Abstract

The antibacterial activity of human neutrophil defensin HNP-1 analogs without cysteines has been investigated. A peptide corresponding to the HNP-1 sequence without the six cysteines (HNP-1ΔC) exhibited antibacterial activity toward gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. Truncated analogs wherein the nine N-terminal residues of HNP-1 and the remaining three cysteines were deleted (HNP-1ΔC18) or the G was replaced with A (HNP-1ΔC18A) also exhibited antibacterial activity. Substantial activity was observed for HNP-1ΔC and HNP-1ΔC18 in the presence of 100 mM NaCl, except in the case of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The linear peptides were active in the presence of carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), indicating that proton motive force was not essential for killing of bacteria by the peptides. In fact, in the presence of CCCP, the peptides were active against P. aeruginosa even in the presence of 100 mM NaCl. The antibacterial activity of HNP-1ΔC, but not that of the shorter, 18-residue peptides, was attenuated in the presence of serum. The generation of defensins without cysteines would be easier than that of disulfide-linked defensins. Hence, linear defensins could have potential as therapeutic agents.

Mammalian defensins are a family of cationic antimicrobial peptides characterized by three disulfide bridges (13, 22, 35). They are expressed in granulocytes, monocytes, macrophages, and epithelial cells of the skin, intestines, and other tissues (2, 13, 39). Based on the pattern of disulfide bonding, mammalian defensins have been classified into α and β families. In another class named the θ-defensins, in addition to three disulfide bridges, the amino- and carboxyl-terminal ends are linked via an amide bond (13). In humans, α-defensins are produced in neutrophils and Paneth cells of the small intestine, while β-defensins are expressed by epithelial cells at various sites (13, 22). The θ-defensins have been identified only in primates (13, 19). The expression of defensins is constitutive as well as induced by infection and inflammation (13, 22, 23). Defensin biosynthesis and release have been observed to be regulated by microbial signals, developmental signals, and cytokines (13, 14). Apart from their role as microbicidal agents, defensins have also been implicated as effective immune modulators in adaptive immunity (11, 54). They have potency to enhance phagocytosis, induce the activation and degranulation of mast cells, and indirectly regulate innate antimicrobial immunity by affecting the production of chemokines such as interleukin-8, interleukin-10, and tumor necrosis factor from different cells (3, 24, 53). Studies have also revealed the role of defensins in adaptive immunity, as reflected by their chemotactic effect on monocytes, T cells, and immature dendritic cells (5, 32, 35, 43, 48, 54).

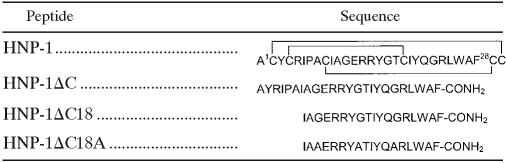

Human neutrophil defensins (HNP-1 to HNP-4) are stored in azurophilic granules of the neutrophil. They are transferred to phagolysosomes upon phagocytosis to kill the ingested microbes (14, 15). The crystal structure of HNP-3 reveals a dimeric structure, with each monomer containing a triple-stranded β-sheet region (16). Nuclear magnetic resonance studies indicate that HNP-1 also forms dimers or higher-order aggregates in solution. The three β-strands observed in HNP-3 are also present (34, 57). In an effort to determine how essential the disulfide connections are for antibacterial activity and structure, we have investigated the antibacterial activity of a peptide spanning residues A1 to F28 of HNP-1 which does not have the six cysteines present in HNP-1 (Table 1). We have also examined the effect of deleting the amino acids AYRIPA from the N-terminal end of this peptide and the effect of replacing G with A in the truncated analog (Table 1) on antibacterial activity and structure.

TABLE 1.

Primary structure of HNP-1 and its analogs

MATERIALS AND METHODS

9-Fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl (F-moc) amino acids were obtained from Novabiochem AG (Switzerland) and Advanced Chemtech (Louisville, KY). The F-moc amide handle crown was from Mimotopes (Australia). 1-N-Phenyl naphthylamine (NPN) and carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) were obtained from Sigma. All other chemicals used were of the highest grade available.

Peptide synthesis.

