Abstract

The enzyme l,d-carboxypeptidase A is involved in the recycling of bacterial peptidoglycan and is essential in Escherichia coli during stationary phase. By high-throughput screening, we have identified a dithiazoline inhibitor of the enzyme with a 50% inhibitory concentration of 3 μM. The inhibitor appeared to cause lysis of E. coli during stationary phase, behavior that is similar to a previously described deletion mutant of l,d-carboxypeptidase A (M. F. Templin, A. Ursinus, and J.-V. Holtje, EMBO J. 18:4108-4117, 1999). As much as a one-log drop in CFU in stationary phase was observed upon treatment of E. coli with the inhibitor, and the amount of intracellular tetrapeptide substrate increased by approximately 33%, consistent with inhibition of the enzyme within bacterial cells. Stationary-phase targets such as l,d-carboxypeptidase A are largely underrepresented as targets of the antibiotic armamentarium but provide potential opportunities to interfere with bacterial growth and persistence.

The peptidoglycan composing the bacterial cell wall undergoes extensive recycling. In Escherichia coli, approximately 50% of the cell wall is recycled with each generation (15). In the gram-negative recycling pathway, the pentapeptide l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-m-A2pm-d-Ala-d-Ala (where m-A2pm represents meso-diaminopimelic acid) is cleaved at the d-Ala-d-Ala bond by d,d-carboxypeptidases which include low-molecular-weight penicillin-binding proteins, releasing the terminal d-Ala (14, 18, 23, 24). In gram-positive bacteria, a similar reaction occurs, except for the substitution of l-Lys for m-A2pm. Enzymes known as l,d-carboxypeptidases then cleave at the m-A2pm-d-Ala bond in the tetrapeptide, again releasing d-Ala (reviewed in reference 19). The tripeptide l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-m-A2pm is a substrate for muropeptide ligase, which adds UDP-N-acetylmuramic acid (UDP-MurNAc) to the amino terminus (10). The UDP-MurNAc-tripeptide product of the muropeptide ligase reaction can then enter the de novo synthetic pathway as the substrate for MurF, which adds d-Ala-d-Ala to its carboxy terminus (4, 15, 22).

The existence of two types of l,d-carboxypeptidase activity in E. coli was established by Metz et al. (11, 12), with type I cleaving low-molecular-weight forms of the tetrapeptide, and type II cleaving tetrapeptide found in high-molecular-weight murein or cross-linked muropeptides. In an important advance, Templin et al. (20) cloned the ldcA gene and expressed the protein, which apparently encodes type I activity. These authors further established that ldcA is essential during stationary phase in E. coli, in that deletion of the gene causes lysis as the culture attains stationary phase. These data suggested that the LdcA enzyme could be appropriate as a novel target for an antibacterial agent specific for the stationary phase of bacterial growth. LdcA inhibitors would have potential antibacterial utility either alone or in combination with an agent that acts during the growing phase.

The protease mechanistic class of LdcA is unknown, and few inhibitors of LdcA have been identified. The LdcA inhibitors cephalosporin C, cefminox, and nocardicin A are β-lactams with a d-amino acid side chain and require relatively high concentrations (100 μg/ml, ∼100 μM) to achieve inhibition in vitro (20, 21). Nocardicin A binds to LdcA and can be used to purify the enzyme by affinity chromatography (21).

The standard method for the assay of LdcA activity has been high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) based, monitoring the production of tripeptide from tetrapeptide substrate isolated from bacteria (7, 21), making high-throughput screening for inhibitors of LdcA impractical. We have recently addressed these issues by implementing a fluorometric assay for the d-Ala cleavage product, using a synthetic peptide substrate (E. Z. Baum, submitted for publication). In the current communication, we report the identification of a dithiazoline inhibitor of LdcA using this assay in a high-throughput mode and characterized its behavior in causing lysis of E. coli cells in stationary phase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and purification of LdcA.

As the source of genomic DNA template, ten colonies of E. coli strain MG1655 (2) were scraped with a sterile inoculating loop into 50 μl of sterile water and boiled for 2 min. The open reading frame encoding LdcA (20), muramoyltetrapeptide carboxypeptidase (EC 3.4.1.7.13), was amplified using the PCR and primers LDC-up (5′ CGCTACTAACATATGTCTCTGTTTCACTTAATT 3′) and LDC-down (5′ CGCGGGATCCTTACATTTTAAGAACAGGATGACC 3′) (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., Coralville, IA). The primers contain NdeI and BamHI restriction sites, respectively (underlined); the ATG start and TAA stop codons are indicated (bold).

