Abstract

The 51 human adenovirus serotypes are divided into six species (A to F). Adenovirus serotypes from all species except species B utilize the coxsackie-adenovirus receptor for attachment to host cells in vitro. Species B adenoviruses primarily cause ocular and respiratory tract infections, but certain serotypes are also associated with renal disease. We have previously demonstrated that adenovirus type 11 (species B) uses CD46 (membrane cofactor protein) as a cellular receptor instead of the coxsackie-adenovirus receptor (A. Segerman et al., J. Virol. 77:9183-9191, 2003). In the present study, we found that transfection with human CD46 cDNA rendered poorly permissive Chinese hamster ovary cells more permissive to infection by all species B adenovirus serotypes except adenovirus types 3 and 7. Moreover, rabbit antiserum against human CD46 blocked or efficiently inhibited all species B serotypes except adenovirus types 3 and 7 from infecting human A549 cells. We also sequenced the gene encoding the fiber protein of adenovirus type 50 (species B) and compared it with the corresponding amino acid sequences from selected serotypes, including all other serotypes of species B. From the results obtained, we conclude that CD46 is a major cellular receptor on A549 cells for all species B adenoviruses except types 3 and 7.

The adenovirus (Ad) family contains 51 human serotypes, which are divided into six species (A to F [7, 43]). Human adenoviruses cause infections of the respiratory tract, eyes, urinary tract, intestine, or lymphoid tissue (41). The virion is mainly built up of three proteins: the hexon, the penton base, and the fiber. Hexon protein, made up of three identical polypeptides, is the main constituent of the particle. At each of the 12 vertices, there is a pentameric penton base protein which is associated with a trimeric fiber protein (36). Together, these two proteins form the penton base. The fiber protein has been shown to mediate attachment to host cells in vitro, whereas the penton base facilitates the subsequent internalization step (45). Adenovirus type 2 (Ad2) and Ad5 were initially demonstrated to use CAR (coxsackie-adenovirus receptor) as a cellular receptor (8, 39). Subsequently, selected adenoviruses from all species except species B were shown to interact with soluble CAR in vitro (30). Three additional proteins have been found to mediate attachment and entry of Ad5: MHC-1 α2 (23), VCAM-1 (13), and heparan sulfate (15, 16). However, their role as cellular receptors in relation to CAR has not yet been fully established. Moreover, three serotypes of species D (i.e., Ad8, Ad19, and Ad37), which are the main causative agents of epidemic keratoconjunctivitis, are known to use sialic acid as a functional cellular receptor (2-6, 11, 12).

Species B adenoviruses are further subdivided into subspecies B1 (Ad3, Ad7, Ad16, Ad21, and Ad50) and B2 (Ad11, Ad14, Ad34, and Ad35) (7). Most species B adenoviruses cause respiratory and/or ocular infections (41). In addition, three species B2 viruses (Ad11, Ad34, and Ad35) have been shown to cause renal infections and are closely associated with fatal outcome in immunocompromised patients (26, 27). Ad3 and Ad7 cause disease in humans more frequently than other species B serotypes, and the seroprevalence of these two viruses is higher than for other species B serotypes (40). Several years ago, it was demonstrated that Ad3 virions interact with a 100-kDa and a 130-kDa membrane protein from HeLa cells (19). The Ad3 fiber did not interact with the 100-kDa protein but interacted with the 130-kDa protein in a divalent-cation-dependent manner. Since then, no other successful attempts to characterize cellular receptors for species B adenoviruses had been made until recently, when it was demonstrated that the binding abilities of Ad3 and Ad7 (B1), but not of Ad11 or Ad35 (B2), were dependent on divalent cations and sensitive to pretrypsination of host cells (34). Moreover, Ad11 and Ad35 blocked binding of Ad3 and Ad7 to host cells, but Ad3 and Ad7 were unable to block binding of Ad11 and Ad35. Based on these findings, the existence of a cellular receptor common to all species B viruses was suggested (sBAR, or species B adenovirus receptor). In addition, species B2 adenoviruses were suggested to interact with an additional receptor, designated sB2AR (species B2 adenovirus receptor) (34). Subsequently, we identified CD46 as a functional cellular receptor for Ad11 and hypothesized that this receptor was identical to sB2AR (35).

The above studies were partially confirmed by Gaggar et al., who demonstrated that several species B2 adenoviruses (Ad11, Ad14, and Ad35) attached to CD46-expressing CHO cells (CHO-CD46) more efficiently than to CHO cells that could not express CD46 (21). Moreover, Ad16, Ad21, and Ad50 from subspecies B1 also attached more efficiently to CHO-CD46 cells than to CD46-negative CHO cells. Based on these findings, it was assumed that CD46 is a cellular receptor for species B adenoviruses, despite the fact that (i) one serotype (Ad3) did not bind to CHO-CD46 cells more efficiently than to CHO cells not expressing CD46 and that (ii) two species B serotypes (Ad7 and Ad34) were not investigated at all. In contrast to Gaggar and coworkers, Sirena et al. recently suggested that Ad3 uses CD46 as a cellular receptor (38), and in another paper it was recently suggested that Ad3 uses CD80 and CD86 as cellular attachment receptors (37). Based on the conflicting and somewhat incongruous results published previously regarding the identity of the receptors used by species B adenoviruses, this study, which is the first to involve all serotypes of species B, was undertaken in order to specifically identify which of the species B serotypes use CD46 as a functional cellular receptor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, and antibodies. (i) Cells.

