Abstract

Analysis of the genome sequence of a serotype M1 group A Streptococcus (GAS) strain identified a gene encoding a previously undescribed putative cell surface protein. The gene was cloned from a serotype M1 strain, and the recombinant protein was overexpressed in Escherichia coli and purified to homogeneity. The purified protein was associated with heme in a 1:1 stoichiometry. This streptococcal heme-associated protein, designated Shp, was produced in vitro by GAS, located on the bacterial cell surface, and accessible to specific antibody raised against the purified recombinant protein. Mice inoculated subcutaneously with GAS and humans with invasive infections and pharyngitis caused by GAS seroconverted to Shp, indicating that Shp was produced in vivo. The blood of mice actively immunized with Shp had significantly higher bactericidal activity than the blood of unimmunized mice. The shp gene was cotranscribed with eight contiguous genes, including homologues of an ABC transporter involved in iron uptake in gram-negative bacteria. Our results indicate that Shp is a novel cell surface heme-associated protein.

Group A Streptococcus (GAS) is a gram-positive human pathogen that causes a variety of diseases, such as pharyngitis, cellulitis, bacteremia, streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, necrotizing fasciitis, and postinfection sequelae, including acute rheumatic fever, rheumatic heart disease, and glomerulonephritis (26). GAS pharyngitis results in substantial morbidity and economic loss globally, and severe invasive infections are associated with high morbidity and mortality rates.

Extracellular proteins that mediate pathogen adhesion, evasion of host immune responses, tissue destruction, and nutrient uptake play vital roles in the life cycle of GAS (3, 18). GAS extracellular proteins can be assigned to two broad categories, i.e., actively secreted proteins found free in the culture supernatant and proteins that are located predominantly on the bacterial cell surface. Most actively secreted proteins have characteristic gram-positive secretion signal sequences located at the amino terminus. Cell surface proteins are attached to the cell surface in several ways. For example, lipoproteins are anchored to the bacterial cell membrane by a lipid moiety located at the amino terminus (33). In addition, many gram-positive bacterial cell surface proteins, including several made by GAS, are covalently cross-linked to the cell wall through a conserved pentapeptide sequence (Leu-Pro-X-Thr-Gly [LPXTG]) that is followed by a stretch of hydrophobic residues and a short charged tail located at the carboxy terminus (9).

Recently we analyzed the supernatant proteome of GAS in an initial effort to identify novel secreted proteins for pathogenesis and therapeutics research (17). However, important secreted proteins may not have been identified by our proteome analysis because of limited in vitro expression, technical difficulties associated with proteomics, or the fact that we analyzed culture supernatant proteins only. Therefore, bioinformatic methods were used to analyze a serotype M1 GAS genome (8) and identify genes encoding putative uncharacterized extracellular proteins. We identified a hypothetical protein that, like LPXTG-containing cell surface proteins, has a presumed secretion signal sequence located at the amino terminus and a putative transmembrane domain and short charged tail at the carboxy terminus but lacks an LPXTG motif. We report here that this protein (designated Shp) associates with heme, is located on the bacterial cell surface where it is accessible to specific antibody, and is expressed in vivo in human infections. The structural gene is cotranscribed with genes encoding homologues of an ABC transporter involved in iron uptake in gram-negative bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth.

GAS strains MGAS5005 (serotype M1) and MGAS315 (serotype M3) have been described previously and characterized extensively (21-23, 25). GAS strains were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 0.2% yeast extract (THY). Iron-restricted conditions were achieved by treating THY with the chelating resin Chelex 100 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) and supplementing it with 0.4 mM each CaCl2, MgCl2, MnCl2, and ZnCl2 (DTHY) (6). Tryptose agar with 5% sheep blood (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.) or brain heart infusion agar (Difco Laboratories) was used as solid medium. Escherichia coli strains NovaBlue and BL21(DE3) (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) were used for gene cloning and protein expression, respectively.

Gene cloning.

A portion of the gene encoding amino acids 30 to 258 of Shp was cloned from strain MGAS5005 with primers 5′-ACCATGGATAAAGGTCAAATTTATGGATG-3′ and 5′-CGAATTCTTAGTCTTTTTTAGACCGAAACTTATC-3′. The protein made from this cloned fragment lacks the presumed secretion signal sequence (amino acid 1 to 29) and the transmembrane domain and charged tail (amino acids 259 to 291) located at the carboxy terminus. The underlined bases were added to introduce an NcoI restriction site-initiation codon and an EcoRI site-stop codon, respectively. The PCR product was digested with NcoI and EcoRI and ligated into pET-21d (Novagen) to yield recombinant plasmid pSHP. The cloned gene fragment was sequenced to rule out spurious mutations.

Analysis of gene transcription.

MGAS5005 cells grown to mid-exponential phase were harvested by centrifugation and processed with the FastRNA Kit BLUE (Q Biogene, Carlsbad, Calif.), using a FastPrep FP120 instrument (Bio 101, La Jolla, Calif.), as previously described (31). The lysate was incubated for 15 min at 65°C, centrifuged to remove cell debris, and treated with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). The RNA was treated with 100 U of DNase I (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) for 2 h at 37°C to remove contaminating DNA. Purification of the RNA and removal of DNase I were achieved by repeating the RNeasy Mini protocol. RNA quality was examined spectrophotometrically with a 2100 Bioanalyzer and RNA 6000 LabChip Kit (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, Calif.). The absence of contaminating DNA was confirmed by PCR. RNA was reverse transcribed into DNA with SuperScript II (Gibco, Rockville, Md.) as described in the manufacturer's instructions. PCR amplifications were performed with the cDNA as the template and the primers listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primer pairs used in RT-PCR analysis of the gene cluster containing shp