Peptides were synthesized using an F-moc amide handle crown employing F-moc chemistry (1). The synthesized peptides were cleaved and deprotected by using a mixture containing 82.5% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), 5% phenol, 5% H2O, 5% thioanisole, and 2.5% ethanedithiol for 12 to 15 h at room temperature. HNP-1 was synthesized on 4-hydroxymethylphenoxymethyl resin (Applied Biosystems; 0.9 mmol/g) (28) with the cysteines protected by acetamidomethyl (46). The removal of acetamidomethyl was effected by Hg(II) acetate and β-mercaptoethanol treatment (28, 46) followed by gel filtration on a Biogel P-2 column. HNP-1 was then oxidized in 20% dimethyl sulfoxide-water (42) at a peptide concentration of 0.2 to 0.4 mM. This was followed by gel filtration with 50% acetonitrile-water containing 0.01% TFA. The peptides were purified on a Hewlett-Packard 1100 series high-performance liquid chromatography instrument with a reversed-phase C4 or C18 Bio-Rad column. The solvents consisted of 0.1% TFA in H2O as mobile phase A and 0.1% TFA in CH3CN as mobile phase B. The purified peptides were then characterized by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry on a Voyager DE STR mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems) at the Proteomics Facility of the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology. Stock solutions of HNP-1 analogs were prepared by dissolving the peptides in water. A stock solution of HNP-1 was prepared in 0.01% acetic acid. The concentrations were determined by monitoring the absorbance of tryptophan at 280 nm.

Antibacterial activity.

The bacterial strains used were Escherichia coli W 160-37 (47), Staphylococcus aureus (NCTC 8530), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (NCTC 6750). Bactericidal activity was determined as follows. Mid-log-phase bacteria were obtained by growing bacteria in nutrient broth (Bacto; Difco), washing them twice with 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and then diluting them in the same buffer to give approximately 106 CFU/ml. A final volume of 100 μl was used in sterile 96-well plates to examine the antibacterial activity of the peptides. After incubation of the bacteria with different concentrations of peptides for 2 h at 37°C, 20 μl was plated on nutrient agar plates. The plates were incubated for 18 h at 37°C, and the colonies formed were counted. The lowest concentration of peptide at which there was complete killing was taken as the lethal concentration (LC). In control experiments, cells were incubated with only 0.01% acetic acid (the solvent used to dissolve HNP-1).

Kinetics of bacterial killing.

The kinetics of bacterial killing were determined against gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. Mid-log-phase bacteria (105 CFU/ml) were incubated with LCs of peptides in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) in a final volume of 100 μl. Aliquots of 20 μl were removed at fixed intervals and plated on nutrient agar plates. The CFU were counted after an incubation of 16 to 18 h at 37°C. The values mentioned in the results are the averages of two independent experiments.

Salt sensitivity.

Salts (NaCl, 100 mM; MgCl2 and CaCl2, 1 mM and 2 mM) were added to the incubation buffer to examine the effect of salt on the antibacterial activity of the peptides. The effect of salts was examined at the lethal concentrations of the peptides. E. coli MG1655 (105 CFU/ml) was used to examine inhibition by MgCl2 and CaCl2. The values determined were the averages of three independent experiments. The variation was within ±5%.

Outer membrane permeabilization assay.

The ability of peptides to permeabilize the outer membranes of E. coli MG 1655 cells was investigated using an NPN uptake assay (25, 38). Briefly, cells at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 were suspended in 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) with 10 μM NPN. After 15 min of incubation, peptides were added, and the fluorescence of NPN was monitored. The excitation wavelength used was 350 nm, and the emission wavelength was 420 nm. The experiment was carried out at 25°C.

Inner membrane permeabilization assay.

The ability of peptides to permeabilize the inner membranes of bacteria was studied using E. coli GJ 2455 (lacI lacZ+ strain derived from E. coli MG1655 at Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology), which constitutively expresses β-galactosidase in its cytoplasm. o-Nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) was used as the substrate for β-galactosidase. Late-logarithmic-phase (OD600, 0.5 to 0.6) cells were washed and diluted to an OD600 of 0.03 in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and 0.53 mM ONPG was added. After the addition of different peptide concentrations, OD measurements were made every 5 min at 550 nm and 420 nm, and absorbance calculations [A420 − (1.75 × A550)] were taken as a measure of the β-galactosidase activity. The production of o-nitrophenol was monitored at 420 nm. The value 1.75 × A550 represents the light scattering by cell debris at 420 nm. Bacterial cells without any peptide were used as a control.

Effect of dissipation of proton motive force on antibacterial activity.

The effect of a loss of proton motive force due to the action of CCCP was examined as follows. Bacteria were preincubated with 20 μM CCCP for 20 min, followed by the addition of peptides at the LC, with or without NaCl. The effect of incubation with 50 μM CCCP was also examined. CCCP at concentrations of 20 μM and 50 μM has been used for dissipation of the proton motive force in bacteria (10, 33, 40). The bactericidal activity was determined as described earlier. The values determined were the averages of three independent experiments. The variation was within ±5%.

Hemolytic activity.

Human erythrocytes were used to evaluate the hemolytic activity of the peptides. Erythrocytes were obtained by centrifuging (800 × g) heparinized blood and then were washed thrice with 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM NaCl. Aliquots containing 107 red blood cells/ml were incubated in the presence of different peptide concentrations in 0.5-ml Eppendorf tubes at a final volume of 100 μl for 30 min at 37°C with gentle mixing. The tubes were centrifuged, and the absorbance of the supernatants was measured at 540 nm. Erythrocyte lysis occurring in distilled water was taken as maximal lysis.

