between coordinates 21 and 851 of Fig. 3), Ppic2 (between coordinates 851 and 933), and Ppic3 (between coordinates 934 and 1131 and including the predicted promoter from reference 12). The transcriptional start site suggested by RT-PCR mapped between coordinates 537 and 693, within the Ppic1 region. However, lacZ fusion data suggested that this promoter was weak under the conditions tested (compare pP15/2 and pP16/2 in Fig. 3). Fragment Ppic2 yielded the highest lacZ expression levels, yet, a lacZ reporter fusion with Ppic2 alone (pP16/20) yielded threefold less β-galactosidase activity than a fusion including both the Ppic2 and Ppic3 regions (pP16/2). A fusion construct comprising only Ppic3 (pP3/2) yielded 20-fold-higher activity than a construct that did not include any of the predicted promoter regions (pP4/2). A fusion construct comprising only the Ppic1 region (21 to 851) yielded ninefold higher activity than pRS551 alone (not shown in the figure). These data suggest that multiple promoters direct pic expression.

FIG. 3.

β-Galactosidase activity derived from pic and set promoter fusions either in vector pRS551 transformed into EAEC 042 or as single-copy chromosomal integrations in E. coli K-12 strain TE2680. Values are the results of triplicate determination + standard deviation. The plasmids are described in Table 2. The numbers above the inserts refer to nucleotide positions with respect to Fig. 2. pic fusions are expressed from left to right and set fusions from right to left with respect to the lacZ gene. ND, not determined.

lacZ fusion experiments suggested the presence of a weak promoter just upstream of setA, between coordinates 2867 and 3267 in Fig. 3. This putative promoter was designated PsetA. No promoter activity was identified immediately upstream of setB. We therefore constructed a series of nested fragments of the setB upstream region as fusions in pRS551; these fragments extended from immediately upstream of setB to the setB transcriptional start site suggested by RT-PCR analyses. Among the setB fusions, plasmid pS25/26, comprising only the region downstream of the pic stop codon (coordinates 4958 to 5218), showed the highest β-galactosidase activity (1,651 Miller units); this activity was only observed when the fragment was cloned in the same orientation as setBA (i.e., the pic antisense orientation). We designated the promoter in this region PsetB.

Surprisingly, DNA fragments comprising the predicted PsetB promoter but also including additional downstream DNA suggested the presence of a repressing downstream regulatory element (DRE) or silencer region. A series of lacZ fusion constructs localized the setB DRE between positions 4958 and 3396 (Fig. 3). Analyzing a further series of deletions in the predicted DRE, we found that even small segments (ca. 50 to 60 bp) of this element extending to either end were sufficient to repress PsetB activity. The deletion of the entire predicted DRE (pS41/19) restored PsetBA activity almost to the levels exhibited by pS25/26.

Since all of the above fusions were constructed in high-copy-number plasmid pRS551, we transferred the lacZ fusions onto the chromosome of the E. coli K-12 strain TE2680 in single copy. The relative activities of the different fusions integrated into the TE2680 chromosome were similar to the activities observed in the extrachromosomal constructs (Fig. 3). These experiments suggest that our data were not influenced by copy number or topologic effects.

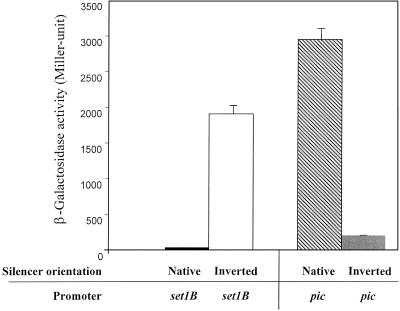

Orientation-specific regulation of pic and set genes by set silencer region.

Given that the setB DRE is embedded within the pic sequence, we asked whether the set silencer acted only on the set strand or instead bidirectionally, thereby also silencing pic expression. The lacZ reporter fusion plasmids pP16/2 (comprising Ppic2,3) and pS25/26 (PsetB) were used in these experiments. The silencer region was amplified by PCR and cloned in both orientations downstream of Ppic2,3 or PsetB. Results of β-galactosidase assays for all four constructs are shown in Fig. 4.

