Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) are professional antigen-presenting cells which initiate and regulate T-cell immune responses. Here we show that murine splenic DCs can be ranked on the basis of their ability to phagocytose and harbor the obligately intracellular parasite Leishmania major. CD4+ CD8− DCs are the most permissive host cells for L. major amastigotes, followed by CD4− CD8− DCs; CD4− CD8+ cells are the least permissive. However, the least susceptible CD4− CD8+ DC subset was the best interleukin-12 producer in response to infection. Infection did not induce in any DC subset production of the proinflammatory cytokine gamma interferon and nitric oxide associated with the induction of Th1 responses. The number of parasites phagocytosed by DCs was low, no more than 3 organisms per cell, compared to more than 10 organisms per macrophage. In infected DCs, the parasites are located in a parasitophorous vacuole containing both major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and lysosome-associated membrane protein 1 molecules, similar to their location in the infected macrophage. The parasite-driven redistribution of MHC class II to this compartment indicates that infected DCs should be able to present parasite antigen.

Leishmania spp. are obligately intracellular parasites of the mononuclear phagocyte system. In a mammalian host, macrophages function both as host cells required for parasite survival and as the effector arm of a successful T-cell-mediated immune response (2). In murine cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania major, susceptibility to disease is critically dependent on the type of T-cell immunity induced by infection. Resistance to infection is associated with the development of a Th1 response, whereas susceptibility is associated with induction of Th2 type responses (23). To date, the mechanisms and molecules that determine the type of immune response induced are not known.

Dendritic cells (DCs) are sentinels that have the ability to detect pathogens, induce T-cell activation, and trigger memory T cells, providing a link between the innate and adaptive immune systems (5, 6, 24). In turn, pathogens have evolved mechanisms to exploit or evade DC biology (24). Not surprisingly, there is evidence that in leishmaniasis, DCs are involved in the initiation and maintenance of T-cell immune responses. However, their precise role in the development and regulation of Th1 or Th2 responses is not known.

A large volume of data has accumulated which shows that DCs are phenotypically and functionally heterogeneous (20). In the mouse spleen three distinct subpopulations of DCs have been identified (27), whereas in skin-draining lymph nodes we recently showed the existence of five subpopulations (14). There is evidence that the three spleen subpopulations are products of separate developmental lineages, have different life spans (17), and, most importantly, may be functionally distinct. Indeed, each of these subsets secretes a different pattern of cytokines (15). Although several studies have shown that L. major or Leishmania mexicana amastigotes can infect cultured skin-derived or bone marrow-derived DCs (7, 10, 25, 26), there has been no characterization of the host cell phenotype. Here, we explore the interactions of the parasite with purified splenic DC subpopulations and show that there are significant differences in response to infection. In macrophages, the phagocytosed parasites reside in a parasite-modified lysosome, the parasitophorous vacuole (PV), with hierarchically restricted access to the extracellular environment. This location is significant in terms of parasite survival, as well as in terms of the ability of the cells to present parasite antigen to T cells (4). In this study we examined for the first time the L. major PV in infected DCs and found that the parasites reside in a lysosome-associated membrane protein 1 (Lamp1)- and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II-positive compartment, similar to the situation in macrophages. However, compared to the number of parasites per macrophage, the number of parasites per DC is much lower.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

C57BL/6 mice were bred under specific-pathogen-free conditions at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute and were subsequently maintained under conventional conditions. They were used when they were 5 to 8 weeks old.

Parasites.

The L. major isolate LRC-L137 (MHOM/IL/67/JerichoII) was obtained from the World Health Organization Reference Center for Leishmaniasis, Jerusalem, Israel, and the virulent cloned line V121 isolated from this stock has been described before (13). Amastigotes were harvested from 4-week-old lesions at the base of the tail of CBA/H nu/nu mice and purified as described by Glaser et al. (11).

Isolation of DCs.

DCs were isolated as described previously (27). Briefly, spleens were cut into small fragments, digested in RMPI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and containing collagenase (1 mg/ml; type II; Worthington Biochemical, Freehold, N.J.) and DNase (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany), and then treated for 5 min with EDTA to disrupt T-cell-DC complexes. All subsequent procedures were performed at 0 to 4°C in a Ca2+- and Mg2+-free medium. Low-density cells (<1.077g/cm3 at mouse osmolarity at 4°C) were selected by centrifugation in a Nycodenz medium. Cells that were not of the DC lineage were then depleted by incubating the cells with previously optimized amounts of anti-CD3 (KT3), anti-Thy1 (T24/31.7), anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), anti-Gr-1 (RB6-8C5), and anti-erythrocyte (TER-119) and then removing the antibody-binding cells with anti-rat immunoglobulin-coupled magnetic beads (Dynabeads; Dynal, Oslo, Norway). The preparation was then used directly for immunofluorescence labeling prior to positive sorting by flow cytometry. The cell viability was more than 95% after purification.