Reactions were assembled according to the protocol for Proof Start DNA Polymerase (QIAGEN, Inc., Valencia, CA). PCR was performed on the Perkin Elmer Cetus PCR System 9600, using 5 min hold at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 52°C, and 2 min at 72°C. The expected 0.9-kb PCR product was detected by agarose gel electrophoresis and was purified using the QIAGEN QIAquick PCR purification kit, cleaved with restriction enzymes NdeI and BamHI, repurified with QIAquick, and ligated into the NdeI and BamHI sites of pET14b (Novagen, Madison, WI), for expression with an amino-terminal hexahistidine tag under T7 promoter control. The ligation mixture was transformed into E. coli using Novablue Singles Competent Cells (Novagen). Plasmid from ampicillin-resistant cells was prepared using the QIAGEN plasmid midi kit and subjected to DNA sequence analysis (ACGT, Inc., Wheeling, IL). The cloned sequence was found to have the exact DNA sequence corresponding to E. coli locus NP415710 found in GenBank.

Plasmids (pLdcA) containing the ldcA gene were transformed into the E. coli expression strain BL21/pLysS. A 1-liter culture harboring plasmid pLdcA was grown to mid-log phase (A600 of 0.8), and LdcA protein expression was induced by addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 0.4 mM as recommended (Novagen). After 3 h of induction at 30°C, cells were pelleted by centrifugation (10 min at 10 × g), and the pellet was suspended in Bugbuster containing benzonase as recommended by the supplier (Novagen). The supernatant was applied to a Pharmacia HiPrep 26/10 desalting column (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The desalted sample in wash buffer (50 mM Tris/300 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) was applied to a Talon column (Clontech, BD Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA), and eluted in wash buffer containing 150 mM imidazole. The purified LdcA was dialyzed into 100 mM Tris, pH 8.5, containing 5% glycerol, frozen in aliquots at −70°C, and used in LdcA assays as described below. Typical yield was 40 mg of LdcA from a 1-liter culture.

LdcA assay.

The assay consisted of two parts: (i) cleavage of peptide substrate l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-l-Lys-d-Ala (or other peptides shown in Table 1) by LdcA enzyme, and (ii) detection of the d-Ala cleavage product using Amplex Red. The cleavage reaction was assembled in black half area 96 well flat bottom plates (Costar item 3694, Corning Life Sciences, Acton, MA). LdcA (30 μl of 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, containing 25 μg/ml of bovine serum albumin and 35 ng enzyme, 24 nM final concentration) was added to the wells, followed by 10 μl of 2 mM peptide (SynPep, Dublin, CA) in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, and the cleavage reaction was incubated for 30 min at 37°C, which is within the linear region of the reaction. If inhibitor was used, 2 μl was added and incubated with LdcA for 10 min at room temperature, prior to the addition of peptide.

TABLE 1.

Substrate specificity of LdcA for various synthetic peptides

| Peptide | Cleavagea (pmol/μl/min)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1×S, 1×E | 1×S, 10×E | 10×S, 1×E | 10×S, 10×E | |

| l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-l-Lys-d-Ala | 0.24b | >0.5c | ND | ND |

| d-Glu-l-Lys-d-Ala | <0.03 | 0.17b | <0.03 | 0.33b |

| l-Lys-d-Ala | <0.03 | <0.03 | <0.03 | <0.03 |

| l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-l-Lys-l-Ala | <0.03 | <0.03 | <0.03 | <0.03 |

| l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-A2pm-d-Alad | 0.12b | ND | ND | ND |

pmol d-Ala (or l-Ala in the case of l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-l-Lys-l-Ala) generated/μl/min. Standard conditions were 500 μM peptide substrate (1×S) and 24 nM LdcA (1×E). Tenfold higher concentrations of substrate (10×S) or LdcA (10×E) were used as shown. ND, not determined.

Coefficient of variation for these numbers was 1.3 to 7.6%.

d-Ala reading was beyond the linear range of the fluorometer.

A2pm is a mixture of meso, dd, and ll isomers.

The detection reaction consisted of 40 μl of 100 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.5, containing 12.5 units/ml horseradish peroxidase, 0.38 units/ml d-amino acid oxidase, 6.25 μg/ml flavin adenine dinucleotide, and 50 μM Amplex Red (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) (5) and was added to the completed cleavage reaction. After incubation for 30 min at 37°C, the plate was read on a SpectraMax Gemini XS Fluorometer (Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA; excitation 530 nm, emission 590 nm). In the case of peptide l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-l-Lys-l-Ala, d-amino acid oxidase was replaced by l-amino acid oxidase from Crotalus adamanteus at 1.9 units/ml, and the detection reaction was incubated for 60 min.

Microbiology studies.

MIC assays were performed by the broth microdilution method (13), using the following bacterial strains: E. coli strains MG1655, ATCC 25922, CP9 (16, 17), OC9040, and lipopolysaccharide-deficient OC2530; Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains PA103 and ATCC 27853; and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213.