FIG. 4.

DNA strand-specific regulation of the pic and set genes by the set DRE silencer region. Results represent β-galactosidase measurements of at least triplicate determinations from L-broth cultures grown to late logarithmic phase; error bars represent 1 standard deviation. Test strains were EAEC strain 042 transformed with pic or set promoter DNA cloned upstream of the lacZ reporter in plasmid pRS551. Constructs used in these experiments were pS37/19 (setB promoter with the silencer in the native orientation); pS37/19-inverted (setB promoter with the silencer in the inverted orientation), pP37/19 (Ppic2,3 promoter region with the silencer in the native orientation), and pP37/19-inverted (Ppic2,3 promoters with the silencer in the inverted orientation).

As predicted, the silencer in the native orientation downstream of the setB promoter yielded low β-galactosidase activity. However, inversion of the silencer downstream of PsetB derepressed transcription by 46-fold. The silencer cloned in the inverted orientation (compared with the native) downstream of Ppic2,3 repressed transcription from the pic promoters by 14-fold. As expected, the silencer in the native orientation did not have any repressing effect on pic transcription. These results suggest that the silencer region represses transcription from either PsetB or Ppic2,3 in an orientation-specific manner.

Conditions affecting regulation of pic and set transcription.

We sought to identify conditions under which pic and set were maximally expressed. We tested lacZ expression of fusions pP15/2 (Ppic1,2,3) and pS23/19 (PsetB with silencer) under the following conditions: carbon starvation, anaerobiosis, iron limitation, and adherence to plastic, as well as varied pH, osmolarity, temperature, and growth phase. None of the conditions yielded PsetB activity significantly higher than that in the negative control, whereas a baseline level of pic expression was observed in all conditions at 37°C. Only logarithmic growth phase produced any detectable increase in pic expression over baseline (data not shown).

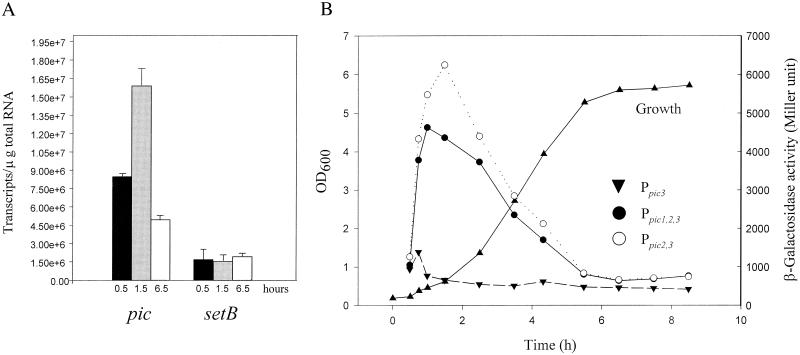

To characterize further the effect of growth phase in the EAEC strain 042 background, we employed real-time quantitative RT-PCR for pic and setBA transcripts. Whole-cell RNA was isolated from strain 042 at three time points after nutrient upshift (0.5, 1.5, and 6.5 h), and cDNA was synthesized as the template for quantitative RT-PCR. For the pic gene, we detected clear growth phase-dependent expression (Fig. 5A). However, the abundance of the setBA transcript displayed no significant change during growth, confirming that different signals are likely to be responsible for regulation of the pic and setBA genes.

FIG. 5.

(A) Effect of growth phase on pic and set expression as determined by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. RNA was extracted from E. coli 042 grown in L-broth for various times (0.5, 1.5, and 6.5 h) after 1:20 dilution of an overnight culture with fresh medium. cDNA was synthesized and subjected to quantitative RT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods. (B) β-Galactosidase activity of E. coli 042 harboring plasmid pP15/2 (Ppic1,2,3), pP16/2 (Ppic2,3), or pP3/2 (Ppic3) grown in L-broth and assayed at various times after dilution of overnight cultures with fresh medium.