Immunofluorescence labeling of DCs and isolation by flow cytometry.

The monoclonal antibodies, the fluorescent conjugates, and the multicolor labeling procedures used have all been described previously (27). To identify and sort all DCs, the pan-DC markers used were high levels of MHC class II or CD11c. Anti-MHC class II (M5/114) and anti-CD11c (N418) were used as fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugates, anti-CD4 (GK1.5) was used as a phycoerythrin conjugate, and anti-CD8α (YTS169.4) was used as a Cy5 conjugate. Sorting was performed with a Moflo instrument (Cytomation Inc.). Gating on propidium iodide-labeled cells allowed exclusion of dead cells and autofluorescent cells.

Infection of DCs.

After sorting, DC subpopulations were suspended in RPMI 1640 medium at a concentration of 106 cells/ml, and 100 μl was added to each well of 96-well plates. Amastigotes at a ratio of 10:1 were added to the wells, and the plates were incubated overnight. The cells were washed three times in EDTA-balanced salt solution supplemented with 10% FBS. After suspension at a concentration of 106 cells/ml in medium, the cells were placed on coverslips coated with anti-MHC class II antibodies and incubated for 1 to 2 h at 37°C in 10% CO2 in order to promote adherence to glass and spreading. The cells were washed three times in warm phosphate-buffered saline (PBS); then they were fixed with methanol and stained with Wright-Giemsa stain or fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained for immunofluorescence as described below.

Infection of macrophages.

To identify and sort peritoneal macrophages, the marker used was high-level expression of the surface marker F4/80. Peritoneal cells were washed and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-F4/80. After sorting and suspension in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with FBS, cells were plated onto sterile coverslips in 24-well plates. Then 105 macrophages were seeded onto each coverslip and allowed to adhere for 1 to 2 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. V121 amastigotes were added to macrophage monolayers at a ratio of 10:1 and incubated overnight. The cells were washed twice in warm PBS, fixed with methanol, and stained with Wright-Giemsa stain. The infection rate and number of parasites per cell were estimated by counting at least 200 cells in duplicate samples.

Stimulation of isolated DCs for cytokine production.

Sorted splenic DCs (1 × 105 to 2 × 105 cells) were cultured in 200 μl of modified RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS in 96-well round-bottom plates at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 10% CO2 in air. For interleukin-12 (IL-12) production, the stimulation mixture consisted of cytokines, microbial stimulus, or freshly purified L. major amastigotes. The cytokines used were granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (200 U/ml), gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (20 ng/ml), and IL-4 (100 U/ml), as indicated below (see Fig. 4). The other stimuli used were CpG-phosphorothioate (0.5 mM) and L. major amastigotes (parasite-to-cell ratio, 10:1). The supernatants were collected after 24 h. For IFN-γ production the stimuli used were IL-12, IL-18 (1 ng/ml), and L. major amastigotes (parasite-to-cell ratio, 10:1) (see Fig. 5). The supernatants were collected after 72 h.

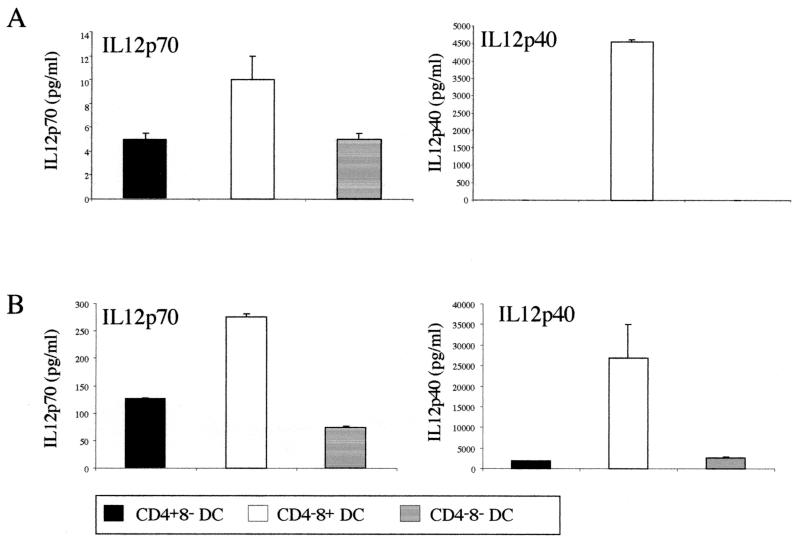

FIG. 4.