Human respiratory epithelial A549 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), HEPES, and penicillin-streptomycin (all from Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were cultured in Ham's F-12 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10% FCS, HEPES, and penicillin-streptomycin (all from Sigma). CHO cells expressing human membrane cofactor protein (CD46) isoform BC1 have been described elsewhere (28).

(ii) Viruses.

Ad31 (strain 1315/63, species A); Ad3 (GB, B1); Ad7 (Gomen, B1); Ad16 (CH79, B1); Ad21 (1645, B1); Ad50 (Wan, B1); Ad11 (Slobitski, B2); Ad14 (DeWitt, B2); Ad34 (Compton, B2); Ad35 (Holden, B2); Ad5 (Ad75, C); Ad37 (1477, D); Ad4 (RI-67, E); and Ad41 (Tak, F) were propagated in A549 cells (Hep2 in the case of Ad41) and purified as described elsewhere (17). Since adenovirus strains can easily be cross-contaminated via cell culture, the correct identities of all virion preparations were established after restriction enzyme cleavage of purified viral DNA (data not shown) by comparison with electrophoretic patterns described previously (1, 18).

(iii) Antibodies.

The rabbit polyclonal antisera against human CD46 have been described elsewhere (28). Antisera against purified virions of adenovirus types 3, 4, 5, 7, 11, 14, 16, 21, 31, 34, 35, 37, and 41 were prepared as described elsewhere (42).

Fluorescent focus assay.

This experiment was performed essentially as described previously (29a). Briefly, in order to obtain synchronized infections of CHO cells, 1.2 × 105 to 1.5 × 105 adherent cells per well in 24-well plates were incubated for 1 h on ice with 1 ml of medium containing virions corresponding to 5 × 105 physical particles/cell. The corresponding amount of virions added to A549 cells was optimized to infect approximately 5% of the cells in each well. Unbound virions were removed by washing. Where indicated, for preincubations prior to infection, rabbit anti-CD46 serum (5 μl/well) was diluted in 300 μl Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 1% FCS, HEPES, and penicillin-streptomycin and incubated with the cells for 1 h on ice. After addition of virions, the cells were incubated for 44 h at 37°C, fixed in 99% methanol, and stained as described previously (6). Infected cells were examined (counted) in a fluorescence microscope. Homotypic polyclonal antisera were used, with one exception: for detection of Ad50 antigens, we used Ad3 serum.

DNA sequencing.

Genomic Ad50 DNA, from prototype strain Wan, was extracted from CsCl-purified virions by using the QIAamp DNA blood minikit blood and body fluid spin protocol (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The sequence reaction was then carried out using a BigDye Terminator v1.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), with the following primers (all from DNA Technology A/S, Aarhus, Denmark): 5′-GTT GCA TAT GAC CAA GAG AGT CCG G-3′, 5′-AAC GGA GGA CTT GTT AAT GGC-3′, 5′-GAA ATC GTA CGG CTG TTT AGC-3′, 5′-TTC AGC GGC ATA CTT TCT CC-3′, 5′-TCC CTC TTC CCA ACT CTG G-3′, 5′ GGT TGC CAT CGT TTG TAT CAG TG-3′, 5′-GAA GGG GGA GGC AAA ATA AC-3′, and 5′-AGG TCC CAT CAG TGT CAT CC-3′. DNA sequencing was performed on an ABI PRISM 377 DNA sequencer. Assembly and analysis of the Ad50 sequences were done using SeqMan software from the Lasergene package (DNAStar, Inc., Madison, WI). Amino acid homologies were calculated, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed (Clustal method, PAM250 matrix) using MegAlign software from the Lasergene package. Alignment of the amino acid sequences of the knob domains from multiple adenoviruses was done using the PAM250 matrix in ESPript 2.2 (22) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Alignment of the species B fiber knob amino acid sequencesa

| Serotype | % Identity with:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ad3 | Ad7 | Ad16 | Ad21 | Ad50 | Ad11 | Ad14 | Ad34 | Ad35 | |

| Ad3 | 100.0 | 45.7 | 61.7 | 47.9 | 48.4 | 45.2 | 43.6 | 46.8 | 46.8 |

| Ad7 | 100.0 | 46.4 | 43.5 | 44.0 | 92.7 | 90.2 | 43.5 | 44.0 | |

| Ad16 | 100.0 | 47.1 | 48.2 | 46.4 | 43.8 | 46.6 | 47.1 | ||

| Ad21 | 100.0 | 96.9 | 42.9 | 41.4 | 91.6 | 91.6 | |||

| Ad50 | 100.0 | 44.0 | 42.4 | 93.2 | 93.2 | ||||

| Ad11 | 100.0 | 92.7 | 44.0 | 44.0 | |||||

| Ad14 | 100.0 | 42.4 | 42.4 | ||||||

| Ad34 | 100.0 | 99.0 | |||||||

| Ad35 | 100.0 | ||||||||

Similarity table (% identity) of all species B adenoviruses. The sequences were aligned from the TLWT hinge to the translational stop codon as described in Materials and Methods.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The complete fiber gene of Ad50p has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AY887108. The accession numbers (NCBI/Entrez protein database) for fiber knobs of other adenoviruses are CAA51900 (Ad12, species A); CAA54050 (Ad31, A); CAA26029 (Ad3, B1); ERADF7 (Ad7, B1); AAA67203 (Ad16, B1;, AAA16493 (Ad21, B1); NP_852715 (Ad11, B2); BAB83691 (Ad14, B2); BAB70474 (Ad34, B2); AAN17490 (Ad35, B2); AP_000226 (Ad5, C); AAB71734 (Ad37, D); AAA42507 (Ad4, E); and ERADN2 (Ad41 long fiber; F).

