Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains that overexpress mexCD-oprJ become hypersusceptible to imipenem. Disruption of AmpC induction has been suggested to cause this phenotype. However, data from this study demonstrate that hypersusceptibility to imipenem can develop without changes in ampC expression or AmpC activity. Furthermore, hypersusceptibility is not caused by changes in expression of the outer membrane porin, OprD.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains that overexpress the MexCD-OprJ pump exhibit resistance to multiple antibiotics but become hypersusceptible to certain β-lactams and aminoglycosides (12). Hypersusceptibility to some β-lactams has been linked to a concurrent reduction in MexAB-OprM expression (3). However, imipenem is not extruded by MexAB-OprM (6); thus, another mechanism(s) must be involved. Masuda et al. suggested imipenem hypersusceptibility was due to a disruption in the induction pathway of AmpC cephalosporinase (13). However, imipenem is relatively stabile to AmpC hydrolysis, and large increases in AmpC activity alone do not significantly decrease imipenem susceptibility (2, 10, 11, 18, 23). Therefore, a disruption of ampC expression should not be solely responsible for imipenem hypersusceptibility among mexCD-oprJ-overexpressing P. aeruginosa.

An alternative mechanism may involve increased production of the outer membrane porin, OprD. A relationship between overexpression of the mexEF-oprN efflux system, decreased production of OprD, and imipenem resistance has been established (5, 15). Alternatively, mexCD-oprJ hyperexpression may elicit upregulation in oprD expression, thus promoting the entry of more carbapenem molecules and increased susceptibility to imipenem.

To test this hypothesis, mexCD-oprJ-overexpressing mutants were selected from four P. aeruginosa strains, and the relationship between AmpC, OprD, and imipenem hypersusceptibility was evaluated. An isogenic panel of P. aeruginosa isolates exhibiting various phenotypes for AmpC production served as the foundation for evaluating the role of AmpC. The parent, strain 164, was a “wild-type” clinical isolate that does not produce any β-lactamases other than its inherent chromosomal AmpC (17). A partially derepressed mutant, 164M1, and a fully derepressed mutant, 164CD, were previously selected from strain 164 through in vitro exposure to cephalosporins (2). OprD involvement was also investigated with an unrelated clinical isolate, P. aeruginosa 244, that was resistant to imipenem through the loss of OprD from its outer membrane.

Fluoroquinolone-resistant mutants were selected from the four P. aeruginosa strains using ciprofloxacin as the selecting agent (20), and changes in susceptibility to imipenem were evaluated by agar dilution (14). Two fluoroquinolone-resistant, imipenem-hypersusceptible (≥4-fold decrease in MIC) mutants were selected from each parent strain (Table 1). Overexpression of mexCD-oprJ was confirmed by real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) (described below), as a 700- to 1,500-fold increase in mexC expression was observed (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Phenotypes, susceptibilities, and gene expression of P. aeruginosa parents and mutantsa

| Strain | Phenotypeb | MIC (μg/ml)c

|

Expressiond

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIP | LEV | IMP | mexC | oprD | ||

| 164 | Wt | 0.25 | 1 | 4 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 164-921C | CDJ | 2 | 8 | 0.5 | 736 | 1.3 |

| 164-922C | CDJ | 2 | 8 | 0.5 | 799 | 1.1 |

| 164M1 | PD | 0.25 | 1 | 4 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 164M1-94C | CDJ | 2 | 8 | 1 | 1,332 | 0.75 |

| 164M1-84C | CDJ | 2 | 8 | 0.5 | 1,296 | 1.0 |

| 164CD | FD | 0.25 | 1 | 8 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 164CD-921C | CDJ | 2 | 8 | 2 | 1,304 | 0.76 |

| 164CD-822C | CDJ | 2 | 8 | 1 | 1,486 | 0.91 |

| 244 | ΔOprD | 0.125 | 0.5 | 16 | 1.0 | ND |

| 244-921C | CDJ | 2 | 4 | 2 | 926 | ND |

| 244-911C | CDJ | 2 | 4 | 2 | 687 | ND |

Parent strains and their phenotypes and data are shown in bold type.

Wt, phenotypic wild type for ampC expression; PD, partially derepressed for ampC expression; FD, fully derepressed for ampC expression; ΔOprD, OprD deficient; CDJ, overexpression of mexCD-oprJ.

Abbreviations: CIP, ciprofloxacin; LEV, levofloxacin; IMP, imipenem.

Transcriptional expression of mexC and oprD as measured by real-time RT-PCR. Values represent the difference (n-fold) in gene expression of the mutants relative to their respective parent strain. ND, not determined.

