Abstract

The course of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infections in squamous epithelial cells cultured in a three-dimensional organotypic raft culture was tested. In these raft cultures, normal human keratinocytes isolated from neonatal foreskins grown at the air-liquid interface stratified and differentiated, reproducing a fully differentiated epithelium. Typical cytopathic changes identical to those found in the squamous epithelium in vivo, including ballooning and reticular degeneration with the formation of multinucleate cells, were observed throughout the raft following infection with HSV and VZV at different times after lifting the cultures to the air-liquid interface. For VZV, the aspects of the lesions depended on the stage of differentiation of the organotypic cultures. The activity of reference antiviral agents, acyclovir (ACV), penciclovir (PCV), brivudin (BVDU), foscarnet (PFA), and cidofovir (CDV), was evaluated against wild-type and thymidine kinase (TK) mutants of HSV and VZV in the raft cultures. ACV, PCV, and BVDU protected the epithelium against cytopathic effect induced by wild-type viruses in a concentration-dependent manner, while treatment with CDV and PFA proved protective against the cytodestructive effects induced by both TK+ and TK− strains. The quantification of the antiviral effects in the rafts were accomplished by measuring viral titers by plaque assay for HSV and by measuring viral DNA load by real-time PCR for VZV. A correlation between the degree of protection as determined by histological examination and viral quantification could be demonstrated The three-dimensional epithelial raft culture represents a novel model for the study of antiviral agents active against HSV and VZV. Since no animal model is available for the evaluation of antiviral agents against VZV, the organotypic cultures may be considered a model to evaluate the efficacy of new anti-VZV antivirals before clinical trials.

Organotypic epithelial “raft” cultures are tissue culture systems that permit full differentiation of keratinocyte monolayers via culturing of the cells on collagen gels at the air-liquid interface. Previously, raft cultures have been successfully applied to the study of human papillomaviruses (6, 14), and more recently they have been used for the study of herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection (10, 16, 24, 25) and adeno-associated virus type 2 (15). We have also shown that the organotypic raft culture of human keratinocytes can be used as a model to evaluate both poxvirus replication and efficacy of antiviral agents (22).

Skin lesions are frequently induced by viruses and can be the first sign of a systemic disease, particularly in immunocompromised patients and children. Among the dermotropic viruses, skin lesions induced by the alphaherpesviruses herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) show characteristic histologic features.

HSV is typically responsible for mucosal lesions of the mouth and genital organs in humans. Following axonal transport, the virus reaches the dorsal root ganglia, where it establishes and maintains lifelong latent infections. Periodically, the virus reactivates, multiplies, and is transported through the axon back to a portal of entry, where it gives characteristic skin lesions (26, 27).

Primary infection with VZV results in chickenpox (varicella), a common childhood illness. As with other members of the herpesvirus family, infection with VZV is lifelong and the virus enters a latent state following the acute infection (4). Latency is associated with persistence of the viral DNA in the posterior root ganglia, and reactivation of the virus results in skin lesions characteristic of herpes zoster (shingles). Herpes zoster manifests as a localized rash in a unilateral, dermatomal distribution that is often associated with severe neuropathic pain (11, 23).

As keratinocytes are the main target cells for productive infection in vivo for both HSV and VZV, characterization of virus replication in organotypic raft cultures of these cells represents a very relevant model for studying virus-host cell interactions and antiviral agents. Here we report the infection of epithelial raft cultures with HSV and VZV, the lesions observed in these cultures being similar to those observed in human pathology. In addition, antiviral drugs were added to the organotypic raft cultures and the extent of the infection in the rafts was evaluated by histology. The antiviral effects were quantified by measuring viral titers by plaque assay for HSV and by determining viral DNA load by real-time PCR for VZV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture of primary human keratinocytes.

Primary human keratinocytes (PHKs) were isolated from neonatal foreskins. Tissue fragments were incubated with trypsin-EDTA for 1 h at 37°C. The epithelial cells were detached and cultured with mitomycin-treated 3T3 mouse fibroblasts with serum-free keratinocyte medium (Gibco, Invitrogen Corporation, United Kingdom). These PHKs were used both for antiviral assays in monolayers and for the organotypic cultures.

Viruses.

The following viral strains were used: KOS (HSV-1), a thymidine kinase-deficient (TK−) HSV-1 strain isolated from the KOS strain under pressure with acyclovir (KOS/ACVr); the reference HSV-2 strain Lyons; a wild-type HSV-2 clinical isolate (HSV-2/47); and a thymidine kinase-deficient (TK−) HSV-2 clinical isolate (HSV-2/44) recovered from the same patient (20); and the VZV reference strains Oka (TK+) and 07-1 (TK−).

Compounds.

The sources of the compounds were as follows: acyclovir [ACV, 9-(2-hydroxyethoxymethyl)guanine], GlaxoSmithKline, Stevenage, United Kingdom; penciclovir [PCV, 9-(4-hydroxy-3-hydroxymethylbut-1-yl)guanine], Novartis, Basel, Switzerland; the pyrophosphate analogue foscarnet [PFA, phosphonoformate sodium salt], Sigma Chemicals, St Louis, MO; HPMPC [cidofovir, CDV, (S)-1-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)cytosine], Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA; brivudin [(E)-5-(2-bromovinyl)-1(β-d-2′-deoxyribofuranos-1-yl-uracil, BVDU], Searle, United Kingdom; and ganciclovir [GCV, 9-(1,3-dihydroxy-2-propoxymethyl)guanine, Roche, Basel, Switzerland.

