Abstract

The genes nysH and nysG, encoding putative ABC-type transporter proteins, are located at the flank of the nystatin biosynthetic gene cluster in Streptomyces noursei ATCC 11455. To assess the possible roles of these genes in nystatin biosynthesis, they were inactivated by gene replacements leading to in-frame deletions. Metabolite profile analysis of the nysH and nysG deletion mutants revealed that both of them synthesized nystatin at a reduced level and produced considerable amounts of a putative nystatin analogue. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance structural analyses of the latter metabolite confirmed its identity as 10-deoxynystatin, a nystatin precursor lacking a hydroxyl group at C-10. Washing experiments demonstrated that both nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin are transported out of cells, suggesting the existence of an alternative efflux system(s) for the transport of nystatin-related metabolites. This notion was further corroborated in experiments with the ATPase inhibitor sodium o-vanadate, which affected the production of nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin in the wild-type strain and transporter mutants in a different manner. The data obtained in this study suggest that the efflux of nystatin-related polyene macrolides occurs through several transporters and that the NysH-NysG efflux system provides conditions favorable for C-10 hydroxylation.

Antibiotic-producing bacteria have developed several mechanisms for protection from the toxic actions of their endogenously synthesized antibiotics, including modification of target sites (20) or the antibiotic itself (16) as well as active efflux of antibiotic molecules (31). The latter mechanism often employs ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transport systems, which usually consist of polypeptides capable of forming channels in bacterial membranes (23). ABC transporters comprise one of the largest protein families, with members being found in a wide variety of organisms, from bacteria to humans. These proteins transport a large number of structurally diverse substrates in and out of cells, including antibiotics, inorganic acids, sugars, amino acids, proteins, polysaccharides, etc. (21). Transporters of the ABC superfamily contain both hydrophilic (ATP-hydrolyzing) and hydrophobic (membrane-spanning) domains, allowing them to couple the energy of ATP hydrolysis to molecular transport across the membrane. Typically, ABC transport systems comprise two ATP-hydrolyzing domains and two transmembrane (TM) domains, which can be located either on the same or on separate polypeptides (21). Some studies indicate that ABC efflux systems capture their substrates from within the membrane lipid bilayer and transport them out of the cell upon ATP hydrolysis (6, 22). Although the detailed mechanisms of many ABC transporter functions still remain unclear, common motifs begin to emerge due to an increasing number of structural studies on these proteins (13, 29). In general, ABC transporters act as “back-to-back” homodimers which are embedded into biological membranes through their TM domains, with their ATPase domains protruding into the cytoplasm or periplasm (36). A model for substrate transport by ABC proteins has been suggested based on studies of MDR1 and LmrA ABC transporters (39, 41). The model for exporters assumes that TM domains contain high-affinity (intracellular) and low-affinity (extracellular) substrate binding sites, with the affinity for substrate and localization alternating upon ATP hydrolysis to induce the conformational change required for such reorientation (21).

Several putative ABC transporter-encoding genes associated with antibiotic biosynthesis gene clusters have been cloned from antibiotic-producing Streptomyces bacteria. However, very few detailed studies on these systems have been reported. The ABC transporter OleB, which contains both transmembrane and ATP-binding domains, was shown to be involved in antibiotic oleandomycin resistance and secretion in Streptomyces antibioticus (33). This organism appears to contain an oleandomycin-specific glycosyltransferase, which inactivates the intracellular antibiotic through glycosylation (42). The OleB transporter, which most probably forms a homodimer in the S. antibioticus membrane, recognizes this inactive glycosylated form of oleandomycin and transports it outside the mycelium, where it is converted to an active form via the action of a specific glycosylase (34). A different ABC transport system characterized in Streptomyces rochei apparently consists of two proteins, with one representing the membrane component and another being an ATP-binding polypeptide. It has been demonstrated that this system, when overexpressed, provides a multidrug resistance phenotype in Streptomyces spp. and is therefore rather unspecific (17).

Recent genome sequencing of the model species Streptomyces coelicolor revealed the presence of at least 137 ABC transporters (4). This could have been expected, considering that streptomycetes live in soil and are constantly challenged by potentially toxic compounds. In addition, many streptomycetes produce several antibiotics that should be exported out of the cell (45). Streptomyces bacteria producing polyene macrolide antibiotics represent a special case when it comes to antibiotic resistance and efflux. Due to their specific mode of action, which involves interactions with sterols, polyene antibiotics usually have no antibacterial activity. Nevertheless, all polyene antibiotic gene clusters characterized so far encode ABC transporter systems that are presumably responsible for the efflux of these compounds from the producing bacteria (1, 7, 11, 12). For the current study, we have analyzed two ABC transporter-encoding genes, nysH and nysG, located at the border of the nystatin biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces noursei ATCC 11455. An analysis of transporter mutants revealed that they produce, in addition to nystatin, considerable amounts of its precursor, 10-deoxynystatin. This finding suggested a link between the efflux of antibiotic and its biosynthesis. An analysis of the transporter mutants' phenotypes by washing experiments and ATPase inhibitor studies confirmed the existence of an alternative efflux system in S. noursei that ensures the transport of nystatin-related compounds. It appears, however, that this system provides less favorable conditions for C-10 hydroxylation than the NysH-NysG transporter.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, phages, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains, plasmids, and phages used in this study are described in Table 1. S. noursei strains were maintained on ISP2 agar medium (Difco) and grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB; Oxoid) for DNA isolation. Escherichia coli strains were handled using standard techniques (35). Conjugation from E. coli ET12567(pUZ8002) to S. noursei and the gene replacement procedure were performed as described previously (18, 37). Nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin production was assessed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (with an instrument equipped with a diode array detector [DAD]) of dimethylformamide extracts of cultures from 500-ml shake flask fermentations in 100 ml semidefined SAO-23 medium (37) or by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analyses of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) extracts of cultures from 96-well plate fermentations. Well plate cultivation, used exclusively for vanadate studies, was performed in 96-well plates (Greiner 96-well master block; 2.4 ml per well). The media used were 0.5× TSB(G) medium (TSB [Oxoid] [18.5 g/liter] and glucose [20 g/liter]) for precultures and 0.5× SAO-23 medium (SAO-23 medium diluted 1:1 with water) (36) for the production of nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin. Each well was supplemented with 0.6 ml medium and one 3-mm glass bead. Spore suspensions (20 μl per well) of the different strains were used to inoculate preculture plates, which were then incubated at 28°C for 18 h in a well plate incubator (Infors Multitron microtiter incubator with orbital movement; amplitude, 3 mm; 800 rpm). A preculture (3.3% [vol/vol]) was used as the inoculum for the production plates, which were incubated for 96 h under the same conditions as those used for the preculture plates. Sodium o-vanadate was added to the cultures after 24 h of incubation. Antibiotics and sodium o-vanadate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, phages, and plasmids used in this study

