Abstract

The ability to change between yeast and hyphal cells (dimorphism) is known to be a virulence property of the human pathogen Candida albicans. The pathogenesis of disseminated candidosis involves adhesion and penetration of hyphal cells from a colonized mucosal site to internal organs. Parenchymal organs, such as the liver and pancreas, are invaded by C. albicans wild-type hyphal cells between 4 and 24 h after intraperitoneal (i.p.) infection of mice. In contrast, a hypha-deficient mutant lacking the transcription factor Efg1 was not able to invade or damage these organs. To investigate whether this was due to the inability to undergo the dimorphic transition or due to the lack of hypha-associated factors, we investigated the role of secreted aspartic proteinases during tissue invasion and their association with the different morphologies of C. albicans. Wild-type cells expressed a distinct pattern of SAP genes during i.p. infections. Within the first 72 h after infection, SAP1, SAP2, SAP4, SAP5, SAP6, and SAP9 were the most commonly expressed proteinase genes. Sap1 to Sap3 antigens were found on yeast and hyphal cells, while Sap4 to Sap6 antigens were predominantly found on hyphal cells in close contact with host cells, in particular, eosinophilic leukocytes. Mutants lacking EFG1 had either noticeably reduced or higher expressed levels of SAP4 to SAP6 transcripts in vitro depending on the culture conditions. During infection, efg1 mutants had a strongly reduced ability to produce hyphae, which was associated with reduced levels of SAP4 to SAP6 transcripts. Mutants lacking SAP1 to SAP3 had invasive properties indistinguishable from those of wild-type cells. In contrast, a triple mutant lacking SAP4 to SAP6 showed strongly reduced invasiveness but still produced hyphal cells. When the tissue damage of liver and pancreas caused by single sap4, sap5, and sap6 and double sap4 and -6, sap5 and -6, and sap4 and -5 double mutants was compared to the damage caused by wild-type cells, all mutants which lacked functional SAP6 showed significantly reduced tissue damage. These data demonstrate that strains which produce hyphal cells but lack hypha-associated proteinases, particularly that encoded by SAP6, are less invasive. In addition, it can be concluded that the reduced virulence of hypha-deficient mutants is not only due to the inability to form hyphae but also due to modified expression of the SAP genes normally associated with the hyphal morphology.

Among human pathogenic fungi, Candida albicans, a polymorphic yeast, has a dominant role of increasing medical importance. Although considered a harmless commensal in healthy individuals, this fungus frequently causes superficial infections of mucosa and skin under certain conditions, for example, when the normal microbial flora is unbalanced due to extensive antibacterial treatment. In immunocompromised patients, however, C. albicans may invade deeper tissues, penetrate the blood vessel system, and cause life-threatening systemic infections (30). Therefore, this fungus has adapted not only to epithelial cells but also to a number of different tissues at various stages of an infection. While physical barriers and the immune system of the host are the crucial factors which control the commensal stage, a number of fungal virulence attributes must stand by to be expressed and required depending on the site and stage of invasion and the nature of the host response (31). Furthermore, the virulence properties must be highly adapted to the different environments, for example, oral mucosa, blood, or parenchymal organs. One of these factors is the ability of C. albicans to grow as spherical yeast cells or in long filamentous hyphal cells (dimorphism) (2, 6). Hyphae are commonly thought of as the more invasive form and are frequently identified in infected tissue. Hypha-deficient mutants are also known to be avirulent in systemic infections (22, 41). The fact that the dimorphic transition is regulated by a number of possible cross-talking signal transduction pathways (2, 6) underlines the importance of this morphological flexibility. However, the defined function of hyphal formation and the reason why hypha-deficient mutants are avirulent are still unknown.

Another important virulence attribute of C. albicans is extracellular proteolytic activity due to secreted aspartic proteinases encoded by a gene family of at least 10 genes (SAP genes; accession no. for SAP10, AF146440) (26, 27). One possible explanation for the existence of such a large number of different SAP genes may be the necessity for specific and optimized proteinases during the different stages of an infection (15). In fact, SAP genes were shown to be expressed differentially according to the morphological form of the fungus and the surrounding environment supporting such a transition (12, 29, 35). Furthermore, purified Sap enzymes were shown to have different pH optima (1) and different substrate specificities (18). In addition, the disruption of certain SAP genes (SAP1 to SAP3) had a strong influence on the course of superficial infections, while the disruption of other SAP genes (SAP4 to SAP6) did not (5, 36).

Additional virulence attributes, such as adhesion factors (11, 42), thigmotropism (38), phenotypic switching (39), and other hydrolytic enzymes (14, 16) have been identified in C. albicans. All of these factors may be adapted to distinct stages or types of infection and are postulated to act in concert to facilitate fungal survival during the course of infections (4, 31). We show here that the ability to switch between a yeast and hyphal form itself does not fulfill the requirement of invasion properties when hypha-associated factors, such as Sap proteinases, are lacking. These proteinases are expressed at distinct stages of a systemic infection and are responsible for tissue damage of infected organs. Furthermore, our data suggest that the reduced virulence of hypha-deficient mutants may be at least in part due to the lack of expression of hypha-associated proteinases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

In this study, the clinical C. albicans wild-type strain SC5314 (9) and the following strains derived from it were used: the URA3/ura3 heterozygote CAF2-1 and ura3/ura3 homozygote CAI4 (7); strains with the sap single, double, and triple null mutations sap4, sap5, sap6, sap4 and -6, sap1 to sap3, and sap4 to sap6 (13, 20, 34); and the hypha-deficient efg1 (41), cph1, and efg1/cph1 (22) mutants. The sap4 and -5 and sap5 and -6 double mutants were produced in this study by using the disruption cassettes and procedure described previously (34). To restore SAP6 expression in the sap6 null mutant, a 3,213-bp PCR-amplified fragment of SAP6 containing 1,737-bp 5′ and 219-bp 3′ untranslated regions of the gene was cloned into TOPO-XL (Invitrogen), released with SacI and NotI, and cloned into the SacI and NotI sites of pCIp10 (28) to give pAF3. The plasmid containing SAP6 (pAF3) was transformed into the Ura− sap6 null (Δsap6::hisG/Δsap6::hisG) mutant (34). The Ura− wild type (CAI4) and the Ura− sap6 null (Δsap6::hisG/Δsap6::hisG) mutant were also transformed with pCIp10 alone and used as controls. Ura+ colonies transformed with pAF3 or pCIp10 were tested for growth in minimal medium, their integration at the RP10 locus by Southern analysis, and their ability to express SAP6 by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). Selected positive transformants were used for animal infections. Primers used to amplify SAP6 were 5′-AGGCCTTGACATAGTACGCCTCAAATGGAAG-3′ and 5′-AAGGCCTTTATCACTACATTAAAGTTCACTCAC-3′. All strains are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Parental strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| SC5314 | URA3/URA3 | 9 | |

| CAF2-1 | SC5314 | URA3/ura3 | 7 |

| CAI4 | SC5314 | ura3/ura3 | 7 |

| CAF4-2 | SC5314 | ura3/ura3 | 7 |

| M1060 | CAI4 | ura3/ura3 pCIp10 (URA3) | This study |

| DSY436 (sap4) | CAF4-2 | Δsap4::hisG/sap4::hisG-URA3-hisG | 34 |

| DSY438 | DSY436 | Δsap4::hisG/sap4::hisG | 34 |

| DSY452 (sap5) | CAF4-2 | Δsap5::hisG/Δsap5::hisG-URA3-hisG | 34 |

| DSY344 | CAF4-2 | Δsap6::hisG-URA3-hisG/SAP6 | 34 |

| DSY345 | CAF4-2 | Δsap6::hisG/SAP6 | 34 |

| DSY346 (sap6) | CAF4-2 | Δsap6::hisG/Δsap6::hisG-URA3-hisG | 34 |

| DSY349 | CAF4-2 | Δsap6::hisG/Δsap6::hisG | 34 |

| M1065 | DSY349 | Δsap6::hisG/Δsap6::hisG pCIp10 | This study |

| M1067 | DSY349 | Δsap6::hisG/Δsap6::hisG pCIp10-SAP6 (pAF3) | This study |

| M28 (sap4 and −5) | DSY438 | Δsap4::hisG/sap4::hisG Δsap5::hisG/Δsap5::hisG-URA3-hisG | This study |

