Abstract

Shigella flexneri infection of human macrophages is followed by rapid bacterial escape into the cytosol and secretion of IpaB, which activates caspase-1 to mediate cell death and release of mature interleukin (IL)-1β. Here we report a different outcome following infection of human peripheral blood monocytes. S. flexneri infects monocytes inefficiently in the absence of complement and, following complement-dependent uptake, cannot escape the endosomal compartment. Consequently, bacteria are killed within the first 60 min in the absence of monocyte cell death, as demonstrated by immunofluorescence and electron microscopy and enumeration of colonies in a gentamicin protection assay. Despite early bacterial death, wild-type S. flexneri influenced the subsequent monocyte proinflammatory cytokine response and cell fate. Infection with wild-type S. flexneri resulted in IpaB-dependent suppression of IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and IL-6 compared with that of plasmid-cured avirulent S. flexneri-infected cells. Furthermore, over the following 6 to 8 h, virulent S. flexneri-infected monocytes died by apoptosis whereas avirulent infected monocytes died by necrosis. Together, these results imply that monocytes migrating into the inflammatory site during the early stages of shigellosis kill S. flexneri but that during bacterial uptake, they receive virulence signals from S. flexneri which induce delayed apoptosis associated with suppression of the proinflammatory cytokine response to bacterial phagocytosis. This delayed apoptosis may have important effects on the ordered initiation of the innate immune response, leading to the excessive inflammatory response characteristic of shigellosis.

Shigellosis, or bacterial dysentery, is a highly contagious and severe inflammatory diarrhea caused by bacteria of the genus Shigella, of which S. flexneri is the predominant species responsible for endemic disease. Each year there are about 160 million cases of shigellosis resulting in more than one million deaths, the majority of which are those of young children in the developing world (22). Shigella causes disease by invading the colonic and rectal mucosa via the antigen uptake mechanism of epithelial M cells, allowing the bacteria to be delivered to the subepithelial dome overlying intestinal lymphoid follicles (44). Shigella can then enter adjacent epithelial cells via their basolateral surface through activity of the invasion plasmid antigens (Ipa) B, C, and D, which are secreted onto the epithelial cell surface by a Type III secretion system (27). Following invasion, they lyse the endocytic vacuole to access the cytosol, where they proliferate and migrate from cell to cell through an actin-based motility mechanism (5). Intestinal epithelial cells are likely to be the desired intracellular niche for Shigella, where they are protected from the innate and humoral components of the immune system. However, prior to epithelial cell invasion, Shigella can be phagocytosed by resident tissue macrophages. It is generally considered that macrophages take up wild-type Shigella via host cell phagocytic mechanisms, although there is evidence that uptake can be increased by activity of the Shigella Ipa proteins (23). In vitro studies have shown that entry into macrophages is followed by rapid IpaB-, IpaC-, and IpaD-dependent escape from the phagosome into the cytosol, where IpaB binds and activates caspase-1 (17) to initiate rapid apoptotic cell death via an ill-defined mechanism (16, 46). Apoptotic cells have been found in vivo in the lymphoid follicles of rabbit ileal loops infected with S. flexneri (47) and in rectal mucosal biopsies of people with shigellosis (20), supporting the conclusion that macrophage cell death occurs during natural infection.

Caspase-1 is also known as the interleukin-1 (IL-1)-converting enzyme, due to its ability to cleave pro-IL-1β (42) and the related cytokine pro-IL-18 (2) into their mature active forms. IpaB-activated caspase-1 can cleave these two cytokines, which are then released from the dying macrophage. There is good evidence from animal models that macrophage-derived IL-1β, in concert with IL-8 released from infected epithelial cells, contributes towards the stimulation of the massive inflammatory response characteristic of shigellosis (36, 37). Although the intense neutrophil influx leads to clinical symptoms and tissue destruction (32), neutrophils can phagocytose and efficiently kill Shigella within the phagocytic vacuole (26), thus helping to localize infection to the mucosa and prevent deeper tissue invasion and systemic spread (37).

The outcome following uptake of Shigella by monocytes has not been thoroughly examined. Within 2 to 4 h of infection, an increased concentration of mononuclear phagocytes can be seen under the follicle-associated epithelium adjacent to the invading Shigella (3). It is highly likely that a majority of these cells are newly infiltrating monocytes. It has been known for a number of years that monocytes and infiltrating phagocytic cells (8, 9) have a greater microbicidal capacity than resident macrophages, and indeed, the in vitro microbicidal capacity of freshly isolated monocytes is similar to that of neutrophils (41). It is therefore relevant to consider whether phagocytosis of S. flexneri by monocytes has a different outcome from that seen with macrophages. Here we show that monocytes isolated from human peripheral blood can kill opsonized Shigella within the phagocytic vacuole. However, this killing is followed by IpaB-dependent suppression of the proinflammatory cytokine production associated with induction of apoptosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

M90T is a wild-type virulent strain of S. flexneri serotype 5a, and BS176 is a plasmid-cured avirulent derivative of M90T (38). The construction of a nonpolar IpaB deletion mutant from M90T has been previously described (27). The Escherichia coli K12 strain was obtained from Public Health Laboratory Service, London, United Kingdom. Bacteria were grown overnight in Trypticase soy broth (TSB) at 37°C on a rotating wheel and then subcultured (1:25 dilution) and grown to late-log phase over 2 to 3 h at 37°C prior to use.

Isolation of monocytes and preparation of monocyte-derived macrophages.

Monocytes were isolated from fresh citrated venous blood obtained from healthy donors, which had been diluted 1:1 with magnesium and calcium-free Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) (Sigma) by centrifugation over Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia) for 20 min at 650 × g at room temperature. Cells at the interface were collected, washed three times, resuspended in RPMI medium (Sigma), counted in a hemocytometer, and then allowed to adhere to 24-well tissue culture plates (Techno Plastic Products, Trasadingen, Switzerland) for 1 h at 37°C to obtain a density of 0.5 × 106 monocytes per well. Nonadherent cells were removed by washing twice with RPMI medium, resulting in a cell monolayer consisting of between 70 and 90% monocytes, as assessed by counting Giemsa-stained cells adherent to coverslips processed in parallel. To obtain monocyte-derived macrophages (referred to as macrophages in this paper), monocytes were isolated as described above but were added to plates at a density of 0.25 × 106 monocytes per well, allowed to adhere, washed, and then cultured in RPMI medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (PAA Laboratories, Somerset, United Kingdom) and 10 ng of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (R&D Systems)/ml. After 3 days, the cells were washed twice and cultured in RPMI medium with 10% fetal calf serum and without granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and used for infection studies after a further 4 to 7 days.

Infection of monocytes and macrophages with S. flexneri.

