Abstract

Due to its small size, rapid generation time, powerful genetic systems, and genomic resources, the zebrafish has emerged as an important model of vertebrate development and human disease. Its well-developed adaptive and innate cellular immune systems make the zebrafish an ideal model for the study of infectious diseases. With a natural and important pathogen of fish, Streptococcus iniae, we have established a streptococcus- zebrafish model of bacterial pathogenesis. Following injection into the dorsal muscle, zebrafish developed a lethal infection, with a 50% lethal dose of 103 CFU, and died within 2 to 3 days. The pathogenesis of infection resembled that of S. iniae in farmed fish populations and that of several important human streptococcal diseases and was characterized by an initial focal necrotic lesion that rapidly progressed to invasion of the pathogen into all major organ systems, including the brain. Zebrafish were also susceptible to infection by the human pathogen Streptococcus pyogenes. However, disease was characterized by a marked absence of inflammation, large numbers of extracellular streptococci in the dorsal muscle, and extensive myonecrosis that occurred far in advance of any systemic invasion. The genetic systems available for streptococci, including a novel method of mutagenesis which targets genes whose products are exported, were used to identify several mutants attenuated for virulence in zebrafish. This combination of a genetically amenable pathogen with a well-defined vertebrate host makes the streptococcus-zebrafish model of bacterial pathogenesis a powerful model for analysis of infectious disease.

An infectious disease is the manifestation of a dynamic series of events that occur between the host and pathogen that are defined by the interaction of pathogen-expressed virulence factors and the surveillance and defense systems of the host. Expression of both host and pathogen components is highly coordinated, and the stimulus for any given response by the pathogen is often a prior change in defense gene expression by the host. This dynamic interplay determines the character, course, and outcome of the pathogenic process. Much remains to be elucidated about host-pathogen interactions at the molecular level, and the most informative model systems are likely to be those in which both the pathogen and host are amenable to genetic analysis. Unfortunately, while considerable progress has been made in the development of genetic systems for a wide variety of pathogenic microorganisms, rather less progress has been made in the host organisms that have traditionally been used to model infectious diseases of humans.

Recently, an exciting approach has been to make use of the abilities of certain bacterial pathogens to infect nonmammalian model organisms with well-defined genetic systems, including the invertebrates Drosophila melanogaster (15, 35, 55) and Caenorhabditis elegans (14, 42) and the plant Arabidopsis thaliana (52). This approach has been widely successful in identification of pathogen genes that support virulence (51) and host genes involved in sensing and clearing infections (50). The ability of these models to provide insight into infection of mammals is derived from the fact that many fundamental host defense strategies are evolutionarily ancient and are conserved among diverse taxa, as are the microbial virulence factors used to evade these defenses (63). However, these model organisms lack defense systems that play important roles in mammalian host-pathogen interactions, including leukocytes, innate cellular immunity, and adaptive immune systems.

In contrast, the zebrafish (Danio rerio) has a well-developed immune system with many similarities to mammalian systems (49, 66), and its highly developed genetics, small size, and rapid generation time have made it an important model for analysis of vertebrate development (61), including development of the immune system (66). More recent efforts, including ongoing genomic sequencing (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/D_rerio/) and expressed sequence tag projects (4), have identified numerous orthologs of human genes and have suggested that the zebrafish can be used in functional analyses of these genes as models of human disease (75).

The development of zebrafish as a model of bacterial infectious disease will require a suitable pathogen. For comparison to human disease, the ideal pathogen would be highly adapted to cause a naturally occurring disease in fish but also be capable of causing disease in humans. The bacterium should grow readily under laboratory conditions, cause acute disease, and have the potential for development of a genetic system. The bacterium should be representative of a group of organisms that are important human pathogens, and the host-parasite relationship should involve both innate and adaptive immunity. One bacterium that meets all these criteria is the gram-positive organism Streptococcus iniae, a pathogen of both fish and humans. Originally identified from subcutaneous abscesses on Amazon freshwater dolphins (47, 48), S. iniae has been reported to cause disease in more than two dozen species of fish from both freshwater and saltwater environments (5, 16, 18, 37, 45). More recently, S. iniae has been recognized as one of the most serious causes of disease in fish raised in aquaculture, causing 30 to 50% mortality in affected fishponds (34, 74), and is capable of causing disease in humans who have recently handled infected fish from aquaculture farms (69, 70).

Similar to the streptococcal species that are pathogenic for humans, S. iniae grows readily under laboratory conditions and causes acute illness that is characterized by a strong inflammatory response by the host. In fish, the most common presentation of S. iniae disease is meningoencephalitis (7, 16, 17), and bacteria can be isolated in large numbers from the central nervous system of infected fish (20). Systemic invasive infection is also common, often involving multiple organs and sepsis (9, 17, 74). In this regard, infection of fish by S. iniae resembles infection of humans by several streptococcal species, including S. agalactiae (group B streptococcus) (3, 58, 59) and S. pneumoniae (26, 27, 54). The bacterium may colonize the surface and/or wounds on fish, and skin erosion and necrotizing dermatitis are not uncommon and may precede invasive disease (21). Soft tissue disease, including cellulitis of the hand, is also the most common manifestation of S. iniae infection in humans (69, 70), which may be promoted by wounding incurred during the handling and preparation of fish (69). Cellulitis caused by S. iniae resembles that caused by S. pyogenes (group A streptococcus), which can also cause other diseases in soft tissues, including pharyngitis, necrotizing faciitis, and myositis (8, 62).

The pathogenesis of streptococcal infection remains poorly understood despite the facts that a large number of streptococcal virulence genes have been identified and that the streptococci remain a major cause of human disease. As gram-positive bacteria, streptococci lack many of the structures and molecules, most notably lipopolysaccharide, that have been shown to play key roles in infection by gram-negative bacteria. However, a common virulence theme among the various human pathogenic species is that they possess mechanisms to evade the innate cellular defenses that are elicited as a component of the host's intense inflammatory response to streptococcal infection. Furthermore, streptococci typically cause damage to tissue while growing in extracellular host compartments, and it appears that an adaptive immune response resulting in the generation of antibody is a key element leading to the resolution of the infection. Their ability to cause acute infection, to evade innate immunity, to be genetically manipulated, and to engage the adaptive arm of the immune response makes the streptococci ideal models for understanding the pathogenesis of acute gram-positive bacterial infections.

In the present study, we report the establishment of a streptococcus-zebrafish model of bacterial pathogenesis. Infection of zebrafish with S. iniae reproduces many of the features observed both in infection of cultured fish populations and in important human infections caused by a variety of streptococcal pathogens, several of which can cause life-threatening systemic disease. We also show that the manifestation of disease in the zebrafish by a human-specific streptococcal pathogen, S. pyogenes, has similarity to soft tissue diseases caused by this pathogen in humans. Analysis of several existing and newly generated streptococcal mutants suggests that zebrafish will be useful for providing insight into human streptococcal disease. Taken together, these results demonstrate the utility of using zebrafish to model host-pathogen relationships in bacterial infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

Transposon delivery plasmids (see below) were maintained in Escherichia coli DH5α. Streptococcal strains included S. iniae 9117 (24), a human clinical isolate from the blood of a patient with cellulitis; S. pyogenes HSC5 (31); and a ropB mutant (HSC101) derived from HSC5 (41). A spontaneous streptomycin-resistant derivative of 9117 was isolated and named 9117C. The identity of S. iniae strains was confirmed by PCR with primers specific for S. iniae 16S rRNA sequences (74). Streptococcal strains were cultured in Todd-Hewitt medium (BBL) supplemented with 0.2% yeast extract (Difco) and 2% proteose peptone (Difco) (THY+P). All streptococci were cultured in airtight sealed tubes without agitation at 37°C. Luria-Bertani medium was used for culture of E. coli strains. Solid media were made by supplementing liquid media with Bacto agar (Difco) to a final concentration of 1.4%. When appropriate, antibiotics were added at the following concentrations: streptomycin, 1 mg/ml for S. iniae, and kanamycin, 25 μg/ml for E. coli and 500 μg/ml for S. pyogenes.

