ABSTRACT

Purpose

To validate a computerized expert system evaluating visual fields in a prospective clinical trial, the Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Decompression Trial (IONDT). To identify the pattern and within-pattern severity of field defects for study eyes at baseline and 6-month follow-up.

Design

Humphrey visual field (HVF) change was used as the outcome measure for a prospective, randomized, multi-center trial to test the null hypothesis that optic nerve sheath decompression was ineffective in treating nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy and to ascertain the natural history of the disease.

Methods

An expert panel established criteria for the type and severity of visual field defects. Using these criteria, a rule-based computerized expert system interpreted HVF from baseline and 6-month visits for patients randomized to surgery or careful follow-up and for patients who were not randomized.

Results

A computerized expert system was devised and validated. The system was then used to analyze HVFs. The pattern of defects found at baseline for patients randomized to surgery did not differ from that of patients randomized to careful follow-up. The most common pattern of defect was a superior and inferior arcuate with central scotoma for randomized eyes (19.2%) and a superior and inferior arcuate for nonrandomized eyes (30.6%). Field patterns at 6 months and baseline were not different. For randomized study eyes, the superior altitudinal defects improved (P = .03), as did the inferior altitudinal defects (P = .01). For nonrandomized study eyes, only the inferior altitudinal defects improved (P = .02). No treatment effect was noted.

Conclusions

A novel rule-based expert system successfully interpreted visual field defects at baseline of eyes enrolled in the IONDT.

INTRODUCTION

The Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Decompression Trial (IONDT) was a randomized prospective study designed to establish the safety and efficacy of optic nerve sheath decompression as a treatment for nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION), as well as to document the natural history of NAION.1 Based upon visual acuity as the primary outcome measure, the IONDT demonstrated that optic nerve sheath decompression is not effective and may be harmful.2

For NAION, characterized clinically as causing visual field loss, basing conclusions about efficacy of treatment and natural history solely on visual acuity may be inadequate. For this reason, the Humphrey visual field (HVF) was included in the study as a secondary outcome measure. Quantitative assessment of visual field function has been aided considerably by the advent of computerized automated static perimeters such as the HVF analyzer (Humphrey Instruments, Dublin, California). These instruments provide a standardized testing environment, quantitative assessment of threshold sensitivity to spots of light at fixed points throughout the visual field, and some data regarding reliability of patients’ responses.

Initial visual field evaluation based only on a readily computed global measure, mean deviation, failed to distinguish any difference between surgical and observational management. However, mean deviation alone may not be an adequate measure for assessment of eyes with NAION. The classic patterns of defect encountered in this disease may shift without changing average loss. Furthermore, there may be important changes in sensitivity within small areas of the visual field corresponding to nerve fiber bundle defects. These may not be detected when averaged into the mean deviation calculation. Therefore, a more detailed analysis of the quantitative visual field testing is important, even though such an analysis was not originally part of the IONDT methodology.

Whereas visual acuity based upon the logMAR charts developed for the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study is a simple, well-tested measure of visual function, visual field assessment is complex and well beyond the scope of the original analysis. Prospective glaucoma trials have utilized a number of approaches for evaluating progression, but the algorithms seldom include classifications based upon the type of defect. The Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial categorized visual field defects, but the methodology did not involve strict definitions for classification. Furthermore, patterns of field loss were qualitatively rather than quantitatively determined.3 In the context of a prospective clinical trial, an automated, objective classification may be preferable.

For the current study, a Visual Field Analysis Committee was formed in 1998, consisting of neuro-ophthalmologists from six of the 26 participating Clinical Centers. As an initial step, each member of this group classified the visual fields of patients with NAION but not enrolled in the study. Using an iterative process to achieve consensus, a set of rules was devised to categorize the visual defects encountered in the disease. These rules were then incorporated into a computerized expert system to analyze the study fields in a consistent, reproducible manner.

The validated computerized expert system, described in detail herein, was used to determine the pattern of defect present as well as the density of defect within each pattern for both enrolled and fellow eyes. Based upon the categorization from the computerized expert system, a detailed evaluation of baseline visual field defects noted by HVF for patients enrolled in the IONDT was performed. The 6-month visual field for each patient was then compared quantitatively to the visual field at baseline, allowing for short-term fluctuations in each data set. The following questions were addressed:

Are the pattern and severity of visual field defects found in eyes randomized to treatment similar to those randomized to careful follow-up?

Is the pattern or severity of visual field defects found in eyes with better than 20/64 visual acuity substantially different from those with worse acuity who were eligible for randomization?

Are there preexisting conditions (eg, diabetes, hypertension) that affect the pattern and severity of visual field defects?

What is the relationship between global indices of HVF performance and the pattern or severity of visual field defects?

What is the relationship between visual acuity and pattern or severity of visual field defect?

Are visual field defects present in fellow eyes without known optic neuropathy that may indicate the presence of subclinical optic disk ischemia?

Are there changes in the visual fields between baseline and 6-month visits for randomized eyes, nonrandomized study eyes, and fellow eyes?

Are there changes in the visual fields for eyes randomized to surgery as compared to careful follow-up?

METHODS

Study Protocol

The eligibility criteria, randomization procedure, and visit protocols are extensively described in prior publications.1 Briefly, patients aged 50 or above were eligible for randomization into surgical and careful observation groups if they had symptoms and signs characteristic of NAION and their visual acuity was 20/64 or less. A Late Entry subset of the randomized patients included eyes for which acuity in the study eye was better than 20/64 at baseline but lost acuity to below this level within 30 days. Patients with acuity better than 20/64 were followed but not randomized. Fellow eyes were tested, and the results were recorded. At the time of examination, the clinician determined whether the fellow eye had optic neuropathy (of any type) or not. Visual fields were obtained at baseline, 6 months, 12 months, and at closeout of the study. Although multiple replications of the fields at some or all evaluation visits might have been helpful in minimizing training effects, fatigue effects may have increased because only time-consuming standard threshold strategies were available at the outset of the study. All centers utilized protocols approved by investigational review boards at their respective institutions. Patients were enrolled between 1992 and 1994. At that time the Data Safety and Monitoring Committee halted further recruitment, because surgery was found not to be effective.2

Organizational Structure

The Data Coordinating Center maintained the IONDT database that included visual field results from HVFs (both hard copies and diskettes). The Center masked and forwarded hard copies of visual fields to the visual field committees. The Center performed statistical analyses on the results of visual field analyses as well as other measures.

A Visual Field Steering Committee was formed at the outset of the study, evolving by 1994 to consist of the Director of the Visual Field Analysis Center (VFAC), the Director and key members of the Data Coordinating Center, and a consultant expert in visual field analysis. The VFAC developed the visual field assessment protocol and ensured that all visual fields were of good quality, masked as to patient and group identities, and handled appropriately. The committee reviewed and approved the procedures for conduct of the study, resolved technical issues arising during the course of the study, and reviewed study progress, acting when necessary to correct deficiencies. It also set the priorities for the visual field portion of the study and provided oversight for study analysis and publications.

An expert panel was formed in 1996, consisting of the Director of the VFAC and five other neuro-ophthalmologists with expertise in the interpretation of visual fields. It was responsible for developing and validating a computerized expert system, based on an agreed-upon set of rules for identification of the various types of field defects. The VFAC maintained the digital file inventory of all analyzed fields that were then forwarded to the Data Coordinating Center.

Determination of Quality

Visual fields were evaluated for compliance with the protocol,1 that is, that the field was a 24-2 performed on a HVF using test stimulus size III with the foveal sensitivity switch “on.” The IONDT did not utilize 30-2 visual fields because the additional peripheral test points were considered too variable. A few 30-2 visual fields that otherwise corresponded with the protocol were analyzed by utilizing only those points also represented on the 24-2 HVF test. The number and percentages of false-positive responses, false-negative responses, and fixation losses were recorded. Although unreliable fields in severely affected patients might have contained useful information, the interpretation would not be meaningful; thus, they were excluded from analysis. Visual fields were included for analysis if they were deemed reliable, using the four basic criteria of the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study (CIGTS) intra-test reliability rating.4 If fixation losses were greater than 20% for more than 20 trials, one point was added. If false-positives for eight or more trials were 33% or greater, one point was added. A similar criterion was applied for false-negatives. Short-term fluctuation (dB) was rated at zero for less than or equal to 4.0, one if greater than 4.0 but less than or equal to 6.0, two if greater than 6.0 but less than or equal to 7.0, and three if greater than 7.0. A rating of less than four was considered reliable.

Classification of Visual Fields

Validation of a system for classifying visual fields is complex. Given that there is no “gold standard,” experts will likely disagree on interpretation. This problem is well known in medicine. For instance, studies validating the use of computer-assisted diagnosis tools5–7 suggest that the differences between computer diagnosis and human expert diagnosis vary to about the same extent as human experts disagree among themselves. Given that computerized diagnosis may be no better than that of an expert panel, the principal reason for utilizing a computerized expert system in the context of a clinical trial is to reduce inconsistency by eliminating intraobserver and interobserver variability.

In the absence of a “gold standard,” validation of a classification system for visual fields requires several steps.5–7 First, an expert panel needs to achieve consensus on a set of rules. Second, the experts should be able to apply these rules in such a manner that the rate of disagreement is not different from that reported for similar classifications in other medical contexts. Third, the consistent application of the rules by a computerized expert system should produce classifications that do not disagree with the panel more than the expert panel disagrees with itself. Finally, the computerized expert system should reach reasonable clinical interpretations, such that major disagreements with the expert panel are rare.

The number of experts required on the panel was determined after a statistical computation determined that the chance of all six experts agreeing on ten patterns by guessing would be 0.00001. A majority of the experts needed to agree to categorize a field defect as a specific pattern. The chance of this degree of concordance occurring by guessing alone was .01215. For any field in which the agreement among panelists was not significantly better than guessing, the field was called “nonclassifiable.”

