Abstract

We characterized 100 Escherichia coli urosepsis isolates from adult patients according to host compromise status by means of ribotyping, PCR phylogenetic grouping, and PCR detection of papG alleles and the virulence-related genes sfa/foc, fyuA, irp-2, aer, hly, cnf-1 and hra. We also tested these strains for copies of pap and hly and their direct physical linkage with other virulence genes in an attempt to look for pathogenicity islands (PAIs) described for the archetypal uropathogenic strains J96, CFT073, and 536. Most of the isolates belonged to E. coli phylogenetic groups B2 and D and bore papG allele II, aer, and fyuA/irp-2. papG allele II-bearing strains were more common in noncompromised patients, while papG allele-negative strains were significantly more frequent in compromised patients. Fifteen ribotypes were identified. The three archetypal strains harbored different ribotypes, and only one-third of our urosepsis strains were genetically related to one of the archetypal strains. Three and 18 strains harbored three and two copies of pap, respectively, and 5 strains harbored two copies of hly. papGIII was physically linked to hly, cnf-1, and hra (reported to be PAI IIJ96-like genetic elements) in 14% of the strains. The PAI IIJ96-like domain was inserted within pheR tRNA in 11 strains and near leuX tRNA in 3 strains. Moreover, the colocalized genes cnf-1, hra, and hly were physically linked to papGII in four strains and to no pap gene in three strains. papGII and hly (reported to be PAI ICFT073-like genetic elements) were physically linked in 16 strains, pointing to a PAI ICFT073-like domain. Three strains contained both a PAI IIJ96-like domain and a PAI ICFTO73-like domain. Forty-two strains harbored papGII but not hly, in keeping with the presence of a PAI IICFT073-like domain. Only one strain harbored a PAI I536-like domain (hly only), and none harbored a PAI IJ96-like domain (papGI plus hly) or a PAI II536-like domain (papGIII plus hly). This study provides new data on the prevalence and variability of physical genetic linkage between pap and certain virulence-associated genes that are consistent with their colocalization on archetypal PAIs.

Escherichia coli is the most frequent cause of gram-negative bacterial extraintestinal infections, such as cystitis, prostatitis, pyelonephritis, bacteremia, and neonatal meningitis, in humans. Several virulence factors enhance the capacity of E. coli to cause systemic infections; unlike most commensal E. coli strains, extraintestinal isolates possess genes encoding various combinations of adhesins (P and S fimbriae), iron acquisition systems (e.g., aerobactin and yersiniabactin), host defense avoidance mechanisms (capsule or O-specific antigen), and toxins (e.g., hemolysin and cytonecrotizing factor) (13, 14, 17, 42). Genes coding for multiple virulence factors are located together on large blocks of chromosomal DNA known as pathogenicity islands (PAIs) (18).

Recent studies suggest that extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli strains belong mostly to phylogenetic group B2 and, to a lesser extent, group D (5, 8, 39). In contrast, commensal E. coli strains generally belong to phylogenetic groups A and B1 (12).

In this study, we determined the phylogenetic group, genetic diversity, and virulence gene distribution of 100 well-characterized E. coli blood isolates from adults with community-acquired urosepsis, according to host compromise status. We also sought copies of pap and hly and their direct physical linkage with certain virulence genes, consistent with their colocalization on PAIs described for archetypal uropathogenic E. coli strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

One hundred E. coli strains were recovered by blood culture from 100 consecutive adults with community-acquired pyelonephritis and bacteremia between January 1999 and April 2001 in the Paris, France, region. A spontaneous nonhemolytic mutant of one of these strains (P89-M1) was also studied.

Pyelonephritis strain CFT073 from Baltimore, Md. (kindly provided by H. L. T. Mobley, University of Maryland) (32); pyelonephritis strain 536 from Wurzburg, Germany (kindly provided by J. Hacker) (7); and pyelonephritis strain J96 from Seattle, Wash. (kindly provided by J. Hacker) (6) were used for comparison.

Clinical data.

Community-acquired bacteremia was defined as a bacteremic episode in which, at the time when the index blood sample was taken for culture, the patient was not hospitalized or had been hospitalized for less than 48 h and had not been hospitalized during the previous 28 days. Diagnostic criteria for acute pyelonephritis were dysuria, temperature of ≥38.5°C, leukocyturia of >105/ml, E. coli level of ≥105 CFU/ml in midstream urine, and no other identifiable source of infection. The following data were recorded from the patients' files: age, gender, and host compromise status (i.e., underlying medical conditions such as diabetes mellitus, cancer, immunosuppression, or uremia or underlying urological conditions such as preexisting urinary tract abnormalities, urinary tract instrumentation, or pregnancy).

Detection of virulence determinants by PCR.

All isolates were tested for seven putative virulence factor genes characteristic of extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (chuA, outer membrane heme receptor; pap, P fimbriae; sfa, S fimbriae; hly, hemolysin; cnf-1, cytotoxic necrotizing factor; aer, iron uptake system; and fyuA/irp-2, iron uptake system). In addition, the 21 cnf-1-positive isolates were screened for hra (heat-resistant agglutinin) (45). The PCR was carried out in a 20-μl volume with 2 μl of 10× buffer (ATGC Biotechnologie, Noisy-le-Grand, France), 20 pmol of each primer, a 200 μM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (ATGC Biotechnologie), and 3 μl of bacterial lysate. PCR was performed with a Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp 9600 thermal cycler with MicroAm tubes under the following conditions: denaturation for 5 min at 94°C; 30 cycles of 10 s at 94°C, 20 s at 55°C, and 30 s at 72°C; and a final extension step for 7 min at 72°C. The primers used for PCR (Table 1) were chosen from previously published sequences or were designed for this study (5, 9, 23, 31, 33, 38, 44).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used to amplify virulence-associated genes

| Primer designation | Primer sequence | Target | Size of PCR product (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| chuA.1 | 5′-GACGAACCAACGGTCAGGAT-3′ | chuA | 279 | (9) |

| chuA.2 | 5′-TGCCGCCAGTACCAAAGACA-3′ | (9) | ||

| yjaA.1 | 5′-TGAAGTGTCAGGAGACGCTG-3′ | yjaA | 211 | (9) |

| yjaA.2 | 5′-ATGGAGAATGCGTTCCTCAAC-3′ | (9) | ||

| TspE4C2.1 | 5′-GAGTAATGTCGGGGCATTCA-3′ | TspE4.C2 | 152 | (9) |

| TspE4C2.2 | 5′-CGCGCCAACAAAGTATTACG-3′ | (9) | ||

| papC.1 | 5′-GACGGCTGTACTGCAGGGTGTGGCG-3′ | papC | 328 | (33) |

| papC.2 | 5′-ATATCCTTTCTGCAGGGATGCAATA-3′ | (33) | ||

| papG.I.1 | 5′-TCGTGCTCAGGTCCGGAATTT-3′ | papGI | 461 | (23) |

| papG.I.2 | 5′-TGGCATCCCCCAACATTATCG-3′ | (23) | ||

| papG.II.1 | 5′-GGGATGAGCGGGCCTTTGAT-3′ | papGII | 190 | (23) |

| papG.II.2 | 5′-CGGGCCCCCAAGTAACTCG-3′ | (23) | ||

| papG.III.1 | 5′-GGCCTGCAATGGATTTACCTGG-3′ | papGIII | 258 | (23) |

| papG.III.2 | 5′-CCACCAAATGACCATGCCAGAC-3′ | (23) | ||

| papG.II/III.1 | 5′-GACTCTTTCTGTGTCTTGCG-3′ | papGII + papGIII | 254 | This study |

