Abstract

The protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica is the causative agent of amoebiasis, a human disease characterized by dysentery and liver abscess. The physiopathology of hepatic lesions can be satisfactorily reproduced in the hamster animal model by the administration of trophozoites through the portal vein route. Hamsters were infected with radioactively labeled amoebas for analysis of liver abscess establishment and progression. The radioimaging of material from parasite origin and quantification of the number inflammation foci, with or without amoebas, described here provides the first detailed assessment of trophozoite survival and death during liver infection by E. histolytica. The massive death of trophozoites observed in the first hours postinfection correlates with the presence of a majority of inflammatory foci without parasites. A critical point for success of infection is reached after 12 h when the lowest number of trophozoites is observed. The process then enters a commitment phase during which parasites multiply and the size of the infection foci increases fast. The liver shows extensive areas of dead hepatocytes that are surrounded by a peripheral layer of parasites facing inflammatory cells leading to acute inflammation. Our results show that the host response promotes massive parasite death but also suggest also that this is a major contributor to the establishment of inflammation during development of liver abscess.

Amoebiasis is a widespread human parasitic disease caused by the protozoan Entamoeba histolytica. The two major clinical manifestations of E. histolytica infection are amoebic colitis and liver amoebic abscess. Yearly, 50 million people develop intestinal amoebiasis and it is estimated that 10% of individuals with amebic colitis will develop an amebic liver abscess. Amoeba infection causes 100,000 deaths per year, ranking, second after malaria, among the most deadly human parasitic diseases caused by a protozoan (6).

During invasive amoebiasis, highly motile trophozoites invade the intestinal epithelium, causing extensive tissue damage characterized by acute inflammation and ulceration with necrosis and hemorrhage. In contrast to intestinal amoebiasis, invasion of the liver is characterized by the presence of nonmotile E. histolytica trophozoites that cause an acute inflammatory reaction. Well-individualized infection foci contain mostly dead hepatocytes, polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN), macrophages, and parasites. Differences in pathology between amoebic colitis and amoebic liver abscess (ALA) likely result from a variation of the E. histolytica virulence repertoire in the two organs and from different responses of these organs to amoeba infection (11). Understanding the physiopathology of amoebiasis thus requires the development of new experimental strategies that take into account the multifactorial cross talk between the amoeba and the host cells during invasion of a specific human organ.

Our current knowledge of ALA development is essentially derived from studies with rodent models. Pioneer studies have shown that ALA formation after inoculation of E. histolytica into the portal vein of hamsters evolves through different phases (12). During the early stages, trophozoites brought by the bloodstream penetrate the liver sinusoids, where they are rapidly surrounded by host defense neutrophils, forming inflammatory foci. Trophozoites are separated from the hepatocytes by a ring of inflammatory cells. Hepatocytes show degenerative changes and lyse. During later stages, the infection foci acquire a characteristic organization with a central necrotic region composed of cellular debris surrounded by two peripheric layers, the first of trophozoites and the second of immune cells that separate the infection region from the hepatic tissue. Interestingly, direct contact of hepatocytes with trophozoites is observed only occasionally during infection, indicating that the hepatocytes’ massive death may be partially caused by diffusible products. It was hypothesized that such products originate from lysis of the neutrophils (12). The second rodent model that has been used for ALA development studies is severe combined immunodeficient mice (2), as well as normal mice or neutrophil-depleted mice (10, 13). The histological features of infected livers are similar to those found in the hamster. The death of hepatocytes and of cells of the immune system during E. histolytica invasion in these mice results not only from the cytolytic activity of the trophozoites but also from an apoptotic process (11). The not-yet-identified signaling pathway triggering apoptosis is independent of Fas-Fas ligand interactions and of the tumor necrosis factor alpha pathway (9).

We present here the first semiquantitative study of ALA development in hamsters. The fate of radioactively labeled trophozoites inoculated in the portal vein was monitored and quantified by histological analysis and radioimaging with a Beta-Imager. These sensitive procedures allowed us to detect quantitatively the amount of amoebic material in the liver and to determine its distribution in tissue sections. We estimated the survival and lysis rate of trophozoites reaching the liver after intraportal inoculation. The results show that a large number of trophozoites arriving in the liver die and that there is a critical early time point at which the success of infection is decided. The trophozoites that survive this early stage begin to multiply and cause significant tissue damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

E. histolytica cultivation and radioactive labeling.

Pathogenic E. histolytica strain HM1:IMSS was cultivated axenically in TYI-S-33 medium (4). Highly virulent trophozoites of strain HM1:IMSS (a gift of R. Perez Tamayo via Esther Orozco, CINVESTAV, Mexico City, Mexico) were passed through hamster livers every 2 months to maintain virulence.