Monocyte and macrophage monolayers were incubated with unopsonized S. flexneri at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of between 5 and 25 bacteria per cell. Bacteria were centrifuged onto cells at 650 × g for 5 min to bring the bacteria into close contact with the cells for synchronized uptake and incubated for 40 min prior to addition of gentamicin (final concentration, 50 μg/ml) to halt infection and kill extracellular bacteria. Supernatants were collected at the indicated times postinfection to assess cell cytotoxicity. The number of live intracellular bacteria within cells that retained an intact cell membrane was assessed using the gentamicin protection assay. Briefly, supernatants were removed after a further 80 min culture with gentamicin, and adherent cells were lysed for 5 min with 0.5% sodium deoxycholate (Sigma) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to release the intracellular bacteria. Lysates were serially diluted in TSB and spread on TSB agar plates, and CFU were counted after overnight incubation at 37°C. Bacteria were opsonized by incubation at an optical density (at 600 nm) of 0.5 in RPMI medium containing 6% human serum for 30 min at 37°C. S. flexneri was resistant to complement-dependent killing at this concentration, as assessed by CFU counting and as previously reported (19). In preliminary experiments it was noted that human serum caused agglutination of S. flexneri but not of other gram-negative bacteria such as E. coli and Salmonella dublin (data not shown). Bacterial agglutination inhibited contact and uniform phagocytosis of S. flexneri. The degree of agglutination varied depending on the human source; hence, serum samples were used from laboratory personnel causing the least agglutination. Opsonized bacteria were centrifuged onto monocytes at an MOI of 5 bacteria per cell unless otherwise indicated. After 40 min of incubation, either gentamicin was added directly to the wells or cells were washed to remove extracellular bacteria prior to the addition of gentamicin. Results obtained were identical for both treatments. Infected cells and supernatants were processed at the indicated times postinfection for microscopy, cell death assays, and assessment of cytokine synthesis and secretion. In some experiments, monocytes were incubated with 100 μM Ac-Tyr-Val-Ala-Asp (Ome)-CH2F (YVAD) (R&D Systems) prior to infection with S. flexneri.

Detection of S. flexneri-mediated cytotoxicity.

Cytotoxicity was assessed by measuring the release of cytosolic lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) into the supernatant, which reflects loss of plasma membrane integrity in infected cells, and by the production of cytoplasmic mono- and oligonucleosomal DNA fragments bound to core histones, which are produced during apoptotic DNA fragmentation (6). LDH levels were measured using the colorimetric Cytotox 96 kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The percentage of cytotoxicity was calculated as 100 × [(experimental release − spontaneous release)/(total release − spontaneous release)], where spontaneous release is the amount of LDH activity in the supernatant of uninfected cells and total release is the activity in cell lysates. Nucleosomal DNA consisting of DNA-histone complex fragments was measured in cytoplasmic cell extracts by using the quantitative cell death detection enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) Plus assay according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche). Briefly, infected and uninfected monocytes were lysed in Triton X-100 at various times postinfection, and postnuclear supernatants were incubated in streptavidin-coated 96-well ELISA plate wells supplied by the manufacturer. A mixture of a biotin-labeled anti-histone antibody and a peroxidase-labeled anti-DNA antibody was then added to the wells for 2 h. After washing to remove unbound antibodies, the bound peroxidase activity was measured by the addition of ABTS substrate and the color change was read at 405 nm in an automated plate reader. Results are presented as the severalfold increase in cytoplasmic nucleosomal DNA, obtained by dividing the value obtained for infected cells by the background level value obtained from lysis of uninfected cells.

Labeling of intracellular S. flexneri for fluorescence microscopy.

Freshly isolated monocytes were adhered to glass coverslips in RPMI medium for 1 h, washed, and then incubated with S. flexneri as described above. After 40 min, coverslips were washed three times with PBS to remove extracellular bacteria and then fixed immediately with 3% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde for 10 min or cultured for 3 h prior to fixation. Cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and then incubated for 30 min with a rabbit anti-S. flexneri 5a lipopolysaccharide (LPS) polyclonal antibody (a gift from Armelle Phalipon, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) at a dilution of 1:1000 in 0.1% BSA in PBS. After three washes with 0.1% BSA in PBS, cells were incubated for 30 min with a Cy-3 coupled anti-rabbit antibody (1:1000) (Jackson Laboratories) and Phalloidin-FITC (1:200) (Sigma) for labeling of F-actin. Coverslips were then washed and mounted in 80% glycerol containing 10 mg of DABCO (Sigma)/ml and viewed by fluorescence microscopy.

Transmission electron microscopy (EM).

Monocytes were infected for 40 min with S. flexneri, and gentamicin was then added either with or without prior washing of cells to remove residual extracellular bacteria. Infected monocytes were either cultured for a further 8 h or processed immediately. Monocytes were fixed with freshly prepared 4% glutaraldehyde in cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) overnight and then scraped from the tissue culture plate to be washed three times in buffer. The postfixation step was performed using 1% osmium tetroxide followed by three further washes in buffer. Following dehydration and further processing, samples were embedded in Spur's resin. Sections 60- to 90-nm thick were cut using a diamond knife, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and viewed using a Zeiss EM 900 electron microscope.

Detection of TNF-α and IL-1β by ELISA.

Concentrations of IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in cell supernatants at various time points postinfection were determined by ELISA (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR.

RNA was extracted by direct lysis of the adherent cells with a solution containing guanidine isothiocyanate, followed by phenol-chloroform extractions. Reverse transcription (RT) was performed using Superscript II RT (Gibco BRL), and PCR was performed using Qiagen Master Mix with primers for TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, or β-actin (Interactiva, Ulm, Germany), as shown in Table 1. The primers recognized those sites which were separated by an intron in genomic DNA to ensure that recognition of the bands observed was due to the presence of reverse-transcribed mRNA only. The PCR products were run on an agarose gel containing ethidium bromide.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of primers used in this study and PCR product sizes

| Primer | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | PCR product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| TNF-α I | CGA ACC CCG AGT GAC AAG CC | 447 |

| TNF-α II | GAT CCC AAA GTA GAC CTG CC | |

| β-actin I | GTG GGG CGC CCC AGG CAC CA | 540 |

| β-actin II | CTC CTT AAT GTC ACG CAC GAT TTC | |

| IL-1β I | ATG GCA GAA GTA CCT AAG CTC GC | 776 |

| IL-1β II | ACA CAA ATT GCA TGG TGA AGT CAG TT | |

| IL-6 I | ATG AAC TCC TTC TCC ACA AGC GC | 627 |

| IL-6 II | GAA GAG CCC TCA GGC TGG ACT G |

DNA isolation and electrophoresis.

Monocytes (5 × 106) were infected with either M90T or BS176 as described above. Extracellular bacteria were washed off, and cells were cultured for a further 5 h in the presence of gentamicin. In parallel, an equal number of monocytes was cultured with 10 μM gliotoxin (Sigma), a fungal metabolite known to cause apoptosis in phagocytic cells (43). Cells were lysed in 0.4% Triton X-100-2 mM EDTA-10 mM Tris (pH 7.5). Nuclei were removed by centrifugation at 500 × g for 10 min, and the supernatants were incubated overnight with 50 μg of proteinase K/ml at 50°C. Samples were extracted with an equal volume of phenol-chloroform, incubated with 20 μg RNase (Boehringer)/ml for 2 h at 37°C, and then extracted again with phenol-chloroform. DNA in the aqueous phase was precipitated overnight at −20°C with 50% isopropanol-0.5 M NaCl, washed in 70% ethanol, and then dissolved in 10 mM Tris [pH 8.0]-0.5 M EDTA. Samples were electrophoresed for 60 min at 80 V through a 1% agarose gel containing 1 μg of ethidium bromide/ml in a Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0). DNA was visualized by UV light for photography.