| papG.II/III.2 | 5′-GAACCAGATAGTACTCCTGG-3′ | This study | ||

| sfa.1 | 5′-CTCCGGAGAACTGGGTGCATCTTAC-3′ | sfa/foc | 410 | (33) |

| sfa.2 | 5′-CGGAGGAGTAATTACAAACCTGGCA-3′ | (33) | ||

| hly.1 | 5′-AGGTTCTTGGGCATGTATCCT-3′ | hlyC | 556 | (5) |

| hly.2 | 5′-TTGCTTTGCAGACTGCAGTGT-3′ | (5) | ||

| cnf1.1 | 5′-CAGTGACCGGATCTCCGTTAT-3′ | cnf-1 | 230 | (38) |

| cnf1.2 | 5′-CGTGTAATTCTTCTGTACTTCC-3′ | (38) | ||

| aer.1 | 5′-AAACCTGGTTTACGCAACTGT-3′ | aer (iucC) | 269 | (5) |

| aer.2 | 5′-ACCCGTCTGCAAATCATGGAT-3′ | (5) | ||

| fyuA.1 | 5′-TGATTAACCCCGCGACGGGAA-3′ | fyuA | 780 | (31) |

| fyuA.2 | 5′-CGCAGTAGGCACGATGTTGTA-3′ | (44) | ||

| irp2.1 | 5′-AAGGATTCGCTGTTACCGGAC-3′ | irp-2 | 280 | (44) |

| irp2.2 | 5′-TCGTCGGGCAGCGTTTCTTCT-3′ | (44) | ||

| hra.1 | 5′-CAGAAAACAACCGGTATCAG-3′ | hra | 260 | This study |

| hra.2 | 5′-ACCAAGCATGATGTCATGAC-3′ | This study | ||

| pheR.1 | 5′-GCCGCAATCTTAAGCAGTTG-3′ | pheR | 350 | This study |

| pheR.2 | 5′-GCACGACATTTCACGTCAGT-3′ | This study | ||

| yjgB.1 | 5′-ACCTTGCTCGCAGTTGATCT-3′ | leuX (yjgB) | This study |

PCR phylogenetic grouping.

The phylogenetic group was determined by using a previously described PCR-based method (9). Briefly, two-step triplex PCR was performed directly on 3 μl of bacterial lysate with the primer pairs chuA.1-chuA.2, yjaA.1-yjaA.2, and TspE4C2.1-TspE4C2.2 (Table 1). The PCR steps were as follows: denaturation for 4 min at 94°C, 30 cycles of 5 s at 94°C and 10 s at 59°C, and a final extension step for 5 min at 72°C.

Ribotyping.

Total E. coli DNA was prepared as previously described (3, 4) and then digested with HindIII and subjected to Southern blotting with E. coli 16S rRNA plus 23S rRNA as the probe (2). The probe was labeled by random oligonucleotide priming with a mixture of hexanucleotides (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Saclay, France) and cloned Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Gibco BRL, Cergy Pontoise, France) in the presence of 0.35 mM digoxigenin-11-deoxyuridine-5′ triphosphate (Roche, Meylan, France). Chemiluminescence was detected as previously reported (3).

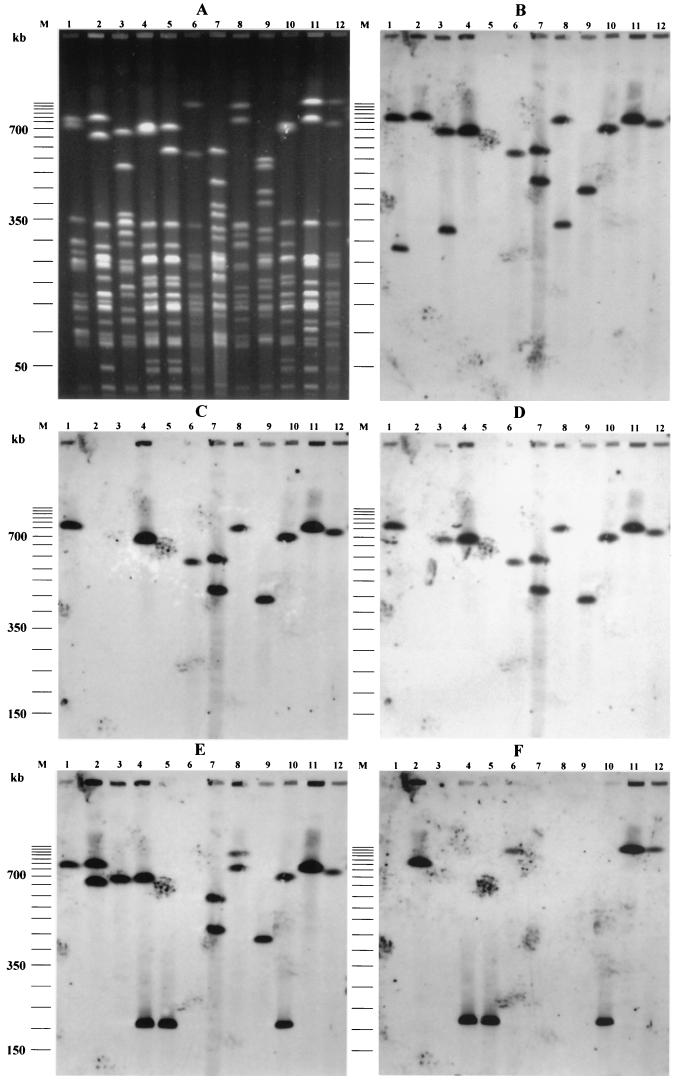

PFGE and Southern blot hybridization.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was used to determine the physical locations of genes representative of PAI IIJ96-like genetic elements (papGIII, hly, cnf-1, and hra) (45) and of PAI ICFTO73-like genetic elements (papGII and hly) (32). Thirty-four hly-positive strains and the three archetypal strains J96, CFT073, and 536 were subjected to PFGE as previously described (15). In brief, bacterial cells were embedded in agarose, lysed with detergent and proteinase K (Sigma-Aldrich, St Quentin Fallavier, France), and digested with NotI (Roche). PFGE digests were transferred to nylon membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled probes generated from the primers specific for each gene (Table 1) as recommended by the manufacturer (Roche).

