Abstract

Salmonella enterica serovar Arizona (S. enterica subspecies IIIa) is a common Salmonella isolate from reptiles and can cause serious systemic disease in humans. The spv virulence locus, found on large plasmids in Salmonella subspecies I serovars associated with severe infections, was confirmed to be located on the chromosome of serovar Arizona. Sequence analysis revealed that the serovar Arizona spv locus contains homologues of spvRABC but lacks the spvD gene and contains a frameshift in spvA, resulting in a different C terminus. The SpvR protein functions as a transcriptional activator for the spvA promoter, and SpvB and SpvC are highly conserved. The analysis supports the proposal that the chromosomal spv sequence more closely corresponds to the ancestral locus acquired during evolution of S. enterica, with plasmid acquisition of spv genes in the subspecies I strains involving addition of spvD and polymorphisms in spvA.

Salmonella enterica serovar Arizona (S. enterica subspecies IIIa) is naturally found in reptiles but also causes outbreaks of salmonellosis in turkeys and sheep and can produce both enteritis and serious disseminated disease in humans (6, 7, 18, 20, 28, 35). Reptiles frequently harbor serovar Arizona as a commensal organism, but pathological responses to infection have also been reported, and the bacteria seem capable of vertical transmission through infection of oviduct tissue (7). Many human infections can be traced to contact with reptiles or ingestion of various reptile products, particularly from rattlesnakes (3, 27, 29). Patients with depressed CD4-mediated T-cell immunity, such as those infected with human immunodeficiency virus, are particularly susceptible to the development of serious and persistent systemic infections with serovar Arizona after ingestion of contaminated products.

The virulence determinants of serovar Arizona are poorly understood. However, the ability of this organism to cause extraintestinal infection in both reptiles and humans is consistent with recent evidence that this subspecies contains the spv virulence gene locus (5). The spv genes have been extensively studied in serovars of the S. enterica subspecies I lineage, including serovars Typhimurium, Dublin, Enteritidis, Choleraesuis, and Gallinarum-Pullorum (15, 16, 17). The spv loci in these strains are highly homologous, consisting of the transcriptional regulator spvR and four structural genes, spvABCD. The SpvB protein is an ADP ribosyltransferase that modifies actin and destabilizes the cytoskeleton of infected cells (22, 34) and appears to be primarily responsible for the spv virulence phenotype (22). In serovar Dublin, the spv genes increase the severity of both intestinal and systemic disease, while, in other serovars examined, a consistent enhancement of systemic virulence has been reported (1, 9, 16, 24). Furthermore, extraintestinal infections caused by serovar Typhimurium in humans are significantly associated with strains that carry the spv locus (11).

Within the genus Salmonella, the spv locus exhibits a distinct phylogenetic distribution. The spv genes are absent from Salmonella bongori and are present in subspecies I, II, IIIa, IV, and VII of S. enterica (5). Within subspecies I, the lineage responsible for the vast majority of human salmonellosis cases, the spv genes are located exclusively on large virulence plasmids present in certain serovars. In contrast, subspecies II, IIIa, IV and VII appear to carry spv genes in the chromosome (5). Moreover, sequence analysis of a portion of the spvA gene reveals polymorphisms consisting of insertions and deletions, as well as base substitutions, among the subspecies (5). Based on the demonstrated importance of serovar Arizona as a human pathogen, we investigated the structure of the entire spv locus in this subspecies.