| M30 (sap4 and −6) | DSY349 | Δsap6::hisG/Δsap6::hisG Δsap4::hisG/sap4::hisG-URA3-hisG | 34 |

| DSY439 | DSY437 | Δsap6::hisG/Δsap6::hisG Δsap4::hisG/sap4::hisG | 34 |

| DSY437 (sap5 and −6) | DSY435 | Δsap6::hisG/Δsap6::hisG Δsap5::hisG/Δsap5::hisG-URA3-hisG | This study |

| DSY459 (sap4 to −6) | DSY439 | Δsap6::hisG/Δsap6::hisG Δsap4::hisG/sap4::hisG Δsap5::hisG/Δsap5::hisG-URA3-hisG | 34 |

| M119 (sap1 to −3) | M118 | Δsap1::hisG/Δsap1::hisG Δsap2::hisG/Δsap2::hisG Δsap3::hisG/Δsap3::hisG::URA3::hisG | 20 |

| HLC52 (efg1) | CAI4 | Δefg1::hisG/Δefg1::hisG::URA3::hisG | 22 |

| JKC19 (cph1) | CAI4 | Δcph1::hisG/Δcph1::hisG::URA3::hisG | 22 |

| HLC54 (efg1/cph1) | CAI4 | Δcph1::hisG/Δcph1::hisG Δefg1::hisG/Δefg1::hisG::URA3::hisG | 22 |

Hyphal induction.

In order to investigate SAP gene expression in wild-type and mutant cells in vitro, we induced hyphal formation by the addition of calf serum (10) or a regimen of pH- and temperature-regulated transition (3). Precultures were incubated at 25°C for 12 to 24 h in Lee's medium, pH 4.5 (3), and used to inoculate (<2 × 106 cells/ml) prewarmed (37°C) induction media. Calf serum (5%) was used for serum induction. Total cell numbers and the percentage of hyphal cells were determined for the preculture and 30, 60, 120, and 180 min after induction. Cells were harvested at the same time points for RNA extraction.

Infection model and tissue processing.

To obtain infected organs, BALB/c mice were infected intraperitoneally with a sublethal dose of 108 Candida cells per mouse as described by Kretschmar et al. (19). With this inoculum size, wild-type C. albicans SC5314 cells were eliminated from the mice within 10 days postinfection (not shown). Prior to injection, cells were grown in Sabouraud broth medium and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline. Mice were killed by cervical dislocation 4, 8, 24, and 72 h after infection. Invasion zones of infected organs were removed aseptically, and each zone was divided into two parts; one was weighed and used for CFU determination, and the other was shock frozen and used to isolate total RNA or embedded in paraffin after fixation in phosphate-buffered formaldehyde and used to prepare histological sections. Tissue sections were paraffin embedded, cut, and stained as described by Kretschmar et al. (19). Selected tissue samples were also used for immunoelectron microscopy.

Immunoelectron microscopy.

Electron microscopy and postembedding immunogold labeling of sections of infected organs were performed as described by Schaller et al. (35, 36). Tissue sections were incubated with anti-Sap polyclonal rabbit antibodies, directed against Sap1 to Sap3 or against Sap4 to Sap6 (1).

RNA isolation and RT-PCR.

Total RNA from shock-frozen culture pellets and infected organs was isolated with RNAPure (Peqlab Biotechnologie, Erlangen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNAPure is based on phenol and guanidinium isothiocyanate and was used to isolate RNA from lysed cells. To lyse the cells and tissue in the infected organs, organs were homogenized with an Ultra-Turrax disperser or vortexed with glass beads in RNAPure for up to 10 min in the presence of RNAPure. RNA quality was controlled by gel electrophoresis (12), and RNA concentrations were measured by absorbance at 260 nm (1 unit of optical density at 260 nm = 40 μg/ml of H2O based on the extinction coefficient of RNA in H2O). cDNA synthesis was performed with 2 μg of total RNA for culture cells and 20 μg of total RNA for infected organs using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Gibco BRL/Life Technologies, Karlsruhe, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA from infected tissue was further purified with Nucleospin columns (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). Since the numbers of Candida cells varied in the infected tissues and the RNA quality may differ, a first round of PCR was used to amplify the cDNA of the C. albicans EFB1 gene, encoding the elongation factor 1 (25). EFB1 is expressed in living C. albicans cells to a similar extent under all conditions investigated and is therefore a useful internal standard (35, 36). In a second round of PCR, cDNA amounts were used to give approximately the same amount of amplification products for the EFB1 cDNA. The same cDNA amounts were used for the detection of all SAP transcripts. Primers used to amplify EFB1 were located flanking the intron of this gene and were therefore also useful for demonstrating the absence of contaminating genomic DNA (14). Further standard controls included RT-PCR without the addition of reverse transcriptase to prove the absence of contaminating DNA and reactions with genomic DNA templates to prove the efficiency of the PCR.

For PCR detection of transcripts, a modified protocol was used to optimize amplification of different primer sets. Primer melting temperatures were estimated and tested for each primer pair in a gradient PCR cycler with genomic DNA. The cDNA samples were subjected to 30 (for culture cells) or 40 (for tissue) cycles of denaturation for 30 s at 94°C, annealing for 30 s at 50 to 61°C, and extension for 50 s to 1.5 min at 72°C depending on the primer pairs used. Primers which were highly specific for all 10 SAP genes were chosen (Table 2). To ensure that no cross-hybridization of the SAP-specific primers occurred with other SAP genes, primers were also chosen to give PCR products of different lengths. For the semiquantitative analysis of SAP4 to SAP6 expression, a second set of primers (SAP4c and -d, SAP5c and -d, and SAP6c and-d) (Table 2) was used; these had similar GC contents and melting temperatures (60 to 64°C) and produced fragments of similar lengths (600 to 900 bp). During PCR, the PCR product concentration is proportional to that of the starting cDNA as long as product accumulation remains exponential. The point at which exponential accumulation plateaus can be estimated by noting the point at which continued cycles do not produce significantly increased product yields. To ensure that samples from the exponential phase of PCR amplification were examined, we used 20, 25, 30, and 35 cycles and analyzed the products on agarose gels.

TABLE 2.

PCR primers used for expression analysis

| Primer | Sequence | Annealing temp (°C) | Fragment length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAP1a (5′) | TACTTGTGATAAACCTCGTCCTG | 58.9 | |

