Abstract

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a small bacterium without a cell wall that causes tracheobronchitis and atypical pneumonia in humans. It has also been associated with chronic conditions, such as arthritis, and extrapulmonary complications, such as encephalitis. Although the interaction of mycoplasmas with respiratory epithelial cells is a critical early phase of pathogenesis, little is known about the cascade of events initiated by infection of respiratory epithelial cells by mycoplasmas. Previous studies have shown that M. pneumoniae can induce proinflammatory cytokines in several different study systems including cultured murine and human monocytes. In this study, we demonstrate that M. pneumoniae infection also induces proinflammatory cytokine expression in A549 human lung carcinoma cells. Infection of A549 cells resulted in increased levels of interleukin-8 (IL-8) and tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA, and both proteins were secreted into culture medium. IL-1β mRNA also increased after infection and IL-1β protein was synthesized, but it remained intracellular. In contrast, levels of IL-6 and gamma interferon mRNA and protein remained unchanged or undetectable. Using protease digestion and antibody blocking methods, we found that M. pneumoniae cytadherence is important for the induction of cytokines. On the other hand, while M. pneumoniae protein synthesis and DNA synthesis do not appear to be prerequisites for the induction of cytokine gene expression, A549 cellular de novo protein synthesis is responsible for the increased cytokine protein levels. These results suggest a novel role for lung epithelial cells in the pathogenesis of M. pneumoniae infection and provide a better understanding of M. pneumoniae pathology at the cellular level.

Mycoplasmas are bacteria that lack cell walls and are the smallest and simplest free-living and self-replicating microorganisms. There are over 100 species of the genus Mycoplasma, and they vary widely in their pathogenicity and host ranges, infecting humans, animals, insects, and plants. Some species, such as Mycoplasma orale or Mycoplasma salivarium, belong to the normal flora of the human respiratory tract; however, other species are pathogens in humans. Mycoplasma pneumoniae is an agent of tracheobronchitis and primary atypical pneumonia, and Mycoplasma hominis is responsible for some episodes of pyelonephritis and/or salpingitis (3, 34). Mycoplasmas have been shown to affect the immune system using both in vitro and in vivo model systems. For example, they can activate macrophages, T cells, natural killer cells, and complement; stimulate the proliferation of B and T cells; and induce the expression of major histocompatibility complex class I and II molecules (4, 12, 18, 40, 41). It has also been shown that some mycoplasmas can induce the gene expression and production of cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, interferons (IFNs), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (14, 17, 35, 40, 44, 45, 53, 54).

Cytadherence of M. pneumoniae to the respiratory epithelium is regarded as an essential primary step in tissue colonization and subsequent disease pathogenesis (reviewed in reference 42 and references therein). The organism has developed a special organelle at the tip of the elongated flask-shaped cell that mediates attachment. Two surface proteins, the 170-kDa P1 and the 30-kDa P30 proteins, function as adhesins, while several other accessory proteins (HMW1, HMW2, and HMW3 and A, B, and C) collectively maintain the proper distribution and/or disposition of the adhesions in the mycoplasma membrane (3, 10, 27, 34). The effects of M. pneumoniae infection on the immune system also contribute to pathogenesis. High percentages of neutrophils and lymphocytes are present in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in patients with Mycoplasma pneumonia, and levels of IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, and IL-6 are elevated in both the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and serum of these patients (26, 30).

Cytokines are important mediators in both lung defense and inflammation (24). Chen et al. (7-9) have shown that IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α were induced in Pneumocystis carinii infection with a murine model, and these cytokines played important roles in host resistance to P. carinii by regulating the pulmonary inflammation responses, such as recruiting inflammatory cells into the lungs. On the other hand, Ulich et al. (48) reported that IL-6 and transforming growth factor β could down-regulate and curtail the exodus of neutrophils into local acute inflammatory sites, thus suggesting the presence of an endogenous negative feedback mechanism to inhibit endotoxin-initiated cytokine-mediated acute inflammation. In addition to the observation of elevated cytokine levels in Mycoplasma pneumonia patients, M. pneumoniae was also shown to induce proinflammatory cytokine gene expressions in mouse models, including expression of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, or IFN-γ (37, 38). M. pneumoniae also has similar effects on human peripheral blood mononuclear cells or Epstein-Barr virus-positive lymphoblastoid cell lines (25, 44). These data all point to the possible role of proinflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of M. pneumoniae. Although respiratory epithelial cells are the main targets of M. pneumoniae, there are no reports of their involvement in the cytokine response to infection with this respiratory pathogen. Because epithelial cells at mucosal surfaces have been shown to secrete chemoattractant and proinflammatory cytokines in response to bacterial infections (13), we decided to investigate the regulation and mechanisms of the cytokine response in respiratory epithelial cells during M. pneumoniae infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mycoplasma culture.

To prepare consistent M. pneumoniae stock for use in experiments, strain 15531 (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.) was grown in SP4 medium containing 18% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), and polymyxin (500 U/ml) at 37°C (2). M. pneumoniae cells in exponential growth phase were aliquoted and stored at −70°C. M. pneumoniae was quantified by measuring color change units or CFU (43).

Cell line and reagents.