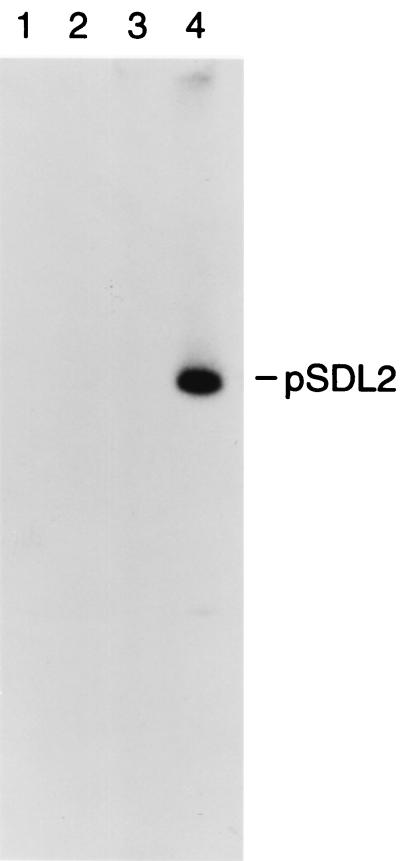

A recent report concluded (on the basis of a pulsed-field electrophoresis analysis) that the spv genes of serovar Arizona were located in the chromosome (5). However, this study did not rule out the possibility that the spv locus was carried on a very large plasmid, since the patterns of spv hybridization were similar for whole-cell DNA run either undigested or digested with I-CeuI. To establish the chromosomal location of the spv locus in serovar Arizona, we used transverse alternating-field electrophoresis (TAFE) to resolve very large DNA molecules (14). Cells of serovar Arizona strains 2323, 2334, and 2335, as well as serovar Dublin Lane, were lysed in agarose plugs, run on TAFE, transferred to a nylon membrane, and hybridized to a 4-kb EcoRI probe fragment containing the spvA, -B, and -C genes from serovar Dublin (30). The result, shown in Fig. 1, demonstrates the absence of extrachromosomal DNA that hybridizes to the spv probe in lanes containing the undigested whole-cell DNA of the serovar Arizona strains, while a strongly hybridizing band representing the pSDL2 plasmid is seen in the DNA containing the spv locus from serovar Dublin. This result is consistent with our inability to demonstrate an extrachromosomal locus of the spv genes (data not shown) using DNA isolation techniques (8, 19, 26) specifically designed to detect large plasmid molecules.

FIG. 1.

TAFE showing undigested serovar Arizona whole-cell DNA hybridized to the spv gene probe from serovar Dublin. Lane 1, serovar Arizona 2323; lane 2, serovar Arizona 2334; lane 3, serovar Arizona 2335; lane 4, serovar Dublin Lane containing pSDL2 (2).

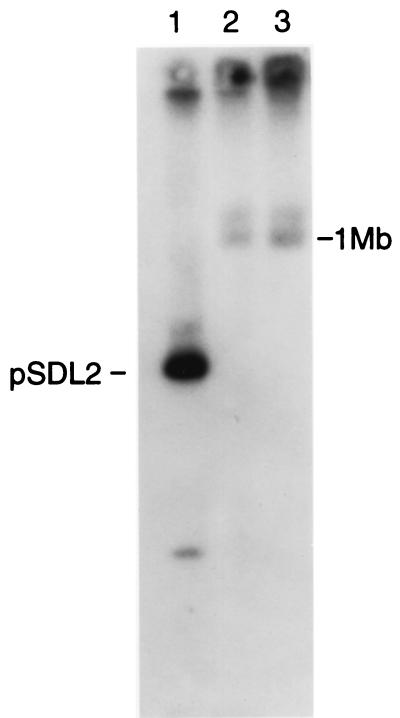

Further evidence that the spv locus is located in the serovar Arizona chromosome was obtained by digesting the whole-cell DNA with I-CeuI, an enzyme that recognizes an extended sequence within the rrl rRNA genes of Salmonella strains (25). Figure 2 shows the result of hybridizing the spv probe to I-CeuI digests of serovar Dublin and serovar Arizona strains 2323 and 2334, resolved by TAFE. Both serovar Arizona strains contain a large I-CeuI fragment, greater than 1 Mb in size, that hybridizes to the spv probe. These results prove that the spv genes in serovar Arizona strains are located on a very large I-CeuI fragment of the chromosome.

FIG. 2.