Antiviral assays.

Confluent PHKs, grown in 96-well microtiter plates, were infected at 100 CCID50 (1 CCID50 corresponds to the virus stock dilution that is infective for 50% of the cell cultures) or with 20 PFU per well for HSV and VZV strains, respectively. After 2 h of incubation at 37°C, residual virus was removed and the infected cells were further incubated with medium containing serial dilutions of the test compounds (in duplicate). After 2 to 3 (HSV) or 5 (VZV) days, the cells were fixed with ethanol and stained with Giemsa solution. Viral cytopathic effect and viral plaque formation were recorded for HSV and VZV, respectively. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) was defined as the compound concentration required to reduce viral cytopathic effect or viral plaque formation by 50%.

Organotypic epithelial raft cultures.

For the preparation of epidermal equivalents, a collagen matrix solution was made with collagen mixed on ice with 10-fold concentrated Ham's F12 medium, 10-fold reconstitution buffer, and Swiss 3T3 J2 fibroblasts. One milliliter of the collagen matrix solution was poured into 24-well microtiter plates. After gel equilibration with 1 ml of growth medium overnight at 37°C, 2.5 × 105 PHK cells were seeded on the top of the gels and maintained submerged for 24 to 48 h. The collagen rafts were raised and placed onto stainless steel grids at the interface between air and liquid culture medium. The growth medium was a mixture of Ham's F12 and Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (1:2), supplemented with 0.5 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, 10% fetal calf serum, 2mmol/liter l-glutamine, 10 mmol/liter HEPES, 1 mmol/liter sodium pyruvate, 10−10 mol/liter cholera toxin, 5 μg/ml insulin, 5 μg/ml transferrin, and 15 × 10−4 mg/ml 3,3′,5′-triiodo-l-thyronine. Epithelial cells were allowed to stratify for 10 to 12 days, the medium being replaced every other day. The cultures were then harvested, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Four sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histological examination.

Kinetic of infection of organotypic epithelial raft cultures.

After different times after lifting of the rafts on the grids, the cultures were infected with 50 μl of the different virus stocks containing approximately 500 PFU on top of the in vitro-formed epithelium, the day that the rafts were lifted being considered day 0. The medium was replaced every other day and the rafts were fixed after 12 days of differentiation and processed for histological examination.

Evaluation of antiviral compounds against HSV in organotypic epithelial raft cultures.

For the evaluation of the antiviral effects of the compounds in the raft system, two series of rafts were run in parallel, one for histological examination and the other one for quantification of viral production by plaque reduction assay. The rafts were infected with the different HSV strains 8 days after lifting and then the medium was replaced by medium containing different dilutions of the compounds. The growth medium containing different concentrations of the compounds was changed 2 days later, and after 12 days of differentiation, one series of rafts was fixed in 10% buffered formalin for histological evaluation and the other series was used to measure virus yield. Each raft was frozen in 5 ml phosphate-buffered saline and thawed to release the virus from the infected epithelium. Supernatants were clarified by centrifugation at 1,800 rpm and titrated by plaque assay in human embryonic lung (HEL) fibroblasts (ATCC CCL-137). Virus production per raft was then calculated.

Evaluation of antiviral compounds against VZV in organotypic epithelial raft cultures.

Two series of rafts were prepared to evaluate the antiviral effects of the compounds against VZV: one was processed for histology and the other one for quantification of virus DNA by real-time PCR. Rafts were infected with the different VZV strains at 4 or 5 days postlifting and the medium was replaced by medium containing serial dilutions of the compounds. The medium was changed every other day till the cultures were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for histological examination or processed for viral quantification by real-time PCR. To prepare the samples for quantitative PCR, the epithelium formed in the rafts was separated from the dermal equivalent and DNA was extracted using the tissue QIAamp DNA blood minikit (QIAGEN, Basel, Switzerland) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Aliquots of 5 μl of each sample were used in the real-time PCRs.

Quantitative PCR for VZV DNA by Taqman method.

Quantitative PCR was carried out by real-time PCR using the ABI Prism 7000 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

PCR primers for the VZV ORF29 gene (single-stranded DNA binding protein) ORF29-1239F (forward primer: 5′-CCAGTTTGCCGGACCTCAT-3′, nucleotides 1239 to 1257), VZVORF29-1297R (reverse primer: 5′-AGATCGAGATGGCCACGTTC-3′, nucleotides 1278 to 1297) and the Taqman probe (5′-CTG CGA ATC CC-3′, nucleotides 1262 to 1272) dual-labeled at the 5′ end with the reporter dye molecule 6-carboxyfluorsecein (FAM) and the 3′ end with minor groove binder, were designed by the Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Quantitative PCR amplification reactions were set up in a reaction volume of 25 μl using the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Branchburg, NJ), containing 5 μl of purified DNA, 900 nM each of forward primer and reverse primer, and 200 nM of TaqMan probe. Thermal cycling conditions was initiated with a 2-min. incubation at 50°C, followed by a first denaturation step of 10 min at 95°C and then 55 cycles of 95°C for 15 s (denaturation) and 60°C for 1 min (reannealing and extension). Real-time PCR amplification data were collected continuously and analyzed with the sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