Determination of the copy numbers of virulence genes.

Southern blots used for ribotyping were also used to determine the papG, aer, and hly copy numbers by hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled probes. Strains harboring more than one copy of these genes were subjected to another round of Southern blotting after digestion with EcoRI, followed by hybridization with the same probes.

Localization of the PAI IIJ96-like junctions on the K-12 chromosome map.

Long-range PCR was performed with the Expand Long Template PCR system (Roche) to amplify the DNA region between pheR or leuX and hra, using the same primers as for standard PCR (Table 1). The PCR was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions in a 30-μl volume with 3 μl of buffer 3, 12 pmol of each primer, a 500 μM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 2.5 U of Taq mix, and 200 ng of genomic DNA.

Capsular typing.

K1 antigen was detected with an antiserum to a Neisseria meningitidis group B strain (11).

Statistical analysis.

Fisher's exact test was used. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patients' characteristics.

Eighty-one of the 100 patients were women. The median age was 66 years (range, 19 to 99 years). The median ages of the male and female patients were 67 and 64 years, respectively. Fifty-three percent of the patients were over 65 (81% of males and 47% of females). Forty-one patients were noncompromised, and 59 had one or more host compromise factors (Table 2). The median age was 58 years in the noncompromised group and 66 years in the compromised group.

TABLE 2.

Host characteristics according to papG alleles and phylogenetic group

| Associated host characteristic (n) | No. (%) of strains

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With papG allele:

|

papC positive papG negative (n = 5) | pap negative (n = 22) | From phylogenetic group:

|

||||||

| II only (n = 59) | III only (n = 5) | II + III (n = 9) | B2 (n = 61) | D (n = 27) | A (n = 11) | B1 (n = 1) | |||

| Noncompromise (41) | 32a (78) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 1 (2) | 4b (10) | 23 (56) | 15 (37) | 3 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Any compromise (59) | 27 (46) | 3 (5) | 7 (12) | 4 (7) | 18 (30) | 38 (64) | 12 (20) | 8 (14) | 1 (2) |

| Diabetes (24) | 16 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 15 | 6 | 3 | 0 |

| Cancer (6) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Immunosuppression (11) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Uremia (14) | 6 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Any urological compromise (8) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Urinary tract instrumentation (5) | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Pregnancy (6) | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

P = 0.002 versus any host compromise.

P = 0.02 versus any host compromise.

Phylogenetic analysis and ribotyping.

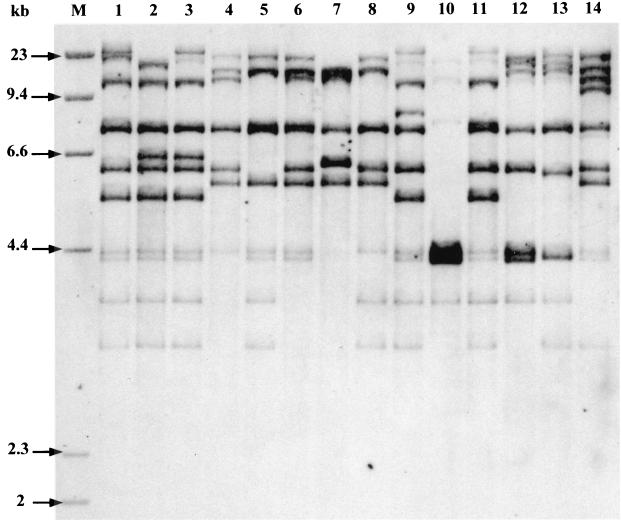

Sixty-one, 27, 11, and 1% of the isolates belonged to phylogenetic groups B2, D, A, and B1, respectively (Tables 2 and 3). Fifteen ribotypes (I to XV) were identified among the 100 isolates. The numbers of ribotypes in groups B2, D, A, and B1 were 6, 5, 3, and 1, respectively. However, four ribotypes (I, n = 20; II, n = 19; III, n = 12; and IV, n = 12) accounted for 63% of the isolates. Five ribotypes were represented by seven or more isolates, and two ribotypes were represented by a single isolate (Fig. 1; Table 4). Representative ribotypes are shown in Fig. 1. The archetypal strains CFT073, 536, and J96 harbored ribotypes I, III, and XI, respectively, and could thus be considered genetically related to, respectively, 20, 12, and 2 of our strains.

TABLE 3.

Distribution of virulence factors in E. coli urosepsis strains according to phylogenetic group

| Group (n) | No. (%) with:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| papC | papG | papG | papG | sfa/foc | aer | hly | cnf-1 | fyuA/irp-2 | |

| Class II | Class III | Class II + III | |||||||

| Total (100) | 78 | 59 | 5 | 9 | 26 | 80 | 34 | 21 | 92 |

| A (11) | 5 (45) | 1 (9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (55) | 0 | 0 | 11 (100) |

| B1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D (27) | 21 (78) | 20 (74) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26 (96) | 1 (37) | 0 | 20 (74) |

| B2 (61) | 52 (85) | 38 (62) | 5 (8) | 9 (15) | 26 (43) | 48 (79) | 33 (54) | 21 (34) | 61 (100) |

FIG. 1.

Representative ribotypes after HindIII digestion of the 100 urosepsis strains. Lane 1, ribotype I (20 strains, group B2); lane 2, ribotype II (19 strains, group B2); lane 3, ribotype III (12 strains, group B2); lane 4, ribotype IV (12 strains, group D); lane 5, ribotype V (7 strains, group D); lane 6, ribotype VI (6 strains, group A); lane 7, ribotype VII (4 strains, group A); lane 8, ribotype VIII (4 strains, group D); lane 9, ribotype IX (4 strains, group B2); lane 10, ribotype X (4 strains, group B2); lane 11, ribotype XI (2 strains, group B2); lane 12, ribotype XII (2 strains, group D); lane 13, ribotype XIII (2 strains, group D); lane 14, ribotype XIV (1 strain, group B1); lane M, molecular size marker.