| Primera | Sequence (5′→3′) | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| shpF | GATAAAGGTCAAATTTATGGATG | 755 |

| shpR | CCAAACCCATACAGCAAACC | |

| shpF | GATAAAGGTCAAATTTATGGATG | 1,271 |

| 1795R | GGCTTTTTCTTCCCCTTACG | |

| 1795F | ATTGTAGCCACTTCGGTTGC | 1,329 |

| 1794R | GCTGAGGTGAAAAAGCTGGT | |

| 1794F | GGCAATTGTCAAGGGACTGT | 1,538 |

| 1793R | AAGTCGCCCATCTTTCAGTC | |

| 1793F | CCATCAAGTGGTCGAAGGTT | 1,751 |

| 1791R | AGACTGGCGTTTCAAGAGGA | |

| 1791F | TGGGAATTGGTTTGTCAGGT | 5,115 |

| 1787R | CCAAAAGACTAGCGGCAATC |

Numbers correspond to SPy gene designations in GAS strain SF370. F, forward; R, reverse.

TaqMan assays were performed as described previously (2), with a probe and primers specific for shp. Strain MGAS5005 was cultured in THY at 37°C with 5% CO2 and harvested at optical densities at 600 nm (OD600s) of 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8. The level of transcription of the shp gene was compared with that of gyrA, a gene transcribed constitutively at the same level throughout the GAS growth cycle (2).

Purification of recombinant Shp.

Recombinant Shp was purified from E. coli BL21(DE3) containing pSHP. The bacteria were grown overnight at 37°C in 6 liters of Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with 100 mg of ampicillin per liter. The bacteria were harvested by centrifugation, suspended in 70 ml of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), and sonicated on ice for 15 min. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 15 min, the supernatant was loaded on a DEAE-Sepharose column (2.5 by 10 cm), and the protein was eluted with a 100-ml linear gradient of 0 to 0.4 M NaCl. Shp was identified by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and peak fractions were pooled. The protein was precipitated with 70% (NH4)2SO4, recovered by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 15 min, suspended in a minimal volume of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), and loaded onto a phenyl-Sepharose column (1.5 by 10 cm) equilibrated with 1.5 M (NH4)2SO4. The column was washed with 50 ml of 1.5 M (NH4)2SO4 and eluted with a 100-ml linear gradient of 1.5 M to 0.5 M (NH4)2SO4, and fractions containing Shp were pooled and precipitated as described above. The protein was suspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3) and dialyzed for 20 h against two changes of 3.5 liters of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8). The dialyzed protein was loaded onto a SP-Sepharose column (2.5 by 10 cm) and eluted with a 100-ml gradient of 0 to 200 mM NaCl in Tris-HCl (pH 6.8). Protein purified with this protocol was free of contaminating proteins as assessed by SDS-PAGE with Coomassie blue staining. Protein concentrations were measured with the modified Lowry protein assay kit purchased from Pierce (20) with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard.

Determination of heme content.

A pyridine hemochrome assay (10) was used to assess the existence and content of heme associated with purified Shp. Purified recombinant Shp in 750 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) was mixed with 170 μl of pyridine, 75 μl of 1 N NaOH, and 2 mg of sodium hydrosulfite, and the optical spectrum was recorded immediately with an Ultraspec 4000 UV-visible spectrophotometer (Pharmacia). Heme content was determined by measuring the absorbance at 418 nm with the equation ɛ418 = 191.5 mM−1 cm−1 (10). Purified Mycobacterium tuberculosis catalase-peroxidase (KatG), a known heme-containing protein, was used as a positive control (16).

Measurement of iron by ICP-MS.

Shp and a control protein (purified recombinant putative dipeptide-binding lipoprotein encoded by spy2000), each at 50 μM in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), were diluted 30-fold with 2% nitric acid and analyzed with an HP4500 inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) instrument equipped with a CETAC ASX-500 autosampler (Agilent Technologies). Cool plasma conditions were used to minimize the argon-based polyatomic interference. The parameters used for the cool plasma were as follows: radio frequency power, 900 W; sample depth, 12 mm; carrier gas flow, 0.92 liter/min; and blend gas flow, 0.9/liter. Cross-flow nebulization was used. The mass spectra were generated by acquiring data for mass 56 for iron, and the concentration of iron in the samples was determined on the basis of the external calibration curve generated with iron standards ranging from 0.5 to 50 μg/liter. Multielement calibration standard-2A (Agilent Technologies), a certified standard, was used to generate the calibration curve.

Bacterial cell surface location of Shp assessed by flow cytometric analysis.

Strain MGAS5005 (serotype M1) was grown in THY and harvested at OD600s of 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8. The bacteria were washed twice with pyrogen-free Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) (Sigma) (pH 7.2) and suspended in DPBS to 108 CFU/ml. Rabbit polyclonal anti-Shp and control antibodies were purchased from Bethyl Laboratories (Montgomery, Tex.). Purified recombinant Shp was used as the antigen and immunoabsorbant for the antibody production and purification. The control antibody raised against a peptide (CARALRSQSEES) which is not encoded by the GAS M1 genome was purified by analogous procedures. Purified polyclonal anti-Shp rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody or control antibody (each at 0.05 μg in 100 μl of DPBS) was added to 100 μl of bacterial suspension and incubated on ice for 30 min, and the cells were washed once with DPBS containing 1% goat serum. The samples were incubated on ice for 30 min with phycoerythrin-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, Pa.) at a dilution of 1:400 in DPBS, washed once with DPBS containing 1% goat serum, and analyzed with a FACScaliber flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.).