Serum sensitivity assay.

To study the effect of serum components on the antimicrobial activity and hemolytic activity of the peptides, serum was isolated from human blood after the removal of erythrocytes by centrifugation. Total protein was estimated using the Folin-Ciocalteu-Lowry method (26). For both antimicrobial activity and hemolytic activity, serum at 1 mg/ml was included in the buffer and incubated for 15 min before the addition of peptides. Cells with only serum were used as a control.

Circular dichroism (CD).

A JASCO J-715 spectropolarimeter was used to record the spectra of peptides in water, trifluoroethanol (TFE), and 10 mM sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at 25°C. A quartz cell with a 1-mm path length was used. Spectra were recorded in the region from 195 to 250 nm. The concentrations of peptides were 25 μM for HNP-1ΔC, 30 μM for HNP-1ΔC18, and 20 μM for HNP-1ΔC18A.

RESULTS

Antibacterial activity of peptides.

The ability of the linear peptides and HNP-1 to kill both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria was investigated. The lethal concentrations for killing E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus are shown in Table 2. The results indicate that HNP-1 analogs which lack cysteines, and hence the disulfide cross-links, can still display significant antibacterial activity. However, HNP-1 exhibited greater activity than the analogs. The deletion of AYRIPA from HNP-1ΔC resulted in the attenuation of antibacterial activity. The replacement of G by A in HNP-1ΔC18 marginally increased the potency against E. coli.

TABLE 2.

Antibacterial activity of peptides

| Bacterium | Lethal concentration (μM)a of peptide

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HNP-1 | HNP-1ΔC | HNP-1ΔC18 | HNP-1ΔC18A | |

| E. coli W 160-37 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 14.0 ± 2.0 | 19.0 ± 3.0 | 14.0 ± 2.0 |

| P. aeruginosa NCTC 6750 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 14.0 ± 2.0 | 23.0 ± 3.0 | 23.0 ± 3.0 |

| S. aureus NCTC 8530 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 7.0 ± 2.0 | 10.0 ± 2.0 | 9.0 ± 2.0 |

The values reported for the analogs are means ± maximum variations observed in three independent experiments.

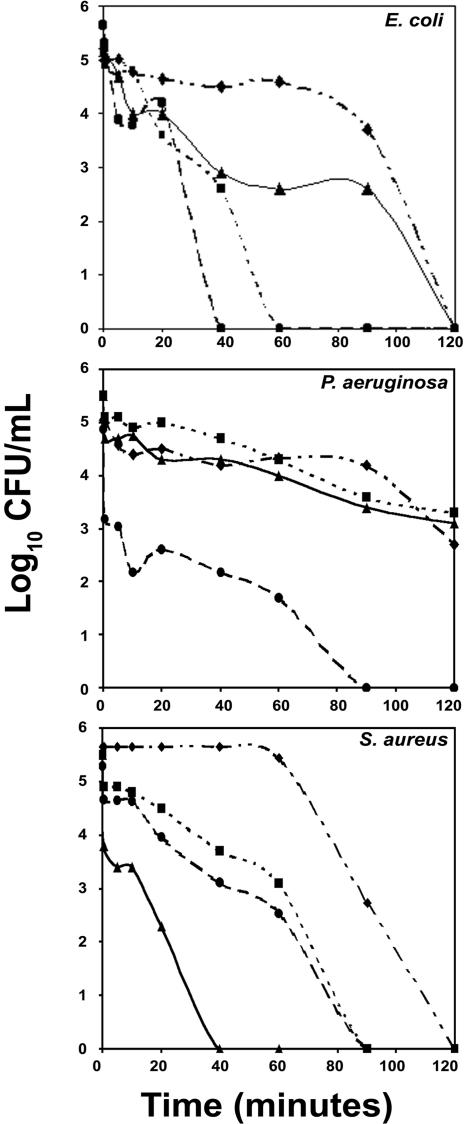

Bacterial killing (reduction in log10 CFU/ml) as a function of time at the LC is shown in Fig. 1. HNP-1ΔC killed E. coli, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa more rapidly than HNP-1. The shorter analogs also killed E. coli and S. aureus more rapidly than HNP-1. However, the rates of killing of P. aeruginosa by the 18-residue peptides and HNP-1 were comparable. Rapid killing of S. aureus by HNP-1ΔC18A compared to that by the other peptides was observed.

FIG. 1.

Kinetics of bacterial killing. Symbols: ⧫, HNP-1; •, HNP-1ΔC; ▪, HNP-1ΔC18; and ▴, HNP-1ΔC18A. Mid-log-phase bacteria (105 CFU/ml) were incubated with peptides at their lethal concentrations.

Effect of salt and serum on antimicrobial activity.