IL-12 (p70 and total p40 present in p70 heterodimers and p40 homodimers) production by the different DC subpopulations infected with L. major amastigotes. A total of 1 × 105 purified DCs were incubated with 1 × 106 L. major amastigotes. After 24 h, supernatants were collected to determine the cytokine production by ELISA. Results of two representative experiments (A and B) are shown.

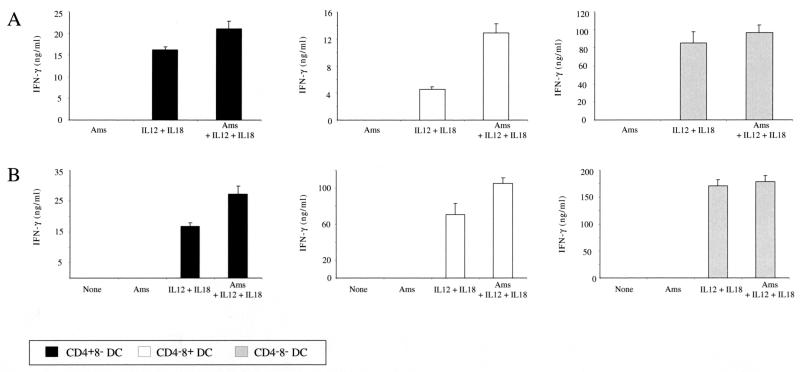

FIG. 5.

IFN-γ production by different DC subsets in response to cytokine or amastigote stimulation. A total of 1 × 105 purified DCs were incubated with 1 × 106 L. major amastigotes (Ams) in the presence or absence of IL-12 and IL-18. After 72 h, supernatants were collected to determine the cytokine production by ELISA. Results of two representative experiments (A and B) are shown.

Analysis of IL-12 and IFN-γ by ELISA.

The production of cytokines in the DC culture supernatants was determined by a capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Briefly, 96-well polyvinyl chloride microtiter plates (Dynatech Laboratories, Chantilly, Va.) were coated with appropriate purified capture monoclonal antibodies, including R2-9A5 (anti-IL-12p70; hybridoma obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.), C15.6 (anti-IL-12p40; PharMingen), and RA-6A4 (anti-IFN-γ; American Type Culture Collection). Cytokine binding was then detected with appropriate biotinylated detection monoclonal antibodies, including C17.8 (anti-IL-12 p40 and p70; hybridoma provided by L. Schofield, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute) and XMG1.2 (anti-IFN-γ; American Type Culture Collection). Binding of the second antibody was detected with streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom), followed by a substrate solution containing 548 mg of 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid) (ABTS) (Sigma-Aldrich) per ml and 0.001% hydrogen peroxide (Ajax Chemicals, Aubern, Australia) in 0.1 M citric acid (pH 4.2). The optical densities at 405 to 490 nm of the samples were determined with an ELISA plate reader.

Detection of NO.

Nitric oxide (NO) production by DCs stimulated with the preparations described above was determined by assaying the stable end product NO2− using the Griess reaction. Portions (100 μl) of 48-h culture supernatants were each incubated with 100 μl of Griess reagent (0.05% nephthylethylenediamine, 0.5% sulfanilimide, 2.5% H3PO4) at room temperature for 10 min. The color reaction was read with an ELISA plate reader at 490 to 650 nm. Concentrations of NO in the samples were calibrated with a sodium nitrite reference standard.

Immunofluorescence and confocal laser microscopy.

After fixation in paraformaldehyde, cells were washed and incubated with 0.05% saponine-PBS to allow permeabilization. The following antibodies used for immunofluorescence were diluted with 0.05% saponine-10% normal goat serum-PBS: anti-MHC class II (biotin-conjugated N22), anti-Lamp1 (Pharmingen), anti-cystatin C, and anti-Leishmania lipophosphoglycan (WIC79-3-FITC). For detection, streptavidin-Texas Red-, streptavidin-FITC-, or Texas Red-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-rat immunoglobulin G preparations (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were used. The stained cells were visualized by confocal laser microscopy after they were mounted in the DAKO fluorescence mounting medium supplemented with diazabicyclo-2,2,2-octane (Sigma Chemical Co.)