RESULTS

Expression of human CD46 on CHO cells promoted infection of all species B adenoviruses except Ad3 and Ad7.

Based on multiple in vitro experiments, Roelvink et al. concluded that adenovirus serotypes from species A, C, D, E, and F (but not B) all use CAR as a cellular fiber receptor (30). From this study, it was stated that both Ad9 and Ad19 interact with CAR and further suggested that these viruses can use CAR as a cellular receptor. However, no studies were undertaken to show that CAR promoted entry and productive infection in target cells (i.e., served as a functional receptor). Based on the high amino acid homologies in the fiber knob domains of Ad9 and Ad8 (95%), it was suggested that Ad8 would also bind CAR.

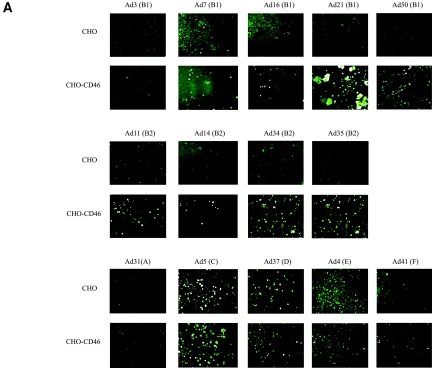

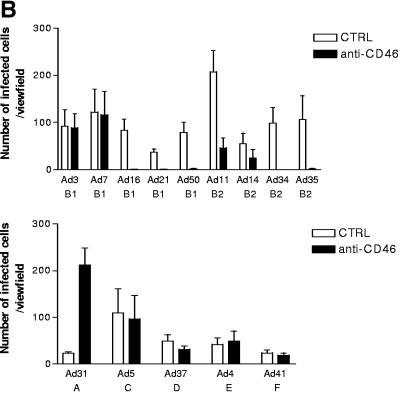

Currently it is known that Ad8, Ad19, and Ad37, which are the main causative agents of epidemic keratoconjunctivitis, all use sialic acid as a functional, cellular receptor instead of CAR (2-6, 11, 12). Moreover, the importance of complementing attachment studies with entry or replication studies is further emphasized by our previous finding that Ad7 binds more efficiently to CHO-CD46 cells than to CHO cells but does not infect CHO-CD46 cells more efficiently than CHO cells (35). Thus, Gaggar and coworkers showed that six species B adenoviruses attached more efficiently to CD46-expressing CHO cells than to CD46-negative CHO cells but did not show that the majority of these viruses infected CHO-CD46 cells more efficiently than CHO cells (21). One serotype (Ad35) was shown to infect target cells by means of CD46 as a functional cellular receptor. Thus, since attachment studies alone are insufficient to demonstrate functionality of a certain receptor (i.e., a receptor that promotes not only attachment but also subsequent entry and productive replication), we set out to identify which species B serotypes used CD46 as a functional cellular receptor. We found that all species B adenoviruses except Ad3 and Ad7 infected CD46-expressing CHO cells more efficiently than their CD46-negative counterparts, indicating that CD46 serves as a functional cellular receptor for all species B adenoviruses except Ad3 and Ad7 (Fig. 1). According to Gaggar et al., Ad50 interacted most efficiently with CHO-CD46 cells (compared to CHO cells), followed by Ad21, Ad16, and Ad11 (21). In our assay, Ad50 and Ad11 infected CHO-CD46 cells most efficiently, followed by the group of Ad16, Ad21, Ad34, and Ad35. Under the conditions used, CD46 did not render CHO cells more permissive for infection by any of the serotypes selected from other species. Ad31 (species A), Ad4 (species E), and Ad41 (species F) were almost completely unable to infect CHO cells, regardless of CD46 expression, whereas Ad5 and Ad37 both infected the two cell lines with similar efficiencies.

FIG. 1.

All species B adenoviruses except Ad3 and Ad7 infect CHO-CD46 cells more efficiently than CHO cells. (A) CHO or CHO-CD46 cells were infected with purified virions, stained with homotypic rabbit anti-CD46 polyclonal sera and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-immunoglobulin G antibodies, and analyzed for infected cells as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Quantification of infected cells.

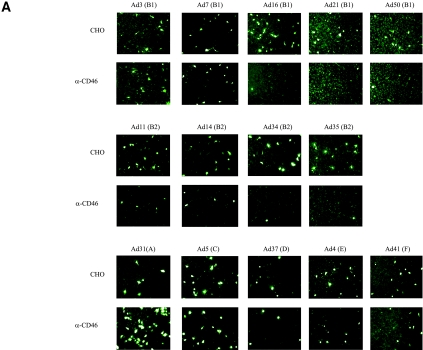

CD46 antiserum efficiently inhibited the infectivities of all species B adenoviruses in A549 cells, except Ad3 and Ad7.