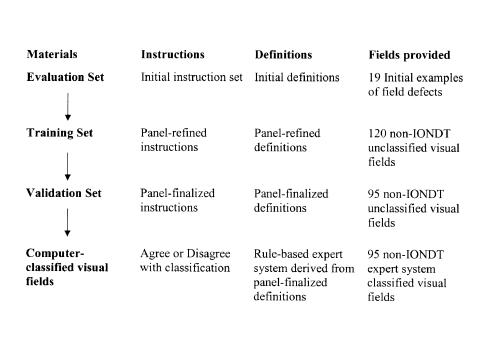

A sequence similar to that used by Molino and associates5 was developed to facilitate derivation of the rules, as shown in Figure 1. The information associated with this sequence was formulated into “sets” and included an evaluation set, a training set, and a validation set.

Figure 1.

Sequence developed to facilitate derivation of the rules used for classification system for visual fields.

Evaluation Set

The Visual Field Steering Committee developed an evaluation set for each of the six expert panelists. It consisted of instructions to the panelists, a set of proposed definitions for 13 types of defects and for severity accompanied by a series of 19 examples thought to correspond to the proposed definitions, a grading form, and a set of sample visual fields from nonstudy patients with AION for analysis.

Using preliminary definitions as modified by the expert panel, an initial classification was made for the 19 visual fields provided in the evaluation set. Many of these fields contained more than one type of pattern defect. The panelists then independently reported the degree to which they agreed with the classification. In addition, the panelists were instructed to categorize the density of the defect as mild, moderate, severe, or absolute. Results are shown in Table 1. Based upon this exercise, additional revisions of the definitions were deemed necessary. Of importance, three separate categories of scotoma were identified: peripheral, paracentral, and central. Also, an admonition was added to the instructions that the category of “other” be utilized only for visual fields that were impossible to fit into a specific category.

Table 1.

Expert panelists’ degree of agreement with classification of 19 examples of visual fields

| Pattern | Excellent | Good | Uncertain | Poor | Bad |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 83% | 17% | |||

| Absolute defect | 100% | ||||

| Mild diffuse depression | 50% | 17% | 33% | ||

| Severe diffuse depression | 17% | 66% | 17% | ||

| Mild superior altitudinal | 50% | 50% | |||

| Moderate superior and inferior altitudinal | 66% | 17% | 17% | ||

| Severe superior altitudinal | 100% | ||||

| Mild inferior altitudinal | 33% | 67% | |||

| Moderate inferior altitudinal | 17% | 50% | 33% | ||

| Severe inferior altitudinal and moderate superior arcuate | 83% | 17% | |||

| Moderate superior arcuate | 67% | 17% | 17% | ||

| Severe superior and inferior arcuates | 33% | 33% | 17% | 17% | |

| Mild inferior arcuate | 100% | ||||

| Moderate inferior arcuate | 67% | 17% | 17% | ||

| Severe inferior arcuate | 67% | 33% | |||

| Moderate inferior nasal step | 83% | 17% | |||

| Mild paracentral scotoma | 33% | 17% | 50% | ||

| Moderate central scotoma | 67% | 33% | |||

| Severe central scotoma | 50% | 50% |

Training Set

Using the final instructions and forms derived from the evaluation set, the expert panel analyzed 120 masked, representative nonstudy NAION fields. IONDT fields were not utilized for training in order to preserve the integrity of the classification tool. To assess the ability of the panelists to accurately apply the rules, 10 of these fields were duplicates and 10 were example fields from the evaluation set. For 55 of the analyzed fields, at least 83% agreed on the categorization without any collaboration among experts. Agreement on classification of the remaining 65 fields was achieved through a series of four interactive reconciliation meetings of the expert panel, held either by teleconference or face-to-face. These resulted in refinement of the pattern definitions and consensus on interpretation of the fields in the training set. These rules were then programmed into the computerized expert system.

The consensus derived from the training set included identification of 14 different field types, shown in Table 2. Severity was restricted to mild, moderate, or severe. General rules for classification included the following:

If a field is noted as normal or as an absolute defect, no other notations can be made.

A depressed point is defined as equal to or greater than 4-dB loss.

An attempt should be made to classify fields even though they may appear unreliable from the indices.

Severity is based upon subjective judgment. Only the arcuate/altitudinal category can have more than one severity with a separate severity assignable to the arcuate and the altitudinal components.

Table 2.

Types of field defects based on consensus of interpretation

| Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Normal | No quadrants depressed or only a few points in no specific pattern. One depressed point in a location surrounding the blind spot is normal unless it is part of another defined field defect. |

| Absolute defect | No response (sensitivity = zero) was recorded for all points in all quadrants or if only one point is less than or equal to 9 dB sensitivity and all other points are zero. If the retest is zero, then the point sensitivity is zero. Foveal sensitivity must be equal to zero. |

| Diffuse depression | Entire visual field equally depressed, including fixation as defined as presence of both a superior and an inferior altitudinal defect that are equally depressed and a central scotoma. |

| Superior altitudinal | Upper half of field equally depressed as defined as all points in the superior two quadrants approximately equally depressed, excluding those nasal to the blind spot (ie, points 11 and 19 on the visual field map). Depression should extend down to horizontal meridian including approximate equal involvement of the superior paracentral points (points 21 and 22 on the visual field map). |

| Inferior altitudinal | Lower half of field equally depressed as defined as all points in the inferior two quadrants approximately equally depressed, excluding those nasal to the blind spot (ie, points 27 and 35 on the visual field map). Depression should extend up to horizontal meridian, including approximate equal involvement of the superior paracentral points (points 29 and 30 on the visual field map). |

| Superior arcuate | Peripheral defect (at least four peripheral points must be depressed within one quadrant) that appears in either or both superior quadrants with relative sparing of either one or both of the superior paracentral points, or either one of the superior paracentral points is less depressed in comparison to the superior periphery in either quadrant and it is not a nasal step. Superior periphery is defined as all points in the superior two quadrants except points 21 and 22. |

| Inferior arcuate | Peripheral defect (at least four peripheral points must be depressed within one quadrant) that appears in either or both inferior quadrants with relative sparing of either one or both of the inferior paracentral points, or either one of the inferior paracentral points is less depressed in comparison to the inferior periphery in either quadrant and it is not a nasal step. Inferior periphery is defined as all points in the inferior two quadrants except points 29 and 30. |

| Superior nasal step | An isolated superior nasal quadrant defect which preferentially involves the peripheral points (points 18, 25, and 26) adjacent to the horizontal meridian. Cannot be part of a superior arcuate defect and there cannot be an arcuate defect in the superior temporal quadrant. Superior nasal points adjacent to the vertical meridian (points 3, 8, 15, and 22) are relatively spared. |

| Inferior nasal step | An isolated inferior nasal quadrant defect which preferentially involves the peripheral points (points 33, 34, and 42) adjacent to the horizontal meridian. Cannot be part of an inferior arcuate defect and there cannot be an arcuate defect in the inferior temporal quadrant. Inferior nasal points adjacent to the vertical meridian (points 30, 39, 46, and 51) are relatively spared. |

| Central scotoma | Decreased sensitivity of the fovea by 5 dB relative to the least depressed point in the rest of the field or the foveal sensitivity is less than 10 dB. |

| Paracentral scotoma | Focal depression of the visual field not corresponding to any other pattern and located within the paracentral region (points 20, 21, 22, 28, 29, 30) adjacent to the blind spot, but sparing fixation (ie, no central scotoma). One isolated, depressed paracentral point next to the blind spot (point 20 or 28) is not a paracentral scotoma. If there is a central scotoma and, as defined, a paracentral scotoma, then the defect is categorized as a central scotoma. |

| Superior arcuate/altitudinal | Both superior paracentral points (points 21 and 22) are equally depressed, but the superior periphery is more depressed than the paracentral. Superior paracentral points must differ substantially from the inferior paracentral points (points 29 and 30), ie, no central or paracentral scotoma involving these points. |

| Inferior arcuate/altitudinal | Both inferior paracentral points (points 21 and 22) are equally depressed, but the inferior periphery is more depressed than the paracentral. Inferior paracentral points must differ substantially from the superior paracentral points (points 29 and 30), ie, no central or paracentral scotoma involving these points. |

| Other | Pattern defect that does not fit any of the above definitions, eg, shifted field. Use this category only if you are certain that you cannot categorize the defect using the other 13 categories. |

Validation Set

Having determined the rules for classification, another set of 95 non-IONDT visual fields was sent to the expert panel as a validation set. The classification results from each panelist were determined (Table 3). The agreement obtained from the panel was then compared with the classifications obtained from the computer program. The level of agreement is shown in Table 4. There was a large percentage of internal disagreement among the panelists as to classification of fields within the validation set, despite a common set of rules derived by consensus. In turn, there was disagreement between the panel and the computer program.

Table 3.

Agreement in classification of 95 visual fields among readers

| Amount of agreement | No. of fields | % of total fields |

|---|---|---|

| 6 of 6 readers agree | 7 | 7 |

| 5 of 6 readers agree | 14 | 15 |

| 4 of 6 readers agree | 23 | 24 |

| 3 of 6 readers agree | 22 | 23 |

| 2 of 6 readers agree | 25 | 26 |

| None agree | 4 | 4 |

| Total | 95 | 100 |

Table 4.