Detection of anti-Shp antibodies in sera obtained from mice and humans with invasive GAS infections.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to test for the presence of specific anti-Shp antibodies in human sera. Ninety-six-well Nunc Maxisorp microtiter plates (Fisher Scientific Co., Pittsburgh, Pa.) were coated at 4°C overnight with purified recombinant Shp at a concentration of 0.25 μg/well. The plates were washed four times with PBS containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (Sigma) (PBS-T). The plates were blocked with 100 μl of 0.1% BSA in PBS-T for 2 h at room temperature and washed as described above. The plates were incubated with mouse sera diluted at 1:20 to 1:20,480, or human sera diluted at 1:600, in 0.1% BSA-PBS-T at room temperature for 2 h and washed as described above. The wells were incubated with 1:2,000 goat anti-mouse or anti-human IgG (heavy plus light chains)-peroxidase conjugate (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) in 0.1% BSA-PBS-T at room temperature for 2 h. The plates were washed as described above and washed four times with PBS to remove Tween 20. Washing was performed with a Skanwasher 400 microplate washer (Skatron Instrument, Sterling, Va.). The plates were developed with 100 μl of ABTS [2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid)] solution (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) for 45 min, and the absorbance was measured at 405 nm with a SpectraMax 384 Plus microplate spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, Calif.). Sera obtained from mice infected subcutaneously with MGAS5005 and MGAS315 have been described previously (17). The paired human sera tested were obtained from 5 pharyngitis patients and 28 patients with invasive GAS infections. Acute-phase sera were collected upon diagnosis. Convalescent-phase sera drawn from patients with pharyngitis and invasive infections were obtained at 14 to 28 days and 14 to 257 days after diagnosis, respectively. The invasive strains included serotypes M1 (eight patients); M13 (three patients); M28 (four patients); M58 (two patients); and M3, M11, M22, M36, M61, M75, M89, st1432, st2917, st6735, and st2967 (one patient each). Patients with pharyngitis were infected with strains of serotypes M75 (two patients) and M4, M28, and M73 (one patient each).

Bactericidal activity of blood from mice immunized with Shp.

A direct bactericidal activity assay (4) was used to assess the bactericidal activity of blood obtained from mice immunized with purified recombinant Shp. Four- to 6-week-old female outbred CD-1 Swiss mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, Mass.) were immunized subcutaneously with 50 μg of recombinant Shp in 200 μl of saline emulsified in 44 μl of monophosphoryl lipid A-synthetic trehalose dicorynomycolate (MPL-TDM) adjuvant (Corixa, Hamilton, Mont.). Control mice received saline with the adjuvant. Mice were boosted at weeks 2 and 4 with 50 μg of protein mixed with the adjuvant. Prebleed and immune sera were collected before and 5 days after the first and last immunizations, respectively. Anti-Shp antibody titers were determined with ELISA described as above. Strain MGAS5005 was harvested in exponential phase, washed with sterile PBS, and added to 150 μl of heparinized blood obtained from each control or immunized mouse. The samples were rotated end-to-end at 37°C for 3 h and plated on tryptose agar containing 5% sheep blood, and colonies were counted.

RESULTS

shp gene.

As assessed by hydrophilicity plot analysis, GAS cell surface proteins such as M protein have a typical pattern of a hydrophilic region followed by a hydrophobic region at the amino terminus and a hydrophobic region followed by a hydrophilic region at the carboxy terminus. This pattern is caused by the presence of a secretion signal sequence at the amino terminus and a putative transmembrane domain and charged tail at the carboxy terminus. Analysis of an available GAS M1 genome (http://genome.ou.edu/strep.html) identified 19 open reading frames (ORFs) encoding proteins with this type of pattern. One inferred protein encoded by ORF spy1796 did not have the LPXTG motif or variants of this motif characteristically present in cell surface proteins of gram-positive bacteria (9) and was chosen for further analysis. With the exception of Streptococcus equi and other strains of GAS, this gene (spy1796, designated shp) does not have significant homologues in public microbial genome databases, including 100 completed and unfinished genome sequences (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Microb_blast/unfinishedgenome.html). The inferred amino acid sequence of Shp encoded by the M1 genome is 49% identical to that of the S. equi homologue. The inferred Shp protein made by the serotype M1 strain and strains of serotype M5 (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_pyogenes), M3 (unpublished data), and M18 (30) have >99% identity in amino acid sequences, indicating that Shp is highly conserved.

Gene transcript analysis.