Hybridization of the spv gene probe to serovar Arizona DNA digested with I-CeuI. Lane 1, serovar Dublin Lane containing pSDL2; lane 2, serovar Arizona 2323; lane 3, serovar Arizona 2334. The faint band running larger than 1 Mb in lanes 2 and 3 appears to be the result of a partial digest.

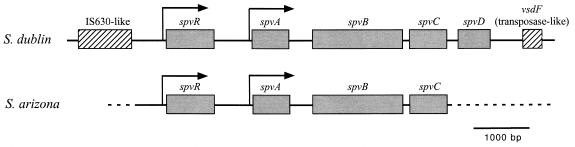

For further analysis, the spv locus from a recent clinical isolate, serovar Arizona strain 5705A, was cloned on cosmid pLAFR2 (23) by partial Sau3A digestion of whole-cell DNA. Two clones containing the spv region were identified by colony hybridization. Both cosmids contained common 6.5- and 2.2-kb EcoRI fragments that hybridized to the spvABC and spvR probes, respectively. These fragments were sequenced, and the results are shown in Fig. 3. Close homology to the serovar Dublin pSDL2 spv sequence (21) was found in a region from serovar Arizona extending 515 bp upstream from the spvR start codon to a site only 3 bp downstream from the spvC stop codon (96% conserved residues overall). The spvD gene is absent from the serovar Arizona sequence. Southern blot hybridization of whole-cell DNA demonstrated that the spvD gene is missing from the serovar Arizona genome (data not shown). The flanking regions upstream and downstream of the serovar Arizona spv locus do not show significant extended homology with any DNA sequences in the database or with the S. enterica serovar Typhi sequence. The translated DNA sequence downstream from the serovar Arizona spvC gene shows fragments of open reading frames related to transposases and a resolvase, suggesting that this region represents a degenerated insertion element.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the spv loci from serovar Dublin (S. dublin) (a subspecies I strain) and serovar Arizona (S. arizona) (subspecies IIIa). The homology (indicated by the solid serovar Arizona line) extends from 515 bp upstream of the spvR promoter to 3 bp after the spvC stop codon. The noncoding regions also showed similar homology to the coding regions, with only two short gaps in locations with no known functional significance. The nonhomologous serovar Arizona sequence is shown by the dashed line. Neither of the flanking insertion sequence-like elements in serovar Dublin is present in the serovar Arizona region that was sequenced.

The regulatory regions of the spvR and spvA promoters are highly conserved between the subspecies I sequences and serovar Arizona. The transcriptional activator SpvR binds to well-defined sequences upstream of the −25 position in both promoters, and promoter mutations within these sites have been isolated and characterized in serovar Dublin and serovar Typhimurium (12, 13, 32). There is a 1-bp difference between the serovar Typhimurium and serovar Dublin spvR promoter sequences, and serovar Arizona matches the serovar Typhimurium sequence. In the spvA regulatory region, the serovar Typhimurium and serovar Dublin sequences are identical, but serovar Arizona has an A-to-G change at −13 and two A-to-G differences in the promoter-proximal end of the SpvR binding region (12). The significance of these changes remains to be established, since none of them corresponds to the promoter-defective mutations previously reported for serovar Dublin and serovar Typhimurium (13, 32).

