Abstract

Application of antigens with an adjuvant onto bare skin is a needle-free and pain-free immunization procedure that delivers antigens to the immunocompetent cells of the epidermis. We tested here the immunogenicity and adjuvanticity of two mutants of heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) of Escherichia coli, LTK63 and LTR72. Both mutants were shown to be immunogenic, inducing serum and mucosal antibody responses. The application of LTK63 and LTR72 to bare skin induced significant protection against intraperitoneal challenge with a lethal dose of LT. In addition, both LT mutants enhanced the capacity of peptides TT:830-843 and HA:307-319 (representing T-helper epitopes from tetanus toxin and influenza virus hemagglutinin, respectively) to elicit antigen-specific CD4+ T cells after coapplication onto bare skin. However, only mutant LTR72 was capable of stimulating the secretion of high levels of gamma interferon. These findings demonstrate that successful skin immunization protocols require the selection of the right adjuvant in order to induce the appropriate type of antigen-specific immune responses in a selective and reliable way. Moreover, the use of adjuvants such the LTK63 and LTR72 mutants, with no or low residual toxicity, holds a lot of promise for the future application of vaccines to the bare skin of humans.

Recently, bare skin has emerged as a potential alternative route for vaccine delivery (11, 27). This is because the skin is rich in immunocompetent cells (4, 36), and when antigens are applied with a suitable adjuvant either in solution (1, 11, 13, 34) or with a patch (14), they induce potent immune responses. The development of noninvasive immunization procedures, which can be needle free and pain free, is a top priority for public health agencies. This is because many current immunization practices are unsafe, particularly in developing countries due to the widespread reuse of nonsterile syringes (27). Therefore, the topical application of vaccines is attractive since it has the potential to make vaccine delivery more equitable, safer, and efficient. Furthermore, it would greatly facilitate the successful implementation of worldwide mass vaccination campaigns against infectious diseases.

For the induction of an effective immune response, the antigen is normally coapplied onto hydrated bare skin with an ADP-ribosylating exotoxin as an adjuvant (i.e., Vibrio cholerae cholera toxin [CT] or Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin [LT]) (1, 11, 13, 34). Both CT and LT are composed of five nontoxic B subunits held together in a pentamer (responsible for binding to the cell membrane), surrounding a single A subunit, which is responsible for toxicity. The A subunit consists of two distinct structural domains: the A1 domain, which displays the ADP-ribosyltransferase activity in the cytosol of the target cells and the A2 domain that interacts with the B-subunit (35). These toxins are responsible for the cause of a debilitating watery diarrhea (35). Moreover, they are potent immunogens and exert an adjuvant effect on antigens presented simultaneously at the mucosal surfaces (26). When CT and LT are applied to bare skin it appears that they are well tolerated even at a high dose without any apparent sign of local or systemic toxicity (14). However, it is obvious that there would be some serious concerns for their use in humans. This has prompted researchers to genetically detoxify these toxins while retaining their adjuvanticity. By site-directed mutagenesis, several mutants have been generated with significantly reduced ADP-ribosylating activity and toxicity compared to the holotoxin (5, 6, 20, 30, 37). Two of these mutants, LTK63, which is devoid of enzymatic activity and toxicity (containing a serine-to-lysine substitution in position 63 of the A subunit), and LTR72, which retains ca. 1% of the wild-type ADP-ribosylating activity and reduced toxicity (containing an alanine-to-arginine substitution in position 72 of the A subunit), have been extensively tested and shown to be good adjuvants after mucosal coadministration with protein and peptide antigens (24, 29). Furthermore, these mutants have been shown to be very useful tools for examining the role of ADP-ribosylation in immunomodulation (32).

Since the LTK63 and LTR72 mutants are promising candidates for human use (28), we hypothesized that their use might allow us to circumvent the potential hazards of LT and CT after topical application. Therefore, we sought to investigate their immunogenicity and to test their adjuvanticity to peptide antigens after their coapplication to bare skin. Both mutants were shown to be effective immunogens, conferring protection against challenge with LT and enhancing the capacity of coadministered peptides to induce antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. In addition, the LTR72 mutant was shown to stimulate the secretion of high levels of gamma interferon (IFN-γ).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthetic peptides.

The synthetic peptides TT:830-843 [QYIKANSKFIGITE(C)] and HA:307-319 [PKYVKQNTLKLAT(C)] representing promiscuous (non-major histocompatibility complex-restricted) T-helper epitopes from tetanus toxin (7) and influenza virus hemagglutinin (25), respectively, were synthesized by using Fmoc (9-fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl) chemistry. The influenza virus NP:55-69 (RLIQNSLTIERMVLS) peptide representing a T-helper epitope from nucleoprotein was synthesized by using the same chemistry and was tested as a control peptide. After cleavage, the peptides were purified by preparative high-performance liquid chromatography and then characterized by analytical high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectroscopy.

Mice.

Female BALB/c mice, 6 to 8 weeks old at the start of the experiments, were purchased from Harlan (Gannat, France) and were maintained in the animal facility of the Institut de Biologie Moléculaire et Cellulaire, Strasbourg, France.

Immunizations.