Agreement by computer in classification of 66 fields where there was agreement of at least 3 of 6 readers in defect classification

| No. of fields for stated level of agreement between experts | No. of fields for which computer and panel agreed | % of fields for which computer and panel agreed |

|---|---|---|

| In 7 fields where 6 of 6 readers agreed | 7 | 100 |

| In 14 fields where 5 of 6 readers agreed | 10 | 71 |

| In 23 fields where 4 of 6 readers agreed | 16 | 70 |

| In 22 fields where 3 of 6 readers agreed | 16 | 73 |

| Total (in 66 visual fields with agreement) | 50 | 66 |

The inability of the experts to independently agree with each other or the computer is consistent and of the same order of magnitude as reported in the literature for instances for which no gold standard exists.5 This result reinforces the need, within the context of a large clinical trial, to have a computerized system for consistent application of clinically meaningful rules.

Due to the lack of consensus, a second method of validation was performed. In this method, the computer program evaluated all the fields, and the panelists were asked to agree or disagree with the computer results. This method changed the question asked of the experts from “How would you try to apply rules to classify a defect?” to “Does the consistent application of consensus-derived rules applied by the computer result in a classification that is clinically acceptable?”

With the new method of validation, in only four instances was there initial disagreement with the computer by half or more of the panelists, as shown in Table 5. These were determined to be secondary to data entry errors in two instances and due to computer criteria differentiating altitudinal from arcuate defects in two instances. In the latter instances, investigation revealed that further manipulation of the computer algorithm to allow concordance with the panel would result in other classification errors; therefore, these discrepancies were allowed to stand. There was majority agreement between the computer and the expert panel in 91 (94%) of 95 fields, indicating that incorporation of the rules into a computer program unanimously agreed upon by the expert panel was a valid method for analysis of the patterns and severities of the visual field data collected by the IONDT.

Table 5.

Defect pattern agreement between computer and expert panel

| Agree/total | No. of fields | % of fields |

|---|---|---|

| 6/6 | 59 | 62 |

| 5/6 | 24 | 25 |

| 4/6 | 8 | 8 |

| 3/6 | 2 | 2 |

| 2/6 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 95 | 100 |

The Computer-Based Expert System

Data Entry

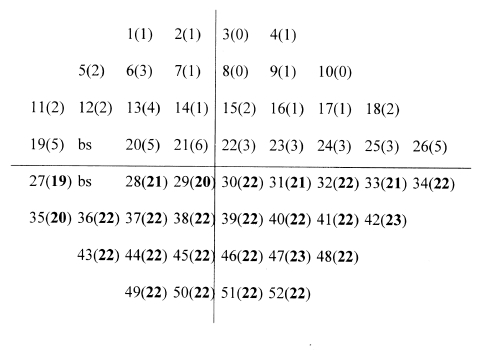

Humphrey visual field data consisted of five components: (1) visual field identification (patient number, visit number, and eye examined), (2) reliability indices (fixation losses, false-positives, and false-negatives), (3) foveal sensitivity (dB) and highest point of sensitivity for the whole field (dB), (4) dB loss at each of the 52 data points on the total deviation plot, and (5) short-term fluctuation. For each visual field, the location and dB loss (if any) at each of the 52-point locations is entered into an Excel database on a personal computer (Figure 2). In addition, the foveal sensitivity was recorded, and in instances of diffuse depression, the absolute sensitivity of each point was entered. Although digitized data in the form of floppy disks and flat files were available, changes in computer hardware and software precluded their use in constructing the database. Therefore, the printed visual fields were transcribed into a Microsoft 97/00 Excel compatible database, using double-entry verification.

Figure 2.

Location and decibel loss at each of 52 data points on the total deviation plot.

Software Structure

The computer-based expert system was constructed as a rule-based system on an Excel platform, running under Windows 98, evaluating each field quadrant-by-quadrant. Each rule consisted of a logical statement that could be found true or false, taking the form “if…then.” A truth table was utilized to define specific types of field defects, based upon definitions of the expert panel. Two forms of logical statements were used to identify pattern defects. The first form was based upon average dB loss within a quadrant corresponding to a particular pattern. If no average depression was present, then the number of disturbed points within a quadrant was used to determine the presence of pattern defects. Thus, the numbers of disturbed points were used primarily to find mild defects that were missed by averaging. A listing of the algorithms utilized by the expert system is included in the Appendix.

For instance, if the average dB loss is greater in the periphery than in the central field by 5 dB, then an arcuate defect is present in that quadrant. If the central dB loss is greater by 5 dB than the periphery, then a central or paracentral defect is present. If no pattern defect can be found by averaging, then disturbed point algorithms are used to find mild or smaller pattern defects within a quadrant. A disturbed point is defined as >3-dB loss. If there are a predetermined number of disturbed points within the boundary of a pattern, then the defect is detected. Some pattern defects are determined by the presence or absence of other defects. For example, if there is a superior and an inferior altitudinal defect and a central scotoma, then the pattern is a diffuse depression. If there is a paracentral scotoma and a central scotoma, then there is just a central scotoma. Average dB loss within a pattern defect is used to determine severity, as shown in Table 6. In the instance of determining absolute defect, the expert computer system operator reviews all fields noted to have diffuse depression; then, actual sensitivity rather than relative sensitivity loss is used to determine whether or not the field has an absolute defect.

Table 6.

Determination of severity of field defects, based upon a non-iondt field test analysis

| Severity | n | Average dB loss | 95% CI | Average no. points | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | 1 | 6.2 | 5 | ||

| Moderate | 5 | 18.2 | 12.9–23.5 | 25 | 24.3–25.7 |

| Severe | 17 | 27.43 | 26.3–28.5 | 26 | 25.8–26.2 |

CI, confidence interval; IONDT, Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Decompression Trial.

Calculation of Pattern Changes Between 6-month and Baseline Visits

Longitudinal evaluation of changes in the visual fields for individual patients between baseline and the 6-month follow-up visit was determined by modification of the computerized expert system to correct for short-term fluctuation. The joint short-term fluctuation (SF) was calculated as follows: SF = Sqrt (SFbaseline2 + SF6-month2). The baseline visit HVF sensitivities were not altered. The HVFs from the 6-month visit were altered ±1.96 SF at test loci that differentiate arcuate from altitudinal (points 21 and 22 or points 29 and 30 in Figure 2), central from paracentral defects (foveal sensitivity), and absence of defect from arcuate, altitudinal, central, and paracentral defects. For instance, let us assume an eye has a superior arcuate scotoma at baseline but an altitudinal defect at the 6-month visit. Since relative sparing of paracentral points 21 and 22 for the upper visual field distinguishes an arcuate from an altitudinal defect, the two paracentral points from the 6-month visit were increased in sensitivity by 1.96 times the SF for that field. If the difference in field pattern persisted despite this manipulation, then the follow-up field was determined as “changed.” If the difference in field pattern disappeared due to this manipulation, then the follow-up visual field was determined as “not changed.”

Statistical Methods

Data analysis was carried out using Stata statistical software for Windows (StataCorp 2001, Stata Statistical Software: Release 7.0; Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas). SPSS software for Windows was used to produce some of the tables (SPSS Inc 1998, SPSS: Release 8.0.1; SPSS, Chicago, Illinois). All statistical tests were two-tailed. Techniques included paired and unpaired Student t tests, the Fisher exact test, Kendall tau-b test for association of ordinal variables, Mantel-Haenszel extension test, and Stuart-Maxwell test of marginal homogeneity producing a chi-square test with 2 degrees of freedom, as appropriate.

RESULTS

Baseline Visual Fields

Visual fields were available on 247 randomized eyes, 158 nonrandomized study eyes, 79 fellow eyes with optic neuropathy at baseline, and 326 fellow eyes with no optic neuropathy at baseline (total 810). A total of 13 fields could not be scored for reliability, three fields were determined to be unreliable, and four fields were 30-2 programs for which data were unavailable for analysis. The frequency of unreliable visual fields was similar to the 1% found by Katz and associates,4 using the same CIGTS criteria. Of the remaining reliable fields, 38 had no foveal sensitivity. Baseline visual fields were available for analysis on 229 study eyes randomized to either surgery or careful observation. Baseline visual fields were also available on an additional 147 eyes with vision better than 20/64 followed with careful observation. Fellow eyes were also evaluated at baseline. Of the 376 fellow eyes, 75 were identified at baseline as having optic neuropathy and 301 were identified at baseline as having no optic neuropathy. These data included four 30-2 visual fields for which points not covered by the 24-2 field were not analyzed and 16 Fast-Pac program fields.

Distribution of Field Defect Patterns by Category

The distribution of defect patterns for the various categories of eyes is summarized in Tables 7A and 7B. There was no detectable difference between the frequency of various patterns of field defect comparing eyes randomized to surgery and careful follow-up. Therefore, all randomized eyes are shown as a single group. Differences were observed between the randomized and the observation groups. Central scotomas were much more frequent in the randomized study eyes than in the observation study eyes. The most commonly observed defect in the randomized group of 229 eyes was a superior and inferior arcuate defect with central scotoma in 44 eyes (19.2%), followed by superior arcuate defect and inferior altitudinal defect with central scotoma in 39 eyes (17.0%).

Table 7a.