| Strain, phage, or plasmida | Characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli | ||

| XL-1 Blue MRA(P2) | Cloning host | Stratagene |

| ET12567 | Strain for intergeneric conjugation | 30 |

| Streptomyces noursei | ||

| ATCC 11455 | Wild type, nystatin producer | ATCC |

| AHH2 | ΔnysH mutant | This work |

| AHG13 | ΔnysG mutant | This work |

| Recombinant phages | ||

| N40 | Recombinant λ phage (nystatin cluster) | 7 |

| N90 | Recombinant λ phage (nystatin cluster) | 7 |

| Recombinant plasmids | ||

| pGEM3Zf(−) | ColE1 replicon, Apr, 3.2 kb | Promega |

| pGEM11Zf(−) | ColE1 replicon, Apr, 3.2 kb | Promega |

| pSOK804 | Mobilizable integrative vector for gene expression in S. noursei | 38 |

| pSOK201 | Mobilizable suicide vector for S. noursei | 46 |

| pBlueScript-vsip | Plasmid containing vsip promoter | 40 |

| pVSI101 | vsip promoter cloned into pGEM3Zf(−) | This work |

| pNHE1 | pSOK804-based plasmid for expression of nysH | This work |

| pNGE1 | pSOK804-based plasmid for expression of nysG | This work |

| pNAP101 | nysAp promoter cloned into pGEM3Zf(−) | This work |

| pMOX101 | pSOK804-based plasmid for expression of nysL | This work |

See Materials and Methods for details on plasmid construction.

DNA manipulation and analysis of amino acid sequences.

The DNA fragments and sequences used in this study have been previously described by Brautaset et al. (7). General techniques for DNA manipulation were used as described elsewhere (35). The isolation of DNA fragments from agarose gel was done with a QIAEX kit (QIAGEN, Germany). Southern blot analysis was performed with a DIG High Prime labeling kit (Roche Biochemicals, Germany) according to the manufacturer's manual. Oligonucleotide primers were purchased from MWG Biotech (Germany). Analyses of the amino acid sequences were performed using the online programs PSORT Prediction (http://psort.nibb.ac.jp/form.html), MEME (http://meme.sdsc.edu/meme/website/meme.html), Pfam (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/Pfam/search.shtml), and MOTIF (http://motif.genome.jp/).

Construction of gene replacement plasmids. (i) Plasmid for nysG deletion.

A 1.42-kb DNA fragment designated PG12, encompassing the region upstream of nysG and some of its coding region, was amplified from the phage N40 template using primers PG1 (5′-GCAGAATTCAGGACGTTCCGCTGGCAC-3′) and PG2 (5′-GCACTGCAGAACGCGTTGAGCACGATC-3′) (underlining indicates a restriction enzyme site). A 1.43-kb DNA fragment, PG34, encompassing the 3′ end of nysG and its downstream region, was amplified from the N40 template using primers PG3 (5′-GCACTGCAGATCAACTCCTGTGCGCGC-3′) and PG4 (5′-GCCAAGCTTCCGTCTTCGAGCCGGAGAG-3′). The PG12 and PG34 PCR products were digested with the EcoRI/PstI and PstI/HindIII endonucleases, respectively, and ligated together with the 3.0-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment from pSOK201, yielding the nysG replacement vector pNGD101.

(ii) Plasmid for nysH deletion.

A 1.44-kb DNA fragment designated PH12, encompassing the region upstream of nysH and some of its coding region, was amplified from the phage N40 template using primers PH1 (5′-CGAAAGCTTGAGAACTGCTACCAGTTGG-3′) and PH2 (5′-GCACTGCAGGATCTGGACGAGTTGAAG-3′). A 1.38-kb DNA fragment, PH34, encompassing the 3′ end of nysH and its downstream region, was amplified from the N90 template using primers PH3 (5′-GCACTGCAGGATCGTGGTGCTGGACCG-3′) and PH4 (5′-GCAGAATTCGGTGCCGTCCAGGAGGATG-3′). The PH12 and PH34 PCR products were digested with the PstI/HindIII and EcoRI/PstI endonucleases, respectively, and ligated together with the 3.0-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment from pSOK201, yielding the nysH replacement vector pNHD101.

Construction of nysH, nysG, and nysL expression vectors. (i) nysG expression vector.

A 0.35-kb BamHI-PstI fragment containing the vsip promoter was ligated with the pGEM3Zf plasmid digested with the BamHI and PstI restriction enzymes. The resulting plasmid was named pVSI101. A 3.26-kb XhoII-HindIII fragment containing the promoterless nysG gene was excised from the N40 phage DNA and ligated into the pGEM7Zf vector digested with BamHI and HindIII, yielding the pNYSG1 plasmid. A 0.35-kb EcoRI-PstI vsip promoter fragment was excised from pVSI101 and ligated together with a 3.28-kb NsiI-HindIII fragment from pNYSG1 containing nysG into the pSOK804 integrative vector digested with EcoRI and HindIII. The resulting vector, pNGE1, was used for nysG expression in S. noursei.

(ii) nysH expression vector.

Two fragments, a 1.53-kb SphI-BglII fragment and a 0.39-kb BglII-MluI fragment, containing the 5′ end with a central part and the 3′ end of the nysH gene, respectively, were ligated with the pGEM7Zf vector digested with SphI and MluI, resulting in plasmid pNYSH1. The 1.98-kb SphI-NsiI fragment from pNYSH1, containing the nysH gene, was ligated together with the 0.35-kb EcoRI-SphI vsip promoter fragment from pVSI101 into the pGEM11Zf vector, resulting in the construct pNHEO. The 2.33-kb EcoRI-HindIII fragment from pNHEO, containing the vsip promoter and the nysH gene, was ligated with the pSOK804 vector digested with EcoRI and HindIII, resulting in the pNHE1 vector for expression of the nysH gene in S. noursei.