Prior to immunization, mice were shaved on a restricted area of the abdomen (over an ca. 1- to 2-cm2 surface area). During the immunization procedure the mice were under deep anesthesia after subcutaneous injection of 100 μl of solution of ketamine (Imalgene 1000 [15%]; Merial, Lyon, France) with xylasine (2% Rompun [9%]; Bayer AG, Leverkusen, Germany) for ca. 1 h to prevent grooming. Groups of BALB/c mice were immunized onto bare skin with a 30-μl volume of antigen solution (i) as a solution of 100 μg of TT:830-843 peptide with 50 μg of LT (Sigma) (eight mice), (ii) as a solution of 100 μg of TT:830-843 peptide with 50 μg of LTK63 (six mice), (iii) as a solution of 100 μg of TT:830-843 peptide with 50 μg of LTR72 (six mice), or (iv) as a solution of 100 μg of TT:830-843 peptide given in saline (two mice). At 2 weeks after priming, the mice were boosted by the same route with the same dose and formulation of antigen. In a separate experiment, the adjuvanticity of 50 μg of each of LT mutants was tested after coapplication with 100 μg of HA:307-319 peptide onto bare skin of BALB/c mice (two mice/group). Control mice were immunized with a mixture of 50 μg of CT and 100 μg of synthetic oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN) containing the CpG motif 1668 (5′-TCC ATG ACG TTC CTG ATG CT-3′) (18), purchased from MWG Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany. A booster application was given 14 days postpriming. No erythema was observed after the shaving or during and after the immunization procedure.

LT challenge.

Groups of BALB/c mice were immunized onto bare skin with 50 μg of LTR72 (10 mice) or LTK63 (5 mice) mutant on days 0 and 14. Three weeks after the boost, immune mice and 11 nonimmune mice were challenged intraperitoneally with 50 μg (a 2.5 50% lethal dose) of recombinant LT in sterile saline (200 μl/mouse). After challenge, mice were monitored daily for morbidity and mortality.

Collection of vagina washes.

Vagina washes were collected by gentle pipetting of 30 μl of sterile saline containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) into and out the vagina lumen several times, followed by collection of the effluent. To limit the effect of estrous cycle on local antibody responses, vagina washes from two consecutive days were collected, pooled, centrifuged to remove particulate matter, and stored at −20°C until testing.

Measurement of antibody responses.

Antibodies were measured by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Briefly, 96-well microtiter plates (Falcon, Oxnard, Calif.) were coated overnight with 5 μg of LT/ml in 0.05 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) at 37°C. The plates were blocked with 1% BSA in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) at 37°C for 2 h. After the plates were washed with PBS-T, serial twofold dilutions of serum or vaginal washes in PBS-T containing 0.25% BSA were made across the plate (final volume, 50 μl), and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. At the end of the incubation period, the plates were washed with PBS-T and incubated with 50 μl of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG; 1/20,000; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, Pa.), anti-mouse IgA (1/5,000), or the anti-mouse IgG subclasses IgG1 and IgG2a (1/10,000 for IgG1 and IgG2a; Nordic Immunology, Tilburg, The Netherlands)/well that was Fc specific for 1 h at 37°C. Unbound conjugate was removed by washing the mixtures with PBS-T, and the enzymatic activity was determined as previously described (1). Data are expressed as antibody titers (log10) corresponding to the reciprocal dilution giving an absorbance of 0.2 at 450 nm. Levels of total IgE antibodies in serum (serum samples were tested at a 1/20 dilution) were measured by a double-sandwich-based ELISA kit (OptEIA Set, mouse IgE; PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Assay for proliferative T-cell responses.

Spleens were aseptically removed, and a single cell suspension was prepared in RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies, Cergy-Pontoise, France) supplemented with 100 IU of gentamicin/ml, 2 mM l-glutamine, 25 mM HEPES, and 1% heat-inactivated autologous mouse serum 2 weeks after the booster application of antigen formulation onto bare skin. A total of 4 × 105 viable splenocytes was cultured in 0.2-ml volumes in the presence of various concentrations of antigens. Supernatants collected after 72 h of culture were tested for their ability to support the proliferation of the interleukin-2 (IL-2)-dependent cell line CTLL-2 (9) after the culture of 105 cells/ml for 31 h. Then, 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine was added 7 h before the end of the culture, and incorporation was measured with a Matrix 9600 Direct Beta counter (Packard, Downers Grove, Ill.). A standard curve performed with known concentrations of recombinant mouse IL-2 (0 to 45 U/ml; PharMingen) was used as an internal control to calculate the concentration of secreted IL-2.

Purification of CD4+ T cells.

CD4+ T cells were separated from pooled splenocytes by using a magnetic cell separation device (MPC-6; Dynal, Oslo, Norway), Dynabead M-450 rat anti-mouse CD4+ monoclonal antibody (Dynal), and DETACHaBEAD according to a well-established laboratory protocol (21) and the manufacturer's instructions. The purity of the positively selected CD4+ T cells was assessed by flow cytometry with a rat anti-mouse CD4+ monoclonal antibody (L3T4) (PharMingen) and the corresponding fluorescent monoclonal immunoglobulin isotype standard. Tested CD4+ T cells were >90% pure (data not shown). Purified CD4+ T cells (5 × 105 per well) were cultured in 96-well plates in the presence or absence of mitomycin-treated splenocytes as APCs (105 per well). For mitomycin treatment, 5 × 107 splenocytes (in 1 ml of PBS) were mixed with 100 μl of mitomycin C (Sigma; 500 μg/ml in PBS). After incubation at 37°C for 20 min, cells were washed three times in RPMI 1640 medium before use. Prior to coculture, APCs were incubated with different concentrations of peptide for 1 h at 37°C. Supernatants collected after 72 h of culture were tested for IL-2 secretion as described above.