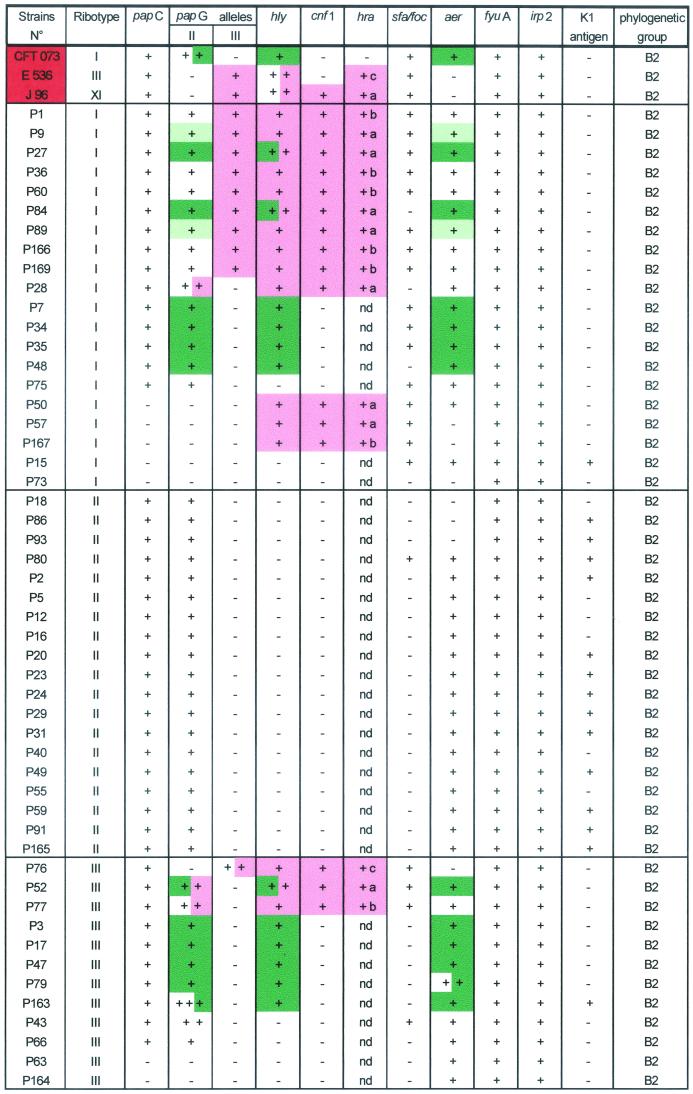

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of the 100 E. coli urosepsis isolates and of the three archetypal strainsa

Physically linked genes on PFGE are represented in the same color (only hly-positive strains were tested). nd, not done; number of (+), number of copies of the gene. a, PCR hra/pheR fragment size, 5.2 kb; b, PCR hra/pheR fragment size, 7.5 kb; c, PCR hra/leuX fragment size, 8 kb; d, PCR hra/leuX fragment size, 4.5 kb.

Prevalence of virulence factors.

papC was found in 78 isolates, 73 of which harbored papGII and/or papGIII. The most prevalent papG allele was allele II (68%) (Tables 3 and 4). Allele III was present in only 14% of strains, and none of the strains contained papG allele I. fyuA and irp-2 were detected in 92% of the isolates. sfa/foc, aer, hly, and cnf-1 were found in 2,680, 34, and 21% of the isolates, respectively. Eighteen isolates had two copies of pap, and two strains had three copies. Five strains had two copies of hly, and five strains had two copies of aer (Table 4). papG allele III, sfa/foc, and cnf-1 were restricted to phylogenetic group B2 strains. K1 antigen was detected in 20 isolates, of which 18 belonged to phylogenetic group B2 and 13 belonged to ribotype II.

Prevalence and physical location of virulence gene combinations.

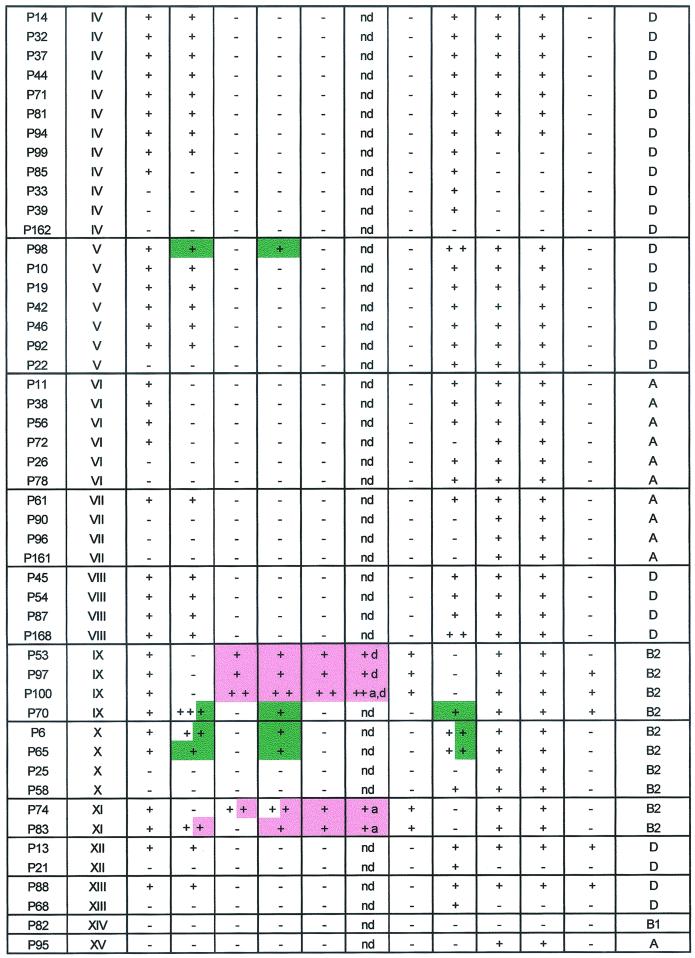

As combinations of some virulence genes with pap and/or hly may suggest the presence of PAIs described for archetypal strains (18, 19), we examined various combinations of papG and virulence factors. PFGE was applied to strains with putative PAI IIJ96-like domains (papGIII, hly, cnf-1, hra positive) and putative PAI ICFT073-like domain (papGII, hly positive). Southern blotting of PFGE gels showed that hly was physically linked to cnf-1 and hra in 21 strains. These three genes were linked to papGIII in 14 strains and to papGII in 4 strains (P28, P52, P77, and P83) and were found alone in 3 strains (P50, P57, and P167) (Table 4). The presence of colocalized PAI IIJ96-like genetic elements in 14 strains suggested the presence of a PAI similar to PAI IIJ96. Interestingly, one strain (P100) bore two copies of the physically linked combination of papGIII, hly, cnf-1, and hra (Fig. 2). hly was physically linked to papGII alone in 16 strains. Three of these latter strains also harbored another copy of hly, linked to cnf-1 and hra. The smallest NotI DNA fragment containing papGII and hly was approximately 200 kb long, and those containing hly, cnf-1, and hra were about 280 kb long (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

PFGE patterns of NotI-digested genomic DNAs (A) and Southern hybridization with DNA probes specific for hly (B), cnf-1 (C), hra (D), papGII/III (E), and aer (F) of archetypal and representative strains. Lanes 1, J96; lanes 2, CFT073; lanes 3, 536; lanes 4, P89; lanes 5, P89-M1; lanes 6, P50; lanes 7, P100; lanes 8, P74; lanes 9, P53; lanes 10, P9; lanes 11, P166; lanes 12, P28; lanes M, molecular size marker (50-kb DNA ladder).