Statistical methods.

All results are expressed as means ± standard deviations unless otherwise indicated. Statistical significance was assessed using the Student t test.

RESULTS

Inefficient S. flexneri infection of monocytes in the absence of opsonization.

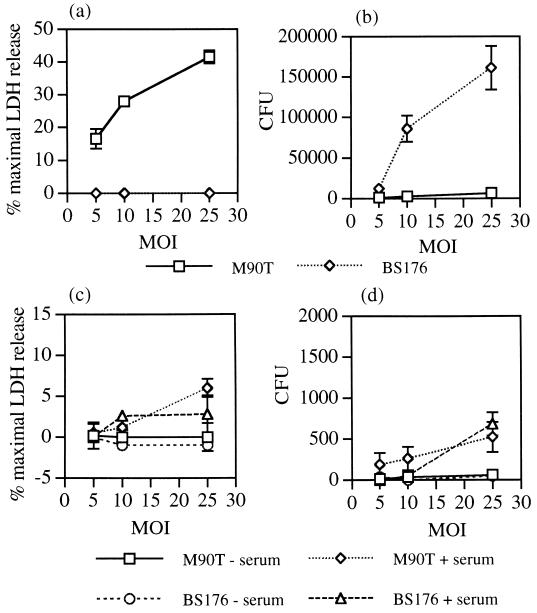

We initially compared the ability of S. flexneri to infect and kill freshly isolated monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages. Centrifugation of virulent (M90T), but not avirulent (BS176), S. flexneri onto macrophage monolayers resulted in cell death within 2 h, as detected by release of the cytosolic enzyme LDH into the supernatant (Fig. 1a). The number of live intracellular bacteria was measured using a gentamicin protection assay. Gentamicin was added after 40 min to kill extracellular bacteria, cells were lysed at 2 h, and the numbers of live intracellular bacteria were enumerated by plating on agar. Large numbers of BS176 were recovered (approximately 2% of inoculum at an MOI of 25:1), but very few M90T were recovered (<0.01% of inoculum at all MOIs), presumably due to entry of gentamicin into the dying cell (Fig. 1b). These results are in agreement with those of previous studies investigating the phagocytosis of S. flexneri by human monocyte-derived macrophages (13). In addition to demonstrating that wild-type S. flexneri can kill human macrophages, these results also indicate that macrophages do not kill all the phagocytosed avirulent S. flexneri within the first 2 h.

FIG. 1.

Cytotoxicity and intracellular survival of virulent (M90T) and avirulent (BS176) S. flexneri within macrophages and monocytes. Macrophage (a) and monocyte (c) cytotoxicity was assessed by release of LDH into the culture medium after 2 h of infection over a range of MOIs. Gentamicin was added after 40 min to halt infection and kill extracellular bacteria. Intracellular survival of S. flexneri within macrophages (b) and monocytes (d) was assessed in parallel at 2 h by lysing cells and counting the number of viable intracellular bacteria following culture of lysates on TSB plates. CFU values are the mean total numbers of bacteria isolated from each well ± standard deviations of triplicate cultures and are representative of three independent experiments. The results depicted in panels a and b are for bacteria that were unopsonized. The results depicted in panels c and d are for bacteria that were either unopsonized or opsonized for 30 min in 6% human serum prior to infection.

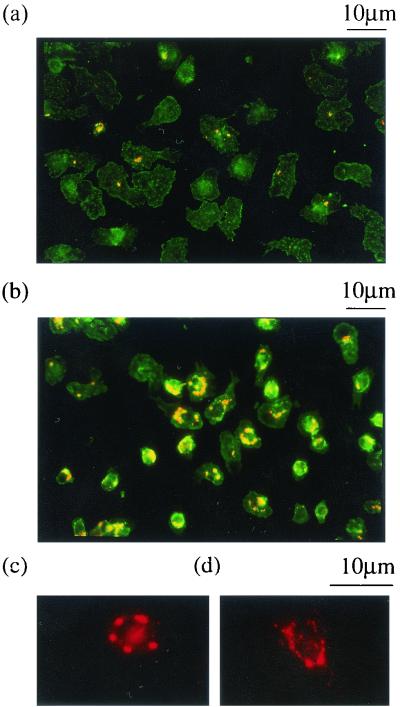

In contrast to results obtained with macrophages, centrifugation of virulent or avirulent S. flexneri onto monocytes did not result in cytotoxicity over the first 2 h (Fig. 1c), and moreover, very few (<100/well) intracellular bacteria were detected in the gentamicin protection assay (Fig. 1d). To determine whether S. flexneri infection of monocytes took place under these conditions, intracellular bacteria were detected using an anti-LPS antibody and observed by fluorescence microscopy. After 45 min of infection at an MOI of 25:1, less than half of the monocytes had taken up virulent S. flexneri, and the majority of infected cells contained only one intracellular bacterium (Fig. 2a). Similar results were obtained with BS176. Thus, both monocyte phagocytosis and, moreover, S. flexneri invasion of monocytes are inefficient in the absence of opsonization.

FIG. 2.

Immunofluorescence microscopy of S. flexneri-infected monocytes. The results depicted in panel a are for monocytes that were incubated with unopsonized S. flexneri (M90T) for 40 min at an MOI of 25:1, and those for panel b are for monocytes that were incubated with serum-opsonized S. flexneri (M90T) for 40 min at an MOI of 5:1. Bacteria that were labeled with a polyclonal anti-S. flexneri LPS antibody and a Cy3-coupled anti-rabbit Ig antibody appear as orange-yellow in the panel. The cell morphology is demonstrated using fluorescein isothiocyanate-coupled phalloidin, which binds F-actin (green). (c and d) Higher-magnification views of M90T-infected monocytes 1 (c) and 3 (d) h after infection, labeled with a polyclonal anti-S. flexneri LPS antibody and a Cy3 coupled anti-rabbit Ig antibody (red). Intact intracellular bacteria were seen at 1 h, but at 3 h they were much less distinct and punctate LPS staining was seen throughout the cell.

Monocytes kill S. flexneri after complement-dependent phagocytosis.

Monocyte phagocytosis of S. flexneri was assessed following bacterial opsonization. Incubation of 6% serum-opsonized S. flexneri with monocytes at an MOI of 5:1 for 40 min resulted in infection of >80% of monocytes with 2.4 ± 1.4 of M90T bacteria and 2.7 ± 1.8 of BS176 bacteria per cell (means ± standard errors of the means of three experiments, with >100 cells counted in each experiment) (Fig. 2b). This demonstrated equal uptake of the virulent and avirulent strains by monocytes, implying no role for the Shigella Ipa proteins in monocyte infection following opsonization of bacteria. Serum samples that had been heated at 56°C for 30 min prior to opsonization did not support phagocytosis, indicating that opsonization was complement dependent (data not shown). The ability of S. flexneri to cause monocyte cytotoxicity was therefore assessed following complement-dependent uptake. At an MOI of 5 to 10:1, there was no monocyte cytotoxicity at 2 h postinfection with either virulent or avirulent S. flexneri, and at an MOI of 25:1, which resulted in the uptake of large numbers of bacteria detected by immunofluorescence, cytotoxicity levels were consistently low (<10%) with both strains (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, there were very few live intracellular bacteria detected with the gentamicin protection assay at all MOIs (<1,000/well) (Fig. 1d). The effect of S. flexneri opsonization on macrophage cytotoxicity was also assessed. Bacterial opsonization increased macrophage cytotoxicity by up to twofold, indicating that S. flexneri-mediated cytotoxicity was still active in the presence of complement (data not shown). Taken together, these results demonstrate complement-dependent uptake and killing of both virulent and avirulent S. flexneri by monocytes in the absence of early monocyte cell death.