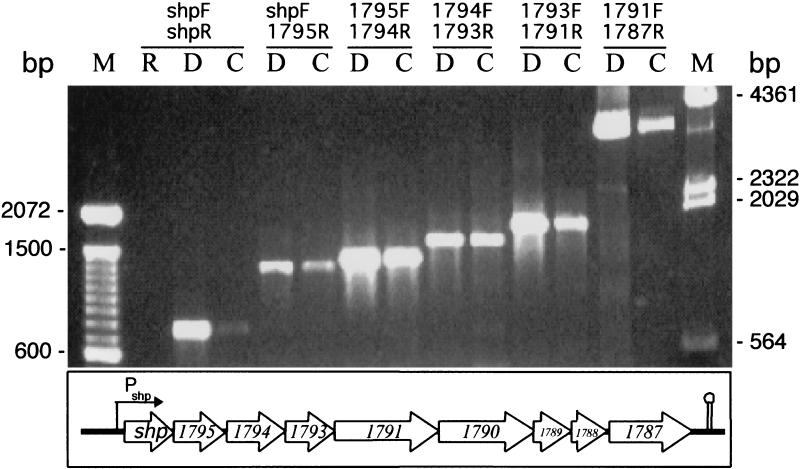

The shp gene is the first ORF of nine contiguous ORFs that are preceded by a potential promoter region and followed by a putative rho-independent terminator (Fig. 1). These ORFs either lack or have very short intergenic sequences, suggesting that they may be cotranscribed. The first upstream and downstream ORFs flanking the cluster were located 196 and 373 bp away, respectively. To determine whether the shp gene is expressed as a single transcript or is part of a polycistronic message, the existence of overlapping amplicons representing the nine genes was assessed by reverse transcription-PCRs using purified mRNA. The results indicated that the nine genes were cotranscribed (Fig. 1). Importantly, no corresponding PCR products were obtained with the same mRNA sample as the template, indicating that the RNA sample was not contaminated with DNA (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Reverse transcription-PCR analysis demonstrating a polycistronic transcript containing shp mRNA. RNA from strain MGAS5005 was reverse transcribed into cDNA, and PCR was done with internal ORF-specific primers. Templates used for PCR were RNA (lane R), DNA (lanes D), and cDNA (lanes C). Forward (F) and reverse (R) primers used for PCR amplification are designated according to the corresponding locus in the sequenced GAS strain SF370. Dashes indicate DNA sizes in the 100-bp ladder (lane M, left) and λ HindIII marker (lane M, right). The schematic shows the arrangement of the genes in strain MGAS5005. A putative promoter (Pshp) and rho-independent terminator (stem-loop structure) were present in the regions upstream and downstream of the gene cluster, respectively.

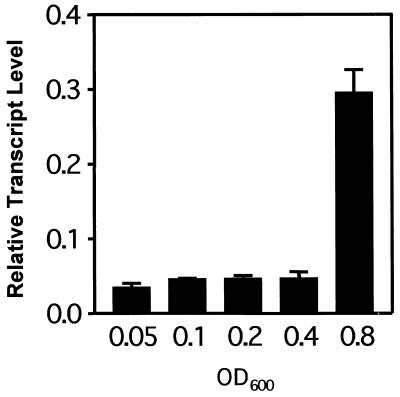

To assess the level of shp transcript present in different growth phases in THY, shp mRNA was quantitated by TaqMan analysis with mRNA obtained from strain MGAS5005 harvested in exponential and early stationary growth phases. The level of shp transcript was low in exponential-phase cells and increased approximately sixfold in early stationary phase (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

TaqMan analysis of shp transcription. TaqMan assays were performed with a probe and primers specific for shp. Cultures of GAS were harvested at OD600s of 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8. The level of shp gene transcript was normalized to the level of transcript derived from gyrA, a gene expressed constitutively throughout the GAS growth cycle (2). The mean level ± standard deviation of triplicate measurements is presented.

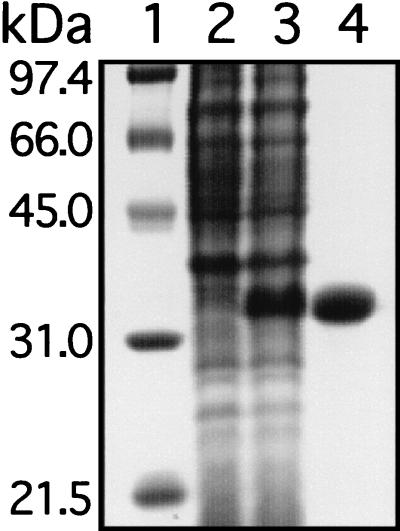

Recombinant Shp protein.

To facilitate production and purification of recombinant Shp protein, a fragment of the spy1796 gene that would encode amino acid residues D30 to D258 was cloned. The resulting protein lacks the putative amino-terminal secretion signal sequence and a putative transmembrane domain and charged tail located at the carboxy terminus. This fragment was cloned to avoid potential toxicity associated with the secretion signal located at the amino terminus and the carboxy-terminal charged tail. The protein was overexpressed in soluble form in E. coli BL21(DE3) and purified to apparent homogeneity (Fig. 3). Amino-terminal amino acid sequencing revealed the expected sequence of MDKGQIYG, confirming the identity of the protein.

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE showing purified recombinant Shp. The gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Lane 1, molecular mass markers; lane 2, E. coli with empty (control) vector; lane 3, E. coli lysate containing Shp; lane 4, purified recombinant Shp.

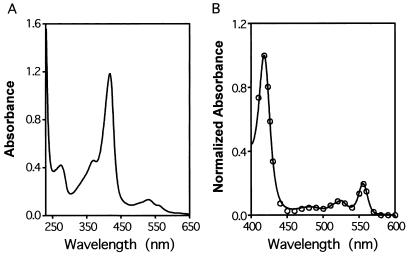

Shp associates with heme.

E. coli BL21 cells expressing the recombinant Shp protein, and the purified recombinant protein, had an intense red color, indicating that Shp has an associated chromophore. The UV-visible absorption spectrum of purified Shp had peaks at 275, 370, 417, 530, and 560 nm (Fig. 4A). These characteristics are typical of heme-binding proteins, suggesting that Shp associates with heme. To confirm that heme is the chromophore associated with this protein, we first used a pyridine hemochrome assay (10). Spectral peaks were observed at 418, 524, and 556 nm and were identical to those obtained for purified M. tuberculosis KatG, a known heme-containing protein (Fig. 4B). The molar ratio of associated heme to recombinant protein was 0.82, a value consistent with the hypothesis that one protein molecule is associated with one heme molecule.

FIG. 4.

Shp binds heme. (A) UV-visible absorption spectrum of 17 μM Shp in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. (B) Reduction spectra of pyridine hemochrome derived from Shp (solid curve) and purified recombinant M. tuberculosis KatG (open circles), as described in Materials and Methods. The spectra were normalized for comparison.