Electron microscopy.

L. major-infected DCs were pelleted and fixed overnight at 4°C in 2% paraformaldehyde-2% glutaraldehyde in PBS. Cells were washed five times in PBS, embedded in 2% agarose, and postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 h at room temperature. Agar blocks were washed overnight in water and dehydrated in a graded acetone series (10 to 100%) before they were embedded in Spurr's resin. The sections were stained with lead citrate for examination by transmission electron microscopy.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Uptake of Leishmania amastigotes by splenic DCs and intracellular location of the parasites.

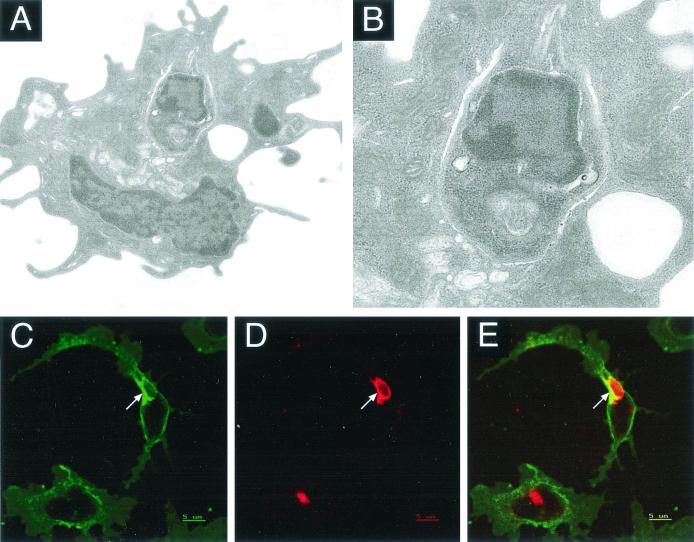

Infection of fetal skin-derived or bone marrow-derived DCs by L. mexicana amastigotes has been described previously (7, 25, 26), as has L. major infection of cells presumed to be epidermal DCs (8, 10). However, infection of purified splenic DCs by amastigotes has not been investigated previously. In our initial experiments we examined the ability of L. major amastigotes to infect DCs freshly isolated from the spleen. DCs isolated by flow cytometry from the spleen (27) were incubated overnight with amastigotes at a ratio of parasites to DCs of 10:1. Electron microscopy after overnight culture of DCs with parasites (Fig. 1A) indicated that spleen DCs contained intracellularly located amastigotes. It is generally accepted that receptor-mediated phagocytosis is the mechanism of parasite internalization by macrophages. As a result, the parasite is initially located in a phagosome, which fuses with secondary lysosomes to form a phagolysosome or a PV (4, 12). Although in the studies mentioned above the authors described infection of DCs by Leishmania, the cellular compartment containing the parasite has not been examined previously. In infected splenic DCs, the PV membrane is visible around most of the parasite membrane, especially at the posterior pole of the parasite, whereas at the anterior pole, where the flagellar pocket is located, it is not possible to distinguish between the parasite and the PV membranes. The space between the parasite membrane and the vacuole membrane is not clearly visible, suggesting that the parasite is bound to the membrane (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Detection by electron microscopy and immunofluorescence of L. major amastigote-infected splenic DCs. Purified spleen DCs were incubated with L. major amastigotes at a parasite-to-cell ratio 10:1 for 24 h and analyzed by electron microscopy (A and B) or by confocal laser microscopy using antibodies to Lamp1 (D) or MHC class II (C). In panel E, the red fluorescence and green fluorescence for Lamp1 and MHC class II are superimposed. Infected cells were washed, incubated on anti-MHC class II-coated coverslips, fixed, and permeabilized before they were stained with biotinylated anti-MHC class II, followed by streptavidin-FITC and rabbit anti-Lamp1 antibodies and then Texas Red-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G.