Trophozoite cultures for intraportal inoculation were grown at 37°C for 48 h in closed bottles filled with medium. At 12 h before inoculation the trophozoites were diluted if required to ca. 50 to 60% saturation and 35S-protein labeling mix (NEN, Boston, Mass.) was added to 12 μCi/ml of medium. Radioactive labeling was carried out in complete TYI-S-33 medium because we observed that trophozoites were less fit and grew slower in medium lacking cysteine normally used to increase radioactivity incorporation. Before inoculation, the radioactive medium was decanted, and the adherent amoebas were washed twice with prewarmed medium before being detached by tapping the bottle and counted.

Hepatic inoculation procedure and preparation of infected liver sections.

Male Syrian golden hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus), aged 6 weeks, with an average weight of 100 g, were inoculated intraportally with 4 × 105 HM1:IMSS trophozoites. Treatment of animals and surgical procedures were done according to the method of Tsutsumi et al. (12). Groups of three animals were sacrificed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 h and at 1, 3, 5, and 7 days after inoculation. Control noninfested animals were sacrificed after 7 days. The livers were removed, inspected for the presence of amebic abscesses, and photographed. The infected livers were then treated for histological analysis and radioimaging analysis.

Quantitative determination of the radioactivity in liver sections.

The quantitative determination of the radioactivity in liver sections was carried out by using both a Micro-Imager and a Beta-Imager (Biospace, Paris, France) (3, 5). The radioimaging procedure converts the detected energy produced by ionized particles into light and intensifies the corresponding localized light spot observed by using a charge-coupled device camera (1). Data from digitized autoradiograms were collected for 8 to 14 h from five liver sections and three animals at each time point. The radioactivity was determined as the total counts per section.

Histology and immunohistochemistry.

Dissected livers were fixed in 10% buffered neutral formalin and embedded in paraffin. Serial 5-μm sections were stained with Harris' hematoxylin and periodic acid-Schiff reagent. Immunohistochemistry was performed on sections from different livers with a human polyclonal antibody to E. histolytica. The sections were deparaffinized and immersed in 200 μl of citrate buffer. They were then incubated with the human polyclonal antibody, washed three times in PBS, incubated with an anti-human immunoglobulin G, and visualized by the streptavidin-peroxidase method with aminoethyl carbazole as the chromogen.

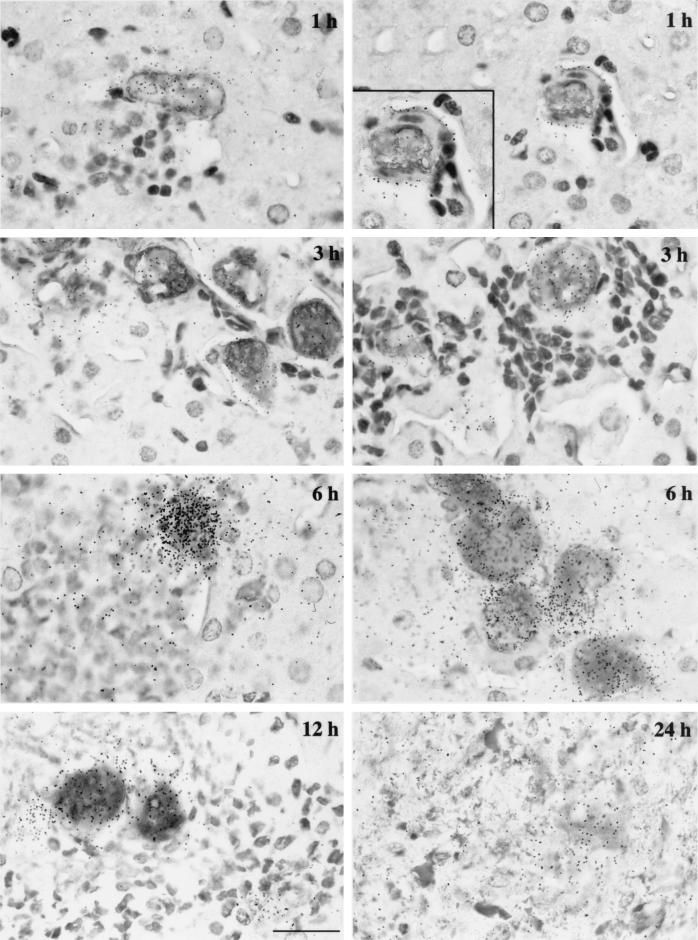

Tissue preparation for sectioning and light microautoradiographic visualization.