Categorization of field defects at baseline, by patient group and eye

| Study eye:randomized | Study eye:observation | Fellow eye: with optic neuropathy | Fellow eye: no optic neuropathy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pattern | No. | Col % | No. | Col % | No. | Col % | No. | Col % |

| Normal | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 47 | 15.6 |

| Superior arcuate isolated | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 35 | 11.6 |

| Inferior arcuate isolated | 1 | 0.4 | 16 | 10.9 | 1 | 1.3 | 20 | 6.6 |

| Superior + inferior arcuates | 6 | 2.6 | 45 | 30.6 | 10 | 13.3 | 169 | 56.1 |

| Superior + inferior arcuates +paracentral | 11 | 4.8 | 10 | 6.8 | 2 | 2.7 | 3 | 1.0 |

| Superior + inferior arcuates +central scotoma | 44 | 19.2 | 10 | 6.8 | 6 | 8.0 | 7 | 2.3 |

| Superior arcuate + inferior altitudinal | 3 | 1.3 | 17 | 11.6 | 4 | 5.3 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Superior arcuate + inferior altitudinal + central scotoma | 39 | 17.0 | 8 | 5.4 | 14 | 18.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Superior altitudinal + inferior arcuate | 5 | 2.2 | 6 | 4.1 | 8 | 10.7 | 3 | 1.0 |

| Superior altitudinal + inferior arcuate + central scotoma | 19 | 8.3 | 3 | 2.0 | 5 | 6.7 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Superior + inferior altitudinal | 13 | 5.7 | 5 | 3.4 | 3 | 4.0 | 2 | 0.7 |

| Diffuse depression | 30 | 13.1 | 1 | 0.7 | 10 | 13.3 | 1 | 0.3 |

| Absolute defect | 30 | 13.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 8.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other: isolated defect | 3 | 1.3 | 4 | 2.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 1.7 |

| Other: 2 or more defects | 24 | 10.5 | 18 | 12.2 | 6 | 8.0 | 7 | 2.3 |

| Total | 229 | 100 | 147 | 100 | 75 | 100 | 301 | 100 |

Table 7b.

Further characterization of field defects at baseline by patient group and eye

| Study eye: randomized | Study eye: observation | Fellow eye: no optic neuropathy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pattern (isolated or in combination) | No. | Col % | No. | Col % | No. | Col % | |

| Any superior defect | No | 73 | 31.9 | 30 | 20.4 | 79 | 26.2 |

| Yes | 156 | 68.1 | 117 | 79.6 | 222 | 73.8 | |

| Any inferior defect | No | 67 | 29.3 | 9 | 6.1 | 92 | 30.6 |

| Yes | 162 | 70.7 | 138 | 93.9 | 209 | 69.4 | |

| Any superior or inferior defect | No | 63 | 27.5 | 5 | 3.4 | 57 | 18.9 |

| Yes | 166 | 72.5 | 142 | 96.6 | 244 | 81.1 | |

| Any scotoma | No | 91 | 39.7 | 99 | 67.3 | 283 | 94.0 |

| Yes | 138 | 60.3 | 48 | 32.7 | 18 | 6.0 | |

| Any diffuse defect | No | 169 | 73.8 | 146 | 99.3 | 296 | 98.3 |

| Yes | 60 | 26.2 | 1 | 0.7 | 5 | 1.7 | |

Central scotoma is part of the definition for both diffuse depression in 30 randomized eyes (13.1%) and absolute defect in 30 randomized eyes (13.1%). Excluding diffuse defects, central or paracentral scotoma was present, either isolated or in combination, in 138 eyes (60.3%) (Table 7B). By comparison, the most commonly observed visual field in the 147 nonrandomized study eyes was a combined superior and inferior arcuate defect in 45 eyes (30.6%) followed by superior arcuate and inferior altitudinal defect in 17 eyes (11.6%) and isolated inferior arcuate defect in 16 eyes (10.9%), none of which included central scotoma. Central or paracentral scotoma, isolated or in combination, occurred in only 48 of the nonrandomized study eyes (32.7%). The difference in distribution is not surprising, because central scotoma includes foveal sensitivity as part of its definition. Another notable difference was that there was only a single instance of diffuse defect for the study observation group.

Fellow eyes with optic neuropathy were more widely distributed regarding the patterns of field loss encountered, possibly because these 75 eyes were not segregated according to visual acuity (Table 7A). Using the established criteria, the computerized expert system identified only 47 (15.6%) of 301 fellow eyes without optic neuropathy as having normal visual fields. The most commonly encountered abnormalities were isolated superior arcuate defects in 35 eyes (11.6%), isolated inferior arcuate defects in 20 eyes (6.6%), and, especially, combined superior and inferior arcuate defects in 169 eyes (56.1%). Severity of 35 superior arcuate defects in nonoptic neuropathy fellow eyes was mild in 33 (94.3%), and severity of 169 combined superior and inferior arcuate defects was mild in 100 eyes (59.2%) (Table 8). A severe defect was included in only 9 (5.3%) of 169 fellow eyes that had superior and inferior arcuate defects with no optic neuropathy. Scotomas were noted in only 18 eyes in this group (6%). Diffuse defects were even more rare, present in only 5 eyes (1.7%) (Table 7B).

Table 8a.

Severity of superior arcuate isolated defects in fellow eyes

| Defect | n | Col % |

|---|---|---|

| Mild only | 33 | 94.3 |

| Moderate only | 2 | 5.7 |

| Total | 35 | 100.0 |

Characteristics of Visual Fields for Late-Entry Randomized Eyes

The patterns of visual field defects for eyes randomized at regular entry (n = 175) were compared to those randomized at late entry due to progression of acuity loss (n = 54). Results are summarized in Table 9. Diffuse depression was present in 27 (15.4%) of the eyes randomized to regular entry, and an absolute defect was present in 24 (13.7%) of these eyes. By comparison, diffuse depression was present in only 3 (5.6%) of the eyes randomized to late entry, and an absolute defect was present in 6 (11.1%) of these eyes. The combination of superior altitudinal and inferior arcuate defects with central scotoma was noted in 11 eyes (6.3%) randomized to regular entry compared to 8 eyes (14.8%) of those randomized in the late-entry group. Although there was a trend for the patterns of defects seen in the regular-entry and late-entry groups to be different, this difference did not reach statistical significance (Fisher’s exact test, P = .078).

Table 9a.

Categorization of field defects at baseline, by randomized entry and eye

| Categorization by time of randomization |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized regular entry | Randomized late entry | |||

| Pattern | No. | Col % | No. | Col % |

| Normal | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Inferior arcuate isolated | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Superior + inferior arcuate | 2 | 1.1 | 4 | 7.4 |

| Superior + inferior arcuate + paracentral scotoma | 11 | 6.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Superior + inferior arcuate + central scotoma | 36 | 20.6 | 8 | 14.8 |

| Superior arcuate + inferior altitudinal | 3 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Superior arcuate + inferior altitudinal + central scotoma | 27 | 15.4 | 12 | 22.2 |

| Superior altitudinal + inferior arcuate | 3 | 1.7 | 2 | 3.7 |

| Superior altitudinal + inferior arcuate + central scotoma | 11 | 6.3 | 8 | 14.8 |

| Superior + inferior altitudinal | 12 | 6.9 | 1 | 1.9 |

| Diffuse depression | 27 | 15.4 | 3 | 5.6 |

| Absolute defect | 24 | 13.7 | 6 | 11.1 |

| Other: isolated defect | 2 | 1.1 | 1 | 1.9 |

| Other: 2 or more defects | 15 | 8.6 | 9 | 16.7 |

| Total | 175 | 100 | 54 | 100 |

Relationship Between Severity of Defect and Global Indices of Visual Function

The severity of field defects for the study eye was compared to global indices of visual field abnormality provided by the HVF. Both the mean deviation and the corrected pattern standard deviation (CPSD) were included in the evaluation (Table 10). Fields may have had more than one defect with differing severity (eg, mild superior arcuate and severe inferior altitudinal). Therefore, visual fields were divided into normal, mild only, mild and moderate, moderate only, mild and severe, mild-moderate and severe, moderate and severe, and severe only. The average mean deviation for randomized study eyes was −21.47, compared to −14.51 for nonrandomized study eyes, and −4.70 for fellow eyes without optic neuropathy. Corrected pattern standard deviation was largest for the observation group, averaging 10.18, compared to 7.03 for the randomized group and 3.50 for the fellow eye group without optic neuropathy. Across all categories, the mean deviations tended to decline with increasing severity of field defect. However, the decline was not monotonic for any of the categories. Corrected pattern standard deviation tended to be small for mild-only and severe-only disease but did not differ systematically for the other categories of severity.

Table 10.

Global indices at baseline by severity of defect and patient group and eye

| Categorization of eyes for baseline paper |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study eye: randomized |

Study eye: observation |

Fellow eye: no optic neuropathy |

|||||||||||||

| Mean deviation |

Corrected pattern SD |

Mean deviation |

Corrected pattern SD |

Mean deviation |

Corrected pattern SD |

||||||||||

| Defect | n | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Normal field | 1 | −0.56 | . | 0.41 | . | 1 | −0.60 | . | 2.55 | 47 | −0.05 | 0.77 | 1.06 | 0.77 | |

| Mild only | 3 | −7.93 | 5.74 | 4.01 | 2.82 | 15 | −3.83 | 2.57 | 3.80 | 2.39 | 162 | −3.19 | 2.26 | 2.54 | 1.65 |

| Mild and moderate | 22 | −9.64 | 4.31 | 8.51 | 3.12 | 23 | −10.08 | 3.93 | 8.53 | 3.22 | 39 | −6.60 | 2.38 | 5.17 | 2.12 |

| Moderate only | 9 | −14.79 | 3.69 | 9.78 | 2.63 | 14 | −9.99 | 4.64 | 9.24 | 3.72 | 35 | −11.39 | 3.96 | 7.39 | 2.42 |

| Mild and severe | 62 | −22.29 | 3.85 | 8.91 | 2.84 | 34 | −19.19 | 4.36 | 11.38 | 3.07 | 9 | −17.16 | 6.01 | 10.05 | 1.97 |

| Mild, moderate, and severe | 53 | −23.69 | 8.51 | 6.06 | 5.10 | 6 | −14.37 | 4.86 | 11.58 | 2.78 | 1 | −5.17 | - | 4.12 | - |

| Moderate and severe | 18 | −14.40 | 6.23 | 11.89 | 2.79 | 34 | −16.15 | 3.79 | 13.53 | 2.36 | 1 | −13.00 | - | 13.11 | - |

| Severe only | 61 | −27.06 | 5.68 | 3.83 | 3.38 | 20 | −20.80 | 7.90 | 9.72 | 5.15 | 3 | −16.24 | 14.59 | 3.39 | 3.52 |

| Total | 229 | −21.47 | 8.22 | 7.03 | 4.41 | 147 | −14.51 | 7.11 | 10.18 | 4.31 | 297* | −4.70 | 4.96 | 3.50 | 2.87 |

*Total is not 301 because four patients have missing severity.