To investigate the contribution of AmpC to imipenem hypersusceptibility, cell-free lysates were prepared from untreated and imipenem-treated (1/4 the MIC) cultures, and AmpC hydrolysis was measured as previously described (16). For gene expression studies, total RNA was prepared using the TRIzolMax method (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Real-time RT-PCR was performed using 250 ng of DNase-treated RNA, the QIAGEN QuantiTect SYBR green RT-PCR kit (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, CA) and specific internal ampC primer pairs (0.5 μM in 50-μl final volume) (Table 2). The removal of contaminating DNA was verified by PCR in the absence of reverse transcriptase. Expression of the endogenous control gene, rpsL, was used to normalize data. Real-time RT-PCRs were carried out using an ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system, and results were analyzed with the ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system software. Relative quantification was determined by the 2−ΔΔCT or delta-delta cycle threshold (CT) method (9).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′→3′) | Product sizea | Accession no.b |

|---|---|---|---|

| MexCF1 | GCTGTTCCAGATCGATCCG | 160 | U57969 |

| MexCRTR | GGTATCGAAGTCCTGCTGG | ||

| PAERUGF | TTACTACAAGGTCGGCGACATGACC | 267 | X54719 |

| PAERUGR | GGCATTGGGATAGTTGCGGTTG | ||

| OprDRTF | CTACGCAATCACCGATAACC | 189 | Z14065 |

| PAOpDR2 | GTGGTGTTGCTGATGTCGC | ||

| RpsLF1 | GCAACTATCAACCAGCTGGTG | 230 | AE004842 |

| RpsLR1 | GCTGTGCTCTTGCAGGTTGTG |

Size of PCR products (bp).

Accession numbers for GenBank.

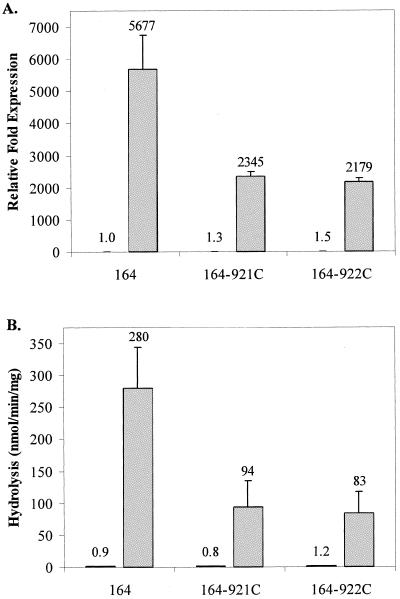

With untreated cultures of wild-type strain 164 and its imipenem-hypersusceptible mutants (164-921C and 164-922C), no differences were observed in ampC expression or AmpC hydrolysis (Fig. 1A and B). However, after imipenem treatment, ampC expression and hydrolysis activity were 2.4- to 3.4-fold lower for the imipenem-hypersusceptible mutants. These data support the earlier findings of Masuda et al. (13), but these modest decreases in ampC induction fail to explain hypersusceptibility, since far greater increases in AmpC activity do not significantly decrease imipenem susceptibility.

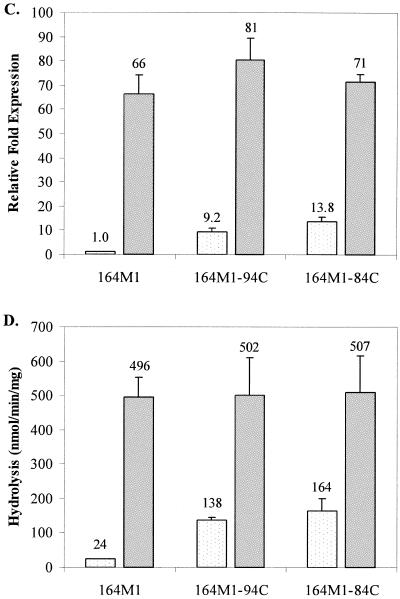

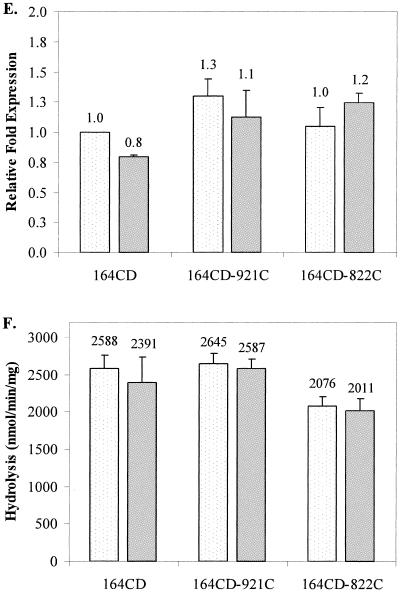

FIG. 1.