The localization of radioactive trophozoites was investigated by using the paraffin section autoradiography procedure (8). Serial 5-μm sections obtained from infected livers were used. The number of sections depended on the average size of inflammatory foci for each time point (see Results). Paraffin from these sections was removed with xylene, and slides were incubated through a descending and then an ascending ethanol series (from 100 to 50% [vol/vol] and then the reverse). Dried sections were processed for light microscope autoradiography by overloading a coverslip coated with a nuclear emulsion (Kodak NTB2, diluted 1:1 with distilled water). After the slides were air dried for 8 h at room temperature, they were exposed for 2 to 4 weeks in light-proof boxes at 4°C. Radiosensitive coverslips were developed for 3 min in Kodak D19 developer and fixed for 5 min in Kodak fixer. Sections were counterstained with Harris' hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted in Eukitt medium. The tissue and overlying silver grains were viewed and photographed with a Leica photomicroscope equipped with a bright-field optics (DMRD Leitz; Leica) camera.

RESULTS

Radioimaging examination of ALA development.

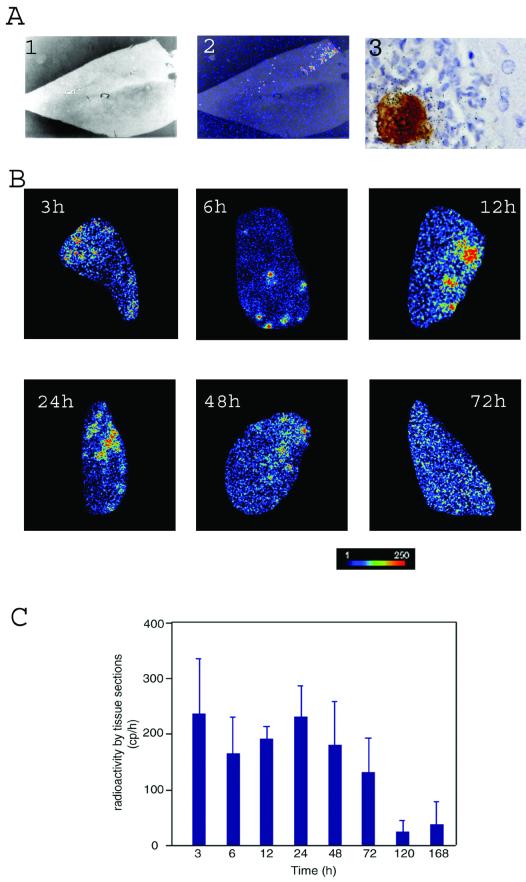

Intraportal infestation of young adult hamsters with trophozoites is a well-established method for reproducing the different stages of ALA formation. Parasites with 35S-labeled proteins were injected into the hamster portal vein. Sections of the infected liver were prepared from animals sacrificed at different times postinfestation ranging from 3 h to 7 days. The total radioactivity and its distribution in the complete tissue section were examined by using a Micro-Imager (Fig. 1). Fine detail was obtained by histological and immunological staining combined, when required, with detection of radioactivity emission by silver precipitation (Fig. 1A, panel 3). Radioactive material is strictly found in infected livers colocalizing with parasites or with ghosts of dead amoebas in a basically background-free environment. This method allows tracing the fate of the original trophozoites inoculated in the animal.

FIG. 1.