Relationship Between Visual Acuity and Category of Visual Field Defect

Analysis was performed to evaluate the visual acuity at baseline for the various patterns of field defects. For the 374 study eyes (Tables 11A and B), visual acuity was almost equally distributed for visual acuity 20/10 to <20/64 , 133 eyes; 20/64 to <20/200, 108 eyes; and 20/200 or worse, 133 eyes. Visual acuity better than 20/64 was associated with isolated superior arcuate in three eyes (100% of all superior arcuate defects), inferior arcuate defects in 15 eyes (88.2%), combined superior and inferior arcuate defects in 41 eyes (80.4%), and combined superior arcuate with inferior altitudinal defects in 13 eyes (65%). Visual acuity 20/200 or worse was found most frequently for 24 eyes with diffuse depression (77.4%) or 29 eyes with absolute defects (96.7%). Other patterns of field defects, including those with central scotomas, were divided between the 20/64 to 20/200 and the 20/200 and worse categories. Intermediate visual loss of 20/64 to 20/200 was most characteristic of the following visual field patterns: superior and inferior arcuate defects with paracentral scotoma in 10 eyes (50.0%) and central scotoma in 29 eyes (53.7%). For the fellow eye without optic neuropathy (Table 11C), 284 eyes (95.6%) had visual acuity of 20/64 or better. Acuity of 20/64 to 20/200 was noted in eight eyes (2.7%), and acuity worse than 20/200 in four eyes (1.4%).

Table 11a.

Visual acuity at baseline by category of field defect, study eye

| Visual acuity at baseline |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20/10 to <20/64 | 20/64 to <20/200 | 20/200 and worse | total | |||||

| Pattern | n | Row % | n | Row % | n | Row % | n | Row % |

| Normal | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 100.0 |

| Superior arcuate isolated | 3 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 100.0 |

| Inferior arcuate isolated | 15 | 88.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 11.8 | 17 | 100.0 |

| Superior + inferior arcuate | 41 | 80.4 | 8 | 15.7 | 2 | 3.9 | 51 | 100.0 |

| Superior + inferior arcuate + paracentral scotoma | 9 | 45.0 | 10 | 50.0 | 1 | 5.0 | 20 | 100.0 |

| Superior + inferior arcuate + central scotoma | 10 | 18.5 | 29 | 53.7 | 15 | 27.8 | 54 | 100.0 |

| Superior arcuate + inferior altitudinal | 13 | 65.0 | 4 | 20.0 | 3 | 15.0 | 20 | 100.0 |

| Superior arcuate + inferior altitudinal + central scotoma | 6 | 13.0 | 18 | 39.1 | 22 | 47.8 | 46 | 100.0 |

| Superior altitudinal + inferior arcuate | 6 | 54.5 | 5 | 45.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 100.0 |

| Superior altitudinal + inferior arcuate + central scotoma | 3 | 13.6 | 6 | 27.3 | 13 | 59.1 | 22 | 100.0 |

| Superior + inferior altitudinal | 4 | 22.2 | 5 | 27.8 | 9 | 50.0 | 18 | 100.0 |

| Diffuse depression | 1 | 3.2 | 6 | 19.4 | 24 | 77.4 | 31 | 100.0 |

| Absolute defect | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 3.3 | 29 | 96.7 | 30 | 100.0 |

| Other: isolated defect | 4 | 57.1 | 1 | 14.3 | 2 | 28.6 | 7 | 100.0 |

| Other: 2 or more defects | 17 | 40.5 | 14 | 33.3 | 11 | 26.2 | 42 | 100.0 |

| Total | 133 | 35.6 | 108 | 28.9 | 133 | 35.6 | 374 | 100.0 |

Table 11b.

Visual acuity at baseline by further characterization of field defects, study eye

| Visual acuity at baseline |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20/10 to <20/64 | 20/64 to <20/200 | 20/200 and worse | Total | ||||||

| Pattern (isolated or in combination) | n | Row % | n | Row % | n | Row % | n | Row % | |

| Any superior defect | No | 29 | 28.2 | 15 | 14.6 | 59 | 57.3 | 103 | 100.0 |

| Yes | 111 | 38.5 | 94 | 32.6 | 83 | 28.8 | 288 | 100.0 | |

| Any inferior defect | No | 9 | 11.8 | 11 | 14.5 | 56 | 73.7 | 76 | 100.0 |

| Yes | 133 | 42.0 | 98 | 30.9 | 86 | 27.1 | 317 | 100.0 | |

| Any superior or inferior defect | No | 5 | 7.4 | 8 | 11.8 | 55 | 80.9 | 68 | 100.0 |

| Yes | 137 | 42.2 | 101 | 31.1 | 87 | 26.8 | 325 | 100.0 | |

| Any scotoma | No | 89 | 46.8 | 32 | 16.8 | 69 | 36.3 | 190 | 100.0 |

| Yes | 44 | 23.9 | 76 | 41.3 | 64 | 34.8 | 184 | 100.0 | |

| Any diffuse defect | No | 132 | 42.2 | 101 | 32.3 | 80 | 25.6 | 313 | 100.0 |

| Yes | 1 | 1.6 | 7 | 11.5 | 53 | 86.9 | 61 | 100.0 | |

Table 11c.

Visual acuity at baseline by further characterization of field defects, fellow eye: no optic neuropathy

| Visual acuity at baseline |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20/10 to <20/64 | 20/64 to <20/200 | 20/200 and worse | Total | ||||||

| Pattern (isolated or in combination) | n | Row % | n | Row % | n | Row % | n | Row % | |

| Any superior defect | No | 78 | 98.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.3 | 79 | 100.0 |

| Yes | 219 | 95.2 | 8 | 3.5 | 3 | 1.3 | 230 | 100.0 | |

| Any inferior defect | No | 91 | 98.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.1 | 92 | 100.0 |

| Yes | 210 | 95.0 | 8 | 3.6 | 3 | 1.4 | 221 | 100.0 | |

| Any superior or | No | 56 | 98.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.8 | 57 | 100.0 |

| inferior defect | Yes | 246 | 95.7 | 8 | 3.1 | 3 | 1.2 | 257 | 100.0 |

| Any scotoma | No | 273 | 96.8 | 6 | 2.1 | 3 | 1.1 | 282 | 100.0 |

| Yes | 15 | 83.3 | 2 | 11.1 | 1 | 5.6 | 18 | 100.0 | |

| Any diffuse defect | No | 284 | 96.3 | 8 | 2.7 | 3 | 1.0 | 295 | 100.0 |

| Yes | 4 | 80.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 5 | 100.0 | |

As shown in Table 12A, for the study eye mild defects were associated with good acuity in 15 of 18 eyes (83.3%), whereas severe defects were associated with good acuity in 81 (28.3%) of 286 eyes. In the fellow eye without optic neuropathy (Table 12B), there were only 14 eyes with severe defects. However, of the 14 cases for which a severe field defect was present, visual acuity was still between 20/10 and 20/64 in 11 (78.6%) and 20/200 or worse in the remainder.

Table 12a.

Visual acuity at baseline by worst defect severity, study eye

| Visual acuity at baseline |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20/10 to <20/64 | 20/64 to <20/200 | 20/200 and worse | Total | ||||||

| Severity | n | Row % | n | Row % | n | Row % | n | Row % | |

| Worst | Normal field | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 100.0 |

| Mild | 15 | 83.3 | 1 | 5.6 | 2 | 11.1 | 18 | 100.0 | |

| Moderate | 36 | 52.9 | 22 | 32.4 | 10 | 14.7 | 68 | 100.0 | |

| Severe | 81 | 28.3 | 84 | 29.4 | 121 | 42.3 | 286 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 133 | 35.6 | 108 | 28.9 | 133 | 35.6 | 374 | 100.0 | |

Table 12b.

Visual acuity at baseline by worst defect severity, fellow eye: no optic neuropathy

| Visual acuity at baseline |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20/10 to <20/64 | 20/64 to <20/200 | 20/200 and worse | Total | ||||||

| Severity | n | Row % | n | Row % | n | Row % | n | Row % | |

| Worst | Normal field | 47 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 47 | 100.0 |

| Mild | 157 | 97.5 | 4 | 2.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 161 | 100.0 | |

| Moderate | 69 | 93.2 | 4 | 5.4 | 1 | 1.4 | 74 | 100.0 | |

| Severe | 11 | 78.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 21.4 | 14 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 284 | 95.9 | 8 | 2.7 | 4 | 1.4 | 296 | 100.0 | |

Relationship of Age to Pattern and Severity of Visual Field Defect

The relationship of age to the pattern and severity of visual field defect was evaluated for patients over 65 years and compared to those 65 years or under. Results are summarized in Table 13.

Table 13a.