Generation and analysis of mutant streptococcal strains.

Mutagenesis utilized a transposon modified to detect mutations in genes whose products are exported from the bacterial cell (25), thereby allowing the construction of a library of mutants defective for those molecules that are the most likely to interact directly with the host. Isolation of mutations in genes encoding proteins that are exported from the bacterium was conducted with TnFuZ (fusions to phoZ, described in reference 25) as follows. Plasmid pCMG8 containing TnFuZ (25) was purified from E. coli with an anion exchange resin (Concert; Gibco-BRL) and used to transform S. pyogenes by electroporation as described previously (11). The resulting kanamycin-resistant transformants were screened for expression of alkaline phosphatase activity as described elsewhere (25, 44). Expression of alkaline phosphatase activity indicated that TnFuZ had inserted into an open reading frame whose protein product contains an N-terminal secretion signal, identifying genes whose protein products are exported from the bacterium (25).

For analysis of selected TnFuZ insertions, chromosomal DNA prepared by the method of Caparon and Scott (11) was sheared through a 21-gauge needle and used directly as the template in DNA sequencing reactions as described previously (25). Comparison of the sequences to the streptococcal genome database (23) was used to obtain sequences of the entire targeted open reading frames, which were then compared to the Entrez nucleotide sequence database (www.ncbi.nlm.gov/BLAST) with TBLASTN (1).

Zebrafish.

Care and feeding of zebrafish followed established protocols (71) (also see http://zfin.org/zf_info/zfbook/zfbk.html). Zebrafish were anesthetized with Tris-buffered tricaine (3-aminobenzoic acid ethylester, pH 7.0; Sigma) at a concentration of 168 μg/ml by standard methods (71). Prior to injection (see below), anesthetized fish were briefly rinsed in sterile deionized water. Euthanasia of zebrafish used Tris-buffered tricaine at a concentration of 320 μg/ml. Male breeder stock zebrafish (approximately 3.0 to 4.0 cm in length) were obtained from a commercial supplier (Scientific Hatcheries, Huntington Beach, Calif.) and allowed to acclimate for at least 3 days before use. Following infection, zebrafish were housed in sterilized 400-ml beakers (four to six fish per beaker) in 225 ml of sterilized deionized water supplemented with aquarium salts (Instant Ocean; Aquarium Systems, Mentor, Ohio) at a concentration of 60 mg/liter. Beakers were fitted with a perforated cover and housed in an incubator with a transparent door to allow access to ambient light and maintained at 29°C. Zebrafish were not fed for the duration of the experiment (typically less than 48 h).

Preparation of streptococci.

Overnight cultures of streptococci were diluted 1:100 in fresh THY+P, incubated at 37°C, and harvested in the logarithmic phase of growth when the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.300 (corresponding to 108 CFU/ml). Streptococcal cells were washed once in fresh THY+P, resuspended to the original volume in fresh THY+P, and diluted to the appropriate concentration in THY+P. The final concentration of bacteria was confirmed by plating serial dilutions on solid media. Selected streptococcal cultures were killed by exposure to heat (95°C, 30 min), which reduced the number of viable organisms to undetectable levels (<10 CFU/ml).

Infection of zebrafish.

Groups of zebrafish (typically six fish per group) were injected either intramuscularly or intraperitoneally as follows: a 3/10-cc U-100 ultrafine insulin syringe with a 0.5-in.-long (ca. 1-cm-long) 29-gauge needle (catalog no. BD-309301; VWR) was used to inject 10 μl of the bacterial suspension into each fish. For intraperitoneal injection, an anesthetized fish was placed supine and supported by the moistened gauze-covered open jaws of a hemostat so that the head of the fish was positioned at the hinge of the hemostat. The needle was held parallel to the fish's spine and inserted cephalad into the midline of the abdomen just posterior to the pectoral fins. The needle was inserted up to the end of its bevel (1.5 mm), and 10 μl of bacterial suspension was injected.

Selected fish were injected with dye (0.1% bromophenol blue) and immediately euthanized for examination of the peritoneal cavity to ensure injection into the cavity and not into any internal organs. For intramuscular injection, an anesthetized fish was positioned prostrate, supported by the open jaws of a gauze-covered hemostat. The needle was inserted cephalad at a 45o angle relative to the spine into a position immediately anterior and lateral to the dorsal fin. The needle was inserted up to the end of its bevel, 10 μl of bacterial suspension was injected, and the needle was held in place for 5 s before it was withdrawn. All intramuscular and intraperitoneal experiments included injection of a full group of six fish with sterile THY+P. Infected fish were monitored as described above.

Statistical analyses.

For S. pyogenes and S. iniae, the 50% lethal dose (LD50) for infection of zebrafish by both the intramuscular and intraperitoneal routes of infection was determined by challenging zebrafish over a range of 101 to 106 CFU of each streptococcal species. For each determination, four separate experiments were performed in which six fish were infected with each concentration of streptococci. Survival data were analyzed by the method of Reed and Muench (53) for the calculation of the LD50. In other experiments, Kaplan-Meier product limit estimates of survival curves were used to compare infection by wild-type and various mutant streptococci, and differences were tested for significance by the log rank test (60).

Analysis of pathology.

Surface colonization was assessed by swabbing individual fish with a sterile cotton applicator that was then used to inoculate solid THY+P medium supplemented with the appropriate selective antibiotics. Following euthanasia, organs from selected infected and uninfected fish were removed by dissection with the aid of a stereomicroscope. Dissected organs were placed in a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube in 200 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) and homogenized with a microcentrifuge tube tissue grinder (Pellet Pestle, catalog no. K749520-0090; Fisher Scientific). Serial dilutions of homogenates were prepared in PBS, and numbers of CFU were determined by plating on medium containing the appropriate selective antibiotics. Examination of CFU was used to determine the relative bacterial load of each organ and was scored as follows: 0, no colonies; 1+, 1 to 50 colonies; 2+, 51 to 300 colonies, 3+, 301 to 700 colonies; 4+, >700 colonies.

Homogenates were also subjected to analysis by PCR with primers specific for S. iniae 16S rRNA sequences (74). Selected whole zebrafish were fixed following euthanasia by immersion in a commercial tissue fixative (Histochoice; Sigma; 10 ml per fish), with overnight incubation at room temperature. Fixed samples were routinely processed and then embedded in paraffin; 5-μm-thick longitudinal sections were prepared which were dewaxed and rehydrated by standard methods and then either stained with hematoxylin and eosin or processed further for immunohistochemistry. A rabbit antiserum against S. iniae was prepared by a commercial vendor (Covance, Denver, Pa.) by intradermal immunization with 250 μg (wet weight) of heat-killed whole S. iniae cells in complete Freund's adjuvant, followed by five booster subcutaneous injections of 125 μg each with incomplete Freund's adjuvant at days 28, 38, 76, 97, and 118 postimmunization.