Radioimaging analysis of liver abscess formation. (A) Micrographs of dissected liver after 24 h of infection examined by Micro-Imager and histology: 1, optical acquisition (×10 magnification); 2, radiological acquisition of the same section, allowing localization of radioactive foci; and 3, radioimmunohistochemical photomicrograph, allowing the identification of E. histolytica (immunodetection), radioactive amoeba proteins (silver precipitation), and host cells (histological staining) (×1,000 magnification). (B) Distribution of 35S radioactivity in liver slices of animals infected with E. histolytica for the periods indicated in the micrographs. The radioactive material concentrates in discrete areas of the liver until 24 h, and then it exhibits a diffuse distribution before the signal becomes very weak after 72 h (results not shown). The bar under the panel indicates the intensity of the radioactivity by a colored scale from dark (no signal) to red (intense signal). (C) Radioactivity in total liver sections at several time points postinfection. Quantification made in the Beta-Imager is an average of the signal obtained during 1 h from five tissue sections from three different animals and for each time point. The surface of liver sections was of 250 mm2 ± 50 mm2. The bars represent the means plus the standard deviations of 15 determinations for each time point.

Visualization of amoeba radioactive material was also done by using the Beta-Imager. Analysis of complete tissue sections of infected liver showed strong individualized signals at 3 h postinfestation, indicating that parasites had reached the liver parenchyma at this early stage of the infection (Fig. 1B). As infection proceeds the pattern of focal radioactivity distribution is maintained for 24 h, but then it gets diffused throughout the complete section. The total amount of radioactivity in the tissue sections, however, decreases slowly until 3 days postinfestation (Fig. 1C). The data suggest that most of the original injected amoebas die or undergo cell division until 24 h postinfestation but that their radioactive proteins or breakdown products are mostly retained in the organ tissue until day 3. Radioactive products are then progressively eliminated from the liver by metabolism.

Kinetics of liver infiltrates in the presence of E. histolytica.

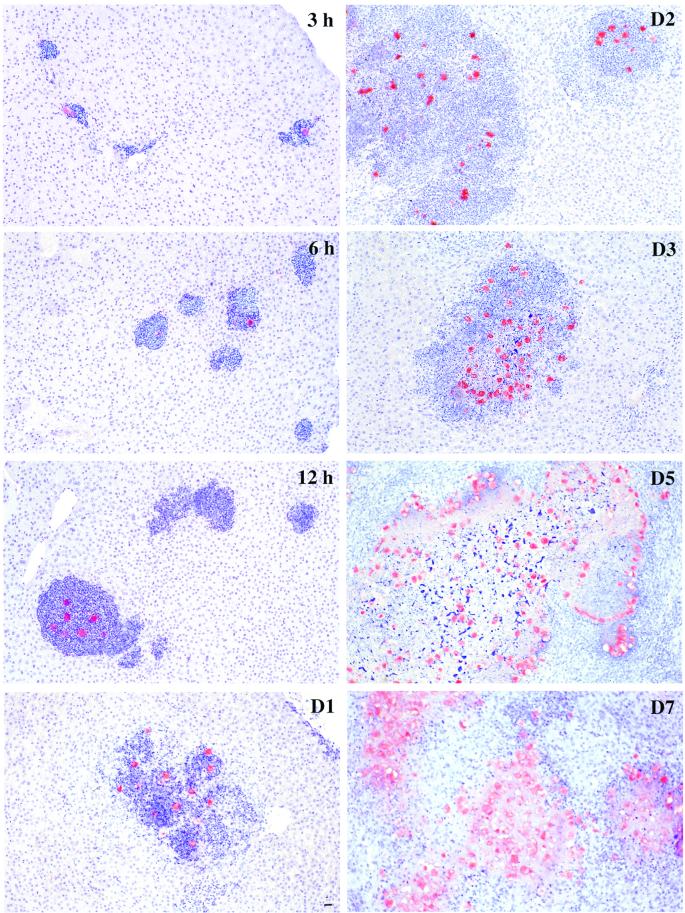

The indication that a significant number of original trophozoites reaching the liver do not survive, a feature of ALA not yet investigated, led us to analyze quantitatively their fate. The sequence of events occurring at the tissue level during ALA formation was monitored by histology (Fig. 2). The descriptive histology of disease development reproduces particularly well the seminal work of Tsutsumi et al. (12). Early stages of infection are characterized by acute cellular infiltration leading to irregular liver lesions ranging from 70 to 150 μm in diameter. Infectious foci present a large number of inflammatory cells surrounding normally a single parasite. In a significant number of cases no trophozoite is found in the inflammatory focus. At these early stages, parasites can be also seen in blood vessels surrounded by PMN, monocytes, and a few lymphocytes. The volume of infiltrates increases steadily as infection proceeds. Necrosis appears at 24 h and becomes obvious at 48 h. The hepatic lesions at this stage exhibit the characteristic features of ALA: the centers of the abscesses are filled with amorphous necrotic debris and edema, while viable amoebas form a peripheral layer that is surrounded by inflammatory cells delimiting the border between the area of necrosis and hepatic parenchyma (Fig. 2, days 3 to 7).