For the quantification of VZV DNA, standard curves were constructed by plotting the cycle thresholds (Cts) against the logarithm of the starting amount of serial dilutions of the plasmid standard (pVZV-ORF29) containing the amplified insert. For cloning the pVZV-ORF29 plasmid, a segment of the ORF29 gene was amplified from purified VZV DNA by PCR using the primers described above, and the PCR product was cloned into pCR4-TOPO (TOPO TA Cloning kit, Invitrogen, Groningen, The Netherlands). The sequence of the cloned VZV ORF29 fragment was confirmed by DNA sequencing in both orientations on a capillary DNA sequencing system (Amersham Biosciences). All samples were tested in triplicate, their Cts were determined, and the initial starting sequence amount calculated from standard curves as a mean of the three measurements.

RESULTS

Activity of antiherpesvirus compounds against HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV in PHKs.

The activity of selected antiherpesvirus compounds was first evaluated in monolayers of primary cultures of human keratinocytes (Table 1). Except for BVDU, which is known to lack activity against HSV-2, all compounds proved active against the different viruses tested, the order of increasing activity being PFA < CDV ∼ PCV < BVDU ∼ ACV < GCV for HSV-1, PFA < PCV < CDV < ACV < GCV for HSV-2, and PFA < ACV ∼ PCV < CDV ∼ BVDU for VZV. Although the order of potency was similar to that previously reported by us and others for human embryonic fibroblasts, the compounds appear to be 5- to 20-fold less active in PHKs compared to the values we obtained in human fibroblasts (2, 3).

TABLE 1.

Activity of antiherpesvirus compounds against HSV-1, HSV-2, and VZV in primary human keratinocytes

| Virus | IC50 (μg/ml)a

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACV | PCV | GCV | BVDU | PFA | CDV | |

| HSV-1 (Kos strain) | 0.21 ± 0.11 | 0.61 ± 0.33 | 0.017 ± 0.010 | 0.45 ± 0.47 | 32.3 ± 8.8 | 0.69 ± 0.26 |

| HSV-2 (Lyons strain) | 0.15 ± 0.07 | 1.76 ± 0.34 | 0.077 ± 0.010 | >20 ± 0 | 30.3 ± 6.3 | 0.83 ± 0.82 |

| VZV (Oka strain) | 0.092 ± 0.011 | 0.088 ± 0.063 | N.D. | 0.014 ± 0.016 | 9.4 ± 6.8 | 0.011 ± 0.009 |

IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration or compound concentration required to reduce viral CPE (HSV-1 and HSV-2) or plaque formation (VZV) by 50%. The results are means of two independent experiments. N.D., not determined.

Effect of the time of virus application on organotypic epithelial raft cultures.

Organotypic cultures of human foreskin keratinocytes were infected at various days after lifting the rafts to the air-liquid interface. Virus infection was studied by examination of histological sections after staining with hematoxylin and eosin. In an organotypic raft culture, normal human keratinocytes stratify and form a differentiated epithelium reproducing the different layers of the skin, including orthokeratosis normally present in the skin.

Histological examination of the culture sections showed that infection of the rafts with HSV-1 and HSV-2 produced cytopathic effects, resulting in ballooning and reticular degeneration of the keratinocytes together with the occurrence of intranuclear eosinophilic inclusion bodies, formation of typical intraepithelial vesicles, and multinucleation (Fig. 1 and data not shown). When the raft cultures were infected immediately after lifting the cultures or at 1, 2, 3, or 4 days postlifting, all cells were infected and no formation of epithelium could be seen due to the cytopathic effect of the virus. HSV infection was observed throughout the epithelium when the virus was applied on the surface of a full-thickness epithelium grown for 6 or 8 days. The infection was not limited to a specific layer of the differentiated epithelium; instead, the infection appeared to spread, including the most superficial cell layers. When cultures were infected with either HSV-1 or HSV-2 10 days after lifting and fixed 14 days after lifting, viral cytopathic effects were observed only in the upper layers of the differentiated epithelium (data not shown).

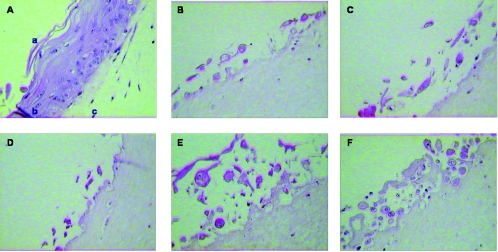

FIG. 1.

Pattern of HSV-1 (KOS strain) infection in cultures infected at day 0 (B), or 2 days (C), 4 days (D), 6 days (E), or 8 days (F) after lifting compared to noninfected cultures (A), where the stratum corneum (a), the well-differentiated epithelium (b) and the collagen matrix with the feeder cells (c) can be seen. Magnification 40.