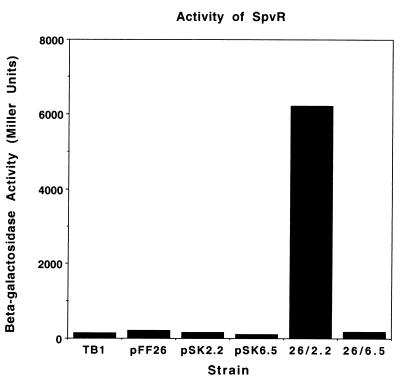

The amino acid sequences of SpvR from five different subspecies I serovars differ at only 4 positions out of 297 residues. At each of these, the serovar Arizona sequence conforms to the consensus of the subspecies I sequences. However, serovar Arizona differs from the subspecies I serovars at 5 other positions which are exactly conserved in subspecies I strains. Therefore, we determined whether the SpvR protein from serovar Arizona was able to activate transcription from the spvA promoter of serovar Dublin. The 2.2-kb EcoRI fragment containing the serovar Arizona spvR was cloned on pBluescript II SK(+) and was transformed into Escherichia coli TB1 containing the spvA promoter reporter plasmid pFF26 (10). As a control, the 6.5-kb fragment carrying the serovar Arizona spvABC region was also cloned into pBluescript. The result of a representative β-galactosidase assay is shown in Fig. 4 and demonstrates that SpvR from serovar Arizona (encoded by the 2.2-kb fragment) can activate the serovar Dublin spvA promoter on pFF26. Controls using the 6.5-kb fragment gave background levels of spvA promoter activation.

FIG. 4.

Activation of the spvA promoter reporter construct by the serovar Arizona SpvR protein. A representative experiment is shown. pSK2.2 and pSK6.5 refer to the 2.2-kb (spvR) and 6.5-kb (spvABC) EcoRI fragments from serovar Arizona. All plasmids were assayed in E. coli TB1.

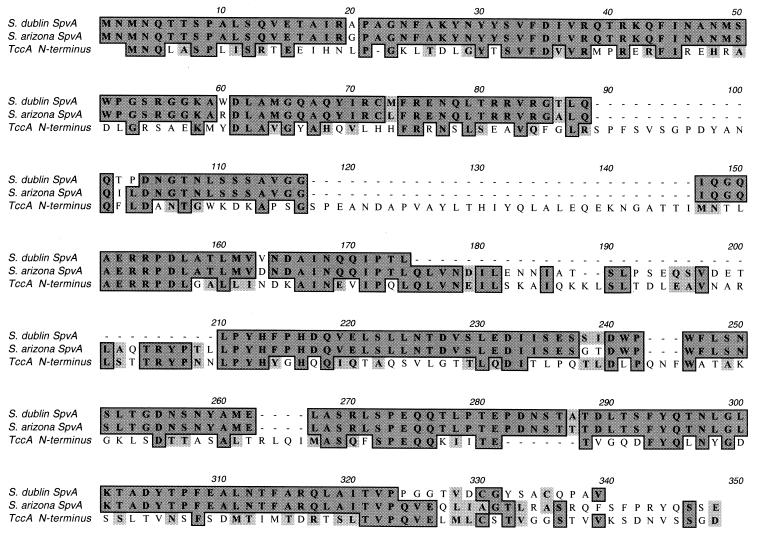

The sequence of an internal fragment of the serovar Arizona SpvA protein has been previously reported as containing an additional 33-amino-acid segment not present in the SpvA proteins of subspecies I strains (5). Our sequence of the complete SpvA protein from serovar Arizona reveals a frameshift in the C-terminal region resulting in a different protein sequence and slightly longer C terminus than in the subspecies I SpvA proteins. Interestingly, the Salmonella SpvA proteins share significant homology with the TccA component of an insecticidal toxin from Photorhabdus luminescens (4). Figure 5 shows a multiple alignment of the SpvA proteins from serovar Dublin and serovar Arizona with TccA. The serovar Arizona SpvA protein and TccA share two key sequence features that are different from SpvA from serovar Dublin. The 33-amino-acid segment present in serovar Arizona (residues 175 to 209) is also found in TccA but is missing from serovar Dublin. Likewise, the C-terminal frameshift change in serovar Arizona is also present in TccA, following residue 323. This comparison suggests that the common ancestor of TccA and the SpvA proteins also contained these two sequence features and that the deletion and frameshift mutations arose during evolution of the serovar Dublin and other subspecies I spvA genes.

FIG. 5.

Multiple alignment of the SpvA proteins from serovar Dublin (S. dublin) and serovar Arizona (S. arizona) with the TccA protein of P. luminescens. The numbers refer to residues of the composite sequence. Dark boxes indicate identical residues, and light shading shows similar residues.