We next used the lacZ reporter gene fusions pP15/2 (Ppic1,2,3), pP16/2 (Ppic2,3), and pP3/2 (Ppic3) transformed into E. coli 042 to determine which of the potential pic promoter regions were sensitive to growth phase-dependent regulation. As illustrated in Fig. 5B, only promoter Ppic2 appeared to be regulated by growth, exhibiting nearly fivefold induction between 0.5 and 1.5 h after nutrient upshift. The construct carrying Ppic3 alone yielded a modest activation (less than twofold) between 0.5 h and 1 h, and Ppic1 exhibited no detectable growth phase-dependent increase.

From these studies, we infer that (i) region Ppic1 is weak under all conditions tested, (ii) Ppic2 harbors a strong promoter inducible during growth, and (iii) the promoter within Ppic3 may be constitutively expressed but at low levels. These observations suggest that the Ppic2 promoter is the major source of pic expression.

Notably, we were unable to identify any in vitro conditions that induced expression of setB. Since silencing in E. coli typically involves binding of a histone-like protein to a DRE (3, 5, 14, 16, 18, 27, 35-38), we analyzed lacZ expression from construct pS23/19 (PsetB with silencer) in E. coli K-12 strains carrying known mutations in Fis, H-NS, or the H-NS homolog StpA. lacZ expression was not derepressed in any of these mutants compared with the E. coli K-12 parent (not shown).

Regulation of pic and set genes in EAEC, E. coli K-12, and S. flexneri.

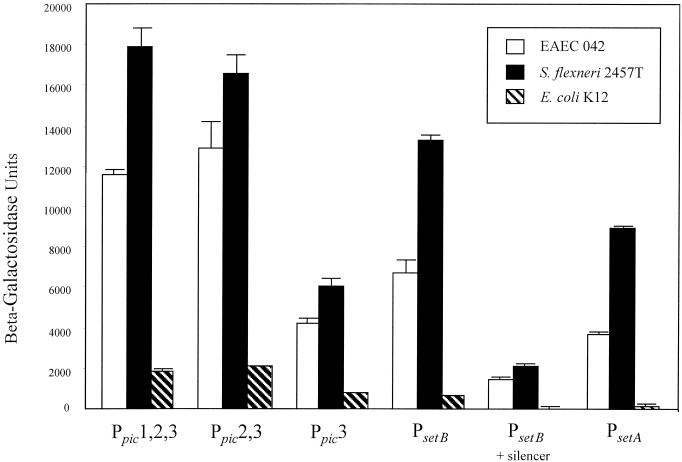

Maurelli et al. have reported that Shigella strains have undergone a large chromosomal deletion which results in augmentation of enterotoxic effects (19). This observation could be mediated in part by different regulatory controls of ShET1 operative in nonpathogenic E. coli versus Shigella spp. To address this hypothesis, lacZ reporter fusions with Ppic1,2,3 (pP15/2), Ppic2,3 (pP16/2), Ppic3 (pP3/2), PsetB (pS25/26), PsetB with the full silencer region (pS23/19), and PsetA (pS8/1) were transformed into EAEC strain 042, E. coli K-12, and S. flexneri 2457T (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Transcriptional regulation of pic and set in EAEC strain 042, E. coli K-12, and S. flexneri 2457T. Plasmids containing all three pic promoter regions (Ppic1,2,3), two pic promoter regions (Ppic2,3), the most downstream pic promoter region (Ppic3), the setB promoter (PsetB), the setB promoter with the DRE silencer region, or the setA promoter (PsetA) constructed in pRS551 were transformed into EAEC 042, S. flexneri 2457T, or E. coli K-12 and tested for β-galactosidase activity. Bacterial strains were grown to exponential phase in L-broth medium at 37°C to the late logarithmic phase. Bars represent results of at least three determinations; error bars represent 1 standard deviation.

Expression of pic from all promoter constructs was not significantly different between the pathogens EAEC and S. flexneri. However, pic expression in both the EAEC and Shigella backgrounds was substantially higher than in E. coli K-12 (at least fivefold higher for both Ppic1,2,3 and Ppic2,3 fusions). Similarly, expression of PsetB and PsetA promoters was slightly higher in S. flexneri than EAEC, but was higher in both backgrounds than in E. coli K-12. However, the silencing effect of the PsetB DRE was similar in all three backgrounds.