(iii) nysL expression vector.

A 197-bp DNA fragment encompassing the functional promoter of the nysA gene (8) was amplified by PCR using primers NPA1 (5′-CGACTCTAGACGCGTGGAAAACGGGTCG-3′) and NPA2 (5′-GCAGCTGCAGAAGTTGGCCTCAGGTCAC-3′). The PCR product was digested with XbaI/PstI and ligated into the pGEM3Zf(−) vector, resulting in the pNAP101 plasmid. The coding region for the complete nysL gene, with a 17-nucleotide upstream sequence encompassing a putative Shine-Dalgarno site, was amplified by PCR using primers NLE1 (5′-GCGCTGCAGTCCAGAGGAGTCCTTCCATG-3′) and NLE2 (5′-GCAGAATTCGACATCACGTCACCAGGTG-3′). The PCR product was digested with PstI and EcoRI and ligated, together with the 197-bp XbaI-PstI fragment from pNAP101, into the pGEM3Zf(−) vector. The 1.43-kb HindIII-EcoRI fragment containing nysL under control of the nysA promoter was excised from the resulting plasmid and ligated into the pSOK804 integrative vector. The plasmid, named pMOX101, was used for nysL expression in S. noursei.

LC-MS analysis and purification of the nystatin precursor 10-deoxynystatin.

LC-MS analysis was performed on an Agilent 1100 HPLC system connected to an Agilent SL ion-trap mass spectrometer using electrospray ionization in negative mode. Analytical samples were prepared by extraction of 1 ml of culture with 10 ml of dimethylformamide. A Waters NovaPak C18 column (2.1 × 150 mm) operated at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min was used for analyte separation. The mobile phase consisted of 10 mM ammonium acetate, pH 4.0, and acetonitrile (ACN). All extracts were run with a linear gradient from 30% ACN to 70% ACN in 15 min. Quantification was achieved by using experimentally determined extinction coefficients (at a 308-nm wavelength) of 700 for nystatin and 530 for 10-deoxynystatin.

The isolation of 10-deoxynystatin was performed on a preparative Agilent 1100 HPLC system configured with a passive flow split between an Agilent SL ion-trap mass spectrometer and a fraction collector. Samples for preparative isolation of 10-deoxynystatin were made by extracting a cell pellet with methanol (the pellet from a 2-ml culture was extracted with 10 ml methanol). A Waters NovaPak C18 (30 × 300 mm) preparative column was operated at 40 ml/min at 40°C, with 10 mM ammonium acetate, pH 4.0, and ACN as the mobile phase. Polyenes were eluted with a linear gradient from 35% to 55% ACN during a 25-min run. After the collection of preparative fractions, the mobile phase was exchanged with methanol using a Waters OASIS SPE instrument prior to drying under a vacuum.

Washing experiment.

After 72 h of incubation in SAO-23 medium, 1-ml culture samples were directly extracted with N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) to assess the total production of nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin. In parallel, two 1-ml culture samples were washed with 30 ml and 100 ml of SAO-23 medium to remove polyene macrolides which were either associated with the outside of the mycelia or precipitated due to low water solubility. Preliminary experiments have clearly shown that washing with 100 ml of SAO-23 medium removes most of the polyene macrolides from the samples. The washed samples were then centrifuged, and the pellets were extracted with DMF to determine the amounts of nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin remaining in the pellet. The DMF extracts were subjected to HPLC and LC-MS analyses as described above.

NMR structural analysis.

Both nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin were dissolved in DMSO-d6 at a concentration of ≈5 mM. D2O (10%) was added to improve the spectral resolution. All nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded at 400.13 MHz and 25°C on a Dpx 400 Bruker Avance spectrometer. One-dimensional spectra were acquired using 16,000 data points, a 2,600-Hz spectral width, a 30° pulse, a pulse recycling time of 7.8 s, and 64 to 256 scans. Two-dimensional homonuclear correlated COSY45 spectra were acquired using a 1,024-by-256 data matrix and were zero-filled in the F1 direction. The spectral width was 2,600 Hz in both directions. A sine-bell window function was used prior to Fourier transformation. Sixteen scans were recorded for each t1 value, with a delay of 1.35 s between scans. Chemical shifts are quoted relative to the chemical shifts of DMSO-d6 at 2.49 ppm.

RESULTS

Nystatin biosynthetic gene cluster encodes two putative ABC transporters.

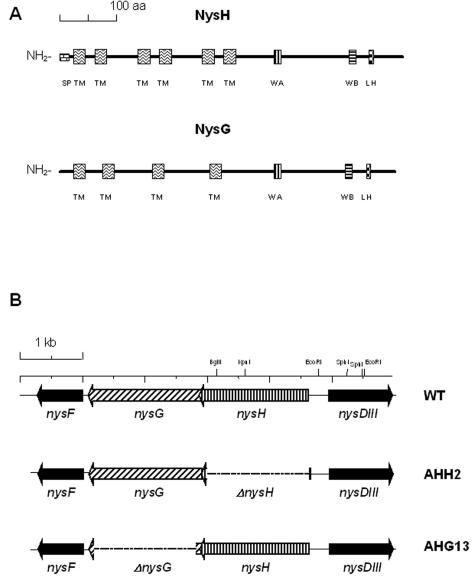

Two genes, nysH and nysG, encoding putative ABC-type transporter proteins, are located within the nystatin biosynthetic gene cluster in S. noursei ATCC 11455 (7). The 3′ end of the nysH gene overlaps the 5′ end of nysG by 23 nucleotides, suggesting that these genes may be translationally coupled. An in silico analysis of the deduced 584-amino-acid (aa) NysH protein predicted a distinct 18-aa signal sequence at its N terminus, which might assist in targeting of this polypeptide to the membrane (Fig. 1A). Six putative membrane-spanning regions were identified within the N-terminal portion of NysH. The C terminus of the deduced nysH product apparently represents the ATP-hydrolyzing domain, as it contains Walker A and B motifs as well as a Linton-Higgins motif typical of ATPases (28, 44). NysH shows high degrees of identity (75 to 84%) to the putative ABC transporters AmphH and PimA encoded by the polyene antibiotic amphotericin and pimaricin biosynthetic gene clusters in Streptomyces nodosus and Streptomyces natalensis, respectively (1, 11), and to a putative ABC transporter from Streptomyces avermitilis (BAC73393). Interestingly, the next best matches in the databases (62 to 67% identity) include ABC transporters from nonstreptomycete bacteria such as Corynebacterium glutamicum (25), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (NCBI Microbial Genomes Annotation Project), Mycobacterium leprae (14), Listeria monocytogenes (19), and Clostridium acetobutylicum (32).