Both SpvB and SpvC are highly conserved between serovar Arizona and the corresponding subspecies I virulence plasmid genes. The serovar Arizona SpvB protein differs at only 20 of its 593 residues from the consensus subspecies I sequence. Two of these are additional prolines in the polyproline bridge that separates the N-terminal domain from the C-terminal ADP-ribosylating domain (22). SpvC from serovar Arizona contains 6 differences out of 241 residues. As noted above for SpvR and SpvA, SpvB and SpvC from the subspecies I plasmids are more closely related to each other than to serovar Arizona, a finding consistent with the ancestral status of the serovar Arizona locus.

We have provided definitive evidence that the serovar Arizona spv locus is in the chromosome. Sequence analysis of the flanking regions comprising 370 bp upstream from the region of homology to the subspecies I strains and about 2 kb downstream do not reveal extended homologies with available Salmonella sequences, suggesting that there may be an extended region around the serovar Arizona locus that is not present in the chromosomes of Salmonella strains of the subspecies I lineage. We propose that the spv locus represents a pathogenicity island in serovar Arizona.

Within the spv region, the most significant differences between serovar Arizona and the subspecies I strains are the absence of spvD and polymorphisms in spvA. Earlier studies have implicated only a minor virulence role for spvD in murine infections (31). However, it is possible that this gene could have a function in other hosts or environments. Based primarily on polymorphisms in the spvA locus, Boyd and Hartl (5) proposed that the chromosomal serovar Arizona spv sequence corresponds more closely than the subspecies I plasmid sequence to the ancestral locus that was acquired by the S. enterica lineage after divergence from S. bongori. Subspecies I, IIIb, VI, and VII and strains of IV would then have lost their chromosomal spv locus, to be regained on a family of virulence plasmids by certain serovars of subspecies I. Our results are consistent with this model, given the additional conditions that spvD was also acquired by the plasmid locus and that spvA suffered a frameshift mutation in addition to the previously reported central in-frame deletion (5) during the evolution of the plasmid spv genes. Comparison of the serovar Arizona SpvA sequence with TccA of P. luminescens demonstrates that the common ancestor contained both the central region and the original C-terminal reading frame. This model suggests that spvA had a role in the ancestral lineage and perhaps in present-day serovar Arizona strains but either tolerates extensive polymorphism or is dispensable in plasmid-encoded loci. The latter possibility is supported by mutational analysis indicating that spvA is not required for virulence in mice (31).

The lack of a feasible animal model for serovar Arizona virulence precludes a definitive analysis of the role of the spv genes in this subspecies. However, several indirect lines of evidence support the functional significance of the spv locus that we have characterized. The SpvR, SpvB, and SpvC genes are all intact and highly conserved relative to the subspecies I counterparts. We also demonstrated that the serovar Arizona SpvR protein is a functional activator of the spvA promoter. Finally, serovar Arizona is associated with the same severe systemic clinical disease as the spv-containing subspecies I strains serovar Typhimurium, serovar Enteritidis, serovar Dublin, and serovar Choleraesuis (3, 20, 27, 28, 29). The key pathogenic mechanism appears to involve the induction of cytotoxicity due to actin depolymerization by the SpvB protein, enhancing systemic growth of the organism (22). This property of the spv locus may have enabled certain Salmonella lineages to adapt to particular ecological niches. A major role of the spv genes could be to promote transmission of the organism through systemic spread and localization in key target tissues. Serovar Dublin is host adapted to cattle, and colonization of the udder, with intermittent shedding in milk, appears to be a major mechanism for long-term persistence of the organism in herds (33). In nature, serovar Arizona infection of reptiles is widespread but often is present without manifestation of disease. Systemic spread with transovarial passage of serovar Arizona in snakes has been postulated as a major mechanism of transmission (7).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI-32178 and DK35108). Michael Kurth was the recipient of a Science Teacher Summer Research Fellowship from the American Society for Clinical Investigation.