| SAP1b (3′) | ATCATCATCCAAATCATAAACAAG | 54.2 | 831 |

| SAP2a (5′) | GTTGATTGTCAAGTCACTTATAGTG | 56.1 | |

| SAP2b (3′) | TCTTAGGTCAAGGCAGAAATCTGG | 59.3 | 898 |

| SAP3a (5′) | CAAGTTCTTCAAGTAGTTCTCAAAAT | 56.9 | |

| SAP3b (3′) | CCCTAAGTAAGAGCAGCAATGT | 58.4 | 826 |

| SAP4a (5′) | CCGTTGGTATTGGTGGTGTT | 57.3 | |

| SAP4b (3′) | AGGAACGGAAATCTTGAGG | 54.5 | 532 |

| SAP5a (5′) | CGATGAGACTGGTAGAGATGGTG | 62.4 | |

| SAP5b (3′) | TTCGGAAACAGGAACGGAG | 56.7 | 870 |

| SAP6a (5′) | AAACCAACGAAGCTACCAGAAC | 58.4 | |

| SAP6b (3′) | TAACTTGAGCCATGGAGATTTTC | 57.1 | 605 |

| SAP7a (5′) | TCTTCTTCACTGGAAGCTGC | 57.3 | |

| SAP7b (3′) | AGGAACAACGGCATGGTTATC | 57.9 | 1,199 |

| SAP8a (5′) | TGGCTCAAGGTCTTGCTATC | 54.0 | |

| SAP8b (3′) | CTCTATAAAGTAGAAATACTTGA | 51.7 | 1,163 |

| SAP9a (5′) | CTCAATACTGCCGATGC | 50.8 | |

| SAP9b (3′) | TAAACCAAAACATAGTAGGATA | 52.8 | 738 |

| SAP10a (5′) | GATCTGCTGCTCAAGGTGTATG | 60.3 | |

| SAP10b (3′) | AAGAGTGGCCAAGAGCATCA | 57.3 | 437 |

| SAP4c (5′) | GGTTCCAGATTCAAATGCCG | 60.0 | |

| SAP4d (3′) | CTTTCTATCATCCAAATCGTAG | 60.0 | 855 |

| SAP5c (5′) | TGAGACTGGTAGAGATGGTG | 60.0 | |

| SAP5d (3′) | GGTTTACCACTAGTGTAATATGT | 62.0 | 902 |

| SAP6c (5′) | AAACCAACGAAGCTACCAGAAC | 64.0 | |

| SAP6d (3′) | TAACTTGAGCCATGGAGATTTTC | 64.0 | 605 |

| EFB1a (5′) | AGTCATTGAACGAATTCTTGGCTG | 65.0 | |

| EFB1b (3′) | TTCTTCAACAGCAGCTTGTAAGTC | 65.0 | 564/928 (cDNA/DNA) |

Determination of tissue damage.

To assess tissue damage of parenchymal organs caused by C. albicans strains, the activities of the pancreas and liver marker enzymes alpha amylase (AM) and alanine-aminotransferase (ALT), respectively, in the plasma of infected animals were measured (19). Blood was obtained via cardiac puncture in deep anesthesia with methoxyflurane (Metofane; Janssen-Cilag, Neuss, Germany) and anticoagulated with heparin. Uninfected animals had ALT values of approximately 5 U/liter and AM values of approximately 500 U/liter.

RESULTS

Histology and tissue damage of parenchymal organs infected by C. albicans wild-type and hypha-deficient strains after i.p. infection.

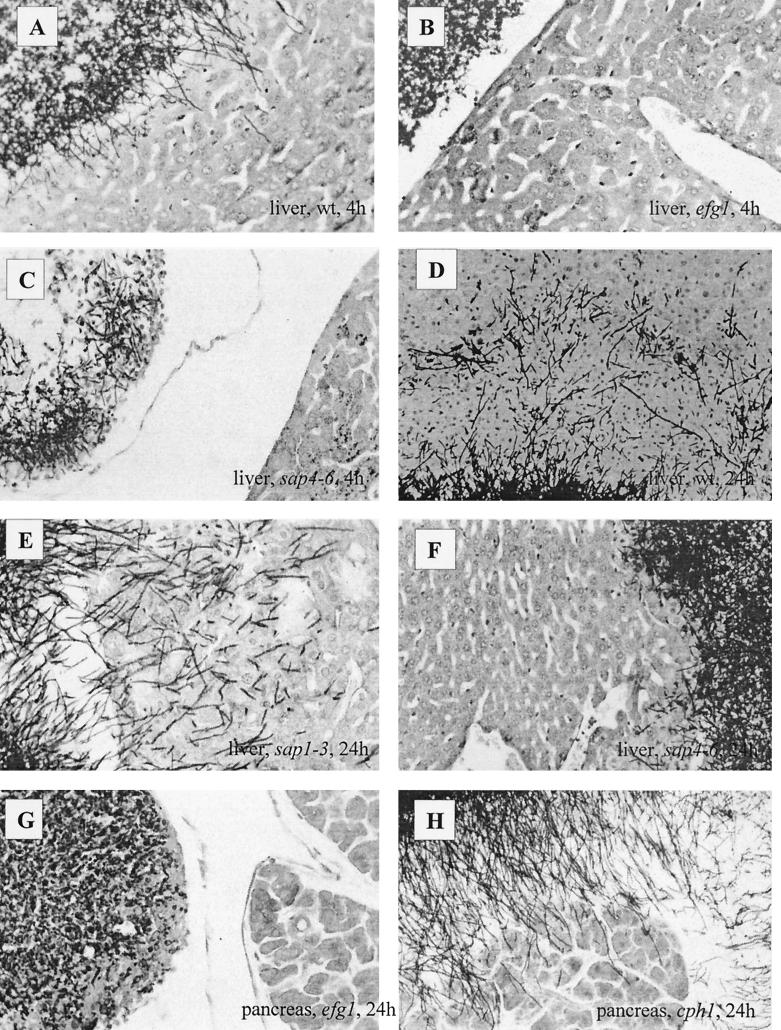

An established intraperitoneal (i.p.) model (19) was used in this study, because invasion of tissue can be visualized histologically at similar time points after injection and tissue damage can be quantified via determination of activity of hepatocyte- and pancreas-specific enzymes. In our hands, this model seemed to be the most appropriate one for investigating the invasion properties of different C. albicans strains, providing results which had the highest level of reproducibility. To study the histology of tissue invaded by wild-type C. albicans cells by light microscopy, parenchymal organs were removed 4 to 48 h after i.p. infection and fixed in phosphate-buffered formaldehyde. Fungi were detected with periodic acid-Schiff staining in paraffin sections (Fig. 1). In addition, electron microscopy was used to study the nature of fungal invasion (Fig. 2). At 4 h after infection, wild-type cells with both yeast and hyphal morphology adhered to parenchymal organs (liver, pancreas, and spleen). However, only some of the hyphal cells penetrated the organs (Fig. 1A). Eight to 24 h after infection massive invasion of all tissues from the intraperitoneal cavity took place with little sign of an inflammatory response (Fig. 1D). Further, more than 90% of the invading cells had a hyphal morphology (Fig. 1 and 2). In later phases of the infection, fungi became encapsulated by inflammatory cells and granulomas and microabscesses were formed. Strongly invading strains such as SC5314 also invaded blood vessels in these phases of the infection and caused systemic distribution (dissemination) following infection of kidneys, heart, and lungs. Few cells also disseminated to the brain.

FIG. 1.

Histology of hypha- and proteinase-deficient C. albicans mutants. Four hours after i.p. infection, wild-type (wt) C. albicans yeast and hyphal cells adhered to and began to invade liver tissue (A), while efg1 mutant yeast cells (B) and sap4 to sap6 yeast and hyphal cells (C) did not invade the tissue after 4 h. At this time point and at later stages, sap4 to sap6 mutant cells appeared to be surrounded by larger amounts of inflammatory cells (granulocytes and macrophages) than the wild-type cells. These cells seemed to inhibit the growth and penetration of the fungal mutant cells more strongly than the wild-type cells. Twenty-four hours after infection, a large number of hyphal cells of the wild type (D) and the sap1 to sap3 mutant (E) deeply penetrated the liver. In contrast, hyphal cells of the sap4 to sap6 mutant poorly invaded the liver (F). No efg1 mutant cells were found close to the liver, and invasion of efg1 mutant cells into the pancreas was completely blocked as noted 24 h after infection (G), while the cph1 mutant (H) showed the same invasive phenotype as the wild type.