S. flexneri cannot escape from the monocyte phagocytic vacuole.

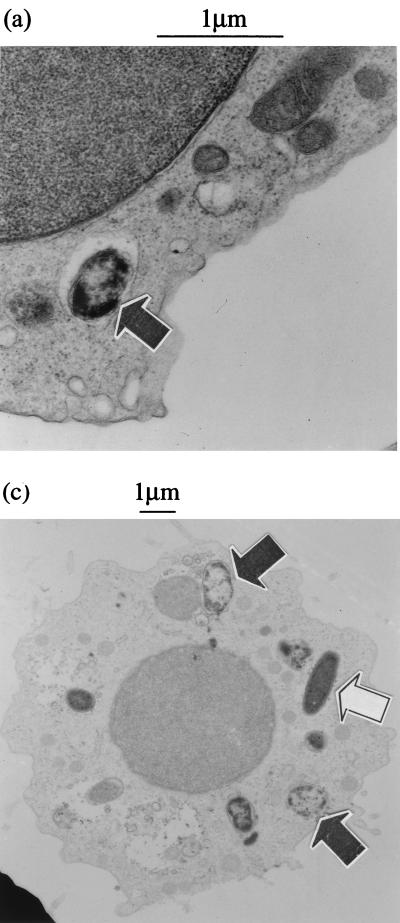

S. flexneri has to escape from the phagosome to cause macrophage cell death, and this has been shown to occur within 30 min of infection (7, 45). Immunofluorescence microscopy of S. flexneri-infected monocytes after 40 min of infection generally showed an identifiable outline of intracellular bacteria, with occasional adjacent punctate LPS staining (Fig. 2c). After 3 h of culture, the bacterial outline was indistinct and there were large amounts of punctate LPS staining throughout the cell (Fig. 2d), suggesting bacterial containment within the endosomal compartment and contact with lysosomal enzymes. To confirm this possibility and to ensure that the stained bacteria were truly intracellular, infected monocytes were analyzed by EM. Infected cells were processed between 30 and 60 min after phagocytosis of both virulent and avirulent S. flexneri. The EM pictures obtained were similar for both strains. The majority of virulent and avirulent bacteria could be unambiguously assigned to a phagosome, due to the presence of an intact vacuolar membrane around the bacteria (M90T and BS176; Fig. 3). In many cases, both M90T and BS176 were in the process of disruption, seen best at higher magnification in Fig. 3b. For some bacteria, the surrounding vacuolar membrane was not visible around the whole bacterium, but such images were seen in equal numbers with BS176 and M90T, implying that this was likely related to the cell preparation procedure and not a phenomenon related to expression of the virulence plasmid.

FIG. 3.

Transmission EM of monocytes infected with serum-opsonized virulent (M90T) (a and b) and avirulent (BS176) (c) S. flexneri. Cells were incubated with S. flexneri for 60 min prior to processing. Both M90T and BS176 can be seen within vacuoles with clearly defined vacuolar membranes and show signs of degeneration (closed arrowheads). The open arrowhead indicates a single undegraded intracellular BS176 bacterium.

IpaB-dependent suppression of IL-1β and TNF-α release from infected monocytes.

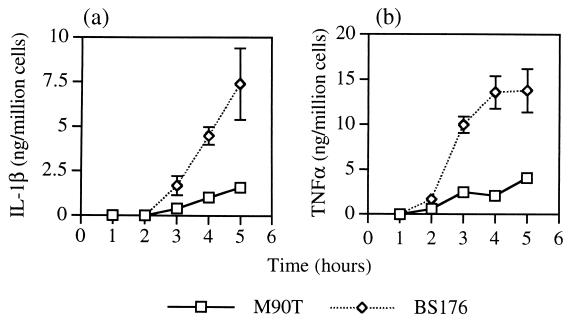

S. flexneri infection of macrophages is known to regulate production of mature IL-1β by IpaB-dependent activation of caspase-1 (16). We therefore measured the release of IL-1β and TNF-α during the first few hours following monocyte infection with opsonized S. flexneri. Surprisingly, there was much reduced release of both cytokines from monocytes infected with wild-type S. flexneri (M90T) compared with the avirulent strain (BS176). (Fig. 4a and b). Monocytes were also infected with an opsonized S. flexneri IpaB mutant to determine whether IpaB was required for the suppression of cytokine release. The amounts of IL-1β and TNF-α released were identical for BS176- and IpaB mutant-infected monocytes, indicating that cytokine suppression was dependent on the presence of IpaB (Table 2).

FIG. 4.

IL-1β and TNF-α release from monocytes infected with serum-opsonized S. flexneri. Monocytes were infected with virulent (M90T) and avirulent (BS176) S. flexneri for 40 min prior to the addition of gentamicin. Supernatants were taken at the indicated times for ELISA measurement of IL-1β (a) and TNF-α (b). Each point represents the mean ± standard deviation of triplicate wells. Uninfected monocytes released less than 250 pg of cytokine/million cells within 5 h of culture. An identical experiment was repeated once with similar results.

TABLE 2.

IL-1β and TNF-α release from monocytes infected for 5 h with M90T, BS176, and an S. flexneri IpaB mutanta

| Infecting strain | TNF-α (ng/ml) | IL-1β (ng/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| M90T | 9.21 ± 1.81b | 3.85 ± 0.57b |

| BS176 | 17.68 ± 1.22 | 14.05 ± 2.36 |

| IpaB | 18.52 ± 1.39 | 13.63 ± 0.97 |

| Uninfected | <0.5 | <0.5 |

Mean values ± standard deviation of six replicates.

There was significantly less TNFα and IL-1β from M90T-infected monocytes than from BS176- or IpaB mutant-infected monocytes (P < 0.001).

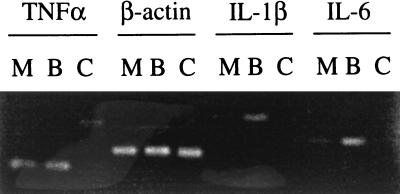

To determine whether S. flexneri-mediated cytokine inhibition occurred transcriptionally or posttranscriptionally, RT-PCR was performed on RNA from M90T- and BS176-infected monocytes by using primers specific for TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and β-actin as controls (Fig. 5). Very little mRNA for each cytokine was found in uninfected monocytes. There was an approximately threefold increase in synthesis of IL-1β and IL-6 mRNA in monocytes infected with BS176 compared with that with M90T. In contrast, there were equivalent increases in levels of TNF-α mRNA in both M90T- and BS176-infected cells. This difference in the effect of wild-type S. flexneri on regulation of TNF-α mRNA synthesis compared with that of IL-1β and IL-6 mRNA synthesis in infected cells may relate to the fact that TNF-α mRNA appears very early on after cell stimulation, possibly prior to IpaB-dependent suppression. M90T-induced suppression of IL-1β and IL-6 mRNA production was also seen after 5 h of infection (data not shown). Overall, these experiments demonstrate an inhibition of cytokine synthesis in virulent S. flexneri-infected monocytes acting both transcriptionally and posttranscriptionally.