Editor: J. T. Barbieri

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrow, P. A., J. M. Simpson, M. A. Lovell, and M. M. Binns. 1987. Contribution of Salmonella gallinarum large plasmid toward virulence in fowl typhoid. Infect. Immun. 55:388-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beninger, P. R., G. Chikami, K. Tanabe, C. Roudier, J. Fierer, and D. G. Guiney. 1988. Physical and genetic mapping of the Salmonella dublin virulence plasmid pSDL2. Relationship to plasmids from other Salmonella strains. J. Clin. Investig. 81:1341-1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatt, B. D., M. J. Zuckerman, J. A. Foland, S. M. Polly, and R. K. Marwah. 1989. Disseminated Salmonella arizona infection associated with rattlesnake meat ingestion. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 84:433-435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowen, D., T. A. Rocheleau, M. Blackburn, O. Andreer, E. Golubera, R. Bhartia, and R. H. ffrench-Constant. 1998. Insecticidal toxins from the bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens. Science 280:2129-2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyd, E. F., and D. L. Hartl. 1998. Salmonella virulence plasmid: modular acquisition of the spv virulence region by an F-plasmid in Salmonella enterica subspecies I and insertion into the chromosome of subspecies II, IIIa, IV and VII isolates. Genetics 149:1183-1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caldwell, M. E., and D. L. Ryerson. 1939. Salmonellosis in certain reptiles. J. Infect. Dis. 65:242-245. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiodini, R. J. 1982. Transovarian passage, visceral distribution, and pathogenicity of salmonella in snakes. Infect. Immun. 36:710-713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Currier, T. C., and E. W. Nester. 1976. Isolation of covalently closed circular DNA of high molecular weight from bacteria. Anal. Biochem. 76:431-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danbara, H., R. Moriguchi, S. Suseke, Y. Tamura, M. Kijima, K. Oishi, H. Matsui, A. Abe, and M. Kakamura. 1992. Effect of 50 kilobase-plasmid, pKD5C50, of Salmonella choleraesuis RF-1 strain on pig septicemia. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 54:1175-1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang, F. C., M. Krause, C. Roudier, J. Fierer, and D. G. Guiney. 1991. Growth regulation of a Salmonella plasmid gene essential for virulence. J. Bacteriol. 173:6783-6789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fierer, J., M. Krause, R. Tauxe, and D. Guiney. 1992. Salmonella typhimurium bacteremia: association with the virulence plasmid. J. Infect. Dis. 166:639-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grob, P., and D. G. Guiney. 1996. In vitro binding of the Salmonella dublin virulence plasmid regulatory protein SpvR to the promoter regions of spvA and spvR. J. Bacteriol. 178:1813-1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grob, P., D. Kahn, and D. G. Guiney. 1997. Mutational characterization of promoter regions recognized by the Salmonella dublin virulence plasmid regulatory protein SpvR. J. Bacteriol. 179:5398-5406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guiney, D. G., and P. Hasegawa. 1992. Transfer of conjugal elements in oral black pigmented Bacteroides (Prevotella) spp. involves DNA rearrangements. J. Bacteriol. 174:4853-4855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guiney, D. G., F. C. Fang, M. Krause, and S. Libby. 1994. Plasmid-mediated virulence genes in non-typhoid Salmonella serovars. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 124:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guiney, D. G., F. C. Fang, M. Krause, S. Libby, N. A. Buchmeier, and J. Fierer. 1995. Biology and clinical significance of virulence plasmids in Salmonella serovars. Clin. Infect. Dis. 21(Suppl. 2):S146-S151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gulig, P. A., H. Danbara, D. G. Guiney, A. J. Lax, F. Norel, and M. Rhen. 1993. Molecular analysis of spv virulence genes of the Salmonella virulence plasmids. Mol. Microbiol. 7:825-830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall, M. L. M., and B. Rowe. 1992. Salmonella arizona in the United Kingdom from 1966-1990. Epidemiol. Infect. 108:59-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansen, J. B., and R. H. Olsen. 1978. Isolation of large bacterial plasmids and characterization of the P2 incompatibility group plasmids pMG1 and pMG5. J. Bacteriol. 