Regulation of setB transcription in a simulated human intestinal microbial ecosystem.

Using conventional approaches, we were not able to identify in vitro conditions or mechanisms that resulted in relief of PsetB silencing. We therefore expected either that the DRE was continually repressed, providing constitutively low levels of the ShET1 toxin, or that the bacterium would respond to some in vivo signal to induce toxin expression.

Given that no good animal models are available for either Shigella or EAEC infection, we tested our hypothesis in a simulated human intestinal ecosystem. Continuous-flow anaerobic cultures have been used previously to study the ecology of the complex intestinal ecosystem (7, 21). Adapting these published protocols, we established such a continuous anaerobic culture, inoculated with fecal material from healthy humans. The baseline β-galactosidase activity in the fermentor was determined before adding the test strain; the test strain, EAEC strain 042 harboring a lacZ reporter construct, was added to the vessel, and β-galactosidase activity was measured again. The last β-galactosidase determination was performed 24 h after addition of the test strain. Results are reported in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Activation of setB promoter in the simulated human intestinal microbial ecosystema

| Growth conditions | Mean β-galactosidase activity (Miller units) ± SD | Mean fold induction ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Simulator (anaerobic) | 44,290 ± 12,458 | 54 ± 15 |

| Simulator medium (aerobic) | 299 ± 31 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| LB medium (anaerobic) | 819 ± 166 | 1 ± 0.2 |

The test strain for all experiments was 042 (pS23/19). Results are means and SDs for three experiments. Fold induction represents β-galactosidase levels at 24 h compared with levels at time zero (time of inoculation of the culture).

When we introduced 042(pS23/19) into the simulator, the activity of the setB promoter, including its DRE, was increased up to 54-fold. In contrast, the same strain grown anaerobically in LB exhibited low β-galactosidase activity. Strain 042(pS23/19) grown aerobically in the simulator medium yielded low reporter activity. EAEC strain 042 transformed with the lacZ reporter plasmid (pRS551) alone did not show an increase in β-galactosidase activity in the fermentor (data not shown). Construct pS25/26, expressing only the PsetB promoter without the silencer, likewise did not show increased expression in the simulator, suggesting that relief of silencing was the dominant effect of the simulated intestinal environment.

DISCUSSION

The mucinase Pic and Shigella enterotoxin 1 are recently described factors which may play important roles in the virulence of S. flexneri 2a and EAEC. Whereas recent research has characterized aspects of the pathogenetic schemes for both of these pathogens, significant questions remain. Among these questions is the mechanism of the watery diarrhea phase seen in many cases of shigellosis. In addition, it is notable that S. flexneri 2a is the single most prevalent Shigella species worldwide (17); the mechanism for this increased virulence or transmissibility is not known, but the presence of pic/set in this serotype is one possible explanation.

In this study, we have characterized the transcriptional regulation of the pic and set genes on the complementary strands in S. flexneri strain 2457T and EAEC strain 042. Although the major promoter could not be assigned with certainty, the region upstream of pic yielded multiple fragments with promoter activity, and overall expression of pic was highest in the exponential growth phase. Promoter region Ppic3 contains a predicted σ70 promoter and increases lacZ expression in several different constructs, but with only slightly increased expression in exponential phase. Region Ppic2 does not contain a strongly predicted σ70 promoter, but it does confer strong growth phase-dependent lacZ expression in a reporter vector. RT-PCR suggests the presence of a transcript starting further upstream (Ppic1), and expression in a promoter-screening vector suggests that there is a functional promoter in this region as well. In toto, these observations suggest that the nutrient upshift and favorable temperatures experienced by the bacteria upon entry into the human intestine may induce pic expression from the major promoter, making the mucinase available at an early stage of the infection. It is possible that a second promoter (possibly Ppic3) ensures a constitutive low level of the mucinase, perhaps to facilitate the acquisition of nutrients once the bacterium is embedded within the mucus layer.