When expressed in trans, human CD46 did indeed enable attachment of several species B adenoviruses to CHO cells, as well as subsequent entry and replication of a chimeric Ad5 adenovirus consisting of the Ad5 capsid and the Ad35 fiber knob domain (21); such experiments alone, or together, are not sufficient to prove that CD46 is a major functional cellular receptor for most (if not all) species B adenoviruses. To ascertain whether CD46 might play this role, we infected the human respiratory epithelial cell line A549, a cell line that represents the (respiratory) tropism of all species B adenoviruses, with purified species B virions in the presence of rabbit antiserum against human CD46. This serum completely blocked the infectivities of Ad16, Ad21, and Ad50 (all of subspecies B1) and of Ad34 and Ad35 (subspecies B2) (Fig. 2). The infectivities of both Ad11 and Ad14 (B2) were efficiently inhibited but not completely blocked, whereas the infectivities of Ad3 and Ad7 (B1) were unaffected. None of the serotypes belonging to species C (Ad5), D (Ad37), E (Ad4), or F (Ad41) exhibited a significant change in infectivity toward A549 cells in the presence of antiserum against CD46. However, to our surprise, Ad31 (of species A) infected A549 cells more efficiently in the presence of CD46 antiserum.

FIG. 2.

Rabbit anti-CD46 serum inhibits the infectivities of all species B adenoviruses in A549 cells, except Ad3 and Ad7. (A) A549 cells were preincubated with rabbit anti-CD46 (α-CD46) serum, infected with purified virions, stained with homotypic rabbit anti-CD46 polyclonal sera and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-immunoglobulin G antibodies, and analyzed for infected cells as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Quantification of infected cells. CTRL, control.

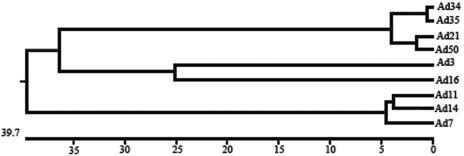

The fiber knob domains of all species B adenoviruses except Ad3 and Ad7 contain exposed acidic amino acids at position 296.

With few exceptions, the mechanism by which adenoviruses interact with their cellular receptors, including CD46, has been shown to involve the knob domain of the viral fiber protein. Until this study, all fiber genes of species B adenoviruses had been sequenced except for that of Ad50. Thus, in order to obtain a complete picture of the fiber sequences of species B adenoviruses, we sequenced the fiber gene of Ad50. The deduced amino acid sequence was organized as for those of most species B adenovirus fibers, in that there was an N-terminal tail, a shaft consisting of six repetitive motifs, and a C-terminal knob domain. At the amino acid level, the knob of Ad50 was most homologous to those of Ad21 (97%), Ad34 (93%), and Ad35 (93%), followed by those of Ad3 (48%), Ad16 (48%), Ad7 (44%), Ad11 (44%), and Ad14 (42%) (Fig. 3). By aligning the amino acid sequences of the knob domains of the fibers of all species B adenoviruses and comparing these sequences with the corresponding sequences of adenoviruses from other species, we found that all species B adenoviruses (but not adenoviruses from other serotypes) contain a three-amino-acid insert in the otherwise-conserved AB loop (Fig. 4), which has previously been suggested to contain a CAR-interacting motif in the knobs of serotypes other than B (10, 31). We also identified two residues that discriminate the knobs of Ad3 and Ad7 from the knobs of the other species B adenoviruses. These two viruses contain the hydrophobic amino acid leucine or valine at positions 240 and 296, whereas the other species B adenoviruses contain charged or hydrophilic amino acids at position 240 and negatively charged amino acids only at position 296. These two residues are positioned close to previously known receptor-interacting regions in other adenoviruses, corresponding to the CAR-binding site of Ad12 (residue 240 [10]) and the sialic acid-binding site of Ad37 (residue 296 [11]). Since the overall structure of the knobs is well conserved between species, this suggests that these residues are exposed and possibly able to interact with cell surface receptors.

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of the knob domains of species B adenovirus fibers. The length of each pair of branches represents the distance between sequence pairs, while the units at the bottom of the tree indicate the number of substitution events. The sequences were aligned from the TLWT hinge to the translational stop codon, as described in Materials and Methods.

FIG. 4.

Alignment of the knob domains of selected adenovirus serotypes. The amino acid sequences of the knob domains of multiple adenovirus serotypes were aligned using ESPript 2.2 software, as described in Materials and Methods. Secondary structure elements and numbering, according to the Ad3 fiber amino acid sequence and three-dimensional structure (20), are shown above the alignment (arrows represent beta-strands). Completely conserved residues are marked with a red background, and highly conserved residues are red letters surrounded by blue boxes. The three-amino-acid inserts in the AB loop of the knobs of species B adenoviruses are boxed in green. The two hydrophobic residues (240 and 296) that are unique for the knobs of Ad3 and Ad7 are marked with a green background. Residues in the knob of Ad12 that are of importance for the interaction with CAR (10) are marked with a yellow background. Residues in the knob of Ad5 that are of importance for the interaction with CAR according to Roelvink et al. (31) are marked with an orange background. Residues in the knob of Ad5 that are of importance for the interaction with CAR according to Kirby et al. (25) are boxed in black. The two key residues (Y256 and K295) that form the sialic acid-binding site in the knob of Ad37 (11) are marked with a blue background, whereas the two other sialic acid-interacting residues (forming weaker hydrogen bonds) are boxed in cyan. The two residues that differ between Ad37 and Ad19p (a serotype that does not use sialic acid as a cellular receptor [3, 4]) are marked with a cyan background.