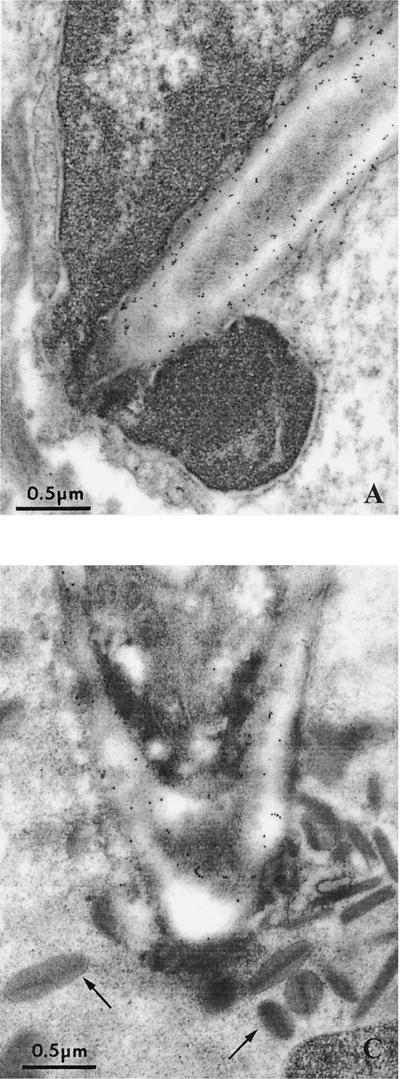

FIG. 2.

C. albicans cells invading host cells and ultralocalization of Sap antigen. Electron microscopy of single C. albicans wild-type cells invading parenchymal tissue. Proteinase antigens were detected by immunogold labeling using Sap1- to Sap3- and Sap4- to Sap6-specific antibodies. (A) Hyphal cell directly penetrating a hepatocyte with Sap1 to Sap3 antigens on the cellular surface. (B) Localization of Sap4 to Sap6 proteinases on an invading hyphal cell (liver, 24 h after i.p. infection). (C) Localization of Sap4 to Sap6 antigens on a hyphal cell penetrating a granulocyte (eosinophil) as identified by typical granulate material (arrows) and morphology (liver, 24 h after i.p. infection).

Since the vast majority of invading wild-type cells had hyphal morphology, we investigated the invasive abilities of mutants which had previously been shown to be hypha deficient under hypha-inducing conditions in vitro in our i.p. model. Mutants lacking the transcriptional factor Cph1 had reduced abilities to produce hyphal cells on solid Spider medium and showed moderately attenuated virulence in an intravenous (i.v.) mouse model (22). In our model of i.p. infection a cph1 mutant still produced long hyphal cells and showed invasive abilities indistinguishable from those of the parental strain SC5314 (Fig. 1; Table 3). This was in contrast to a mutant lacking Efg1 (41), another transcriptional factor which regulates hyphal production. Mutants lacking the EFG1 gene did not produce hyphal cells under most conditions tested and showed strongly reduced virulence in an i.v. mouse model (22). In our model, efg1 mutants had a strongly reduced ability to produce hyphal cells in vivo and did not invade any parenchymal organ (Fig. 1).

TABLE 3.

ALT as an indicator of invasion and tissue damage of liver and tissue burden in mice infected with C. albicans wild type and hypha-deficient mutant cells 24 h after i.p. infectiona

| Strain or genotype | ALT concn (U/liter)

|

Log CFU/organ

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| SC5314 | 685.8 | 31.97 | 5.59 | 0.28 |

| efg1 | 32.2* | 5.76 | 6.65* | 0.15 |

| cph1 | 493.6 | 192.10 | 5.62 | 0.31 |

| efg1/cph1 | 29.4* | 4.50 | 6.43* | 0.18 |

Four (SC5314) or five (mutant strains) animals were tested for each strain. *, significantly different from value for SC5314 (P ≤ 0.05) as determined by Student's t test with corrections according to Bonferroni.

Histological sections of parenchymal organs after i.p. infection of wild-type strains showed that a large number of hyphal cells deeply invaded the tissue and thus caused host cell damage. When host cells of the liver or pancreas were damaged, the organ-specific enzymes AM (pancreas) and ALT (liver) were released and were detectable in the blood. Therefore, we used AM and ALT activities in the blood to monitor the potential of wild-type and mutant C. albicans strains to damage the tissue of the liver and pancreas (Table 3). Wild-type cells caused severe tissue damage, as indicated by high AM and ALT activities (Table 3). In sharp contrast, efg1 mutants were unable to cause tissue damage in the liver (Table 3) or pancreas (data not shown) despite the fact that large numbers of cells attached to these organs (Table 3). Similar data were obtained with a double mutant lacking both Efg1 and Cph1 (Table 3). Mutants lacking Cph1 had only moderately reduced abilities to damage the liver (Table 3) and pancreas (data not shown).

Efg1- and Cph1-deficient mutants have altered profiles of expression of SAP4 to SAP6 under hypha-inducing conditions in vitro.

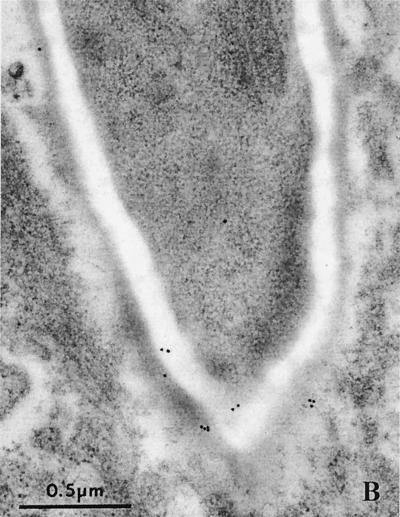

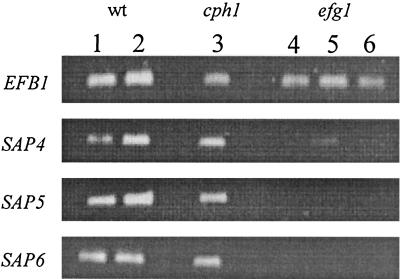

Since the hypha-deficient efg1 mutant was, in contrast to the cph1 mutant, not able to invade or damage tissue, we questioned whether this was due solely to a block in dimorphism or to the loss of factors associated with hyphal cells. The proteinase genes SAP4 to SAP6 have been shown to be regulated during the dimorphic transition (12, 37, 43). Therefore, we investigated the detailed expression of SAP genes in efg1 and cph1 mutants. In both mutants, expression of SAP1 to SAP3 and SAP7 to SAP10 was still detectable and seemed to be unchanged compared to that in wild-type cells under all in vitro conditions investigated (data not shown). In order to investigate how genes are expressed under hypha-inducing conditions, hyphal production in wild-type cells was induced by incubation in 5% serum or by pH- and temperature-regulated transition. Efg1- and Cph1-deficient strains were incubated under the same conditions. After 90 min in serum, >95% of wild-type cells and >95% of cph1 cells produced germ tubes. After 120 min in Lee's medium, >75% of wild-type cells and >50% of cph1 cells produced germ tubes, while no germ tubes were detected for the efg1 mutant at any time in both media. When cph1 mutants were incubated in liquid Lee's medium under hypha-inducing conditions (pH and temperature shift), fewer hyphal cells were produced than in the wild type; however, expression of SAP5 and SAP6 was found to be notably enhanced under these conditions (Fig. 3). During incubation in serum-containing medium, the expression pattern was similar to that of the wild type. In contrast, the efg1 mutant failed to produce any hyphal cells and had enhanced expression of SAP4 to SAP6 in Lee's medium but strongly reduced levels of SAP4 to SAP6 transcripts in medium containing serum. Therefore, SAP4 to SAP6 expression is not necessarily linked to hyphal morphology but is regulated by factors which also regulate hyphal formation. These data also suggest that hyphal cells may require the expression of hypha-associated SAP genes during invasion. Therefore, we investigated the expression of SAP genes during i.p. infection.

FIG. 3.

SAP4 to SAP6 expression profile pattern of wild-type (wt), cph1, and efg1 strains. Hyphal production in wild-type cells was induced by incubation in 5% serum (A) or by pH- and temperature-regulated transition (B). Cph1- and Efg1-deficient strains were incubated under the same conditions. Samples were collected 10, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min after induction, and total RNA was isolated. RT-PCR was used to amplify SAP4- to SAP6-specific transcripts as described in Materials and Methods. Only the results from 25 (A) and 30 (B) cycles are shown. EFB1 primers were used as an internal control and to show the absence of contaminating genomic DNA (30 cycles) (14, 35, 36). The notably reduced level of SAP4 to SAP6 expression by the efg1 mutant observed during serum induction (A) was also observed with 30 PCR cycles. Both cph1 and efg1 mutants had enhanced levels of SAP4 to SAP6 transcripts during pH- and temperature-regulated transition (B). Since the 30-min sample of the cph1 mutant in panel A showed only a weak signal for EFB1 expression due to technical reasons, the possibility that SAP4 to SAP6 were expressed at this time point cannot be excluded.