FIG. 1.

ABC transporter system encoded by the nysG and nysH genes in S. noursei. (A) Predicted structural features of the NysH and NysG proteins. SP, signal peptide; TM, transmembrane helix; WA, Walker A motif; WB, Walker B motif; LH, Linton-Higgins motif. (B) Genotypes of the nysH and nysG mutants compared to the wild-type (WT) strain.

The deduced product of nysG is a 605-aa polypeptide with no apparent signal sequence. Like the case for NysH, membrane-spanning regions were identified within the N-terminal part of NysG, although only four of those gave a significantly high score upon in silico analysis. The C-terminal part of NysG presumably has the same function as its counterpart in NysH, since similar features typical of ATP-hydrolyzing domains were found in the former polypeptide (Fig. 1A). A database search with the NysG aa sequence revealed its high degrees of identity (56 to 79%) to the putative ABC transporters AmphG and PimB (1, 11). As in the case of NysH, the next best matches for NysG in the databases were represented by ABC transporters from nonstreptomycete bacteria.

nysH and nysG deletion mutants produce enhanced levels of a 910-Da nystatin analogue.

In order to test whether the NysH and NysG proteins were involved in the biosynthesis of nystatin, the corresponding genes were inactivated in S. noursei via in-frame deletions. The gene replacement vectors pNGD101 and pNHD101, for deletion of nysG and nysH, respectively, were constructed (see Materials and Methods) and introduced into S. noursei by conjugation. After several passages on nonselective medium, colonies were screened for the second crossover event by PCR, and several mutants with expected deletions within nysH and nysG were identified. The genotypes of the ΔnysH and ΔnysG mutants, designated AHH2 and AHG13, respectively, were confirmed by both PCR and Southern blot analysis (data not shown).

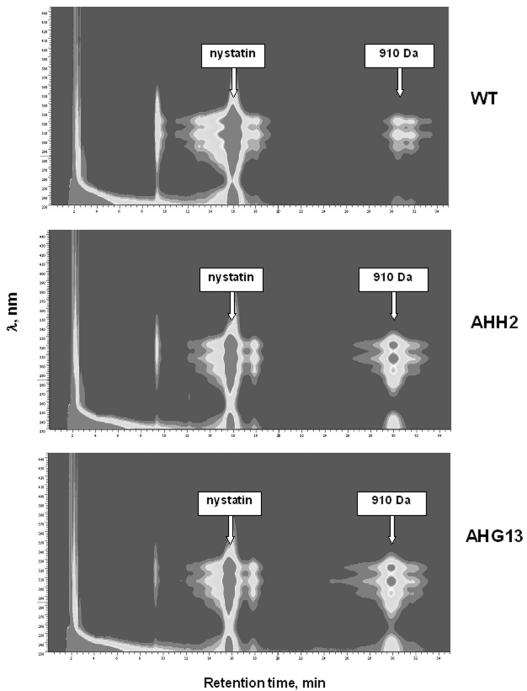

Both the AHH2 and AHG13 mutants were tested for nystatin biosynthesis along with the wild-type S. noursei. Analyses of the culture extracts showed that the level of nystatin biosynthesis is significantly reduced in both mutants (by ca. 35%) compared to that in the wild type. Analyses of culture extracts from the S. noursei ATCC 11455, AHH2, and AHG13 strains using DAD-HPLC and LC-MS revealed excessive production of a 910-Da nystatin analogue by the mutants compared to that by the wild-type strain (Fig. 2). The 910-Da compound displayed a UV spectrum typical for tetraene macrolides, showing absorption peaks at 292 nm, 308 nm, and 320 nm. The same polyene macrolide compound (judging by its molecular weight, UV spectrum, and retention time during HPLC) was also present in the culture extract of wild-type S. noursei, albeit in a much lesser quantity.

FIG. 2.

DAD-HPLC isoplots of culture extracts from S. noursei ATCC 11455 (WT) and transporter mutants. Peaks for nystatin and a 910-Da nystatin analogue are indicated.

To confirm that mutations in the AHH2 and AHG13 strains had no polar effects, plasmids pNHE1 and pNGE1, expressing nysH and nysG, respectively, from the vsip promoter (41), were constructed. Complementation experiments were carried out, and strains AHH2(pNHE1), AHG13(pNHE1), AHH2(pNGE1), and AHG13(pNGE1) were tested for the production of nystatin and the 910-Da putative nystatin analogue mentioned above. Introduction of the nysH and nysG genes into the corresponding mutants resulted in an almost complete restoration of nystatin biosynthesis and abrogation of the accumulation of the 910-Da compound (data not shown). No cross-complementation was observed in these experiments, suggesting that both NysH and NysG are required for full functionality of this putative transporter system.

The 910-Da nystatin analogue overproduced by the nysH and nysG deletion mutants is identified as 10-deoxynystatin.

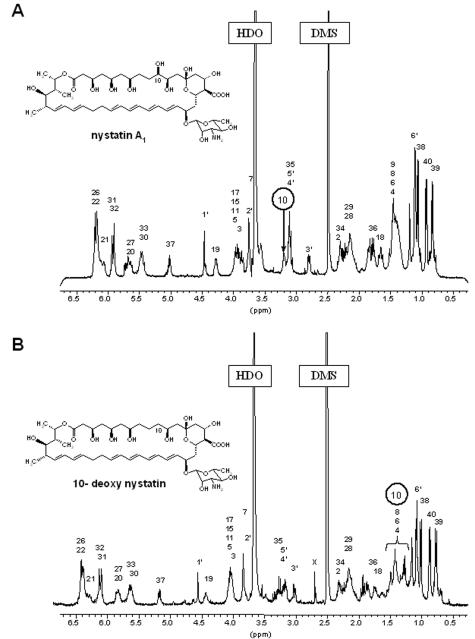

The 910-Da size of the nystatin analogue overproduced by the ΔnysH and ΔnysG mutants correlated well with the molecular mass of a putative nystatin precursor lacking one oxygen atom. The most plausible candidate for such a compound would be 10-deoxynystatin, the nystatin precursor lacking a hydroxyl group at C-10. We have previously identified the 910-Da polyene macrolide produced by wild-type S. noursei and suggested that it represents 10-deoxynystatin (10). However, we have not confirmed this suggestion with NMR data. To establish the identity of the 910-Da compound in question, it was purified and subjected to NMR analyses.