For bacterial growth curves, the Bioscreen C Microbiology Reader was utilized with Growth Curves v2.28 software (Oy Growth Curves AB Ltd., Helsinki, Finland). For most growth experiments, an overnight culture of E. coli strain MG1655 was diluted 1:50 in Miller's LB broth, and 100 μl of the freshly diluted cells was added to replicate wells of a Bioscreen 100-well plate. The plate was incubated in the Bioscreen at 37°C with continuous shaking, with an absorbance reading taken every 30 min using the 420- to 580 -nm filter. The dithiazoline compound (DTZ, Fig. 1) (in 5 μl 30% dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) or DMSO control was added at the indicated times. For colony counts, a Whitley Automatic Spiral Plater and a Synbiosis ProtoCOL Colony Counter (Microbiology International, Frederick, MD) were used as per the manufacturers' instructions, on a dilution in phosphate-buffered saline of 10−5 from an aliquot of cells removed from replicate wells of the Bioscreen.

FIG. 1.

Structure of the DTZ inhibitor of LdcA.

To examine the effect of LdcA protein levels on E. coli growth curves (Fig. 4), strain BL21/pLysS harboring either pLdcA, or control plasmid expressing MurF (pMurF), were grown in a tube of LB containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (34 μg/ml). At an A600 of 0.4, aliquots of cells were transferred to the wells of a Bioscreen plate containing the indicated levels of IPTG and DTZ, and growth was monitored as described above. At 3 h, samples were taken for gel electrophoresis to display the amount of recombinant LdcA or MurF protein made in response to IPTG induction.

FIG. 4.

Effect of LdcA overexpression on E. coli growth curves. (A) Protein expression in response to IPTG. E. coli BL21/pLysS cells harboring either pLdcA (lanes 1 to 4) or pMurF (lanes 5 to 8) were treated with IPTG for 3 h prior to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis as follows: no IPTG, lanes 1 and 5; 6 μM IPTG, lanes 2 and 6; 25 μM IPTG, lanes 3 and 7; 100 μM IPTG, lanes 4 and 8. The arrows at left and right indicate the LdcA and MurF proteins, respectively. Growth of bacterial cells harboring (B) pLdcA or (C) pMurF was monitored on the Bioscreen. Cells without IPTG and without DTZ treatment, solid circles. Similar curves were obtained for IPTG-containing samples lacking DTZ. Cells treated with DTZ (50 μM) and either no IPTG (squares), 6 μM IPTG (triangles), or 25 μM IPTG (open circles). A representative growth curve for each condition, from duplicate curves generated in two independent experiments, is shown.

Bacterial membrane damage assay.

The BacLight LIVE/DEAD kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was used to assess membrane damage. An overnight culture of E. coli MG1655 in CAMHB was diluted 1:100 in fresh CAMHB and allowed to regrow at 37°C with shaking (200 rpm) for 3.5 h (mid-log, A600 of 0.5) or 15 h (stationary phase). The stationary culture was then adjusted to 0.5 A600, and both cultures were processed for BacLight studies as described previously (6), incubating with DTZ (100 μM final concentration) or DMSO for 10 min.

Quantitation of tetrapeptide in E. coli.

Strain MG1655 was grown to A600 of 0.4, and 10 ml of culture was treated with either 50 μM DTZ in DMSO or DMSO alone, with continued incubation for 3 h or 8 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation, washed with saline, and suspended in 100 μl H2O. Soluble murein precursors were extracted by boiling as described (20), and tetrapeptide l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-m-A2pm-d-Ala was quantitated by HPLC-mass spectrometry (MS) by comparison to synthetic tetrapeptide standard, using a Waters HPLC system coupled with a Waters Quattro Premier triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Milford, MA). Peptide samples were separated on a Waters Atlantis dC18 column by a 5-min step gradient using an aqueous acetonitrile mobile phase. All analytes were ionized in the electrospray ionization interface and detected under the optimized MS conditions. The full scan mass spectra were acquired from m/z 100 up to 1300. The tetrapeptide was detected at m/z 462.

RESULTS

Substrate specificity of LdcA.

Previous studies on the substrate specificity of LdcA have relied on substrates purified from bacteria (8, 9, 20). Templin et al. (20) isolated UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide, processed it in vitro to produce the various forms of tetrapeptide substrate, and demonstrated that the presence of UDP-MurNAc or MurNAc at the amino terminus of peptide l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-m-A2pm-d-Ala was not required for cleavage by LdcA to occur. These data suggested to us that synthetic peptides lacking any amino-terminal modification would be suitable for analysis of the substrate specificity of LdcA. It was not possible to obtain pure m-A2pm-containing peptide since the A2pm used for commercial peptide synthesis is a mixture of meso-, dd, and ll isomers in an unknown ratio, but likely to be 2:1:1. As seen in Table 1, recombinant E. coli LdcA cleaved l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-l-Lys-d-Ala, which would correspond to gram-positive substrate, approximately twofold faster than the diastereomeric mixture l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-A2pm-d-Ala, the gram-negative substrate normally found in E. coli (except containing only meso-A2pm). Our preference was to use the readily available and relatively inexpensive substrate l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-l-Lys-d-Ala for high-throughput screening since it appeared to be cleaved with comparable efficiency. Substitution of the terminal d-Ala with an l-Ala residue prevented cleavage, reinforcing the view that LdcA is truly an l,d-carboxypeptidase (Table 1).