Expression of SAP genes during i.p. infection.

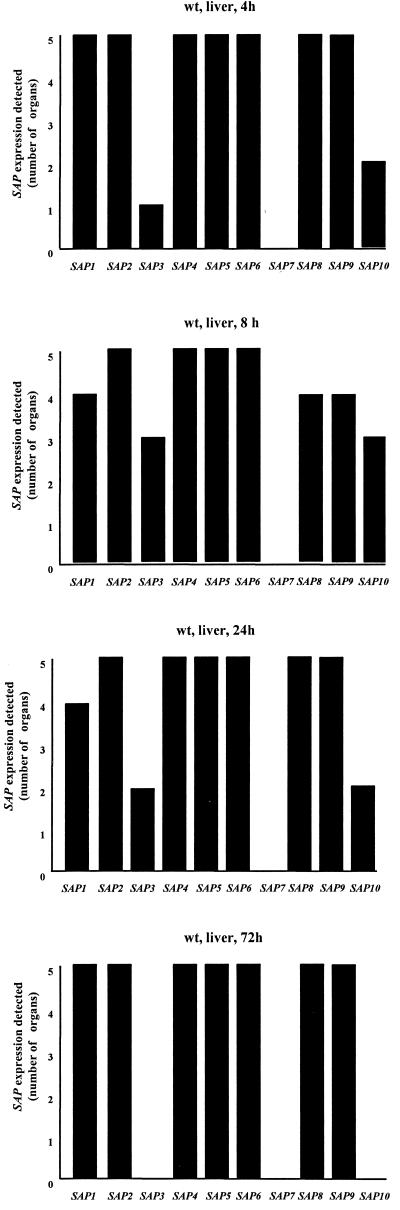

To study the expression of the C. albicans SAP gene family during i.p. infections, SC5314 cells were grown in complex medium and washed with phosphate-buffered saline prior to injection into the peritoneal cavity. Mice were infected with 108 cells/mouse, and organs were removed 4, 8, 24, and 72 h later. Regions of the organs where invasion took place or where the fungi adhered were excised and divided in two parts of comparable size. In one half of the sample the number of infecting cells (CFU per organ; Table 3) was determined, while the remaining tissue was shock frozen or fixed with formaldehyde and used for RT-PCR or histology, respectively (Fig. 1 and 4). The respective regions could be easily identified macroscopically as plaques on the surface of the organs. At least five organs were investigated for each time point. Four hours after injection, Candida cells had attached to the surfaces of parenchymal organs (Fig. 1) and expressed SAP1, SAP2, SAP4 to SAP6, SAP8, and SAP9 in all infected livers (Fig. 4). Four hours later, fewer animal samples had detectable transcripts of SAP1 and SAP8, while slightly more SAP3 and SAP10 signals were found in liver tissue (Fig. 4). Twenty-four hours after injection, transcripts of SAP2, SAP4 to SAP6, SAP8, and SAP9 were again detected in all liver tissue samples (Fig. 4). During this period, invasion by Candida cells was most pronounced (Fig. 1). Three days after infection, expression of SAP1, SAP2, SAP4 to SAP6, SAP8, and SAP9 was detected in all samples (Fig. 4). In contrast, no transcripts of SAP3 and SAP10 were detected. Transcripts of SAP7 were not detectable at any time point.

FIG.4.

In vivo expression of the SAP gene family in infected liver during i.p. infections. Mice were infected i.p. with 108 cells/mouse, and organs were removed. Total RNA from each organ sample was used for RT-PCR detection of SAP transcripts as described in Materials and Methods. At least five organs were investigated at each time point. wt, wild type.

Ultralocalization of Sap proteins in infected tissue.

To show that in vivo-expressed SAP genes were translated into the corresponding proteins and to demonstrate the ultralocalization of proteinase antigens during infection, we used immunoelectron microscopy. Infected tissue was incubated with Sap1- to Sap3-specific or Sap4- to Sap6-specific antibodies (1) (Fig. 2). Strong expression of Sap1 to Sap3 antigens was detected on the surface of both yeast and hyphal cells. In contrast, lower numbers of Sap4 to Sap6 antigens were found mostly (>90%) on the surface of hyphal cells. However, larger numbers of Sap4 to Sap6 antigens were detected on those Candida hyphal cells which penetrated host cells or blood vessels or were intracellular or in direct contact with damaged host cells (Fig. 2). This was most pronounced in Candida cells within eosinophils. To quantify Sap antigen expression, gold particles were counted in 10 randomly chosen cells for Sap1 to Sap3 and for Sap4 to Sap6. In addition, we counted the number of Sap4- to Sap6-labeled C. albicans cells in contact with eosinophils and within blood vessels. For the Sap1 to Sap3 antibody we found 242 ± 139 (mean ± standard deviation) intracellular particles in 10 randomly chosen cells. For the Sap4 to Sap6 antibody we found 17 ± 6 particles for randomly chosen cells and 143 ± 79 particles for the cells which were in close contact with eosinophils or within blood vessels.

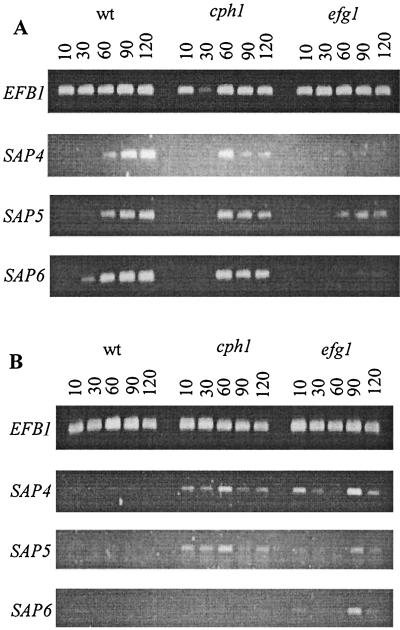

SAP expression profile of hypha-deficient mutants in vivo.

The expression of SAP4 to SAP6 was altered in the efg1 mutant under hypha-inducing conditions in vitro compared to wild-type cells and the cph1 mutant. This was clearest in serum-containing medium, where the level of SAP4 to SAP6 transcripts was strongly reduced. To determine whether the efg1 mutant also had reduced levels of SAP4 to SAP6 transcripts in vivo, we analyzed the expression of these genes in tissue from mice infected with the efg1 and the cph1 mutant. Twenty-four hours after inoculation into the peritoneal cavity, both mutants were able to express all SAP genes (data not shown). However, efg1 mutants had strongly reduced levels of SAP4 to SAP6 transcripts (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

In vivo expression of SAP4 to SAP6 in hypha-deficient mutants. Mice were infected i.p. with 108 cells/mouse, and livers were removed. Total RNA from each liver sample was used for RT-PCR detection of SAP transcripts. The expression patterns for the wild type (wt) and the cph1 and efg1 mutants 24 h after i.p. injection for SAP4 to SAP6 genes are shown. In comparison to wild-type and cph1 mutant cells, efg1 mutants had strongly reduced levels of SAP4 to SAP6 transcripts. After 35 PCR cycles, no signals for SAP5 or SAP6 and only one weak signal for SAP4 were detectable in three samples. After 40 PCR cycles, mRNA expression of all three genes was detectable but notably reduced in the efg1 mutant compared to the wild type.

SAP4 to SAP6 are required for invasion of parenchymal organs.