Infection of the organotypic cultures with either TK+ or TK− VZV strains also led to morphological alterations, including ballooning of the cells (Fig. 2). Similar to HSV infection, the VZV infection spread all along the epithelium, including the most superficial cell layers. However, the aspects of the lesions depended on the stage of differentiation of the cell cultures. The epithelium was completely affected when the virus was inoculated up to 4 days after lifting, while the severity of the infection was reduced when the virus was inoculated after 6 days, and even more so when applied 8 days after lifting. No signs of cytopathic effect were noted if the time of infection was delayed to 10 days after lifting the rafts (data not shown). Infection of the organotypic epithelial raft cultures with a nondermotropic herpesvirus, human cytomegalovirus, did not lead to any morphological signs of infection even if the cultures were infected from the very early stages of differentiation onwards (data not shown).

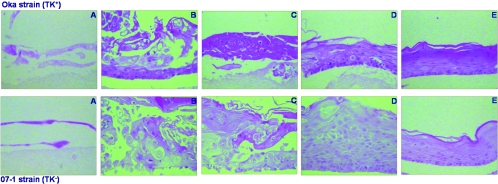

FIG. 2.

Pattern of VZV (OKA and 07-1 strains) infection in cultures infected at day 0 (A), or 2 days (B) 4 days (C), 6 days (D), or 8 days (E) after lifting. Magnification ×40.

Effect of specific antiherpesvirus compounds on viral replication in organotypic epithelial raft cultures.

The ability of specific antiherpesvirus compounds to reduce replication and spread of HSV and VZV in raft cultures of human keratinocytes was determined. Organotypic epithelial raft cultures were infected after 4 to 5 days (VZV) or after 8 days (HSV) of differentiation and treated with serial dilutions of the test compounds. At 12 days postlifting the rafts were processed for histology or viral quantification. Under these experimental conditions, viral infection and spread in nontreated cultures occurred all along the epithelium.

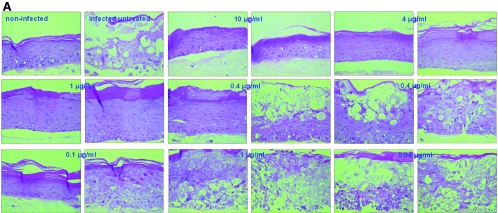

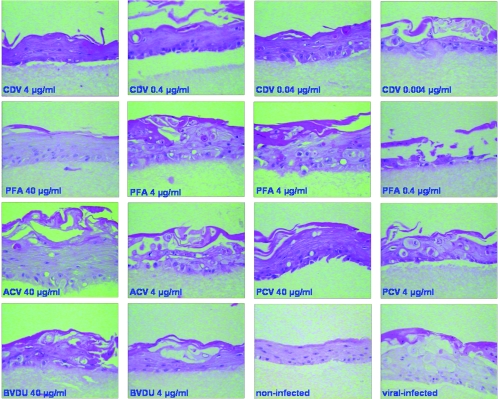

Morphological analysis of the organotypic cultures showed that treatment with ACV and PCV at 10, 4, and 1 μg/ml protected the entire epithelium against HSV-1-induced cytopathic effect (Fig. 3A and Fig. 3B), while at 0.4 μg/ml and 0.1 μg/ml, the compounds afforded partial protection, with areas of the rafts showing a normal epithelium and parts of the rafts completely destroyed due to the replication of the virus. Neither ACV nor PCV was active at a concentration of 0.04 μg/ml. Treatment with CDV at 10, 4, and 1 μg/ml and with PFA at 40 and 10 μg/ml resulted in complete protection of the epithelial tissue, while zones of the rafts with viral cytopathic effects were noted at lower concentrations of the compounds (i.e., 0.4 μg/ml and 0.1 μg/ml of CDV and 4 μg/ml of PFA). No antiviral effect was observed for CDV at 0.04 μg/ml and PFA at 1 μg/ml. In the case of BVDU, although most of the surface of the raft was protected, some areas of viral cytopathic effect were seen at the higher concentrations tested (i.e., 10, 4, and 1 μg/ml), while decreased protection was seen with lower BVDU doses.

FIG. 3.

Effects of ACV (A) and PCV (B) on organotypic epithelial rafts cultures infected with HSV-1 (KOS strain) at 8 days after lifting. Compounds were added to the culture medium on the day of infection and remained in contact with the cells until the rafts were fixed (i.e., at 12 days after lifting).

These compounds were also evaluated against a TK− HSV-1 strain. As expected, CDV and PFA, which do not depend on viral TK for their activation, showed activity against TK− strains in a concentration-dependent manner, while ACV, PCV, and BVDU showed reduced potency. When the compounds were evaluated against HSV-2, BVDU proved inactive against both TK+ and TK− HSV-2 strains due to the inability of the HSV-2 TK to phosphorylate BVDU monophosphate to BVDU diphosphate. A concentration dependent inhibition of viral induced cytopathogenicity was observed with ACV and PCV against HSV-2 wild-type virus and with CDV and PFA against both TK+ and TK− HSV-2 strains (data not shown).