IFN-γ ELISA assay.

Levels of IFN-γ in culture supernatants collected after 72 h of culture of pooled splenocytes in the presence of antigen were measured by a double-sandwich ELISA with commercial antibodies from PharMingen. Briefly, polyvinyl Falcon plates were coated overnight at 4°C with 50 μl of 1 μg of purified rat anti-mouse IFN-γ (clone R4-6A2)/ml as the capture antibody in carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6). After being washed with PBS-T, the plates were blocked with 1% BSA and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. After the plates were washed with PBS-T, the supernatants were added in triplicate, and the plates were incubated at room temperature for 4 h. At the end of the incubation, the plates were washed, and 100 μl of a matched biotinylated rat anti-mouse IFN-γ (XMG1.2) monoclonal antibody (1 mg/ml) was added to each well. The plates were further incubated at room temperature for 1 h and then washed with PBS-T; avidin conjugated to peroxidase was then added to each well at room temperature for 30 min. The remaining steps of the assay were performed as described above (see the section on the measurement of antibody responses). The results are expressed as mean IFN-γ concentrations ± the standard deviation (SD), after extrapolation from a standard curve prepared with standard cytokine for each antigen concentration tested in duplicate.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed by using the two-tailed Student's t test. Comparisons of survival rates after LT challenge were made by using the Kaplan-Meier product-limit method and analysis by the log rank test. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Immunogenicity of LT mutants after application onto bare skin.

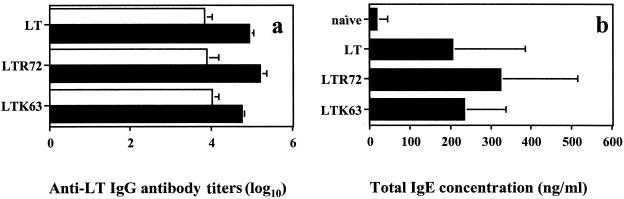

Figure 1a shows that both LT mutants elicited primary and secondary serum antibody responses. However, the mutant LTR72 was significantly more immunogenic than LTK63 after the boost (P = 0.0002). When antibody responses were compared to those induced by LT, the LTR72 mutant elicited significantly higher antibody titers (P = 0.024), whereas the LTK63 elicited significantly lower titers (P = 0.005) (Fig. 1a). The predominant IgG subclass after the boost was IgG1, with the ratios of IgG1 to IgG2a ranging from 2.02 for LT (IgG1 titer, 4.92 ± 0.12; IgG2a titer, 2.43 ± 0.46), 1.89 for LTK63 (IgG1 titer, 4.44 ± 0.07; IgG2a titer, 2.35 ± 0.61), and 2.5 for LTR72 (IgG1 titer, 4.54 ± 0.15; IgG2a titer, 1.81 ± 0.36). Both mutants induced detectable levels of IgG (average titers of 4.21 ± 0.17 and 2.61 ± 0.17 for LTR72 and LTK63, respectively) and IgA (average titers of 3.6 ± 0.16 and 2.4 ± 0.18 for LTR72 and LTK63, respectively) antibodies in vaginal washes, with mutant LTR72 being more immunogenic. The total IgE levels in serum were significantly elevated compared to those of naive mice (P = 0.0001, P = 0.0008, and P = 0.013 for LTK63, LTR72, and LT, respectively) (Fig. 1b). However, no significant difference was observed between the two mutants (P = 0.335).

FIG. 1.

Levels of anti-LT IgG (a) and total IgE antibodies (b) in serum. Mice were coimmunized onto bare skin with 100 μg of TT:830-843 peptide and 50 μg of LTK63 or with 50 μg of LTR72 mutant or 50 μg of LT as an adjuvant on days 0 and 14. Figure 1a presents the mean antibody titers ± the SD of groups of mice bled on days 14 (□) and 28 (▪) after priming. Panel b presents the average concentrations of total IgE levels ± the SD in serum from groups of mice bled on day 28 after priming.

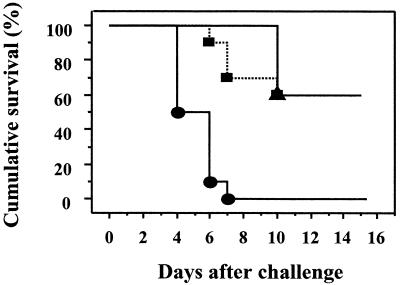

Protection against lethal LT challenge.

To test the potential of skin immunization for the induction of protective immune responses, groups of BALB/c mice immunized with LT mutants onto bare skin were challenged via the intraperitoneal route with a lethal dose of LT. All immunized mice seroconverted prior to toxin challenge (mean antibody titers of 4.94 ± 0.19 and 4.58 ± 1.65 for LTR72 and LTK63, respectively, at 2 weeks before LT challenge). After intraperitoneal challenge with LT, immune mice were significantly protected (P = 0.0001 for LTR72 and P = 0.004 for LTK63) compared to the control nonimmune mice (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Percent survival after intraperitoneal challenge with a lethal dose of recombinant LT (50 μg) of groups of BALB/c mice bare-skin immunized with LTR72 (n = 10, ▪) or LTK63 (n = 5, ▴). Also shown are data for control nonimmune mice (n = 11, •).