135:227-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson, R. H., L. I. Lutwick, G. A. Huntley, and K. L. Vosti. 1976. Arizona hinshawii infections. Ann. Intern. Med. 85:587-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krause, M., C. Roudier, J. Fierer, J. Harwood, and D. Guiney. 1991. Molecular analysis of the virulence locus of the Salmonella dublin plasmid pSDL2. Mol. Microbiol. 5:307-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lesnick, M. L., N. E. Reiner, J. Fierer, and D. G. Guiney. 2001. The Salmonella spvB virulence gene encodes an enzyme that ADP-ribosylates actin and destabilizes the cytoskeleton of eukaryotic cells. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1464-1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Libby, S. J., W. Goebel, A. Ludwig, F. Bowe, N. Buchmeier, G. Songer, F. Fang, D. Guiney, and F. Heffron. 1994. A cytolysin from Salmonella typhimurium is required for survival in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:489-493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Libby, S. J., L. G. Adams, T. A. Ficht, C. Allen, H. A. Whitford, N. A. Buchmeier, S. Bossie, and D. G. Guiney. 1997. The spv genes on the Salmonella dublin virulence plasmid are required for severe enteritis and systemic infection in the natural host. Infect. Immun. 65:1786-1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu, S.-L., A. Hessel, and K. E. Sanderson. 1993. Genomic mapping with I-Ceu I, an intron-encoded endonuclease specific for genes for ribosomal RNA, in Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli, and other bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:6874-6878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer, R., D. Figurski, and D. R. Helinski. 1977. Physical and genetic studies with restriction endonucleases on the broad host-range plasmid RK2. Mol. Gen. Genet. 152:129-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noskin, G. A., and J. T. Clarke. 1990. Salmonella arizonae bacteremia as the presenting manifestation of human immunodeficiency virus infection following rattlesnake meat ingestion. Rev. Infect. Dis. 12:514-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petru, M. A., and D. D. Richman. 1981. Arizona hinshawii infection of an atherosclerotic abdominal aorta. Arch. Intern. Med. 141:537-538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riley, K. B., D. Antoniskis, R. Mavis, and J. M. Leedom. 1988. Rattlesnake capsule-associated Salmonella arizona infections. Arch. Intern. Med. 148:1207-1210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roudier, C., M. Krause, J. Fierer, and D. G. Guiney. 1990. Correlation between the presence of sequences homologous to the vir region of Salmonella dublin plasmid pSDL2 and the virulence of twenty-two Salmonella serotypes in mice. Infect. Immun. 58:1180-1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roudier, C., J. Fierer, and D. G. Guiney. 1992. Characterization of translation termination mutations in the spv operon of the Salmonella virulence plasmid pSDL2. J. Bacteriol. 174:6418-6423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheehan, B. J., and C. J. Dorman. 1998. In vitro analysis of the interactions of the LysR-like regulator SpvR with the operator sequences of the spvA and spvR virulence genes of Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 30:91-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith, B. P., D. G. Oliver, P. Singh, G. Dilling, P. A. Marvin, B. P. Ram, L. S. Jang, N. Sharkov, J. S. Osborn, and K. Jackett. 1989. Detection of Salmonella dublin mammary gland infection in carrier cows, using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for antibody in milk or serum. Am. J. Vet. Res. 50:1352-1360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tezcan-Merdol, D., T. Nyman, V. Lindberg, F. Haag, F. Koch-Nolte, and M. Rhen. 2001. Actin is ADP-ribosylated by the Salmonella enterica virulence-associated protein SpvB. Mol. Microbiol. 39:606-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiss, S. H., M. J. Blaser, F. P. Paleologo, R. E. Black, A. C. McWhorter, M. A. Ashbery, G. P. Carter, R. A. Feldman, and D. J. Brenner. 1986. Occurrence and distribution of serotypes of the Arizona subgroup of Salmonella strains in the United States from 1967 to 1976. J. Clin. Microbiol. 23:1056-1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]