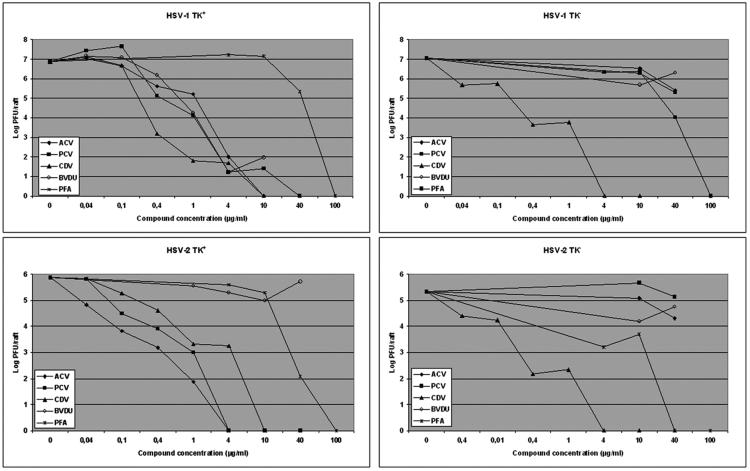

In order to quantify the antiviral effects afforded by the different compounds, the virus yield per raft was determined by plaque assay. As shown in Fig. 4, a concentration-dependent inhibition of viral production per raft was observed following treatment of the rafts with serial concentrations of the compounds, the results being in agreement with inhibition of virally induced cytopathic effects in the rafts. Table 2 shows the IC90 and IC99 values calculated for the different compounds. CDV was equally active against TK+ and TK− HSV strains, with IC90 and IC99 values in the range of 0.04 to 0.33 μg/ml and 0.3 to 0.88 μg/ml, respectively. Foscarnet inhibited the replication of the different HSV strains, with IC90 and IC99 values of <10 to 36.2 μg/ml and 21.5 to 73.7 μg/ml, respectively. ACV and PCV inhibited the replication of TK+ strains with comparable IC90 and IC99 values. Although IC90 and IC99 values for BVDU against the HSV-1 TK+ strain is of the same order as those found for ACV and PCV, full inhibition was not observed at the highest concentrations.

FIG. 4.

Quantification of virus yield in organotypic epithelial raft cultures infected with HSV-1 and HSV-2 TK+ and TK− strains at 8 days postlifting. Compounds were added to the culture medium the day of infection (i.e., 8 days postdifferentiation) and remained in contact with the cells till the rafts were frozen (i.e., at 12 days after lifting) for determination of virus production by plaque assay.

TABLE 2.

Activity of antiherpesvirus compounds in organotypic epithelial raft culturesa

| Compound | HSV-1 TK+

|

HSV-1 TK−

|

HSV-2 TK+

|

HSV-2 TK−

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC90 | IC99 | IC90 | IC99 | IC90 | IC99 | IC90 | IC99 | |

| ACV | 0.36 | 1.87 | 26.82 | >40 | 0.04 | 0.099 | 38.7 | >40 |

| PCV | 0.36 | 0.63 | 18.3 | >40 | 0.094 | 0.44 | 37.8 | >40 |

| BVDU | 0.64 | 0.97 | >40 | >40 | >40 | >40 | 32.3 | >40 |

| CDV | 0.33 | 0.39 | ≤0.04 | 0.3 | 0.30 | 0.88 | 0.054 | 0.34 |

| PFA | 36.2 | 73.68 | 20.5 | 37.63 | 14.15 | 36.12 | <10 | 21.5 |

The activity of the compounds is expressed as the concentration of compound (μg/ml) required to reduce virus yield production per raft by 90% (IC90) or 99% (IC99) compared to untreated cultures.

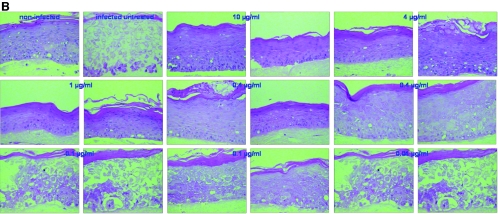

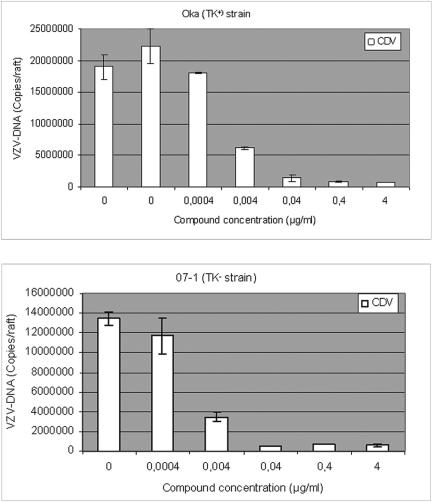

When the different compounds were assessed against VZV, ACV, PCV, and BVDU inhibited the replication of the Oka strain (TK+) but not of the 07-1 strain (TK−) in the rafts in a dose-dependent manner, while CDV and PFA proved equally active against both strains (Fig. 5 and data not shown). The antiviral effects on rafts infected with VZV and treated with serial concentrations of the compounds were determined by measuring viral DNA by real-time PCR. As shown in Fig. 6, CDV at concentrations of 4, 0.4, and 0.04 μg/ml decreased viral copy numbers significantly, while lower concentrations were inactive, which is in agreement with histological examination of the rafts. ACV and PCV were able to decrease the viral DNA load in rafts infected with the Oka strain but not with the TK− strain 07-1 (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Effects of different antiviral compounds on organotypic epithelial raft cultures infected with 07-1 TK− strain at 5 days after lifting. Compounds were added to the culture medium the day of infection and remained in contact with the cells until the rafts were fixed (i.e., at 12 days after lifting).