A549 cells (human lung epithelial carcinoma cells; American Type Culture Collection) were grown in Earle's Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO, Grand Island, N.Y.). Cells were free of mycoplasmas as routinely determined by a Mycoplasma PCR Primer set (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). For M. pneumoniae treatment, 500 μl of M. pneumoniae from the same frozen stock was always added to 5 ml of cell culture medium (1:10, vol/vol; appropriately 5 × 107 CFU/106 cells) unless otherwise specified. Cycloheximide (CH), chloramphenicol (CP), and nalidixic acid (NA) were all purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). CH was prepared as a 1-mg/ml stock in EMEM and added to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. CP was dissolved in absolute ethanol as a 10-mg/ml stock and added to a final concentration of 20 μg/ml. NA was dissolved in EMEM as a 5-mg/ml stock and added to a final concentration of 40 μg/ml.

Cell viability assay.

The CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation assay (Promega, Madison, Wis.) is a colorimetric method for determining the number of viable cells in proliferation or cytotoxicity assays. It was performed as previously described (52). Briefly, 104 cells were seeded into a 96-well culture plate (Corning, Corning, N.Y.) and treated with M. pneumoniae for specified times. At the end of treatment, 20 μl of the CellTiter solution was added directly to each culture well and incubated at 37°C for 2 h, when the absorbance at 490 nm was determined with a Bio-Rad (Hercules, Calif.) microplate reader.

For cell counting, 105 cells were seeded into 12-well plates (Corning). After treatment, cells were harvested with 0.25% trypsin, and the number of trypan blue-excluding cells was determined with a hemacytometer.

Cytokine assays.

A total of 5 × 105 A549 cells were seeded into a six-well plate and treated with M. pneumoniae for up to 24 h. Cytokines secreted into the culture supernatant were detected using enzyme-linked immunosorbant assays (ELISAs). An OptEIA Human IL-1β set was used to detect IL-1β (15.6 to 1,000 pg/ml) (BD Biosciences, San Diego, Calif.), and the DuoSet ELISA Development systems were used to detect IL-6 (4.2 to 300pg/ml), IL-8 (31.25 to 2,000 pg/ml), IFN-γ (15.6 to 1,000 pg/ml), and TNF-α (15.6 to 1,000 pg/ml) (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.). All assays were conducted according to the manufacturers' instructions.

Immunofluorescent microscopy.

To detect intracellular IL-1β in A549 cells, an indirect immunofluorescent method was used. A total of 104 cells were seeded into a 96-well plate. At 24 h postinfection (PI), the culture medium was removed, and 200 μl of ice-cold methanol was added to each well to fix and permeate the cells for 5 min at room temperature. After the methanol was removed, 25 μl of mouse anti-human IL-1β antibody (dilution of 1:250; BD Biosciences) was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 30 min in the dark. The antibodies were removed, and wells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (0.01 M; pH 7.2). Twenty-five microliters of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled goat anti-mouse antibody (1:1,000; BD Biosciences) was then added to each well and incubated at 37°C for another 30 min in the dark. The secondary antibody was removed, the wells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and then mounting fluid (carbonate-buffered glycerol mounting fluid; pH 9.0) was added. The plate was evaluated with an Olympus IX70 fluorescent microscope. Images were captured and analyzed with the Optronics (Goleta, Calif.) program.

RNA preparation and quantification.

Total RNA was prepared from A549 cells with the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). Briefly, medium was completely removed from the culture flasks, and then 350 μl of RLT lysis buffer (Qiagen) was added into each 25-cm2 flask to lyse the cells. After the lysate was transferred to a 1.5-ml collection tube, 350 μl of 70% ethanol was added and mixed well by repeated pipetting. The mixture was again transferred to an RNeasy mini spin column and centrifuged for 15 s at 8,000 × g. The column was then washed with RW1 and RPE buffer (Qiagen), and finally the RNA was dissolved in 30 μl of DNase- and RNase-free water. The quantity and purity of the RNA samples were determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm and the 260 nm/280 nm absorbance ratio with a spectrometer.

RT-PCR.

Ready-To-Go RT-PCR beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Piscataway, NJ) were used for the reverse transcription (RT)-PCR assay. Total RNA (0.5 μg) was added to each reaction mixture. The primer sequences were as follows: IL-1β, 5′-AAA CAG ATG AAG TGC TCC TTC CAG G-3′ and 5′-TGG AGA ACA CCA CTT GTT GCT CCA-3′ (16); IL-6, 5′-GGC TGA AAA AGA TGG ATG CT-3′ and 5′-CCT GCT TCA CCA CCT TCT G-3′ (53); IL-8, 5′-AGA TAT TGC ACG GGA GAA-3′ and 5′-GAA ATA AAG GAG AAA CCA-3′; β-actin, 5′-CGG GAC CTG ACT GAC TAC-3′ and 5′-GAA GGA AGG CTG GAA GAG-3′ (31); IFN-γ, 5′-GAT GCT CTT CGA CCT TGA AAC AGC AT-3′ and 5′-ATG AAA TAT ACA AGT TAT ATC TTG GCT TTT-3′ (15); and TNF-α, 5′-GAG TGA CAA GCC TGT AGC CCA TGT TGT AGC A-3′ and 5′-GCA ATG ATC CCA AAG TAG ACC TGC CCA GAC T-3′ (49). The RT was carried out at 42°C for 30 min, and the amplifications were carried out for 32 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 60 s at 72°C. The products were run on a 2% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The gels were then scanned with a FluorImager SI (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.) and quantified using the ImageQuant program, version 4.2A (Molecular Dynamics), and the percentage of surface area under the peak of each band was normalized to that of the corresponding β-actin band.