FIG. 5.

Agarose gel showing RT-PCR products of RNA extracted from monocytes 2 h after infection with serum-opsonized M90T (M) and BS176 (B) S. flexneri by using primers specific for TNF-α, β-actin, IL-1β, or IL-6. C, uninfected control monocytes. Similar results were obtained in two further identical experiments.

Virulent S. flexneri induces monocyte apoptosis after death of the bacteria.

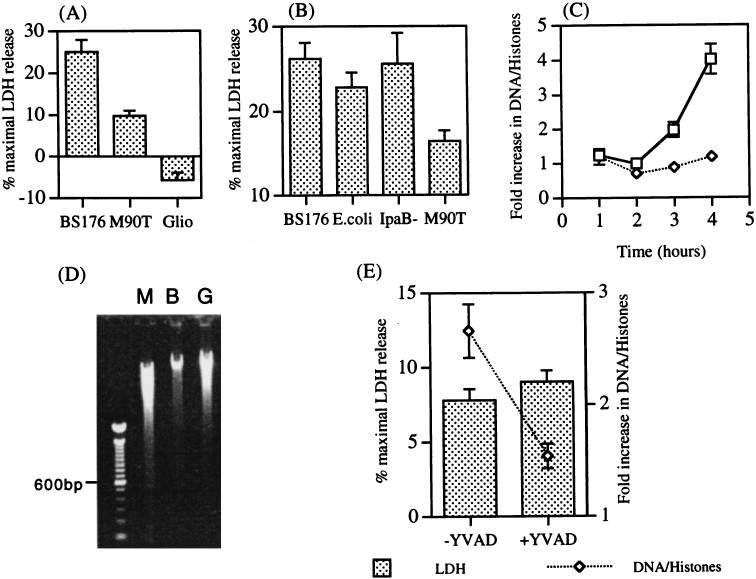

The observation that monocyte cytokine suppression was dependent on the presence of IpaB raised the possibility that it was secondary to induction of monocyte apoptosis (45). Infected monocytes were observed by light microscopy at over 6 to 8 h following infection. The most striking observation was that of a greater number of round, amorphous nonadherent dead cells in wells infected with BS176 compared with those infected with M90T (data not shown). Cytotoxicity of S. flexneri-infected monocytes was therefore investigated initially by measuring release of LDH into the supernatant. There was consistently a greater release of LDH from BS176-infected monocytes than from M90T-infected cells over the first 6 to 8 h of culture, a finding in support of the light microscopy observations (P < 0.005) (Fig. 6A). Greater LDH release was also seen following monocyte infection with the IpaB mutant and E. coli K12, implying that monocyte cytotoxicity associated with membrane damage is a general phenomenon following phagocytosis of gram-negative bacteria and that this cytotoxic mechanism can be inhibited by IpaB (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Detection of apoptosis and necrosis in monocytes infected with S. flexneri following death of the bacteria. (A) Supernatants were collected for measurement of LDH activity either 6 to 8 h after infection of monocytes with serum-opsonized virulent (M90T) and avirulent (BS176) S. flexneri or after 6 h of incubation with 10 μM gliotoxin (Glio). Values represent the mean percentages of maximal LDH release ± standard errors of the means of five (M90T and BS176) or three (gliotoxin) separate experiments performed in triplicate. (B) Monocytes were infected with serum-opsonized BS176, M90T, S. flexneri IpaB mutants, and E. coli K12. Supernatants were collected at 6 h for LDH measurement. Values represent the means ± standard deviations of triplicate cultures. The experiment was repeated once with similar results. (C) Cytoplasmic extracts were collected from monocytes infected with serum-opsonized M90T and BS176 at the indicated times. Results represent the severalfold increases in oligonucleosomal DNA fragments in cell extracts and are expressed as the means ± standard deviations of triplicate wells. (D) Electrophoresis of monocyte cytoplasmic DNA 6 h after infection with M90T (lane M) or BS176 (lane B) or following incubation with 10 μM gliotoxin (lane G). (E) Effect of YVAD on LDH release and DNA-histone complex production in M90T-infected monocytes. Monocytes were incubated with and without 100 μM YVAD for 1 h prior to infection with S. flexneri. Supernatants were taken 6 h after infection for LDH measurement, and cells were lysed for detection of DNA-histone complexes by ELISA.

The release of LDH is a nonspecific measure of cell death occurring during cell necrosis and the later stages of apoptosis (25). To determine more specifically whether infected monocytes were dying by apoptosis, the production of DNA-histone complexes was assessed in infected cells. There was a significant production of DNA-histone complexes from M90T-infected monocytes but not from BS176-infected cells beginning about 3 h postinfection, suggesting that M90T-infected monocytes were undergoing apoptosis (Fig. 6C). In three separate experiments, the mean severalfold increases (± standard errors of the means) in monocyte cytoplasmic DNA-histone complexes 4 h postinfection with M90T and BS176 were 4.4 ± 0.26 and 1.13 ± 0.2, respectively (P < 0.0006). To confirm that measurement of DNA-histone complexes reflected the characteristic internucleosomal DNA cleavage pattern associated with apoptosis, DNA was extracted and separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA from M90T-infected but not BS176-infected monocytes produced a 200-bp DNA ladder (Fig. 6D).

The LDH release and DNA-histone complex production from M90T-infected cells were compared with those from monocytes treated with gliotoxin, a known stimulator of apoptosis in mononuclear phagocytes (43). Gliotoxin treatment did not cause LDH release (Fig. 6A) but stimulated production of DNA-histone complexes (4.9 ± 1.2-fold increase in DNA-histone complexes at 4 h [n = 2]) and an early DNA ladder as assessed by gel electrophoresis at 6 h (Fig. 6D). Since gliotoxin-stimulated monocytes undergo apoptosis without LDH release, it was not clear whether the LDH release from M90T-infected monocytes was secondary to IpaB-dependent apoptosis or necrosis. We investigated these two possibilities by comparing the effect of the caspase-1 inhibitor YVAD on LDH release and DNA-histone complex production. YVAD had no effect on LDH release in both M90T-infected monocytes (Fig. 6E) and BS176-infected monocytes (data not shown). In contrast, YVAD partially blocked DNA-histone complex production in M90T-infected monocytes (Fig. 6E). Together, these results suggest that the low-level LDH release from M90T-infected monocytes is likely to be due to necrosis and is distinct from IpaB-activated, caspase-1-dependent apoptosis.