FIG. 6.

Quantification of VZV-DNA by real-time PCR in organotypic epithelial raft cultures infected with Oka (TK+) or 07-1 (TK−). Cidofovir was added to the culture medium the day of infection (5 days postdifferentiation) and remained in contact with the cells till the epithelium was harvested and DNA isolated (i.e., at 12 days after lifting).

It should be noted that no toxic effects, measured as an increase in the number of dead cells or alteration of differentiation, were observed at the highest concentrations of the compounds tested.

DISCUSSION

We describe here a novel model for the study of antiviral compounds against HSV and VZV at the tissue level. We have used a three-dimensional epithelial culture system which promotes the differentiation of human keratinocytes. In HSV- and VZV-infected organotypic epithelial raft cultures, we observed cytopathic changes identical to those found in the squamous epithelium in vivo, including the formation of typical intraepithelial vesicles and multinucleation. The histological characteristics of HSV and VZV lesions are well known and have been carefully described in the past. For example, changes induced by HSV infection of the skin include ballooning of infected cells followed by subsequent degeneration of the cellular nuclei, generally within parabasal and intermediate cells of the epithelium. The cells lose intact plasma membranes and evolve to multinucleated giant cells. Upon cell lysis, clear fluid containing large quantities of virus accumulates between the epidermis and dermal layer and forms vesicles (26). Characteristic histological changes of VZV infection include balloon degeneration of infected cells, with the formation of intranuclear inclusions and multinuclear giant cells. Affected cells have marginated chromatin. Early in the course of infection, the nuclei may contain homogenous basophilic material, but more often they show a rounded eosinophilic body surrounded by a wide clear zone. Multinucleated giant cells may contain up to 30 nuclei, each with an inclusion body (9). Similar cells are seen in herpes zoster and HSV infections, but not in vesicular lesions produced by poxviruses or enteroviruses.

Compounds known for their activity against HSV and VZV, e.g., ACV, PCV, BVDU, PFA, and CDV (8, 21, 28), were tested in monolayers of PHKs and in organotypic epithelial raft cultures. Antiviral assays in monolayers of PHKs, showed that IC50 values obtained in PHKs were higher than those we have previously reported for human embryonic fibroblasts. Differences in drug susceptibility profiles for HSV among different cell lines have been reported previously (1, 7, 13). ACV, BVDU, PCV, and GCV depend on phosphorylation by the viral TK for their activation; therefore, when ACV, PCV, and BVDU were tested in the organotypic epithelial raft culture system, they proved active only against TK+ strains, while PFA and CDV, which do not require phosphorylation by the viral TK, proved active against both TK+ and TK− strains.

The antiviral effects of the different compounds in the organotypic raft cultures were quantified by measuring viral titers by plaque assay for HSV and viral DNA load by real-time PCR for VZV. To release the infectious virus from the rafts, HSV-infected organotypic cultures were frozen and thawed and virus yield per raft was determined. Due to the strong association of VZV with the cells, the virus could not be released after freezing and thawing of the epithelium; therefore, the DNA was isolated from the epithelium and the VZV-DNA was quantified by real-time PCR. For the different compounds we showed a correlation between inhibition of viral replication as determined by virus yield (for HSV) or viral DNA (for VZV) and inhibition of viral cytopathicity as determined by histology of the sections.

In the present study, the antiviral compounds were delivered by addition to the culture medium; therefore, the drugs are entering the rafts from what could be considered the equivalent of the basal membrane. Thus, the basal delivery of the compounds might mimic a systemic delivery route with diffusion into the dermis. Experiments are currently under way to adapt the organotypic epithelial raft culture system as a model to mimic topical delivery of compounds via application of drugs to the top of the epithelium.

HSV and VZV belong to the alphaherpesvirus group, based on their neurotropism, and they are characterized by their ability to establish latency and recur over time. The incidence of HSV and VZV infections is high throughout the world. According to serological studies, HSV-1 and VZV affect up to 90% of the population. For HSV infections, recurrent herpes labialis and genital infection are exceedingly common. In contrast, shingles due to recurrent VZV infection occurs with increased frequency over a lifetime and is more prominent in immunocompromised patients.

Varicella, the primary infection caused by VZV, is characterized by viremia and skin lesions. The critical events in the pathogenesis of primary VZV infection include involvement of the respiratory mucosa, occurrence of cell-associated viremia, and transfer of infectious virus to skin, resulting in the characteristic vesicular exanthema. T lymphocytes appear to be a major target cell for VZV viremia, and these migrating cells are responsible for transport of the virus from the respiratory epithelial inoculation sites to dermal and epidermal cells (4, 5, 12). VZV skin lesions contain high titers of infectious virus, which is transmissible to other susceptible individuals in the population. Thus, T cells as well as the skin can be considered critical targets for VZV pathogenesis. However, the cells generally used for culturing VZV and for testing antiviral agents, are human fibroblasts.

Human epithelial cells appear to be a more relevant system than fibroblasts for the study of VZV pathogenesis and evaluation of antiviral compounds. Moreover, the development of an ex vivo system, such as the organotypic epithelial raft culture, for the study of VZV pathogenesis is important, considering the lack of a simple small-animal model which mimics human disease. The SCID-hu mouse implanted with human fetal tissue is the only model available for studying VZV pathogenesis in vivo (17, 18).

