ABSTRACT

Objectives

To test the feasibility of human immune globulin (IG, Gamimune N, 10%) as a new treatment for endophthalmitis, the ocular tolerance, distribution, and ability of intravitreal IG to attenuate the toxic effects of Staphyloccocus aureus culture supernatant were evaluated in a rabbit model.

Methods

Effects of intravitreally injected IG were assessed histologically and with Western blot analysis performed 1 to 5 days after injection. IG reactivity to products of S aureus strain RN4220 was tested by Western blotting, using known toxins (beta hemolysin and toxic shock syndrome toxin-1) and a concentrated culture supernatant containing S aureus exotoxins (pooled toxin, PT). Endophthalmitis was induced by intravitreal PT injection. For treatment, IG and PT were mixed and injected simultaneously, or IG was injected immediately after, or 6 hours after, PT injection. PT toxicity was graded clinically and histologically over 9 days.

Results

IG persisted intravitreally at least 5 days, inducing no clinical inflammation and minimal mononuclear cell infiltration. In the endophthalmitis model, toxicity from PT was significantly reduced when IG was mixed with PT and injected simultaneously, or when IG was delivered immediately after PT. Only minimal clinically detectable reductions were observed when IG delivery was delayed 6 hours.

Conclusions

Intravitreal IG is well tolerated in the rabbit eye and attenuates the toxicity of culture supernatant containing S aureus exotoxins. Because toxin elaboration likely occurs gradually in true infection, reduced effects observed with delayed treatment in this toxin-injected model do not preclude clinical application. IG may represent a novel adjunct in endophthalmitis treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Infectious endophthalmitis can be a devastating complication of ocular surgery or trauma. Despite treatment parameters established by the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study (EVS), moderate to severe visual loss remains a common outcome.1 Infections caused by Staphyloccocus aureus, streptococcal species, and gram-negative organisms were associated with poor visual outcomes.2 S aureus constituted 10% of isolates obtained in cases of post–cataract extraction endophthalmitis.3 It also represents an infrequent but important cause of bleb-related and post-traumatic endophthalmitis.4–6

Poor visual outcomes and organism virulence appear to be strongly associated. For some bacteria, exotoxins are a critical component of virulence because they enhance bacterial propagation through host tissue.7–10 Tissue destruction in S aureus endophthalmitis results in part from the combined effects of several exotoxins.11–15

Attempts to mitigate inflammatory tissue destruction with steroids have been unsuccessful in treating experimental S aureus endophthalmitis.16–19 Improvements in the treatment of S aureus endophthalmitis may be achieved by targeting secreted toxins. Such an approach has been suggested for other bacteria.20 Experimentally, staphylococcal toxins can be neutralized with monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies.21 Clinically, intravenous immunoglobulins containing antibodies capable of neutralizing toxins have been used to help manage both staphylococcal and streptococcal toxin-mediated illnesses.22,23

The intravitreal use of toxin-specific antibodies represents a novel approach to the management of endophthalmitis. Data is presented herein demonstrating that pooled human immune globulin (IG) injected into the vitreous penetrates the retina and persists in the vitreous and retina for up to 5 days without producing clinically detectable inflammation. A “proof of principle” investigation is presented determining whether pooled human IG binds proteins in S aureus culture supernatant and two purified S aureus exotoxins, and whether IG delivered into the vitreous reduces the tissue destruction and inflammatory effects produced by an intravitreal injection of S aureus culture supernatant. The therapeutic implications of this approach to endophthalmitis and its potential limitations are discussed.

Background and Rationale

Historical Aspects

Over the past 30 years, management of infectious endophthalmitis has changed dramatically. Previously, dismal outcomes were generally associated with this condition.24,25 However, with the introduction of intravitreal antibiotic therapy, there was a marked improvement in visual prognosis.26,27 Soon after the advent of posterior vitrectomy in the early 1980s, clinical experience with this modality suggested benefit in severe cases of endophthalmitis.28–31 However, its exact role in endophthalmitis management remained controversial until 1995, when the EVS1 demonstrated improved outcome from immediate vitrectomy in acute endophthalmitis after cataract surgery or secondary intraocular lens implantation in patients with presenting visual acuity of only light perception. Nevertheless, despite undergoing vitrectomy and intravitreal antibiotic injection, 20% of such patients continued to experience permanent, severe visual acuity loss to 5/200 or worse.1

Microbiological Factors and Role of Bacterial Toxins

It has long been recognized that certain species of micro-organisms are associated with poorer prognoses, with gram-negative organisms, streptococci, enterococci, and bacillus species being the most pathogenic.27,29,31,32 Protocol measurement of outcome in the EVS allowed a rigorous comparison of relative pathogenicity among bacterial species, identifying particularly virulent groups. These organisms, primarily gram-positive organisms other than Staphylococcus epidermidis (S aureus, streptococci, enterococci, Bacillus cereus), but also gram-negatives, were associated with a statistically significant worsened clinical presentation and prognosis.2,33 The poorer outcome was observed even after management with aggressive therapy for infectious endophthalmitis, underscoring the continued importance of virulence factors. The role of such factors in mediating retinal tissue destruction and loss of function has been clearly demonstrated in studies of isogenic toxin-producing and toxin-nonproducing Enterococcus faecalis, and of other known toxin-producing organisms associated with poor prognoses, including B cereus,10,34 S aureus,11,13,14 and Streptococcus pneumoniae.35,36

Clinical Observations

In the EVS, visual acuity at presentation was the most potent independent risk factor for permanent visual loss, suggesting that intervention prior to severe visual loss was of utmost importance.1 A strong association between known toxin-producing species and poor presenting acuity was also observed,2 consistent with the role of toxins as a determinant in outcome. The time interval during which their imputed toxic effects might be reversed, retarded, or stabilized has not been determined. Clinically, during the first 24 to 48 hours after administration of intravitreal antibiotic therapy, visual acuity may worsen and inflammation may persist, even in cases successfully sterilized. The EVS protocol,37 arguably a proxy for leading authorities in the field, allowed for a substantial reduction in visual acuity after initial intravitreal antibiotic therapy prior to instituting additional measures. In some cases, visual acuity was allowed to drop to less than 5/200, in cases not already below this level, over a 36- to 60-hour interval. Thus, it can be speculated that ongoing retinal damage even after initial antibiotic therapy, from delayed bacterial killing or continued activity of toxins, might be of clinical significance. In a rabbit model of E faecalis endophthalmitis,20 toxins produced retinal damage equivalent in severity to untreated infection, even in the presence of intravitreal dexamethasone therapy and antibiotic sterilization of the vitreous cavity.

Corticosteroid Therapy in Endophthalmitis

The use of corticosteroids is both controversial and relevant, particularly as applied to endophthalmitis caused by toxin-producing organisms. Failure of intravitreal corticosteroids to moderate the tissue effects of toxins has been shown in rabbit models of endophthalmitis employing E faecalis,20 S aureus,17 and pseudomonas.38 However, a potential benefit has been observed in other studies.18,39,40 In an illuminating study using isogenic toxin-producing and toxin-nonproducing strains of E faecalis, Jett and coworkers20 showed that effects of intravitreal dexamethasone differed, depending on the degree to which toxins were produced. Moderation of inflammatory response and ERG b-wave amplitude loss was observed only in eyes infected with the toxin-nonproducing strain. In the human clinical studies, there is conflicting evidence on the benefit of intravitreal corticosteroids. No study has definitively shown an improved visual outcome when this treatment was applied to a large, possibly heterogeneous, group of endophthalmitis cases.41,42 Thus, of the microbiological factors that exist, toxin-mediated tissue destruction remains a relatively unmanaged factor in endophthalmitis.

Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis and toxins

The large number of pathogenic toxins elaborated by S aureus fall into at least two categories—hemolysins/leukocidins and pyrogenic toxin superantigens (PTSAgs). In addition, various lipases, nucleases, and proteases are produced. The hemolysins consist of four classes: alpha, beta, gamma, and delta hemolysins. Hemolysins and leukocidins are characterized by their ability to disrupt cell membranes, and most show powerful lethality when administered systemically in animal models. PTSAgs include toxic shock syndrome toxins and the family of staphylococcal enterotoxins, and are characterized by their pyrogenicity, enhancement of lethal endotoxin shock, and ability to stimulate T-lymphocyte proliferation (independent of the antigen specificity of these cells).15 The known pathogenic mechanisms and systemic manifestations have been reviewed extensively.15,43–47

Although the individual contributions of the various S aureus toxins to clinical endophthalmitis are unknown, their role as a group in mediating virulence is undisputed.7 Studies of experimental endophthalmitis infected with isogenic mutant strains deficient in the accessory gene regulator (agr) and staphylococcal accessory regulator (sar), which control expression of the PTSAgs and some hemolysins, demonstrate a clear attenuation of virulence compared to the wild strain.11,12,14 A study of a gamma-toxin-deficient strain suggested that gamma toxin has proinflammatory effects in the rabbit eye, but must be accompanied by unidentified proinflammatory molecules other than alpha-toxin, beta-toxin, or leucocidin of Panton-Valentine, since the proinflammatory strain evaluated was also deficient in these toxins.13 Gilmore and coworkers found that the alpha, beta, and gamma toxins make slight contributions to the pathogenesis of experimental S aureus endophthalmitis, but that strains with knockouts in any single gene (or even double and triple knockouts of more than a single gene) fail to reduce virulence to the level of agr/sar deficent strains (M.S. Gilmore, PhD, written communication, March 28, 2000). Therefore, the pathogenicity of S aureus toxins in endophthalmitis appears to be multifactorial.

The multifactorial character of S aureus endophthalmitis is probably shared by other infectious endophthalmitides. For example, the streptococci and gram-negative organisms, capable of causing fulminant endophthalmitis, produce numerous toxins of great systemic pathogenicity, for which ocular toxicity remains largely unexplored.44–46 Bacillus cereus produces a variety of toxins potentially damaging to the eye, including hemolysin BL, a tripartite enterotoxin with known ocular toxicity.34,48 However, no single toxin can explain its virulence,10 which appears to be multifactorial and related to both toxin production48 and organism motility.49 In contrast, knockout of only a single toxin, cytolysin, dramatically attenuates virulence in E faecalis experimental endophthalmitis.8,9,20 Because of the large microbiologic spectrum of virulent organisms encountered in clinical endophthalmitis3 and the multiplicity of toxins elaborated by various species, empiric therapy for toxin-mediated virulence would require simultaneous neutralization of many toxins of various bacterial origins. Because S aureus endophthalmitis occurs with relatively high frequency, and because its multifactorial pathogenicity is shared by other microbial forms of endophthalmitis, a model of S aureus toxin-mediated endophthalmitis appears to be a reasonable prototype for study.

Immunoglobulin Therapy for Toxin Neutralization

Previous Studies

Immunoglobulins have potential for moderating the damaging effects of bacterial toxins. Inhibition of toxic effects by toxin-specific antibodies has been demonstrated by in vitro models evaluating cytotoxicity50,51 and in animal models evaluating systemic toxicity and cardiovascular collapse.21,50 Similarly, vaccine toxoids known to stimulate antibody responses against bacterial exotoxins have a protective effect against toxic shock syndromes in experimental rabbit models.52,53 The author is aware of only a single study evaluating antitoxin antibodies in endophthalmitis. In a rabbit model of B cereus toxin-induced endophthalmitis, Beecher and coworkers34 observed a tissue protective effect of antiserum against the L2 component of hemolysin BL injected intravitreally.

Clinical Experience

Until recently, most human clinical applications of immunoglobulins in infection have consisted of intravenous administration directed at either prophylaxis or treatment of established infections using polyspecific immunoglobulin G pooled from multiple donors.54 The putative mechanism of action is immunoglobulin binding of the infectious agent specifically, facilitating opsonization, phagocytosis, lysis, and stimulation of polymorphonuclear cell function, including agglutination, chemotaxis, and oxidative metabolism.54 Clinical applications in which immunoglobulin preparations are administered specifically to neutralize microbial toxins are relatively new, representing a paradigm shift in immunoglobulin therapy for infection management. In this case, the presumed mechanism is immunoglobulin binding of toxins and not the infecting agent. Applications involve treatment of specific manifestations of toxin release (eg, toxic shock syndromes) with polyspecific intravenous IgG in conjunction with antibiotic therapy. Intravenous immunoglobulin G (IVIG) administration is associated with reduced morbidity and mortality from streptococcal toxic shock syndrome,23,55 septic shock,56,57 and, on a more anecdotal basis, staphylococcal toxin-mediated illness.22 Thus, the concept that antibodies from polyspecific, pooled immunoglobulin can be used to neutralize the toxic effects of presumably numerous bacterial toxins acting concurrently in vivo appears clinically validated. Such an approach to endophthalmitis, which may be similarly multifactorial, appears rational.

Intravenous Immunoglobulin G

Preparations of IVIG are commercially available and have been extensively characterized.58–62 One preparation available for intravenous use in the United States is Gamimune N, 10%, which has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for replacement therapy of IgG in immunodeficiency syndromes and for the treatment of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. It is isolated from pooled human plasma, is preservative-free, and consists of a 10% solution of IgG in water. It is greater than 99% IgG, 95% of which is monomeric. Anticomplement activity is removed by reduction and alkylation of disulfide bridges. Concentrated IVIG preparations are pooled from 10,000 to 15,000 donors and contain a vast assortment of idiotypes. It is estimated that one gram of IVIG contains approximately 4 × 1018 molecules, capable of recognizing more than 10 million antigenic determinants.54 Nearly all commercial forms of IVIG have been demonstrated to have high titers of antibodies capable of neutralizing activity against PTSAgs22 and hemolysins (P.M. Schlievert, PhD, written communication, April 10, 2000).

IVIG Intraocular Distribution

The blood-retinal barrier has been held responsible for poor penetration of most drugs and high-molecular-weight substances into the posterior segment of the eye, either from the blood or from the periocular tissues. The blood-retinal barrier exists at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium and the retinal capillary endothelial cells. However, recent reports have suggested that high-molecular-weight compounds such as dextrans (150 kd) and IgG (approximately 150 kd) can diffuse across the sclera into both the choroid and the retina.63–65 In the reverse direction, molecules as large as 38.9 kd have been shown to diffuse across the internal limiting membrane of the retina.66 However, studies on the distribution and fate of intravitreally placed IgG molecules are scarce.67 Because intraocular penetration of intravenously administered immunoglobulins is likely to be quite limited based on the above considerations, intravitreal administration of IG would likely be necessary to attenuate toxin-mediated damage in endophthalmitis.

Present Study

Hypothesis

The hypothesis of this study is that intravitreally injected human IG attenuates the inflammatory and tissue destructive effects of virulence factors elaborated by S aureus. The hypothesis is tested in an experimental rabbit model of noninfectious S aureus toxin-mediated endophthalmitis. A requisite to the testing of this hypothesis is a demonstration that intravitreally injected human IG is of itself relatively noninflammatory and that it persists in the eye of sufficient duration to have a therapeutic effect.

Aims

The aims of the study are twofold: (1) to assess the intraocular distribution, persistence, and histologic effects of intravitreally injected human IG, and (2) to establish proof of principle for a neutralizing effect on the clinical and histologic manifestations of toxin-induced endophthalmitis by polyspecific, pooled human IG. The evaluations that follow are described in two parts, I and II.

I. INTRAVITREAL INJECTION OF HUMAN IMMUNE GLOBULIN: INTRAOCULAR DISTRIBUTION AND RETINAL RESPONSE BY IMMUNOHISTOCHEMICAL EVALUATION IN THE RABBIT EYE

General Approach

In this study, characterization of the ocular response to intravitreally injected IG in the normal rabbit eye was performed by histologic evaluation. Immunohistochemistry was used to identify the intraocular distribution and persistence of IG. These evaluations were performed at intervals up to 5 days after injection, a time period during which visual outcome in acute endophthalmitis in humans is strongly determined.31 Protein expression by Müller cells was used as an indicator of a pathologic retinal state. Under physiological conditions, Müller cells in the human and rabbit retina contain intermediate filaments such as vimentin but not glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), whereas in pathological conditions such as retinal injury and retinal degeneration, they have been shown to contain both GFAP and vimentin.68,69 The expression of vimentin and GFAP by Müller cells was used to assess the response of nonneural retinal cells to intravitreal IG injection. Western blotting was used to demonstrate whether intact IgG molecules persisted within the vitreous.