During subculture, a nonhemolytic colony of P89 occurred spontaneously. This mutant, designated P89-M1, was further investigated. PFGE of DNA digested with NotI showed that P89-M1 had a DNA fragment approximately 120 kb shorter than that of the wild-type strain (700 versus 580 kb) (Fig. 2). PFGE Southern blot hybridization with papGII/GIII, hly, cnf-1, and hra probes showed that all of these genes (physically linked on the 700-kb NotI DNA restriction fragment) were absent from the 580-kb DNA fragment (Fig. 2). This demonstrated that the genes characteristic of PAI IIJ96 were clustered on a DNA fragment of approximately 120 kb on the P89 chromosome and were spontaneously deleted en bloc. These characteristics are in accordance with those described for PAI IIJ96, demonstrating that strain P89 harbors a PAI similar to PAI IIJ96 (6, 45).

To determine whether the PAI IIJ96-like domain found in 14 strains was inserted within the pheR tRNA gene, as described for strain J96, PCR was performed with primers homologous to the flanking sequence of the pheR tRNA gene (Table 1). DNAs from 11 of these 14 strains could not be amplified, suggesting that their pheR tRNA genes were interrupted. To confirm that this interruption was caused by the insertion of a PAI IIJ96-like domain, we used a long-range PCR approach. Amplification with primers chosen within the sequence of hra (hra.1) (a gene located at the end of the PAI) (45) and the flanking region of pheR tRNA (pheR.1) yielded a fragment of 5.2 kb with strain J96. Thus, long-range PCR was applied to each of the 11 strains, and 6 and 5 of them, respectively, yielded fragments of 5.2 and 7.5 kb (data not shown). Regarding the three strains (P76, P53, and P97) in which the pheR tRNA gene was not interrupted, we speculated that the leucine X tRNA region was the other insertion site of the PAI IIJ96-like domain. This assumption was based on work by Hacker et al. (18), who described a PAI on strain 536 which may resemble PAI IIJ96 (papGIII positive, hly positive, and cnf-1 negative but having the cnf-1 flanking sequence) and is inserted in the vicinity of the leucine X tRNA region. As hra was also present in strain 536 and physically linked to papGIII and hly (see below) (Fig. 2), long-range PCR between hra and the leucine X region (yjgB gene) (Table 1) was performed with this strain and yielded a fragment of 8 kb. Long-range PCR was also applied to the three strains (P76, P53, and P97) with positive pheR amplification and gave fragments of 8, 4.5, and 4.5 kb, respectively. With strain P100, harboring two PAI IIJ96-like domains, long-range PCR (hra.1-pheR.1 and hra.1-yjgB.1) gave fragments of 5.2 and 4.5 kb, respectively. Thus, four strains had a PAI IIJ96-like domain near the leuX tRNA gene.

Finally, as the colocalized genes hra, cnf-1, and hly, found in seven strains lacking the papGIII allele (strains P50, P57, P83, P167, P28, P52, and P77), may correspond to a modified PAI IIJ96-like domain, we analyzed these strains in the same way. We found that the pheR tRNA genes were interrupted in all seven strains. Long-range PCR (hra.1-pheR.1) yielded products of 5.2 and 7.5 kb with five and two strains, respectively (Table 4).

Using the Blattner website (www.genome.wisc.edu/html/upec.html), which gives the sequence of CFT073 (16, 32), we found that hly and papGII were present on a 124-kb fragment inserted between pheV tRNA and yghD genes on the K-12 chromosome map and that the aer operon was present in this fragment. Thus, as aer was more frequent in papGII-positive isolates (64 of 68 [93%]) than in papGII-negative isolates (17 of 32 [53%]) (P < 0.01) (Table 4), we investigated the physical linkage of aer and papGII in the strains subjected to PFGE. Among the 26 strains harboring aer, pap and aer were physically linked in 17. Moreover, papGII, hly, and aer were physically linked in 15 of these strains. The other two strains harbored papGII and aer, but not hly, colocalized on the same DNA macrorestriction fragment of 210 kb (Fig. 2). Finally, in only one isolate (P74) hly was not physically linked to pap. Interestingly, 42 isolates harbored papGII without hly or cnf-1, but 39 of these isolates also harbored aer (Table 4).

PFGE Southern blots of representative strains carrying the hly and cnf-1 genes (P9, P28, P50, P53, P74, P89, P100, and P166), as well as mutant P89-M1 and the archetypal strains J96, CFT073, and 536, are shown in Fig. 2. As expected, hly was coupled to papGIII, cnf-1, and hra on a 760-kb NotI DNA fragment in strain J96 and was present alone on a 290-kb NotI DNA fragment. Strain CFT073 harbored two papGII alleles, one of which was physically linked to hly and aer on an 800-kb NotI DNA fragment. Interestingly, strain 536 harbored a papGIII gene that was physically linked, on a 680-kb NotI DNA fragment, with hly (as expected) and also hra (Fig. 2).

Phylogenetic group versus host characteristics.

The phylogenetic group distribution did not differ significantly between compromised and noncompromised patients (Table 2).

papG alleles versus host characteristics.

Strains bearing only allele II were more common in noncompromised patients than in compromised patients (P = 0.002) (Table 2). In contrast, papG-negative strains were significantly more frequent among compromised patients (P = 0.005) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

We used molecular methods to characterize a set of community-acquired urosepsis E. coli isolates obtained in France and to compare these strains with archetypal uropathogenic strains. The diversity of the isolates was shown by the presence of 15 ribotypes, although a small number of ribotypes accounted for most of the isolates. Such oligoclonality in extraintestinal E. coli has previously been reported (20, 35, 36). One-third of isolates were accounted for by the three ribotypes to which the three archetypal strains belonged; the most frequent, ribotype I (n = 20), was harbored by strain CFT073, which is the only urosepsis strain among the three archetypal strains (32). However, isolates belonging to the second most frequent ribotype (ribotype II) were genetically unrelated to any of the three archetypal strains and were homogeneous with respect to their virulence factor profiles and genetic background. Indeed, all isolates belonging to ribotype II (n = 19) carried papGII, fyuA, and irp-2 and lacked both hly and cnf-1, suggesting close genetic relatedness.

Most uropathogenic E. coli strains are reported to belong to phylogenetic group B2 (20, 25, 40), but the distribution of community-acquired urosepsis isolates among the other phylogenetic groups (A, B1, and D) has not previously been assessed. Using a triplex PCR method (9), we found that most of our isolates belonged to group B2 (n = 61) and, to a lesser extent, group D (n = 27). The fourth most frequent ribotype (ribotype IV, 12 strains) belonged to group D. Moreover, 11 strains and 1 strain, respectively, belonged to the nonpathogenic groups A and B1. This is in keeping with our previous data on extraintestinal E. coli: 68% of neonatal E. coli meningitis isolates belonged to phylogenetic group B2, and 22, 6, and 4% belonged to groups D, A, and B1, respectively (5). Very recently, Johnson et al. (26), studying E. coli bacteremia strains from diverse sources, found a prevalence of groups A, B2, and D similar to that observed here. However, those authors found a significantly higher proportion of B1 strains (19 of 189 versus 1 of 100; P = 0.006), possibly because of the heterogeneity of the primary sites of infection from which their strains were derived. It has been reported that most E. coli blood isolates from immunocompromised hosts exhibit the B1 carboxylesterase phenotype, defined as belonging to groups other than B2, and are devoid of virulence factors (25, 27, 40). Overall, our results agree with these latter reports, as group A and B1 strains were more frequent in compromised patients than in noncompromised patients (15.2 versus 7.3%).

