Abstract

A key issue in health provision is the approach to health inequalities. In the UK, black and ethnic minority populations are disadvantaged in this respect. We obtained annual/public health reports from 13 health authorities (HAs) and 22 primary care trusts/groups (PCT/Gs) serving conurbations with large black and ethnic minority populations, and examined them for mention of special health issues for these groups and the action being taken. 22 of the 35 reports referred to such issues but only 17 referred to special initiatives; the most frequently mentioned were diabetes and coronary heart disease. We recommend that HAs and PCT/Gs serving large black and ethnic minority populations state specifically in their annual reports their awareness of health-equality issues and the action being taken to address them.

INTRODUCTION

In 1991, according to the Census, about 6% of the population of England and Wales were of black and ethnic minority origin1. Today the proportion is likely to be higher—partly because of the higher birth rate in these groups, but partly also because 1.2 million people were missed from the 1991 estimates. People from ethnic minorities tend to perceive themselves as less healthy than those in the general UK population2; for example, those from the Indian subcontinent have a substantially higher rate of coronary heart disease. The present British government understands that its aim to increase life expectancy and number of years of freedom from illness in the population cannot be achieved without addressing the issue of inequalities—in other words, improving the health of those who are worst off. We have conducted a survey to determine the approaches to this issue being adopted by health authorities and primary care trusts/groups in districts of England with large black and ethnic minority populations.

METHODS

We used data from the 1991 Census to identify conurbations with a high proportion (10-45%) of people of black and ethnic minority origin. 20 health authorities (HAs) and 64 primary care trusts or groups (PCT/Gs) from such conurbations were asked to supply copies of their annual/public health reports. Each of the reports received was examined to determine which aspects of black and ethnic minority healthcare were mentioned and what action was being taken to address them.

RESULTS

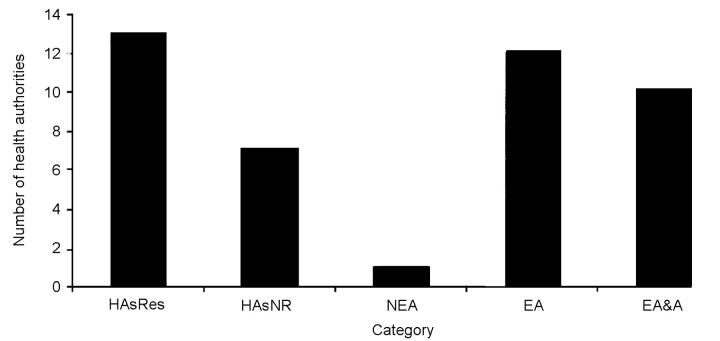

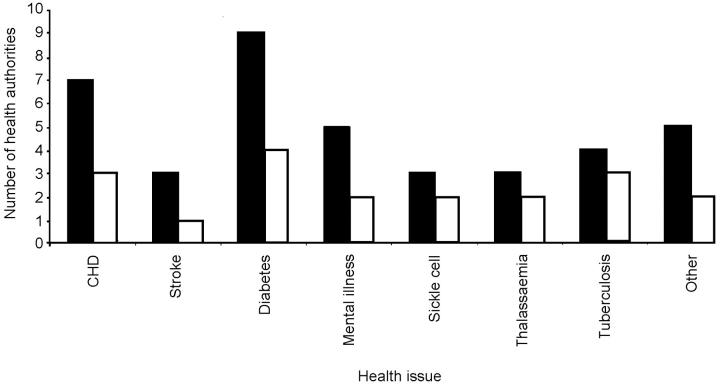

Replies were received from 13 HAs and 22 PCT/Gs. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the response rates, mentions of issues and references to action taken. 12 (92%) of the 13 HA reports identified health issues for black and ethnic minority groups and 9 specified initiatives to address them. Health concerns mentioned were coronary heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, mental health, sickle-cell anaemia, thalassaemia, tuberculosis, and inequalities in access to services. The most frequently mentioned concern was diabetes (Figure 3), but only 4 reports referred to special initiatives or programmes to deal with this disorder. 7 (54%) of these reports mentioned inequalities of access to health services, of which 5 described current or planned measures to deal with this issue.

Figure 1.