FIG. 2.

Histology of ALA progression. Sections of tissue liver from hamsters infected with E. histolytica for the periods indicated in the panels were stained with hematoxylin to visualize the hamster cells (in blue) and immunolabeled to visualize the trophozoites (in red). Note the presence of infiltrates containing PMN present already during the early stages of the infection. Several of these inflammatory foci appear without parasites. Infiltration is massive after 1 day postinfection, and necrosis is very well established at 2 days. Coalescent foci generate abscesses that show a central region of necrosis delimited by a ring of trophozoites surrounded by cells from the immune response, mainly PMN and macrophages. Bar, 20 μm.

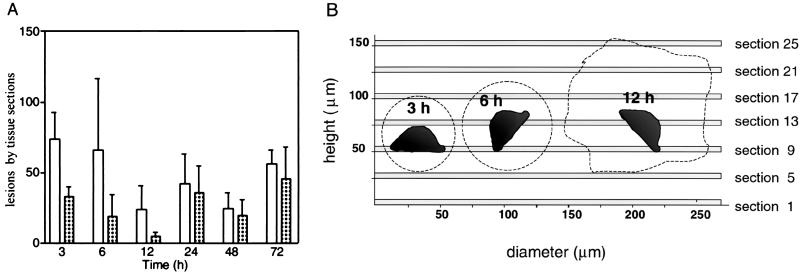

The highest number of inflammatory foci is found in the hamster liver during the early stages after intraportal inoculation of trophozoites (3 to 6 h), and this number decreases as ALA develops. A majority of the foci do not contain visible parasites (Fig. 3A). However, detection of radioactive material by silver precipitation in the histology sections demonstrated the presence of significant levels of radioactive protein of parasite origin in these foci (Fig. 4 and data not shown), originating most likely from dead trophozoites. We attribute the massive amoeba killing to the acute inflammatory response mediated by host immune system cells.

FIG. 3.

Quantitative analysis of inflammatory foci during development of ALA. (A) The total number of inflammatory foci (open bars) and foci with trophozoites (patterned bars) were counted in total liver sections processed as as described in Fig. 2. Values correspond to the average from counts of five tissue sections from three different animals for each time point indicated. The standard deviations are presented as a thin line at the top of each bar. No inflammatory foci were found in the liver sections of control animals that were not infected. (B) Serial sectioning experiment to quantify the total number of trophozoites per inflammatory foci. The 5-μm tissue sections stained for histology observation are presented as shaded bars, and the section number is on the right side. The average dimensions of inflammatory foci at 3, 6, and 12 h are drawn to scale (see text) as dashed lines whose shape provides an idea of the focus form. One trophozoite is schematized in the interior of each focus to illustrate its dimensions relative to the foci and to the tissue sectioning strategy.

FIG. 4.

Distribution of 35S-labeled material of trophozoite origin during ALA formation. E. histolytica was identified by immunolabeling, inflammatory cells were identified by staining, and radioactivity was visualized by using a radiosensitive emulsion. Strong precipitation of silver colocalizes with trophozoites, showing that radioactive material is brought in by amoebas. At early stages, silver grains are deposited on the surface of endothelial cells (magnification view at 1 h). While infiltration develops, radioactive debris can be found in numerous inflammatory foci associated in a number of cases with discernible ghosts of dead amoebas. The ghosts are characterized by a diffuse antiamoeba antibody staining that overlaps with the silver grain concentration; this can be seen on the micrograph illustrating the 24-h infection silver grain concentration. Bar, 20 μm.