Category of field defect at baseline by risk factor, study eye

| Age |

Hx of 1+ vascular conditions at baseline |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥65 | > 65 | No | Yes | |||||

| Pattern | n | Col % | n | Col % | n | Col % | n | Col % |

| Normal | 2 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Superior arcuate isolated | 2 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.9 |

| Inferior arcuate isolated | 11 | 7.1 | 6 | 2.7 | 9 | 5.8 | 8 | 3.6 |

| Superior + inferior arcuate | 28 | 17.9 | 23 | 10.5 | 23 | 14.9 | 28 | 12.6 |

| Superior + inferior arcuate + paracentral scotoma | 7 | 4.5 | 14 | 6.4 | 10 | 6.5 | 11 | 5.0 |

| Superior + inferior arcuate + central scotoma | 21 | 13.5 | 33 | 15.0 | 23 | 14.9 | 31 | 14.0 |

| Superior arcuate + inferior altitudinal | 8 | 5.1 | 12 | 5.5 | 11 | 7.1 | 9 | 4.1 |

| Superior arcuate + inferior altitudinal + central scotoma | 12 | 7.7 | 35 | 15.9 | 17 | 11.0 | 30 | 13.5 |

| Superior altitudinal + inferior arcuate | 5 | 3.2 | 6 | 2.7 | 5 | 3.2 | 6 | 2.7 |

| Superior altitudinal + inferior arcuate + central scotoma | 12 | 7.7 | 10 | 4.5 | 11 | 7.1 | 11 | 5.0 |

| Superior + inferior altitudinal | 3 | 1.9 | 15 | 6.8 | 4 | 2.6 | 14 | 6.3 |

| Diffuse depression | 9 | 5.8 | 22 | 10.0 | 10 | 6.5 | 21 | 9.5 |

| Absolute defect | 7 | 4.5 | 23 | 10.5 | 9 | 5.8 | 21 | 9.5 |

| Other: isolated defect | 6 | 3.8 | 1 | 0.5 | 2 | 1.3 | 5 | 2.3 |

| Other: 2 or more defects | 23 | 14.7 | 19 | 8.6 | 18 | 11.7 | 24 | 10.8 |

| Total | 156 | 100 | 220 | 100 | 154 | 100 | 222 | 100 |

Based on a total of 220 patients aged 65 or over and 156 patients under age 65, combined superior and inferior arcuate defects were the most frequently encountered (n = 28) in the under 65 age group for the study eye (17.9%). They were less common (n = 23) in the 65 or over age group (10.5%). Second most common in the younger age group were the 21 eyes with superior and inferior arcuate defects with central scotoma (13.5%), but this did not differ in frequency much from the 33 eyes in the older age group (15%). The most frequently encountered pattern of defect in the older age group was a superior arcuate and inferior altitudinal defect with central scotoma in 35 eyes (15.9%). Only 12 eyes (7.7%) of the under age 65 group demonstrated a similar defect. As shown in Table 13B, evaluating study eyes based upon the worst severity of field defects encountered within a single visual field demonstrated that only four eyes in patients 65 or over (1.8%) had mild defects compared to 14 eyes in the under 65 group (9%). Conversely, there were 108 eyes (69.2%) in the under age 65 group manifesting severe field defect compared to 180 eyes (81.8%) in the 65 or over age group. This pattern was statistically significant (Kendall’s tau-b = 3.041, P = .002).

Table 13b.

Worst defect severity at baseline by risk factors, study eye

| Age |

Hx of 1+ vascular conditions at baseline |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥65 | > 65 | No | Yes | ||||||

| Severity | n | Col % | n | Col % | n | Col % | n | Col % | |

| Worst | Normal field | 2 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Mild | 14 | 9.0 | 4 | 1.8 | 5 | 3.2 | 13 | 5.9 | |

| Moderate | 32 | 20.5 | 36 | 16.4 | 29 | 18.8 | 39 | 17.6 | |

| Severe | 108 | 69.2 | 180 | 81.8 | 119 | 77.3 | 169 | 76.1 | |

| Total | 156 | 100 | 220 | 100 | 154 | 100 | 222 | 100 | |

In the fellow eye without optic neuropathy (Table 13C), a few differences in the frequency of pattern defect were noted related to age. Normal fields were found in 29 eyes (21.6%) in the younger age group compared to 18 eyes in the 65 or over age group (10.8%). The frequency of other types of field defects did not vary based upon the age range in which they fell. Greatest severity at the moderate level (Table 13D) was present in 49 eyes in the older age group (29.7%) but in only 25 eyes in the younger age group (18.9%). The differences in severity of field defects based upon age were statistically significant (Kendall’s tau-b = 3.313, P = .001).

Table 13c.

Category of field defect at baseline by risk factor, fellow eye: optic neuropathy, no optic neuropathy

| Age |

Hx of 1+ vascular conditions at baseline |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <65 | > 65 | No | Yes | |||||

| Pattern | n | Col % | n | Col % | n | Col % | n | Col % |

| Normal | 29 | 21.6 | 18 | 10.8 | 25 | 20.7 | 22 | 12.2 |

| Superior arcuate isolated | 15 | 11.2 | 20 | 12.0 | 14 | 11.6 | 21 | 11.7 |

| Inferior arcuate isolated | 12 | 9.0 | 8 | 4.8 | 10 | 8.3 | 10 | 5.6 |

| Superior + inferior arcuate | 67 | 50.0 | 102 | 61.1 | 61 | 50.4 | 108 | 60.0 |

| Superior + inferior arcuate + paracentral scotoma | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1.8 | 1 | 0.8 | 2 | 1.1 |

| Superior + inferior arcuate + central scotoma | 2 | 1.5 | 5 | 3.0 | 2 | 1.7 | 5 | 2.8 |

| Superior arcuate + inferior altitudinal | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Superior altitudinal + inferior arcuate | 2 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.6 | 2 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Superior altitudinal + inferior arcuate + central scotoma | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Superior + inferior altitudinal | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.1 |

| Diffuse depression | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other: isolated defect | 2 | 1.5 | 3 | 1.8 | 3 | 2.5 | 2 | 1.1 |

| Other: 2 or more defects | 5 | 3.7 | 2 | 1.2 | 2 | 1.7 | 5 | 2.8 |

| Total | 134 | 100 | 167 | 100 | 121 | 100 | 180 | 100 |

Table 13d.

Worst defect severity baseline by risk factors, fellow eye: optic neuropathy, no optic neuropathy

| Age |

Hx of 1+ vascular conditions at baseline |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <65 | > 65 | No | Yes | ||||||

| Severity | n | Col % | n | Col % | n | Col % | n | Col % | |

| Worst | Normal field | 29 | 22.0 | 18 | 10.9 | 25 | 20.8 | 22 | 12.4 |

| Mild | 74 | 56.1 | 88 | 53.3 | 65 | 54.2 | 97 | 54.8 | |

| Moderate | 25 | 18.9 | 49 | 29.7 | 21 | 17.5 | 53 | 29.9 | |

| Severe | 4 | 3.0 | 10 | 6.1 | 9 | 7.5 | 5 | 2.8 | |

| Total | 132 | 100 | 165 | 100 | 120 | 100 | 177 | 100 | |

Relationship of Vascular Conditions to Pattern and Severity of Visual Field Defect

Several risk factors were evaluated, including history of hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, angina, and transient ischemic attack. No differences in pattern were noted among the various vascular risk factors, and the numbers for some categories were small; therefore, these risks were combined. Results are summarized in Table 13.

The effect of vascular conditions at baseline on pattern of visual field in the study eye was assessed (Table 13A). No important differences were found. Patients with vascular conditions at baseline numbered 222, and those without numbered 154. The most commonly encountered defects for eyes with or without vascular conditions were superior and inferior arcuate defects (n = 28 with, 23 without), superior and inferior arcuate defects with central scotoma (n = 31 with, 23 without), and superior arcuate and inferior altitudinal defects with central scotoma (n = 30 with, 17 without). The percentage of total field patterns for any one pattern ranged from 11.0% to 14.9%. In evaluating greatest magnitude of visual field defect (Table 13B), the distribution did not appear to differ between the group with or without vascular conditions at baseline (Kendall’s tau-b = −.367, P = .714). In the vascular category, 169 of 222 eyes (76.1%) had a greatest magnitude of visual field defect that was severe, similar to the same severity group in the nonvascular category of 119 of 154 eyes (77.3%).

The effect of vascular conditions at baseline on pattern of visual field in the nonstudy eye without optic neuropathy was assessed as well (Table 13C). In the vasculopathy group of 180 patients, normal fields were found in 22 (12.2%). In the nonvasculopathy group of 121 patients, normal fields were found in 25 (20.7%). The frequency of other types of field defects did not vary based upon the presence or absence of vasculopathic risk factors. Of the 177 eyes with vascular conditions at baseline, 53 (29.9%) had a greatest magnitude of visual field defect that was moderate. In contrast, of the 120 eyes with no vascular conditions at baseline, 21 (17.5%) had a greatest magnitude of visual field defect that was moderate (Table 13D). In the category of greatest magnitude of field defect of severe, only five eyes (2.8%) were in the vascular condition group compared to nine eyes (7.5%) in the no vascular condition group. However, there was no statistically significant difference in overall distribution of field defect magnitude between the two groups ( Kendall’s tau-b = .095, P = .087).

Longitudinal Follow-up: Comparing 6-Month to Baseline Visual Fields

Overall Description

There were 605 eyes with visual fields performed at both the baseline and the 6-month visit. Of these, 571 had data at both time points and had foveal sensitivity. After unreliable fields were excluded, 559 eyes were available for longitudinal analysis. Of these, 203 (36.3%) were randomized study eyes, 75 (13.4%) were nonrandomized study eyes, 57 (10.2%) were fellow eyes with optic neuropathy, and 224 (40.1%) were fellow eyes without optic neuropathy.

The SFs at baseline and at the 6-month follow-up field were compared. For all 559 eyes, the mean SF at baseline was 2.43 (1.45 SD) compared to 2.27 (1.49 SD) at 6 months. For the randomized eyes, mean SF at baseline was 2.58 (1.80 SD), and at 6 months it was 2.57 (1.78 SD). For the nonrandomized study eyes, the mean SF was 2.56 (1.24 SD) at baseline and 2.60 (1.35 SD) at 6 months. For fellow eyes without optic neuropathy, the mean SF at baseline was 2.16 (0.89 SD) and at 6 months, 1.81 (0.78 SD).