Adherence blockage assay.

A mouse anti-M. pneumoniae monoclonal antibody (immunoglobulin G2a [IgG2a] isotype; Chemicon International, Inc., Temecula, Calif.) which targets the P1 adhesin protein was incubated with M. pneumoniae stock solution at a 1:10, 1:100, or 1:1,000 ratio for 2 h at room temperature. The cells were then inoculated with the mixture, and after 4 h the total RNA was extracted and assayed for IL-1β mRNA. A purified mouse IgG2a antibody with an unrelated epitope was used as an isotype control (Caltag).

Protease digestion treatment.

Protease digestion was conducted as described by Hu et al. (22) with some modifications. In some experiments, M. pneumoniae was pretreated with trypsin (GIBCO) for 20 min at 37°C at a final concentration of 100 μg/ml to remove surface adhesion proteins and was then used to infect A549 cells.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed with Student's t test. A probability level of P < 0.05 was considered significant. Data are presented as the mean ± the standard deviation.

RESULTS

M. pneumoniae infection induces proinflammatory cytokine gene expression in A549 cells.

Cultures of A549 cells were infected with M. pneumoniae (or sterile SP4 medium as a control) for up to 24 h. Neither M. pneumoniae nor SP4 medium affected cell viability by the CellTiter assay or cell proliferation by direct cell count during this 24-h period (from 1 ×105 to 5 × 107 CFU), although some cytotoxic effects (20 to 30% decrease in cell viability) could be detected with a much higher infection ratio and longer incubation times than were used in the experiments (>108 CFU and up to 3 days) (data not shown). Total RNA was prepared from infected A549 cells, A549 cells cultured with SP4 medium (as a medium control), and untreated A549 cells.

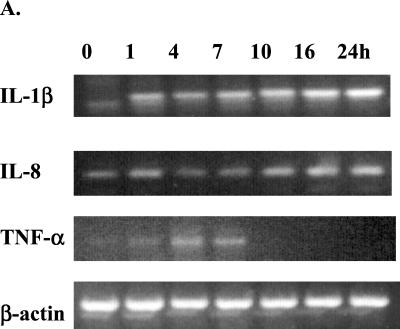

When tested by RT-PCR with β-actin as an internal control, it was found that mycoplasma infection of A549 cells resulted in elevation of IL-1β, IL-8, and TNF-α mRNA (Fig. 1), whereas IL-6 and IFN-γ mRNA levels remained the same or undetectable (data not shown). IL-1β mRNA was induced as soon as 1 h PI, with the signal becoming gradually stronger until 24 h PI. Occasionally, a faint nonspecific band below the IL-1β band could be seen in IL-1 β RT-PCR gels in the samples, but it did not interfere with the IL-1β band. IL-8 had a rather strong baseline mRNA expression compared to IL-1β, and the induction became obvious around 8 h PI. The induction of TNF-α was the most transient; its mRNA appeared around 1 h PI, peaked around 4 to 8 h, and then rapidly decreased. There was a baseline expression of IL-6 mRNA, but it remained unchanged during infection (data not shown). IFN-γ mRNA, however, was not detected in either the control or the infected cells. The A549 cells cultured with SP4 medium had the same mRNA levels as the control cells in all experiments (data not shown). The three groups (A549 infected, A549 SP4 medium control, and untreated A549 cells) had the same levels of β-actin mRNA expression during the 24-h period (Fig. 1 and data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Induction of proinflammatory cytokine mRNA expressions in A549 cells during M. pneumoniae infection. A549 cells were inoculated with M. pneumoniae for 1 to 24 h; total RNA was extracted; and cellular levels of IL-1β, IL-8, and TNF-α were measured by RT-PCR. β-Actin was used as an internal control. (A) Electrophoretogram of RT-PCR. The RT-PCR products were run on agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized with UV light. (B) Densitometric quantification of the electrophoretogram shown in panel A after normalization to β-actin. The densitometric values were analyzed by Student's t test. ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01.

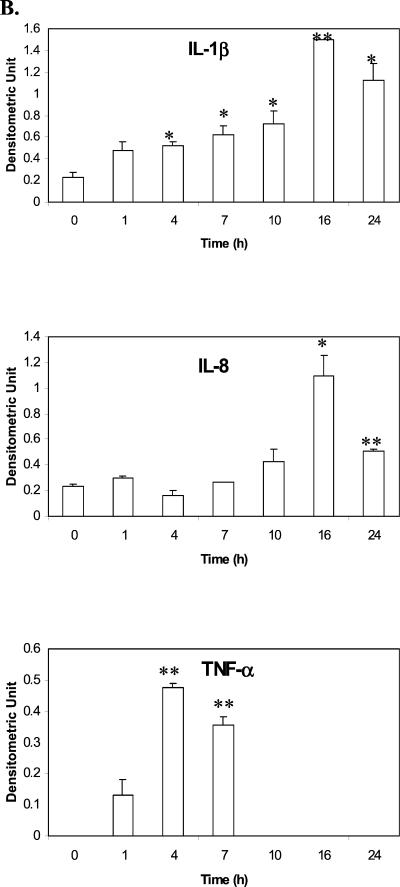

IL-1β, IL-8, and TNF-α have different protein expression patterns.