DISCUSSION

None of the serotypes belonging to species C (Ad5), D (Ad37), E (Ad4), or F (Ad41) infected target cells by means of CD46 in this study, indicating that Ad5, Ad37, Ad4, Ad41, and Ad31 do not use CD46 as a functional cellular receptor. Two other interesting observations were that Ad37, which has been suggested to use CD46 as a cellular receptor (46), did not infect CHO-CD46 cells more efficiently than CHO cells and that its infectivity toward A549 cells was not affected much when these cells were preincubated with CD46 antiserum. The other interesting observation was that Ad31 infected A549 cells more efficiently in the presence of CD46 antiserum. The reason for this is unclear at present.

Although several reports have characterized the receptors used by one or more species B adenovirus serotypes, it has been unclear which serotypes use CD46 as a functional cellular receptor, i.e., a cellular receptor that mediates not only attachment to host cells but also subsequent entry and productive infection. Gaggar and coworkers recently stated that CD46 is a cellular receptor for species B serotypes (21). This was based on experiments mainly using Ad35 and a chimeric, green fluorescent protein-expressing adenovirus consisting of the Ad5 virion pseudotargeted with the Ad35 fiber knob. However, in order to state that CD46 serves as a cellular receptor for (most/all) species B viruses, attachment studies alone are not sufficient. Moreover, out of the nine species B serotypes, only seven were included in the work of Gaggar et al. Of these seven, six serotypes attached to CHO-CD46 cells more efficiently than to CD46 negative CHO-cells. Thus, until now, two serotypes (Ad7 and Ad34) had never before been investigated for usage of CD46 as a cellular receptor, and in the case of Ad3, this virus did not attach to CHO-CD46 cells more efficiently than to ordinary CHO cells in the cited study.

In this work, we included all nine species B adenoviruses and determined receptor specificity as a function of productive replication in target cells. We found that seven out of nine species B serotypes (Ad16, Ad21, and Ad50 of subspecies B1 and Ad11, Ad14, Ad34, and Ad35 of subspecies B2) infected target cells by means of CD46. In the study of Gaggar et al. (21), Ad50 appeared to be superior to the other viruses in binding to CHO-CD46 cells, but in our hands, this result was not seen with the infectivity assay using similar cells (Fig. 1). However, one possible explanation could be the usage of different isoforms. Whereas we used CHO cells transfected with cDNA encoding the BC1 isoform of CD46, Gaggar et al. used CHO cells transfected with cDNA encoding the C2 isoform. Thus, there are differences in both the extra- and the intracellular domains of CD46. Taken together, our results demonstrate that CD46 is not a cellular receptor for species B2 viruses only, as suggested previously (34), but is the major functional cellular receptor in A549 cells for all species B adenoviruses except Ad3 and Ad7 (Fig. 2).

The two most common species B serotypes in the human population, Ad3 and Ad7 (40), did not use CD46 as a functional cellular receptor in our study. This is partially supported by the binding experiments performed by Gaggar et al. (21) but contradicts the data presented by Sirena et al. (38). However, the data provided by Sirena and coworkers indicated that there was an interaction between the Ad3 knob and CD46 on erythroleukemia K562 cells and epithelial (genital) HeLa cells, which, as far as we know, do not represent the tropism of Ad3. Also, a mixture of seven antibodies against CD46 inhibited Ad3 binding to target cells by only 50%. Similarly, Ad7 has been shown to bind more efficiently to CHO-CD46 cells than to CD46-negative CHO cells but does not infect CHO-CD46 cells more efficiently than CD46-negative CHO cells (reference 35 and this publication). Since interactions with the BC1 isoform were investigated both by Sirena et al. (BHK-CD46-cl54) and by us (CHO-CD46), different isoforms should not account for the different results obtained. Taken together, these data suggest that even if Ad3 and Ad7 may interact with CD46, and perhaps use CD46 as a coreceptor, Ad3 and probably also Ad7 are likely to use cell surface components other than CD46 as major functional cellular receptors. In agreement with this, it was recently demonstrated that Ad3 uses CD80 and CD86, which are costimulatory molecules present on mature dendritic cells and B lymphocytes, as cellular attachment receptors (37). Even though these cells, to the best of our knowledge, do not represent the major target cells for Ad3, as suggested by Short et al. (37), Ad3 may have evolved towards utilization of CD80/CD86 as cellular receptors when infecting antigen-presenting (dendritic) cells as a means of modulating an immune response to the viral infection. It may also be that the expression levels of CD80 and CD86 are broader than previously thought, and they may be expressed on epithelial cells as well. This suggestion is supported by findings showing that CD80 and CD86 are indeed also expressed on human primary respiratory epithelial cells (32). If so, it may even be that CD80 and CD86 act as the major cellular receptors for Ad3.