Methods

Intraocular Injections and Tissue Processing

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval from the Medical College of Wisconsin was obtained prior to initiating all animal experiments. New Zealand White rabbits, 2 to 3 kg, were housed and handled in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Visual Research. Prior to intravitreal injection, animals were anesthetized with intramuscular ketamine (20 mg/kg) and xylazine (1 mg/kg), and topical proparacaine hydrochloride. The entire procedure was performed with full aseptic precautions and under adequate visualization. Pupils were dilated with phenylephrine 2.5% and tropicamide 1% eye drops.

A total of 24 rabbit eyes received intravitreal injections of varied doses (0.5 mg, 2.5 mg, 10 mg, 20 mg, 30 mg in volumes of 100 μL to 300 μL, depending on dose) of commercially available IG (Gamimune N, 10%, Bayer Corporation, Elkhart, Indiana) or with diluent (balanced salt solution, BSS; Alcon, Fort Worth, Texas). The eyes were harvested on postinjection days (PIDs) 1, 2, 3, and 5. Of these, two eyes each were harvested on days 1, 2, and 3 in the 10-mg and 20-mg groups. The remaining 12 eyes were harvested on day 5, with two eyes each in the five dosage groups and two eyes with BSS injection. Prior to each intravitreal injection, 100 to 300 μL of aqueous humor was aspirated from the anterior chamber to reduce the risk of elevated intraocular pressure. Additionally, two normal rabbit eyes (no injections) were included in this study as negative controls. For all animals, only one eye was used. No intravitreal hemorrhage was observed with indirect ophthalmoscopy following injection. Animals were euthanized with intracardiac injections of pentobarbital (25 mg/kg) at the above stated intervals. Immediately after enucleation, 0.5 to 1 mL of vitreous fluid was aspirated from nine eyes with IG injection and seven control eyes and stored at –20°C. Immediately following enucleation, the eyes were fixed in 10% formalin.

Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

Enucleated globes were processed and the central papillary optic disk portion of the globe was embedded in paraffin. Five-micron paraffin sections were mounted on poly-l-lysine coated slides. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for light microscopy. All eyes were evaluated for histologic changes including inflammatory cell response.

After deparaffinization and hydration, endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by a 5-minute incubation in 3% hydrogen peroxide (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, Missouri). The sections were then incubated with a serum-free protein blocking solution (DAKO, Carpinteria, California). Biotinylated rabbit antihuman IgG, monoclonal mouse antiglial fibrillary acidic protein, and monoclonal mouse antivimentin (all from DAKO) were used as the primary antibodies. For the monoclonal antibodies, biotinylated antimouse IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, California) was used as the secondary antibody. The immunolabeled sites were visualized using an avidin-biotin-peroxidase kit (Vector Laboratories) with diaminobenzidine tablets (Sigma) used at the development stage. All sections were allowed to develop for 10 minutes, then immediately washed and counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Sigma). Controls included normal rabbit eyes, rabbit eyes injected with diluent only (BSS), and human tonsil tissue (as positive control). Negative controls included omission of the primary antibody.

Western Blot of Vitreous

Vitreous was removed by aspiration immediately after enucleation, collected in Eppendorf tubes, and frozen at –20°C until analysis. Vitreous samples were mixed with an equal volume of 2X Laemmli’s SDS electrophoresis buffer,70 boiled, and loaded on gels in triplicate, using three different volumes, followed by electrophoresis in 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Biorad Criterion precast gel). IG samples were electrophoresed in parallel as a positive control. Western blots were prepared by standard methods and probed with a 1:50,000 dilution of peroxidase-conjugated antihuman IgG antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc, West Grove, Pennsylvania). Bands were visualized with the Enhanced Chemiluminescence (EML) detection system (Amersham, Piscataway, New Jersey).

Results

Histopathology

Ten of the 24 eyes showed minimal mononuclear cell infiltration. These cells were predominantly located in the prepapillary (Figure 1) or preretinal area and were first noted on the second day. This cellular response was independent of the IG dose. None of the eyes showed intraretinal inflammatory cells. One eye showed red blood cells in the vitreous.

Figure 1.

Light micrograph showing the optic nerve head region: mononuclear cells are seen in the prepapillary vitreous following intravitreal injection of human immune globulin (hemtoxylineosin, ×125).

Immunohistochemistry and Western Blot

Intense IG labeling was localized to the vitreous in all eyes and was seen at all time points studied (days 1, 2, 3, and 5), irrespective of the amount of IG injected. There was no appreciable subjective decrease in intensity of staining from day 1 to day 5. In the anterior uvea, the posterior layer of the iris epithelium and the inner layer of the ciliary epithelium (Figure 2) showed intense staining. On day 1, IG was distributed throughout the retina extending from the internal limiting membrane to the outer border of the photoreceptor layer. Staining was more intense in the inner nuclear layer (both diffuse extracellular and intracellular) (Figure 3) and in the outer extent of the outer segments layer. In some sections, the intracellular labeling in the inner nuclear layer showed a dendritic pattern; however, it did not show a distinct transretinal vertical configuration, characteristic of the distribution of the Müller cell processes. The staining pattern in the retina persisted into day 5. The retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) also showed positive staining for IG, but no staining could be detected in the sub-RPE space or in the choroid (Figure 4). The RPE staining was noted at all time points and was independent of the dosage used. Intense staining was also noted in the axonal bundles of the optic nerve head around the major vascular channels (Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph showing immunolocalization of immunoglobulin molecules following intravitreal injection: intense staining is localized to the inner epithelial layer of the ciliary processes (×125).

Figure 3.

Distinct immunoglobulin-specific intracellular staining is seen in the inner nuclear layer of the retina following intravitreal injection of human immune globulin. All the other layers of the neurosensory retina show diffuse staining (×250).

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph of the peripapillary retina in the rabbit eye showing diffuse immunoglobulin-specific staining in all the retinal layers. Staining is more intense in the vitreous and in the outer extent of the outer segment layer. The choroid does not show any staining (×250).

Figure 5.

Immunoglobulin-specific staining seen in the prepapillary vitreous and around major blood vessels in the optic nerve head, following intravitreal injection of human immune globulin (×125).

Vimentin immunolabeling was observed in the retina as radially oriented processes extending from the internal limiting membrane to the outer limiting membrane, representing Müller cell morphology. This staining was seen in both IG-injected, control (BSS), and normal eyes. However, the Müller cells did not express GFAP in all the eyes studied (including control eyes). GFAP staining was noted only in the optic nerve head and in the innermost retina adjacent to the optic nerve head. The immuno-staining results were confirmed by Western blotting of the vitreous, which showed full-length IgG in the vitreous throughout the 5-day time course of the study (not shown).

Discussion

Systemically administered IG penetrates poorly into the retina in patients with an intact blood-retinal barrier.71 Under physiological conditions, the blood-retinal barrier includes the retinal vascular endothelium, the retinal pigment epithelium, and the tight junctions at the base of the inner layer of the ciliary epithelium. Like the blood-brain barrier, these effectively block the penetration of plasma proteins, including immunoglobulins, from the blood into the retina. Raising the serum IG concentration has not been associated with significant increase in cerebrospinal fluid concentration72 and is therefore unlikely to work for intraocular application. Direct intravitreal injection of IG would circumvent the blood-retinal barrier, but there are no data on the fate of IG molecules in the vitreous. The results of this study provide new information on the fate of IG molecules following intravitreal injection, including host inflammatory response, and on the response of Müller cells to the injection.

In this study the distribution of intravitreally injected IG was identified by immunohistochemical localization of IG molecules in the rabbit eye at various intervals after injection. The results indicate that IG rapidly diffuses throughout the neural retina by day 1 and can be detected for the duration of the study (5 days). The IG molecules are distributed diffusely through the extracellular space and are also internalized by cell types in the inner nuclear layer, RPE cells, and the inner layer of the ciliary epithelium. The 150-kd IgG molecules are able to cross the intact internal limiting membrane, which therefore does not constitute an efficient barrier to the IgG molecules injected into the vitreous. This is consistent with previously published data on diffusion of IgG molecules across the internal limiting membrane in the peripapillary area.67

Although the immunohistochemical technique used in this study detects an IgG epitope (and not the whole molecule), it is reasonable to conclude that IgG molecules have not undergone any cleavage over the time period studied. Western blot analysis of the vitreous at PID 5 shows intact IgG molecules. Similarly, the intraretinal IG is also likely to be intact, given that pharmacokinetic studies of IG preparations following intravenous administration in healthy subjects show a half-life of 14 to 24 days.73 Of note is that the in vivo half-life of Gamimune N (used in this study) as reported by the manufacturer exceeds or equals the 3-week half-life reported for IgG in the literature. It is also known that when the blood-retinal barrier is circumvented, IgG molecules placed in the periocular space do diffuse across the sclera into both the choroid and the retina in significant amounts and into the vitreous and aqueous in negligible amounts.63,64 The reasons for the rapid and significant intraretinal diffusion noted in this study are twofold: the IG molecules were placed directly in the vitreous, and relatively large molar quantities of IG were injected.