Because IL-1β, IL-8, and TNF-α mRNA levels were increased after M. pneumoniae infection, the levels of protein expression for these cytokines were investigated. Cell culture supernatants were collected at specific time points and analyzed for cytokine expression by ELISAs. As shown in Fig. 2A, it was found that IL-8 protein levels steadily increased during the 24-h infection period. TNF-α protein was also expressed, but unlike IL-8, expression reached its peak just hours after infection and then started decreasing around 12 h PI (Fig. 2B). ELISA detected no IL-6 expression, as expected (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Increased IL-8 and TNF-α secretion in A549 cells in response to M. pneumoniae infection. Each time point was measured in triplicate; error bars represent the standard deviation. A549 cells were either untreated controls (time zero) or inoculated with M. pneumoniae. At the time points specified, culture supernatants were collected, and secreted IL-8 was measured by ELISA. (B) Time course of TNF-α secretion. A549 cells were infected with M. pneumoniae, then culture supernatants were removed, and TNF-α levels were measured by ELISA at the times indicated. Each time point was compared to the value of time zero, and the data were analyzed by Student's t test. ∗, P < 0.01.

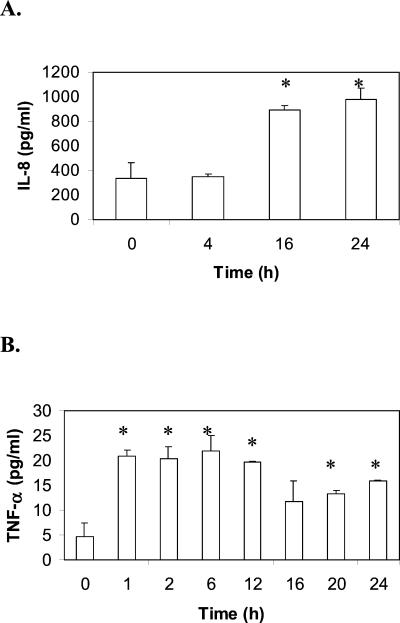

Despite detection of IL-1β mRNA in infected A549 cells, we did not detect any IL-1β protein in supernatants. An immunofluorescent microscopy technique was then used to determine if IL-1β protein expression was occurring in the absence of secretion into the supernatant. As shown in Fig. 3, by using a specific mouse anti-human IL-1β antibody with an FITC-conjugated secondary antibody, it was found that M. pneumoniae infected cells were stained, while the control cells were not. This indicated that the IL-1β protein was indeed synthesized after infection but was not secreted out of the cells.

FIG. 3.

Immunofluorescent detection of intracellular IL-1β. A549 cells were either untreated (Control) or inoculated with M. pneumoniae for 24 h. Cells were then stained with a specific mouse anti-human IL-1β antibody, followed by an FITC-labeled goat anti-mouse antibody. The images were then captured and analyzed. The presence of IL-1β antigen is demonstrated in the M. pneumoniae-infected cells but not in uninfected control cells.

M. pneumoniae cytadherence is important for cytokine induction.

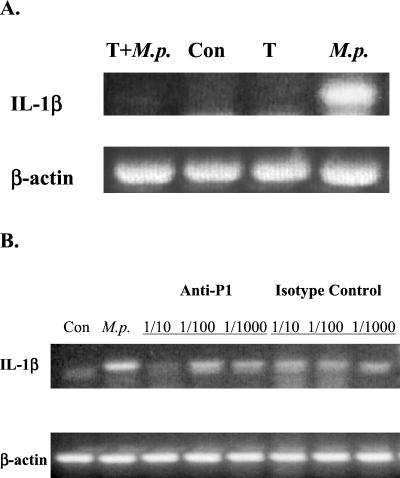

Because M. pneumoniae pathogenesis appears to begin when cell attachment occurs (42), we wanted to determine the role of cytadherence in the induction of cytokine gene expression. To do that, two approaches were employed. The first approach relied upon observations by Hu et al. (22) that protease treatment of M. pneumoniae degrades the P1 protein and prevents attachment of M. pneumoniae attachment to host cells without reducing the viability of M. pneumoniae. Accordingly, the mRNA levels of IL-1β from A549 cells infected with protease-treated and untreated M. pneumoniae were compared. As shown in Fig. 4A, protease treatment of M. pneumoniae strongly inhibited the induction of IL-1β mRNA.

FIG. 4.

Cytadherence is important for M. pneumoniae infection-induced proinflammatory cytokine gene expression. IL-1β was used as the indicator for gene expression, and β-actin was used as an internal control. (A) Protease digestion experiment. A549 cells were either untreated (Con), mock-treated with Trypsin (T), infected with M. pneumoniae (M.p.), or inoculated with trypsin-digested M. pneumoniae (T+M.p.) for 4 h. Total RNA was extracted, and IL-1β mRNA levels were measured by RT-PCR. (B) Antibody blockage experiment. M. pneumoniae was incubated with either a specific anti-P1 antibody or an isotype control antibody for 2 h at room temperature at different dilutions. A549 cells were then inoculated with these mixtures or M. pneumoniae only (M.p.) for 4 h. Total RNA was extracted, and IL-1β mRNA levels were measured by RT-PCR.