The 1H NMR spectra of nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin shown in Fig. 3 look quite similar, except that the resonance of H-10 has moved from 3.2 ppm in nystatin to around 1.5 ppm in 10-deoxynystatin. The C-10 hydroxylation implies that the protons at C-10 resonated in the methylene region around 1.5 ppm. The proton chemical shift assignments shown in Fig. 3 are based on two-dimensional spectra. Comparisons of the chemical shifts for nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin show remarkable similarities all over the molecules, except for H-10, and those for nystatin match well with published data (3, 9, 26). Both the olefinic (H-19 to H-33) and the methyl (H-6′ and H-38 to H-40) regions show identical patterns in the spectra for the two molecules. There are small chemical shift differences in the polyol and methylene regions and for the ring protons of the d-mycosamine residue. The latter might be due to some small conformational changes and/or hydrogen bonding effects imposed by the hydroxyl group at C-10.

FIG. 3.

1H NMR (400 MHz) spectra of DMSO-d6 solutions (5 mM) at 25°C of nystatin showing the H-10 proton at 3.2 ppm (A) and of 10-deoxynystatin showing the H-10 proton at 1.4 to 1.6 ppm (B). An impurity in the 10-deoxynystatin sample is indicated by an “X” in panel B.

Expression of an additional copy of nysL affects production of both nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin in ΔnysH and ΔnysG mutants.

It has been previously suggested that NysL, one of the P450 monooxygenases encoded by the nystatin biosynthetic gene cluster, may be responsible for C-10 hydroxylation of the antibiotic molecule (7). We reasoned that additional expression of NysL in the AHH2 and AHG13 mutants might alleviate the effect of the mutations leading to the accumulation of 10-deoxynystatin. An integrative vector, pMOX101, carrying the nysL gene under the control of the nysAp promoter (see Materials and Methods), was constructed and introduced into the transporter mutants. An analysis of the metabolites produced by the AHH2(pMOX101) and AHG13(pMOX101) strains demonstrated a ca. 15% increase in the nystatin volumetric yield with a simultaneous reduction (ca. 30%) in the amount of 10-deoxynystatin (data not shown). No effect on nystatin production was observed upon introduction of the pMOX101 plasmid into the wild-type strain of S. noursei. These data imply that an increase in the amount of the C-10 hydroxylase NysL leads to the conversion of at least part of the 10-deoxynystatin accumulated in the mutants to the final product.

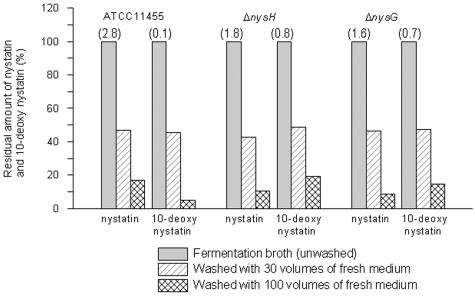

ΔnysH and ΔnysG mutants efficiently transport both nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin out of cells.

The metabolite profile analysis showed an enhanced production of 10-deoxynystatin by the ΔnysH and ΔnysG mutants, suggesting that C-10 hydroxylation is negatively affected in these strains. However, if the NysH-NysG transporter constitutes a unique system for nystatin efflux and if C-10 hydroxylation is solely dependent on it, one could expect the production of only 10-deoxynystatin by the transporter mutants. This was apparently not the case, since a significant amount of nystatin was still produced by AHH2 and AHG13, although the nystatin yield on the basis of glucose was lower than that in the wild-type strain. To assess the efflux of nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin, their levels were quantitatively analyzed in cell pellets of the wild-type strain and the transporter mutants before and after washing with an excess of fermentation medium (see Materials and Methods). The washing experiment was designed to remove nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin transported out of the cells from the culture samples. Previous observations (H. Sletta, unpublished data) have shown that nystatin and related metabolites produced by wild-type S. noursei are found in liquid cultures both as precipitated material and associated with the mycelium. The data from these experiments, presented in Fig. 4, demonstrate that for both the wild-type strain and the transporter mutants, most of the nystatin is transported out of the cells, since it can be efficiently removed by washing with fermentation medium. Also, a major portion of 10-deoxynystatin was apparently expelled from the cells of the ΔnysH and ΔnysG mutants and could be removed by washing. These results strongly argue for the existence of an alternative transporter system(s) in S. noursei that can ensure the efflux of nystatin-related metabolites from this bacterium (see Discussion).

FIG. 4.

Results of washing experiments confirming the efflux of both nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin from the S. noursei wild-type strain and transporter mutants. Numbers above the bars reflect the actual amounts (g/liter) of nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin in the fermentation broth prior to washing (averages of two experiments).

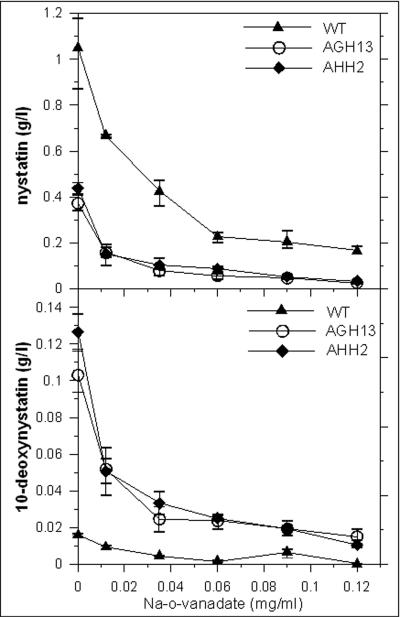

ATPase inhibitor sodium o-vanadate differentially affects the production of polyene macrolides in the wild-type strain and transporter mutants.

For many bacteria, the inactivation of ABC transporter genes leads to an increase in the sensitivity of the mutants to various antibiotics (27). We compared the resistance of wild-type S. noursei with that of the AHH2 and AHG13 mutants to erythromycin, tylosin, streptomycin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, novobiocin, and neomycin. No differences in the levels of resistance to these antibiotics were revealed (data not shown), confirming that the NysH-NysG transporter system is not involved in efflux of these antibiotics.