Mutants LTK63 and LTR72 enhance the capacity of TT:830-843 peptide to elicit CD4+ T cells.

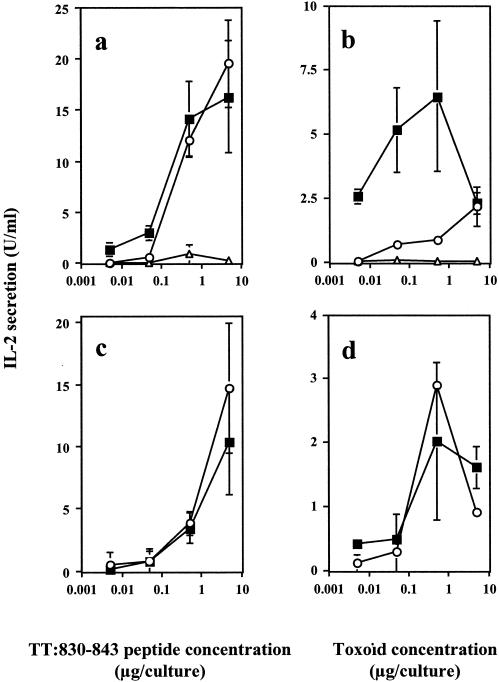

To determine whether the LT mutants can act as adjuvants, groups of mice were coimmunized with peptide TT:830-843 and LTK63 or LTR72 onto bare skin. Control mice were immunized by topically applying peptide TT:830-843 in saline or peptide TT:830-843 with LT. As shown in Fig. 3a, splenocyte cultures of mice immunized with peptide and LT mutants secreted significantly higher IL-2 levels upon in vitro restimulation with the homologous peptide compared to those of mice immunized with peptide alone (P = 0.0001). The levels of IL-2 secretion in culture supernatants of mice coimmunized with peptide TT:830-843 and LT were 22.5 ± 1.5, 17.85 ± 1.6, and 2.9 ± 1.75 U/ml in the presence of 5, 0.5, and 0.005 μg of homologous peptide/culture, respectively. Recall responses were also measured upon in vitro restimulation of splenocytes with tetanus toxoid (TTx) in groups of mice coimmunized topically with peptide and LT mutants but not in those immunized with the peptide in saline (Fig. 3b) or with LT (data not shown). These responses were dose dependent and significantly higher in splenocyte cultures of mice immunized with LTR72 (P = 0.023, P = 0.0136, and P = 0.0007 in the presence of 0.5, 0.05, and 0.005 μg of TTx/culture, respectively). No IL-2 secretion was measured upon in vitro restimulation with control peptide NP:55-69 (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Secretion of IL-2 by splenocytes (a and b) or purified CD4+ splenocyte T cells (c and d) of mice coimmunized onto bare skin with 100 μg of TT:830-843 peptide plus 50 μg of LTK63 (○) or with 50 μg of LTR72 (▪). Control mice were immunized with 100 μg of TT:830-843 peptide given alone (▵). Splenocyte cultures or mitomycin-treated splenocyte APCs were restimulated in vitro or pulsed with various concentrations of TT:830-843 peptide (a and c) or TTx (b and d), and supernatants collected after 72 h of culture were tested for IL-2 secretion with the CTLL-2 IL-2-dependent cell line. Data are presented as IL-2 units/milliliter from hexaplicate cultures in the presence of peptide or TTx (triplicate cultures) ± the SD.

To assess the phenotype of proliferating T cells, CD4+ cells were isolated with a magnetic cell separation device and cocultured with mitomycin-treated splenocytes pulsed with antigen. As shown in Fig. 3c, purified CD4+ T cells of mice coimmunized with peptide TT:830-843, plus LTK63 or LTR72, secreted IL-2 in the presence of various concentrations of homologous peptide. Levels of IL-2 secretion in the culture supernatants of mice coimmunized with peptide TT:830-843 and LT were 24.65 ± 1.75 and 3.65 ± 0.9 U/ml in the presence of 5 and 0.5 μg of TT:830-843 peptide/culture, respectively. Recall proliferative responses were also measured after in vitro restimulation with various concentrations of TTx (Fig. 3d). After skin immunization, low levels of IL-2 secretion were also detected in the culture supernatants of inguinal lymph nodes restimulated with peptide but not with TTx (data not shown). Although peptide TT:830-843 induced proliferative T-cell responses, it did not elicit any detectable antibody responses (data not shown). This suggests that the peptide does not contain any B-cell epitope(s).