The second approach utilized an anti-P1 monoclonal antibody that can inhibit the attachment of M. pneumoniae to respiratory epithelium (28). As shown in Fig. 4B, when A549 cells were infected with M. pneumoniae preincubated with anti-P1 antibodies at a dilution of 1:10, IL-1β induction was also strongly inhibited. Higher dilutions did not have any effect on the induction of IL-1β, suggesting that at a 1:10 dilution the antibodies completely saturate the M. pneumoniae P1 binding sites, thus preventing attachment to A549 cells. The antibody alone did not have any effect on IL-1β message expression (data not shown). To exclude the possibility that this blockage was caused by nonspecific binding of antibody to M. pneumoniae, an unrelated mouse IgG2a isotype control was tested for its ability to inhibit cytokine induction. Our results clearly showed that this nonspecific antibody did not affect the induction of cytokines by M. pneumoniae infection (Fig. 4B). Therefore, we conclude that M. pneumoniae cytadherence is important in cytokine induction.

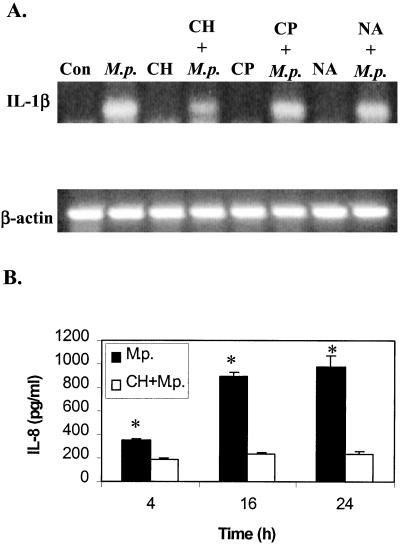

A549 cell protein synthesis is required for increased cytokine levels.

To examine whether the increase in cytokine levels was due to de novo protein synthesis, CH was added to the cell culture for 2 h before M. pneumoniae was added. At specific time points, culture medium was removed and IL-8 levels were measured. Although CH treatment did not affect the increased expression of cytokine genes (using IL-1β as an indicator) (Fig. 5A), it did inhibit the induction of IL-8 protein compared to that with M. pneumoniae infection alone (Fig. 5B). These data strongly suggested that de novo synthesis is required for the increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines.

FIG. 5.

Effects of antibiotics and CH on cytokine induction by M. pneumoniae infection. (A) A549 cells were either untreated (Con); infected with M. pneumoniae alone (M.p.); incubated with CH, CP, or NA alone; or preincubated with the chemicals for 2 h, followed by infection with M. pneumoniae (CH+M.p., CP+M.p., or NA+M.p.). After 4 h, total RNA was extracted, and IL-1β mRNA levels were measured by RT-PCR. β-Actin was used as an internal control. (B) A549 cells were either inoculated with M. pneumoniae (M.p.) alone or preincubated with CH for 2 h and then infected with M. pneumoniae (CH+M.p.). At the time points specified, culture supernatants were collected, and secreted IL-8 was measured by ELISA. The date were analyzed by Student's t test, ∗, P < 0.01.

M. pneumoniae protein synthesis and DNA synthesis are not required in the induction of cytokine gene expression in A549 cells.

As stated above, we have found that cytadherence is required for cytokine induction during M. pneumoniae infection, but we wished to find out if other factors were also involved, such as bacterial protein synthesis or DNA synthesis. CP inhibits bacterial protein synthesis by binding to the 50S subunit of the ribosome and inhibiting the peptidyltransferase step (32). NA antagonizes the A subunit of DNA gyrase and thus blocks bacterial DNA synthesis (51). These antibiotics were added to the cell culture medium and incubated for 2 h prior to the infection with M. pneumoniae. At the concentrations used (20 μg/ml for CP and 40 μg/ml for NA), M. pneumoniae growth was greatly inhibited as determined by the CFU counts (data not shown). Neither antibiotic alone induced IL-1β gene expression; however, we could detect induction of IL-1β mRNA by M. pneumoniae in the presence of either antibiotic (Fig. 5A). Therefore, neither bacterial protein synthesis nor DNA synthesis is required for cytokine induction during M. pneumoniae infection.

DISCUSSION

M. pneumoniae infections trigger an intense local inflammation that can be exacerbated upon reinfection, which eventually can lead to cell toxicity and tissue damage (34). Although the mechanisms remain elusive, it is thought that the inflammatory response at the site of the infection may be initiated by the release of soluble mediators that attract and activate other cells of myelomonocytic origin (37, 38). The findings we present here provide a strong support for this hypothesis. Furthermore, our data suggest a new role for lung epithelial cells in the cellular response to M. pneumoniae infection, namely, that the local inflammatory response can be initiated by the release of proinflammatory cytokines from these epithelial cells. M. pneumoniae can also induce cytokine production in human monocytes/lymphocytes, but it may occur later in the infection. Among the cytokines induced, IL-8 appears to play an important role, as it is a potent chemoattractant and activator of neutrophils, monocytes, and T lymphocytes and therefore is the major contributor for the neutrophil influx to the lung during bacterial infections (6, 29).

Although we detected the induction of IL-8 and TNF-α proteins in the cell culture medium by ELISA (Fig. 2), we did not detect the presence of any IL-1β protein in the culture medium. IL-1, unlike other cytokines, lacks the typical hydrophobic signal peptide (5, 23, 50). The mature form of IL-1β is a 17-kDa protein, which is processed from its 31-kDa (269-amino-acid) precursor (1). Intracellular IL-1β consists exclusively of the 31-kDa precursor form, while extracellular IL-1β consists of a mixture of both the unprocessed and mature forms of IL-1β (19). Further studies revealed that even though several cell types have the capacity to produce the IL-1β precursor, its release is predominantly limited to monocytes and macrophages (11). Therefore, by using an indirect immunofluorescent method, we did detect the presence of IL-1β protein in M. pneumoniae-infected cells but not in control or mock-treated cells (Fig. 3). This provided clear evidence that IL-1β protein was synthesized in human lung epithelial cells during the infection and that the protein remained intracellular instead of secreted. It is in consistent with a study conducted by Uchida et al.(47) in which it was shown that although IL-1β mRNA in human gingival epithelial cells was induced in response to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, secretion of IL-1β could not be detected. This is in direct contrast to some other reports that IL-1β is secreted during infection (25, 44). Therefore, the ability of epithelial cells to secret IL-1β protein may be very limited.