VZV has been shown to be able to infect and replicate in cultures of human keratinocytes derived from different sources (19). We demonstrated in the present study the ability of VZV to infect not only monolayers of human keratinocytes isolated from neonatal foreskins, but also epithelium. It should be noted that the susceptibility of the organotypic epithelial raft cultures to infection with VZV depends on the stage of differentiation of the raft, i.e., with the time the rafts are lifted to induce differentiation. Since cell-associated virus is used to infect the rafts, it is possible that the infected cells are not able to adhere and infect the rafts once the epithelium shows signs of differentiation. The raft cultures represent a novel approach for investigating VZV replication in epidermal cells undergoing differentiation.

HSV infects keratinocytes, where it replicates and spreads from cell to cell, establishing a primary infection and infecting sensory neurons (26, 27). HSV then travels along peripheral sensory nerves and reaches the associated ganglion, where the virus becomes latent within the neuron nucleus. Reactivation of the virus leads to replication in the ganglion and transport of infectious virus along peripheral sensory nerves to the epidermis near the primary site of infection, with subsequent production of secondary lesions. Evidently, the ability of the virus to spread between keratinocytes and between epidermal and neuronal cell populations is central to the pathogenesis of the virus.

The applicability of the organotypic epithelial raft cultures to the study of HSV has been reported previously (10, 24, 25). In these studies a productive HSV-1 infection was established with morphological characteristics of herpes lesions in vivo. However, differences in virus spread and the course of infection were observed among these studies. Syrjänen et al. (24) and Hukkanen et al. (10) obtained HSV-1 infection throughout the whole epithelium only when the cells were infected before lifting, whereas Visalli et al. (25) found a productive infection with HSV-1 in the basal and parabasal cells of the epithelium. The latter group used foreskin and ectocervical keratinocytes as the source of epithelial cells and mouse 3T3 cells as feeders, while Syrjänen et al. (24) and Hukkanen et al. (10) used a spontaneously transformed HaCat keratinocyte cell line as the source of epithelial cells and human fibroblasts derived from skin as feeder cells. In the present studies we have used normal keratinocytes derived from human neonatal foreskins and mouse fibroblasts (a slowly growing clone derived from mouse 3T3 cells) as feeder cells, and our results clearly show that infection with either HSV-1 or HSV-2 on the surface of the lifted epithelium occurs throughout the different layers of the skin.

The discrepancies with the studies reported previously may be due to the type of murine fibroblasts used as feeders, the degree of maturation and proliferation of the epithelium produced, and the virus inoculum used for the viral infection. It should be noted that the organotypic epithelial raft cultures used in the present study reproduce a normal, well-differentiated epithelium where the different layers of the skin (i.e., stratum corneum with keratin production, stratum granulosum, stratum spinosum, and stratum basale or stratum germinativum) could be distinguished. Also, we used a higher virus inoculum per raft than reported in the previous studies. It should also be mentioned that for both HSV and VZV, the cytopathic effects of TK+ and TK− strains did not differ (Fig. 2 and data not shown). Also, virus titers (for HSV) or viral DNA load (for VZV) per raft were similar in TK+ and TK− strain-infected organotypic cultures, showing no sign of attenuation under these experimental conditions for the TK− strains.

Although the organotypic epithelial raft culture is an expensive and time-consuming model to work with, we showed the feasibility of using this system for the evaluation of antiherpesvirus compounds. Furthermore, this system can be very useful for the study of the interactions of viruses with the skin. No significant variability in differentiation between rafts of the same experiment was seen, and the activity of the compounds has been confirmed in independent experiments (data not shown).

In summary, infection of organotypic epithelial raft cultures with HSV and VZV on top of the lifted epithelium resulted in typical cytopathic effects throughout the thickness of the epithelium. We have shown that the three-dimensional epithelial raft culture represents a novel approach for the study of antiviral agents active against HSV and VZV.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Fund for Scientific Research Flanders (FWO-Vlaanderen) (G-0267-04) and the Belgian Geconcerteerde Onderzoeksacties (GOA) (2005/19).

We thank C. Callebaut for her fine editorial help and Anita Camps, Lies Van Den Heurck, Ilse Van Aelst, and Steven Carmans for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andrei, G., R. Snoeck, and E. De Clercq. 1994. Human brain tumor cell lines as cell substrates to demonstrate sensitivity/resistance of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 to acyclic nucleoside analogues. Antiviral Chem. Chemother. 5:263-270. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrei, G., R. Snoeck, E. De Clercq, R. Esnouf, P. Fiten, and G. Opdenakker. 2000. Resistance of herpes simplex virus type 1 against different phosphonylmethoxyalkyl derivatives of purines and pyrimidines due to specific mutations in the viral DNA polymerase gene. J. Gen. Virol. 81:639-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrei, G., R. Sienaert, C. McGuigan, E. De Clercq, J. Balzarini, and R. Snoeck. 2005. Susceptibilities of several clinical varicella-zoster virus (VZV) isolates and drug-resistant VZV strains to bicyclic furanopyrimidine nucleosides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1081-1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arvin, A. M. 2001. Varicella-zoster virus, p. 2731-2767. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed., vol. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Besser, J., M. Ikoma, K. Fabel, M. H. Sommer, L. Zerboni, C. Grose, and A. M. Arvin. 2004. Differential requirements for cell fusion and virion formation in the pathogenesis of varicella-zoster virus infection in skin and T cells. J. Virol. 78:13293-13305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chow, L. T., and T. Broker. 1997. In vitro experimental systems for HPV: epithelial raft cultures for investigations of viral reproduction and pathogenesis and for genetic analyses of viral proteins and regulatory sequences. Clin. Dermatol. 15:217-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Clercq, E. 1982. Comparative efficacy of antiherpes drugs in different cell lines. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 21:661-663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Clercq, E. 2003. Clinical potential of the acyclic nucleoside phosphonates cidofovir, adefovir, and tenofovir in treatment of DNA virus and retrovirus infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 16:569-596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelb, L. D. 1993. Varicella-zoster virus: clinical aspects, p. 281-308. In B. Roizman, R. J. Whitley, and C. Lopez (ed.), The human herpesviruses. Raven Press, Ltd., New York, NY.