The nature of the intracellular location of the parasites was further studied by immunofluorescence. Because the DCs used in our experiments are not adherent to the plastic used, the cells were incubated on coverslips coated with anti-MHC class II antibodies before fixation and staining. This step allowed adherence as well as spreading of the cells and made the PV stand out. In order to characterize the PV, we used antibodies to Lamp1, as well as anti-cystatin C and anti-MHC class II antibodies. Analysis by confocal laser microscopy showed that parasites were located in a Lamp1-positive compartment, suggesting that the phagosome had fused with lysosomes (Fig. 1D). In these cells, MHC class II molecules were also detected on the membrane of the PV (Fig. 1C). In contrast to the situation in normal uninfected DCs, where there is no apparent colocalization of Lamp1 and MHC class II molecules, there was clear colocalization of these two molecules in the PV (Fig. 1D and E) suggesting that there was a redistribution of the MHC class II molecules due to the presence of parasites. The PV also harbored cystatin C molecules (data not shown). There is evidence that infection of in vitro-cultured skin-derived Langerhans cells leads to an increase in the synthesis of MHC class II molecules, which are normally downregulated upon culture in vitro (10).

The presence of MHC class II molecules and cystatin C in the compartment which harbors the parasites, in combination with increased synthesis of MHC class II, suggests but does not prove that the infected DCs may be able to process and present parasite antigen to naïve T cells.

Comparison of parasite uptake by splenic DCs and macrophages.

The uptake of amastigotes by freshly purified splenic DCs is not as efficient as the uptake of parasites by macrophages. We compared the parasite uptake by splenic DCs and resident peritoneal macrophages or the J774 macrophage cell line. We found that only 25 to 40% of splenic DCs harbored parasites, whereas more than 85% of the macrophages were infected under the same conditions. Not only was a higher percentage of macrophages infected, but each cell engulfed a significantly higher number of parasites. Indeed, while each splenic DC harbored, on average, 1 to 2 parasites, each peritoneal macrophage harbored more than 10 parasites after overnight culture. This suggests that the macrophage may be the preferential target cell for parasites, and it certainly is the most abundant cell in infected tissues. Since the DC life span is relatively short (17), it is unlikely that parasites spend sufficient time in infected DCs to be able to replicate, unless infection suppresses cell death and prolongs the DC life span (22). It is possible that residence in a DC leads to a state of parasite latency and promotes the development of the persistent or quiescent parasite known to survive in an immune individual in the presence of a strong protective immune response (1).

In terms of the ability of infected DCs to initiate T-cell responses, it is not known what the optimal time of pathogen residence or survival in a DC is for activation and subsequent interaction with T cells or other cells.

DC subpopulations show different susceptibilities to infection with L. major amastigotes.

Mouse splenic DCs are heterogeneous, as determined by the expression of CD4 and CD8α molecules on their surfaces. The three subpopulations of splenic DCs showed similar mature but unactivated phenotypes, as determined by expression of MHC class II, CD40, CD80, and CD86 markers (17). Despite this phenotype, in vivo and in vitro studies of the phagocytic capacities of these subpopulations performed with latex beads showed that a high proportion of all three populations (CD4+ CD8−, CD4− CD8+, and CD4− CD8−) had the capacity to take up latex beads, and the CD4− CD8+ population showed the lowest proportion of phagocytic cells (17).

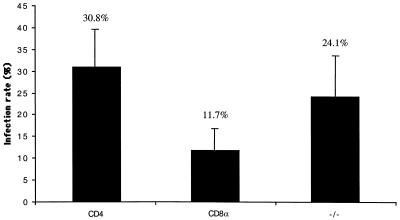

The uptake of L. major parasites by splenic DCs has been addressed only once previously, in a study performed with total splenic DCs and promastigotes, the developmental form which is present in the sandfly and which initiates infection in the mammalian host. Here, the uptake of L. major amastigotes, the developmental form that is present in the mammalian host and is responsible for the disease, by the three splenic DC subsets was investigated. The splenic DC subsets, CD4+ CD8−, CD4− CD8−, CD4− CD8+, were purified from naïve C57BL/6 mice and incubated with freshly purified L. major amastigotes at a parasite-to-cell ratio of 10:1. After overnight culture, the cells were washed to remove free parasites, incubated on coverslips coated with anti-MHC class II antibody, and stained with Giemsa stain. Amastigote uptake was determined by microscopic examination of at least 200 cells. As shown in Fig. 2, of the three populations, the CD4+ CD8− DCs showed the greatest uptake of amastigotes, followed by the CD4− CD8− DCs, which were significantly (P < 0.05) less infected; the CD4− CD8+ DCs showed the lowest level of parasite uptake, and the value was significantly different from the values obtained for CD4+ CD8− DCs (P < 0.0001) and CD4− CD8− DCs (P < 0.0005). This hierarchy of susceptibility was not due to differences in the degrees of maturation of the three populations, which were similar as determined by expression of MHC class II, CD40, CD80, and CD86 (data not shown). New data are starting to shed light on mechanisms by which some mature DCs in lymphoid organs maintain the ability to capture and process antigen (9). The observation that splenic DC subpopulations display a hierarchy of susceptibility to infection may also apply to DCs in the skin-draining lymph nodes, which contain a similar complement of DCs and which may be important in cutaneous leishmaniasis (14).