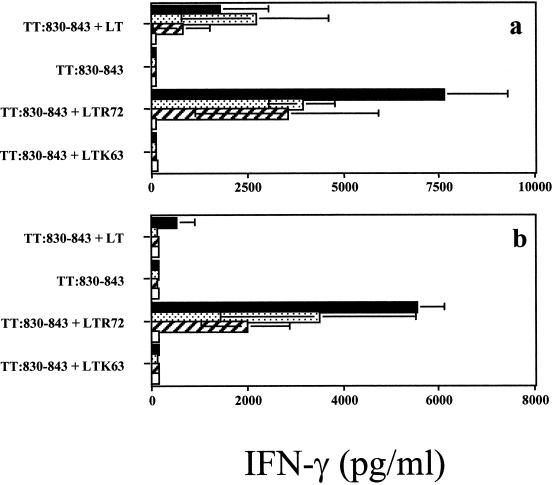

The secretion of IFN-γ is the hallmark feature of the Th1-type response that contributes to the clearance of viral infections and of other intracellular pathogens. Therefore, the IFN-γ response of immunized mice was measured in the supernatants of splenocyte cultures by ELISA. Mice immunized with TT:830-843 peptide plus LTR72 gave a strong IFN-γ response in the presence of homologous peptide or TTx (Fig. 4). In contrast, IFN-γ was not detectable in the supernatants of splenocyte cultures of mice immunized with peptide in saline or with LTK63 mutant (Fig. 4). Splenocyte cultures of mice immunized with peptide TT:830-841 plus LT secreted IFN-γ in the presence of homologous peptide but not with TTx (Fig. 4). Restimulation of splenocyte cultures with control peptide NP:55-69 did not produce any IFN-γ (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Secretion of IFN-γ by TT:830-843 peptide-specific immune splenocytes after in vitro restimulation with various concentrations of the homologous peptide (a) or TTx (b) (▪, 0.5 μg/culture; , 0.05 μg/culture; and ▨, 0.005 μg/culture). Mice were coimmunized onto bare skin with 100 μg of TT:830-843 peptide and 50 μg of LTK63 or with 50 μg of LTR72 or 50 μg of LT as adjuvants. Control mice were immunized with 100 μg of TT:830-843 peptide given alone. After 72 h of culture, supernatants were collected and assayed for IFN-γ by ELISA. The findings with medium alone are also indicated (□).

LTK63 and LTR72 mutants enhance the capacity of HA:307-319 peptide to induce proliferative T-cell responses.

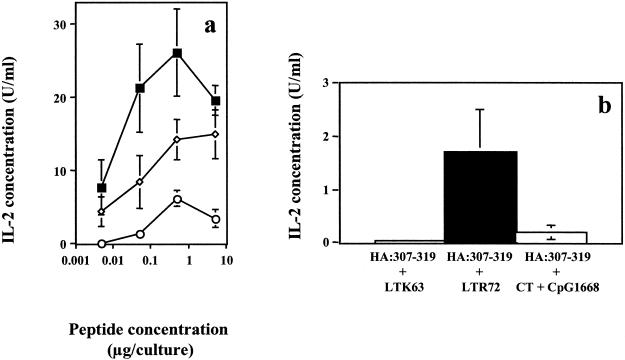

Since both LT mutants were shown to exert an adjuvant effect to the coadministered TT:830-843 peptide and mutant LTR72 in particular stimulated the secretion of high levels of IFN-γ, their adjuvanticity was retested with peptide HA:307-319 as an antigen. In addition, a group of mice were bare-skin immunized with peptide HA:307-319 plus a mixture of CT and an ODN containing the CpG motif 1668 as a positive control. This was based on the observation that the CT-ODN CpG mixture stimulates the production of high levels of IFN-γ (2). As shown in Fig. 5a, splenocyte cultures of mice coimmunized with peptide and mutant LTR72 secreted high levels of IL-2 upon in vitro restimulation with the homologous peptide. This response was significantly higher than that measured in the splenocyte cultures of mice coimmunized with peptide and LTK63 mutant (P = 0.0001 for all peptide concentrations tested). Splenocyte cultures of mice immunized with peptide plus LTR72 secreted IL-2 after restimulation with heat-inactivated influenza virus but not splenocyte cultures of mice immunized with peptide and LTK63 (Fig. 5b).

FIG. 5.

Secretion of IL-2 by splenocytes of mice coimmunized onto bare skin with 100 μg of HA:307-319 peptide and 50 μg of LTK63 (○), with 50 μg of LTR72 (▪), or with a mixture of 100 μg of CpG ODN 1668 and 50 μg of CT (◊). Splenocyte cultures were restimulated in vitro with various concentrations of peptide (a) or with 3 × 103 PFU of heat-inactivated influenza virus (b), and supernatants collected after 72 h of culture were tested for IL-2 secretion with the CTLL-2 IL-2-dependent cell line. The data are presented as IL-2 units/milliliter from hexaplicate cultures for the peptide (a) and from triplicate cultures for the virus (b) ± the SD.

Peptide HA:307-319, like peptide TT:830-843, did not induce any detectable levels of serum anti-peptide antibodies (data not shown), suggesting that it does not contain any B-cell epitope(s).

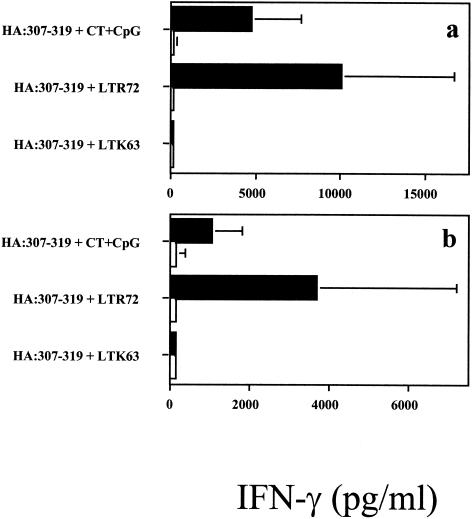

When the production of IFN-γ was measured in the supernatants of splenocyte cultures, only groups of mice that were coimmunized with peptide and LTR72 mutant or with the CT-CpG ODN 1668 mixture gave an IFN-γ response (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Secretion of IFN-γ by HA:307-319 peptide-specific immune splenocytes after in vitro restimulation with 5 μg of homologous peptide (a) or 3 × 103 PFU of heat-inactivated influenza virus (b). Mice were coimmunized onto bare skin with 100 μg of HA:307-319 peptide plus 50 μg of LTK63, with 50 μg of LTR72, or with a mixture of 100 μg of CpG-ODN 1668 and 50 μg of CT. After 72 h of culture, the supernatants were collected and assayed for IFN-γ by ELISA. Results are also shown for medium alone (□).