Expression studies of setBA yielded several surprises. Our RT-PCR data were most consistent with the existence of a ca. 4-kb transcript which encodes both setA and setB. We were not, however, able to demonstrate the existence of such a transcript by Northern blot, most likely because of the weak expression levels observed during in vitro growth. setA expression may initiate from a promoter immediately upstream of the structural gene or by readthrough from the setB promoter.

We found it notable that the strongest setB promoter was located at a site downstream of the pic stop codon on the opposite strand and that transcription from PsetB is silenced by a DRE. Well-characterized examples of such a downstream prokaryotic silencer have been reported for the proU operon of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (27), the hly operon of E. coli (15), the bgl promoter of E. coli (29), and the coo operon of enterotoxigenic E. coli (24). For proU and hly, the DRE spans some 200 bp, while for coo, the DRE is at least 900 bp long. The size of the bgl DRE has not been determined precisely. At 1,562 bp (by our definition), the DRE of the set operon would be the largest prokaryotic DRE yet delimited. We have also demonstrated that the setB DRE is orientation specific; only transcription starting from the setB promoter is silenced, whereas transcription of the pic gene is not repressed in the native orientation. On the other hand, inversion of the DRE leads to silencing of pic and not setB. In contrast, the bgl DRE can be inverted without impairing its activity (29). Also notably, the proU silencer does not regulate the tac promoter when cloned in a downstream position (27), whereas the bgl silencer is able to repress other promoters (lac and lacUV5).

The E. coli histone-like proteins Fis, H-NS, and StpA are apparently not individually responsible for the silencing effect of the setB DRE. This was surprising, since Fis and/or H-NS is essential for silencing of proU (27), bgl (29), and coo (2, 23, 24, 33). It is possible that these histone-like proteins may need to act in concert at the setB DRE or that another mechanism may be involved. Deletions which retained small portions from either end of the setB silencer region resulted in effective repression; only complete deletion of the region yielded relief of the repressed phenotype. The ability of small DNA regions to effect repression strongly argues against silencing by virtue of an RNA or DNA secondary structure.

We sought to identify in vitro conditions that relieved setB silencing, principally to suggest the timing of set expression in vivo. Surprisingly, were unable to do so by conventional methods. We therefore employed a novel approach which provides multiple in vivo-like conditions simultaneously, including temperature, pH, osmolarity, low oxygen tension, mucin, and the presence of quorum-sensing signals. We found that setB silencing was relieved (i.e., increased up to 54-fold) in a fermentor simulating the human intestine. The precise set of signals provided by the simulator are not so far apparent. Simulated human intestinal microbial ecosystems have been described by several groups (7, 21), but to our knowledge the simulator has not been used previously to study gene regulation.

Use of a simulated intestinal environment offers a number of obvious advantages in the study of gene regulation. The fermentor allows exposure of the pathogen to multiple conditions that are likely to be encountered in vivo. Just as importantly, the simulator can be modified to dissect the critical signals by removing or altering characteristics singly or in combination. The system is also more easily manipulated and sampled than an animal model, and significantly, the system can be tuned to the conditions of the human intestine, thereby avoiding erroneous observations drawn from interspecies variation in the flora or other conditions of the intestine. Further characterization of the expression of pic, set, and other virulence genes in the simulator is under way.

Although the pic and set loci are nearly identical in S. flexneri and EAEC, previous data suggest that the ShET1 toxin is more active in Shigella spp. Maurelli et al. have suggested that this observation is due to the deletion of a large region of the Shigella chromosome (the so-called black hole), which results in enhanced enterotoxic effects (19). These authors have suggested further that cadaverine, a product of the lysine decarboxylase reaction, may directly inhibit toxin activity. Our data suggest that the expression of the set genes may be enhanced in Shigella spp. and EAEC compared with E. coli K-12. Whether this effect is due to the loss of a negative regulator encoded on the black hole or to the presence of an additional pathogen-specific activator is not yet clear.