In vivo expression analysis showed that SAP4 to SAP6 genes were down-regulated in the efg1 mutant during i.p. infection. Therefore, the reduced expression of these genes may have been responsible for the observed inability of efg1 mutants to penetrate parenchymal organs. To ascertain which genes are required for invasion of these organs, we used SAP-deficient mutants and tested their invasive abilities. Triple mutants lacking SAP1 to SAP3 all invaded tissue just like wild-type cells (Fig. 1). However, both yeast and hyphal cells of a triple mutant lacking SAP4 to SAP6 had strongly reduced abilities to penetrate from the peritoneal cavity into the organs (Fig. 1), suggesting that these genes are required for invasion.

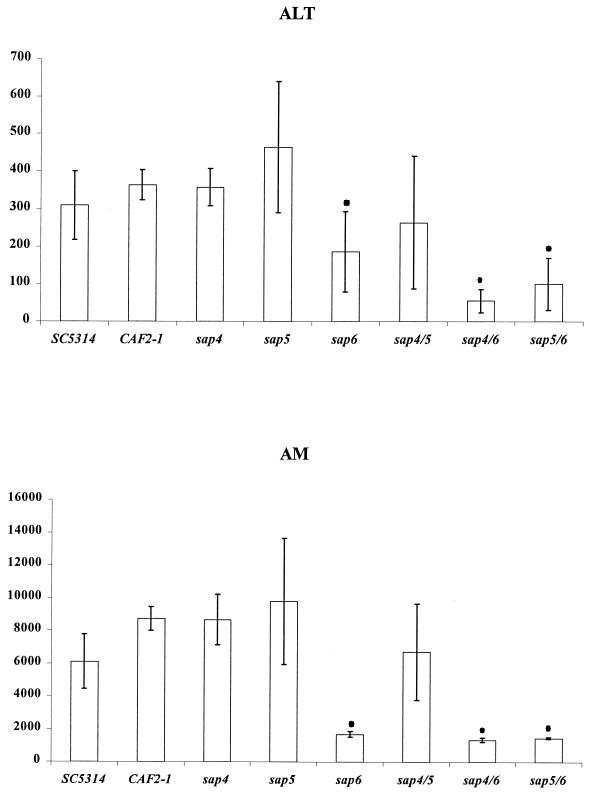

To test which genes of the triple SAP4 to SAP6 mutant were responsible for the observed attenuated invasive properties, we used sap4, sap5, and sap6 single mutants as well as sap4/6, sap5/6, and sap4/5 double mutants and measured the tissue damage of liver and pancreas caused by these mutants (Fig. 6). All mutants were still able to produce hyphal cells to an extent similar to that of the wild type (data not shown). Mutants lacking SAP4 or SAP5 had similar or even higher capabilities to cause tissue damage in both liver and pancreas. This was also the case for the sap4 and -5 double mutant. However, mutants lacking two copies of functional SAP6 had significantly less potential to release the organ marker enzymes, indicating reduced tissue damage. Furthermore, the invasive properties of double mutants lacking SAP6 and SAP4 or SAP6 and SAP5 was further attenuated compared to that of the sap6 single mutant, suggesting a dominant role of Sap6 during invasion and a supporting role for both Sap4 and Sap5 (Fig. 6). In an attempt to restore the invasive properties of wild-type strains, we amplified a 3,213-bp PCR fragment containing the open reading frame and 1,737-bp 5′ and 219-bp 3′ untranslated regions of SAP6 and cloned this fragment into the URA3-carrying integrative vector pCIp10 (28) next to the RP10 region used for integration to give pAF3 (pCIp10-SAP6). pAF3 was transformed into the Ura− sap6 mutant, and Ura+ colonies were tested for growth in minimal medium. Ura+ colonies were further tested for the correct integration of pAF3 at the RP10 locus by Southern analysis and for their ability to express SAP6 by RT-PCR and used for animal infections.

FIG. 6.

Tissue damage cause by C. albicans proteinase-deficient mutants. ALT activity (liver) and AM activity (pancreas) in blood of mice infected with C. albicans wild-type and Sap-deficient mutant cells 24 h after intraperitoneal infection were measured as indicators of invasion and tissue damage of liver and pancreas. Four animals were tested for each strain. Both SC5314 and the URA3/ura3 heterozygote strain CAF2-1, derived from SC5314, were used as wild-type controls. CAF2-1 was not found to be less invasive than SC5314. ∗, significantly different from value for CAF2-1 (P ≤ 0.05) as determined by Student's t test, with corrections according to Bonferroni.

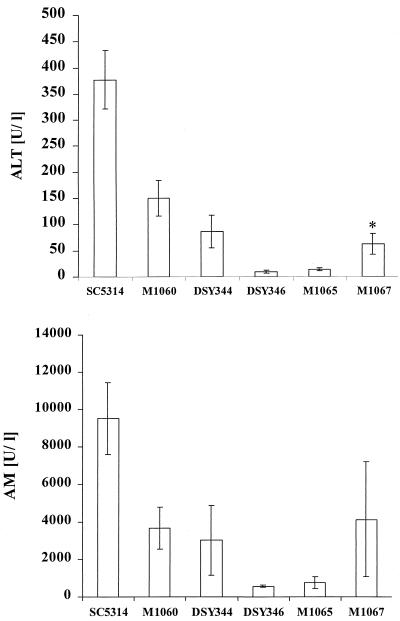

One selected retransformed strain (M1067) had increased invasive properties compared to the Ura+ sap6 null mutant (DSY346) (Fig. 7). However, the restored strain was still strongly reduced in its ability to cause tissue damage (ALT, 62 ± 19.7 U/liter; AM, 4,134.5 ± 3,052.6 U/liter) compared to the wild type, SC5314 (ALT, 377 ± 56 U/liter; AM, 9,530 ± 1,920 U/liter). When the heterozygote SAP6/sap6 mutant (DSY344) was tested, we detected a clear decline in tissue damage (ALT, 86 ± 31 U/liter; AM, 3,026 ± 1,846 U/liter), suggesting that both alleles of SAP6 are necessary for the fully invasive phenotype. In order to clarify if the plasmid construct used also contributed to the reduced invasiveness of M1067, we transformed the Ura− parental strain CAI4 with pCIp10 lacking SAP6 and used this strain for animal infection. Surprisingly, Ura+ transformants carrying pCIp10 only (M1060) also had reduced ALT (150.7 ± 34 U/liter) and AM (3,665 ± 1,117.9 U/liter) values, indicating weak invasiveness compared to the wild-type SC5314. This suggests that integration of pCIp10 at the RP10 locus did not restore full virulence of Ura− wild-type strains in our model of i.p. infection and that the weak invasiveness of the retransformant was due to a gene dosage effect of both SAP6 and the URA3 marker.

FIG. 7.

Invasiveness of the SAP6/sap6 heterozygote mutant, control strains, and a transformant carrying a SAP6-containing plasmid (pAF3). Tissue damage of liver and pancreas was investigated as described for Fig. 6 with the following strains: SC5314 (SAP6/SAP6), M1060 (CAI4 with pCIp10), DSY344 (SAP6/sap6), DSY346 (sap6/sap6), M1065 (sap6/sap6 with pCIp10), and M1067 (sap6/sap6 with pAF3). Four animals were tested for each strain except for M1060, M1065, and M1067 for AM (two animals each). ∗, significantly different from value for M1065 (P ≤ 0.05) as determined by Student's t test, with corrections according to Bonferroni.

DISCUSSION

Although both yeast and hyphal cells of C. albicans are found in infected host tissues, it is widely believed that hyphal formation is important for the invasive properties of the fungus. A number of mutants which lack regulatory elements necessary for hyphal formation have been described (2, 6). However, the defined function of hyphal formation and the reason why hypha-deficient mutants are avirulent are still not clear. There are several possible hypha-specific traits that may be important for a full-virulence phenotype. For example, it is known that the surfaces of hyphal cells contain specific adhesion molecules which are absent or are not exposed on yeast surfaces (8). Thigmotropism (contact sensing) and physical forces of Candida hyphal cells are possible aids for epithelial penetration (38). Furthermore, hyphal formation may assist the fungus to escape from macrophages or endothelial cells after phagocytosis (23, 32, 44). During invasion of host cell tissue and during escape of host cells that have internalized the fungus, hypha-associated factors such as secreted hydrolases may be crucial. Three of the ten members of the secreted aspartic proteinase gene (SAP gene) family, SAP4 to SAP6, were previously shown to be hypha associated (12, 43) and may thus be important for the invasive properties of C. albicans hyphal cells. Therefore, we studied the expression pattern and role of the SAP gene family during an intraperitoneal infection and investigated whether the reduced virulence of hypha-deficient mutants may be due to a reduced or modified expression of hypha-associated SAP genes.