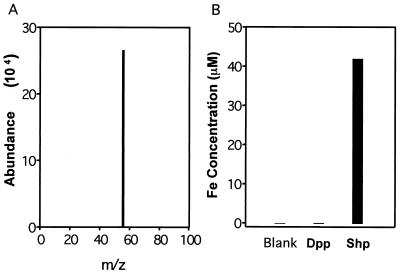

If Shp associates with heme, iron should be present in the chromophore-protein complex. To test this hypothesis, the presence and amount of iron contained in purified Shp was determined by ICP-MS. The results unambiguously showed that iron was present (Fig. 5), whereas other metal ions, such as Zn2+, Co2+, and Cu2+, were not detected. Moreover, iron was not detected in a negative control protein (Spy2000, a putative dipeptide-binding lipoprotein) purified with very similar procedures and the same buffers. We next measured the amount of iron present in the recombinant protein. Shp protein (50 μM) that was purified two independent times contained 35.7 and 40.8 μM iron, results that are consistent with the pyridine hemochrome assay data. The positive control sample containing 50 μM ferric nitrate had an assay value of 37.5 μM Fe. Taken together, the results indicated that recombinant Shp is associated with heme in a 1:1 stoichiometry.

FIG. 5.

Detection of iron associated with purified Shp by ICP-MS. (A) Mass spectrum of 1.7 μM Shp displaying the iron peak at m/z 56. (B) Iron concentrations in blank, 50 μM recombinant streptococcal dipeptide-binding protein (Dpp) (negative control protein), and 50 μM Shp.

In vitro production and cell surface expression of Shp.

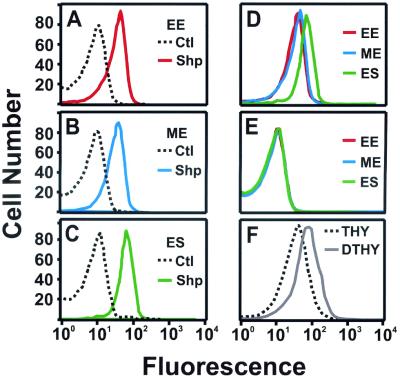

To determine if Shp is produced in vitro and expressed on the GAS cell surface, strain MGAS5005 was grown in THY to early, mid-exponential, and early stationary phases, stained with Shp-specific antibody, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Shp was present on the cell surface at all three growth phases, indicating that Shp is produced in vitro, located on the cell surface, and accessible to specific antibody (Fig. 6). Consistent with the gene transcription analysis, bacteria harvested in stationary phase had increased anti-Shp reactivity relative to those harvested in other growth phases (Fig. 6D).

FIG. 6.

Flow cytometric analysis of in vitro production and cell surface location of Shp. (A to E) MGAS5005 (serotype M1) cells harvested at OD600s of 0.2 (early exponential phase [EE]) (A), 0.4 (mid-exponential phase [ME]) (B), and 0.8 (early stationary phase [ES]) (C) were treated with Shp-specific polyclonal rabbit antibody (solid lines) or control rabbit antibody (dashed lines), stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The results at EE (red), ME (blue), and ES (green) were overlaid, showing a higher fluorescence intensity at ES for bacteria treated with Shp-specific antibody (D) but no fluorescence shift in the control antibody treatment (E). (F) MGAS5005 grown in THY (dashed line) or DTHY (solid line) was harvested at an OD600 of 0.3 and analyzed as described above.

In vivo production of Shp by GAS.

To determine if Shp was produced in vivo during GAS infections, we first measured the anti-Shp titers in sera taken from five mice infected subcutaneously with strain MGAS5005 (serotype M1) or MGAS315 (serotype M3). All mice lacked Shp-specific antibody before inoculation, whereas convalescent-phase sera obtained from mice after infection had a mean anti-Shp antibody titer of 204. We next measured the level of anti-Shp antibody present in acute- and convalescent-phase sera from humans with pharyngitis or invasive GAS infections by ELISA. Twenty-four of 28 patients with invasive GAS disease (infected with strains representing 15 different M types) had significantly higher levels of anti-Shp antibodies in convalescent-phase sera than in acute-phase sera (P = 0.015) (data not shown). The five patients with pharyngitis (infected with strains representing four distinct M protein serotypes) also had significantly higher levels of anti-Shp antibodies in convalescent-phase sera than in acute-phase sera (P = 0.016). These results indicate that Shp is made in mice and humans infected with GAS.

Effect of iron-restricted growth conditions on shp transcription and Shp production.

TaqMan and flow cytometric analyses were used to assess the effect of the iron-restricted growth conditions on shp transcription and Shp production. GAS did not grow in the chelating-resin-treated THY but grew in DTHY supplemented with CaCl2, MgCl2, MnCl2, and ZnCl2. The ratio of the level of shp transcripts in GAS grown in DTHY versus THY was 1.22 ± 0.10 (OD600 = 0.3), indicating enhanced transcription under iron-restricted conditions. Moreover, bacteria grown in DTHY had greater anti-Shp reactivity than GAS grown in THY (Fig. 6F).

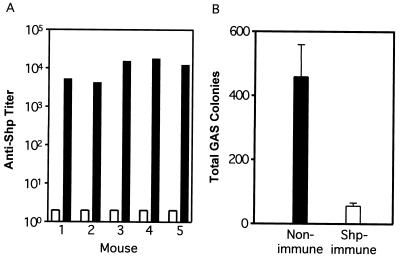

Bactericidal activity of blood from immunized mice.