Our studies have characterized a novel locus in S. flexneri 2a and EAEC. It has not escaped our notice that additional virulence genes could be encoded by the setB mRNA. Indeed, two potential ORFs (>50 amino acids) are found within the DRE region; these are currently being characterized. Further studies to elucidate the roles of pic/set will likely provide new insights into the pathogenesis of Shigella spp. and EAEC.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service awards AI33096 and AI43615 to J.P.N.

We are grateful to Marlene Belfort for bacterial strains and Nicholas Carbonetti and Jay Mellies for critical review of the manuscript. We acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Suzanne Davis and Thomas J. Maher III.

Editor: D. L. Burns

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Hasani, K., K. Rajakumar, D. Bulach, R. Robins-Browne, B. Adler, and H. Sakellaris. 2001. Genetic organization of the she pathogenicity island in S. flexneri 2a. Microb. Pathog. 30:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caramel, A., and K. Schnetz. 2000. Antagonistic control of the Escherichia coli bgl promoter by FIS and CAP in vitro. Mol. Microbiol. 36:85-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Claret, L., and J. Rouviere-Yaniv. 1996. Regulation of HU alpha and HU beta by CRP and FIS in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 263:126-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Czeczulin, J. R., T. S. Whittam, I. R. Henderson, F. Navarro-Garcia, and J. P. Nataro. 1999. Phylogenetic analysis of enteroaggregative and diffusely adherent Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 67:2692-2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drlica, K., and J. Rouviere-Yaniv. 1987. Histonelike proteins of bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 51:301-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DuPont, H. L., M. M. Levine, R. B. Hornick, and S. B. Formal. 1989. Inoculum size in shigellosis and implications for expected mode of transmission. J. Infect. Dis. 159:1126-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards, C. A., B. I. Duerden, and N. W. Read. 1985. Metabolism of mixed human colonic bacteria in a continuous culture mimicking the human cecal contents. Gastroenterolog y 88:1903-1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elliott, T. 1992. A method for constructing single-copy lac fusions in Salmonella typhimurium and its application to the hemA-prfA operon. J. Bacteriol. 174:245-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fasano, A., F. R. Noriega, D. R. Maneval, S. Chanasongcram, S. Russell, S. Guandalini, and M. M. Levine. 1995. Shigella enterotoxin 1: an enterotoxin of S. flexneri 2a active in rabbit small intestine in vivo and in vitro. J. Clin. Investig. 95:2853-2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fasano, A., F. R. Noriega, F. M. Liao, W. Wang, and M. M. Levine. 1997. Effect of Shigella enterotoxin 1 (ShET1) on rabbit intestine in vitro and in vivo. Gut 40:505-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerrant, R. L., T. S. Steiner, A. A. Lima, and D. A. Bobak. 1999. How intestinal bacteria cause disease. J. Infect. Dis. 179(Suppl. 2):S331-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson, I. R., J. Czeczulin, C. Eslava, F. Noriega, and J. P. Nataro. 1999. Characterization of Pic, a secreted protease of S. flexneri and enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 67:5587-5596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong, M., Y. Gleason, E. E. Wyckoff, and S. M. Payne. 1998. Identification of two S. flexneri chromosomal loci involved in intercellular spreading. Infect. Immun. 66:4700-4710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jordi, B. J., and C. F. Higgins. 2000. The downstream regulatory element of the proU operon of Salmonella typhimurium inhibits open complex formation by RNA polymerase at a distance. J. Biol. Chem. 275:12123-12128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jubete, Y., J. C. Zabala, A. Juarez, and F. de la Cruz. 1995. hlyM, a transcriptional silencer downstream of the promoter in the hly operon of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:242-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan, M. A., and R. E. Isaacson. 1998. In vivo expression of the β-glucoside (bgl) operon of Escherichia coli occurs in mouse liver. J. Bacteriol. 180:4746-4749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotloff, K. L., J. P. Winickoff, B. Ivanoff, J. D. Clemens, D. L. Swerdlow, P. J. Sansonetti, G. K. Adak, and M. M. Levine. 1999. Global burden of Shigella infections: implications for vaccine development and implementation of control strategies. Bull. WHO 77:651-666. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lucht, J. M., P. Dersch, B. Kempf, and E. Bremer. 1994. Interactions of the nucleoid-associated DNA-binding protein H-NS with the regulatory region of the osmotically controlled proU operon of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 269:6578-6588. [PubMed]