Few authors have studied the prevalence of virulence genes in community-acquired urosepsis E. coli isolates (29, 31). The proportions of isolates harboring papC, cnf-1, hly, and aer in our study (78, 21, 34, and 80%, respectively) are comparable to those found in blood isolates by Johnson and Stell (77, 16, 41, and 80%, respectively) (31). The prevalence of these genes was different in bacteremia isolates studied by Hilali et al. (20) and Maslow et al. (35), but this may be explained by the diversity of the primary source of infection in the latter studies.

Geographic location may also influence the distribution of papG alleles in E. coli strains causing bacteremia (22, 24, 37). Allele II was the predominant papG allele among E. coli blood isolates from adults in Seattle, Wash. (22); Long Beach, Calif. (24); Nairobi, Kenya (24); and Sweden (22, 37). In contrast, papG allele III was found by Johnson et al. in a majority of isolates from Boston, Mass. (24). Allele II predominated (68%) over allele III in our E. coli strains isolated from French adults with bacteremia and urinary tract infection. Moreover, the papG allele distribution differed according to host compromise status. The observed associations between papGII and noncompromised hosts and between papG negativity and host compromise in our study are consistent with previous reports (22, 37). Host compromise factors facilitate bloodstream invasion by papG-negative E. coli strains (21). Five percent of our strains were positive for papC and negative for papG alleles I, II, and III, in keeping with previous reports (26, 34, 37). This suggests that another allele may be present or that papG may be deleted. Interestingly, four of these five strains belonged to phylogenetic group A.

Extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli isolates are known to carry large chromosomal regions required for virulence; these so-called PAIs have been defined in uropathogenic strains 536, J96, and CFT073. We found various combinations of the genes studied here. The concomitant presence of fyuA/irp-2 (encoding an iron uptake system representative of the Yersinia high-pathogenicity island [HPI]) (1) was found in 92% of our strains and thus seems to be characteristic of E. coli blood isolates. A similar high level has previously been found in E. coli urosepsis isolates (31, 43). fyuA/irp-2 was found in all of our isolates belonging to phylogenetic group A. Similarly, these genes have been found in all E. coli neonatal meningitis strains belonging to group A (10). In contrast, fyuA/irp-2 was found in only 32% of ECOR group A strains (10) and in 30% of fecal isolates (44). As phylogenetic group A strains are principal members of the commensal flora (12), our results suggest that commensal intestinal E. coli carrying fyuA/irp-2 would have a selective advantage for causing bacteremia, although we did not perform functionality experiments. Johnson and Stell have suggested that HPI may constitute a useful target for preventive intervention (31). Likewise, from a practical point of view, the absence of fyuA/irp-2 in a urinary tract isolate would tend to exclude the risk of bacteremia in noncompromised patients. Finally, the association of papC with fyuA/irp-2 could be the minimal prerequisite for bacterial passage from a renal focus of infection into the bloodstream of noncompromised patients.

The association of papGIII, hly, hra, and cnf-1 was observed in 14% of our strains, and these genes were located on a single DNA macrorestriction fragment. A similar prevalence of the physically linked combination of papC, hly, and cnf-1 (19%) in E. coli isolates from cancer patients with septicemia has been reported (20). However, the authors of that study did not test for papG alleles. All of our strains bearing this combination belonged to group B2. The association of these four virulence genes, reported to be PAI IIJ96-like genetic elements as in reference strain J96 (6), suggests the presence of a PAI IIJ96-like domain in 14 of our 100 strains. In one of these strains (P89), the spontaneous en bloc deletion of these four genes provides strong evidence for the presence of such a PAI. Moreover, we found that the insertion site of the PAI IIJ96-like domain was within pheR tRNA (as in reference strain J96) in 11 strains (including P89 and P100) and near leuX tRNA in four strains (including P100, which carried two copies of these four genes). Interestingly, we found that seven strains harbored hly, hra, and cnf-1, colocalized without papGIII and inserted within pheR tRNA. Among these seven strains, four carrying the hly, cnf-1, and hra association harbored papGII instead of papGIII on the same fragment. One of these four strains was genetically related to J96. This may point to a PAI IIJ96-like domain, with allelic exchange of papG or the presence of papG allele II at another site and deletion of papGIII (31). In favor of the first possibility is the presence of papGII, hly, cnf-1, and hra on a 280-kb fragment in strain P52 (data not shown). The second possibility is supported by the fact that three of our strains carried the combination of hly, cnf-1, and hra on the same restriction fragment, without pap. Spontaneous deletion of pap has been documented (17). A similar combination of cnf-1 and hly without pap was described by Hilali et al. for 4% of their E. coli blood isolates (20). It has been suggested that E. coli PAIs undergo additional recombination processes that lead to additions or deletions of genes within the PAI (18, 26, 45). These results, combined with the differences in PAI sizes and site-specific insertion that we found, point to genetic plasticity of PAI IIJ96-like domains. However, the consistent physical linkage of cnf-1, hly, and hra that we found in 21 strains and the statistical association between cnf-1 and hly found by other authors suggest that this cluster of three genes may constitute the backbone of the PAI and serve as specific markers of the PAI IIJ96-like domain. PAI IIJ96-like domains were found exclusively in group B2. This contrasts with the distribution of HPI in groups B2, D, and A and suggests that certain PAIs may be specifically restricted to particular phylogenetic groups. Moreover, our results suggest that the PAI IIJ96-like domain is not restricted to a single clone, as we found it in four different ribotypes, in contrast to other reports (28, 30) (Table 4). Only two strains were genetically related to J96 by ribotyping, implying that archetypal strain J96 is a rare cause of urosepsis in France.

Genetic linkage of papGII to the hly locus , suggestive of the presence of a PAI ICFT073-like domain (16, 32), was found in 16% of our isolates, a prevalence lower than that previously reported (16). Three of these strains also harbored a PAI IIJ96-like domain (Table 2). Fifteen of these 16 strains also harbored the aer locus colocalized with papGII and hly. The smallest NotI DNA fragment containing the three genes was found in two strains and was approximately 200 kb long. Interestingly, in two strains (P9 and P89), papGII and aer were physically linked (without hly) on a NotI DNA fragment of 210 kb. This, combined with the fact that 93% of strains harboring papGII but not hly were aer positive, whereas aer is found at a significantly lower prevalence (53%) in papGII-negative strains, strongly suggests the presence of either a new PAI containing papGII and aer or a PAI ICFT073-like domain from which hly has been deleted. However this needs to be supported by further experiments demonstrating the en bloc deletion of the genes belonging to the putative PAI. Further studies are under way to confirm our hypothesis.