The host response following intravitreal IG injection was also studied by evaluating inflammatory cell infiltrate and expression of GFAP by Müller cells. Müller cells in rabbits and humans express vimentin constitutively, but they express GFAP only in response to retinal injury or degeneration.68,69 GFAP was therefore used as a marker to assess the response of the nonneural retinal elements to intravitreal injection of IG. Only 10 of the 24 eyes showed minimal mononuclear cell infiltration in the prepapillary vitreous, and none in the retina itself. Also, even at PID 5, and with up to 30 mg of IG injection, Müller cells expressed only vimentin and not GFAP. Minor trauma such as that caused by a scleral puncture (similar to the technique used for the intravitreal injection used here) does not lead to GFAP upregulation by Müller cells.69 GFAP immunoreactivity in rabbit retina has been reported to vary with the type of fixation technique used.74 In this study, fixation artifact did not explain absence of GFAP expression by Müller cells, since GFAP immunoreactivity was noted in nonneural, non-Müller elements in the papillary region. Therefore, absence of retinal response by nonneuronal cells to intravitreal injection of IG most likely represented the absence of GFAP up-regulation in Müller cells.

This study shows that intravitreal injection of IG is well tolerated and intact IG persists in the vitreous and retina for at least 5 days postinjection. Also, IG molecules at the dose range employed in this study diffuse rapidly into all layers of the neural retina. The ocular tolerance, tissue penetration, and persistence of intravitreal IG are desirable characteristics that might allow attenuation of toxin-mediated damage in acute endophthalmitis.

II. INTRAVITREAL INJECTION OF HUMAN IMMUNE GLOBULIN: ATTENUATION OF THE EFFECTS OF STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS CULTURE SUPERNATANT IN A RABBIT MODEL OF TOXIN-MEDIATED ENDOPHTHALMITIS

General Approach

Evaluations were performed to establish proof of principle for a neutralizing effect of IG on the manifestations of toxin-induced endophthalmitis. In this study, immunoreactivity of IVIG against known, toxic, components of S aureus supernatant (pooled toxin, PT) was demonstrated by Western blotting. In a rabbit model of toxin-mediated endophthalmitis induced by intravitreal PT, clinical and histopathologic measures were used to determine whether IG neutralized the effects of PT.

Methods

Pooled Bacterial Toxin Preparation

S aureus RN4220 is a derivative of strain 8325-4 modified for genetic manipulation which primarily produces beta hemolysin (molecular weight [MW]: approximately 35 kilodaltons [kd]).75 Strain RN4220 was chosen because of extensive laboratory experience with this line and the relative ease with which some aspects of toxin production can be manipulated. The particular RN4220 used in this study also produces toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1; MW: approximately 22 kd), alpha hemolysin (MW: approximately 32 kd), and delta hemolysin (MW: approximately 3 kd) in small amounts (P.M. Schlievert, PhD, oral communication, October 2000). The technique for collecting culture supernatant has been previously described.76 Bacteria were propagated overnight with aeration at 37°C in 1,200 mL of beef heart extract medium (BHM).77 Briefly, this medium is prepared from a tryptic digest of beef hearts that is dialyzed across 4,000 to 6,000 MW cutoff dialysis tubing. The insoluble residue is discarded, and the dialysate is sterilized, supplemented with glucose buffer, and inoculated with RN4220. After bacterial growth, extracellular proteins were precipitated from 100 mL of culture medium with four volumes of ethanol chilled overnight at 4°C. The precipitate was resuspended in 10 mL of double distilled water. The suspension was then centrifuged at 10,000g for 20 minutes to remove cellular debris. The supernatant was removed and dialyzed (12,000 to 14,000 MW cutoff) against 2 L of water overnight at 4°C.25 This concentrated culture supernatant (pooled toxin, PT) contained approximately 60 mg protein/mL. Bacteria-free BHM was similarly precipitated to produce a toxin-free control solution. Sterility was maintained during the entire procedure.

Purified Bacterial Toxin Preparation

Beta hemolysin was purified from RN4220 culture supernatant following the initial steps outlined above. Once the culture supernatant was collected, beta hemolysin was separated using an isoelectric focusing technique.75 TSST-1 was derived from an RN4220 line containing the vector pCE107. Following collection of culture fluids, TSST-1 was separated with isoelectric focusing using successive gradients of pH 3.5 to 10 and pH 6 to 8.78

Western Blotting: Evaluation of Reactivity of IG Against Known S aureus Toxins

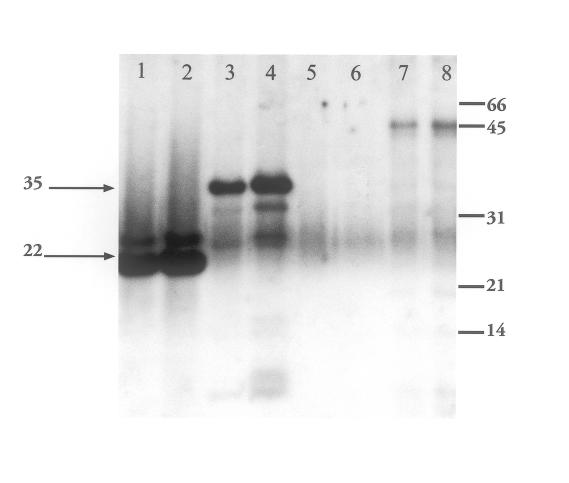

Western blotting was performed to determine whether IG (Gamimune N, 10%) binds to known toxins produced by S aureus (beta hemolysin and TSST-1; source: laboratory of Patrick M. Schlievert, PhD, Minneapolis, Minnesota) and to proteins, including toxins, in PT. Known toxins, PT, and control BHM were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under reducing conditions (5 mM β-mercaptoethanol) using 12.5% separating gels. Protein loading was empirically determined and is reported with the “Results.” Separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and blotted overnight with a 1:10,000 dilution of IG. Bands were visualized with the Enhanced Chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, New Jersey) after exposure to a donkey antihuman secondary antibody (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Western blot of Staphylococcus aureus culture supernatant (pooled toxin) and purified exotoxins. Nitrocellulose membranes probed and then visualized with ECL detection system. Primary antibody: 1:10,000 dilution of 10% Gamimune; secondary antibody: donkey antihuman. Lanes 1 and 2: toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1) 0.2 and 0.5 μg; lanes 3 and 4: beta hemolysin (BHL) 0.2 and 1.25 μg; lanes 5 and 6: beef heart media; lanes 7 and 8: concentrated culture supernatant 0.5 and 1.0 μg. Molecular weight markers (Bio-Rad) indicated on the right (in kilodaltons) are serum albumin (66), ovalbumin (45), carbonic anhydrase (31), trypsin inhibitor (21), and lysozyme (14). The upper arrow indicates BHL. The lower arrow indicates TSST-1.

Intraocular Injections of Pooled Toxin and Clinical Examination

Preliminary studies indicated that an intravitreal injection of PT containing 330 μg protein reproducibly created intraocular inflammation with a red reflex but no ophthalmoscopically detectable fundus details. This pathologic outcome was chosen because it closely mirrors the degree of inflammation reported in a rabbit model of S aureus endophthalmitis involving live bacteria.12 It was also desirable to create a model of intraocular inflammation similar to that typically seen in a clinical case of S aureus endophthalmitis with presenting visual acuity of count fingers to hand motions.

Thirty-six rabbits were divided into three groups, each with six experimental and six control animals, in which the timing of the intravitreal injections was varied. In group 1 (simultaneous), PT and IG were mixed and delivered simultaneously; in group 2 (sequential), IG was injected immediately after PT; and in group 3 (delayed), IG was injected 6 hours after PT. Group 1 data consisted of two sets each of three experimental and three control rabbits that were sacrificed on either PID 7 or 9. All rabbits in groups 2 and 3 were sacrificed on PID 9.