Tissue sections were stained with the S. iniae antiserum at a dilution of 1:10 in PBS or with an antiserum to detect S. pyogenes (Lee Laboratories, Grayson, Ga.) at a dilution of 1:500. Following incubation for 2 h in a humidified atmosphere at room temperature, sections were washed extensively in PBS and allowed to react with goat anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated to either rhodamine red or fluorescein according to the recommendations of the manufacturer (Sigma). Samples were examined with an Olympus BX60 fluorescence microscope equipped with a digital camera and a motorized stage, and images captured from serial focal planes were subjected to deconvolution with MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging Corp.).

RESULTS

Establishing S. iniae infection in zebrafish.

In preliminary experiments, administration of a large dose of S. iniae (109 CFU) by the intraperitoneal route of infection resulted in the death of all infected zebrafish (n = 10) within 24 h. In contrast, when the same number of fish were injected with sterile medium alone, no fish died or demonstrated any symptom of discomfort, such as erratic swimming behavior or swimming abnormally near the surface of the water with an increased rate of respiration, even when examined over an extended period of time (up to 10 days). Death of the fish required viable bacteria, because fish injected with an equal number of heat-killed streptococci appeared symptom-free and remained healthy. Analysis by PCR to detect S. iniae-specific 16S rRNA demonstrated the presence of S. iniae in internal organs in zebrafish infected with viable streptococci, but no PCR products were obtained from fish injected with medium alone.

To facilitate recovery of the bacteria from infected fish, a spontaneous streptomycin-resistant S. iniae strain was selected (9117C), and this derivative had an LD50 by the intraperitoneal route of 103 CFU, with infected fish typically dying between 36 and 48 h postinfection. Internal organs were harvested from zebrafish showing visible symptoms of infection (see above) and analyzed for S. iniae by plating on streptomycin-containing medium. While no streptomycin-resistant colonies were obtained from fish injected with medium alone, colonies were recovered from the heart, brain, liver, and gallbladder of infected fish. A PCR analysis of selected colonies confirmed these as S. iniae. In addition, streptomycin-resistant colonies could be recovered from the surface of infected but not medium-injected fish.

When infected zebrafish were housed with uninfected fish, the uninfected fish did not demonstrate any sign of infection or show the presence of S. iniae in internal organs or on their surfaces. Adding high concentrations of S. iniae directly to aquarium water or an immersion of fish in a concentrated suspension of S. iniae also did not consistently result in infection of healthy fish, suggesting that healthy zebrafish are relatively refractory to S. iniae infection. In aquaculture, fish are most susceptible to S. iniae infection under conditions of stress, and these stressed fish often become wounded (32, 43, 46). When zebrafish were wounded by removal of a few scales followed by abrasion of the underlying dermis, these zebrafish readily became infected following brief exposure to a concentrated suspension of S. iniae (109 CFU/ml, 45 s) and typically died within 36 h, and large numbers of S. iniae organisms were recovered from both internal organs and the fish surface. Taken together, these results demonstrated that S. iniae successfully infects zebrafish and causes systemic disease over a period of days, which is similar to results reported for S. iniae infection of fish in aquaculture.

Quantitative analysis of infection.

Our findings that healthy fish are resistant to S. iniae infection while wounded fish are susceptible, along with the low LD50 of S. iniae following its introduction into a compartment with direct access to the vasculature (the peritoneal cavity), suggest that the key interactions in the host-pathogen relationship occur locally in tissue to limit the ability of S. iniae to invade across a tissue barrier. However, once the bacterium enters the vasculature, it has the capacity to rapidly overwhelm the normally very effective defenses of the bloodstream. In this regard, infection of fish by S. iniae is similar to invasive human streptococcal infection.

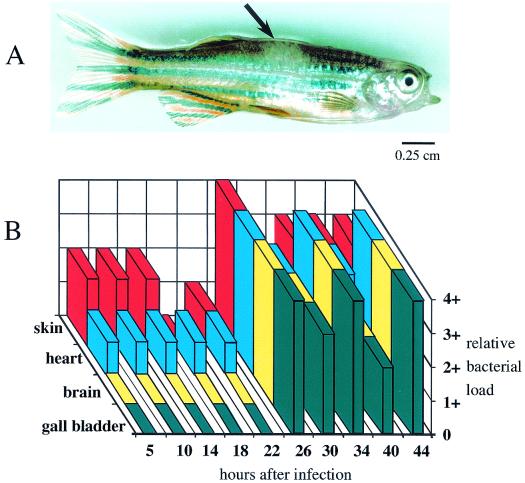

To exploit this similarity, the intramuscular route of infection was examined, which allowed quantitative monitoring of the ability of the bacterium to disseminate into and invade the vasculature and other organ systems. The intramuscular LD50 and time to death were similar to those by the intraperitoneal route (103 CFU and 36 to 48 h, respectively); however, the fish showed little sign of distress until just a few hours before death. Some infected fish (approximately 20%) showed a small (1 to 2 mm in diameter) well-demarcated hypopigmented lesion at the site of injection in the muscle (Fig. 1A). Examination of infection kinetics indicated that while small numbers of streptococci could be detected by 5 h postinfection in the vasculature, as detected by sampling muscle and blood from chambers of the heart, the numbers of organisms remained relatively constant until 26 h, when a dramatic increase was observed (Fig. 1B). Culturable streptococci in other organs (brain and gallbladder) remained below the limit of detection until a large increase occurred coincident with the increase observed in the vasculature (26 h, Fig. 1B) and remained at high levels over the subsequent course of infection (26 to 44 h, Fig. 1B). Colonization of the skin was observed at the earliest time point sampled (5 h, Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Infection of zebrafish by S. iniae. Appearance of a zebrafish 40 h post-intramuscular infection (A). The arrow indicates a hypopigmented lesion visible in the dorsal muscle that developed at the site of intramuscular injection of S. iniae. Distribution of S. iniae following intramuscular infection (B). The relative load of S. iniae in the indicated organs was determined at the times indicated and was scored as follows: 0, no colonies; 1+, 1 to 50 colonies; 2+, 51 to 300 colonies, 3+, 301 to 700 colonies; 4+, >700 colonies. A dose of 103 CFU was used for both A and B.

Histopathology of S. iniae intramuscular infection.