FIG. 2.

Differential infection of splenic DC subpopulations by L. major amastigotes. Purified CD4+ CD8−, CD4− CD8+, and CD4− CD8− DCs were incubated with freshly purified L. major amastigotes at a parasite-to-cell ratio of 10:1. After overnight culture, cells were washed and incubated for 2 to 3 h on anti-MHC class II antibody (N22)-coated coverslips before fixation and staining with Giemsa stain. The infection rate was determined by microscopic examination of at least 200 cells in duplicate samples. The results of one experiment that is representative of six experiments are shown. The statistical analysis included the results of seven independent experiments.

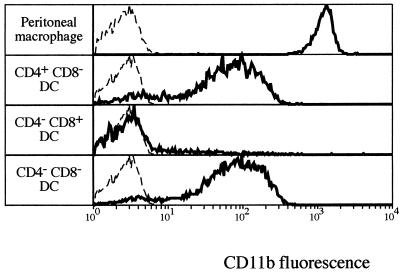

Attachment and uptake of parasites by macrophages have been well characterized and involve direct binding of parasite ligands to macrophage receptors and indirect binding after opsonization of the parasite by complement components (2, 3). A variety of macrophage receptors involved in the entry of Leishmania promastigotes have been described, including the mannose-fucose receptor, the receptor for advanced glycosylation end products, the fibronectin receptor, the Fc receptor, and the complement receptors CR1 and CR3 (also called CD11b). Despite the fact that Leishmania amastigotes are responsible for disease, the molecules involved in their entry into macrophages have been less well characterized. Although recent evidence indicates that the Fc receptor is important in sustaining L. mexicana infection in mice (18), this may be relevant only late in infection and mainly in susceptible mice or humans who display detectable antibodies and not in more resistant individuals who do not show significant antibody levels. In this case, the complement receptors may play a major role in invasion. We therefore examined the expression of CD11b molecules on the different DC populations and compared the DC populations to macrophages in the context of the ability to become infected with amastigotes.

As shown in Fig. 3, peritoneal macrophages, which have an infection rate of more than 85% after overnight culture, also express the highest level of CD11b at the surface. In contrast, CD4+ CD8− DCs, which have an infection rate of about 50%, and CD4− CD8− DCs, which have an infection rate of about 40%, express 10 times less CD11b on their surfaces. CD4− CD8+ DCs, which have the lowest infection rate (about 15%), do not express detectable CD11b on their surfaces, suggesting that CD11b could be at least one of the major receptors on DCs for the L. major amastigotes. Inhibition of invasion by F(ab)2 fragments of a receptor-blocking antibody, such as 5C6, should elucidate the role of this receptor. In addition, the roles of molecules such as the mannose-fucose receptor and CR1 need to be examined.

FIG. 3.

Differential CD11b expression by peritoneal macrophages and splenic DC subsets. Peritoneal cells were washed, and the population of F4/80-positive cells considered to be macrophages was selected. DCs isolated from spleens were first gated on MHC class II- and Cy5-positive cells and then selected for expression of CD4 or CD8 in the FITC channel. CD11b expression was assessed by using phycoerythrin-conjugated M1/70 antibody.

Effect of infection on splenic DC maturation.

One of the questions addressed in our study was the effect of infection on the maturation of splenic DCs. It is known that overnight incubation of splenic DCs causes spontaneous maturation, increasing the expression of MHC class II, CD40, CD80, and CD86 molecules on the surface. In this study we did not observe any effect due to the presence of amastigotes for any of the DC subsets (data not shown).

Effect of infection on cytokines and NO production by DCs.

Recent work has shown that differential expression of CD4 and CD8 molecules correlated with major differences in the capacities of DC subpopulations to produce cytokines (15). In intracellular infections such as leishmaniasis, resistance to disease correlates with induction of a polarized Th1 immune response. As IL-12 and IFN-γ are major players in the induction of Th1 responses, production of these cytokines by infected DCs was examined.