Inasmuch as Shp is located on the GAS cell surface and accessible to antibody, we tested if anti-Shp antibodies were bactericidal in vitro. Mice were immunized three times with 50 μg of recombinant Shp mixed with the adjuvant MPL-TDM, and anti-Shp titers increased from essentially zero to a mean level of 10,838 (range, 4,170 to 17,530) (Fig. 7A). Consistent with the increase in antibody titers, the results obtained using a standard direct bactericidal activity assay (4) demonstrated that anti-Shp antibody significantly inhibited the in vitro growth of serotype M1 strain MGAS5005 (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

Anti-Shp antibody titers and bactericidal activity of immune mouse blood. (A) The titers of the sera from mice before immunization (open bars) and after the third immunizations (closed bars) were determined by ELISA as described in the text. (B) Direct bactericidal activity. MGAS 5005 bacteria were inoculated in 0.15 ml of heparinized blood from a control mouse (sham immunized) or a mouse actively immunized with Shp. The samples were rotated end-to-end at 37°C for 3 h, and the number of viable bacteria was determined by plating on blood agar plates. The mean colony number ± standard deviation for five mice in each group is presented.

DISCUSSION

Shp is a novel heme-associated protein.

Shp has a UV-visible absorbance spectrum typical of that of heme-containing proteins, and the results of the pyridine hemochrome assay confirmed that the protein is associated with heme. Moreover, measurements of protein, heme, and iron indicated that purified recombinant Shp is a holoprotein that is associated with heme in a 1:1 stoichiometry.

Heme is a major iron source for bacterial pathogens infecting mammals. Many heme-containing proteins have been identified as hemophores or heme receptors that function in iron uptake (11, 34), suggesting that Shp is involved in iron acquisition (see below). However, Shp is not homologous to known heme-binding proteins involved in iron uptake in bacterial pathogens, nor is it homologous to other proteins deposited in public databases. Moreover, bacterial heme-binding proteins are usually surface-exposed lipoproteins, and although Shp is surface exposed, it is not a lipoprotein. Taken together, the data indicate that Shp is the first member of a new class of heme-associated proteins.

Potential involvement of Shp in heme acquisition.

Most bacterial pathogens have one or more complex systems to facilitate acquisition of iron from host environments, which contain little free iron (13). Iron uptake systems in gram-negative bacterial pathogens have been well described, but those in gram-positive organisms are far less well understood. The inferred functions of the genes cotranscribed with shp support the hypothesis that Shp is involved in iron acquisition from the host. Spy1795, a putative lipoprotein containing a secretion signal, is 28.3% identical in amino acid sequence to the conserved domain pfam01479, and Spy1794, a putative permease with multiple transmembrane domains, is 38.5% identical to the consensus amino acid sequence of the conserved domain pfam01032. These two conserved domains are present in ABC transporters involved in iron uptake (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/cdd.shtml) (32). Also cotranscribed with these three genes are inferred homologues of an ATP-binding protein component of an ABC transporter (Spy1793), transporter proteins (Spy1790 and Spy1791) with transmembrane and ATP-binding domains, and another ATP-binding protein characteristic of ABC transporters (Spy1787). Spy1789 has no homologue in public databases, and Spy1788 is homologous to a conserved hypothetical protein of unknown function. On the basis of our experimental results, characteristics of the inferred proteins encoded by genes cotranscribed with the shp gene, and preliminary data indicating that recombinant Spy1795 also binds heme (unpublished data), we propose that Shp functions as a heme receptor located on the GAS cell surface. Under this hypothesis, heme derived from host sources binds to Spy1796 and is then transferred to Spy1795, and bound heme is then taken into the bacterial cell by a process involving Spy1794 and Spy1793. The results of the TaqMan gene transcription analysis and flow cytometry analysis indicate that shp transcription and Shp production are upregulated in the stationary phase of growth in vitro, at a time when it may be especially critical for the organism to acquire iron. Our observation that shp transcription and Shp production are increased under iron-restricted growth conditions is consistent with this idea.

Although heme transport systems in gram-negative bacteria have been extensively characterized (11), heme uptake mechanisms used by gram-positive bacteria are poorly understood. Drazek et al. (5) recently identified an iron acquisition system in Corynebacterium diphtheriae that uses three proteins (HmuT, HmuU, and HmuV) homologous to ABC heme transporters of gram-negative bacteria. An intracellular heme oxygenase (HmuO) is required to liberate iron from the imported heme (36). The C. diphtheriae HmuT and HmuU proteins share the conserved domains pfam01479 and pfam01032 with Spy1795 and Spy1794, respectively. However, this organism is not known to have a homologue of Shp. In addition, hmuO homologues are not present in the available GAS genomes (8; http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_pyogenes), suggesting that heme acquisition and metabolism by GAS have unique features.

The M1 GAS genome encodes three putative ABC transporters which may participate in iron acquisition, including spy1795, spy1794, and spy1793 described in this work; spy0383, spy0384, spy0385, and spy0386 (not yet characterized); and spy0453, spy0454, and spy0456. Proteins encoded by spy0383 to spy0386 are homologous to a ferrichrome ABC transporter, and proteins encoded by spy0453 to spy0456 have been shown to have broad specificity for metal cations (14).

Although little is known about iron acquisition in GAS, Eichenbaum et al. (7) presented evidence that exogenously supplied hemin or host heme-binding proteins (hemoglobin, myoglobin, and catalase) will support in vitro growth but that iron-loaded transferrin, lactoferrin, and cytochrome c will not. These results suggest that heme is an important iron source in vivo for GAS. Preliminary data indicate that recombinant Spy0385 and Spy0453 do not bind heme, whereas Spy1795 does (unpublished data). Hence, proteins encoded by genes in the shp region may be the primary transporters for heme, and the other two transporters might be involved in the acquisition of other nutrients.