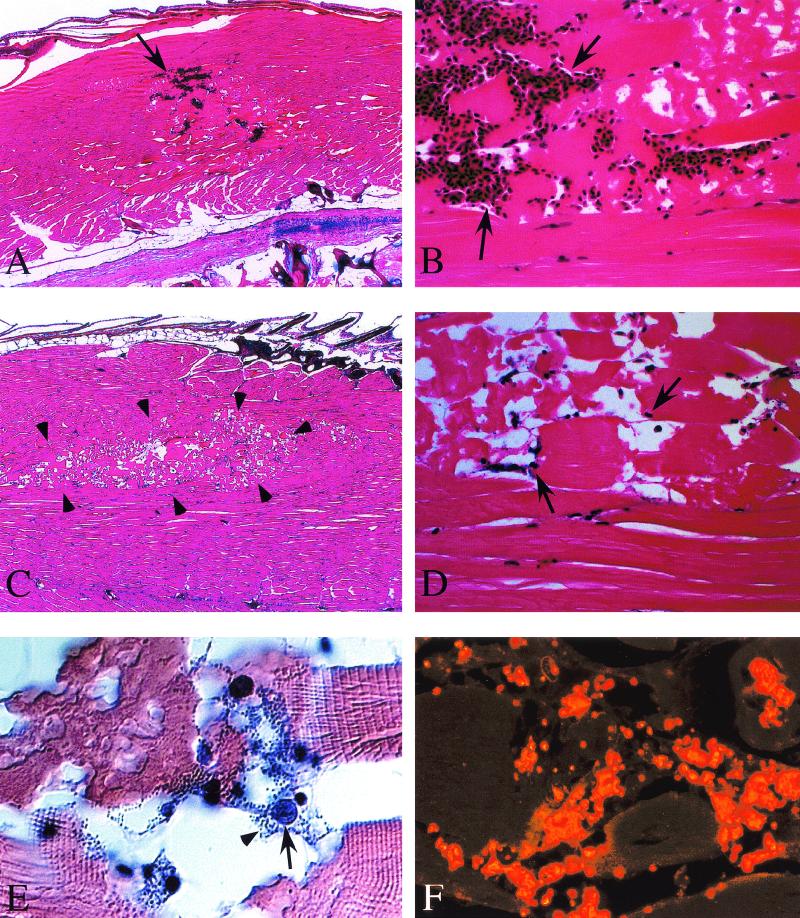

An advantage of zebrafish is that the entire animal can be fixed and sectioned in toto, allowing inspection of all organ systems in a single longitudinal section. Histopathological examination revealed that while there is some evidence of hemorrhage at the site of injection of medium alone in mock-infected zebrafish (note the arrows in Fig. 2A ), the muscle shows little evidence of damage other than hemorrhage at the site of injection (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the injection site of zebrafish showing visible symptoms of distress approximately 40 h postinfection with S. iniae shows a distinct well-demarcated zone of necrosis of the dorsal muscle that extends outward along tissue planes (outlined by the arrowheads in Fig. 2C). At higher magnification, tissue damage is shown to include extensive disruption of muscle architecture, with necrosis of myocytes, prominent intercellular edema, and a well-demarcated lesional border (Fig. 2D). Numerous exudative inflammatory cells were present in necrotic regions (arrows in Fig. 2D and 2E), and these cells were frequently associated with large aggregates of darkly stained coccus-shaped bacteria (arrowhead in Fig. 2E) which reacted with an antiserum against S. iniae (Fig. 2F). No staining with this antiserum was observed in fish injected with medium alone (not shown).

FIG.2.

Histopathological examination of S. iniae infection. Following intramuscular injection of 103 CFU, zebrafish were fixed in toto, and longitudinal sections were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or with an antiserum prepared against heat-killed S. iniae, as described in Materials and Methods. Dorsal muscle of a mock-infected zebrafish (A and B). Arrows indicate hemorrhage (A) and the presence of numerous erythrocytes (B) at the site of injection of sterile medium. Dorsal muscle at 40 h post-intramuscular infection by S. iniae (C, D, E, and F). Arrowheads outline a well-demarcated region of necrosis (C), and the arrows point to representatives of the numerous inflammatory cells present (D and E) that are associated with clusters of darkly stained coccus-shaped bacteria (arrowhead, E). These bacteria react with an antiserum raised against S. iniae (F). Liver of S. iniae-infected zebrafish (G). Arrowheads point to clusters of S. iniae in lumens of both large and small vessels. Thin arrows indicate morphology of representative normal-appearing hepatocytes, and thick arrows point to hepatocytes containing intracellular S. iniae. Brain of S. iniae-infected zebrafish (H). Arrowheads point to S. iniae visible in the lumen of a vessel invading the brain parenchyma. The arrow indicates S. iniae in an endothelial cell of a vessel in the meninges. Micrographs in panels E and F were obtained by differential interference contrast and fluorescence microscopy, respectively. Magnifications: A, ×40; B, ×400; C, ×40; D, ×400; E, ×1,000; F, ×1,000; G, ×1,200; H, ×1,200.

Examination of other tissues revealed evidence of extensive systemic infection. Numerous cocci were visible in the lumen of blood vessels systemically, including the gills (data not shown), both large and small vessels of the liver, and the brain (arrowheads, Fig. 2G and 2H). An interesting finding was the presence of numerous intracellular cocci in hepatocytes; the morphology of infected cells (thick arrows, Fig. 2G) differed from that of normal hepatocytes (thin arrows in Fig. 2G) and was characterized by fragmented nuclei, condensed cytoplasm, and a cellular membrane distended by the accumulation of large numbers of intracellular bacteria, which were also observed in scattered endothelial cells in the brain (arrow, Fig. 2H).

Infection by S. pyogenes.

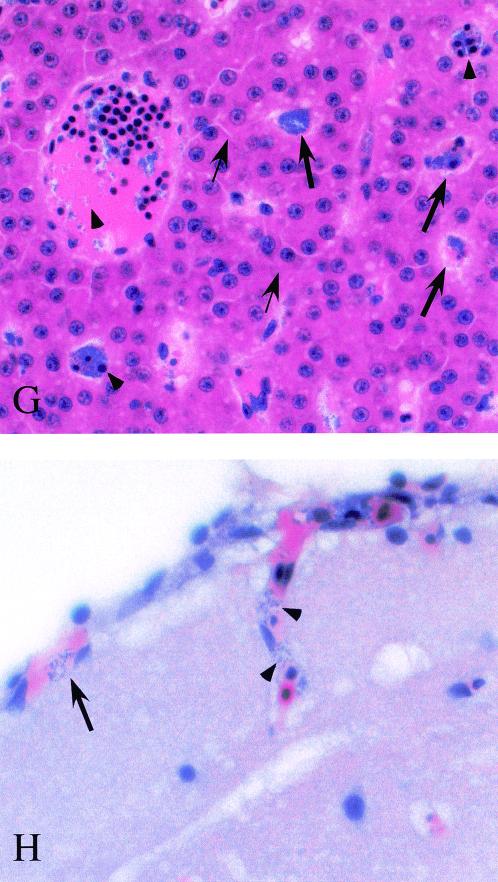

In humans, S. iniae causes disease in soft tissue that resembles S. pyogenes cellulitis. Thus, it was of interest to determine if S. pyogenes could cause disease in zebrafish. These studies revealed that, like S. iniae, S. pyogenes HSC5 produced a lethal infection by both the intramuscular and intraperitoneal routes, with a similar time to death (36 to 48 h). However, unlike S. iniae, the LD50 for S. pyogenes by the intraperitoneal route (2.5 × 102 CFU) was much lower than that for the intramuscular route (3 × 104 CFU). Also different was that all fish infected intramuscularly by S. pyogenes at a dose greater than the LD50 developed hypopigmented lesions in muscle by 24 h postinfection (Fig. 3A). These lesions were typically much larger than those caused by S. iniae, and they continued to expand in size until the death of the fish.

FIG. 3.

Infection of zebrafish by S. pyogenes. Appearance of a zebrafish 40 h post-intramuscular infection by S. pyogenes at a dose of 105 CFU (A). The arrow indicates a hypopigmented lesion visible in the dorsal muscle at the site of intramuscular injection. Histopathology of dorsal muscle (B, C, and D). Two representative regions of necrosis are outlined by the solid and open arrowheads, respectively (B). The arrow points to a large basophilic mass of streptococci dissecting along a tissue plane (C). The aggregates of streptococci react with an antiserum specific for S. pyogenes (D). The micrograph in panel D was obtained by fluorescence microscopy. Magnifications: B, ×40; C, ×520; D, ×400.