- 10.Hukkanen, V., H. Mikola, M. Nykänen, and S. Syrjänen. 1999. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection has two separate modes of spread in three-dimensional keratinocyte culture. J. Gen. Virol. 80:2149-2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung, B. F., R. W. Johnson, D. R. Griffin, and R. H. Dworkin. 2004. Risk factors for postherpetic neuralgia in patients with herpes zoster. Neurology 62:1545-1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ku, C. C., J. A. Padilla, C. Grose, E. C. Butcher, and A. M. Arvin. 2002. Tropism of varicella-zoster virus for human tonsillar CD4+ T lymphocytes that express activation, memory, and skin homing markers. J. Virol. 76:11425-11433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leary, J. J., R. Wittrock, R. T. Sarisky, A. Weinberg, and M. J. Levin. 2002. Susceptibilities of herpes simplex viruses to penciclovir and acyclovir in eight cell lines. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:762-768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyers, C., and L. A. Laimins. 1994. In vitro systems for the study and propagation of human papillomaviruses. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 186:199-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyers C., M. Mane, N. Kokorina, S. Alam, and P. L. Hermonat. 2000. Ubiquitous human adeno-associated virus type 2 autonomously replicates in differentiating keratinocytes of a normal skin model. Virology 272:338-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyers, C., S. S. Andreansky, and R. J. Courtney. 2003. Replication and interaction of herpes simplex virus and human papillomavirus in differentiating host epithelial tissue. Virology 315:43-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moffat, J. F., M. D. Stein, H. Kaneshima, and A. M. Arvin. 1995. Tropism of varicella-zoster virus for human CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes and epidermal cells in SCID-hu mouse. J. Virol. 69:5236-5242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moffat, J. F., L. Zerboni, P. R. Kinchington, C. Grose, H. Kaneshima, and A. M. Arvin. 1998. Attenuation of the vaccine Oka strain of varicella-zoster virus and role of glycoprotein C in alphaherpesvirus virulence demonstrated in the SCID-hu mouse. J. Virol. 72:965-974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sexton, C. J., H. A. Navsaria, I. M. Leigh, and K. Powell. 1992. Replication of varicella-zoster virus in primary human keratinocytes. J. Med. Virol. 38:260-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snoeck R., G. Andrei, M. Gerard, A. Silverman, A. Hedderman, J. Balzarini, C. Sadzot-Delvaux, G. Tricot, N. Clumeck, N., and E. De Clercq. 1994. Successful treatment of progressive mucocutaneous infection due to acyclovir- and foscarnet-resistant herpes simplex virus with (S)-1-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)cytosine (HPMPC). Clin. Infect. Dis. 18:570-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snoeck, R., G. Andrei, and E. De Clercq. 1999. Current pharmacological approaches to the therapy of varicella zoster virus infections: a guide to treatment. Drugs 57:187-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snoeck, R., A. Holý, C, C. Dewolf-Peeters, J. Van den Oord, E. De Clercq, and G. Andrei. 2002. Antivaccinia activities of acyclic nucleoside phosphonate derivatives in epithelial cells and organotypic cultures. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3356-3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stankus, S. J., M. Dlugopolski, and D. Packer. 2000. Management of herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Am. Fam. Physician 61:2437-2448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Syrjänen, S., H. Mikola, M. Nykänen, and V. Hukkanen. 1996. In vitro establishement of lytic and nonproductive infection by herpes simplex virus type 1 in three-dimensional keratinocyte culture. J. Virol. 70:6524-6528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Visalli, R. J., R. J. Courtney, M. Nykänen, and V. Hukkanen. 1997. Infection and replication of herpes simplex virus type 1 in an organotypic epithelial culture system. Virology 230:236-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitley, R. J., and J. W. Gnann, Jr. 1993. The epidemiology and clinical manifestations of herpes simplex virus infections, p. 69-105. In B. Roizman, R. J. Whitley, and C. Lopez (ed.), The human herpesviruses. Raven Press, Ltd., New York, NY.

- 27.Whitley, R. J. 2001. Herpes simplex viruses, p. 2461-2509. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed., vol. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wutzler, P. 1997. Antiviral therapy of herpes simplex and varicella-zoster virus infections. Intervirology 40:343-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]