The effects of NaCl on the activities of HNP-1 and its analogs are summarized in Table 3. The activity of HNP-1ΔC was marginally lower against E. coli and S. aureus but decreased considerably against P. aeruginosa. The shorter peptides exhibited relatively greater losses in activity against E. coli. When G was replaced by A in HNP-1ΔC18, the loss in activity against P. aeruginosa and S. aureus was relatively less.

TABLE 3.

Effect of NaCl and human serum on antibacterial activity of peptides

| Bacterium | % Bacterial killing in presence of NaCl (in presence of human serum)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HNP-1 | HNP-1ΔC | HNP-1ΔC18 | HNP-1ΔC18A | |

| E. coli W 160-37 | 68 (50) | 81 (47) | 68 (100) | 59 (100) |

| P. aeruginosa NCTC 6750 | 45 (0) | 10 (13) | 12 (87) | 41 (98) |

| S. aureus NCTC 8530 | 33 (0) | 92 (24) | 63 (99) | 84 (99) |

Mid-log-phase bacteria (105 CFU/ml) were incubated with the LCs of peptides in the presence of 100 mM NaCl. The values in parentheses correspond to the effect of human serum on antibacterial activity in the absence of NaCl. Peptides were used at their LCs and were added after 15 minutes of incubation with 1 mg/ml of serum. The values reported are the averages of three independent experiments. The variation was within ±5%.

When the effects of divalent cations on HNP-1 and its analogs were examined, there was a complete loss of antibacterial activity in the presence of 1 mM MgCl2 for the analogs, unlike HNP-1, which was active even in the presence of 2 mM MgCl2 (data not shown). However, the presence of 2 mM CaCl2 seemed to have only a marginal effect on the antibacterial activity of the three linear analogs toward E. coli MG1655. A complete loss in the activity of HNP-1 was observed in the presence of Ca2+ (data not shown), as reported earlier (20). Both Mg2+ and Ca2+ bind to lipopolysaccharides and stabilize the outer membrane of E. coli (45). Our results suggest that there could be differences in affinity between the linear analogs and HNP-1 for lipopolysaccharides.

The antibacterial activities of the 18-residue peptides were not affected in the presence of serum (Table 3, values in parentheses). HNP-1 and HNP-1ΔC showed reduced activities against E. coli. While HNP-1 was rendered inactive against P. aeruginosa and S. aureus, HNP-1ΔC showed a considerably reduced activity (Table 3).

Outer and inner membrane permeabilization assays.

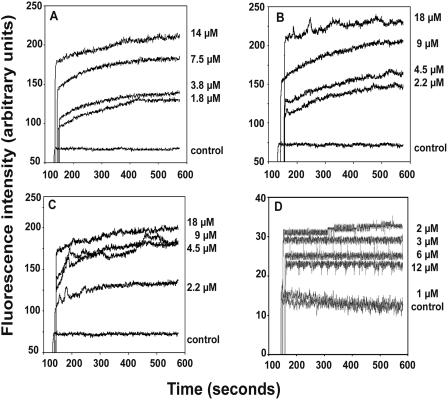

Defensins are known to act by sequentially permeabilizing the outer and inner membranes of E. coli (20). NPN, a neutral hydrophobic probe, has been used to examine the permeabilization of the outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria (38). All of the analogs permeabilized the outer membrane of E. coli in a concentration-dependent manner, as observed by an increase in NPN fluorescence (Fig. 2), despite differences in the inhibition of antibacterial activity by Mg2+ and Ca2+ between HNP-1 and the linear analogs.

FIG. 2.

Outer membrane permeabilization of E. coli MG 1655 by HNP-1 and its analogs. (A) HNP-1ΔC; (B) HNP-1ΔC18; (C) HNP-1ΔC18A; (D) HNP-1. Permeabilization of the outer membrane was monitored as an increase in NPN fluorescence intensity in the presence of various concentrations of peptides, as indicated adjacent to the traces.

When the ability of the peptides to permeabilize the inner membrane of E. coli was examined by the ONPG assay (21), no influx of ONPG was observed, suggesting that the peptides do not permeabilize the inner membrane (data not shown), unlike HNP-1, which was effective in permeabilizing the inner membrane.

Effect of dissipation of proton motive force on antibacterial activity.

The effect of depolarizing the bacterial inner membrane with CCCP on the antibacterial activity of the peptides was examined. HNP-1 and its analogs exhibited bactericidal activities against E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus at their LCs in the absence of a proton motive force as a result of adding 20 μM CCCP. Similar results were observed when 50 μM CCCP was used (data not shown). The peptides were effective against P. aeruginosa in the absence of a proton motive force, even in the presence of 100 mM NaCl (data not shown).

Lysis of human erythrocytes.