Similar for S. iniae, determination of CFU demonstrated that the surface of this fish became colonized at an early time point following infection by S. pyogenes. However, very few viable S. pyogenes organisms (<10 CFU) could be detected in internal organs and the vasculature, even in fish near death (data not shown). These observations were supported by histopathological examination and by immunostaining, which indicated little evidence of systemic infection (data not shown). In contrast, examination of the dorsal muscle revealed widespread damage, including multiple large regions of necrosis with spread of bacteria along tissue planes (representative regions are outlined by arrowheads in Fig. 3B). In contrast to infection by S. iniae, there was a striking absence of inflammatory cells in the S. pyogenes-infected tissue despite the prominent basophilic masses of bacteria that spread along tissue planes in the regions of necrotic muscle (note the arrow in Fig. 3C). These masses of bacteria reacted with an antiserum against S. pyogenes (Fig. 3D). Taken together, these data indicate that S. pyogenes is as efficient as S. iniae in infecting zebrafish. However, while S. iniae causes systemic disease early after intramuscular injection, S. pyogenes causes local muscle necrosis with direct extension.

Identification of streptococcal mutants with attenuated virulence.

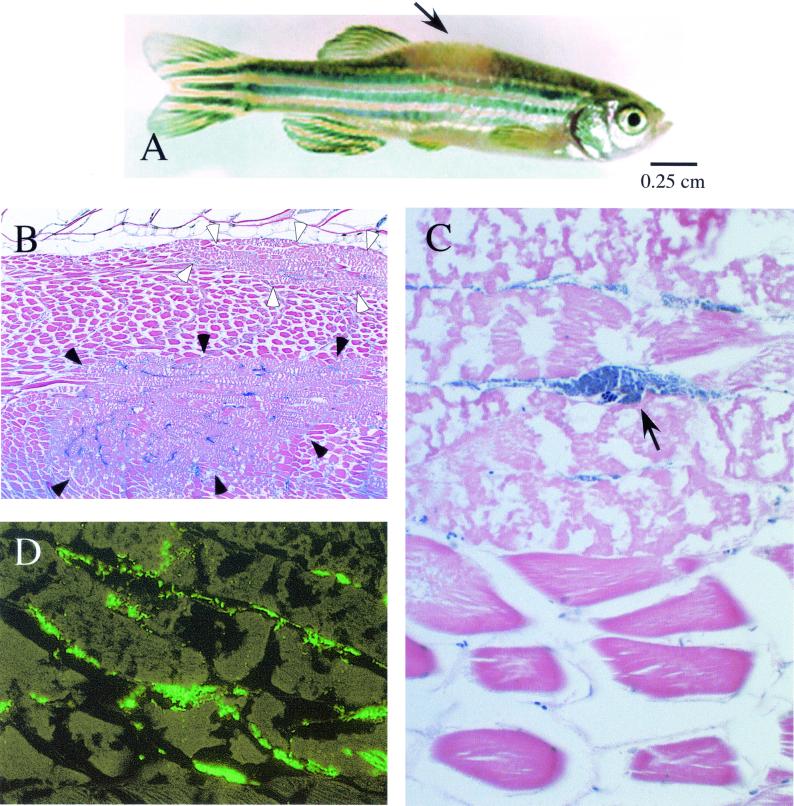

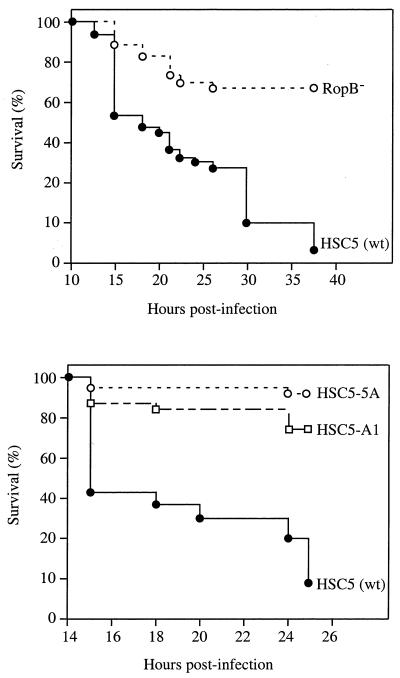

The utility of zebrafish as a model for understanding bacterial pathogenesis was further examined with S. pyogenes to take advantage of the genetic systems that have been developed for this organism (10), including the availability of multiple genome sequences (6). A first test was directed at determining whether a mutant of S. pyogenes HSC5 which was deficient in expression of a gene suggested to play a role in pathogenesis would show decreased virulence in zebrafish. The mutant chosen, HSC101, is defective for expression of ropB, a regulatory gene that is an essential activator of transcription of several genes, including the gene which encodes the secreted cysteine protease of S. pyogenes (12, 41). The cysteine protease has been implicated as a virulence factor in a murine model of soft tissue infection (36, 40). When compared in zebrafish by intramuscular challenge at a dose 10-fold higher than the LD50 of the wild-type strain, the RopB mutant was significantly less virulent than the wild type (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Mutants of S. pyogenes attenuated for zebrafish virulence. Kaplan-Meier curves comparing survival of zebrafish following intramuscular infection at a dose of 105 by wild-type and mutant S. pyogenes. The top of the figure compares survival following infection by the wild-type (wt) strain (HSC5, n = 37) to infection by a previously characterized mutant (RopB−, n = 37, P < 0.01). The bottom of the figure compares survival following infection by the wild-type strain (HSC5, n = 34) to infection by TnFuZ-generated mutants HSC5-A1 (n = 34, P < 0.01) and HSC5-5A (n = 34, P < 0.01). Each curve represents data pooled from four independent experiments.

A library of potential S. pyogenes mutants was then screened to identify novel virulence genes. Mutagenesis utilized a transposon modified to detect mutations in genes whose products are exported from the bacterial cell (25), thereby allowing the construction of a library of mutants defective for those molecules, which are the most likely to interact directly with the host. In the initial screen, 40 candidate mutants from eight independent pools were used to infect groups of six fish each at a dose 10-fold higher than the LD50 of the wild-type strain. Candidates showing reduced virulence were retested with larger groups of fish, and two mutants that were significantly less virulent than the wild type (HSC5-A1 and HSC5-5A, Fig. 4) were identified. Infection by both mutants differed from wild-type infection in that only a limited percentage of fish developed visible lesions, the lesions that did form were much smaller, and more inflammatory cells accumulated at the site of injection (data not shown).

Analysis of the loci altered in the mutants indicated that, as anticipated, each transposon had inserted into an open reading frame encoding a typical N-terminal signal sequence. Comparison to the published S. pyogenes genome sequence indicated that the gene inactivated in HSC5-A1 (genomic locus Spy1370) (23) had homology to a number of deacetylase enzymes and was most similar (30% identical, 50% similar) to a peptidoglycan N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase (PgdA) from Streptococcus pneumoniae (68). In HSC5-5A, the transposon had inserted into an open reading frame (genomic locus Spy1287) (23) with homology to a putative ABC-like transporter of S. pneumoniae (genetic locus Sp1715) (65). For both targeted genes, the downstream open reading frames were oriented in the opposite direction, suggesting that insertion of the transposon did not have a polar effect on a downstream gene, and neither of the targeted genes has previously been associated with virulence in this bacterium.

DISCUSSION

This study establishes a streptococcus-zebrafish model of bacterial pathogenesis combining a vertebrate host and a pathogen that are both amenable to genetic analysis. Other advantages include that zebrafish are easily maintained in large numbers and at low cost, that the streptococcal species used are readily cultured in vitro, and that they caused diseases with symptoms and pathology that were easily monitored. Also, the two streptococcal species both caused acute disease; however, each had a distinct pathogenesis. Finally, the diseases caused in zebrafish resembled both those caused by streptococci in farmed fish populations and those of several different streptococcal infections in humans. Thus, this model will be valuable for further studies on bacterial pathogenesis.