- 19.Maurelli, A. T., R. E. Fernandez, C. A. Bloch, C. K. Rode, and A. Fasano. 1998. “Black holes” and bacterial pathogenicity: a large genomic deletion that enhances the virulence of Shigella spp. and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3943-3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics, p. 356-359. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 21.Molly, K., M. Vande Woestyne, and W. Verstraete. 1993. Development of a 5-step multichamber reactor as a simulation of the human intestinal microbial ecosystem. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 39:254-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moss, J. E., T. J. Cardozo, A. Zychlinsky, and E. A. Groisman. 1999. The selC-associated SHI-2 pathogenicity island of S. flexneri. Mol. Microbiol. 33:74-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukerji, M., and S. Mahadevan. 1997. Characterization of the negative elements involved in silencing the bgl operon of Escherichia coli: possible roles for DNA gyrase, H-NS, and CRP-cAMP in regulation. Mol. Microbiol. 24:617-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphree, D., B. Froehlich, and J. R. Scott. 1997. Transcriptional control of genes encoding CS1 pili: negative regulation by a silencer and positive regulation by Rns. J. Bacteriol. 179:5736-5743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nataro, J. P., Y. Deng, S. Cookson, A. Cravioto, S. J. Savarino, L. D. Guers, M. M. Levine, and C. O. Tacket. 1995. Heterogeneity of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli virulence demonstrated in volunteers. J. Infect. Dis. 171:465-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nataro, J. P., T. Steiner, and R. L. Guerrant. 1998. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 4:251-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Overdier, D. G., and L. N. Csonka. 1992. A transcriptional silencer downstream of the promoter in the osmotically controlled proU operon of Salmonella typhimurium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:3140-3144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 29.Schnetz, K. 1995. Silencing of Escherichia coli bgl promoter by flanking sequence elements. EMBO J. 14:2545-2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29a.Sheikh, J., S. Hicks, M. Dall’Agnol, A. D. Phillips, and J. P. Nataro. 2001. Roles for Fis and YafK in biofilm formation by enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 41:983-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simons, R. W., F. Houman, and N. Kleckner. 1987. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene 53:85-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steiner, T. S., A. A. Lima, J. P. Nataro, and R. L. Guerrant. 1998. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli produce intestinal inflammation and growth impairment and cause interleukin-8 release from intestinal epithelial cells. J. Infect. Dis. 177:88-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Summamen, P., E. J. Barron, D. M. Citron, C. A. Strong, H. M. Wexler, and S. M. Finegold. 1993. Wadsworth anaerobic bacteriology manual, 5th ed., p. 140-146. Star Publishing Co., Belmont, Calif.

- 33.Ueguchi, C., and T. Mizuno. 1993. The Escherichia coli nucleoid protein H-NS functions directly as a transcriptional repressor. EMBO J. 12:1039-1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vokes, S. A., S. A. Reeves, A. G. Torres, and S. M. Payne. 1999. The aerobactin iron transport system genes in S. flexneri are present within a pathogenicity island. Mol. Microbiol. 33:63-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu, J., and R. C. Johnson. 1995. Fis activates the RpoS-dependent stationary-phase expression of proP in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:5222-5231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu, J., and R. C. Johnson. 1995. aldB, an RpoS-dependent gene in Escherichia coli encoding an aldehyde dehydrogenase that is repressed by Fis and activated by Crp. J. Bacteriol. 177:3166-3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu, J., and R. C. Johnson. 1997. Cyclic AMP receptor protein functions as a repressor of the osmotically inducible promoter proP P1 in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:2410-2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamada, H., T. Yoshida, K. Tanaka, C. Sasakawa, and T. Mizuno. 1991. Molecular analysis of the Escherichia coli hns gene encoding a DNA-binding protein, which preferentially recognizes curved DNA sequences. Mol. Gen. Genet. 230:332-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]