The ability of the peptides to lyse human red blood cells is shown in Table 4. For comparable concentrations of peptides, maximum hemolysis was observed with HNP-1ΔC18A, which was, however, neutralized in the presence of human serum.

TABLE 4.

Hemolytic activity of peptides

| Concn of peptide (μM) | % Hemolysis by peptidea

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HNP-1 | HNP-1ΔC | HNP-1ΔC18 | HNP-1ΔC18A | |

| 20 | 15 | 20 | 9 | 21 |

| 40 | 20 | 36 | 14 | 63 |

Erythrocytes (107 cells/ml) were incubated with peptides in 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM NaCl. The values reported are the averages of three independent experiments. The variation was within ±5%.

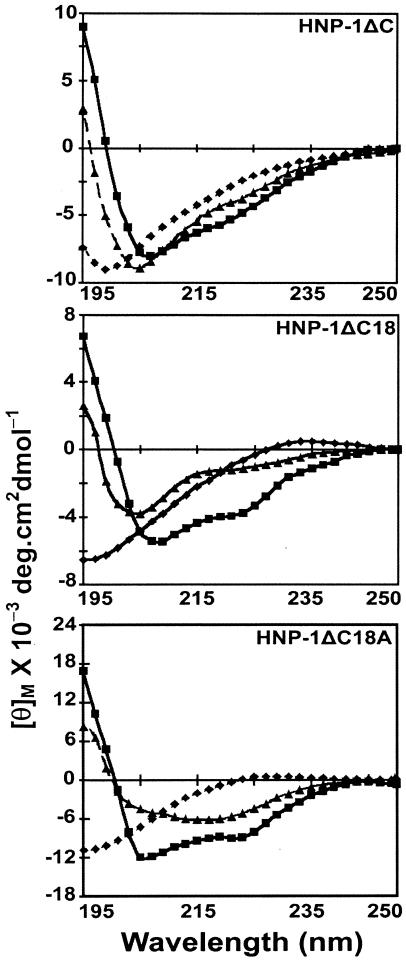

Conformation of peptides.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy was carried out for all three peptides in water, undiluted TFE, and 10 mM SDS (Fig. 3). The spectra of the peptides in water are characteristic of unordered conformations. The spectra of HNP1ΔC in TFE and SDS suggest a population with a β-hairpin conformation (4, 6, 18) characterized by a negative ellipticity near 205 nm and a crossover at ∼200 nm. In TFE, both the HNP-1ΔC18 and HNP-1ΔC18A spectra display minima at ∼205 nm and ∼223 nm, with a crossover at ∼200 nm. The spectra indicate the presence of populations with both β-hairpin and helical conformations (4, 6, 18). In 10 mM SDS, HNP-1ΔC18A shows a minimum at ∼214 nm and a crossover at ∼200 nm, which may indicate a population largely consisting of a β-structure.

FIG. 3.

CD spectra of HNP-1 analogs. CD spectra were measured in water (⧫), TFE (▪), and SDS (▴).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have examined the antibacterial activities of linear peptides derived from the HNP-1 sequence without cysteines. The linear analogs of HNP-1 do possess antibacterial activity, although their lethal concentrations are approximately 10- to 20-fold higher than that of HNP-1.

The antibacterial activities exhibited by HNP-1ΔC18 and HNP-1ΔC18A suggest that the six N-terminal amino acids AYRIPA present in HNP-1 are dispensable for activity, even in the context of the linear sequence. It was shown earlier that peptides derived from the HNP-1 sequence without AYRIPA, but constrained by one or two disulfide bridges, have antibacterial activity (28). The residue G does not appear to play a crucial structural role, as its replacement with A does not diminish the activity. CD data indicate that linear HNP-1ΔC does tend to adopt a β-structure, suggesting that there is an intrinsic propensity of the peptide sequence to adopt this conformation rather than its being due to constraints imposed by disulfide bridges. When G is replaced with A, the peptide favors a helical conformation. This observation suggests that the positioning of cationic and hydrophobic residues in β-strands in HNP-1 is not the only structural feature that is essential for the exhibition of antibacterial activity.