In the presence of amastigotes, the CD4− CD8+ DC subset showed an increase in IL-12 production (Fig. 4). However, the IL-12 production by amastigote-infected DCs was low compared to that induced by strong stimuli, such as CpG, IFN-γ, and IL-4 (15), and addition of amastigotes to a cocktail of CpG, IL-4, and IFN-γ had no effect on the level of IL-12p70 or IL-12p40 (data not shown). However, amastigotes increased the amount of IL-12p40 produced by the CD4− CD8+ subpopulation. As this DC population is also the population which produces more bioactive p70, it probably keeps the ratio of p70 to p40 constant. It may be significant that the CD4− CD8+ DCs are the DCs that are infected least by Leishmania amastigotes.

In the presence of amastigotes alone, none of the splenic DC subsets could produce IFN-γ (Fig. 5). However, when DCs were stimulated with IL-12 plus IL-18, we observed strong IFN-γ production which was slightly upregulated in the presence of amastigotes, suggesting that there was positive feedback due to IL-12 production by these cells. This upregulation was more apparent in the CD4− CD8+ DCs, which are the best producers of IL-12.

NO is an important toxic effector molecule in the regulation of host defense and immunity and has been shown to be produced by bone marrow-derived DCs upon IFN-γ and endotoxin stimulation (21). Moreover, NO production is considered the major effector mechanism leading to the intracellular killing of L. major in infected macrophages (19). Under our experimental conditions, no NO production was detected in any of the different DC subsets in the presence of L. major amastigotes and/or other stimuli, such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, or CpG (data not shown).

Concluding remarks.

A key feature of the immune responses induced by various microbial infections is plasticity in both the type and the magnitude of the response to individual organisms (16). Interaction between phenotypically and functionally heterogeneous antigen-presenting DCs and naïve T cells in the spleen and lymph nodes shapes the type and magnitude of this response. In leishmaniasis, this interaction may determine the disease manifestations depending on whether it leads to differentiation of a host-protective Th1 or a disease-exacerbating Th2 type of T cell. The studies presented here suggest that the microbe may influence the type of DCs that the naïve T cells interact with in the T-cell-rich area of the spleen and possibly the skin-draining lymph nodes. Thus, the intracellular amastigotes of Leishmania preferentially infect the CD4+ CD8− DC subpopulation and not the CD4− CD8+ cells best able to produce the proinflammatory cytokine IL-12 involved in the host-protective Th1 responses (Table 1). In addition, we found that the parasite is localized to an intracellular compartment containing Lamp1, MHC class II, and cystatin C, suggesting that the infected DCs should be able to present parasite antigen to T cells. The immunological consequences of the parasites' interactions with the specific DC populations is the subject of current work. In addition, in current experiments we aim to examine the interactions of amastigotes with DC subpopulations in vivo during the course of L. major infections in genetically resistant and susceptible mice which display polarized Th1 or Th2 immune responses.

TABLE 1.

DC type, L. major infection, and cytokine production

| DC type | Infection level | CD11b expression | IL-12 production | IFN-γ production |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ CD8− | +++ | + | + | − |

| CD4− CD8− | ++ | + | + | − |

| CD4− CD8+ | +− | − | ++ | − |

Acknowledgments

We thank V. Lapatis, J. Chan, D. Kaminaris, F. Battye, and C. Tarlinton for assistance with flow cytometry and Ingrid Bonig for the electron microscopy.

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and by the UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR).