Next, the effect of sodium o-vanadate on the production of nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin by the S. noursei wild-type strain and transporter mutants was studied. Sodium o-vanadate is a potent inhibitor of ATPase activity (15), which is the relevant property of many ABC-type transporters. In this experiment, cultures were initially grown for 24 h without the inhibitor, and then different amounts of sodium o-vanadate were added to the fermentation medium. The production of polyene macrolides in the cultures was monitored over the next 72 h, using LC-MS. It should be noted that no visible effect on the growth characteristics of cultures was observed for sodium o-vanadate concentrations of up to 0.036 mg/ml.

As shown in Fig. 5 (top panel), the addition of sodium o-vanadate inhibited the production of nystatin in both the wild-type strain and the transporter mutants in a concentration-dependent manner. However, a significant difference between the wild-type strain and the transporter mutants in the response to the inhibitor was detected at sodium o-vanadate concentrations between 0.01 and 0.06 mg/ml. Under these conditions, the inhibition of nystatin production was more pronounced for the transporter mutants than for the wild-type strain (Fig. 5, top panel). The addition of vanadate at a concentration of 0.01 mg/ml decreased nystatin production by the wild-type strain by ca. 38%, while causing a ca. 63% drop in nystatin production by the transporter mutants. At the same time, there was a decrease of ca. 55% in the production of 10-deoxynystatin under these conditions for the transporter mutants. The drop in 10-deoxynystatin production by the wild-type strain could not be measured reliably because of the very low yield of the compound. These data were consistent with the assumption that there exists an alternative to the NysH-NysG transporter system in S. noursei to ensure the efflux of nystatin-related metabolites and that this system is more sensitive to inhibition by vanadate.

FIG. 5.

Effect of sodium o-vanadate on biosynthesis of nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin by S. noursei wild-type strain and ΔnysH (AHH2) and ΔnysG (AHG13) mutants. Average data from three parallel experiments are presented.

DISCUSSION

ABC transporter systems play an important role in the active transport of structurally diverse compounds from Streptomyces bacteria. Genes encoding ABC transporters have been identified in several clusters governing the biosynthesis of macrolide antibiotics, including those for polyene macrolides (2, 24, 31). Due to their quite specific mode of action related to their affinity to sterols (5), the latter antibiotics generally do not have any detectable antibacterial activity and thus should not represent a threat to the producing organism. On the other hand, polyene macrolides are poorly soluble in water, and their accumulation inside the cell may be harmful, suggesting that active efflux of these compounds should be ensured. It has been assumed that ABC transporters encoded by the genes located within the polyene macrolide biosynthetic gene clusters are responsible for such efflux (2).

The genes nysH and nysG encoding a putative nystatin efflux system seem to be translationally coupled, which is logical considering that the coordinated expression of these two genes would ensure the proper assembly of a fully functional transporter system. Both NysH and NysG apparently belong to the type III ABC transporters, which are characterized by having both TM and ATPase domains on one polypeptide (31). Although quite similar in their domain organization, NysH and NysG seem to possess different numbers of transmembrane helices (Fig. 1A). In addition, NysH was predicted to contain a signal peptide sequence whose obvious function would be the targeting of the protein to the membrane immediately after its synthesis.

Inactivation of the NysH-NysG system in S. noursei led to an accumulation of the nystatin precursor 10-deoxynystatin in the mutants. Interestingly, NMR studies that were carried out to confirm the structural identity of 10-deoxynystatin suggested conformational changes that seem to affect the mycosamine moiety. Since the β-glycosidic bond linking mycosamine to the macrolactone ring is presumed to be flexible and since both the mycosamine moiety and the C-10 hydroxyl on the nystatin molecule are located above the plane of the ring (43), their interaction via hydrogen bond formation seems plausible. The absence of such an interaction in 10-deoxynystatin could probably explain an increase in the chemical shift observed for the proton H3′ on the mycosamine moiety of this compound.

The polyene macrolide metabolite profiles of the ΔnysH and ΔnysG mutants were very similar (Fig. 2), and no cross-complementation could be observed, strongly suggesting that the products of both genes are important for the full functionality of the ABC transporter. This was confirmed by gene disruption using an internal DNA fragment of nysH which would also have a polar effect on nysG. The resulting mutant was shown to have the same phenotype as the ΔnysH and ΔnysG mutants (unpublished data). This experiment further confirmed that NysH and NysG are part of the same transporter and suggested that the NysH-NysG system is not the only one in S. noursei that can transport nystatin and related metabolites out of the producing cells. The washing experiments clearly demonstrated that most of both nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin is transported out of the cells, confirming the existence of an alternative to the NysH-NysG efflux system for nystatin-related polyene macrolides.

The phenotypes of the nysH and nysG mutants clearly show the link between nystatin transport and C-10 hydroxylation, as exemplified by the fact that the presumed overexpression of the C-10 hydroxylase NysL partially alleviates the overproduction of 10-deoxynystatin by the transporter mutants and increases the nystatin volumetric yield. Most probably, the rate of nystatin efflux by the NysH-NysG transporter and the hydroxylation of 10-deoxynystatin by NysL are balanced, providing for efficient nystatin biosynthesis and transport in wild-type S. noursei. Upon inactivation of NysH or NysG, nystatin-related metabolites are transported by an alternative efflux pump, which functions out of balance with the NysL hydroxylase, thus leading to subefficient conversion of 10-deoxynystatin to nystatin and overproduction of the former metabolite.

The existence of an alternative to the NysH-NysG transporter system for polyene macrolides in S. noursei is supported by the data from vanadate inhibition experiments. We have assumed, based on the phenotypes of the transporter mutants, that the production of nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin reflects to a certain extent the process of these metabolites' efflux. The significantly more efficient inhibition of nystatin and 10-deoxynystatin production by vanadate in the ΔnysH and ΔnysG mutants than in the wild-type strain strongly suggests that the alternative system for the efflux of nystatin-related metabolites in S. noursei is more sensitive to vanadate than the NysH-NysG system. Consequently, such an alternative efflux system is most likely represented by an ABC transporter. The strong inhibition of nystatin production in S. noursei by vanadate can probably not be explained solely by inhibition of the transporter systems. The negative effect of vanadate on nystatin biosynthesis may also be attributed to an inhibition of the ATPase activity necessary for central metabolism, although we have not observed changes in the growth pattern at the lowest vanadate concentrations used. More likely, vanadate inhibits the DNA binding activity of the NysRI and NysRIII proteins, which are regulators of nystatin biosynthesis containing distinct ATPase domains (38).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to F. Gullion for help with the purification of 10-deoxynystatin and to J. Anne for providing the pBlueScript-vsip plasmid.