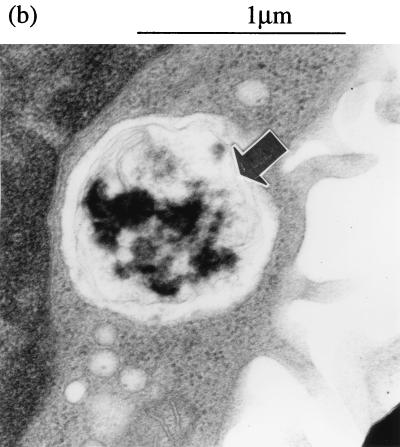

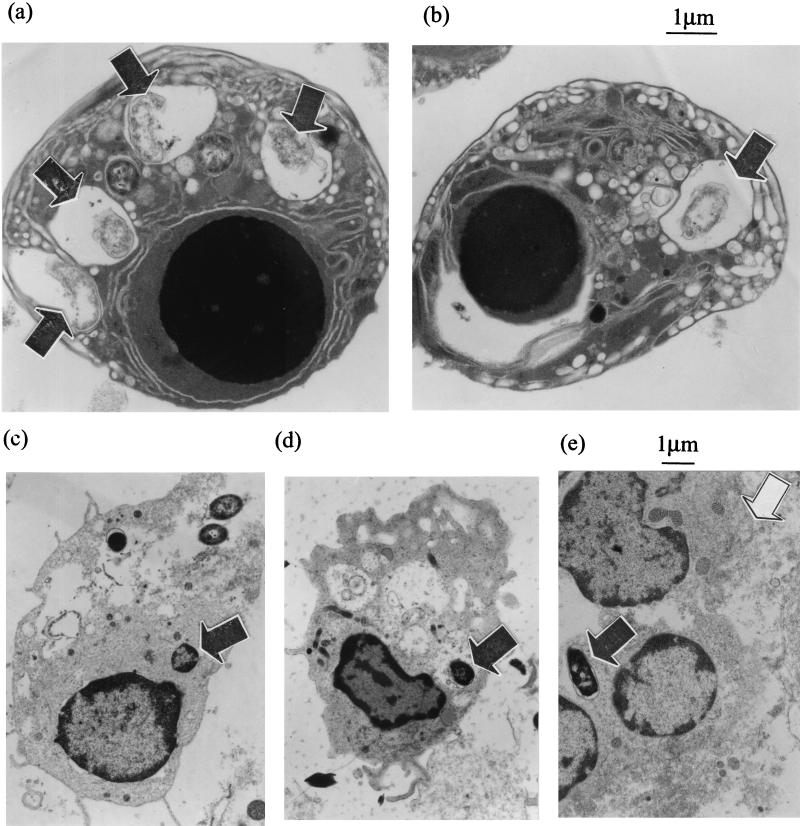

Apoptosis of M90T-infected monocytes was further demonstrated by EM of cells 8 h after phagocytosis. This revealed large numbers of apoptotic M90T-infected monocytes, identifiable by the presence of a shrunken condensed nucleus, with vacuolar degeneration of the cytoplasm and an intact outer cell membrane (Fig. 7a and b). Apoptotic cells contained degenerated bacteria within membrane-bound compartments, confirming that S. flexneri were killed within the phagosome and moreover implying that apoptosis in these cells can be induced without the need for bacterial escape into the cytoplasm. In contrast, cells with similar apoptotic morphology were not seen in sections of BS176-infected monocytes. Cells containing bacteria were present, but they were often partially disrupted (Fig. 7c to e), and there was a large amount of amorphous cellular material (Fig. 7d and e); together, these findings suggest that the cells were fragile and/or necrotic.

FIG. 7.

Transmission EM of monocytes infected with virulent (M90T) (a and b) and avirulent (BS176) (c to e) S. flexneri. Cells were processed 8 h after infection. Panels a and b show high-magnification views of apoptotic monocytes containing disrupted virulent S. flexneri within vacuoles (arrowheads). The monocytes contain one intracellular bacterium (b) and four intracellular bacteria (a), a finding which suggests the same apoptotic response and bacterial killing for different intensities of infection. Plates (c to e) show representative cells infected with avirulent S. flexneri. In panels c and d, the cells are intact but show some intracellular disruption, and in panel e, cellular material can be seen with no defined cell membrane, which is a result consistent with the cells undergoing necrosis.

DISCUSSION

There is good evidence that S. flexneri can kill murine J774 macrophages and human monocyte-derived macrophages in vitro (7, 13, 45). These macrophage populations are more representative of resident tissue macrophages, which are the first phagocytic cells to be infected by S. flexneri in vivo, rather than the activated inflammatory phagocytes which infiltrate the tissues in response to infection. It is known that unactivated resident tissue macrophages and monocyte-derived macrophages have poor microbicidal activity when tested in vitro (8, 9). They are highly active at phagocytosis, with multiple opsonin- and nonopsonin-dependent mechanisms of bacterial uptake (1, 31), but they are then relatively inefficient at rapidly killing the ingested bacteria, even those bacteria that are not known to have specific resistance mechanisms.

Within a few hours of Shigella infection, there is an influx of mononuclear phagocytes (monocytes) to the site of infection (3). These infiltrating monocytes are likely to rapidly outnumber resident macrophages and are known to have a much greater microbicidal capacity than resident macrophages, based on both in vitro (8, 9, 41) and in vivo observations (30). It is thus important to determine whether monocytes are better able to resist Shigella-mediated cytotoxicity and kill the bacteria.

The first important difference between S. flexneri infection of monocytes and macrophages is that monocytes take up bacteria inefficiently in the absence of opsonization. It is known that efficient bacterial phagocytosis by monocytes is opsonin dependent (41), but these results also show that S. flexneri cannot use the Ipa proteins to directly invade monocytes, in contrast to what has been recently described for macrophages (23). It has been reported that in the absence of specific opsonins, monocytes can use a CD14-dependent mechanism to phagocytose bacteria (14, 39), and this might account for the low-level uptake of both virulent and avirulent S. flexneri seen in our studies. Complement-dependent opsonization of S. flexneri with human serum resulted in efficient uptake, following which bacteria did not escape from the phagocytic vacuole and were rapidly killed. These results are in line with early work investigating the cell-mediated anti-Shigella activity of peripheral blood cells, including monocytes and neutrophils (24). Although optimal cytotoxicity was seen in the presence of immune serum, some monocyte bactericidal activity was also noted in the presence of complement alone. Complement-dependent uptake of Shigella by both monocytes and neutrophils is likely to be important during the early stages of infection, prior to the production of specific antibody.

Despite the killing of both virulent and avirulent S. flexneri during the first 2 h of infection, there were important differences in the response to infection in terms of cell fate and cytokine secretion. Monocytes infected with wild-type S. flexneri died by apoptosis based on EM morphology, DNA fragmentation that was inhibitable by YVAD, and low-level production of proinflammatory cytokines. Both apoptosis and cytokine suppression were not seen in monocytes infected with the IpaB mutant, suggesting an important role for IpaB. The precise mechanism of IpaB action and a more complete description of the apoptotic mechanism requires further study, especially in view of the pleiotropic effects of IpaB on cell invasion, phagosomal escape, and caspase-1 activation (15). These results are consistent with the findings of a recent study showing that S. flexneri infection of 24-h-in vitro-differentiated monocytes results in apoptosis (12), although in that study S. flexneri escaped the phagocytic vacuole, an event which may relate to a reduction in microbicidal capacity associated with the short-term culture. Monocytes infected with plasmid-cured S. flexneri and E. coli also died over 8 h postinfection, although the deaths occurred with features consistent with necrosis, namely pertinent light- and electron-microscopy-revealed morphologies, loss of membrane integrity without early DNA fragmentation, and high-level production of proinflammatory cytokines. The observation that BS176- and E. coli-infected monocytes develop an early loss of membrane integrity suggests that necrosis may be a general response to the phagocytosis of gram-negative bacteria. Such a conclusion requires further study, although it is relevant that IL-1β processing in monocytes is linked to necrotic cell death (18, 33), implying that cytotoxicity may be related to high-level cytokine processing rather than to bacterial phagocytosis per se. It is therefore of note that virulent S. flexneri appears to suppress the cytokine stimulation and anti-apoptotic signal delivered by LPS following bacterial phagocytosis (11, 28).