Another possibility, although less likely, is that CD46, when expressed in trans as in CHO-CD46 cells, also mediates increased binding of certain serotypes indirectly by transporting other potential receptors to the surface of the target cells. For example, CD46 has previously been shown to interact directly or indirectly with multiple β1-integrin heterodimers (29). The β1-integrin has a molecular mass (130 kDa) identical to that of an Ad3-interacting membrane protein previously isolated from HeLa cells (19). Since various β1-integrins have been demonstrated to serve both as secondary receptors for Ad5 (14, 33) and as primary receptors for other viruses (9, 44), upregulated expression of CD46 may facilitate usage of other potential adenovirus receptors such as β1-integrins. This could possibly explain the inconsistent results obtained regarding the receptors used by Ad3.

Early on, we suggested the presence of two different cellular receptors for species B adenoviruses (34, 35). It is now apparent that one of these receptors is CD46 and that CD80 and CD86 are additional candidate cellular receptors for species B adenoviruses. The major functional cellular receptor for Ad3 and Ad7 most probably remains to be identified, although it is too early to exclude both CD46 and CD80/CD86 from playing this role. Based on the suggestion that CD80 and CD86 are used by Ad3 as cellular attachment receptors on dendritic cells and lymphocytes (37), it would be very interesting to investigate whether Ad3 and Ad7, which in our hands are independent of CD46, use CD80 and CD86 as cellular receptors in human respiratory epithelial cells.

A striking difference between species B adenoviruses and the other adenoviruses investigated here is that all species B adenoviruses carry a three-amino-acid insert in the AB loop of the knob domain (Fig. 4), which is critical for CAR-interacting adenoviruses (10, 31). Together with the substitutions of CAR-interacting residues at positions 138, 140, and 141, this insert may contribute to the inability of species B adenoviruses to interact with CAR. It is, however, not yet known whether this insert promotes interactions with CD46 or CD80/CD86 or with other as-yet-uncharacterized receptors.

We have shown previously that the knobs of species D adenoviruses with strict ocular tropism (Ad8, Ad19a, and Ad37) exhibit a highly positively charged surface and that their interactions with negatively charged sialic acid receptors involve an electrostatic event (3, 5, 11). However, the theoretically calculated isoelectric points in the knobs of Ad3 and Ad7 do not differ noticeably from those of other species B adenoviruses (data not shown). Therefore, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the receptor specificity for Ad3 and Ad7 along the lines used to identify sialic acid as a receptor for Ad8, Ad19, and Ad37.