We have observed that the activity of HNP-1 is not completely abolished in the presence of 100 mM NaCl, although there have been reports that the antibacterial activity of HNP-1 is completely lost in the presence of high salt concentrations (31, 44). It is conceivable that a loss in activity in the presence of NaCl may depend on the assay employed. A loss of antibacterial activity in the presence of a high salt concentration has been observed for HNP-1 in the radial diffusion assay, which has been extensively used to determine the antibacterial activities of mammalian defensins (44, 56). Also, the inhibition of antibacterial activity by human neutrophil defensins appears to be strain dependent (12, 44). Like HNP-1, all of the linear peptides permeabilize the outer membrane of E. coli. Subsequently, the linear peptides do not permeabilize the inner membrane to cause an influx of ONPG, as observed with HNP-1 (20, 21). However, it is likely that the site of action is the inner membrane, considering the rapid rate of killing. The linear analogs and HNP-1 are active even in the presence of CCCP. Since CCCP would discharge the pH gradient and destroy the proton motive force across the inner membrane, it appears that HNP-1 and the linear analogs can exert their antibacterial activity even in the absence of a proton motive force. It has been observed that the susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to the human defensin HNP-2 is not abolished in the presence of CCCP (40). The bactericidal activity of HNP-1 against S. aureus is also not dependent on the transcytoplasmic membrane electrical potential (52). Also, the loss of activity against P. aeruginosa in the presence of 100 mM NaCl is not observed when CCCP is present. The concentration of cytoplasmic Na+ is maintained by a Na+-proton antiporter driven by the proton motive force (10). CCCP inhibits the antiporter function (10, 33). In the presence of a high NaCl concentration in the external medium, the membrane potential does not favor associations of the peptides with the membrane of P. aeruginosa. However, when the membrane potential is dissipated by the addition of CCCP, the high salt concentration is no longer inhibitory. The linear peptides appear to exert their antibacterial activity in the same way as polymyxin B (8). As in the case of polymyxin B (8), the antibacterial activity of the linear peptides is inhibited by Mg2+. Tam and coworkers have engineered a salt-insensitive rabbit α-defensin with end-to-end cyclization (56). They have speculated that the clustering of cationic charges as a result of cyclization may promote salt insensitivity. In the absence of disulfide constraints, it is unlikely that a similar clustering of charges occurs in HNP-1ΔC. Hence, the linearization of defensin may be a good strategy to generate salt-insensitive antibacterial peptides.

The hemolytic assay indicates a reduction in hemolysis of human erythrocytes with the analog HNP-1ΔC18 and an increase with HNP-1ΔC18A. This may be due to decreased hydrophobicity in the case of HNP-1ΔC18 and a comparatively increased helicity as well as hydrophobicity for HNP-1ΔC18A, as observed for linear host defense antibacterial peptides (30, 37, 41). Earlier studies have shown that the microbicidal activity of HNPs is affected by the presence of serum (7, 55). We have also observed that serum inhibits the antibacterial activity of HNP-1. The HNP-1 analogs, particularly the truncated ones, show bactericidal activity even in the presence of human serum.