Histological observations suggest that an important number of inflammatory foci do not contain parasites. A quantitative assessment of the number of inflammatory foci with or without intact trophozoites requires a statistically representative counting and serial sectioning of the foci to check at different planes whether amoebas are present. A preliminary single-section analysis was used to determine the average diameter of inflammatory foci for each time point of the infestation kinetics. Visual inspection confirmed that inflammatory foci without trophozoites are normally observed at 3, 6, and 12 h postinfection (Fig. 2). We then made serial sections of 5 μm that span >130% of the average height of the foci for these three time points and also for 24 h. Sections spaced by 20 μm (the average diameter of a trophozoite is 25 μm) were prepared for histology staining (Fig. 3B). Observation of serial histology sections provided a three-dimensional view of the inflammatory foci at a resolution at which the presence of trophozoites can be detected accurately. The study was only continued for the time points 3, 6, and 12 h because the vast majority of foci contained at least one trophozoite at 24 h postinfection, as was already suspected from single-section observation (Fig. 2; data not shown). The foci had a regular spherical or oval three-dimensional shape at 3 and 6 h postinfection, whereas they exhibited a more irregular form with lobular protuberances after 12 h. The total number of foci without trophozoites (referred to as “negative” here) and with one or more trophozoites (“positive”) that were present in each serial section was scored first. Second, foci that were negative in one section were examined by inspection of serial sections along their complete height. In this way, the percentage of negative foci in one section that contained a parasite at a different plane of the inflammatory focus was estimated. Starting from a central section in the series (e.g., section 9 for 3 and 6 h; Fig. 3B) and from negative foci in that section, we analyzed 30 complete foci for 3 h postinfection: 31 for 6 h and 26 for 12 h. Among these 20, 29, and 4% were found to contain one or more trophozoites for the time points 3, 6, and 12 h, respectively. These percentages were used as correction factors for the average counts of individual serial sections (Table 1). The results with these corrected data agree well with those from Fig. 3A and demonstrate the validity of quantifications based on tissue section inspection.

TABLE 1.

Quantitative determination of the number of inflammatory foci without trophozoites, with one trophozoite, or with more than one trophozoite at 3, 6, and 12 h postinfectiona

| Time point (h) | Avg focus diam in μm ± SD (n) | Ht (μm) covered by serial cutting | Foci per tissue section

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of foci | Foci without amoebas (%) | Foci with:

|

|||||

| 1 amoeba (%)* | ≥2 amoebas (%) | Total (%)* | |||||

| 3 | 70.8 ± 18.3 (98) | 105 | 101 | 44 | 46 | 10 | 56 |

| 6 | 78.8 ± 18.6 (85) | 105 | 79 | 51 | 39 | 10 | 49 |

| 12 | 122.9 ± 21.3 (35) | 225 | 73 | 86 | 6 | 8 | 14 |

| 24 | 459.8 ± 132.1 (45) | 600 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

The details of this experiment are described in the text. The average diameter of the inflammatory foci measured at different times postinfection in tissue sections is shown in column 2, and the number of serial sections made to scan the complete height of foci at each time point is shown in column 3. n = number of scored foci. The total number of foci analyzed in serial sections (column 4) was then divided according to the finding of no trophozoites, one trophozoite, or more than one trophozoite. The results in the right columns are presented as the percentage of the total number of foci. To calculate the values presented, we applied a correction factor (*) to the number of foci without amoebas that takes into consideration the percentage of cases in which a negative focus becomes positive when its complete height is analyzed in the serial sections [i.e., the percent foci without amoebas = 100 × (the total counts of foci without amoebas) − (the total counts of foci without amoebas) × (the correction factor)/the total number of foci]. A correction factor was calculated for each experimental time point (see the text). The percentage of foci with amoebas was then corrected based on the calculated percentage of foci without amoebas.

In the early stages after intraportal inoculation of trophozoites (3 to 6 h), 40 to 60% of the inflammatory foci in the hamster liver do not contain visible parasites (Fig. 3A and Table 1). The success of liver abscess establishment has a commitment step at 12 h postinfestation. A minimum number of foci are reached at this time point, and only ∼10% of these contained live trophozoites that certainly account for the success of ALA development (Fig. 3A and Table 1). Later, the number of infection foci increases, and the majority of them contain more than one live amoeba, indicating that trophozoite cell division has resumed, and therefore the size of the lesion increases (Fig. 2, 3, and 4 and data not shown). Well-organized infectious foci can be counted up to 3 days, after which they start to coalesce until the formation of uniform necrotic areas.

Quantification of infectious foci with 35S-labeled trophozoites.