The length requirement of the substrate was also examined, by synthesis of peptides truncated from the amino terminus. Using the standard conditions of peptide concentration (500 μM), similar to conditions used previously (8, 20, 21), and enzyme concentration (24 nM), neither the tripeptide d-Glu-l-Lys-d-Ala nor the dipeptide l-Lys-d-Ala served as a substrate. In the case of the tripeptide, increasing the concentration of enzyme by 10-fold did result in cleavage of substrate, at a rate of 0.17 pmol d-Ala/μl/min relative to cleavage of the tetrapeptide control of 0.24 (at 10-fold less enzyme) (Table 1). Separately increasing the tripeptide concentration by 10-fold did not cause cleavage to occur, suggesting that lack of cleavage of the tripeptide under standard conditions is not solely due to a low affinity (high Km) of LdcA for this substrate.

The observation that increasing LdcA concentration resulted in cleavage may suggest that the tripeptide is inhibitory to the cleavage reaction. In support of this, tripeptide (1 mM) inhibited cleavage of tetrapeptide by approximately 33% (data not shown). However, increasing both the tripeptide and LdcA concentration 10-fold did further enhance cleavage twofold relative to increasing only LdcA (Table 1, 0.33 versus 0.17), suggesting that a high Km, slow kcat, and an inhibitory property of the tripeptide could contribute to lack of cleavage under standard conditions. The dipeptide (at 1 mM) was not inhibitory to tetrapeptide cleavage (data not shown).

Identification of a dithiazoline inhibitor of LdcA.

A newly developed high-throughput assay for the identification of inhibitors of LdcA was used to screen a chemical library, and a series of dithiazolines were identified as inhibitors of the enzyme. A representative compound, designated DTZ, is shown (Fig. 1). This compound displayed an IC50 value of 3 μM in the LdcA assay. The inhibitory activity of DTZ was also tested against other enzymes. The LdcA assay relies on the detection of d-Ala product using the coupled enzymes horseradish peroxidase and d-amino acid oxidase; DTZ (at 10 μM) did not inhibit either enzyme of the detection system. The compound (at 25 μM) was not inhibitory to the serine β-lactamases TEM-1 and P99, the Zn metalloprotease ADAM8, and several other proteases (cathepsin C, E, G, S, and Z, chymase, and tryptase). DTZ was also inactive against the E. coli cell wall synthesis enzyme MurA, an E. coli S-30 transcription-translation extract, and numerous other enzymes, including alkaline phosphatase and E. coli ligase.

DTZ was tested for antibacterial activity using a panel of organisms which included E. coli, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa strains and displayed MICs of >64 μg/ml in each case. Since the antibacterial assay monitors the appearance of visible bacteria in an overnight assay following completion of exponential growth, and an LdcA inhibitor is expected to act during stationary phase, it is likely that a true LdcA inhibitor would lack antibacterial activity in this assay, unless large-scale lysis of stationary-phase cells were to occur. Thus, lack of a measurable MIC in this assay does not exclude inhibition of LdcA as a possible mechanism of action of DTZ in bacteria, and may in fact be consistent with such a mechanism.

To further address whether DTZ was capable of LdcA inhibition in E. coli, time courses of cell growth were examined. Control E. coli MG1655 cultures, to which the DMSO vehicle was added, displayed a characteristic period of exponential growth, reaching maximal optical density (OD) at about 8 h, followed by a slow, slight decline in OD under these experimental conditions (Fig. 2A). In contrast, E. coli cultures containing DTZ displayed a marked and reproducible decrease in OD upon attainment of stationary phase at 8 h. Similar behavior was observed for a variety of other E. coli strains, including wild type CP9 and OC9040, and lipopolysaccharide-deficient OC2530 (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

A. Effect of the LdcA inhibitor DTZ on the growth of E. coli MG1655 cultures. An overnight culture was diluted 1,000-fold with fresh medium and incubated at 37°C with shaking for 2 h. Cells (100 μl) were then added to duplicate Bioscreen wells containing 5 μl of DMSO or DTZ at a final concentration of 50 μM and incubated on the Bioscreen for 24 h. The arrows indicate the time of removal of samples from additional replicate wells for determination of CFU. B. CFU from control and DTZ-treated samples at 8 h (open bars) and at 11 h (gray bars).