The mechanism for this limitation on the secretion may rely on the enzyme responsible for the processing of IL-1β. The IL-1β-converting enzyme (ICE; also called caspase 1) is able to process IL-1β and is also involved in apoptosis (33, 36, 46). Hogquist et al. (20, 21) had shown that IL-1β release is correlated with cell injury and that the processing of the precursor protein only occurs efficiently in cells that are undergoing apoptosis. However, we did not observe any significant cell damage in A549 cells during infection, and it is possible that the IL-1β-converting enzyme was not activated and, thus, that no mature IL-1β protein was secreted.

Several reports have demonstrated the induction of IL-6 in human lymphocytes, human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and/or mice during M. pneumoniae infection (25, 37, 44). However, we did not detect the induction of IL-6 in the A549 human epithelial cell line following M. pneumoniae infection at the level of sensitivity of our ELISA. On the other hand, we did detect the induction of IL-6 in TNF-α-treated A549 cells (data not shown). However, Uchida et al. (47) had reported that IL-6 was not induced in human gingival epithelial cells in response to A. actinomycetemcomitans, but human gingival fibroblasts responded to A. actinomycetemcomitans by increasing their IL-6 mRNA levels. Therefore, it appears that various cell types in different models respond to the same infectious agent with different cytokine induction profiles.

Even though cytadherence appears to be important for cytokine induction, some other mechanisms are most likely to be involved. For example, it has been reported that bacterial protein synthesis is required for the induction of IL-8 by epithelial cells following chlamydial infection (39). Therefore, the possible roles of M. pneumoniae protein synthesis and DNA synthesis in cytokine induction were also evaluated. Our results (Fig. 5A) showed that these two macromolecule syntheses do not appear to be prerequisites for M. pneumoniae-induced cytokine gene expressions. However, A549 cellular protein synthesis is responsible for increased cytokine protein levels, as CH, an inhibitor of eukaryotic protein synthesis, can abolish the increase of IL-8 levels during M. pneumoniae infection (Fig. 5B).

This study presents a new perspective in M. pneumoniae pathogenesis, as it sheds light on the mechanisms of acute inflammation during infection. The association of this bacterium with chronic diseases, such as asthma and arthritis, and the mechanisms for host cell damage can be partly attributed to the induction of these proinflammatory cytokines during infection. It should be kept in mind that results from in vitro studies do not always mimic in vivo responses in the host. The serum in the cell culture medium may also influence the cytokine response to M. pneumoniae infection. The A549 cells we used are derived from a human lung epithelial carcinoma, and a cell line not associated with disease, such as primary lung epithelial cells, will be useful in future studies.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank the colleagues of the Respiratory Diseases Laboratory Section at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for their help and advice during the preparation of the manuscript, especially S. Schwartz, L. Thacker, and R. Benson for their technical assistance and valuable suggestions.