IpaB-dependent monocyte cell death showed important differences compared with macrophage cell death. Firstly, death of S. flexneri-infected macrophages is dependent upon bacterial survival and escape into the cytosol (7, 45), whereas monocyte death occurred following bacterial killing within the phagosome; secondly, macrophage death is characterized by a rapid loss of membrane integrity (13, 16), whereas monocyte membrane integrity was relatively conserved. Different mechanisms of S. flexneri-induced phagocytic cell death have previously been reported. Most notably, it has been shown that S. flexneri infection of gamma interferon-differentiated U937 cells results in apoptosis, whereas infection of retinoic acid-differentiated U937 cells results in cell death by oncosis (29). Oncosis is a recently described cell death mechanism defined by cell swelling and an early increase in membrane permeability in the absence of ordered DNA fragmentation (25). Furthermore, human monocyte-derived macrophages have been reported to die by either apoptosis (16) or oncosis (13). Taken together, these results suggest that phagocytic cells respond in different ways to IpaB-mediated cytotoxicity, and it will be important to assess whether this is relevant to disease pathogenesis.

Based on the observations made here, we propose that during the initial stages of shigellosis, S. flexneri infects resident tissue macrophages, leading to IL-1β release and rapid cell death characterized by an early increase in membrane permeability. This early membrane damage might facilitate bacterial escape from the dying cell, allowing Shigella to invade the surrounding epithelial cells. Subsequently, the phagocytosis of extracellular S. flexneri by infiltrating neutrophils and monocytes leads to bacterial killing, preventing further migration into the tissues and, in the case of monocytes, suppression of their proinflammatory cytokine response. Cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α are important for the early innate immune response in bacterial infection (4, 10), and moreover, TNF-α has been shown to kill S. flexneri-infected epithelial cells, suggesting that cytokine suppression might be important for early bacterial survival within epithelial cells (21). However, it is clear that high local intestinal levels of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, are present during established shigellosis (34, 35, 40). Perhaps a block in proinflammatory cytokine production at an early critical point in the disease process facilitates bacterial survival and proliferation, which then subsequently provokes the disordered inflammatory response that is characteristic of shigellosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ray Moss and Amanda Wilson for the electron microscopy.

This work was funded by The Wellcome Trust.