To determine whether this decline in OD corresponded to cell lysis, aliquots of these cultures were taken at 8 h and at 11 h, corresponding to the maximal and minimal OD after attainment of stationary phase (Fig. 2A, arrows), and CFU were determined (Fig. 2B). The bacterial counts of the control samples were essentially constant between 8 and 11 h, at 3 × 109 CFU/ml. In contrast, for the samples containing DTZ, a decline in bacterial counts of approximately sixfold was observed at 11 h compared to 8 h. The decline in both OD and CFU suggests that lysis occurred in the DTZ-treated samples. The small amount of lysis of control cells (with or without DMSO treatment) after prolonged growth in stationary phase as suggested by the slight decline in both OD and in CFU (<20%) seen in Fig. 2 is reproducible.

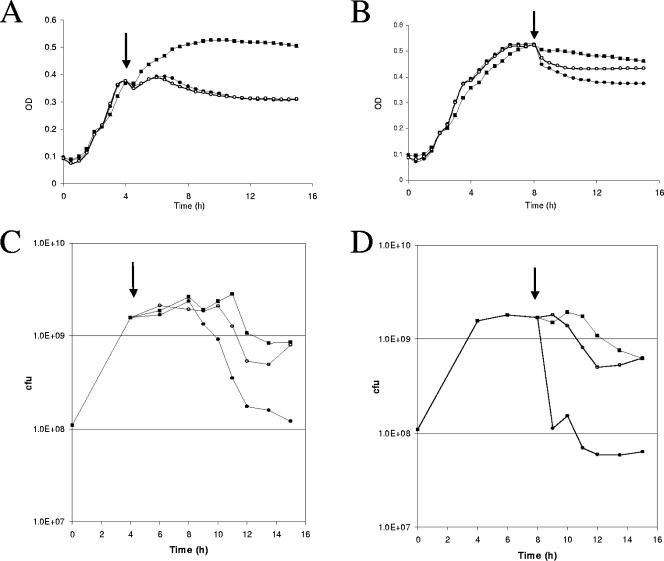

The preceding experiment involved addition of DTZ very early in the growth phase, prior to the onset of rapid exponential growth. The effect of delayed addition of compound was also examined, at 4 h and 8 h, corresponding to mid-logarithmic and stationary phases, respectively (Fig. 3). Delayed addition of DTZ was effective at causing both the decline in OD (Fig. 3A and B) and the decline in CFU (Fig. 3C and D). In contrast to the OD profile for early addition of compound (time zero, Fig. 2A) of essentially normal growth for several hours until stationary phase is attained, DTZ addition has a more rapid effect when added at either 4 h or 8 h. For addition at 4 h (Fig. 3A, 200 μM), an arrest in OD occurred within 30 min, and the OD profile showed a decline starting at about 8 h. The bacterial count also stayed constant until about 8 h (Fig. 3C). As the OD declined, bacterial counts gradually declined, by about 10-fold relative to the control by 16 h.

FIG. 3.

Effect of delayed addition of DTZ inhibitor on E. coli MG1655 growth curves (A and B) and CFU (C and D). DTZ (open circles, 50 μM; solid circles, 200 μM) or DMSO (squares) was added to wells of the Bioscreen at 4 h (panel A) or 8 h (panel B). A representative of 10 replicate wells is shown. At the indicated times, aliquots were removed from wells to which had compound added at 4 h (panel C) or at 8 h (panel D), for CFU determination. Arrows indicate time of addition of DTZ or DMSO.

In the case of addition of DTZ at 8 h (Fig. 3B, 200 μM), the decline in OD began rapidly, within 30 min after compound addition. The decline in OD again correlated well with the observed drop in CFU (Fig. 3D). For DTZ addition at 8 h, bacterial counts dropped by about 16-fold relative to the control by the 9-h time point and remained about 10-fold lower than the control through the 16-h time point

Thus, from these experiments, it appeared that DTZ caused lysis of cells as the culture reached the onset of stationary phase. DTZ does not appear to be a general membrane-damaging agent, as demonstrated by its lack of activity (at 100 μM) against both log- and stationary-phase cultures of E. coli MG1655 in the BacLight assay. DTZ was also inactive at 100 μM in an equine erythrocyte hemolysis assay (6). This DTZ-mediated lysis is similar to the behavior of the E. coli deletion mutant of ldcA; a decline in OD was also observed, accompanied by a 50-fold drop in CFU at stationary phase (20). Those authors demonstrated an increase in the amount of tetrapeptide in the deletion mutant compared to the wild-type strain.

To address whether DTZ treatment also causes tetrapeptide to accumulate, as would be expected if LdcA were inhibited, the amount of tetrapeptide in control and DTZ-treated cells was determined by HPLC-MS (Table 2). Treatment with DTZ resulted in a reproducible increase in the amount of tetrapeptide relative to the control sample of 33 ± 4% in stationary phase (8 h). This result is consistent with inhibition of LdcA within bacterial cells as the cause of the observed cell lysis. If tetrapeptide was instead quantitated from DTZ-treated cells in log phase (at 3 h), prior to lysis, the amount of tetrapeptide was similar in DTZ-treated and control samples. Thus, accumulation of tetrapeptide, like lysis, appears to occur during stationary phase.