In the normal mammalian host, heme is usually bound to proteins such as hemoglobin and myoglobin. To assimilate heme from host heme-protein complexes, bacterial hemophore and heme receptors must have very high affinity for heme. Several lines of evidence suggest that Shp has relatively high affinity for heme. First, the protein clearly can compete successfully with E. coli proteins for heme when grown in vitro. Second, the heme moiety was retained by Shp throughout the purification procedure. Third, greater than 80% of the heme remained bound to Shp after treatment with 8 M urea. Treatment of Shp with 6 M guanidine hydrochloride resulted in increased release of heme, strongly suggesting that the Shp-heme interaction is noncovalent (unpublished results).

Potential role in therapeutics.

Iron is essential for GAS growth and also regulates expression of virulence factors (6, 12, 24, 31). It is therefore reasonable to speculate that inhibition of Shp activity may detrimentally alter the growth of GAS and be therapeutically advantageous. Consistent with this idea, our work showed that active immunization of mice with purified Shp stimulated production of antibodies that significantly inhibited the in vitro growth of GAS, as assessed by a commonly used direct bactericidal activity assay (Fig. 7B). Of note, proteins involved in iron acquisition in other human pathogens are under intense investigation as potential therapeutic targets (1, 15, 19, 27-29, 35). For example, antibodies directed against lipoproteins of two ABC transporters involved in iron uptake in Streptococcus pneumoniae recently were shown to be protective in a mouse infection model (1). Further work will be required to determine if active immunization with iron metabolism proteins will contribute to protective immunity in animal models of GAS infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Low for providing human sera samples, R. Cole for performing the ELISAs, R. Larson for assisting with the animal experiments, and G. Somerville, N. P. Hoe, and F. Gherardini for critical comments.

Editor: E. I. Tuomanen

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown, J. S., A. D. Ogunniyi, M. C. Woodrow, D. W. Holden, and J. C. Paton. 2001. Immunization with components of two iron uptake ABC transporters protects mice against systemic Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Infect. Immun. 69:6702-6706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaussee, M. S., R. O. Watson, J. C. Smoot, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Identification of Rgg-regulated exoproteins of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 69:822-831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham, M. W. 2000. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:470-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dale, J. B., E. Y. Chiang, S. Liu, H. S. Courtney, and D. L. Hasty. 1999. New protective antigen of group A streptococci. J. Clin. Investig. 103:1261-1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drazek, E. S., C. A. Hammack, and M. P. Schmitt. 2000. Corynebacterium diphtheriae genes required for acquisition of iron from haemin and haemoglobin are homologous to ABC haemin transporters. Mol. Microbiol. 36:68-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eichenbaum, Z., B. D. Green, and J. R. Scott. 1996. Iron starvation causes release from the group A Streptococcus of the ADP-ribosylating protein called plasmin receptor or surface glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase. Infect. Immun. 64:1956-1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eichenbaum, Z., E. Muller, S. A. Morse, and J. R. Scott. 1996. Acquisition of iron from host proteins by the group A Streptococcus. Infect. Immun. 64:5428-5429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferretti, J. J., W. M. McShan, D. Ajdic, D. J. Savic, G. Savic, K. Lyon, C. Primeaux, S. Sezate, A. N. Suvorov, S. Kenton, H. S. Lai, S. P. Lin, Y. Qian, H. G. Jia, F. Z. Najar, Q. Ren, H. Zhu, L. Song, J. White, X. Yuan, S. W. Clifton, B. A. Roe, and R. McLaughlin. 2001. Complete genome sequence of an M1 strain of Streptococcus pyogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4658-4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischetti, V. A. 2000. Surface proteins on gram-positive bacteria, p. 11-24. In V. A. Fischetti, R. P. Novick, J. J. Ferretti, D. A. Portnoy, and J. I. Rood (ed.), Gram-positive pathogens. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 10.Fuhrhop, J. H., and K. M. Smith. 1975. Laboratory methods, p. 804-807. In K. M. Smith (ed.), Porphyrins and metalloporphyrins. Elsevier Publishing Co., New York, N.Y.

- 11.Genco, C. A., and D. W. Dixon. 2001. Emerging strategies in microbial haem capture. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffiths, B. B., and O. McClain. 1988. The role of iron in the growth and hemolysin (streptolysin S) production in Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Basic Microbiol. 28:427-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffiths, E., and P. Williams. 1999. The iron-uptake systems of pathogenic bacteria, fungi and protozoa, p. 87-212. In J. J. Bullen and E. Griffiths (ed.), Iron and infection: molecular, physiological and clinical aspects. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Chichester, United Kingdom.