Editor: B. B. Finlay

REFERENCES

- 1.Aderem, A., and D. M. Underhill. 1999. Mechanisms of phagocytosis in macrophages. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17:593-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akita, K., T. Ohtsuki, Y. Nukada, T. Tanimoto, M. Namba, T. Okura, R. Takakura-Yamamato, K. Torigoe, Y. Gu, and S.-S. Su. 1997. Involvement of caspase-1 and caspase-3 in the production and processing of human interleukin-18 in monocytic THP-1 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 272:26595-26603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arondel, J., M. Singer, A. Matsukawa, A. Zychlinsky, and P. J. Sansonetti. 1999. Increased interleukin-1 (IL-1) and imbalance between IL-1 and IL-1 receptor antagonist during acute inflammation in experimental shigellosis. Infect. Immun. 67:6056-6066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bancroft, G. J., K. C. F. Sheehan, R. D. Schreiber, and E. R. Unanue. 1989. Tumor necrosis factor is involved in the T cell-independent pathway of macrophage activation in SCID mice. J. Immunol. 59:1709-1715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernadini, M. L., J. Mounier, H. d'Hauteville, M. Coquis-Rondon, and P. J. Sansonetti. 1989. Identification oficsA, a plasmid locus of Shigella flexneri which governs bacterial intra- and intercellular spread through interaction with F-actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:3867-3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgoyne, L. A., D. R. Hewish, and J. Mobbs. 1974. Mammalian chromatin substructure studies with the calcium-magnesium endonuclease and two-dimensional polyacrylamide-gel electrophoresis. Biochem. J. 143:67-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clerc, P. L., A. Ryter, J. Mounier, and P. J. Sansonetti. 1987. Plasmid-mediated early killing of eukaryotic cells by Shigella flexneri as studied by infection of J774 macrophages. Infect. Immun. 55:521-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czuprynski, C. J., P. A. Campbell, and P. M. Henson. 1983. Killing of Listeria monocytogenes by human neutrophils and monocytes, but not by monocyte-derived macrophages. J. Reticuloendothel. Soc. 34:29-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czuprynski, C. J., P. M. Henson, and P. A. Campbell. 1984. Killing of Listeria monocytogenes by inflammatory neutrophils and mononuclear phagocytes from immune and nonimmune mice. J. Leukoc. Biol. 35:193-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalrymple, S. A., L. A. Lucian, R. Slattery, T. McNeil, D. E. Aud, S. Fuchino, F. Lee, and R. Murray. 1995. Interleukin-6-deficient mice are highly susceptible to Listeria monocytogenes infection: correlation with inefficient neutrophilia. Infect. Immun. 63:2262-2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fahy, R. J., A. I. Doseff, and M. D. Wewers. 1999. Spontaneous human monocyte apoptosis utilizes a caspase-3-dependent pathway that is blocked by endotoxin and is independent of caspase-1. J. Immunol. 163:1755-1762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez-Prada, C. M., D. L. Hoover, B. D. Tall, A. B. Hartman, J. Kopelowitz, and M. M. Venkatesan. 2000. Shigella flexneri IpaH7.8 facilitates escape of virulent bacteria from the endocytic vacuole of mouse and human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 68:3608-3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez-Prada, C. M., D. L. Hoover, B. D. Tall, and M. M. Venkatesan. 1997. Human monocyte-derived macrophages infected with virulent Shigella flexneri in vitro undergo a rapid cytolytic event similar to oncosis but not apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 65:1486-1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grunwald, U., X. Fan, R. S. Jack, G. Workalemahu, A. Kallies, F. Stelter, and C. Schütt. 1996. Monocytes can phagocytose Gram-negative bacteria by a CD14-dependent mechanism. J. Immunol. 157:4119-4125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guichon, A., D. Hersh, M. R. Smith, and A. Zychlinsky. 2001. Structure-function analysis of the Shigella virulence factor IpaB. J. Bacteriol. 183:1269-1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hilbi, H., Y. Chen, K. Thirumalai, and A. Zychlinsky. 1997. The interleukin-1β-converting enzyme, caspase 1, is activated during Shigella flexneri-induced apoptosis in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Infect. Immun. 65:5165-5170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hilbi, H., J. E. Moss, D. Hersh, Y. Chen, J. Arondel, S. Banerjee, R. A. Flavell, J. Yuan, P. J. Sansonetti, and A. Zychlinsky. 1998. Shigella-induced apoptosis is dependent on caspase-1 which binds to IpaB. J. Biol. Chem. 273:32895-32900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hogquist, K. A., E. R. Unanue, and D. D. Chaplin. 1991. Release of IL-1 from mononuclear phagocytes. J. Immunol. 147:2181-2186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong, M., and S. M. Payne. 1997. Effect of mutations in Shigella flexneri chromosomal and plasmid-encoded lipopolysaccharide genes on invasion and serum resistance. Mol. Microbiol. 24:779-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Islam, D., B. Veress, P. K. Bardhan, A. A. Lindberg, and B. Christensson. 1997. In situ characterization of inflammatory responses in the rectal mucosae of patients with shigellosis. Infect. Immun. 65:739-749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klimpel, G. R., R. Shaban, and D. W. Niesel. 1990. Bacteria-infected fibroblasts have enhanced susceptibility to the cytotoxic action of tumor necrosis factor. J. Immunol. 145:711-717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotloff, K. L., J. P. Winickoff, B. Ivanoff, J. D. Clemens, D. L. Swerdlow, P. J. Sansonetti, G. K. Adak, and M. M. Levine. 1999. Global burden of Shigella infections: implications for vaccine development and implementation of control strategies. Bull. W. H. O. 77:651-666. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuwae, A., S. Yoshida, K. Tamano, H. Mimuro, T. Suzuki, and C. Sasakawa. 2001. Shigella invasion of macrophage requires the insertion of IpaC into the host plasma membrane: functional analysis of IpaC. J. Biol. Chem. 276:32230-32239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowell, G. H., R. P. MacDermott, P. L. Summers, A. A. Reeder, M. J. Bertovich, and S. B. Formall. 1980. Antibody-dependent cell-mediated antibacterial activity: K lymphocytes, monocytes, and granulocytes are effective against Shigella. J. Immunol. 125:2778-2784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Majno, G., and I. Joris. 1995. Apoptosis, oncosis, and necrosis. An overview of cell death. Am. J. Pathol. 146:3-15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandic-Muleg, I., J. Weiss, and A. Zychlinsky. 1997. Shigella flexneri is trapped in polymorphonuclear leukocyte vacuoles and efficiently killed. Infect. Immun. 65:110-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menard, R., P. J. Sansonetti, and C. Parsot. 1993. Nonpolar mutagenesis of the ipa genes defines IpaB, IpaC, and IpaD as effectors of Shigella flexneri entry into epithelial cells. J. Bacteriol. 175:5899-5906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newton, R. C. 1986. Human monocyte production of interleukin-1: parameters of the induction of interleukin-1 secretion by lipopolysaccharides. J. Leukoc. Biol. 39:299-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nonaka, T., A. Kuwae, C. Sasakawa, and S. Imajoh-Ohmi. 1999. Shigella flexneri YSH6000 induces two different types of cell death, apoptosis and oncosis, in the differentiated human monoblastic cell line U937. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 174:89-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.North, R. J. 1970. The relative importance of blood monocytes and fixed macrophages to the expression of cell-mediated immunity to infection. J. Exp. Med. 132:521-534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ofek, I., J. Goldhar, and Y. Keisari. 1995. Nonopsonic phagocytosis of microorganisms. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 49:239-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perdomo, J. J., M. Cavaillon, M. Huerre, H. Ohayon, P. Gounon, and P. J. Sansonetti. 1994. Acute inflammation causes epithelial invasion and mucosal destruction in experimental Shigellosis. J. Exp. Med. 180:1307-1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perregaux, D. G., R. E. Laliberte, and C. A. Gabel. 1996. Human monocyte interleukin-1β posttranslational processing. Evidence of a volume-regulated response. J. Biol. Chem. 271:29830-29838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raqib, R., A. A. Lindberg, B. Wretlind, P. K. Bardhan, U. Andersson, and J. Andersson. 1995. Persistence of local cytokine production in shigellosis in acute and convalescent stages. Infect. Immun. 63:289-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raqib, R., B. Wretlind, J. Andersson, and A. A. Lindberg. 1995. Cytokine secretion in acute shigellosis is correlated to disease activity and directed more to stool than to plasma. J. Infect. Dis. 171:376-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sansonetti, P. J., J. Arondel, J. M. Cavaillon, and M. Huerre. 1995. Role of IL-1 in the pathogenesis of experimental shigellosis. J. Clin. Investig. 96:884-892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sansonetti, P. J., J. Arondel, M. Huerre, A. Harada, and K. Matsushima. 1999. Interleukin-8 controls bacterial transepithelial translocation at the cost of epithelial destruction in experimental shigellosis. Infect. Immun. 67:1471-1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sansonetti, P. J., D. J. Kopeko, and S. B. Formal. 1982. Involvement of a plasmid in the invasive ability of Shigella flexneri. Infect. Immun. 35:852-860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schiff, D. E., L. Kline, K. Soldau, J. D. Lee, J. Pugin, P. S. Tobias, and R. J. Ulevitch. 1997. Phagocytosis of Gram-negative bacteria by a unique CD14-dependent mechanism. J. Leukoc. Biol. 62:786-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silva, D. G. H. D., L. N. Mendis, N. Sheron, G. J. M. Alexander, D. C. A. Candy, H. Chart, and B. Rowe. 1993. Concentrations of interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor in serum and stools of children with Shigella dysenteriae 1 infection. Gut 34:194-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steigbigel, R. T., L. H. Lambert, and J. S. Remington. 1974. Phagocytic and bactericidal properties of normal human monocytes. J. Clin. Investig. 53:131-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thornberry, N. A., H. G. Bull, J. R. Calaycay, K. T. Chapman, A. D. Howard, M. J. Kostura, D. K. Miller, S. M. Molineaux, J. R. Weidner, and J. Aunins. 1992. A novel heterodimeric cysteine protease is required for interleukin-1β processing in monocytes. Nature 356:768-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Waring, P., R. D. Eichner, A. Mullbacher, and A. Sjaarda. 1988. Gliotoxin induces apoptosis in macrophages unrelated to its antiphagocytic properties. J. Biol. Chem. 263:18493-18499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wassef, J. S., D. K. Keren, and J. M. Mailloux. 1989. Role of M cell in initial uptake and in ulcer formation in the rabbit intestinal loop model of shigellosis. Infect. Immun. 57:858-863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zychlinsky, A., B. Kenny, R. Ménard, M. C. Prévost, I. B. Holland, and P. J. Sansonetti. 1994. IpaB mediates macrophage apoptosis induced by Shigella flexneri. Mol. Microbiol. 11:619-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zychlinsky, A., M. C. Prevost, and P. J. Sansonetti. 1992. Shigella flexneri induces apoptosis in infected macrophages. Nature 358:167-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zychlinsky, A., K. Thirumalai, J. Arondel, J. R. Cantey, A. O. Aliprantis, and P. J. Sansonetti. 1996. In vivo apoptosis in Shigella flexneri infections. Infect. Immun. 64:5357-5365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]