The fact that zebrafish have adaptive and innate cellular immune defenses that are not unlike those of the mammalian species most often used to model infectious diseases of humans (66) makes them highly useful as a model host organism. Fish have immunoglobulins, antigen-processing cells, T cells, and B cells (30, 72, 73) as well as complement, and phagocytic cells and leukocytes capable of producing reactive species of oxygen and nitrogen (33). Zebrafish genome projects have identified orthologs of mammalian genes, including those encoding cytokines and major histocompatibility complex molecules, that are known to be involved in the regulation of immune responses (4, 75). In fact, vaccination of fish against certain pathogens has been of value in aquaculture, and vaccines against S. iniae are under development (19). Thus, it is likely that the underlying principles of host-pathogen relationships in fish will be very similar to those in humans. Further support for this comes from the fact that S. iniae can infect humans and causes disease in soft tissue that resembles that caused by S. pyogenes (69, 70).

Immunoglobulin responses play important roles in protection of humans from streptococcal disease. However, the development of vaccines has been complicated by the abilities of various streptococcal species to vary the structures of their protective antigens. A recent report suggests that antigenic variation may also occur among strains of S. iniae (2). However, in the present study, the time to death occurred over a period that was likely too short to engage the adaptive arm of the immune system. This suggests that in lethal and sublethal infections, the pathogens interacted primarily with innate immune effectors at the site of entry and that the outcome of this interaction had a major influence on the progression and outcome of disease. Thus, this model will be useful for analysis of the zebrafish innate immunity and the interaction of streptococci and innate immune effectors in tissue. Studies directed at developing a protective immunity will be useful for probing the zebrafish adaptive immune system and will aid streptococcal vaccine efforts.

For S. iniae, clusters of streptococci in muscle were associated with exudative inflammatory cells that were likely recruited by the innate immune response. This suggests that, as for many species of pathogenic streptococci, an important virulence property of S. iniae is the ability to avoid recognition by phagocytic inflammatory cells. Consistent with this is a recent study which reports that a characteristic which distinguishes lineages of S. iniae virulent for humans from lineages not associated with human disease is the ability to avoid uptake by human peripheral blood leukocytes (24). Following growth in muscle, dissemination of streptococci followed rapidly and was associated with the presence of intracellular streptococci in the liver and endothelial cells of the vessels of the brain. In the latter case, the bacteria may be in the process of invading the subarachnoid space, which is the pathway of entry thought to be important for the pathogenesis of streptococcal meningitis in humans (59).

The significance of intracellular streptococci in hepatocytes is unclear, as is the ability of S. iniae to invade cultured mammalian cells in vitro (24). However, the liver is the site of replication of many bacterial pathogens for which multiplication in an intracellular compartment is an integral element of pathogenesis. For example, Listeria monocytogenes invades hepatocytes following uptake by liver macrophages, and intracellular multiplication induces the hepatocytes to undergo apoptosis, resulting in the release of interleukin-1α and an innate immune response leading to microabscess formation (28, 29, 56). However, the formation of abscesses was not observed in livers of S. iniae-infected zebrafish.

The pathogenesis of S. pyogenes infection was distinctly different from that of S. iniae and was characterized by an absence of intracellular bacteria and systemic spread at a time when the dorsal muscle was extensively damaged. In addition, S. pyogenes grew in large, densely packed masses of bacteria that disseminated along tissue planes, with a marked absence of inflammatory cells in the damaged tissue. This pathology is strikingly similar to that reported for an experimental, fatal intramuscular infection with S. pyogenes in baboons (64). These data suggest that important virulence properties of S. pyogenes are those which promote growth of the bacteria in biofilm-like masses and those that inhibit the recruitment of and/or kill inflammatory cells.

In general, streptococci secrete multiple biologically active molecules into their environments, and for S. pyogenes specifically, numerous secreted molecules have activities that affect the viability and function of phagocytic cells (13, 39). Intoxication from molecules released from the large bacterial load in necrotic tissue may be the factor that leads to the eventual death of infected zebrafish. However, it is also possible that the acute death response is precipitated by an extensive breakdown of tissue barriers, resulting in the abrupt release of large numbers of streptococci into the bloodstream and a subsequent lethal shock. Evidence that this pathway may be active is provided by the observation that the LD50 for intraperitoneal injection where the bacteria have an unencumbered path to the vasculature was approximately 100-fold lower than for intramuscular injection. Results from preliminary data of a murine model of cutaneous infection with the transposon mutant HSC5-A1 show a marked decrease in virulence compared to that of the wild-type strain, further validating the reliability of the zebrafish model.

It is not understood why some streptococcal species cause systemic infection and others cause local infection in tissue. In some cases, strains within the same species differ in whether they cause systemic or local infection. Thus, identification and comparison of the genes that promote virulence of S. iniae and S. pyogenes in zebrafish may be useful for understanding the molecular basis of this phenomenon. In the present study, it was found that at least one gene that is associated with toxin expression in S. pyogenes contributes to virulence in zebrafish. In a preliminary screen for new mutants, two additional virulence genes were identified, demonstrating that it will be feasible to conduct large-scale screens in zebrafish to continue this comparison.

The low cost and small size of zebrafish allow the testing of individual isolates from a large pool of potential mutants, so it is not necessary to use any of the negative selection protocols, such as signature-tagged mutagenesis, that have been developed to minimize the number of animals required for identification of avirulent mutants. Of the genes identified in the two mutants attenuated for zebrafish virulence, one was most similar to pdgA of S. pneumoniae, where it was identified as a gene required for the ability of the peptidoglycan of the gram-positive cell wall to resist digestion by lysozyme (68). This may suggest that host lysozyme may be a component of the host defense response in the zebrafish muscle. The second gene was most similar to a putative ABC transporter in S. pneumoniae that was recently identified in a large-scale signature-tagged mutagenesis screen for virulence genes in a murine model of systemic infection (38). The fact that the screens in this study have identified genes that support virulence in both zebrafish and mice suggests that zebrafish will be a useful model for bacterial pathogenesis.

In addition to differences, analysis of similarities between S. iniae and S. pyogenes infections will also be informative. One interesting similarity is that only the skin of infected fish that developed disease became colonized by streptococci, while the skin of uninfected fish and fish infected at sublethal doses remained uncolonized. Fish respond to stress by increasing levels of cortisol in serum (43, 57), which can induce a profound immunosuppression (22, 43, 46, 67). A serious infection resulting in damage to tissue would likely induce this response, which may depress a defense critical for controlling bacterial colonization on the skin. Fish in aquaculture become most susceptible to S. iniae infection under conditions of stress (46), including overcrowding, improper temperature, overfeeding, and poor water quality. In preliminary experiments, infection by exposure to streptococci in water was possible when the zebrafish were housed for short periods of time under conditions which mimicked aspects of a stressful aquaculture environment. Refinement of these conditions may make it possible to conduct large-scale screens for zebrafish genes that are involved in host-pathogen interactions.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Joyce de Azavedo for providing strains of S. iniae. We thank Steve Johnson for teaching us about zebrafish and Jeremy Ortiz for technical assistance.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI38273, AI46433, and AR45254.