The volume of IG used in this study was determined by two competing factors regarding the nonvitrectomized eye. Though it was desirable to inject the largest possible volume of IG to maximize IG and toxin interaction, injection volumes were limited to less than 250 μL by associated intraocular pressure elevation. Although removal of up to 300 μL of aqueous was possible, it was determined that 200 μL of aqueous could be safely aspirated from the anterior chamber without risk of lens or iris damage. Therefore, an IG volume of 145 μL was chosen for this portion of the study, and other parameters were adjusted accordingly.

Prior to intravitreal injection, 150 μL (group 1) or 200 μL (groups 2 and 3) of aqueous humor was aspirated with a tuberculin syringe to reduce intraocular pressure and reduce the risk of vascular occlusion. For group 1, 5 μL of the concentrated PT (containing 330 μg protein) was mixed with 145 μL IG (14.5 μg) and injected within 10 minutes through the pars plana into the midvitreous using a 30-gauge needle and a tuberculin syringe. For the other groups, 5 μL of the concentrated PT was diluted to 50 μL with BSS and injected into the midvitreous. (Increasing the 5 μL volume to 50 μL allowed for reliable toxin delivery into the midvitreous cavity using a tuberculin syringe.) IG (145 μL) was then injected at a site 90 degrees away, either immediately (group 2) or 6 hours after (group 3) PT injection. Control animals in all groups received 145 μL BSS in lieu of IG. Materials were prepared and injected under sterile conditions. For all animals, one eye only was used. Immediately following injection, all eyes were examined for intraocular complications.

For all animal groups, slit-lamp biomicroscopy and indirect ophthalmoscopy were performed four times over 9 days postinjection by one investigator and two masked vitreoretinal surgeons experienced with the management of clinical endophthalmitis. In group 1 and group 2, examinations were performed on PIDs 1, 3, 5, and 8. Group 3 examinations were performed on PIDs 2, 4, 6, and 9. At each time point, examination of six experimental and six control eyes was performed except for PID 8 in group 1 when there were only three experimental and three control eyes.

The anterior chamber reaction and fundus reflex were graded for evidence of ocular inflammation using an adaptation of a 0 to 4 grading scale reported by others (Table 1).10 The mean score for each parameter was determined for the six eyes in each group, and control and experimental groups were analyzed for statistically significant differences (P < .05) using the Mann-Whitney test at each time point except for the final day in group 1 when there were only three eyes in each of the experimental and control groups.

Table 1.

Clinical grading scheme for severity of ocular inflammation10

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| Anterior Chamber | |

| 0 | Normal |

| 1 | 5–10 cells/field |

| 2 | 10–20 cells/field |

| 3 | 20–50 cells/field |

| 4 | >50 cells/field |

| Fundus Reflux | |

| 0 | Normal |

| 1 | Slightly diminished |

| 2 | Diminished |

| 3 | Moderately diminished |

| 4 | White |

Histopathology

Animals were killed by an intracardiac injection of pentobarbital (25 mg/kg) on PID 7 or 9, and the treated eyes were enucleated and fixed in 10% formalin for histopathologic analysis. Eyes were embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin by standard protocols. Sections were examined and scored by an investigator masked to the identity of the treatment group. Each eye received scores for four tissues using grading scales for severity changes adapted from the work of others.10,34 The cornea, anterior chamber, and vitreous each received a single score of 0 to 3 (Table 2). For the retina, a template was used to divide each retinal section into six regions, each of which was graded separately using a 0 to 4 scale (Table 2). A single retinal score per eye was obtained by taking the mean of the six regional scores, and the Mann-Whitney test was used to determine statistically significant differences (P < .05) between experimental and control groups.

Table 2.

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| Cornea | |

| 0 | Normal |

| 1 | Partial-thickness infiltration of inflammatory cells |

| 2 | Segmental full-thickness infiltration of inflammatory cells |

| 3 | Total full-thickness infiltration of inflammatory cells |

| Anterior Chamber | |

| 0 | Normal |

| 1 | Partially filled with fibrin |

| 2 | Partially filled with fibrin and infiltrate |

| 3 | Completely filled with infiltrate |

| Vitreous | |

| 0 | No inflammation |

| 1 | Inflammatory cells without focal abscess |

| 2 | Partially filled with abscesses and infiltrate |

| 3 | Completely filled with infiltrate |

| Retina | |

| 0 | Normal |

| 1 | Mild alteration of retinal architecture |

| 2 | Outer nuclear layer buckling, mild inner layer disruption, and separation from outer nuclear layer |

| 3 | Full-thickness retinal disruption. Photoreceptor layer folds, with retinal detachment. Inner and outer nuclear layers disrupted but still distinguishable; outer nuclear layer contiguous. |

| 4 | Full-thickness retinal disruption, with disorganization of all retinal layers, outer nuclear layer disorganized or necrotic, inner layers missing. |

Results

Reactivity of IG With S aureus Products

When IG was used as a primary antibody for Western blot analysis, we observed reactivity with numerous proteins in the PT, including a prominent unidentified high-molecular-weight protein (Figure 1). The absence of comigrating bands in the control BHM suggests that the IG immunoreactive proteins in the PT are bacterial products. To determine whether the IG can react with any known S aureus toxins, which may constitute a small fraction of the protein in the total PT and therefore contribute little to the blotting signal, beta hemolysin and TSST-1 were purified from bacterial supernatants and also blotted with IG. As shown (Figure 1), IG shows reactivity with both beta hemolysin and TSST-1.

Clinical Examination

Pooled Toxin Alone

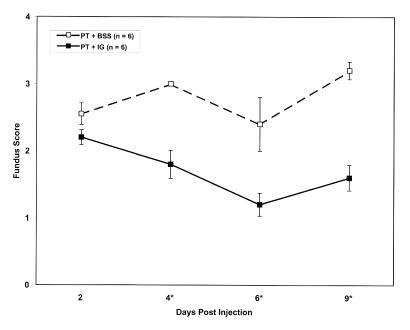

Intravitreal delivery of PT alone produced a grade 3 to 4 anterior chamber reaction on PID 1. This reaction declined until it resolved by days 5 to 7. The fundus reflex was diminished in all eyes by PID 1. Despite the obscuration of most retinal details in all eyes on PID 1, intraretinal hemorrhages could be observed in some. Over the first 5 days postinjection the fundus reflex worsened in most eyes and remained diminished at approximately the same level on PIDs 5 through 9. The initial decline in the reflex was attributed to vitreal inflammation. To a variable extent, a white membrane would form on the posterior surface of the lens by PID 2, would continue to proliferate on PIDs 2 to 4, and then would stabilize. This membrane would continue to mature even though anterior segment inflammation was resolving, and it prevented adequate evaluation of the posterior segment. The fundus reflex appearance on PID 7 is illustrated in Figure 7 (top), and scores for the fundus reflex over the 8- to 9-day time course are shown in Figure 8 (broken lines).

Figure 7.

Fundus reflex of rabbit eyes 7 days after pooled toxin (PT) injection, without or with Gamimune (IG). Top, PT alone. Bottom, PT, simultaneous IG.

Figure 8.

Time course of fundus scores following injection of pooled toxin (PT), without or with Gamimune (IG). Top, PT and simultaneous injection of balanced salt solution (BSS) or IG. Middle, PT and sequential injection of BSS or IG. Bottom, PT and delayed injection of BSS or IG. Y-axis represents mean fundus score ± standard error. PT and BSS: broken line; PT and IG: solid line. **n = 6 eyes per data point except for postin-jection day 8 in the simultaneous injection group (top) where n = 3 eyes per data point. *Significant difference exists with P value less than .05 calculated from Mann-Whitney test

Pooled Toxin and Simultaneous Injection of IG

When PT was mixed with IG prior to injection, an anterior chamber reaction was seen in only three of six eyes and was limited to grade 1. The fundus reflex (Figure 7, bottom) was essentially normal throughout the time course, and retinal details were easily seen. Fundus reflex scores over the time course are graphed in Figure 8 (top). Compared to eyes receiving PT and BSS, the average fundus reflex scores from eyes receiving IG were significantly lower at all time points (Figure 8, top).