- 14.Janulczyk, R., J. Pallon, and L. Bjorck. 1999. Identification and characterization of a Streptococcus pyogenes ABC transporter with multiple specificity for metal cations. Mol. Microbiol. 34:596-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuboniwa, M., A. Amano, S. Shizukuishi, I. Nakagawa, and S. Hamada. 2001. Specific antibodies to Porphyromonas gingivalis Lys-Gingipain by DNA vaccination inhibit bacterial binding to hemoglobin and protect mice from infection. Infect. Immun. 69:2972-2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lei, B., C.-J. Wei, and S.-C. Tu. 2000. Action mechanism of antitubercular isoniazid: activation by Mycobacterium tuberculosis KatG, isolation, and characterization of InhA inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 275:2520-2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lei, B., S. Mackie, S. Lukomski, and J. M. Musser. 2000. Identification and immunogenicity of group A Streptococcus culture supernatant proteins. Infect. Immun. 68:6807-6818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lei, B., F. R. DeLeo, N. P. Hoe, M. R. Graham, S. M. Mackie, R. L. Cole, M. Liu, H. R. Hill, D. E. Low, M. J. Federle, J. R. Scott, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Evasion of human innate and acquired immunity by a bacterial homologue of CD11b that inhibits opsonophagocytosis. Nat. Med. 7:1298-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lissolo, L., G. Maitre-Wilmotte, P. Dumas, M. Mignon, B. Danve, and M.-J. Quentin-Millet. 1995. Evaluation of transferrin-binding protein 2 within the transferrin-binding protein complex as a potential antigen for future meningococcal vaccines. Infect. Immun. 63:884-890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowry, O. H., N. J. Rosebrough, A. L. Farr, and R. J. Randall. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265-275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lukomski, S., S. Sreevatsan, C. Amberg, W. Reichardt, M. Woischnik, A. Podbielski, and J. M. Musser. 1997. Inactivation of Streptococcus pyogenes extracellular cysteine protease significantly decreases mouse lethality of serotype M3 and M49 strains. J. Clin. Investig. 99:2574-2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lukomski, S., C. A. Montgomery, J. Rurangirwa, R. S. Geske, J. P. Barrish, G. J. Adams, and J. M. Musser. 1999. Extracellular cysteine protease produced by Streptococcus pyogenes participates in the pathogenesis of invasive skin infection and dissemination in mice. Infect. Immun. 67:1779-1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lukomski, S., N. P. Hoe, I. Abdi, J. Rurangirwa, P. Kordari, M. Liu, D. Shu-Jun, G. G. Adams, and J. M. Musser. 2000. Nonpolar inactivation of the hypervariable streptococcal inhibitor of complement gene (sic) in serotype M1 Streptococcus pyogenes significantly decreases mouse mucosal colonization. Infect. Immun. 68:535-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McIver, K. S., A. S. Heath, and J. R. Scott. 1995. Regulation of virulence by environmental signals in group A streptococci: influence of osmolarity, temperature, gas exchange, and iron limitation on emm transcription. Infect. Immun. 63:4540-4542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Musser, J. M., A. R. Hauser, M. H. Kim, P. M. Schlievert, K. Nelson, and R. K. Selander. 1991. Streptococcus pyogenes causing toxic shock-like-syndrome and other invasive diseases: clonal diversity and pyrogenic exotoxin expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:2668-2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Musser, J. M., and R. M. Krause. 1998. The revival of group A streptococcal diseases with a commentary on staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome, p. 185-218. In R. M. Krause, and A. Fauci (ed.), Emerging infections. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 27.Myers, L. E., Y.-P. Yang, R.-P. Du, Q. Wang, R. E. Harkness, A. B. Schryvers, M. Myers, H. Klein, and S. M. Loosmore. 1998. The transferrin binding protein B of Moraxella catarrhalis elicits bactericidal antibodies and is a potential vaccine antigen. Infect. Immun. 66:4183-4192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Potter, A. A., A. B. Schryvers, J. A. Ogunnariwo, W. A. Hutchins, R. Y. C. Lo, and T. Watts. 1999. Protective capacity of the Pasteurella haemolytica transferrin-binding proteins TbpA and TbpB in cattle. Microb. Pathog. 27:197-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rokbi, B., M. Mignon, G. Maitre-Wilmotte, L. Lissolo, B. Danve, D. A. Caugant, and M.-J. Quentin-Millet. 1997. Evaluation of recombinant transferrin-binding protein B variants from Neisseria meningitidis for their ability to induce cross-reactive and bactericidal antibodies against a genetically diverse collection of serogroup B strains. Infect. Immun. 65:55-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smoot, J. C., K. D. Barbian, J. J. Van Gompel, L. M. Smoot, M. S. Chaussee, G. L. Sylva, D. E. Sturdevant, S. M. Mackie, S. F. Porcella, L. D. Parkins, S. B. Beres, D. S. Campell, T. M. Smith, Q. Zhang, V. Kapur, J. A. Daly, L. G. Veasy, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Genome sequence and comparative microarray analysis of serotype M18 group A Streptococcus strains associated with acute rheumatic fever outbreaks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:4668-4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smoot, L. M., J. C. Smoot, M. R. Graham, G. A. Somerville, D. E. Sturdevant, C. A. Migliaccio, G. L. Sylva, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Global differential gene expression in response to growth temperature alteration in group A Streptococcus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:10416-10421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staudenmaier, H., B. van Hove, Z. Yaraghi, and V. Braun. 1989. Nucleotide sequences of the fecBCDE genes and locations of the proteins suggest a periplasmic-binding-protein-dependent transport mechanism for iron(III) dicitrate in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 171:2626-2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sutcliffe, I. C., and R. R. B. Russell. 1995. Lipoproteins of gram-positive bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 177:1123-1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wandersman, C., and I. Stojilkovic. 2000. Bacterial heme sources: the role of heme, hemoprotein receptors and hemophores. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:215-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.West, D., K. Reddin, M. Matheson, R. Heath, S. Funnell, M. Hudson, A. Robinson, and A. Gorringe. 2001. Recombinant Neisseria meningitidis transferrin binding protein A protects against experimental meningococcal infection. Infect. Immun. 69:1561-1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilks, A., and M. P. Schmitt. 1998. Expression and characterization of a heme oxygenase (HmuO) from Corynebacterium diphtheriae: iron acquisition requires oxidative cleavage of the heme macrocycle. J. Biol. Chem. 273:837-841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]