Finally, three of our strains carried papGII without hly, aer, or cnf-1, which is compatible with a PAI IICFT073-like domain (41), and one strain harbored hly alone, which is compatible with a PAI I536-like domain (7, 18).

The distribution of virulence factors in our E. coli ribotype I urosepsis isolates is interesting. Indeed, the combination of papGII and papGIII was confined to ribotype I, while papGIII alone was present in isolates belonging to three other ribotypes. Previous studies have shown an association between serogroup 02 and papGII plus papGIII status (22, 24). The fact that papGII alone was present in ribotype I, in contrast to papGIII, suggests that papGII was acquired first by ribotype I strains. Thus, the combination of papGIII, hly, cnf-1, and hra (PAI IIJ96-like domain) may have been acquired secondarily on a papGII-positive ribotype I background.

In conclusion, we characterized a collection of E. coli urosepsis isolates from French adults with respect to their phylogenetic background and virulence factor profile, in comparison with archetypal uropathogenic isolates. We found that most of the isolates belonged to phylogenetic groups B2 and D and harbored papG allele II and the aer and fyuA/irp-2 genes. This study provides data on prevalence and phylogenetic distribution indicating direct genetic linkage between pap and certain virulence-associated genes, consistent with colocalization on PAIs, that have previously been shown to exhibit statistical associations in other E. coli strain collections. Moreover, we show the variability of such gene associations, suggesting the plasticity of archetypal PAIs, even if some gene associations may form the backbone of certain PAIs, such as the hly, cnf-1, and hra association in the PAI IIJ96-like domain. PAI IIJ96-like and PAI ICFT073-like domains were found in 21 and 16% of our strains, respectively, and three strains harbored both. Only one strain harbored a PAI I536-like domain, and none harbored a PAI IJ96-like or PAI II536-like domain, suggesting that these PAIs may not be important in the urosepsis mechanism.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Programme de Recherche Fondamentale en Microbiologie, Maladies Infectieuses et Parasitaires (Appel d'offre 1998), “Recherche de déterminants génétiques de pathogénicité chez E. coli K1 responsable de méningite néonatale.”