Pooled Toxin and Sequential Injection of IG

When IG was injected immediately following PT, the expected inflammatory response was attenuated compared to eyes receiving PT alone (Figure 8, middle). The difference in the fundus reflex scores between the two groups became greater over the 9-day course and could be attributed to a worsening of the fundus reflex in the eyes not receiving IG. The differences were statistically significant at all but the second time point. Compared with eyes receiving simultaneous injections of PT and IG, the fundus scores of eyes receiving sequential injections were higher (ie, more diminished), particularly at earlier time points (Figure 8, top and middle).

Pooled Toxin and Delayed Injection of IG

When injection of IG was delayed by 6 hours, only a slight attenuation of the expected inflammatory response was observed. The fundus reflex was diminished more than in eyes receiving simultaneous or sequential injections of IG (Figure 8). Despite the diminished reflex, fundus scores were significantly lower at all but the first time point when compared with eyes not receiving IG (Figure 8, bottom). Retinal details were obscured throughout the time course.

Histopathology

Pooled Toxin Alone

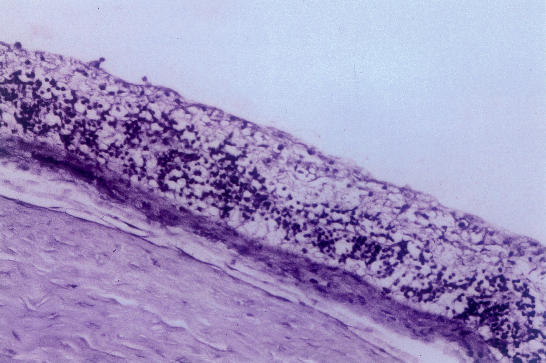

Essentially no inflammatory response was found in the cornea and anterior chamber of these eyes (Figure 9). The vitreous cavity was partially filled with inflammatory cells. Some eyes had abscesses and others did not. Full-thickness retinal disruption was evident with ganglion cell loss, increased vacuolization of inner nuclear layers, complete loss of photoreceptors, and choroidal thickening observed in most sections (Figure 10, top). Interspersed areas of focal retinal thinning due to loss of cellular elements were observed.

Figure 9.

Histologic score following injection of pooled toxin (PT), without or with Gamimune (IG). Top, PT and simultaneous injection of balanced salt solution (BSS) or IG. Middle, PT and sequential injection of BSS or IG. Bottom, PT and delayed injection of BSS or IG. Y-axis represents mean fundus score ± standard error. PT and BSS: gray bars; PT and IG: black bars. n = 6 eyes per data point. ** All eyes were collected on postinjection day 9 except for 6 eyes (3: PT and BSS; 3: PT and IG) in the simultaneous injection group (top) collected on postinjection day 7. *Significant difference exists with P value less than .05 calculated from Mann-Whitney test.

Figure 10.

Histopathology of rabbit eyes 9 days after pooled toxin (PT) injection, without or with Gamimune (IG). Top, PT alone (hematoxylineosin, ×125). Bottom, PT, simultaneous IG (hematoxylineosin, ×82.5).

Pooled Toxin and Simultaneous Injection of IG

In these eyes, a mild inflammatory response in the vitreous cavity was observed. Compared to eyes receiving PT alone, there was a marked preservation of retinal architecture with the presence of distinct layers composed of intact cells (Figure 10, bottom). In some sections, vacuolization of the inner nuclear layers and choroidal thickening were observed.

Pooled Toxin and Sequential Injection of IG

When IG was injected immediately following PT, an attenuation of the expected histologic response in the retina but not in the vitreous was observed (Figure 9, middle). Compared to eyes receiving PT simultaneously with IG, the retinal architecture was slightly more disrupted but still significantly less than in eyes not receiving IG. Focal areas of inner nuclear layer vacuolization, disruption of the ganglion cell layer, retinal edema, photoreceptor loss, and choroidal thickening were noted. In other sections, preserved retinal architecture was observed.

Pooled Toxin and Delayed Injection of IG

When IG was injected 6 hours after PT, the histologic appearance of all tissues was indistinguishable from eyes receiving PT alone (Figure 9, bottom). There was full-thickness retinal disorganization in most sections with ganglion cell loss, increased vacuolization of inner nuclear layers, complete loss of photoreceptors, and choroidal thickening. As in eyes receiving PT alone, some sections contained focal areas of retinal thinning due to cell loss.

Discussion

The rabbit model has been extensively used in the study of endophthalmitis. The rabbit eye may differ from the human eye in its response to intravitreally injected bacteria. For instance, the rabbit eye almost always self-sterilizes after intravitreal injection of live S epidermidis organisms, a phenomenon not observed to the same degree in the human eye.79 Nevertheless, the severity of infection in experimental endophthalmitis in the rabbit eye seems to mirror that observed clinically in the human eye across bacterial species varying in their degrees of virulence and ability to elaborate toxins.2,10,16,20,34,79 To the extent that bacterial toxins are responsible for a similarity in host response, it seems reasonable to suggest that the inflammation and retinal damage observed in the rabbit eye from injected S aureus culture supernatant (or its exotoxins) would also likely occur in the human eye, although not necessarily at the same dosage or concentration. Such damage would likely be of clinical significance.

Using Western blotting techniques, it was determined that IG could bind purified toxins as well as numerous proteins from S aureus RN4220 culture supernatant. These findings suggest that specific antibodies are present in commercially available pooled immunoglobulin that are capable of binding bacterial products, thus providing a biochemical basis for the attenuated clinical and histologic effect observed when IG and PT interact. Though S aureus RN4220 is a modified laboratory strain that may prove to be more or less virulent than other S aureus strains, it has been well studied and can be manipulated to produce different toxins, thus providing a framework for further study involving antitoxin therapy.

Quantitative pharmacokinetics of IG remain largely unknown, but most certainly influence the therapeutic effects of IG in this model. When IG was injected immediately following PT, the toxic effects of PT were definitely attenuated clinically and histologically, but less so when compared with eyes receiving PT simultaneously injected with IG. This observation would suggest that optimizing the mixing of IG with bacterial virulence factors elaborated in vivo might facilitate a therapeutic effect. The influence of vitreous humor on the interaction between IG and PT remains unexplored.

The rapidity with which IG is capable of inactivating the biological activity of PT would suggest that a mode of administration that promotes interaction between IG and bacterial toxin could ameliorate the destructive effects of the toxins if given at an opportune time. In S aureus infection, significant toxin production typically does not occur until the postexponential growth phase,15 providing a potential window of opportunity for therapeutic intervention. In a rabbit model of endophthalmitis produced by the intravitreal injection of S aureus, bacteria grew exponentially during the first 24 hours.12 Intraocular inflammation was observed at 24 to 48 hours postinjection, whereas attenuation of the electroretinography recording did not begin to occur until 48 hours postinjection.12 Thus, treatment that occurs within this time frame, or perhaps not much later than this, might favorably influence the course of endophthalmitis. The importance of timely intervention prior to bacterial release of large quantities of exotoxins is also suggested by our study. Little difference was noted clinically, and none histologically, when IG injection was delayed 6 hours following PT injection, most likely indicative of the rapidity of tissue destruction from abrupt exposure to a suprathreshold dose of toxin. Reduced effect with delayed treatment might relate to the marked fulminance of this noninfectious model and differ from human endophthalmitis. Because clinical endophthalmitis is most likely associated with a gradually increasing concentration of a variety of toxins, rather than a bolus dose, the concept of toxin neutralization being of potential benefit early in the course of endophthalmitis appears valid. In streptococcal and staphylococcal toxic shock syndromes, intervention with IVIG appears helpful even after onset of disease manifestations,22,23 suggesting that therapeutic opportunity might also exist in endophthalmitis cases already clinically manifest.

The commercial availability of pooled, polyspecific IG (IVIG) is a distinct advantage for its potential therapeutic application in the human eye. The risk-benefit ratio for such therapy would require that the risks of local toxicity, immune response, and systemic side effects be considered. Risks include that of transmission of blood-borne pathogens, because the product is a biological product derived from plasma pooled from human donors. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis B and C are agents of greatest concern, with cases of hepatitis B and C transmission being reported with systemic administration.80–82 However, preparations after May 1994 are considered to have a high degree of safety with respect to viral contamination due to screening of donors and adoption of procedures that inactivate viruses, with no cases of hepatitis C virus transmission having occurred since about that time. In addition, there has been no transmission of HIV by any preparation of IVIG, though reverse transcriptase of possible viral origin was found in the serum of two recipients in 1986. These issues have been discussed at length by Grob83 and Yap.82 It might be speculated that the above risks of IVIG-associated disease transmission might be reduced, though not absolutely eliminated, because of the smaller dosages likely to be used intravitreally and the relatively poor access to the systemic circulation offered by such a route.