TABLE 2.

Quantitation of tetrapeptide in DTZ-treated cells relative to the controla

| Expt | % Increase in tetrapeptide after DTZ exposure for:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 3 h | 8 h | |

| 1 | NDb | 29 |

| 2 | 4 | 37 |

| Avg | 33 ± 4 | |

Extracts were prepared from E. coli MG1655 with or without DTZ (50 μM) treatment as described in the text. Tetrapeptide was quantitated by HPLC-MS. The amount of tetrapeptide in control samples is defined as 100%; the increase in tetrapeptide relative to the control sample is shown. In experiment 1, cells were taken directly from the wells of a Bioscreen plate; in experiment 2, cells were grown in a flask.

ND, not determined.

Consequence of elevated LdcA levels on the DTZ effect in E. coli.

To support the idea that LdcA was actually the target of DTZ within bacterial cells, the effect of increasing the level of LdcA protein within E. coli was examined. E. coli strain BL21/pLysS harboring a plasmid encoding either LdcA or the control protein MurF was induced with various levels of IPTG. The amount of recombinant LdcA and MurF produced showed an IPTG-dependent dose-response (Fig. 4A). In the absence of IPTG, E. coli harboring pLdcA demonstrated the characteristic decline in OD as stationary phase was attained. The presence of IPTG, and the resultant increase in LdcA protein levels, partially prevented the DTZ-mediated decline in OD (Fig. 4B). These data are consistent with LdcA's being the target of DTZ within bacterial cells. The control E. coli strain harboring pMurF exhibited a decline in OD at the onset of stationary phase, which was not prevented by the presence of IPTG (Fig. 4C).

Effect of DTZ on other Enterobacteriaceae.

To determine whether DTZ had an effect on the growth of other Enterobacteriaceae, a homology search was first performed, using the amino acid sequence of LdcA. The LdcA homolog Q8ZP18 found in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is 80% identical (and 87% similar if conservative amino acid changes are included) to the E. coli sequence. A growth curve study was performed using S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain ATCC 14028, in the presence and absence of DTZ (Fig. 5). The effect of DTZ on the OD of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium cultures (Fig. 5A) was similar to the effect seen in E. coli (Fig. 5B) of normal growth until stationary phase was attained, at which point a decline in OD was reproducibly observed. These data suggest that the effect of DTZ is not limited to E. coli and that DTZ may be able to inhibit LdcA homologs in other bacterial species.

FIG. 5.

Growth of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium in the presence of DTZ. Colonies of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain ATCC 14028 (A) or E. coli strain MG1655 (B) were inoculated into a tube of LB and grown with shaking for 2 h at 37°C. Aliquots (100 μl) of cells were then added to wells of a Bioscreen plate containing either DMSO (squares) or DTZ at a final concentration of 50 μM (open circles) or 150 μM (solid circles). The OD was monitored for an additional 16 h.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have demonstrated for the first time that synthetic tetrapeptides are useful as substrates for the study of LdcA, eliminating the need to purify and process substrate from bacteria. Of particular interest is the finding that l-Lys-containing tetrapeptide appears to be utilized with comparable efficiency as A2pm-containing tetrapeptide. This is important because l-Lys-containing synthetic peptide has the advantage of being a single isomer, whereas A2pm for peptide synthesis is a mixture of dd, ll, and meso isoforms. Synthetic peptide containing l-Lys is also more widely available from commercial sources and is considerably less expensive than the corresponding A2pm-containing peptide.

The observation that half of the amount of d-Ala product was made from the enantiomerically impure A2pm tetrapeptide compared to the l-Lys-containing peptide, may indicate that only the m-A2pm-containing tetrapeptide, and not the dd- or ll-A2pm-containing tetrapeptide, was utilized as a substrate by LdcA. Since Lys lacks a second carboxylate group compared to A2pm, but is otherwise similar, it was not unexpected that tetrapeptide containing the smaller l-Lys moiety could be utilized by the LdcA enzyme. Analogous results have been found for E. coli MurF using substrates purified from gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, in that Lys-containing tripeptide was utilized as efficiently as the substrate containing m-A2pm (1). It is possible that other enzymes in the gram-negative cell wall biosynthesis and recycling pathways may also accept substitution of l-Lys for m-A2pm, which is an advantage if synthetic peptides are desirable, both for isomeric purity, availability, and cost.