In summary, our studies have provided new insights into the structure-function relationship of HNP-1. While it has been demonstrated that all three disulfides or the order of connectivity is not an essential feature for activity in defensins (27, 29, 49), our results indicate that linear peptides without cysteines can still possess antibacterial activity, although it is 10- to 20-fold lower than that of HNP-1. The antibacterial activity is only marginally inhibited by high concentrations of NaCl, especially against E. coli and S. aureus. The peptides are active even in the absence of a proton motive force. The generation of linear defensins would be easier than that of disulfide-linked defensins, although defensins have been generated by chemical synthesis and recombination methods (6, 9, 17, 27-29, 36, 49-51, 56). Hence, linear defensins could have potential for development as therapeutic agents.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. V. Jagannadham, Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology, Hyderabad, India, for help with mass spectral analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atherton, E., and R. C. Sheppard. 1989. Solid phase peptide synthesis: a practical approach. IRL Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 2.Bals, R. 2000. Epithelial antimicrobial peptides in host defense against infection. Respir. Res. 1:141-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Befus, A. D., C. Mowat, M. Gilchrist, J. Hu, S. Solomon, and A. Bateman. 1999. Neutrophil defensins induce histamine secretion from mast cells: mechanisms of action. J. Immunol. 163:947-953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanco, F. J., and L. Serrano. 1995. Folding of protein G B1 domain studied by the conformational characterization of fragments comprising its secondary structure elements. Eur. J. Biochem. 230:634-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chertov, O., D. F. Michiel, L. Xu, J. M. Wang, K. Tani, W. J. Murphy, D. L. Longo, D. D. Taub, and J. J. Oppenheim. 1996. Identification of defensin-1, defensin-2, and CAP37/azurocidin as T-cell chemoattractant proteins released from interleukin-8-stimulated neutrophils. J. Biol. Chem. 271:2935-2940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Circo, R., B. Skerlavaj, R. Gennaro, A. Amoroso, and M. Zanetti. 2002. Structural and functional characterization of hBD-1(Ser35), a peptide deduced from a DEFB1 polymorphism. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 293:586-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daher, K. A., M. E. Selsted, and R. I. Lehrer. 1986. Direct inactivation of viruses by human granulocyte defensins. J. Virol. 60:1068-1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daugelavicius, R., E. Bakiene, and D. H. Bamford. 2000. Stages of polymyxin B interaction with the Escherichia coli cell envelope. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2969-2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawson, N. F., D. J. Craik, A. M. McManus, S. G. Dashper, E. C. Reynolds, G. W. Tregear, L. Otvos, Jr., and J. D. Wade. 2000. Chemical synthesis, characterization and activity of RK-1, a novel alpha-defensin-related peptide. J. Pept. Sci. 6:19-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dibrov, P. A. 1991. The role of sodium ion transport in Escherichia coli energetics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1056:209-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durr, M., and A. Peschel. 2002. Chemokines meet defensins: the emerging concepts of chemoattractants and antimicrobial peptides in host defense. Infect. Immun. 70:6515-6517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ericksen, B., Z. Wu, W. Lu, and R. I. Lehrer. 2005. Antibacterial activity and specificity of the six human α-defensins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:269-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganz, T. 2003. Defensins: antimicrobial peptides of innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:710-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gudmundsson, G. H., and B. Agerberth. 1999. Neutrophil antibacterial peptides, multifunctional effector molecules in the mammalian immune system. J. Immunol. Methods 232:45-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gullberg, U., N. Bengtsson, E. Bulow, D. Garwicz, A. Lindmark, and I. Olsson. 1999. Processing and targeting of granule proteins in human neutrophils. J. Immunol. Methods 232:201-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill, C. P., J. Yee, M. E. Selsted, and D. Eisenberg. 1991. Crystal structure of defensin HNP-3, an amphiphilic dimer: mechanisms of membrane permeabilization. Science 251:1481-1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoover, D. M., Z. Wu, K. Tucker, W. Lu, and J. Lubkowski. 2003. Antimicrobial characterization of human beta-defensin 3 derivatives. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2804-2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krishnakumari, V., A. Sharadadevi, S. Singh, and R. Nagaraj. 2003. Single disulfide and linear analogues corresponding to the carboxy-terminal segment of bovine beta-defensin-2: effects of introducing the beta-hairpin nucleating sequence d-Pro-Gly on antibacterial activity and biophysical properties. Biochemistry 42:9307-9315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehrer, R. I. 2004. Primate defensins. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:727-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehrer, R. I., A. Barton, K. A. Daher, S. S. Harwig, T. Ganz, and M. E. Selsted. 1989. Interaction of human defensins with Escherichia coli. Mechanism of bactericidal activity. J. Clin. Investig. 84:553-561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehrer, R. I., A. Barton, and T. Ganz. 1988. Concurrent assessment of inner and outer membrane permeabilization and bacteriolysis in E. coli by multiple-wavelength spectrophotometry. J. Immunol. Methods 108:153-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lehrer, R. I., and T. Ganz. 2002. Defensins of vertebrate animals. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14:96-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehrer, R. I., A. K. Lichtenstein, and T. Ganz. 1993. Defensins: antimicrobial and cytotoxic peptides of mammalian cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 11:105-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lillard, J. W., Jr., P. N. Boyaka, O. Chertov, J. J. Oppenheim, and J. R. McGhee. 1999. Mechanisms for induction of acquired host immunity by neutrophil peptide defensins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:651-656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loh, B., C. Grant, and R. E. Hancock. 1984. Use of the fluorescent probe 1-N-phenylnaphthylamine to study the interactions of aminoglycoside antibiotics with the outer membrane of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 26:546-551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowry, O. H., N. J. Rosebrough, A. L. Farr, and R. J. Randall. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265-275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maemoto, A., X. Qu, K. J. Rosengren, H. Tanabe, A. Henschen-Edman, D. J. Craik, and A. J. Ouellette. 2004. Functional analysis of the alpha-defensin disulfide array in mouse cryptdin-4. J. Biol. Chem. 279:44188-44196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mandal, M., and R. Nagaraj. 