Serious side effects ascribed to systemic administration of IVIG include headache and aseptic meningitis (1% to 11%), vasomotor reactions, thromboembolic events, and acute renal failure. Most have occurred after multiple intravenous infusions, mostly with dosages of approximately 0.35 to 1 gm/kg per day, huge amounts in comparison to a dosage that might be proposed for the eye (milligrams to decigrams). Limited experience with IVIG injected intraventricularly and intrathecally for treatment of viral CNS infections has shown no associated serious toxicity,84–88 suggesting that intraocular injection of IVIG might similarly be associated with low morbidity.

Because of the polyspecific nature of standard preparations of IVIG,89 relatively large intravenous doses are required to achieve systemic effect. In addition, variability in reactivity between lots of commercially available IVIG has been observed, with some containing low levels of bacterial antibodies.90 Correlation between titers of bacterial antibodies and those against their elaborated toxins has not been evaluated to the author’s knowledge. To increase potency, hyperimmune globulins (HYPERIVIG) have been formulated, which contain high titers of specific antibodies from plasma of donors immunized with appropriate vaccines or from donors screened for naturally occurring high antibody titers. Systemic administration has been associated with promising results.91 Such preparations have been made for relatively few bacterial species targets, however. Significant clinical need is proposed for HYPER-IVIG for treatment of systemic staphylococcal, streptococcal, and gram-negative infections.89 If developed, HYPER-IVIG might have potential applications to endophthalmitis in the human eye, particularly if it contains a corresponding increase in antibody titers against elaborated toxins. The availability of recently developed rapid tests for various bacterial infections, if proven applicable to clinical endophthalmitis, would facilitate use of such targeted therapy.

SUMMARY

This is the first study of which the author is aware that evaluates the effect of polyspecific immunoglobulin therapy against bacterial exotoxins in endophthalmitis. The ocular tolerance, tissue penetration, and persistence of intravitreally injected IG observed in this study appear compatible with its proposed application as antitoxin therapy in acute endophthalmitis. Further investigation is required evaluating such factors as the interaction of ocular tissues with IG-bound toxin, efficacy of IG in infected bacterial models of endophthalmitis, the ocular immune host response, immune-complex formation, interaction of IG with antibiotics, effect of vitrectomy, and timing of intervention.

This study supports the hypothesis that intravitreally injected human immune globulin reactive to S aureus virulence factors can attenuate their inflammatory and tissue destructive effects. Pooled human IG might therefore represent a novel adjunctive therapy in the management of S aureus endophthalmitis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author wishes to acknowledge the following persons, without whose invaluable contributions this study would not have been possible: Steven L. Perkins, MD, Rajeev Buddi, MD, Janice M. Burke, PhD, William J. Wirostko, MD, Dariusz G. Tarasewicz, MD, Christine M.B. Skumatz, BS, and Patrick M. Schlievert, PhD.

Footnotes

Supported by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, New York; a National Eye Institute Core Grant (EY01931); and the Thomas M. Aaberg Retina Research Fund, Milwaukee, Wisconsin (Medical College of Wisconsin).

REFERENCES

- 1.Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study Group. . Results of the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study: a randomized trial of immediate vitrectomy and intravenous antibiotics for the treatment of postoperative bacterial endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:1479–1496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study Group. . Microbiologic factors and visual outcome in the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;122:830–846. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han DP, Wisniewski SR, Wilson LA, et al. Spectrum and susceptibilities of microbiologic factors isolates in the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;122:1–17. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71959-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kresloff MS, Castellarin AA, Zarbin M. Endophthalmitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;43:193–224. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(98)00036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waheed S, Ritterband DC, Greenfield DS, et al. New patterns of infecting organisms in late bleb-related endophthalmitis: a ten year review. Eye. 1998;12:910–915. doi: 10.1038/eye.1998.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kunimoto DY, Das T, Sharma S, et al. Microbiologic spectrum and susceptibility of isolates: part II. Posttraumatic endophthalmitis. Endophthalmitis Research Group. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128:242–244. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00113-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callegan MC, Booth MC, Jett BD, et al. Pathogenesis of gram-positive bacterial endophthalmitis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3348–3356. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3348-3356.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jett BD, Jensen HG, Nordquist RE, et al. Contribution of the pAD1-encoded cytolysin to the severity of experimental Enterococcus faecalis endophthalmitis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2445–2452. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2445-2452.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens SX, Jensen HG, Jett BD, et al. A hemolysin-encoding plasmid contributes to bacterial virulence in experimental Enterococcus faecalis endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33:1650–1656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Callegan MC, Jett BD, Hancock LE, et al. Role of hemolysin BL in the pathogenesis of extraintestinal Bacillus cereus infection assessed in an endophthalmitis model. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3357–3366. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3357-3366.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Booth MC, Atkuri RV, Nanda SK, et al. Accessory gene regulator controls Staphylococcus aureus virulence in endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:1828–1836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Booth MC, Cheung AL, Hatter KL, et al. Staphylococcal accessory regulator (sar) in conjunction with agr contributes to Staphylococcus aureus virulence in endophthalmitis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1550–1556. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1550-1556.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Supersac G, Piemont Y, Kubina M, et al. Assessment of the role of gamma-toxin in experimental endophthalmitis using a hlg-deficient mutant of Staphylococcus aureus. Microb Pathog. 1998;24:241–251. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1997.0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giese MJ, Berliner JA, Riesner A, et al. A comparison of the early inflammatory effects of an agr-/sar- versus a wild type strain of Staphylococcus aureus in a rat model of endophthalmitis. Curr Eye Res. 1999;18:177–185. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.18.3.177.5370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dinges MM, Orwin PM, Schlievert PM. Exotoxins of Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:16–34. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.1.16-34.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aguilar HE, Meredith TA, Drews C, et al. Comparative treatment of experimental Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121:310–317. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70280-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meredith TA, Aguilar HE, Drews C, et al. Intraocular dexamethasone produces a harmful effect on treatment of experimental Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1996;94:241–252. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70164-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshizumi MO, Lee GC, Equi RA, et al. Timing of dexa-methasone treatment in experimental Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis. Retina. 1998;18:130–135. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199818020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshizumi MO, Kashani A, Palmer J, et al. High dose intramuscular methylprednisolone in experimental Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 1999;15:91–96. doi: 10.1089/jop.1999.15.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jett BD, Jensen HG, Atkuri RV, et al. Evaluation of therapeutic measures for treating endophthalmitis caused by isogenic toxin-producing and toxin-nonproducing Enterococcus faecalis strains. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bohach GA, Hovde CJ, Handley JP, et al. Cross-neutralization of staphylococcal and streptococcal pyrogenic toxins by monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies. Infect Immun. 1988;56:400–404. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.2.400-404.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlievert PM. Use of intravenous immunoglobulin in the treatment of staphylococcal and streptococcal toxic shock syndromes and related illnesses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108((4 suppl)):S107–S110. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.117820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaul R, McGeer A, Norrby-Teglund A, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for streptococcal toxic shock syndrome: a comparative observational study. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:800–807. doi: 10.1086/515199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leopold IH. Management of intraocular infection. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1971;91:575–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen HF. Symposium on postoperative endophthalmitis: prevention of postoperative endophthalmitis. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1978;85:386–389. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(78)35658-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forster RK, Zachary IG, Cottingham AJ, Jr, et al. Further observations on the diagnosis, cause, and treatment of endophthalmitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1976;81:52–56. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(76)90190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peyman GA, Vastine DW, Raichand M. Symposium on postoperative endophthalmitis: experimental aspects and their clinical application. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1978;85:374–385. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(78)35659-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peyman GA, Raichand M, Bennett T. Management of endophthalmitis with pars plana vitrectomy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1980;64:472–475. doi: 10.1136/bjo.64.7.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rowsey JJ, Newsom DL, Sexton D. Endophthalmitis: current approaches. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:1055–1066. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(82)34691-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diamond JG. Intraocular management of endophthalmitis. A systematic approach. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99:96–99. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1981.03930010098011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Puliafito CA, Baker AS, Haaf J, et al. Infectious endophthalmitis: review of 36 cases. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:921–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Day DM, Smith RS, Gregg CR, et al. The problem of bacillus species infection with special emphasis on the virulence of Bacillus cereus. Ophthalmology. 1981;88:833–838. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(81)34960-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson MW, Doft BH, Kelsey SF, et al. The Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study: relationship between clinical presentation and microbiologic spectrum. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:261–272. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30326-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beecher DJ, Pulido JS, Barney NP, et al. Extracellular virulence factors in Bacillus cereus endophthalmitis: methods and implication of involvement of hemolysin BL. Infect Immun. 1995;63:632–639. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.2.632-639.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ng EW, Samiy N, Rubins JB, et al. Implication of pneumolysin as a virulence factor in Streptococcus pneumoniae endophthalmitis. Retina. 1997;17:521–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ng EW, Costa JR, Samiy N, et al. Contribution of pneumolysin and autolysin to the pathogenesis of experimental pneumococcal endopthalmitis. Retina. 2002;22:622–632. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200210000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.NEI Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study. Manual of Operations. Pittsburgh: Data Coordinating Center, University of Pittsburgh; 1990.