DISCUSSION

In this study the immunogenicity and adjuvanticity of mutants of E. coli was tested after application onto bare skin. Both LTK63 and LTR72 mutants were shown to be immunogenic, inducing serum and secretory antibody responses. However, mutant LTR72 was the more potent immunogen. This finding extends previous observations on the immunogenicity of LT after skin application (1, 34), demonstrating that two of its mutants—LTK63, which is devoid of ADP-ribosylating activity, and LTR72, which is partially active—can be immunogenic. Furthermore, their ability to generate secretory antibody responses suggests that after application onto bare skin and after their diffusion through the hydrated stratum corneum (that disrupts its barrier function) they might influence the microenvironment of the epidermis. This in turn could favor the migration of antigen-pulsed Langerhans cells to lymphoid organs committed to initiating mucosal immune responses (8).

Adverse reactions to immunization are common and are normally tolerated for the benefit of immunity. In several instances high levels of IgE responses have been noticed with diphtheria toxoid vaccines (19). In the present study, total IgE levels were elevated in the sera of mice receiving LT, LTK63, or LTR72 as adjuvants. Although the exact role of the IgE responses remains to be elucidated, there is always the possibility that the presence of high levels of IgE might be associated with high risk of anaphylaxis, particularly in individuals with atopic predisposition (33). On the other hand, antigen-specific IgE appears to correlate with protection in diseases such as schistosomiasis (17).

Since mutants LTR72 and LTK63 were found to be highly immunogenic, the LT challenge mouse model was selected to evaluate whether immunization onto bare skin can induce protective immune responses against lethal systemic challenge with LT. Despite the vigorous dose of LT, immune mice were significantly protected. This finding is in agreement with observations demonstrating that skin immunization can generate protective immune responses against challenge with a lethal dose of toxins such as CT (12), LT (1), or tetanus (13).

The LTK63 and LTR72 mutants were also effective adjuvants since they enhanced the capacity of topically coapplied peptide antigens to induce antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. Thus, LT mutants with low propensity for adverse side effects have adjuvant activity when they are topically applied, as has been demonstrated after their mucosal delivery (24, 29). Furthermore, their ability to enhance cellular immune responses to peptide antigens extends previous observations demonstrating their adjuvanticity to the topically coapplied diphtheria toxoid (34). However, it should be noted that in the present study two administrations instead of three and a lower dose of each mutant (50 μg instead of 100 μg) were tested.

The molecular mechanisms of adjuvanticity of these mutants are still unclear. From mucosal immunization studies it appears that the enzymatic activity is not an absolute prerequisite for adjuvanticity, since both LTK63 and LTR72 enhance immune responses to coadministered antigens (6, 30). The data of this report, along with the observations of Scharton-Kersten et al. (34), also support this view regarding skin immunization. Several adjuvants with no ADP-ribosylating activity, such as CpG motifs, lipopolysaccharide, muramyl dipeptide, alum, IL-2, and IL-12, have also been shown to enhance antibody responses to topically coapplied diphtheria toxoid (34). However, these responses were short lived and weaker than those induced by CT or LT (34). Thus, it appears that some ADP-ribosylating activity is necessary for enhanced adjuvanticity. The LTR72 mutant, which retains a residual enzymatic activity, is a more potent adjuvant compared to the nontoxic LTK63 mutant after intranasal (6, 10) or skin (34) immunization. Concerning the capacity of mutants to bind to cell surfaces via the GM1 gangliosides (35), studies with nonbinding mutants have demonstrated that binding was necessary for mucosal immunogenicity and adjuvanticity (15, 23). This is also supported by the recent findings of Beignon et al. (1) showing that preincubation of CT with GM1 gangliosides prior to its application onto bare skin results in a significant reduction of systemic and mucosal anti-CT antibody responses. In general, these mutants exert their adjuvant activity mainly on APCs to upregulate major histocompatibility complex and costimulatory molecules and to secrete cytokines (16, 38). This enables Langerhans cells to take up antigens, mature, and migrate to regional lymph nodes, where they present the antigen for the initiation of an adaptive immune response (16).