Transcriptional expression of ampC and AmpC β-lactamase activity in untreated and imipenem-treated cultures of parent strains 164 (A and B), 164M1 (C and D), and 164CD (E and F) and their respective imipenem-hypersusceptible mutants. Results from untreated cultures are displayed as lightly dotted bars, and results from imipenem-treated cultures are represented as solid gray bars. For ampC transcriptional expression studies (A, C, and E), values represent the amount of change in expression relative to untreated cultures of the parent strains (set at a value of 1.0). AmpC hydrolysis data (B, D, and F) reflect the actual nanomoles of cephalothin hydrolyzed per minute per mg of protein for cell extracts from each strain. The numbers above the bars represent the average values for two independent experiments, and error bars represent the standard deviations.

In contrast to P. aeruginosa 164 and its mutants, ampC expression and AmpC hydrolysis were significantly higher in untreated cultures of the imipenem-hypersusceptible mutants 164M1-94C and 164M1-84C from strain 164M1 than for imipenem-treated cultures (Fig. 1C and D). Following treatment with imipenem, these differences were no longer observed. In studies with fully derepressed strain 164CD and its imipenem-hypersusceptible mutants (164CD-921C and 164CD-822C), no differences were observed in ampC expression or AmpC hydrolysis activity, regardless of imipenem treatment (Fig. 1E and F). These data demonstrate that imipenem hypersusceptibility can develop without decreases in ampC expression or AmpC hydrolysis activity and suggest that the observations reported by Masuda et al. (13) relate only to “wild-type” P. aeruginosa. More importantly, the mechanism of imipenem hypersusceptibility does not appear to involve the AmpC cephalosporinase, as previously believed.

To evaluate the potential role of OprD, oprD transcription was examined by real-time RT-PCR (primers shown in Table 2). Steady-state levels of oprD expression were similar among all strains evaluated (Table 1), suggesting OprD is not involved in imipenem hypersusceptibility. These data do not rule out potential changes in posttranscriptional events. Therefore, imipenem-hypersusceptible mutants were selected from an OprD-deficient clinical isolate, P. aeruginosa 244. Sequence analysis (21) of oprD revealed a base transition from C→T at nucleotide 1438 (GenBank accession number Z14065), creating a premature translational stop codon (Gln235→stop). If OprD participated in hypersusceptibility to imipenem, this mutation would have to be restored to produce a functional porin in the outer membrane. Outer membrane protein analysis by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (22) demonstrated the continued absence of OprD among imipenem-hypersusceptible mutants 244-921C and 244-822C (data not shown).

If AmpC and OprD are not involved in the mechanism of imipenem hypersusceptibility, then other mechanisms must be operative. The P. aeruginosa genome contains several uncharacterized efflux pumps belonging to multiple families (19). If one of these uncharacterized pumps extrudes imipenem, one could hypothesize that overexpression of mexCD-oprJ may be associated with downregulation of the pump, similar to MexAB-OprM. Another potential mechanism includes changes in the overall composition of the outer membrane. Studies have shown that modifications in lipopolysaccharide can affect outer membrane integrity, dramatically decreasing resistance to toxic agents (1, 7). It is possible that the composition or architecture of the outer membrane of mexCD-oprJ-overexpressing mutants may be altered, rendering it more permeable to imipenem. A final alternative mechanism involves changes in the penicillin-binding protein (PBP) targets. Studies with both P. aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus have demonstrated that the overproduction of PBP3 and PBP4, respectively, can significantly decrease susceptibility to certain β-lactams (4, 8). In contrast, a decrease in the production of an imipenem-targeted PBP may lead to hypersusceptibility.