J. Yang is an American Society for Microbiology/National Center for Infectious Diseases Postdoctoral Research Associate.

Editor: J. D. Clements

REFERENCES

- 1.Auron, P. E., S. J. Warner, A. C. Webb, J. G. Cannon, H. A. Bernheim, K. J. McAdam, L. J. Rosenwasser, G. LoPreste, S. F. Mucci, and C. A. Dinarello. 1987. Studies on the molecular nature of human interleukin 1. J. Immunol. 138:1447-1456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baseman, J. B., M. Lange, N. L. Criscimagna, J. A. Giron, and C. A. Thomas. 1995. Interplay between mycoplasma and host target cells. Microb. Pathog. 19:105-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baseman, J. B., and J. G. Tully. 1997. Mycoplasmas: sophisticated, reemerging, and burdened by their notoriety. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3:21-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernatchez, C., R. Al-Daccak, P. E. Mayer, K. Mehindate, L. Rink, S. Mecheri, and W. Mourad. 1997. Functional analysis of Mycoplasma arthritidis-derived mitogen interactions with class II molecules. Infect. Immun. 65:2000-2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjorkdahl, O., A. G. Wingren, G. Hedhund, L. Ohlsson, and M. Dohlsten. 1997. Gene transfer of a hybrid interleukin-1 beta gene to B16 mouse melanoma recruits leukocyte subsets and reduces tumour growth in vivo. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 44:273-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohnet, S., U. Kotschau, J. Braun, and K. Dalhoff. 1997. Role of interleukin-8 in community-acquired pneumonia: relation to microbial load and pulmonary function. Infection 25:95-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, W., E. A. Havell, F. Gigliotti, and A. G. Harmsen. 1993. Interleukin-6 production in a murine model of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia: relation to resistance and inflammatory response. Infect. Immun. 61:97-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, W., E. A. Havell, and A. G. Harmsen. 1992. Importance of endogenous tumor necrosis factor alpha and gamma interferon in host resistance against Pneumocystis carinii infection. Infect. Immun. 60:1279-1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, W., E. A. Havell, L. L. Moldawer, K. E. McIntyre, R. A. Chizzonite, and A. G. Harmsen. 1992. Interleukin-1: an important mediator of host resistance against Pneumocystis carinii. J. Exp. Med. 176:713-718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dallo, S. F., A. L. Lazzell, A. Chavoya, S. P. Reddy, and J. B. Baseman. 1996. Bifunctional domains of the Mycoplasma pneumoniae P30 adhesin. Infect. Immun. 64:2595-2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dinarello, C. A. 1991. Interleukin-1 and interkeukin-1 antagonism. Blood 77:1627-1652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Orazio, J. A., B. C. Cole, and J. Stein-Streilein. 1996. Mycoplasma arthritidis mitogen up-regulates human NK cell activity. Infect. Immun. 64:441-447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eckman, L., M. F. Kagnoff, and J. Fierer. 1995. Intestinal epithelial cells as watchdogs for the natural immune system. Trends Microbiol. 3:118-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faulkner, C. B., J. W. Simecka, M. K. Davidson, J. K. Davis, T. R. Schoeb, J. R. Lindsey, and M. P. Everson. 1995. Gene expression and production of tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 1, interleukin 6, and gamma interferon in C3H/HeN and C57BL/6N mice in acute Mycoplasma pulmonis disease. Infect. Immun. 63:4084-4090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenton, M. J., M. W. Vermeulen, S. Kim, M. Burdick, R. M. Strieter, and H. Kornfeld. 1997. Induction of gamma interferon production in human alveolar macrophages by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 65:5149-5156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gan, X., and B. Bonavida. 1999. Preferential induction of TNF-α and IL-1β and inhibition of IL-10 secretion by human peripheral blood monocytes by synthetic aza-alkyl lysophopholipids. Cell. Immunol. 193:125-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia, J., B. Lemercier, S. Roman-Roman, and G. Rawadi. 1998. A Mycoplasma fermentans-derived synthetic lipopeptide induces AP-1 and NF-κB activity and cytokine secretion in macrophages via the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 273:34391-34398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall, R. E., S. Agarwal, and D. P. Kestler. 2000. Induction of leukemia cell differentiation and apoptosis by recombinant P48, a modulin derived from Mycoplasma fermentans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 269:284-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hazuda, D. J., J. C. Lee, and P. R. Young. 1988. The kinetics of interleukin 1 secretion from activated monocytes. Differences between interleukin 1 alpha and interleukin 1 beta. J. Biol. Chem. 263:8473-8479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogquist, K. A., M. A. Nett, E. R. Unanue, and D. D. Chaplin. 1991. Interleukin 1 is processed and released during apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:8485-8489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hogquist, K. A., E. R. Unanue, and D. D. Chaplin. 1991. Release of IL-1 from mononuclear phagocytes. J. Immunol. 147:2181-2186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu, P. C., A. M. Collier, and J. B. Baseman. 1977. Surface parasitism by Mycoplasma pneumoniae of respiratory epithelium. J. Exp. Med. 145:1328-1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jarry, A., G. Vallette, E. Cassagnau, A. Moreau, C. Bou-Hanna, P. Lemarre, E. Letessier, J.-C. Le Neel, J.-P. Galmiche, and C. L. Laboisse. 1999. Interleukin1 and interleukin 1beta converting enzyme (caspase 1) expression in the human colonic epithelial barrier. Caspase 1 downregulation in colon cancer. Gut 45:246-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly, J. 1990. Cytokines of the lung. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 141:765-788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kita, M., Y. Ohmoto, Y. Hirai, N. Yamaguchi, and J. Imanishi. 1992. Induction of cytokines in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by mycoplasmas. Microbiol. Immunol. 36:507-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koh, Y. Y., Y. Park, H. J. Lee, and C. K. Kim. 2001. Levels of interleukin-2, interferon-γ, and interleukin-4 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with Mycoplasma pneumonia: implication of tendency toward increased immunoglobulin E production. Pediatrics 107:e39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krause, D. C. 1998. Mycoplasma pneumoniae cytadherence: organization and assembly of the attachment organelle. Trends Microbiol. 6:15-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krause, D. C., and J. B. Baseman. 1983. Inhibition of Mycoplasma pneumoniae hemadsorption and adherence to respiratory epithelium by antibodies to a membrane protein. Infect. Immun. 39:1180-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kunkel, S. L., T. J. Standiford, K. Kasahara, and R. M. Strieter. 1991. Interleukin-8 (IL-8): the major neutrophil chemotactic factor in the lung. Exp. Lung Res. 17:17-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lieberman, D., S. Livnat, F. Schlaeffer, A. Porath, S. Horowitz, and R. Levy. 1997. IL-1β and IL-6 in community-acquired pneumonia: bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia versus Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. Infection 25:90-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liechty, K. W., T. M. Crombleholme, D. L. Cass, B. Martin, and N. S. Adzick. 1998. Diminished interleukin-8 (IL-8) production in the fetal wound healing response. J. Surg. Res. 77:80-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lorian, V. 1986. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, Md.