This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aparicio, J. F., R. Fouces, M. V. Mendes, N. Olivera, and J. F. Martín. 2000. A complex multienzyme system encoded by five polyketide synthase genes is involved in the biosynthesis of the 26-membered polyene macrolide pimaricin in Streptomyces natalensis. Chem. Biol. 7:895-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aparicio, J. F., P. Caffrey, J. A. Gil, and S. B. Zotchev. 2003. Polyene antibiotic biosynthesis gene clusters. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 61:179-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aszalos, A., A. Bax, N. Burlinson, P. Roller, and C. McNeal. 1985. Physico-chemical and microbiological comparison of nystatin, amphotericin A and amphotericin B, and structure of amphotericin A. J. Antibiot. 38:1699-1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentley, S. D., K. F. Chater, A. M. Cerdeno-Tarraga, G. L. Challis, N. R. Thomson, K. D. James, D. E. Harris, M. A. Quail, H. Kieser, D. Harper, A. Bateman, S. Brown, G. Chandra, C. W. Chen, M. Collins, A. Cronin, A. Fraser, A. Goble, J. Hidalgo, T. Hornsby, S. Howarth, C. H. Huang, T. Kieser, L. Larke, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, S. O'Neil, E. Rabbinowitsch, M. A. Rajandream, K. Rutherford, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, D. Saunders, S. Sharp, R. Squares, S. Squares, K. Taylor, T. Warren, A. Wietzorrek, J. Woodward, B. G. Barrell, J. Parkhill, and D. A. Hopwood. 2002. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature 417:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolard, J. 1986. How do the polyene macrolide antibiotics affect the cellular membrane properties? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 864:257-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolhuis, H., H. W. van Veen, J. R. Brands, M. Putman, B. Poolman, A. J. Driessen, and W. N. Konings. 1996. Energetics and mechanism of drug transport mediated by the lactococcal multidrug transporter LmrP. J. Biol. Chem. 271:24123-24128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brautaset, T., O. N. Sekurova, H. Sletta, T. E. Ellingsen, A. R. Strøm, S. Valla, and S. B. Zotchev. 2000. Biosynthesis of the polyene antifungal antibiotic nystatin in Streptomyces noursei ATCC 11455: analysis of the gene cluster and deduction of the biosynthetic pathway. Chem. Biol. 7:395-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brautaset, T., S. E. F. Borgos, H. Sletta, T. E. Ellingsen, and S. B. Zotchev. 2003. Site-specific mutagenesis and domain substitutions in the loading module of the nystatin polyketide synthase, and their effects on nystatin biosynthesis in Streptomyces noursei. J. Biol. Chem. 278:14913-14919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown, J. M., A. E. Derome, and S. J. Kimber. 1985. Association of alkali metal salts with polyene macrolides in methanol solution. Tetrahedron Lett. 26:253-256. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruheim, P., S. E. Borgos, P. Tsan, H. Sletta, T. E. Ellingsen, J. M. Lancelin, and S. B. Zotchev. 2004. Chemical diversity of polyene macrolides produced by Streptomyces noursei ATCC 11455 and recombinant strain ERD44 with genetically altered polyketide synthase NysC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4120-4129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caffrey, P., S. Lynch, E. Flood, S. Finnan, and M. Oliynyk. 2001. Amphotericin biosynthesis in Streptomyces nodosus: deductions from analysis of polyketide synthase and late genes. Chem. Biol. 8:713-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campelo, A. B., and J. A. Gil. 2002. The candicidin gene cluster from Streptomyces griseus IMRU 3570. Microbiology 148:51-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang, G., and C. B. Roth. 2001. Structure of MsbA from E. coli: a homolog of the multidrug resistance ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporters. Science 293:1793-1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cole, S. T., K. Eiglmeier, J. Parkhill, K. D. James, N. R. Thomson, P. R. Wheeler, N. Honore, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, K. Mungall, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. M. Davies, K. Devlin, S. Duthoy, T. Feltwell, A. Fraser, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, C. Lacroix, J. Maclean, S. Moule, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, M. A. Quail, M. A. Rajandream, K. M. Rutherford, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, S. Simon, M. Simmonds, J. Skelton, R. Squares, S. Squares, K. Stevens, K. Taylor, S. Whitehead, J. R. Woodward, and B. G. Barrell. 2001. Massive gene decay in the leprosy bacillus. Nature 409:1007-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dafnis, E., and S. Sabatini. 1994. Biochemistry and pathophysiology of vanadium. Nephron 67:133-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies, J. E., and R. E. Benveniste. 1974. Enzymes that inactivate antibiotics in transit to their targets. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 235:130-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandez-Moreno, M. A., L. Carbo, T. Cuesta, C. Vallin, and F. Malpartida. 1998. A silent ABC transporter isolated from Streptomyces rochei F20 induces multidrug resistance. J. Bacteriol. 180:4017-4023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flett, F., V. Mersinias, and C. P. Smith. 1997. High efficiency intergeneric conjugal transfer of plasmid DNA from Escherichia coli to methyl DNA-restricting streptomycetes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 155:223-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glaser, P., L. Frangeul, C. Buchrieser, C. Rusniok, A. Amend, F. Baquero, P. Berche, H. Bloecker, P. Brandt, T. Chakraborty, A. Charbit, F. Chetouani, E. Couve, A. de Daruvar, P. Dehoux, E. Domann, G. Dominguez-Bernal, E. Duchaud, L. Durant, O. Dussurget, K. D. Entian, H. Fsihi, F. G. Portillo, P. Garrido, L. Gautier, W. Goebel, N. Gomez-Lopez, T. Hain, J. Hauf, D. Jackson, L. M. Jones, U. Kaerst, J. Kreft, M. Kuhn, F. Kunst, G. Kurapkat, E. Madueno, A. Maitournam, J. M. Vicente, E. Ng, H. Nedjari, G. Nordsiek, S. Novella, B. de Pablos, J. C. Perez-Diaz, R. Purcell, B. Remmel, M. Rose, T. Schlueter, N. Simoes, A. Tierrez, J. A. Vazquez-Boland, H. Voss, J. Wehland, and P. Cossart. 2001. Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science 294:849-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham, M. Y., and B. Weisblum. 1979. 23S ribosomal ribonucleic acid of macrolide-producing streptomycetes contains methylated adenine. J. Bacteriol. 