The ability of small molecules such as synthetic peptides to induce antigen-specific CD4+ T cells after application onto bare skin is particularly important in the context of vaccine design and delivery, since CD4+ T cells help B cells to produce antibodies that neutralize viruses and bacterial toxins, enhance the magnitude of cytotoxic T-cell responses to clear virus-infected cells, and regulate the immune responses to foreign antigens on the basis of cytokine profile they secrete (22). Moreover, the finding that mutant LTR72 preferentially stimulates an IFN-γ response could be advantageous, particularly for the clearance of intracellular pathogens (3). Recent reports have indicated that mutants LTK63 and LTR72 preferentially stimulate Th1- and Th2-type immune responses, respectively, when they are administered in small quantities via the intranasal route (31, 32). However, the type of antigen and the mode of intranasal delivery might influence the induction of a particular Th phenotype, since it has been shown in other systems with peptides (24) or parasite protein antigens (3) that only the LTR72 mutant induces an IFN-γ response. This is also consistent with the results obtained in this study. The exact mechanism(s) of preferential stimulation of IFN-γ secretion by the LTR72 mutant is not clear. If we take into account that ADP-ribosylating exotoxins and their mutants bind to immunocompetent cells (i.e., T cells, B cells, and APCs), it is very difficult to speculate the exact series of in vivo events that favor the secretion of IFN-γ by the LTR72 mutant. However, it could be argued that certain levels of cyclic AMP are critical for the signaling events that will eventually lead to the secretion of IFN-γ (5). This is supported by the findings presented here demonstrating different IFN-γ secretion profiles elicited by LT and its mutants LTR72 and LTK63 (Fig. 4).

Taken together, these findings lead us to conclude that adjuvants such as the LTK63 and LTR72 mutants, which have no or low residual toxicity, hold much promise for the future application of vaccines onto bare skin of humans.

Acknowledgments

This work was in part financed by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Virsol (Paris, France), and Biovector Therapeutics (Toulouse, France). One of the coauthors has competing financial interests.

We thank F. Mawas (National Institute for Biological Standards and Control, London, United Kingdom) for providing the TTx, G. Del Giudice (IRIS Research Center, Chiron, SpA, Siena, Italy) for reviewing the manuscript, and B. Jessel for animal husbandry.