In summary, these data confirm that the mechanism of imipenem hypersusceptibility exhibited by mexCD-oprJ-overexpressing P. aeruginosa does not involve either AmpC or OprD. Understanding the mechanism of imipenem hypersusceptibility offers intriguing possibilities for discovering new drug targets capable of restoring susceptibility to carbapenems, even in strains lacking a functional OprD porin for their penetration.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angus, B. L., A. M. Carey, D. A. Caron, A. M. Kropinski, and R. E. Hancock. 1982. Outer membrane permeability in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: comparison of a wild-type with an antibiotic-supersusceptible mutant. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 21:299-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gates, M. L., C. C. Sanders, R. V. Goering, and W. E. Sanders, Jr. 1986. Evidence for multiple forms of type I chromosomal beta-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 30:453-457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gotoh, N., H. Tsujimoto, M. Tsuda, K. Okamoto, A. Nomura, T. Wada, M. Nakahashi, and T. Nishino. 1998. Characterization of the MexC-MexD-OprJ multidrug efflux system in ΔmexA-mexB-oprM mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1938-1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henze, U. U., and B. Berger-Bachi. 1996. Penicillin-binding protein 4 overproduction increases beta-lactam resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2121-2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kohler, T., S. F. Epp, L. K. Curty, and J. C. Pechere. 1999. Characterization of MexT, the regulator of the MexE-MexF-OprN multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 181:6300-6305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohler, T., M. Michea-Hamzehpour, S. F. Epp, and J. C. Pechere. 1999. Carbapenem activities against Pseudomonas aeruginosa: respective contributions of OprD and efflux systems. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:424-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kropinski, A. M., J. Kuzio, B. L. Angus, and R. E. Hancock. 1982. Chemical and chromatographic analysis of lipopolysaccharide from an antibiotic-supersusceptible mutant of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 21:310-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liao, X., and R. E. Hancock. 1997. Susceptibility to beta-lactam antibiotics of Pseudomonas aeruginosa overproducing penicillin-binding protein 3. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1158-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Livak, K. J., and T. D. Schmittgen. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔ CT method. Methods 25:402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Livermore, D. M. 1995. Beta-lactamases in laboratory and clinical resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:557-584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Livermore, D. M., and Y. J. Yang. 1987. Beta-lactamase lability and inducer power of newer beta-lactam antibiotics in relation to their activity against beta-lactamase-inducibility mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Infect. Dis. 155:775-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masuda, N., N. Gotoh, S. Ohya, and T. Nishino. 1996. Quantitative correlation between susceptibility and OprJ production in NfxB mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:909-913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masuda, N., E. Sakagawa, S. Ohya, N. Gotoh, and T. Nishino. 2001. Hypersusceptibility of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa nfxB mutant to beta-lactams due to reduced expression of the ampC beta-lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1284-1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1996. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 4th ed. Approved standard M7-A4. NCCLS, Wayne, Pa.

- 15.Ochs, M. M., M. P. McCusker, M. Bains, and R. E. Hancock. 1999. Negative regulation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane porin OprD selective for imipenem and basic amino acids. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1085-1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitout, J. D., E. S. Moland, C. C. Sanders, K. S. Thomson, and S. R. Fitzsimmons. 1997. Beta-lactamases and detection of beta-lactam resistance in Enterobacter spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:35-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Preheim, L. C., R. G. Penn, C. C. Sanders, R. V. Goering, and D. K. Giger. 1982. Emergence of resistance to beta-lactam and aminoglycoside antibiotics during moxalactam therapy of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 22:1037-1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanders, C. C., and W. E. Sanders, Jr. 1986. Type I beta-lactamases of gram-negative bacteria: interactions with beta-lactam antibiotics. J Infect. Dis. 154:792-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stover, C. K., X. Q. Pham, A. L. Erwin, S. D. Mizoguchi, P. Warrener, M. J. Hickey, F. S. Brinkman, W. O. Hufnagle, D. J. Kowalik, M. Lagrou, R. L. Garber, L. Goltry, E. Tolentino, S. Westbrock-Wadman, Y. Yuan, L. L. Brody, S. N. Coulter, K. R. Folger, A. Kas, K. Larbig, R. Lim, K. Smith, D. Spencer, G. K. Wong, Z. Wu, I. T. Paulsen, J. Reizer, M. H. Saier, R. E. Hancock, S. Lory, and M. V. Olson. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomson, K. S., C. C. Sanders, and M. E. Hayden. 1991. In vitro studies with five quinolones: evidence for changes in relative potency as quinolone resistance rises. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:2329-2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolter, D. J., N. D. Hanson, and P. D. Lister. 2004. Insertional inactivation of oprD in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa leading to carbapenem resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 236:137-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolter, D. J., E. Smith-Moland, R. V. Goering, N. D. Hanson, and P. D. Lister. 2004. Multidrug resistance associated with mexXY expression in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from a Texas hospital. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 50:43-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang, Y., N. Bhachech, and K. Bush. 1995. Biochemical comparison of imipenem, meropenem and biapenem: permeability, binding to penicillin-binding proteins, and stability to hydrolysis by beta-lactamases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 35:75-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]