The fate of trophozoites and of their 35S-labeled proteins was examined by immunolabeling and silver precipitation. Parasites revealed by an antiamoebic antibody were labeled specifically with radioactivity (Fig. 4). At the early stages, during which the amoeba invades the liver, radioactivity is often encountered on the surface of endothelial cells (Fig. 4, 1 h, left and right panels). The radioactive ghosts of dead amoebas and/or debris can then be found in numerous inflammatory foci. Ghosts are characterized by diffuse antibody staining that overlaps with silver grains (Fig. 4, e.g., 3 and 12 h). Detection of radioactive material by silver precipitation in the histology sections demonstrated the presence of significant levels of radioactive protein of parasite origin in these foci (Fig. 4 and data not shown), originating most likely from dead trophozoites. We attribute the massive amoeba killing to the acute inflammatory response mediated by host immune system cells. This observation reconciles the constant level of radioactivity detected in complete liver sections (Fig. 1C) with the very significant variations observed in inflammatory foci and amoeba counts during the first days postinfestation (Fig. 3A and Table 1). At advanced stages of ALA, labeling is found in the central necrotic area of the lesion (Fig. 4, 24 h). Silver spots are also detected in the hepatic tissue close to regions with amoebas. These are attributed to products left behind during amoeba motion or to proteins secreted by the trophozoites after their arrival in the liver that may promote tissue destruction.

DISCUSSION

Liver invasion by E. histolytica with production of abscesses is the most common extraintestinal manifestation of amoebiasis. Infection with radioactive parasites of immunocompetent hamsters by the intraportal route allowed a description of abscess development by radioimaging combined with histological analyses. Our study shows that E. histolytica infection of the liver has a fast temporal program in which the parasite crosses the endothelium of liver sinusoids, disseminates through the organ, and adapts to the new environment before it starts to divide and establish itself successfully to cause massive organ damage. An important finding was that parasites are largely destroyed by the native immune system; we determined that the period between 6 and 12 h is critical for amoeba survival and subsequent ALA development.

In the hamster model system the parasites reach the liver in the bloodstream through the portal vein. During early stages of ALA development, amoebic radiolabeled material is deposited on the surface of endothelial cells (Fig. 4), suggesting that these cells are rapidly attacked by elements of the cytotoxic system of parasites. This might be the initial trigger for the inflammatory response. It was found that in humans suffering from amoebiasis the liver endothelial cells secrete proinflammatory factors after contact with E. histolytica (14). The proinflammatory factors lead to recruitment and activation of immune cells that are responsible for the killing of parasites at early stages postinfection. Our preliminary results indicate that endothelial cells of the hamster sinusoids undergo apoptosis in the presence of trophozoites (unpublished results). The resulting disturbance of the endothelial barrier likely facilitates the passage of trophozoites between the blood circulation and the hepatic tissue.

The variation in numbers and redistribution of trophozoites and host immune cells in the first 24 h of ALA development demonstrate a highly dynamic interaction between these different cells. Inflammatory cells are rapidly recruited after the arrival of parasites to the liver, forming large foci around the trophozoites and eliminating the majority of them. Consequently, most of the foci do not contain a live amoeba after 12 h of infestation (Fig. 3). Among the cells of the immune system, neutrophils probably play the central role in the elimination of E. histolytica since parasite debris are normally surrounded by neutrophils in the hamster animal model (Fig. 2 and 4), and liver lesions are more prominent in neutrophil-depleted mice than in normal mice (10, 13).

After the initial killing of trophozoites that leads to a significant reduction of positive foci, there is an increase of at least sixfold in the number of foci with amoebas between 12 and 24 h postinfection. This is due to the multiplication of survivor trophozoites (at 12 h postinfection the few positive foci detected have more than one amoeba in numerous cases [Fig. 3 and Table 1]) and to their migration in the liver tissue to positions where new inflammatory foci are formed. Trophozoites leaving the foci or localized in their periphery can be easily observed in histology sections of infected livers (Fig. 2). The significant variations in the numbers of positive and negative foci during the first 24 h of ALA development (Fig. 3) reflect a very dynamic movement of both parasites and cells of the immune system in the infected hamster liver.