2002. Antibacterial activities and conformations of synthetic alpha-defensin HNP-1 and analogs with one, two and three disulfide bridges. J. Pept. Res. 59:95-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mandal, M., M. V. Jagannadham, and R. Nagaraj. 2002. Antibacterial activities and conformations of bovine beta-defensin BNBD-12 and analogs: structural and disulfide bridge requirements for activity. Peptides 23:413-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsuzaki, K. 1998. Magainins as paradigm for the mode of action of pore forming polypeptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1376:391-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagaoka, I., S. Hirota, S. Yomogida, A. Ohwada, and M. Hirata. 2000. Synergistic actions of antibacterial neutrophil defensins and cathelicidins. Inflamm. Res. 49:73-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niyonsaba, F., H. Ogawa, and I. Nagaoka. 2004. Human beta-defensin-2 functions as a chemotactic agent for tumour necrosis factor-alpha-treated human neutrophils. Immunology 111:273-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohyama, T., S. Mugikura, M. Nishikawa, K. Igarashi, and H. Kobayashi. 1992. Osmotic adaptation of Escherichia coli with a negligible proton motive force in the presence of carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone. J. Bacteriol. 174:2922-2928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pardi, A., X. L. Zhang, M. E. Selsted, J. J. Skalicky, and P. F. Yip. 1992. NMR studies of defensin antimicrobial peptides. 2. Three-dimensional structures of rabbit NP-2 and human HNP-1. Biochemistry 31:11357-11364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raj, P. A., and A. R. Dentino. 2002. Current status of defensins and their role in innate and adaptive immunity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 206:9-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rao, A. G., T. Rood, J. Maddox, and J. Duvick. 1992. Synthesis and characterization of defensin NP-1. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 40:507-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saberwal, G., and R. Nagaraj. 1994. Cell-lytic and antibacterial peptides that act by perturbing the barrier function of membranes: facets of their conformational features, structure-function correlations and membrane-perturbing abilities. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1197:109-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sedgwick, E. G., and P. D. Bragg. 1987. Distinct phases of the fluorescence response of the lipophilic probe N-phenyl-1-naphthylamine in intact cells and membrane vesicles of Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 894:499-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Selsted, M. E., and A. J. Ouellette. 1995. Defensins in granules of phagocytic and non-phagocytic cells. Trends Cell Biol. 5:114-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shafer, W. M., X. D. Qu, A. J. Waring, and R. I. Lehrer. 1998. Modulation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae susceptibility to vertebrate antibacterial peptides due to a member of the resistance/nodulation/division efflux pump family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:1829-1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sitaram, N., and R. Nagaraj. 1999. Interaction of antimicrobial peptides with biological and model membranes: structural and charge requirements for activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1462:29-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tam, J. P., C. R. Wu, W. Liu, and J. W. Zhang. 1991. Disulfide bond formation in peptides by dimethyl sulfoxide. Scope and applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113:6657-6662. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Territo, M. C., T. Ganz, M. E. Selsted, and R. Lehrer. 1989. Monocyte-chemotactic activity of defensins from human neutrophils. J. Clin. Investig. 84:2017-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turner, J., Y. Cho, N. N. Dinh, A. J. Waring, and R. I. Lehrer. 1998. Activities of LL-37, a cathelin-associated antimicrobial peptide of human neutrophils. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2206-2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vaara, M. 1992. Agents that increase the permeability of the outer membrane. Microbiol. Rev. 56:395-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Veber, D. F., J. D. Milkowski, S. L. Varga, R. G. Denkewalter, and R. Hirschmann. 1972. Acetamidomethyl. A novel thiol protecting group for cysteine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 94:5456-5461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vogel, H. J. 1953. Path of ornithine synthesis in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 39:578-583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Welling, M. M., P. S. Hiemstra, M. T. van den Barselaar, A. Paulusma-Annema, P. H. Nibbering, E. K. Pauwels, and W. Calame. 1998. Antibacterial activity of human neutrophil defensins in experimental infections in mice is accompanied by increased leukocyte accumulation. J. Clin. Investig. 102:1583-1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu, Z., D. M. Hoover, D. Yang, C. Boulegue, F. Santamaria, J. J. Oppenheim, J. Lubkowski, and W. Lu. 2003. Engineering disulfide bridges to dissect antimicrobial and chemotactic activities of human beta-defensin 3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:8880-8885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu, Z., B. Ericksen, K. Tucker, J. Lubkowski, and W. Lu. 2004. Synthesis and characterization of human alpha-defensins 4-6. J. Pept. Res. 64:118-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu, Z., A. Prahl, R. Powell, B. Ericksen, J. Lubkowski, and W. Lu. 2003. From pro defensins to defensins: synthesis and characterization of human neutrophil pro alpha-defensin-1 and its mature domain. J. Pept. Res. 62:53-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiong, Y. Q., M. R. Yeaman, and A. S. Bayer. 1999. In vitro antibacterial activities of platelet microbicidal protein and neutrophil defensin against Staphylococcus aureus are influenced by antibiotics differing in mechanism of action. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1111-1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang, D., A. Biragyn, L. W. Kwak, and J. J. Oppenheim. 2002. Mammalian defensins in immunity: more than just microbicidal. Trends Immunol. 23:291-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang, D., Q. Chen, O. Chertov, and J. J. Oppenheim. 2000. Human neutrophil defensins selectively chemoattract naive T and immature dendritic cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 68:9-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yasin, B., S. S. Harwig, R. I. Lehrer, and E. A. Wagar. 1996. Susceptibility of Chlamydia trachomatis to protegrins and defensins. Infect. Immun. 64:709-713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu, Q., R. I. Lehrer, and J. P. Tam. 2000. Engineered salt-insensitive alpha-defensins with end-to-end circularized structures. J. Biol. Chem. 275:3943-3949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang, X. L., M. E. Selsted, and A. Pardi. 1992. NMR studies of defensin antimicrobial peptides. 1. Resonance assignment and secondary structure determination of rabbit NP-2 and human HNP-1. Biochemistry 31:11348-11356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]