Transcriptional factors that regulate the yeast-to-hypha transition, such as Efg1 and Cph1, may affect multiple genes (17, 22). For example, Lo et al. (22) suggested that it is possible that genes unrelated to cell shape but regulated by the transcription factors Cph1 and Efg1 are required for virulence. Using Northern blot analysis, Schröppel et al. (37) found that expression of SAP4 to SAP6 was undetectable in efg1 mutants in serum-containing medium, which is a strong environmental signal for hyphal growth of wild-type cells. Using RT-PCR, we were able to confirm reduced expression of SAP4, SAP5, and SAP6 in the efg1 mutant under such conditions. However, expression of all three genes was even enhanced in both efg1 and cph1 mutants when hyphal formation was induced via a pH and temperature shift protocol, suggesting that the transcription factors Efg1 and Cph1 can be either positive or negative regulators of SAP4 to SAP6 expression depending on the environmental signals. Since efg1 mutants do not produce hyphal cells under these conditions, it can also be concluded that expression of SAP4 to SAP6 is not strictly linked to the hyphal morphology but regulated by a factor which also regulates hyphal formation.

To study whether modification of the proteinase expression pattern may be responsible for the reduced-virulence phenotype of hyphal mutants (22, 41), we investigated the expression of the SAP gene family in the wild type and hypha-deficient mutants during i.p. infection and parenchymal tissue invasion. Expression of Sap antigen during systemic infections has long been recognized in antigen-antibody studies (24, 33). Recently, Staib et al. (40) demonstrated a high expression of SAP5 in all phases of an i.p. infection with wild-type cells and a late induction of SAP2 and SAP6 using in vivo expression technology. Using the more sensitive RT-PCR technology, we found that SAP1, SAP2, SAP4 to SAP6, and SAP9 transcripts were detectable at all time points investigated during the same type of infection with wild-type cells. Mutants lacking Cph1 produced invading hyphae and had a similar pattern of SAP expression. In contrast, Efg1-deficient mutants did not produce hyphal cells and had strongly reduced levels of SAP4 to SAP6 transcripts similar to the expression pattern observed in serum-containing medium. With Sap-specific antibodies, Sap1 to Sap3 proteinases were detected on both yeast and hyphal wild-type cells, while the Sap4- to Sap6-specific antigen was identified mostly on penetrating hyphal cells, confirming hypha-specific expression of Sap4 to Sap6.

Although expression of SAP2 was high in all in vivo samples investigated and large amounts of Sap1 to Sap3 antigens were found on all types of wild-type Candida cells, the level of expression did not correlate with the importance of the corresponding gene for invasion. Only mutants lacking SAP6 had strongly reduced abilities to invade and damage parenchymal organs despite the fact that hyphal production was normal and all other proteinase genes were still expressed. Transformation with a plasmid containing the native SAP6 gene (pAF3) increased the invasive properties of the sap6 mutants, showing that the reduced-virulence properties of the sap6 mutants was indeed due to disruption of SAP6. The fact that the plasmid did not restore the full virulence phenotype is likely due to a gene dosage and position effect of both the URA3 marker and SAP6, since the Ura− parental strain CAI4 transformed with the plasmid lacking SAP6 (pCIp10) and, to an even greater extent, the SAP6/sap6 heterozygote mutant also had strongly reduced abilities to cause tissue damage. An attenuation of URA3 gene expression due to integration of the URA3 gene into a nonnative locus was also reported by Lay et al. (21).

Our results are in agreement with the finding that sap4 to sap6 mutants are strongly attenuated in an i.v. model of systemic infection (34). Kretschmar et al. (19) found that in contrast to wild-type cells, the attenuated ability of the sap4 to sap6 mutant to penetrate host tissue could not be reduced further by the addition of the aspartic proteinase inhibitor pepstatin A.

In addition, Borg von-Zepelin et al. (1) demonstrated that Sap4 to Sap6 are highly expressed on Candida hyphal forms after phagocytosis by macrophages and that these proteinases play a crucial role in the survival of the fungus within the macrophages. These findings in conjunction with our data suggest that hypha-specific proteinases, Sap6 in particular, play a dominant role during systemic infections by aiding penetration of tissue and survival of the fungus in phagocytes. In sharp contrast, sap4 to sap6 mutants showed a virulence phenotype during mucosal infections indistinguishable from wild-type cells supporting the view that distinct proteinases of the Sap isoenzyme family have distinct functions during the different types and stages of infection (5, 15, 36). Interestingly, sap4 to sap6 mutants which had invaded parenchymal tissue appeared to be surrounded by more inflammatory cells than wild-type cells were (Fig. 1), making it possible that an additional function of Sap4 to Sap6 may also be to counteract immunoactive cells of the host. Recently, Phan et al. (32) demonstrated a reduced capacity for efg1 mutants to invade and injure endothelial cells. Those authors concluded that Efg1 contributes to virulence by regulating hyphal formation and factors that enable C. albicans to invade endothelial cells. We propose here that one of these factors is the hypha-associated proteinases Sap4 to Sap6.

It should be noted that the reduced invasive properties and the reduced tissue damage of the efg1 mutant in our model are unlikely to be influenced by reduced cell growth or enhanced elimination of the cells in the peritoneal cavity, since high numbers of CFU were recovered from these organs within the first 24 h of infection.

In summary, these data demonstrate that strains lacking factors that regulate both hyphal and proteinase Sap4 to Sap6 production are noninvasive. However, strains that still produce hyphal cells but lack hypha-associated proteinases are also less invasive. Therefore, it is not the hyphal morphology alone which makes the fungus invasive; it is also the activity of distinct hypha-associated factors. In addition, our data suggest that distinct SAP proteinase genes are expressed during intraperitoneal infection by C. albicans, with a prominent role for Sap6 in invasion of parenchymal organs.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Januschke, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, Germany, for excellent technical assistance, M. Monod, Universitaire Vaudoise, Lausanne, Switzerland, and M. Borg-von Zepelin, University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany, for providing the Sap-specific polyclonal antibodies, J. Ernst, University of Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany, and G. Fink, Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Cambridge, Mass., for providing the hypha-deficient efg1, cph1, and efg1/cph1 mutants, A. J. Brown, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, United Kingdom, for providing pCIp10, and C. Westwater, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grants Hu528/8, KO1106/4-1, and KR2002/1-1) and the European Commission (QLK2-2000-00795).