Visual Field Changes Between 6-Month and Baseline Visits for Randomized Study Eyes

In evaluating the 203 randomized study eyes, the pattern of defect in the superior and inferior visual fields did not change significantly between baseline and 6-month follow-up (Table 14A). For superior visual fields, the Stuart-Maxwell test of marginal homogeneity had a chi-square of 3.40, P = .18; for inferior visual fields the chi-square was 0.88, P = .64. A statistically significant change in central field was noted for randomized eyes with chi-square of 11.43, P = .003. However, there was not a consistent direction of change. For instance, of 160 central field defects at baseline, 29 (18.1%) changed to neither a central nor a paracentral defect and 14 (8.8%) changed to paracentral defects. Of 28 eyes with neither central nor paracentral defects at baseline, 14 (50.0%) developed central defects.

Table 14a.

Frequency of visual field defects at baseline and at 6-month follow-up: randomized eyes

| Superior visual field |

Inferior visual field |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-month follow-up field | 6-month follow-up field | ||||||||

| Baseline field | No defect | Arcuate | Altitudinal | Total | Baseline field | No defect | Arcuate | Altitudinal | Total |

| No defect (n) | 3 | 9 | 1 | 13 | No defect (n) | 3 | 3 | 1 | 7 |

| Row % | 23.08 | 69.23 | 7.69 | 100 | Row % | 42.86 | 42.86 | 14.29 | 100 |

| Column % | 27.27 | 9.38 | 1.04 | 6.40 | Column % | 42.86 | 3.37 | 0.93 | 3.45 |

| Arcuate | 8 | 83 | 10 | 101 | Arcuate | 3 | 70 | 11 | 84 |

| Row % | 7.92 | 82.18 | 9.90 | 100 | Row % | 3.57 | 83.33 | 13.10 | 100 |

| Column % | 72.73 | 86.46 | 10.42 | 49.75 | Column % | 42.86 | 78.65 | 10.28 | 41.38 |

| Altitudinal | 0 | 4 | 85 | 89 | Altitudinal | 1 | 16 | 95 | 112 |

| Row % | 0.00 | 4.49 | 95.51 | 100 | Row % | 0.89 | 14.29 | 84.82 | 100 |

| Column % | 0.00 | 4.17 | 88.54 | 43.84 | Column % | 14.29 | 17.98 | 88.79 | 55.17 |

| Total | 11 | 96 | 96 | 203 | Total | 7 | 89 | 107 | 203 |

| Row % | 5.42 | 47.29 | 47.29 | 100 | Row % | 3.45 | 43.84 | 52.71 | 100 |

| Column % | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | Column % | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Marginal homogeneity (Stuart-Maxwell) | chi-square | df | P | Marginal homogeneity (Stuart-Maxwell) | chi-square | df | P | ||

| 3.40 | 2 | .18 | 0.88 | 2 | .64 | ||||

For those randomized eyes that maintained the same pattern of defect at 6 months and at baseline, the severity of defect was compared (Table 15A). Superior arcuate defect severity did not vary (t = −0.098, P = .92) in the interval with a mean loss for 83 eyes of 14.71 dB (7.86 SD) at baseline and of 14.63 dB (8.01 SD) at 6 months. However, superior altitudinal defects for 85 eyes did improve significantly (t = −2.24, P = .028).

Table 15a.

Severity of visual field defect at baseline and 6 months, for eyes with same defect at both visits: randomized eyes

| Superior arcuate | Inferior arcuate | ||||||||

| Examination | n | mean | SE | SD | Examination | n | mean | SE | SD |

| 6 month | 83 | 14.63 | 0.88 | 8.01 | 6 month | 70 | 19.20 | 1.01 | 8.46 |

| baseline | 83 | 14.71 | 0.86 | 7.86 | baseline | 70 | 18.42 | 1.03 | 8.66 |

| difference | 83 | −0.79 | 0.81 | 7.38 | difference | 70 | 0.78 | 0.72 | 6.00 |

| Paired t test | t | P | Paired t test | t | P | ||||

| −0.098 | .92 | 1.09 | .28 | ||||||

| Superior altitudinal | Inferior altitudinal | ||||||||

| Examination | n | mean | SE | SD | Examination | n | mean | SE | SD |

| 6 month | 85 | 25.49 | 0.62 | 5.67 | 6 month | 95 | 27.85 | 0.44 | 4.28 |

| baseline | 85 | 26.63 | 0.55 | 5.03 | baseline | 95 | 28.84 | 0.34 | 3.35 |

| difference | 85 | −1.14 | 0.51 | 4.72 | difference | 95 | −0.99 | 0.38 | 3.68 |

| Paired t test | t | P | Paired t test | t | P | ||||

| −2.24 | .028 | −2.63 | .01 | ||||||

| Paracentral scotoma | Central scotoma | ||||||||

| Examination | n | mean | SE | SD | Examination | n | mean | SE | SD |

| 6 month | 9 | 16.72 | 2.17 | 6.51 | 6 month | 117 | 5.37 | 0.79 | 8.56 |

| baseline | 9 | 18.81 | 1.54 | 4.62 | baseline | 117 | 6.17 | 0.77 | 8.34 |

| difference | 9 | −2.09 | 1.99 | 5.97 | difference | 117 | −0.80 | 0.97 | 10.54 |

| Paired t test | t | P | Paired t test | t | P | ||||

| −1.05 | .32 | −0.82 | .41 | ||||||

Inferior field changes mirrored the superior field changes. For inferior arcuate defects of 70 eyes, the mean depression at baseline was 18.42 dB (8.66 SD) compared to a mean sensitivity loss of 19.20 (8.26 SD) at 6 months. The difference was not significant (t = 1.09, P = .28). For inferior altitudinal defects, the baseline mean sensitivity loss was 28.84 dB (3.35 SD) compared to a 6-month sensitivity loss of 27.84 (4.28.SD). The mean difference of −.99 (3.68 SD) was statistically significant (t = −2.63, P = .01). Paracentral visual field defects did not differ in severity between baseline and 6 months for randomized study eyes (t = −1.05, P = .32), nor did central defects (t = −0.82, P = .41). Of nine paracentral scotomas, the mean depression was 18.81 dB (4.62 SD) at baseline compared to 16.72 (6.51 SD) at 6 months. Of 117 central scotomas, the mean depression was 6.17 dB (8.34 SD) at baseline compared to 5.37 (8.56 SD) at 6 months.

Visual Field Changes Between 6-Month and Baseline Visits for Nonrandomized Study Eyes

In evaluating the 75 nonrandomized study eyes, the pattern of defect in the superior and inferior visual fields did not change significantly between baseline and 6-month follow-up (Table 14B). For superior visual fields, the Stuart-Maxwell test of marginal homogeneity had a chi-square of 0.55, P =.76; for inferior visual fields the chi-square was 3.67, P = .16. A statistically significant change in central field was noted for nonrandomized eyes with chi-square of 6.03, P = .05. The numbers within each cell of the 3×3 table were too small to consider the direction of change.

Table 14b.

Frequency of visual field defects at baseline and at 6-month follow-up: nonrandomized eyes

| Superior visual field |

Inferior visual field |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-month follow-up field | 6-month follow-up field | ||||||||

| Vaseline field | No defect | Arcuate | Altitudinal | Total | Baseline field | No defect | Arcuate | Altitudinal | Total |

| No defect (n) | 8 | 5 | 2 | 15 | No defect (n) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Row % | 53.33 | 33.33 | 13.33 | 100 | Row % | 100.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 100 |

| Column % | 44.44 | 10.87 | 18.18 | 20.00 | Column % | 50.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 |

| Arcuate | 9 | 36 | 3 | 48 | Arcuate | 3 | 51 | 4 | 58 |

| Row % | 18.75 | 75.00 | 6.25 | 100 | Row % | 5.17 | 87.93 | 6.90 | 100 |

| Column % | 50.00 | 78.26 | 27.27 | 64.00 | Column % | 50.00 | 96.23 | 25.00 | 77.33 |

| Altitudinal | 1 | 5 | 6 | 12 | Altitudinal | 0 | 2 | 12 | 14 |

| Row % | 8.33 | 41.67 | 50.00 | 100 | Row % | 0.00 | 14.29 | 85.71 | 100 |

| Column % | 5.56 | 10.87 | 54.55 | 16.00 | Column % | 0.00 | 3.77 | 75.00 | 18.67 |

| Total | 18 | 46 | 11 | 75 | Total | 6 | 53 | 16 | 75 |

| Row % | 24.00 | 61.33 | 14.67 | 100 | Row % | 8.00 | 70.67 | 21.33 | 100 |

| Column % | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | Column % | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Marginal homogeneity (Stuart-Maxwell) | chi-square | df | P | Marginal homogeneity (Stuart-Maxwell) | chi-square | df | P | ||

| 0.55 | 2 | .76 | 3.67 | 2 | .16 | ||||

For those nonrandomized eyes that maintained the same pattern of defect at 6 months and at baseline, the severity of defect was compared (Table 15B). Superior arcuate defect severity worsened (t = 2.98, P = .005) in the interval with a mean loss for 36 eyes at baseline of 11.85 dB (6.73 SD) and at 6 months of 15.68 dB (8.05 SD). However, superior altitudinal defects did not change significantly (t = −2.07, P = .093), with a mean at baseline of 23.89 dB (7.75 SD) and at 6 months of 22.02 dB (7.63 SD). Inferior altitudinal defects improved (t = −2.83, P = .017). For inferior arcuate defects of 51 eyes, the mean depression at baseline was 18.29 dB (7.81 SD) compared to a mean sensitivity loss of 18.41 (7.97 SD) at 6 months. The difference was not significant (t = 0.13, P = .90). For inferior altitudinal defects, the baseline mean sensitivity loss for 12 eyes was 26.69 dB (5.50 SD) compared to a 6-month sensitivity loss of 25.13 (5.89 SD). The mean difference of −1.57 (1.92 SD) was statistically significant (P = −2.83, P = .016). Paracentral visual field defects improved in severity between baseline and 6 months for 10 nonrandomized study eyes (t = −2.40, P = .04), but 4 central defects did not (t = 1.98, P = .14). Of 10 paracentral scotomas, the mean depression was 14.55 dB (7.08 SD) at baseline compared to 12.98 (6.95 SD) at 6 months. Of four central scotomas the mean depression was 12.25 dB (14.43 SD) at baseline compared to 21.00 (12.06 SD) at 6 months.