The results presented here show that E. histolytica trophozoites that were grown under axenic conditions and injected via the portal route are susceptible to the immunoresponse upon their arrival into the liver. After 12 h of infection the trophozoites multiply and the immune system is not able to oppose the fast dissemination of the parasite. It is possible that the adaptation of trophozoites to the liver environment requires the expression of a repertoire of genes necessary for survival and for escape from the immune system. Evidence suggesting that complement resistance has to be acquired by E. histolytica to survive during invasion of the human liver has been reported, for example, by Reed et al. and Walderich et al. (7, 15). There is therefore a commitment phase necessary for ALA development that relies on the presence of well-adapted survivor trophozoites. A most interesting question is whether, during amoebiasis, the trophozoites that cross the intestinal parenchyma and enter the blood circulation, which is the normal route for reaching the liver, are ready to colonize the liver or whether they have to undergo the same adaptation discussed above. Regardless of this issue, the hamster experimental model of amoebiasis provides a very valuable system for identifying the requirements for E. histolytica pathogenesis and for investigating the molecular basis for how the parasite adapts its genetic program depending on the tissue environment. Understanding this program will pave the way for the identification of major parasite factors that account for the aggressive behavior of E. histolytica at different stages of amoebiasis.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Perez-Tamayo and E. Orozco for kindly providing us with the indispensable E. histolytica strain for the realization of these experiments. We also acknowledge I. Fernandez for discussions, M. Mavris for manuscript advice, and P. Sansonetti for continuous support and interest in the project.

This work was supported by grants from the French Ministry of National Education through the PRFMMIP program. P.T. was supported by EMBO and FCT postdoctoral fellowships.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Charpak, G., W. Dominik, and N. Zaganidis. 1989. Optical imaging of the spatial distribution of beta-particles emerging from surfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:1741-1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cieslak, P. R., H. W. Virgin, and S. L. Stanley. 1992. A severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mouse model for infection with Entamoeba histolytica. J. Exp. Med. 176:1605-1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crumeyrolle-Arias, M., M. Jafarian-Tehrani, A. Cardona, L. Edelman, P. Roux, P. Laniece, Y. Charon, and F. Haour. 1996. Radioimagers as an alternative to film autoradiography for in situ quantitative analysis of 125I-ligand receptor binding and pharmacological studies. Histochem. J. 28:801-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diamond, L. S., D. R. Harlow, and C. C. Cunnick. 1978. A new medium for the axenic cultivation of Entamoeba histolytica and other Entamoeba. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 72:431-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laniece, P., Y. Charon, A. Cardona, L. Pinot, S. Maitrejean, R. Mastrippolito, B. Sandkamp, and L. Valentin. 1998. A new high resolution radio-imager for the quantitative analysis of radio-labelled molecules in tissue section. J. Neurosci. Methods 86:1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ravdin, J. I. 1995. Amebiasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20:1453-1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reed, S. L., J. G. Curd, I. Gigli, F. D. Gillin, and A. I. Braude. 1986. Activation of complement by pathogenic and nonpathogenic Entamoeba histolytica. J. Immunol. 136:2265-2270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rougeot, C., R. Vienet, A. Cardona, L. Le Doledec, J. M. Grognet, and F. Rougeon. 1997. Targets for SMR1-pentapeptide suggest a link between the circulating peptide and mineral transport. Am. J. Physiol. 273:1309-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seydel, K. B., and S. L. Stanley. 1998. Entamoeba histolytica induces host cell death in amebic liver abscess by a non-Fas-dependent, non-tumor necrosis factor alpha-dependent pathway of apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 66:2980-2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seydel, K. B., T. Zhang, and S. L. Stanley. 1997. Neutrophils play a critical role in early resistance to amebic liver abscesses in severe immunodeficient mice. Infect. Immun. 65:3951-3953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanley, S. L. 2001. Pathophysiology of amebiasis. Trends Parasitol. 17:280-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsutsumi, V., R. Mena-Lopez, F. Anaya-Velazquez, and A. Martinez-Palomo. 1984. Cellular bases of experimental amebic liver abscess formation. Am. J. Parasitol. 117:81-91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Velazquez, C., M. Shibayama-Salas, J. Aguirre-Garcia, V. Tsutsumi, and J. Calderon. 1998. Role of neutrophils in innate resistance to Entamoeba histolytica liver infection in mice. Parasite Immunol. 20:255-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ventura-Juarez, J., R. Campos-Rodriguez, H. A. Rodriguez-Martinez, A. Rodriguez-Reyes, A. Martinez-Palomo, and V. Tsutsumi. 1997. Human amebic liver abscess: expression of cellular adhesion molecules 1 and 2 and of von Willebrand factor in endothelial cells. Parasitol. Res. 83:510-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walderich, B., A. Weber, and J. Knobloch. 1997. Sensitivity of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar patient isolates to human complement. Parasite Immunol. 19:265-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]