It has been suggested by others that it is highly likely that the receptor is the same for Ad3 and Ad7 and that exposed hydrophobic residues of Ad3 (and Ad7) could play a role in receptor binding (20). The knobs of Ad3 and Ad7 contain two hydrophobic amino acids that are unique within species B (residues 240 and 296). Whereas residue 296 is hydrophobic in Ad3 (leucine) and Ad7 (valine), all other species B adenoviruses contain an acidic amino acid in this residue (Fig. 4). This residue is exposed, according to the X-ray data of the Ad3 knob as presented in reference 20, supporting the suggestion that it may also be involved in receptor interactions. Our recent finding that a neighboring residue in the Ad37 knob (295Lys) interacts with sialic acid, the cellular receptor for Ad37 (11), further supports this suggestion. The other residue (residue 240) is also exposed, according to the X-ray data of the Ad3 knob (20). In Ad12, the corresponding region contains a second CAR-interacting site (10), supporting the hypothesis that this residue is exposed and may also contribute to receptor interactions. Thus, residues 240 and 296 of Ad3 and Ad7 are both likely to contribute to receptor interactions. However, additional domains of species B fiber knobs may be involved in receptor interactions, as has been shown for Ad2 and Ad12 regarding interactions with CAR (24), and mutation analysis of the knobs of species B adenoviruses is required to confirm the roles of residues 240 and 296. In summary, the data presented here will add to our knowledge of the cellular receptors used by human adenoviruses and may contribute to the development of adenovirus vectors for human gene therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Medical Faculty, Umeå University (Dnr 223-1087-03, 223-1141-04, and 223-2542-03), the Swedish Research Council (529-2003-6008, 521-2002-5981, and 521-2004-6174), the Swedish Society for Medical Research, and the Swedish Society for Medicine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adrian, T., G. Wadell, J. C. Hierholzer, and R. Wigand. 1986. DNA restriction analysis of adenovirus prototypes 1 to 41. Arch. Virol. 91:277-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnberg, N., K. Edlund, A. H. Kidd, and G. Wadell. 2000. Adenovirus type 37 uses sialic acid as a cellular receptor. J. Virol. 74:42-48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnberg, N., A. H. Kidd, K. Edlund, J. Nilsson, P. Pring-Åkerblom, and G. Wadell. 2002. Adenovirus type 37 binds to cell surface sialic acid through a charge-dependent interaction. Virology 302:33-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnberg, N., A. H. Kidd, K. Edlund, F. Olfat, and G. Wadell. 2000. Initial interactions of subgenus D adenoviruses with A549 cellular receptors: sialic acid versus αv integrins. J. Virol. 74:7691-7693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnberg, N., Y. Mei, and G. Wadell. 1997. Fiber genes of adenoviruses with tropism for the eye and the genital tract. Virology 227:239-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnberg, N., P. Pring-Åkerblom, and G. Wadell. 2002. Adenovirus type 37 uses sialic acid as a cellular receptor on Chang C cells. J. Virol. 76:8834-8841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benkö, M., B. Harrach, and W. C. Russell. 2000. Family adenoviridae, p. 227-238. In M. V. H. van Regenmortel, C. M. Fauquet, and D. H. L. Bishop (ed.), Virus taxonomy. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 8.Bergelson, J. M., J. A. Cunningham, G. Droguett, E. A. Kurt-Jones, A. Krithivas, J. S. Hong, M. S. Horwitz, R. L. Crowell, and R. W. Finberg. 1997. Isolation of a common receptor for coxsackie B viruses and adenoviruses 2 and 5. Science 275:1320-1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergelson, J. M., M. P. Shepley, B. M. Chan, M. E. Hemler, and R. W. Finberg. 1992. Identification of the integrin VLA-2 as a receptor for echovirus 1. Science 255:1718-1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bewley, M. C., K. Springer, Y. B. Zhang, P. Freimuth, and J. M. Flanagan. 1999. Structural analysis of the mechanism of adenovirus binding to its human cellular receptor, CAR. Science 286:1579-1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burmeister, W. P., D. Guilligay, S. Cusack, G. Wadell, and N. Arnberg. 2004. Crystal structure of species D adenovirus fiber knobs and their sialic acid binding sites. J. Virol. 78:7727-7736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cashman, S. M., D. J. Morris, and R. Kumar-Singh. 2004. Adenovirus type 5 pseudotyped with adenovirus type 37 fiber uses sialic acid as a cellular receptor. Virology 324:129-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu, Y., D. Heistad, M. I. Cybulsky, and B. L. Davidson. 2001. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 augments adenovirus-mediated gene transfer. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 21:238-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davison, E., I. Kirby, J. Whitehouse, I. Hart, J. F. Marshall, and G. Santis. 2001. Adenovirus type 5 uptake by lung adenocarcinoma cells in culture correlates with Ad5 fibre binding is mediated by alpha(v)beta1 integrin and can be modulated by changes in beta1 integrin function. J. Gene Med. 3:550-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dechecchi, M. C., P. Melotti, A. Bonizzato, M. Santacatterina, M. Chilosi, and G. Cabrini. 2001. Heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans are receptors sufficient to mediate initial binding of adenovirus types 2 and 5. J. Virol. 75:8772-8780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dechecchi, M. C., A. Tamanini, A. Bonizzato, and G. Cabrini. 2000. Heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans are involved in adenovirus type 5 and 2-host cell interactions. Virology 268:382-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Defer, C., M. T. Belin, M. L. Caillet-Boudin, and P. Boulanger. 1990. Human adenovirus-host cell interactions: comparative study with members of subgroups B and C. J. Virol. 64:3661-3673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Jong, J. C., A. G. Wermenbol, M. W. Verweij-Uijterwaal, K. W. Slaterus, P. Wertheim-Van Dillen, G. J. J. Van Doornum, S. H. Khoo, and J. C. Hierholzer. 1999. Adenoviruses from human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals, including two strains that represent new candidate serotypes Ad50 and Ad51 of species B1 and D, respectively. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3940-3945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Guilmi, A. M., A. Barge, P. Kitts, E. Gout, and J. Chroboczek. 1995. Human adenovirus serotype 3 (Ad3) and the Ad3 fiber protein bind to a 130-kDa membrane protein on HeLa cells. Virus Res. 38:71-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durmort, C., C. Stehlin, G. Schoehn, A. Mitraki, E. Drouet, S. Cusack, and W. P. Burmeister. 2001. Structure of the fiber head of Ad3, a non-CAR-binding serotype of adenovirus. Virology 285:302-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaggar, A., D. M. Shayakhmetov, and A. Lieber. 