Editor: T. R. Kozel

REFERENCES

- 1.Borg-von Zepelin, M., S. Beggah, K. Boggian, D. Sanglard, and M. Monod. 1998. The expression of the secreted aspartic proteinases Sap4 to Sap6 from Candida albicans in murine macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 28:543-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown, A. J., and N. A. Gow. 1999. Regulatory networks controlling Candida albicans morphogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 7:333-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buffo, J., M. A. Herman, and D. R. Soll. 1984. A characterization of pH-regulated dimorphism in Candida albicans. Mycopathologia 85:21-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cutler, J. E. 1991. Putative virulence factors of Candida albicans. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 45:187-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Bernardis, F., S. Arancia, L. Morelli, B. Hube, D. Sanglard, W. Schäfer, and A. Cassone. 1999. Evidence that members of the secretory aspartic proteinase gene family, in particular SAP2, are virulence factors for Candida vaginitis. J. Infect. Dis. 179:201-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ernst, J. F. 2000. Transcription factors in Candida albicans--environmental control of morphogenesis. Microbiology 146:1763-1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fonzi, W. A., and M. Y. Irwin. 1993. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics 134:717-728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gale, C. A., C. M. Bendel, M. McClellan, M. Hauser, J. M. Becker, J. Berman, and M. K. Hostetter. 1998. Linkage of adhesion, filamentous growth, and virulence in Candida albicans to a single gene, INT1. Science 279:1355-1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillum, A. M., E. Y. H. Tsay, and D. R. Kirsch. 1984. Isolation of the Candida albicans gene for orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase by complementation of S. cerevisiae ura3 and E. coli pyrF mutations. Mol. Gen. Genet. 198:179-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gow, N. A., and G. W. Gooday. 1982. Growth kinetics and morphology of colonies of the filamentous form of Candida albicans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 128:2187-2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoyer, L. L. 2001. The ALS gene family of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol. 9:176-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hube, B., M. Monod, D. A. Schofield, A. J. P. Brown, and N. A. R. Gow. 1994. Expression of seven members of the gene family encoding secretory aspartyl proteinases in Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 14:87-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hube, B., D. Sanglard, F. C. Odds, D. Hess, M. Monod, W. Schäfer, A. J. Brown, and N. A. Gow. 1997. Disruption of each of the secreted aspartic proteinase genes SAP1, SAP2, and SAP3 of Candida albicans attenuates virulence. Infect. Immun. 65:3529-3538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hube, B., F. Stehr, M. Bossenz, A. Mazur, M. Kretschmar, and W. Schäfer. 2000. Secreted lipases of Candida albicans: cloning, characterisation and expression analysis of a new gene family with at least ten members. Arch. Microbiol. 174:362-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hube, B., and J. Naglik. 2001. Candida albicans proteinases: resolving the mystery of a gene family. Microbiology 147:1997-2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ibrahim, A. S., F. Mirbod, S. G. Filler, Y. Banno, G. T. Cole, Y. Kitajima, J. E. Edwards, Jr., Y. Nozawa, and M. A. Ghannoum. 1995. Evidence implicating phospholipase as a virulence factor of Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 63:1993-1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi, S. D., and J. E. Cutler. 1998. Candida albicans hyphal formation and virulence: is there a clearly defined role? Trends Microbiol. 6:92-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koelsch, G., J. Tang, J. A. Loy, M. Monod, K. Jackson, S. I. Foundling, and X. Lin. 2000. Enzymic characteristics of secreted aspartic proteases of Candida albicans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1480:117-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kretschmar, M., B. Hube, T. Bertsch, D. Sanglard, R. Merker, M. Schröder, H. Hof, and T. Nichterlein. 1999. Germ tubes and proteinase activity contribute to virulence of Candida albicans in murine peritonitis. Infect. Immun. 67:6637-6642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kretschmar, M., A. Felk, P. Staib, M. Schaller, D. Heβ, M. Callapina, J. Morschhäuser, W. Schäfer, H. C. Korting, H. Hof, B. Hube, and T. Nichterlein. 2002. Individual acid aspartic proteinases (Saps) 1-6 of Candida albicans are not essential for invasion and colonisation of the gastrointestinal tract in mice. Microb. Pathog. 32:61-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lay, J., L. K. Henry, J. Clifford, Y. Koltin, C. E. Bulawa, and J. M. Becker. 1998. Altered expression of selectable marker URA3 in gene-disrupted Candida albicans strains complicates interpretation of virulence studies. Infect. Immun 66:5301-5306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lo, H. J., J. R. Köhler, B. DiDomenico, D. Loebenberg, A. Cacciapuoti, and G. R. Fink. 1997. Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell 90:939-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lorenz, M. C., and G. R. Fink. 2001. The glyoxylate cycle is required for fungal virulence. Nature 412:83-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macdonald, F., and F. C. Odds. 1980. Purified Candida albicans proteinase in the serological diagnosis of systemic candidosis. JAMA 243:2409-2411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maneu, V., A. M. Cervera, J. P. Martinez, and D. Gozalbo. 1996. Molecular cloning and characterization of a Candida albicans gene (EFB1) coding for the elongation factor EF-1 beta. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 145:157-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monod, M., G. Togni, B. Hube, and D. Sanglard. 1994. Multiplicity of genes encoding secreted aspartic proteinases in Candida species. Mol. Microbiol. 13:357-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monod, M., B. Hube, D. Hess, and D. Sanglard. 1998. Differential regulation of SAP8 and SAP9, which encode two new members of the secreted aspartic proteinase family in Candida albicans. Microbiology 144:2731-2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murad, A. M., P. R. Lee, I. D. Broadbent, C. J. Barelle, and A. J. Brown. 2000. CIp10, an efficient and convenient integrating vector for Candida albicans. Yeast 16:325-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naglik, J. R., G. Newport, T. C. White, L. L. Fernandes-Naglik, J. S. Greenspan, D. Greenspan, S. P. Sweet, S. J. Challacombe, and N. Agabian. 1999. In vivo analysis of secreted aspartic proteinase expression in human oral candidiasis. Infect. Immun. 67:2482-2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Odds, F. C. 1988. Candida and candidosis, 2nd ed. Baillière Tindall, London, United Kingdom.

- 31.Odds, F. C. 1994. Candida species and virulence. ASM News 60:313-318. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phan, Q. T., P. H. Belanger, and S. G. Filler. 2000. Role of hyphal formation in interactions of Candida albicans with endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 68:3485-3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rüchel, R., F. Zimmermann, B. Böning-Stutzer, and U. Helmchen. 1991. Candidiasis visualised by proteinase-directed immunofluorescence. Virchows Arch. A 419:199-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanglard, D., B. Hube, M. Monod, F. C. Odds, and N. A. Gow. 1997. A triple deletion of the secreted aspartic proteinase genes SAP4, SAP5, and SAP6 of Candida albicans causes attenuated virulence. Infect. Immun. 65:3539-3546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaller, M., W. Schafer, H. C. Korting, and B. Hube. 1998. Differential expression of secreted aspartyl proteinases in a model of human oral candidosis and in patient samples from the oral cavity. Mol. Microbiol. 29:605-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaller, M., H. C. Korting, W. Schäfer, J. Bastert, W. Chen, and B. Hube. 1999. Secreted aspartic proteinase (Sap) activity contributes to tissue damage in a model of human oral candidiasis. Mol. Microbiol. 34:169-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schröppel, K., K. Sprosser, M. Whiteway, D. Y. Thomas, M. Röllinghoff, and C. Csank. 2000. Repression of hyphal proteinase expression by the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase phosphatase Cpp1p of Candida albicans is independent of the MAP kinase Cek1p. Infect. Immun. 68:7159-7161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sherwood, J., N. A. Gow, G. W. Gooday, D. W. Gregory, and D. Marshall. 1992. Contact sensing in Candida albicans: a possible aid to epithelial penetration. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 30:461-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soll, D. R. 1997. Gene regulation during high-frequency switching in Candida albicans. Microbiology 143:279-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Staib, P., M. Kretschmar, T. Nichterlein, H. Hof, and J. Morschhäuser. 2000. Differential activation of a Candida albicans virulence gene family during infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6102-6107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stoldt, V. R., A. Sonneborn, C. E. Leuker, and J. F. Ernst. 1997. Efg1p, an essential regulator of morphogenesis of the human pathogen Candida albicans, is a member of a conserved class of bHLH proteins regulating morphogenetic processes in fungi. EMBO J. 16:1982-1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sundstrom, P. 1999. Adhesins in Candida albicans. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:353-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White, T. C., and N. Agabian. 1995. Candida albicans secreted aspartyl proteinases: isoenzyme pattern is determined by cell type, and levels are determined by environmental factors. J. Bacteriol. 177:5215-5221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zink, S., T. Nass, P. Rosen, and J. F. Ernst. 1996. Migration of the fungal pathogen Candida albicans across endothelial monolayers. Infect. Immun. 64:5085-5091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]