Editor: J. D. Clements

REFERENCES

- 1.Beignon, A.-S., J.-P. Briand, S. Muller, and C. D. Partidos. 2001. Immunization onto bare skin with heat-labile enterotoxin of Escherichia coli enhances immune responses to coadministered protein and peptide antigens and protects mice against lethal toxin challenge. Immunology 102:344-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beignon, A.-S., J.-P. Briand, S. Muller, and C. D. Partidos. 2002. Immunization onto bare skin with synthetic peptides: immunomodulation with a CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotide and effective priming of influenza virus-specific CD4+ T cells. Immunology 105:204-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonenfant, C., I. Dimier-Poisson, F. Velge-Roussel, D. Buzoni-Gatel, G. Del Giudice, R. Rappuoli, and D. Bout. 2001. Intranasal immunization with SAG1 and nontoxic mutant heat-labile enterotoxins protect mice against Toxoplasma gondii. Infect. Immun. 69:1605-1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bos, J. D., and M. L. Kapsenberg. 1993. The skin immune system: its cellular constituents and their interactions. Immunol. Today 14:75-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng, E., L. Cardenas-Freytag, and J. D. Clements. 1999. The role of cAMP in mucosal adjuvanticity of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin (LT). Vaccine 18:38-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Del Giudice, G., and R. Rappuoli. 1999. Genetically derived toxoids for use as vaccines and adjuvants. Vaccine 17:S44-S52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Demotz, S., A. Lanzavecchia, U. Eisel, H. Niemann, C. Widmann, and G. Corradin. 1989. Delinetion of several DR restricted tetanus toxin T-cell epitopes. J. Immunol. 142:394-402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enioutina, E. Y., D. Visic, and R. A. Daynes. 2000. The induction of systemic and mucosal immune responses to antigen-adjuvant compositions administered into the skin:alterations in the migratory properties of dendritic cells appears to be important for stimulating mucosal immunity. Vaccine 18:2753-2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillis, S., M. M. Ferm, W. Ou, and K. A. Smith. 1978. T-cell growth factor: parameters of production and a quantitative microassay for activity. J. Immunol. 120:2027-2032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giuliani, M. M., G. Del Giudice, V. Gianneli, G. Dougan, G. Douce, R. Rappuoli, and M. Pizza. 1998. Mucosal adjuvanticity and immunogenicity of LTR72, a novel mutant of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin with partial knockout of ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. J. Exp. Med. 187:1123-1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glenn, G. M., M. Rao, G. R. Matyas, and C. R. Alving. 1998. Skin immunization made possible by cholera toxin. Nature 391:851. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Glenn, G. M., T. Scharton-Kersten, R. Vassell, C. P. Mallett, T. L. Hale, and C. R. Alving. 1998. Transcutaneous immunization with cholera toxin protects mice against lethal mucosal toxin challenge. J. Immunol. 161:3211-3214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glenn, G. M., T. Scharton-Kersten, R. Vassell, G. R. Matyas, and C. R. Alving. 1999. Transcutaneous immunization with bacterial ADP-ribosylating exotoxins as antigens and adjuvants. Infect. Immun. 67:1100-1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glenn, G. M., D. N. Taylor, X. Li, S. Frankel, A. Montemarano, and C. R. Alving. 2000. Transcutaneous immunization: a human vaccine delivery strategy using a patch. Nat. Med. 6:1403-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guidry, J. J., L. Cardenas, E. Cheng, and J. D. Clements. 1997. Role of receptor binding in toxicity, immunogenicity, and adjuvanticity of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. Infect. Immun. 65:4943-4950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammond, S. A., M. Guebre-Xabier, J. Yu, and G. M. Glenn. 2001. Transcutaneous immunization: an emerging route of immunization and potent immunostimulation strategy. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst. 18:503-526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khalife, J., C. Cetre, C. Pierrot, and M. Capron. 2000. Mechanisms of resistance to S. mansoni infection: the rat model. Parasitol. Int. 49:339-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lipford, G. B., T. Sparwasser, M. Bauer, S. Zimmermann, E.-S. Koch, K. Heeg, and H. Wagner. 1997. Immunostimulatory DNA: sequence-dependent production of potentially harmful or useful cytokines. Eur. J. Immunol. 27:3420-3426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mark, A., B. Bjorksten, and M. Granstrom. 1995. Immunoglobulin E responses to diphtheria and tetanus toxoids after booster with aluminium-adsorbed and fluid DT-vaccines. Vaccine 13:669-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNeal, M. M., J. L. VanCott, A. H. Choi, M. Basu, J. A. Flint, S. C. Stone, J. D. Clements, and R. L. Ward. 2002. CD4 T cells are the only lymphocytes needed to protect mice against rotavirus shedding after intranasal immunization with a chimeric VP6 protein and the adjuvant LT(R192G). J. Virol. 76:560-568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monneaux, F., and S. Muller. 2000. Laboratory protocols for the identification of Th cell epitopes on self-antigens in mice with systemic autoimmune diseases. J. Immunol. Methods 244:195-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mosmann, T. R., and R. L. Coffman. 1989. Th1 and Th2 cells:different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 7:145-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nashar, T. O., H. M. Webb, S. Eaglestone, N. A. Williams, and T. R. Hirst. 1996. Potent immunogenicity of the B subunit of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin: receptor binding is esential and induces differential modulation of lymphocyte subsets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:226-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olszewska, W., C. D. Partidos, and M. W. Steward. 2000. Anti-peptide antibody responses following intranasal immunization: effectiveness of mucosal adjuvants. Infect. Immun. 68:4923-4929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Sullivan, D., T. Arrhenius, J. Sidney, M. F. DelGuercio, M. Albertson, M. Wall, C. Oseroff, S. Southwood, S. M. Colon, F. C. Gaet, et al. 1991. On the interaction of promiscuous antigenic peptides with different DR alleles. Identification of common structural motifs. J. Immunol. 147:2663-2669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Partidos, C. D. 2000. Intranasal vaccines: forthcoming challenges. Pharm. Sci. Technol. Today 3:273-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Partidos, C. D., A.-S. Beignon, V. Semetey, J.-P. Briand, and S. Muller. 2001. The bare skin and the nose as non-invasive routes for administering peptide vaccines. Vaccine 19:2708-2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pizza, M., M. M. Giuliani, M. R. Fontana, G. Douce, G. Dougan, and R. Rappuoli. 2000. LTK63 and LTR72, two mucosal adjuvants ready for clinical trials. Int. J. Microbiol. 290:455-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pizza, M., M. M. Giuliani, M. R. Fontana, E. Monaci, G. Douce, G. Dougan, K. H. G. Mills, R. Rappuoli, and G. Del Giudice. 2001. Mucosal vaccines: nontoxic derivatives of LT and CT as mucosal adjuvants. Vaccine 19:2534-2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rappuoli, R., M. Pizza, G. Douce, and G. Dougan. 1999. Structure and mucosal adjuvanticity of cholera and Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxins. Immunol. Today 20:493-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryan, E. J., E. McNeela, G. A. Murphy, H. Steward, D. O'Hagan, M. Pizza, R. Rappuoli, and K. H. G. Mills. 1999. Mutants of Escherichia coli heat-labile toxin act as effective mucosal adjuvants for nasal delivery of an acellular pertussis vaccine: differential effects of the nontoxic AB complex and enzyme activity on Th1 and Th2 cells. Infect. Immun. 67:6270-6280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryan, E. J., E. McNeela, M. Pizza, R. Rappuoli, L. O'Neill, and K. H. G. Mills. 2000. Modulation of innate and acquired immune responses by Escherichia coli heat-labile toxin: distinct pro- and anti-inflammatory effects of the nontoxic AB complex and the enzyme activity. J. Immunol. 165:5750-5759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakaguchi, M., and S. Inouye. 2000. IgE sensitization to gelatin: the probable role of gelatin-containing diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis (DTaP) vaccines. Vaccine 18:2055-2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scharton-Kersten, T., J.-M. Yu, R. Vassell, D. O'Hagan, C. R. Alving, and G. M. Glenn. 2000. Transcutaneous immunization with bacterial ADP-ribosylating exotoxins, subunits, and unrelated adjuvants. Infect. Immun. 68:5306-5313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spangler, B. D. 1992. Structure and function of cholera toxin and the related Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin. Microbiol. Rev. 56:622-647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams, I. R., and T. S. Kupper. 1996. Immunity at the surface: homeostatic mechanisms of the skin immune system. Life Sci. 58:1485-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamamoto, S., Y. Takeda, M. Yamamoto, H. Kurazono, K. Imaoka, M. Yamamoto, K. Fujihashi, M. Noda, H. Kiyono, and J. R. McGhee. 1997. Mutants in the ADP-ribosyltransferase cleft of cholera toxin lack diarrheagenicity but retain adjuvanticity. J. Exp. Med. 185:1203-1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamamoto, M., H. Kiyono, S. Yamamoto, E. Batanero, M. N. Kweon, S. Otake, M. Azuma, Y. Takeda, and J. R. McGhee. 1999. Direct effects on antigen-presenting cells and T lymphocytes explain the adjuvanticity of a nontoxic cholera toxin mutant. J. Immunol. 162:7015-7021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]