Table 15b.

Severity of visual field defect at baseline and 6 months, for eyes with same defect at both visits: nonrandomized eyes

| Superior arcuate | Inferior arcuate | ||||||||

| Examination | n | mean | SE | SD | Examination | n | mean | SE | SD |

| 6 month | 36 | 15.68 | 1.34 | 8.05 | 6 month | 51 | 18.41 | 1.12 | 7.97 |

| Baseline | 36 | 11.85 | 1.12 | 6.73 | Baseline | 51 | 18.29 | 1.09 | 7.81 |

| Difference | 36 | 3.83 | 1.28 | 7.7 | Difference | 51 | 0.12 | 1.00 | 7.12 |

| Paired t test | t | P | Paired t test | t | P | ||||

| 2.98 | 0.005 | 0.13 | 0.90 | ||||||

| Superior altitudinal | Inferior altitudinal | ||||||||

| Examination | n | mean | SE | SD | Examination | n | mean | SE | SD |

| 6 month | 6 | 22.02 | 3.11 | 7.63 | 6 month | 12 | 25.13 | 1.70 | 5.89 |

| Baseline | 6 | 23.89 | 3.17 | 7.75 | Baseline | 12 | 26.69 | 1.59 | 5.50 |

| Difference | 6 | −1.87 | 0.9 | 2.21 | Difference | 12 | −1.57 | 0.55 | 1.92 |

| Paired t test | t | P | Paired t test | t | P | ||||

| −2.07 | 0.093 | −2.83 | 0.016 | ||||||

| Paracentral scotoma | Central scotoma | ||||||||

| Examination | n | mean | SE | SD | Examination | n | mean | SE | SD |

| 6 month | 10 | 12.98 | 2.2 | 6.95 | 6 month | 4 | 21 | 6.03 | 12.06 |

| Baseline | 10 | 14.55 | 2.24 | 7.08 | Baseline | 4 | 12.25 | 7.22 | 14.43 |

| Difference | 10 | −1.57 | 0.65 | 2.06 | Difference | 4 | 8.75 | 4.42 | 8.85 |

| Paired t test | t | P | Paired t test | t | P | ||||

| −2.4 | 0.04 | 1.98 | 0.14 | ||||||

Visual Field Changes Between 6-Month and Baseline Visits for Fellow Eyes Without Optic Neuropathy

In evaluating the 224 fellow eyes without optic neuropathy, there was a significant change in pattern of defect in the superior and inferior visual fields between baseline and 6-month follow-up (Table 14C). For superior visual fields, the Stuart-Maxwell test of marginal homogeneity had a chi-square of 27.02, P < .0001; for inferior visual fields the chi-square was 27.60, P < .0001. Central fields were too few to be analyzed. The direction of change for both upper and lower fields was primarily that of an arcuate defect at baseline changing to no defect at the 6-month visit, seen for 27.4% of 164 eyes with a superior arucate defect at baseline and for 29.9% of 154 eyes with an inferior arcuate defect at baseline.

Table 14c.

Frequency of visual field defects at baseline and at 6-month follow-up: fellow eyes without optic neuropathy

| Superior visual field |

Inferior visual field |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-month follow-up field | 6-month follow-up field | ||||||||||

| Baseline field | No defect | Arcuate | Altitudinal | Other | Total | Baseline field | No defect | Arcuate | Altitudinal | Other | Total |

| No defect (n) | 44 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 53 | No defect (n) | 51 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 64 |

| Row % | 83.02 | 15.09 | 0.00 | 1.89 | 100 | Row % | 79.69 | 14.06 | 1.56 | 4.69 | 100 |

| Column % | 48.89 | 6.45 | 0.00 | 16.67 | 23.66 | Column % | 51.00 | 7.89 | 25.00 | 50.00 | 28.57 |

| Arcuate | 45 | 113 | 1 | 5 | 164 | Arcuate | 46 | 104 | 1 | 3 | 154 |

| Row % | 27.44 | 68.9 | 0.61 | 3.05 | 100 | Row % | 29.87 | 67.53 | 0.65 | 1.95 | 100 |

| Column % | 50 | 91.13 | 25.00 | 83.33 | 73.21 | Column % | 46.00 | 91.23 | 25.00 | 50.00 | 68.75 |

| Altitudinal | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | Altitudinal | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Row % | 0.00 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 100 | Row % | 0.00 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 100 |

| Column % | 0.00 | 0.00 | 75.00 | 0.00 | 1.34 | Column % | 0.00 | 0.00 | 50.00 | 0.00 | 0.89 |

| Other defect | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | Other defect | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Row % | 25 | 75 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 100 | Row % | 75.00 | 25.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 100 |

| Column % | 1.11 | 2.42 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.79 | Column % | 3.00 | 0.88 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.79 |

| Total | 90 | 124 | 4 | 6 | 224 | Total | 100 | 114 | 4 | 6 | 224 |

| Row % | 40.18 | 55.36 | 1.79 | 2.68 | 100 | Row % | 44.64 | 50.89 | 1.79 | 2.68 | 100 |

| Column % | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | Column % | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Marginal homogeneity (Stuart-Maxwell) | chi-square | df | P | Marginal homogeneity(Stuart-Maxwell) | chi-square | df | P | ||||

| 27.02 | 3 | <.0001 | 27.6 | 3 | <.0001 | ||||||

For those fellow eyes that maintained the same pattern of defect at 6 months and at baseline, the severity of defect was compared (Table 15C). Superior arcuate defect severity improved (t = −4.08, P = .0001) in the interval with a mean loss for 113 eyes at baseline of 9.63 dB (5.98 SD) and at 6 months of 7.68 dB (5.13 SD). For inferior arcuate defects of 104 eyes, the mean depression at baseline was 9.66 dB (5.85 SD) compared to a mean sensitivity loss of 7.24 (5.36 SD) at 6 months. The difference was highly significant (t = −4.78, P < .0001). Altitudinal defects, paracentral scotomas, and central scotomas were few.

Table 15c.

Severity of visual field defect at baseline and 6 months, for eyes with same defect at both visits: fellow eyes without optic neuropathy

| Superior arcuate | Inferior arcuate | ||||||||

| Examination | n | mean | SE | SD | Examination | n | mean | SE | SD |

| 6 month | 113 | 7.68 | 0.48 | 5.13 | 6 month | 104 | 7.24 | 0.53 | 5.36 |

| Baseline | 113 | 9.63 | 0.56 | 5.98 | Baseline | 104 | 9.66 | 0.57 | 5.85 |

| Difference | 113 | −1.95 | 0.48 | 5.08 | Difference | 104 | −2.42 | 0.51 | 5.16 |

| Paired t test | t | P | Paired t test | t | P | ||||

| −4.08 | <.0001 | −4.78 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Superior altitudinal | Inferior altitudinal | ||||||||

| Examination | n | mean | SE | SD | Examination | n | mean | SE | SD |

| 6 month | 3 | 8.31 | 3.44 | 5.96 | 6 month | 2 | 9.48 | 3.66 | 5.18 |

| Baseline | 3 | 9.99 | 1.45 | 2.51 | Baseline | 2 | 9.87 | 1.97 | 2.79 |

| Difference | 3 | −1.68 | 2.19 | 3.79 | Difference | 2 | −0.39 | 1.69 | 2.39 |

| Paracentral scotoma | Central scotoma | ||||||||

| Examination | n | mean | Examination | n | mean | SE | SD | ||

| 6 month | 1 | 11.17 | 6 month | 2 | 23.5 | 0.5 | 0.71 | ||

| Baseline | 1 | 11.33 | Baseline | 2 | 14.5 | 1.5 | 2.12 | ||

| Difference | 1 | −0.17 | Difference | 2 | 9 | 2 | 2.83 | ||

Comparison of Careful Follow-up and Surgery Treatments for Randomized Patients

Visual Field Patterns

The pattern of defects in the superior visual fields for the study eyes randomized to careful follow-up showed no difference between baseline and the 6-month visit using the Stuart-Maxwell test of marginal homogeneity (χ2 df = 1.43, P = .49). Similarly, the pattern of defects in the superior fields for the study eyes randomized to surgery showed no difference between baseline and the 6-month visit (χ2 df = 2.57, P = .28). However, seven of the eight patients who received surgery in their study eye and who had no superior defect at baseline developed either an arcuate or an altitudinal defect at 6 months. Table 16 compares the proportion of eyes that declined, stayed the same, and improved, wherein improvement is defined as changing from an altitudinal defect to an arcuate defect and decline is defined as the opposite. Using the Mantel-Haenzel extension test (M-H), no treatment effect was noted when comparing the pattern changes for the superior field described for careful follow-up and for surgery to each other (χ2 = 0.49, P = .48).

Table 16.