- 38.Kim IT, Chung KH, Koo B. Efficacy of ciprofloxacin and dexamethasone in experimental pseudomonas endophthalmitis. Korean J Ophthalmol. 1996;10:8–17. doi: 10.3341/kjo.1996.10.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu SM, Way T, Rodrigues M, et al. Effects of intravitreal corticosteroids in the treament of Bacillus cereus endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:803–806. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.6.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park SS, Samiy N, Ruoff K, et al. Effect of intravitreal dexamethasone in treatment of pneumoccocal endophthalmitis in rabbits. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:1324–1329. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100100112040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Das T, Jalali S, Gothwal VK, et al. Intravitreal dexamethasone in exogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: results of a prospective randomized study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:1050–1055. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.9.1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shah GK, Stein JD, Sharma S, et al. Visual outcomes following the use of intravitreal steroids in the treatment of postoperative endophthalmitis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:486–489. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rago JV, Schlievert P. Mechanisms of pathogenesis of staphylococcal and streptococcal superantigens. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;225:81–97. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80451-9_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bohach GA, Stauffacher CV, Ohlendorf DH, et al. The staphylococcal and streptoccocal pyrogenic toxin family. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1996;391:131–154. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-0361-9_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee PK, Schlievert PM. Molecular genetics of pyrogenic exotoxin “superantigens” of group A streptococci and Staphylococcus aureus. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1991;174:1–19. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-50998-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bohach GA, Fast DJ, Nelson RD, et al. Staphylococcal and streptococcal pyrogenic toxins involved in toxic shock syndrome and related illnesses. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1990;17:251–272. doi: 10.3109/10408419009105728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prevost G, Mourey L, Colin DA, et al. Staphyloccocal poreforming toxins. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2001;257:53–83. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56508-3_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Callegan MC, Kane ST, Cochran DC, et al. Relationship of plcR-regulated factors to Bacillus endophthalmitis virulence. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3116–3124. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3116-3124.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Callegan MC, Kane ST, Cochran DC, et al. Molecular mechanisms of Bacillus endophthalmitis pathogenesis. DNA Cell Biol. 2002;21:367–373. doi: 10.1089/10445490260099647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhakdi S, Mannhardt U, Muhly M, et al. Human hyperimmune globulin protects against the cytotoxic action of staphylococcus alpha-toxin in-vitro and in-vivo. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3214–3220. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.10.3214-3220.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cifrean E, Guidry AJ, O’Brien CN, et al. Effect of antibodies to staphylococcal alpha and beta toxins and Staphylococcus aureus on the cytotoxicity for and adherence of the organism to bovine mammary epithelial cells. Am J Vet Res. 1996;57:1308–1311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCormick JK, Tripp TJ, Olmsted SB, et al. Development of streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin C vaccine toxoids that are protective in the rabbit model of toxic shock syndrome. J Immunol. 2000;165:2306–2312. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roggiani M, Stoehr JA, Olmsted SB, et al. Toxoids of streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin A are protective in rabbit models of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5011–5017. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.9.5011-5017.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strand V. Proposed mechanisms for the efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin treatment. In: Lee ML, Strand V, eds. Intravenous Immunoglobulins in Clinical Practice. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc; 1997:23–36.

- 55.Darenberg J, Ihendyane N, Sjölin J, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin G therapy in streptoccocal toxic shock syndrome: a European randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:333–340. doi: 10.1086/376630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nydegger UE. Sepsis and polyspecific intravenous immunoglobulins. J Clin Apheresis. 1997;12:93–99. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1101(1997)12:2<93::aid-jca7>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Simone C, Delogu G, Corbetta G. Intravenous immunoglobulins in association with antibiotics: a therapeutic trial in septic intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 1988;16:23–26. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198801000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lawton JW, Robinson JP, Till G. The effect of intravenous immunoglobulin on the in-vitro function of human neutrophils. Immunopharmacology. 1989;18:97–105. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(89)90062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Skavril F, Gardi A. Differences among available immunoglobin preparations for intravenous use. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1988;7((suppl 5)):S43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Law DT, Painter RH. An examination of the structural and biological properties of three intravenous immunoglobulin preparations. Mol Immunol. 1986;23:331–338. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(86)90060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McCue JP, Hein RH, Tenold R. Three generations of immunoglobulin G preparations for clinical use. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8((suppl 4)):S374–381. doi: 10.1093/clinids/8.supplement_4.s374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schwartz RS. Overview of the biochemistry and safety of a new native intravenous gamma globulin, IGIV, pH 4. 25. Am J Med. 1987;83:46–51. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90550-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ambati J, Gragoudas ES, Miller JW, et al. Transscleral delivery of bioactive protein to the choroid and retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:1186–1191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ambati J, Canakis CS, Miller JW, et al. Diffusion of high molecular weight compounds through sclera. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:1181–1185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marmor MF, Negi A, Maurice D. Kinetics of macromolecules injected into the subretinal space. Exp Eye Res. 1985;40:687–696. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(85)90138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dias CS, Mitra A. Vitreal elimination kinetics of large molecular weight FITC-labeled dextrans in albino rabbits using a novel microsampling technique. J Pharm Sci. 2000;89:572–578. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6017(200005)89:5<572::AID-JPS2>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kristensson K, Wisniewski H. Penetration of protein tracers into the epiretinal portion of the optic nerve in the rabbit nerve. J Neurol Sci. 1976;30:411–416. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(76)90144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Okada M, Matsumura M, Ogino N, et al. Müller cells in detached human retina express glial fibrillary acidic protein and vimentin. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1991;229:380–388. doi: 10.1007/BF00927264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yoshida A, Ishiguro S, Tamai M. Expression of glial gibrillary acidic protein in rabbit Müller cells after lensectomy-vitrectomy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:3154–3160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Laemmli U. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tornquist P, Alm A, Bill A. Permeability of ocular vessels and transport across the blood-retinal-barrier. Eye. 1990;4:303–309. doi: 10.1038/eye.1990.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wurster U, Haas J. Passage of intravenous immunoglobulin and interaction with the CNS. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57((suppl)):21–25. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.suppl.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee ML, Strand V. Intravenous Immunoglobulins in Clinical Practice. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1997.

- 74.Vaughan DK, Erickson PA, Fisher S. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunoreactivity in rabbit retina: effect of fixation. Exp Eye Res. 1990;50:385–392. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(90)90139-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gaskin DK, Bohach GA, Schlievert PM, et al. Purification of Staphylococcus aureus beta-toxin: comparison of three isoelectric focusing methods. Protein Expr Purif. 1997;9:76–82. doi: 10.1006/prep.1996.0664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McCormick JK, Schlievert P. Expression, purification, and detection of novel streptococcal superantigens. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;214:33–43. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-367-4:033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schlievert PM, Shands KN, Dan BB, et al. Identification and characterization of an exotoxin from Staphylococcus aureus associated with toxic-shock syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1981;143:509–516. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.4.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schlievert PM. Immunochemical assays for toxic shock syndrome toxin-1. Methods Enzymol. 1988;165:339–344. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(88)65050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Meredith TA, Trabelsi A, Miller MJ, et al. Spontaneous sterilization in experimental Staphylococcus epidermidis endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31:181–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jarvis LM, McOmish F, Hanley JP, et al. Low transfusion rate of hepatitis G virus/GBV-C to haemophiliacs and other recipients of plasma products. Lancet. 1996;248:1352–1355. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)04041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]