Editor: E. I. Tuomanen

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachrach, G., A. Zlotkin, A. Hurvitz, D. L. Evans, and A. Eldar. 2001. Recovery of Streptococcus iniae from diseased fish previously vaccinated with a streptococcus vaccine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3756-3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker, C. J., and M. S. Edwards. 1995. Group B streptococcal infections, p. 980-1054. In J. S. Remington and J. O. Klein (ed.), Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant, 4th ed. W. B. Saunders, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 4.Barbazuk, W. B., I. Korf, C. Kadavi, J. Heyen, S. Tate, E. Wun, J. A. Bedell, J. D. McPherson, and S. L. Johnson. 2000. The syntenic relationship of the zebrafish and human genomes. Genome Res. 10:1351-1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baya, A. M., B. Lupiani, F. M. Hetrick, B. S. Roberson, R. Lukakovic, E. May, and C. Poukish. 1990. Association of Streptococcus spp. with fish mortalities in the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. J. Fish Dis. 41:251-253. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benson, D. A., I. Karsch-Mizrachi, D. J. Lipman, J. Ostell, B. A. Rapp, and D. L. Wheeler. 2000. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:15-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berridge, B. R., J. D. Fuller, J. de Azavedo, D. E. Low, H. Bercovier, and P. F. Frelier. 1998. Development of specific nested oligonucleotide PCR primers for the Streptococcus iniae 16S-23S ribosomal DNA intergenic spacer. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2778-2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bisno, A. L., and D. L. Stevens. 1996. Streptococcal infections of skin and soft tissues. N. Engl. J. Med. 334:240-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bromage, E. S., A. Thomas, and L. Owens. 1999. Streptococcus iniae, a bacterial infection in barramundi Lates calcarifer. Dis. Aquat. Org. 36:177-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caparon, M. G. 2000. Genetics of group A streptococci, p. 53-65. In V. A. Fischetti, R. P. Novick, J. J. Ferretti, D. A. Portnoy, and J. I. Rood (ed.), Gram-positive pathogens. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 11.Caparon, M. G., and J. R. Scott. 1991. Genetic manipulation of the pathogenic streptococci. Methods Enzymol. 204:556-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaussee, M. S., D. Ajdic, and J. J. Ferretti. 1999. The rgg gene of Streptococcus pyogenes NZ131 positively influences extracellular SPE B production. Infect. Immun. 67:1715-1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunningham, M. W. 2000. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:470-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darby, C., C. L. Cosma, J. H. Thomas, and C. Manoil. 1999. Lethal paralysis of Caenorhabditis elegans by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:15202-15207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dushay, M. S., and E. D. Eldon. 1998. Drosophila immune responses as models for human immunity. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 62:10-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eldar, A., Y. Bejerano, and H. Bercovier. 1994. Streptococcus shiloi and Streptococcus difficile: two new streptococcal species causing a meningoencephalitis in fish. Curr. Microbiol. 28:139-143. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eldar, A., Y. Bejerano, A. Livoff, A. Horovitz, and H. Bercovier. 1995. Experimental streptococcal meningo-encephalitis in cultured fish. Vet. Microbiol. 43:33-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eldar, A., P. F. Frelier, L. Asanta, P. W. Varner, S. Lawhorn, and H. Bercouvier. 1995. Streptococcus shiloi, the name for an agent causing septicemic infection in fish, is a junior synonym of Streptococcus iniae. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:840-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eldar, A., A. Horovitcz, and H. Bercovier. 1997. Development and efficacy of a vaccine against Streptococcus iniae infection in farmed rainbow trout. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 56:175-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eldar, A., S. Lawhorn, P. F. Frelier, L. Assenta, B. R. Simpson, P. W. Varner, and H. Bercouvier. 1997. Restriction fragment length polymorphisms of 16S rDNA and of whole rRNA genes (ribotyping) of Streptococcus iniae strains from the United States and Israel. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 151:155-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eldar, A., S. Perl, P. F. Frelier, and H. Bercovier. 1999. Red drum Sciaenops ocellatus mortalities associated with Streptococcus iniae infection. Dis. Aquat. Org. 36:121-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellsaesser, C. F., and L. W. Clem. 1987. Cortisol-induced hematologic and immunologic changes in channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 87:405-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferretti, J. J., W. M. McShan, D. Ajdic, D. J. Savic, G. Savic, K. Lyon, C. Primeaux, S. Sezate, A. N. Suvorov, S. Kenton, H. S. Lai, S. P. Lin, Y. Qian, H. G. Jia, F. Z. Najar, Q. Ren, H. Zhu, L. Song, J. White, X. Yuan, S. W. Clifton, B. A. Roe, and R. McLaughlin. 2001. Complete genome sequence of an M1 strain of Streptococcus pyogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4658-4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuller, J. D., D. J. Bast, V. Nizet, D. E. Low, and J. C. de Azavedo. 2001. Streptococcus iniae virulence is associated with a distinct genetic profile. Infect. Immun. 69:1994-2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibson, C. M., and M. G. Caparon. 2002. Alkaline phosphatase reporter transposon for analysis of protein secretion in gram-positive microorganisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:928-932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Gillespie, S. H., and I. Balakrishnan. 2000. Pathogenesis of pneumococcal infection. J. Med. Microbiol. 49:1057-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gosink, K., and E. Tuomanen. 2000. Streptococcus pneumoniae: invasion and inflammation, p. 214-224. In V. A. Fischetti, R. P. Novick, J. J. Ferretti, D. A. Portnoy, and J. I. Rood (ed.), Gram-positive pathogens. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 28.Gregory, S. H., and C.-C. Liu. 2000. CD8+ T-cell-mediated response to Listeria monocytogenes taken up in the liver and replicating within hepatocytes. Immunol. Rev. 174:112-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gregory, S. H., A. J. Sagnimeni, and E. J. Wing. 1992. Effector function of hepatocytes and Kupffer cells in the resolution of systemic bacterial infections. J. Leukoc. Biol. 51:421-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haire, R. N., J. P. Rast, R. T. Litman, and G. W. Litman. 2000. Characterization of three isotypes of immunoglobulin light chains and T-cell antigen receptor alpha in zebrafish. Immunogenetics 51:915-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanski, E., P. A. Horowitz, and M. G. Caparon. 1992. Expression of protein F, the fibronectin-binding protein of Streptococcus pyogenes JRS4, in heterologous streptococcal and enterococcal strains promotes their adherence to respiratory epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 60:5119-5125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris, J., and D. J. Bird. 2000. Modulation of the fish immune system by hormones. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 77:163-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herbomel, P., B. Thisse, and C. Thisse. 1999. Ontogeny and behaviour of early macrophages in the zebrafish embryo. Development 126:3735-3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaige, N., T. Miyazaki, and S. Kubota. 1984. The pathogen and histopathology of vertebral deforminty in cultured yellowtail Seriola quinqueradiata. Fish Pathol. 19:173-180. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kopp, E. B., and R. Medzhitov. 1999. The Toll-receptor family and control of innate immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 11:13-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuo, C.- F., J.- J. Wu, K.- Y. Lin, P.- J. Tsai, S.- C. Lee, Y.- T. Jin, H.- Y. Lei, and Y.- S. Lin. 1998. Role of streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin B in the mouse model of group A streptococcal infection. Infect. Immun. 66:3931-3935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kusuda, R. 1992. Bacterial fish diseases in mariculture in Japan with special emphasis on streptococcosis. Isr. J. Aquacult. 44:140. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lau, G. W., S. Haataja, M. Lonetto, S. E. Kensit, A. Marra, A. P. Bryant, D. McDevitt, D. A. Morrison, and D. W. Holden. 2001. A functional genomic analysis of type 3 Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 40:555-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lei, B., S. Mackie, S. Lukomski, and J. M. Musser. 2000. Identification and immunogenicity of group A streptococcus culture supernatant proteins. Infect. Immun. 68:6807-6818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lukomski, S., S. Sreevatsan, C. Amberg, W. Reichardt, M. Woischnik, A. Podbielski, and J. M. Musser. 1997. Inactivation of Streptococcus pyogenes extracellular cysteine protease significantly decreases mouse lethality of serotype M3 and M49 strains. J. Clin. Investig. 99:2574-2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lyon, W. R., C. M. Gibson, and M. G. Caparon. 1998. A role for trigger factor and an Rgg-like regulator in the transcription, secretion, and processing of the cysteine proteinase of Streptococcus pyogenes. EMBO J. 17:66263-66275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mahajan-Miklos, S., M.-W. Tan, L. G. Rahme, and F. M. Ausubel. 1999. Molecular mechanisms of bacterial virulence elucidated with a Pseudomonas aeruginosa-Caenorhabditis elegans pathogenesis model. Cell 96:47-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ortuno, J., M. A. Esteban, and J. Meseguer. 2001. Effects of short-term crowding stress on the gilthead seabream (Spartus aurata L.) innate immune response. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 11:187-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearce, B. J., Y. B. Yin, and H. R. Masure. 1993. Genetic identification of exported proteins in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 9:1037-1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perera, R. P., S. K. Johnson, M. D. Collins, and D. H. Lewis. 1994. Streptococcus iniae associated with mortality of Tilapia nilotica and T. aurea hybrids. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 6:335-340. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pickering, A. D., and J. Duston. 1983. Administration of cortisol to brown trout, Salmo trutta L., and its effects on the susceptibility to Saprolegnia infection and furunculosis. J. Fish Biol. 23:163-175. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pier, G., and S. Madin. 1976. Streptococcus iniae sp. nov., a beta-hemolytic streptococcus isolated from an Amazon freshwater dolphin, Inia geoffrensis. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 26:545-553. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pier, G., S. Madin, and S. Al-Nakeeb. 1978. Isolation and characterization of a second isolate of Streptococcus iniae. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 28:311-314. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Postlethwait, J. H., Y. L. Yan, M. A. Gates, S. Horne, A. Amores, A. Brownlie, A. Donovan, E. S. Egan, A. Force, Z. Gong, C. Goutel, A. Fritz, R. Kelsh, E. Knapik, E. Liao, B. Paw, D. Ransom, A. Singer, M. Thomson, T. S. Abduljabbar, P. Yelick, D. Beier, J. S. Joly, D. Larhammar, F. Rosa, et al. 1998. Vertebrate genome evolution and the zebrafish gene map. Nat. Genet. 18:345-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qureshi, S. T., P. Gros, and D. Malo. 1999. Host resistance to infection: genetic control of lipopolysaccharide responsiveness by TOLL-like receptor genes. Trends Genet. 15:291-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rahme, L. G., E. J. Stevens, S. F. Wolfort, J. Shao, R. G. Tompkins, and F. M. Ausubel. 1995. Common virulence factors for bacterial pathogenicity in plants and animals. Science 30:1899-1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rahme, L. G., M. W. Tan, L. Le, S. M. Wong, R. G. Tompkins, S. B. Calderwood, and F. M. Ausubel. 1997. Use of model plant hosts to identify Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:13245-13250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reed, L. J., and H. Muench. 1938. A simple method of estimation of fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 27:493-497. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ring, A., J. Weiser, and E. Tuomanen. 1998. Pneumococcal trafficking across the blood-brain barrier. J. Clin. Investig. 102:1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rock, F. L., G. Hardiman, J. C. Timans, R. A. Kastelein, and J. F. Bazan. 1998. A family of human receptors structurally related to Drosophila Toll. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:588-593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rogers, H. W., M. P. Callery, B. Deck, and E. R. Unanue. 1996. Listeria monocytogenes induces apoptosis of infected hepatocytes. J. Immunol. 156:679-684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rotllant, J., P. H. Balm, J. Perez-Sanchez, S. E. Wendelaar-Bonga, and L. Tort. 2001. Pituitary and interrenal function in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata L. Teleostei) after handling and confinement stress. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 121:333-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schuchat, A. 1998. Epidemiology of group B streptococcal disease in the United States: shifting paradigms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:497-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spellerberg, B. 2000. Pathogenesis of neonatal Streptococcus agalactiae infections. Microbes Infect. 2:1733-1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.SPSS Inc. 1999. SPSS advanced models, version 10.0. SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill.