Editor: J. M. Mansfield

REFERENCES

- 1.Aebischer, T., S. F. Moody, and E. Handman. 1993. Persistence of virulent Leishmania major in murine cutaneous leishmaniasis: a possible hazard for the host. Infect. Immun. 61:220-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander, J., and D. G. Russell. 1992. The interaction of Leishmania species with macrophages. Adv. Parasitol. 31:175-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander, J., A. R. Satoskar, and D. G. Russell. 1999. Leishmania species: models of intracellular parasitism. J. Cell Sci. 112:2993-3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antoine, J. C., E. Prina, T. Lang, and N. Courret. 1998. The biogenesis and properties of the parasitophorous vacuoles that harbour Leishmania in murine macrophages. Trends Microbiol. 6:392-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banchereau, J., F. Briere, C. Caux, J. Davoust, S. Lebecque, Y. J. Liu, B. Pulendran, and K. Palucka. 2000. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18:767-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banchereau, J., and R. M. Steinman. 1998. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392:245-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett, C. L., A. Misslitz, L. Colledge, T. Aebischer, and C. C. Blackburn. 2001. Silent infection of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells by Leishmania mexicana amastigotes. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:876-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blank, C., H. Fuchs, K. Rappersberger, M. Rollinghoff, and H. Moll. 1993. Parasitism of epidermal Langerhans cells in experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis with Leishmania major. J. Infect. Dis. 167:418-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouchon, A., C. Hernandez-Munain, M. Cella, and M. Colonna. 2001. A DAP12-mediated pathway regulates expression of CC chemokine receptor 7 and maturation of human dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 194:1111-1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flohe, S., T. Lang, and H. Moll. 1997. Synthesis, stability, and subcellular distribution of major histocompatibility complex class II molecules in Langerhans cells infected with Leishmania major. Infect. Immun. 65:3444-3450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glaser, T. A., S. J. Wells, T. W. Spithill, J. M. Pettitt, D. C. Humphris, and A. J. Mukkada. 1990. Leishmania major and L. donovani: a method for rapid purification of amastigotes. Exp. Parasitol. 71:343-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Handman, E. 1999. Cell biology of Leishmania. Adv. Parasitol. 44:1-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Handman, E., R. E. Hocking, G. F. Mitchell, and T. W. Spithill. 1983. Isolation and characterization of infective and non-infective clones of Leishmania tropica. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 7:111-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henri, S., D. Vremec, A. Kamath, J. Waithman, S. Williams, C. Benoist, K. Burnham, S. Saeland, E. Handman, and K. Shortman. 2001. The dendritic cell populations of mouse lymph nodes. J. Immunol. 167:741-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hochrein, H., K. Shortman, D. Vremec, B. Scott, P. Hertzog, and M. O'Keeffe. 2001. Differential production of IL-12, IFN-alpha, and IFN-gamma by mouse dendritic cell subsets. J. Immunol. 166:5448-5455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jankovic, D., Z. Liu, and W. C. Gause. 2001. Th1- and Th2-cell commitment during infectious disease: asymmetry in divergent pathways. Trends Immunol. 22:450-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamath, A. T., J. Pooley, M. A. O'Keeffe, D. Vremec, Y. Zhan, A. M. Lew, A. D'Amico, L. Wu, D. F. Tough, and K. Shortman. 2000. The development, maturation, and turnover rate of mouse spleen dendritic cell populations. J. Immunol. 165:6762-6770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kima, P. E., S. L. Constant, L. Hannum, M. Colmenares, K. S. Lee, A. M. Haberman, M. J. Schlomchik, and D. McMahon-Pratt. 2000. Internalization of Leishmania mexicana complex amastigotes via the Fc receptor is required to sustain infection in murine cutaneous leishmaniasis. J. Exp. Med. 191:1063-1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liew, F. Y., X. Q. Wei, and L. Proudfoot. 1997. Cytokines and nitric oxide as effector molecules against parasitic infections. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 352:1311-1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu, Y. J. 2001. Dendritic cell subsets and lineages, and their functions in innate and adaptive immunity. Cell 106:259-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu, L., C. A. Bonham, F. G. Chambers, S. C. Watkins, R. A. Hoffman, R. L. Simmons, and A. W. Thomson. 1996. Induction of nitric oxide synthase in mouse dendritic cells by IFN-gamma, endotoxin, and interaction with allogeneic T cells: nitric oxide production is associated with dendritic cell apoptosis. J. Immunol. 157:3577-3586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore, K. J., and G. Matlashewski. 1994. Intracellular infection by Leishmania donovani inhibits macrophage apoptosis. J. Immunol. 152:2930-2937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reiner, S. L., and R. M. Locksley. 1995. The regulation of immunity to Leishmania major. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 13:151-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rescigno, M., and P. Borrow. 2001. The host-pathogen interaction: new themes from dendritic cell biology. Cell 106:267-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Stebut, E., Y. Belkaid, T. Jakob, D. L. Sacks, and M. C. Udey. 1998. Uptake of Leishmania major amastigotes results in activation and interleukin 12 release from murine skin-derived dendritic cells: implications for the initiation of anti-Leishmania immunity. J. Exp. Med. 188:1547-1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Stebut, E., Y. Belkaid, B. V. Nguyen, M. Cushing, D. L. Sacks, and M. C. Udey. 2000. Leishmania major-infected murine langerhans cell-like dendritic cells from susceptible mice release IL-12 after infection and vaccinate against experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:3498-3506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vremec, D., J. Pooley, H. Hochrein, L. Wu, and K. Shortman. 2000. CD4 and CD8 expression by dendritic cell subtypes in mouse thymus and spleen. J. Immunol. 164:2978-2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]