Previous studies using biosynthetically modified peptides either in intact E. coli cells (9) or purified from bacteria for use in LdcA studies in vitro (8) had shown that there is some flexibility in this third position of the peptide, in that lanthionine or cystathionine was tolerated but not l-ornithine. Although our results demonstrating the successful utilization of the l-Lys-containing tetrapeptide by LdcA are in contrast with a previous study by Metz et al. (12), which demonstrated that Lys-containing tetrapeptide was not a substrate for their purified E. coli l,d-carboxypeptidase “activity I,” their enzyme, of 12 kDa, cannot be the same as the 32-kDa enzyme described by Templin et al. (20) and used in the current study.

All of the previously identified inhibitors of LdcA were β-lactams with a d-amino acid side chain (20, 21). The DTZ inhibitor of LdcA identified in this study and a benzoxazine derivative (E. Z. Baum, submitted for publication) are the first non-β-lactam inhibitors of the enzyme to be described. DTZ displayed a significantly lower IC50 value (3 μM) in the enzyme assay than the β-lactams cephalosporin C, cefminox, and nocardicin A, approximately 100 μM (20, 21). The activity of these β-lactams against LdcA within bacterial cells may be difficult to assess because their well-known activity against penicillin-binding proteins is likely to be the major mechanism of antibacterial action.

DTZ appeared to act on the LdcA target within bacterial cells, as suggested by the decline in both OD and in CFU at the onset of stationary phase. These data are consistent with DTZ-mediated lysis via inhibition of LdcA, although it is possible that another mechanism was involved in cell death. Also, increasing the amount of LdcA protein within bacterial cells partially prevented the decline in OD. Additional evidence for LdcA inhibition is provided by the accumulation of tetrapeptide substrate in DTZ-treated cells relative to untreated control cells.

Both stationary-phase lysis and accumulation of tetrapeptide were observed in an ldcA deletion mutant (20). In the case of the deletion mutant, a 50-fold drop in bacterial counts was observed and may represent the maximum amount of lysis that complete inhibition of LdcA could provide. Thus, the 10-fold drop in bacterial counts observed upon DTZ treatment may suggest that only partial inhibition of LdcA in bacteria was achieved. It is difficult to compare the 33% increase in the tetrapeptide level seen upon DTZ treatment with the change in tetrapeptide level in the deletion mutant since those authors used radiolabeled A2pm to track tetrapeptide, and under their experimental conditions, incorporation levels were low.

Lysis is thought to be a consequence of accumulation of toxic UDP-MurNAc-tetrapeptide, a dead-end intermediate (20). UDP-MurNAc-tetrapeptide is formed by the activity of muropeptide ligase, which adds UDP-MurNAc to the tetrapeptide that accumulates in the absence of LdcA activity. UDP-MurNAc-tetrapeptide is incorporated into the murein sacculus, interfering with polymer cross-linking and weakening the cell wall, resulting in lysis (20).

Importantly, DTZ did not appear to have antibacterial activity in standard broth microdilution assays (MIC > 64 μg/ml), which may actually support the proposal that it acts during the stationary phase of growth, since a drop of only 10-fold in the number of cells may not be sufficient to register as active in this assay. This raises the general question of how to develop structure-activity relationships for antibacterial compounds that act during stationary phase and may not exhibit MICs. Coates et al. (3) have introduced the concept of minimum stationary-cidal concentration to address this issue for cidal compounds. In the case of LdcA inhibitors, as shown in the current communication, it is likely that the decrease in CFU could be monitored. An assay for other stationary-phase targets whose inhibition does not result in lysis could be further complicated by inhibitors which are static rather than cidal, which would necessitate plating for viable bacteria in the continued presence of the inhibitor.

The discovery of new antibacterial agents with new mechanisms of action is critical to combat the well-known problem of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The majority of known antibiotics act only against growing cells, and few are effective against stationary-phase cells (3). Many infections contain both growing and nongrowing cells, including biofilms, bacterial pneumonia, and tuberculosis (3). Stationary-phase targets may represent a relatively underexplored area of antibiotic research. It remains to be determined whether an agent such as an LdcA inhibitor, which in theory may provide only a 50-fold drop in bacterial counts based on a deletion mutant (20), would be potent enough to have clinical utility. It is possible that combination therapy of infections with agents that target both growing cells and stationary-phase cells may be required for optimization of these new agents.