- 61.Stemple, D. L., and W. Driever. 1996. Zebrafish: tools for investigating cellular differentiation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 8:858-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stevens, D. L. 1992. Invasive group A streptococcus infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 14:2-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tan, M. W., and F. M. Ausubel. 2000. Caenorhabditis elegans: a model genetic host to study Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:29-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taylor, F. B. J., A. E. Bryant, K. E. Blick, E. Hack, P. M. Jansen, S. D. Kosanke, and D. L. Stevens. 1999. Staging of the baboon response to group A streptococci administered intramuscularly: a descriptive study of the clinical symptoms and clinical chemical response patterns. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:167-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tettelin, H., K. E. Nelson, I. T. Paulsen, J. A. Eisen, T. D. Read, S. Peterson, J. Heidelberg, R. T. DeBoy, D. H. Haft, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, M. Gwinn, J. F. Kolonay, W. C. Nelson, J. D. Peterson, L. A. Umayam, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, M. R. Lewis, D. Radune, E. Holtzapple, H. Khouri, A. M. Wolf, T. R. Utterback, C. L. Hansen, L. A. McDonald, T. V. Feldblyum, S. Angiuoli, T. Dickinson, E. K. Hickey, I. E. Holt, B. J. Loftus, F. Yang, H. O. Smith, J. C. Venter, B. A. Dougherty, D. A. Morrison, S. K. Hollingshead, and C. M. Fraser. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a virulent isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Science 293:498-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trede, N. S., A. G. Zapata, and L. I. Zon.2001. Fishing for lymphoid genes. Trends Immunol. 22:302-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tripp, R. A., A. G. Maule, C. B. Schreck, and S. L. Kaattari. 1987. Cortisol mediated suppression of salmonid lymphocyte responses in vitro. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 11:565-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vollmer, W., and A. Tomasz. 2000. The pgdA gene encodes for a peptidoglycan N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Biol. Chem. 275:20496-20501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weinstein, M. R., M. Litt, D. A. Kertesz, P. Wyper, D. Rose, M. Coulter, A. McGeer, R. Facklam, C. Ostach, B. M. Willey, A. Borczyk, and D. E. Low. 1997. Invasive infections due to a fish pathogen, Streptococcus iniae. N. Engl. J. Med. 337:589-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weinstein, M. R., D. E. Low, A. McGeer, B. Willey, D. Rose, M. Coulter, P. Wyper, A. Borczyk, and M. Lovgren. 1996. Invasive infection due to Streptococcus iniae: a new or previously unrecognized disease. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 22:129-132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Westerfield, M. 1995. The zebrafish book: guide for the laboratory use of zebrafish (Danio rerio), 3rd ed. University of Oregon Press, Eugene.

- 72.Willett, C. E., A. Cortes, A. Zuasti, and A. G. Zapata. 1999. Early hematopoiesis and developing organs in the zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 214:323-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Willett, C. E., A. G. Zapata, N. Hopkins, and L. A. Steiner. 1997. Expression of zebrafish rag genes during early development identifies the thymus. Dev. Biol. 182:331-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zlotkin, A., H. Hershko, and A. Eldar. 1998. Possible transmission of Streptococcus iniae from wild fish to cultured marine fish. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4065-4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zon, L. I. 1999. Zebrafish: a new model for human disease. Genome Res. 9:99-100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]