Reports from health authorities. HasRes=health authorities responding; HasNR=HAs not responding; NEA=not stating ethnic awareness; EA=ethnic awareness; EA&A=ethnic awareness and action

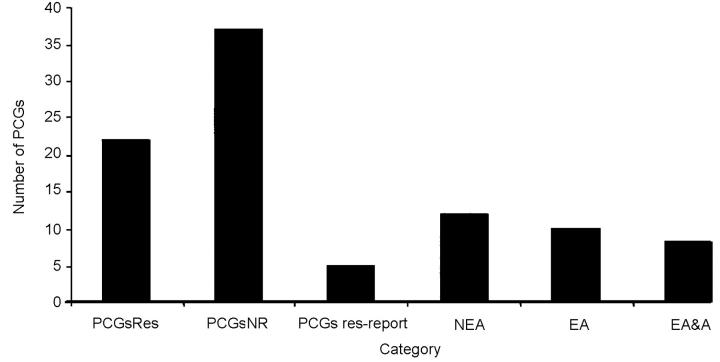

Figure 2.

Reports from primary care groups/trusts. PCGRes=PCGs responding; PCGNR=PCGs not responding. For other abbreviations see legend to Figure 1

Figure 3.

Number of health authorities identifying special healthcare issues (▪) and number taking action (□)

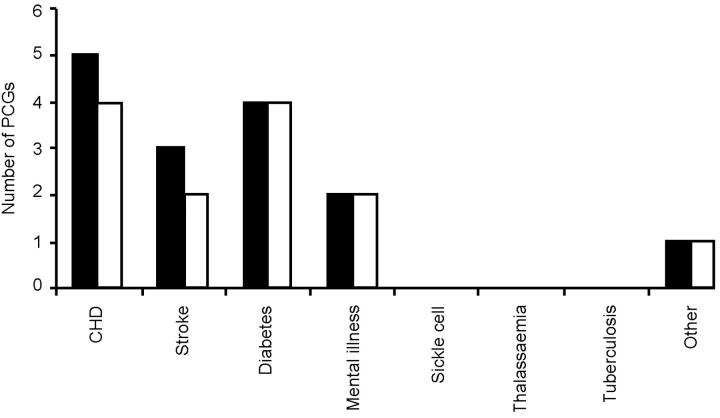

Of the 22 PCT/Gs who responded, 10 (45%) referred in their reports to special health issues in black and ethnic minority populations and 8 were addressing these issues (Figure 4). The issues most commonly identified were high rates of coronary heart disease (5 reports) and diabetes (4); just 4 reports described action being taken to address these disorders. 5 mentioned inequalities of access to health services and the same number referred to initiatives, either underway or planned, to counter them.

Figure 4.

Number of primary care groups/trusts identifying special healthcare issues (▪) and number taking action (□)

DISCUSSION

There was a clear discrepancy between the number of reports mentioning healthcare issues for black and ethnic minority communities and the number identifying actions being taken. Even for coronary heart disease and diabetes—the most frequently discussed issues—only one-third of the reports referred to special interventions. Because many of the authorities (especially PCT/Gs) did not respond to our requests for reports, the results must be interpreted cautiously. Seemingly the PCT/Gs were less sensitive than HAs to these matters—a finding that might reinforce concerns about loss of the public health function in the latest National Health Service reorganization4—but these are early days for the PCT/Gs.

We recommend that HAs and PCT/Gs with a large black and ethnic minority population in their territory should state specifically, in their annual reports, their awareness of the major health issues for these populations. They should identify the high-priority health needs and the actions being taken to address inequalities, both of disease incidence and of access to services. Explicit commitments of this sort will help promote confidence, in these communities, that health inequalities are being taken seriously.

References

- 1.Balarajan R. Ethnic Diversity in England and Wales: an Analysis by Health Authorities Based on the 1991 Census. London: NIESH, 1997

- 2.Department of Health. Saving Lives, our Healthier Nation. London: Stationery Office, 1999

- 3.Health Education Authority. Black and Ethnic Minority Groups in England—Health and Lifestyles. Exeter: Wheatons, 1994

- 4.Holland WW. A dubious future for public health? J R Soc Med 2002;95: 182-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Memon M, Abbas F. Reducing health risks in ethnic minorities. Nurs Times 1999;95: 49-51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Memon M, Abbas F, Singh I, Gupta R. Restricted access. Health Serv J 2001;111: 22-4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]