2003. CD46 is a cellular receptor for group B adenoviruses. Nat. Med. 9:1408-1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gouet, P., E. Courcelle, D. I. Stuart, and F. Metoz. 1999. ESPript: analysis of multiple sequence alignments in PostScript. Bioinformatics 15:305-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong, S. S., L. Karayan, J. Tournier, D. T. Curiel, and P. A. Boulanger. 1997. Adenovirus type 5 fiber knob binds to MHC class I alpha2 domain at the surface of human epithelial and B lymphoblastoid cells. EMBO J. 16:2294-2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howitt, J., M. C. Bewley, V. Graziano, J. M. Flanagan, and P. Freimuth. 2003. Structural basis for variation in adenovirus affinity for the cellular coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 278:26208-26215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirby, I., E. Davison, A. J. Beavil, C. P. Soh, T. J. Wickham, P. W. Roelvink, I. Kovesdi, B. J. Sutton, and G. Santis. 2000. Identification of contact residues and definition of the CAR-binding site of adenovirus type 5 fiber protein. J. Virol. 74:2804-2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kojaoghlanian, T., P. Flomenberg, and M. S. Horwitz. 2003. The impact of adenovirus infection on the immunocompromised host. Rev. Med. Virol. 13:155-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leen, A. M., and C. M. Rooney. 2005. Adenovirus as an emerging pathogen in immunocompromised patients. Br. J. Haematol. 128:135-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liszewski, M. K., and J. P. Atkinson. 1996. Membrane cofactor protein (MCP; CD46). Isoforms differ in protection against the classical pathway of complement. J. Immunol. 156:4415-4421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lozahic, S., D. Christiansen, S. Manie, D. Gerlier, M. Billard, C. Boucheix, and E. Rubinstein. 2000. CD46 (membrane cofactor protein) associates with multiple beta1 integrins and tetraspans. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:900-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29a.Philipson, L. 1961. Adenovirus assay by the fluorescent cell-counting procedure. Virology 15:263-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roelvink, P. W., A. Lizonova, J. G. M. Lee, Y. Li, J. M. Bergelson, R. W. Finberg, D. E. Brough, I. Kovesdi, and T. J. Wickham. 1998. The coxsackievirus-adenovirus receptor protein can function as a cellular attachment protein for adenovirus serotypes from subgroups A, C, D, E, and F. J. Virol. 72:7909-7915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roelvink, P. W., G. Mi Lee, D. A. Einfeld, I. Kovesdi, and T. J. Wickham. 1999. Identification of a conserved receptor-binding site on the fiber proteins of CAR-recognizing adenoviridae. Science 286:1568-1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salik, E., M. Tyorkin, S. Mohan, I. George, K. Becker, E. Oei, T. Kalb, and K. Sperber. 1999. Antigen trafficking and accessory cell function in respiratory epithelial cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 21:365-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salone, B., Y. Martina, S. Piersanti, E. Cundari, G. Cherubini, L. Franqueville, C. M. Failla, P. Boulanger, and I. Saggio. 2003. Integrin α3β1 is an alternative cellular receptor for adenovirus serotype 5. J. Virol. 77:13448-13454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Segerman, A., N. Arnberg, A. Erikson, K. Lindman, and G. Wadell. 2003. There are two different species B adenovirus receptors: sBAR, common to species B1 and B2 adenoviruses, and sB2AR, exclusively used by species B2 adenoviruses. J. Virol. 77:1157-1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Segerman, A., J. P. Atkinson, M. Marttila, V. Dennerquist, G. Wadell, and N. Arnberg. 2003. Adenovirus type 11 uses CD46 as a cellular receptor. J. Virol. 77:9183-9191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shenk, T. 2001. Adenoviridae: the viruses and their replication., p. 2265-2300. In D. M. Knipe, P. M. Howley, D. E. Griffin, R. A. Lamb, M. A. Martin, B. Roizman, and S. E. Straus (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed., vol. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Short, J. J., A. V. Pereboev, Y. Kawakami, C. Vasu, M. J. Holterman, and D. T. Curiel. 2004. Adenovirus serotype 3 utilizes CD80 (B7.1) and CD86 (B7.2) as cellular attachment receptors. Virology 322:349-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sirena, D., B. Lilienfeld, M. Eisenhut, S. Kalin, K. Boucke, R. R. Beerli, L. Vogt, C. Ruedl, M. F. Bachmann, U. F. Greber, and S. Hemmi. 2004. The human membrane cofactor CD46 is a receptor for species B adenovirus serotype 3. J. Virol. 78:4454-4462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tomko, R. P., R. Xu, and L. Philipson. 1997. HCAR and MCAR: the human and mouse cellular receptors for subgroup C adenoviruses and group B coxsackieviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:3352-3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vogels, R., D. Zuijdgeest, R. van Rijnsoever, E. Hartkoorn, I. Damen, M.-P. de Béthune, S. Kostense, G. Penders, N. Helmus, W. Koudstaal, M. Cecchini, A. Wetterwald, M. Sprangers, A. Lemckert, O. Ophorst, B. Koel, M. van Meerendonk, P. Quax, L. Panitti, J. Grimbergen, A. Bout, J. Goudsmit, and M. Havenga. 2003. Replication-deficient human adenovirus type 35 vectors for gene transfer and vaccination: efficient human cell infection and bypass of preexisting adenovirus immunity. J. Virol. 77:8263-8271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wadell, G. 2000. Adenoviruses, p. 308-327. In A. J. Zuckerman, J. E. Banatvala, and J. R. Pattison (ed.), Principles and practice of clinical virology, 4th ed. John Wiley & Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 42.Wadell, G., A. Allard, and J. C. Hierholzer. 1999. Adenoviruses, p. 970-982. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, M. A. Pfaller, F. C. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 7th ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 43.Wadell, G., M.-L. Hammarskjöld, G. Winberg, M. Varsanyi, and G. Sundell. 1980. Genetic variability of adenoviruses. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 354:16-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weigel-Kelley, K. A., M. C. Yoder, and A. Srivastava. 2003. Alpha5beta1 integrin as a cellular coreceptor for human parvovirus B19: requirement of functional activation of beta1 integrin for viral entry. Blood 102:3927-3933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wickham, T. J., P. Mathias, D. A. Cheresh, and G. R. Nemerow. 1993. Integrins alpha v beta 3 and alpha v beta 5 promote adenovirus internalization but not virus attachment. Cell 73:309-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu, E., S. A. Trauger, L. Pache, T. M. Mullen, D. J. von Seggern, G. Siuzdak, and G. R. Nemerow. 2004. Membrane cofactor protein is a receptor for adenoviruses associated with epidemic keratoconjunctivitis. J. Virol. 78:3897-3905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]