137:1464-1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins, C. F. 2001. ABC transporters: physiology, structure and mechanism—an overview. Res. Microbiol. 152:205-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Homolya, L., Z. Hollo, U. A. Germann, I. Pastan, M. M. Gottesman, and B. Sarkadi. 1993. Fluorescent cellular indicators are extruded by the multidrug resistance protein. J. Biol. Chem. 268:21493-21496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyde, S. C., P. Emsley, M. J. Hartshorn, M. M. Mimmack, U. Gileadi, S. R. Pearce, M. P. Gallagher, D. R. Gill, R. E. Hubbard, and C. F. Higgins. 1990. Structural model of ATP-binding proteins associated with cystic fibrosis, multidrug resistance and bacterial transport. Nature 346:362-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikeda, H., J. Ishikawa, A. Hanamoto, M. Shinose, H. Kikuchi, T. Shiba, Y. Sakaki, M. Hattori, and S. Omura. 2003. Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of the industrial microorganism Streptomyces avermitilis. Nat. Biotechnol. 21:526-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krubasik, P., M. Kobayashi, and G. Sandmann. 2001. Expression and functional analysis of a gene cluster involved in the synthesis of decaprenoxanthin reveals the mechanisms for C50 carotenoid formation. Eur. J. Biochem. 268:3702-3708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lancelin, J. M., and J. M. Beau. 1989. Complete stereostructure of nystatin A1: a proton NMR study. Tetrahedron Lett. 30:4521-4524. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, X. Z., and H. Nikaido. 2004. Efflux-mediated drug resistance in bacteria. Drugs 64:159-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linton, K. J., and C. F. Higgins. 1998. The Escherichia coli ATP-binding cassette (ABC) proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 28:5-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Locher, K. P., A. T. Lee, and D. C. Rees. 2002. The E. coli BtuCD structure: a framework for ABC transporter architecture and mechanism. Science 296:1091-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacNeil, D. J., K. M. Gewain, C. L. Ruby, G. Dezeny, P. H. Gibbons, and T. MacNeil. 1992. Analysis of Streptomyces avermitilis genes required for avermectin biosynthesis utilizing a novel integration vector. Gene 111:61-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mendez, C., and J. A. Salas. 2001. The role of ABC transporters in antibiotic-producing organisms: drug secretion and resistance mechanisms. Res. Microbiol. 152:341-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nolling, J., G. Breton, M. V. Omelchenko, K. S. Makarova, Q. Zeng, R. Gibson, H. M. Lee, J. Dubois, D. Qiu, J. Hitti, Y. I. Wolf, R. L. Tatusov, F. Sabathe, L. Doucette-Stamm, P. Soucaille, M. J. Daly, G. N. Bennett, E. V. Koonin, and D. R. Smith. 2001. Genome sequence and comparative analysis of the solvent-producing bacterium Clostridium acetobutylicum. J. Bacteriol. 183:4823-4838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olano, C., A. M. Rodriguez, C. Mendez, and J. A. Salas. 1995. A second ABC transporter is involved in oleandomycin resistance and its secretion by Streptomyces antibioticus. Mol. Microbiol. 16:333-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salas, J. A., C. Hernandez, C. Mendez, C. Olano, L. M. Quiros, A. M. Rodriguez, and C. Vilches. 1994. Intracellular glycosylation and active efflux as mechanisms for resistance to oleandomycin in Streptomyces antibioticus, the producer organism. Microbiologia 10:37-48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 36.Schmitt, L., and R. Tampe. 2002. Structure and mechanism of ABC transporters. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12:754-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sekurova, O., H. Sletta, T. E. Ellingsen, S. Valla, and S. B. Zotchev. 1999. Molecular cloning and analysis of a pleiotropic regulatory gene locus from the nystatin producer Streptomyces noursei ATCC 11455. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 177:297-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sekurova, O. N., T. Brautaset, H. Sletta, S. E. F. Borgos, Ø. M. Jakobsen, T. E. Ellingsen, A. R. Strøm, S. Valla, and S. B. Zotchev. 2004. In vivo analysis of the regulatory genes in the nystatin biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces noursei ATCC 11455 reveals their differential control over antibiotic biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 186:1345-1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Senior, A. E. 1998. Catalytic mechanism of P-glycoprotein. Acta Physiol. Scand. 643(Suppl.):213-218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Mellaert, L., E. Lammertyn, S. Schacht, P. Proost, J. Van Damme, B. Wroblowski, J. Anne, T. Scarcez, E. Sablon, J. Raeymaeckers, and A. Van Broekhoven. 1998. Molecular characterization of a novel subtilisin inhibitor protein produced by Streptomyces venezuelae CBS762.70. DNA Seq. 9:19-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Veen, H. W., A. Margolles, M. Muller, C. F. Higgins, and W. N. Konings. 2000. The homodimeric ATP-binding cassette transporter LmrA mediates multidrug transport by an alternating two-site (two-cylinder engine) mechanism. EMBO J. 19:2503-2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vilches, C., C. Hernandez, C. Mendez, and J. A. Salas. 1992. Role of glycosylation and deglycosylation in biosynthesis of and resistance to oleandomycin in the producer organism Streptomyces antibioticus. J. Bacteriol. 174:161-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Volpon, L., and J. M. Lancelin. 2002. Solution NMR structure of five representative glycosylated polyene macrolide antibiotics with a sterol-dependent antifungal activity. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:4533-4541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker, J. E., M. Saraste, M. J. Runswick, and N. J. Gay. 1982. Distantly related sequences in the alpha- and beta-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1:945-951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watve, M. G., R. Tickoo, M. M. Jog, and B. D. Bhole. 2001. How many antibiotics are produced by the genus Streptomyces? Arch. Microbiol. 176:386-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zotchev, S. B., K. Haugan, O. Sekurova, H. Sletta, T. E. Ellingsen, and S. Valla. 2000. Identification of a gene cluster for antibacterial polyketide-derived antibiotic biosynthesis in the nystatin producer Streptomyces noursei ATCC 11455. Microbiology 146:611-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]