REFERENCES

- 1.Bach, S., A. de Almeida, and E. Carniel. 2000. The Yersinia high-pathogenicity island is present in different members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 183:289-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bingen, E., E. Denamur, N. Lambert-Zechovsky, C. Boissinot, N. Brahimi, Y. Aujard, P. Blot, and J. Elion. 1992. Analysis of DNA restriction-fragment length polymorphism extends the evidence for breast milk transmission in Streptococcus agalactiae late-onset neonatal infection. J. Infect. Dis. 165:569-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bingen, E., E. Denamur, N. Lambert-Zechovsky, A. Bourdois, P. Mariani-Kurkdjian, J. P. Cezard, J. Navarro, and J. Elion. 1991. DNA restriction-fragment length polymorphism differentiates crossed from independent infections in nosocomial Xanthomonas maltophilia bacteremia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:1348-1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bingen, E., E. Denamur, B. Picard, P. Goullet, N. Lambert-Zechovsky, N. Brahimi, J. C. Mercier, F. Beaufils, and J. Elion. 1992. Molecular epidemiology unravels the complexity of neonatal Escherichia coli acquisition in twins. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:1896-1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bingen, E., B. Picard, N. Brahimi, S. Mathy, P. Desjardins, J. Elion, and E. Denamur. 1998. Phylogenetic analysis of Escherichia coli strains causing neonatal meningitis suggests horizontal gene transfer from a predominant pool of highly virulent B2 group strains. J. Infect. Dis. 177:642-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blum, G., V. Falbo, A. Caprioli, and J. Hacker. 1995. Gene clusters encoding the cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 1, Prs-fimbriae, and α-hemolysin form of the pathogenicity island II of the uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain J96. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 126:189-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blum, G., M. Ott, A. Lischwski, A. Ritter, H. Imrich, H. Tschäpe, and J. Hacker. 1994. Excision of large DNA regions termed pathogenicity islands from tRNA-specific loci in the chromosome of an Escherichia coli wild-type pathogen. Infect. Immun. 62:606-614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd, E. F., and D. L. Hartl. 1998. Chromosomal regions specific to pathogenic isolates of Escherichia coli have a phylogenetically clustered distribution. J. Bacteriol. 180:1159-1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clermont, O., S. Bonacorsi, and E. Bingen. 2000. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4555-4558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clermont, O., S. Bonacorsi, and E. Bingen. 2001. The Yersinia high-pathogenicity island is highly predominant in virulence-associated phylogenetic groups of Escherichia coli. FEMS. Microbiol. Lett. 196:153-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cross, A., I. Orskov, F. Orskov, J. Sadoff, and P. Gemski. 1984. Identification of K1 Escherichia coli antigen. J. Clin. Microbiol. 20:302-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duriez, P., O. Clermont, S. Bonacorsi, E. Bingen, A. Chaventre, J. Elion, B. Picard, and E. Denamur. 2001. Commensal Escherichia coli isolates are phylogenetically distributed among geographically distinct human populations. Microbiology 6:1671-1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenstein, B. I., and G. W. Joes. 1998. The spectrum of infections and pathogenic mechanisms of Escherichia coli. Adv. Intern. Med. 33:231-252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finlay, B. B., and S. Falkow. 1997. Common themes in microbial pathogenicity revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:136-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grothues, D., and B. Tümmler. 1991. New approaches in genome analysis by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: application to the analysis of Pseudomonas species. Mol. Microbiol. 5:2763-2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guyer, D. M., J. S. Kao, and H. L. T. Mobley. 1998. Genomic analysis of a pathogenicity island in uropathogenic Escherichia coli CFT073: distribution of homologous sequences among isolates from patients with pyelonephritis, cystitis, and catheter-associated bacteriuria and from fecal samples. Infect. Immun. 66:4411-4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hacker, J., L. Bender, M. Ott, J. Wingender, B. Lund, R. Marre, and W. Goebel. 1990. Deletions of chromosomal regions coding for fimbriae and hemolysins occur in vitro and in vivo in various extraintestinal Escherichia coli isolates. Microb. Pathog. 8:213-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hacker, J., G. Blum-Oehler, B. Janke, G. Nagy, and W. Goebel. 1999. Pathogenicity islands of extraintestinal Escherichia coli, p. 59-76. In J. B. Kaper and J. Hacker (ed.), Pathogenicity islands and other mobile virulence elements. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 19.Hacker, J., G. Blum-Oehler, I. Muhldorfer, and H. Tschape. 1997. Pathogenicity islands of virulent bacteria: structure, function and impact on microbial evolution. Mol. Microbiol. 23:1089-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hilali, F., R. Ruimy, P. Saulnier, C. Barnabé, C. Le Bouguenec, M. Tibayrenc, and A. Andremont. 2000. Prevalence of virulence genes and clonality in Escherichia coli strains that cause bacteremia in patients. Infect. Immun. 68:3983-3989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson, J. R. 1991. Virulence factors in Escherichia coli urinary tract infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4:80-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson, J. R. 1998. papG alleles among Escherichia coli strains causing urosepsis: associations with other bacterial characteristics and host compromise. Infect. Immun. 66:4568-4571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson, J. R., and J. J. Brown. 1996. A novel multiply-primed polymerase chain reaction assay for identification of variant papG genes encoding the Gal (α1-4)Gal-binding PapG adhesins of Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Dis. 173:920-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson, J. R., J. J. Brown, and J. N. Maslow. 1998. Clonal distribution of the three alleles of the Gal (α1-4) Gal-specific adhesin gene papG among Escherichia coli strains from patients with bacteremia. J. Infect. Dis. 177:651-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson, J. R., P. Goullet, B. Picard, S. L. Moseley, P. L. Roberts, and W. E. Stamm. 1991. Association of carboxylesterase B electrophoretic pattern with presence and expression of urovirulence factor determinants and antimicrobial resistance among strains of Escherichia coli that cause urosepsis. Infect. Immun. 59:2311-2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson, J. R., T. T. O'Bryan, M. Kuskowski, and J. N. Maslow. 2001. Ongoing horizontal and vertical transmission of virulence genes and papA alleles among Escherichia coli blood isolates from patients with diverse-source bacteremia. Infect. Immun. 69:5363-5374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson, J. R., I. Orskov, F. Orskov, P. Goullet, B. Picard, S. L. Moseley, P. L. Roberts, and W. E. Stamm. 1994. O, K, and H antigens predict virulence factors, carboxylesterase B pattern, antimicrobial resistance, and host compromise among Escherichia coli strains causing urosepsis. J. Infect. Dis. 169:119-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson, J. R., T. A. Russo, F. Scheutz, J. J. Brown, L. Zhang, K. Palin, C. Rode, C. Bloch, C. F. Marrs, and B. Foxman. 1997. Discovery of disseminated J96-like strains of uropathogenic Escherichia coli O4:H5 containing genes for both PapG (J96) (class I) and PrsG (J96) (class III) Gal(α1-4) Gal-binding adhesins. J. Infect. Dis. 175:983-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson, J. R., T. A. Russo, P. I. Tarr, U. Carlino, S. S. Bilge, J. C. Vary, Jr., and A. L. Stell. 2000. Molecular epidemiological and phylogenetic associations of two novel putative virulence genes, iha and iroN (E. coli), among Escherichia coli isolates from patients with urosepsis. Infect. Immun. 68:3040-3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson, J. R., A. E. Stapleton, T. A. Russo, F. Scheutz, J. J. Brown, and J. N. Maslow. 1997. Characteristics and prevalence within serogroup O4 of a J96-like clonal group of uropathogenic Escherichia coli O4:H5 containing the class I and class III alleles of papG. Infect. Immun. 65:2153-2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson, J. R., and A. L. Stell. 2000. Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J. Infect. Dis. 181:261-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kao, J. S., D. M. Stucker, J. W. Warren, and H. L. T. Mobley. 1997. Pathogenicity island sequences of pyelonephritogenic Escherichia coli CFT073 are associated with virulent uropathogenic strains. Infect. Immun. 65:2812-2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le Bouguenec, C., M. Archambaud, and A. Labigne. 1992. Rapid and specific detection of the pap, afa, and sfa adhesin-encoding operons in uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains by polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:1189-1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marklund, B. I., J. M. Tennent, E. Garcia, A. Hamers, M. Baga, F. Lindberg, W. Gaastra, and S. Normark. 1992. Horizontal gene transfer of the Escherichia coli pap and prs pili operons as a mechanism for the development of tissue-specific adhesive properties. Mol. Microbiol. 6:2225-2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maslow, J. N., T. S. Whittam, C. F. Gilks, R. A. Wilson, M. E. Mulligan, K. S. Adams, and R. D. Arbeit. 1995. Clonal relationships among bloodstream isolates of Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 63:2409-2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ott, M., L. Bender, G. Blum, M. Schmittroth, M. Achtman, H. Tschäpe, and J. Hacker. 1991. Virulence patterns and long-range genetic mapping of extraintestinal Escherichia coli K1, K5, and K100 isolates: use of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Infect. Immun. 59:2664-2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Otto, G., M. Magnusson, M. Svensson, J. H. Braconnier, and C. Svanborg. 2001. pap genotype and P fimbrial expression in Escherichia coli causing bacteremic and nonbacteremic febrile urinary tract infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:1523-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Picard, B., P. Duriez, S. Gouriou, I. Matic, E. Denamur, and F. Taddei. 2001. Mutator natural Escherichia coli isolates have an unusual virulence phenotype. Infect. Immun. 9:9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Picard, B., J. S. Garcia, S. Gouriou, P. Duriez, N. Brahimi, E. Bingen, J. Elion, and E. Denamur. 1999. The link between phylogeny and virulence in Escherichia coli extraintestinal infection. Infect. Immun. 67:546-553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Picard, B., and P. Goullet. 1988. Correlation between electrophoretic types B1 and B2 of carboxylesterase B and host-dependent factors in Escherichia coli septicaemia. Epidemiol. Infect. 100:51-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rasko, D. A., J. A. Phillips, X. Li, and H. L. T. Mobley. 2001. Identification of DNA sequences from a second pathogenicity island of uropathogenic Escherichia coli CFT073: probes specific for uropathogenic populations. J. Infect. Dis. 184:1041-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russo, T. A., and J. R. Johnson. 2000. Proposal for a new inclusive designation for extraintestinal pathogenic isolates of Escherichia coli: ExPEC. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1753-1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schubert, S., S. Cuenca, D. Fischer, and J. Heesemann. 2000. High-pathogenicity island of Yersinia pestis in Enterobacteriaceae isolated from blood cultures and urine samples: prevalence and functional expression. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1268-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schubert, S., A. Rakin, H. Karch, E. Carniel, and J. Heesemann. 1998. Prevalence of the “high-pathogenicity island” of Yersinia species among Escherichia coli strains that are pathogenic to humans. Infect. Immun. 66:480-485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swenson, D. L., N. O. Bukanov, D. E. Berg, and R. A. Welch. 1996. Two pathogenicity islands in uropathogenic Escherichia coli J96: cosmid cloning and sample sequencing. Infect. Immun. 64:3736-3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]