Acknowledgments

We thank Linh Ly for cloning the ldcA gene and Ellyn Wira and Deepika Raina for assistance with microbiology experiments. We thank Anne Marie Queenan for β-lactamase data, Anne Fourie for metalloprotease experiments, and Chip Fleming for high-throughput screening. Mark Macielag provided expert chemical advice and helpful comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, M. S., S. S. Eveland, H. R. Onishi, and D. L. Pompliano. 1996. Kinetic mechanism of the Escherichia coli UDPMurNAc-tripeptide d-alanyl-d-alanine-adding enzyme: use of a glutathione S-transferase fusion. Biochemistry 35:16264-16269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett 3rd, C. A. Bloch, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado-Vides, J. D. Glasner, C. K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, N. W. Davis, H. A. Kirkpatrick, M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and Y. Shao. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coates, A., Y. Hu, R. Bax, and C. Page. 2002. The future challenges facing the development of new antimicrobial drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Disc. 1:895-910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodell, E. W. 1985. Recycling of murein by Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 163:305-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gutheil, W. G., M. E. Stefanova, and R. A. Nicholas. 2000. Fluorescent coupled enzyme assays for d-alanine: application to penicillin-binding protein and vancomycin activity assays. Anal. Biochem. 287:196-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilliard, J. J., R. M. Goldschmidt, L. Licata, E. Z. Baum, and K. Bush. 1999. Multiple mechanisms of action for inhibitors of histidine protein kinases from bacterial two-component systems. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1693-1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohlrausch, U., and J. V. Hoeltje. 1991. One-step purification procedure for UDP-N-acetylmuramyl-peptide murein precursors from Bacillus cereus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 78:253-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leguina, J. I., J. C. Quintela, and M. A. de Pedro. 1994. Substrate specificity of Escherichia coli Ld-carboxypeptidase on biosynthetically modified muropeptides. FEBS Lett. 339:249-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mengin-Lecreulx, D., D. Blanot, and J. van Heijenoort. 1994. Replacement of diaminopimelic acid by cystathionine or lanthionine in the peptidoglycan of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 176:4321-4327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mengin-Lecreulx, D., J. van Heijenoort, and J. T. Park. 1996. Identification of the mpl gene encoding UDP-N-acetylmuramate: l-alanyl-γ-d-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelate ligase in Escherichia coli and its role in recycling of cell wall peptidoglycan. J. Bacteriol. 178:5347-5352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Metz, R., S. Henning, and W. P. Hammes. 1986. ld-carboxypeptidase activity in Escherichia coli. I. The ld-carboxypeptidase activity in ether treated cells. Arch. Microbiol. 144:175-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metz, R., S. Henning, and W. P. Hammes. 1986. ld-carboxypeptidase activity in Escherichia coli. II. Isolation, purification and characterization of the enzyme from E. coli K 12. Arch. Microbiol. 144:181-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2003. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 5th ed. Approved standard M7-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 14.Nelson, D. E., A. S. Ghosh, A. L. Paulson, and K. D. Young. 2002. Contribution of membrane-binding and enzymatic domains of penicillin binding protein 5 to maintenance of uniform cellular morphology of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:3630-3639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park, J. T. 1995. Why does Escherichia coli recycle its cell wall peptides? Mol. Microbiol. 17:421-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russo, T. A., Y. Liang, and A. S. Cross. 1994. The presence of K54 capsular polysaccharide increases the pathogenicity of Escherichia coli in vivo. J. Infect. Dis. 169:112-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russo, T. A., G. Sharma, J. Weiss, and C. Brown. 1995. The construction and characterization of colanic acid deficient mutants in an extraintestinal isolate of Escherichia coli (O4/K54/H5). Microb. Pathog. 18:269-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Templin, M. F., and J.-V. Hoeltje. 2004. Murein dd-endopeptidase PBP-7, p. 1953-1956. In A. J. Barrett, N. D. Rawlings, and J. F. Woessner (ed.), Handbook of proteolytic enzymes, 2nd ed. Elsevier Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 19.Templin, M. F., and J.-V. Hoeltje. 2004. Murein tetrapeptide ld-carboxypeptidases, p. 2118-2120. In A. J. Barrett, N. D. Rawlings, and J. F. Woessner (ed.), Handbook of proteolytic enzymes, 2nd ed. Elsevier Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 20.Templin, M. F., A. Ursinus, and J.-V. Holtje. 1999. A defect in cell wall recycling triggers autolysis during the stationary growth phase of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 18:4108-4117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ursinus, A., H. Steinhaus, and J. V. Hoeltje. 1992. Purification of a nocardicin A-sensitive l,d-carboxypeptidase from Escherichia coli by affinity chromatography. J. Bacteriol. 174:441-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Heijenoort, J. 2001. Recent advances in the formation of the bacterial peptidoglycan monomer unit. Nat. Prod. Rep. 18:503-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkin, J.-M., and M. Nguyen-Disteche. 2004. Penicillin-binding protein 5, a serine-type d-Ala-d-Ala carboxypeptidase, p. 1950-1953. In A. J. Barrett, N. D. Rawlings, and J. F. Woessner (ed.), Handbook of proteolytic enzymes, 2nd ed. Elsevier Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 24.Woessner, J. F. 2004. Muramoyl pentapeptide carboxypeptidase, p. 1970-1971. In A. J. Barrett, N. D. Rawlings, and J. F. Woessner (ed.), Handbook of proteolytic enzymes, 2nd ed. Elsevier Academic Press, New York, N.Y.