- 33.Maeyama, T., K. Kuwano, M. Kawasaki, R. Kunitake, N. Hagimoto, T. Matsuba, M. Yoshimi, I. Inoshima, K. Yoshida, and N. Hara. 2001. Upregulation of Fas-signalling molecules in lung epithelial cells from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 17:180-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maniloff, J., R. N. McElhaney, L. R. Finch, and J. B. Baseman (ed.). 1992. Mycoplasmas: molecular biology and pathogenesis. American Society of Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 35.Matsumoto, M., M. Nishiguchi, S. Kikkawa, H. Nishimura, S. Nagasawa, and T. Seya. 1998. Structural and functional properties of complement-activating protein M161Ag, a Mycoplasma fermentans gene product that induces cytokine production by human monocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 273:12407-12414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nicholson, D. M., and N. A. Thornberry. 1997. Caspases: killer proteases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 22:299-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Opitz, O., K. Pietsch, S. Ehlers, and E. Jacobs. 1996-1997. Cytokine gene expression in immune mice reinfected with Mycoplasma pneumoniae: the role of T cell subsets in aggravating the inflammatory response. Immunobiology 196:575-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pietsch, K., S. Ehlers, and E. Jacobs. 1994. Cytokine gene expression in the lungs of BALB/c mice during primary and secondary intranasal infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Microbiology 140:2043-2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rasmussen, S. J., L. Eckmann, A. J. Quayle, L. Shen, Y. Zhang, D. J. Anderson, J. Fierer, R. S. Stephens, and M. F. Kagnoff. 1997. Secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by epithelial cells in response to Chlamydia infection suggests a central role for epithelial cells in chlamydial pathogenesis. J. Clin. Investig. 99:77-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rawadi, G., and S. Roman-Roman. 1996. Mycoplasma membrane lipoproteins induce proinflammatory cytokines by a mechanism distinct from that of lipopolysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 64:637-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rawadi, G., J. Zugaza, B. Lemercier, J. C. Marvaud, M. Popoff, J. Bertoglio, and S. Roman-Roman. 1999. Involvement of small GTPases in Mycoplasma fermentans membrane lipoproteins-mediated activation of macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 274:30794-30798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Razin, S. 1999. Adherence of pathogenic mycoplasmas to host cells. Biosci. Rep. 19:367-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rodwell, A. W., and R. F. Whitcomb. 1983. Methods for direct and indirect measurement of mycoplasma growth, p. 185-196. In S. Razin and J. G. Tully (ed.), Methods in mycoplasmology, vol. I. Mycoplasma characterization. Academic Press, New York, N.Y.

- 44.Schaffner, E., O. Opitz, K. Pietsch, G. Bauer, S. Ehlers, and E. Jacobs. 1998. Human pathogenic Mycoplasma species induced cytokine gene expression in Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-positive lymphoblastoid cell lines. Microb. Pathog. 24:257-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stuart, P. M. 1993. Mycoplasmal induction of cytokine production and major histocompatibility complex expression. Clin. Infect. Dis. 17:S187-S191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thornberry, N. A., H. G. Bull, J. R. Calaycay, K. T. Chapman, A. D. Howard, M. J. Kostura, F. J. Miller, J. Chin, G. J. F. Ding, L. A. Egger, E. P. Gaffney, G. Limjuco, O. C. Palyha, S. M. Raju, A. M. Rolando, J. P. Salley, T.-T. Yamin, T. D. Lee, J. E. Shively, M. MacCross, R. A. Mumford, J. A. Schmidt, and M. J. Tocci. 1992. A novel heterodimeric cysteine protease is required for interleukin-1 beta processing in monocytes. Nature 356:768-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uchida, Y., H. Shiba, H. Komatsuzawa, T. Takemoto, M. Sakata, T. Fujita, H. Kawaguchi, M. Sugai, and H. Kurihara. 2001. Expression of IL-1beta and IL-8 by human gingival epithelial cells in response to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Cytokine 14:152-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ulich, T. R., S. Yin, K. Guo, E. S. Yi, D. Remick, and J. del Castillo. 1991. Intratracheal injection of endotoxin and cytokines. II. Interleukin-6 and transforming growth factor beta inhibit acute inflammation. Am. J. Pathol. 138:1097-1101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang, Y., and S. W. Walsh. 1996. TNF alpha concentrations and mRNA expression are increased in preeclamptic placentas. J. Reprod. Immunol. 32:157-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wingren, A. G., O. Bjorkdahl, T. Labuda, L. Bjork, U. Andersson, U. Gullberg, G. Hedlund, H. O. Sjogren, T. Kalland, B. Widegren, and M. Dohlsten. 1996. Fusion of a signal sequence to the interleukin-1 beta gene directs the protein from cytoplasmic accumulation to extracellular release. Cell. Immunol. 169:226-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolfson, J. S., and D. C. Hooper. 1989. Fluoroquinolone antimicrobial agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2:378-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang, J., and P. J. Duerksen-Hughes. 2001. Activation of a p53-independent, sphingolipid-mediated cytolytic pathway in p53-negative mouse fibroblast cells treated with N-methyl-N-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine. J. Biol. Chem. 276:27129-27135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshida, Y., M. Maruyama, T. Fujita, N. Arai, R. Hayashi, J. Araya, S. Matsui, N. Yamashita, E. Sugiyama, and M. Kobayashi. 1999. Reactive oxygen intermediates stimulate interleukin-6 production in human bronchial epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 276:L900-L908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang, S., D. J. Wear, and S.-C. Lo. 2000. Mycoplasmal infections alter gene expression in cultured human prostatic and cervical epithelial cells. Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 27:43-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]