The past decade has seen much progress in our understanding of the cellular mechanisms responsible for renal tubular acidosis (RTA), although the mechanism of the common complication of nephrocalcinosis remains unclear. In this brief overview, we discuss RTA from the standpoint of applied or ‘clinical’ renal tubular physiology, since this represents a synthesis of over 50 years of clinical description and classification, more than 30 years of segmental renal tubular physiology, and almost 10 years of applied molecular genetics. We begin by defining RTA and its current clinical classification, and we review this in the context of normal urinary acidification and how it might go wrong.

DEFINITION

RTA signifies an inability of the kidney to excrete adequately an acid (H+) load and so contribute to maintaining normal acid—base balance. Defined in this way, it could also include the low acid excretion of renal failure, but RTA is distinguished from uraemic acidosis by a normal or only slightly reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and a hyperchloraemic normal (rather than increased) anion gap metabolic acidosis—the only other important cause of which is loss of alkali (bicarbonate) from diarrhoea. In uraemic acidosis H+ excretion per functioning nephron is increased; the underlying cellular mechanisms of H+ secretion are preserved and responding normally to a systemic acid-load that cannot be excreted because of too few nephrons1.

The current classification of RTA can be confusing, especially the older terminology of ‘types’, which was originally chronological (Box 1). This terminology gives no hint as to the process of renal acid excretion and therefore to the potentially defective underlying cellular mechanism2. Advances in renal physiology, and most recently in molecular genetics as applied to renal tubular cell physiology, have now made it possible to describe RTA in more functional terms and even to predict likely causes. To illustrate this, we must first describe how the kidney maintains long-term acid—base balance.

Box 1.

Current ‘clinical’ classification of renal tubular acidosis (RTA)

| • Type 1: Distal RTA (most common)—‘complete’ and ‘incomplete’ (hypokalaemia common) |

| • Type 2: Proximal RTA |

| • Type 3: A poorly characterized mixture of 1 and 2 in infants and which may reflect an ‘immature’ renal tubule |

| • Type 4: Hypoaldosteronism (real or apparent)—‘distal-like’ with hyperkalaemia |

RENAL ACID EXCRETION

The following equation, a loose version of the Henderson—Haselbalch relationship, highlights the kidney's critical role in bicarbonate balance as well as its place in normal acid—base balance3:

|

What determines the presence of systemic acidosis is summarized in Box 2. To produce urine that is normally acid relative to blood, the kidney must excrete net acid (ingested and metabolically generated H+ of around 40-70 mmol/day, depending on diet)—a process facilitated by the main urinary buffers of phosphate and ammonium (NH4+)—and must reclaim filtered bicarbonate. The main sites of H+ secretion that sustain these two components of acid—base balance are the proximal and distal tubules, where the reclamation of filtered bicarbonate and the excretion of net acid occur, respectively; these nephron sites are also the basis of proximal versus distal RTA (Figure 1).

Box 2.

What determines acidosis?

| • H+ intake and endogenous H+ generation |

| • H+ excretion (TA+NH4+ - HCO3-) |

| TA (mainly phosphate) is dependent on urine pH and the amount of buffer available (i.e. phosphate balance) |

| NH4+ is dependent on NH3/NH4+ generation and delivery (PT, TAL reabsorption and CD ‘trapping’) |

| HCO3- is dependent on urine pH and pCO2 |

| TA=titratable acid; PT=proximal tubule; TAL=thick ascending limb; CD=collecting duct |

Figure 1.

Main sites of H+ secretion

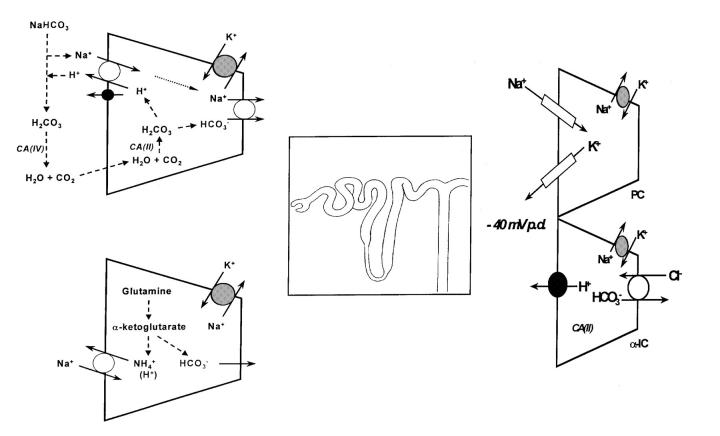

Figure 2 shows the major pathways of acidification along the renal tubule. At each site the secreted H+ is generated inside the renal tubular cell from CO2 and H2O, catalysed by the enzyme carbonic anhydrase (CA-II). This enzyme is especially important along the proximal tubule, where its presence on the luminal cell membrane surface (as another isoform, CA-IV) promotes the combination of filtered bicarbonate with secreted H+ by dehydrating the carbonic acid (H2CO3) produced, leading to net bicarbonate reabsorption (via CO2 diffusion).

Figure 2.

Current cellular models of tubule acidification (proximal versus distal). CA=carbonic anhydrase; PC=principal cell; α-IC=intercalated cell; p.d.=potential difference

In addition to secreting H+, the proximal tubular cells can generate new bicarbonate from the metabolism of glutamine, which also produces ammonium (NH4+), the key urinary buffer (see Box 2). Ammonium reaches the urine by a complex route that involves proximal tubular secretion, subsequent reabsorption along the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle and lastly diffusion trapping within the collecting duct lumen and so to the final urine. Its journey to urine can be disrupted at each step and thereby impair net acid excretion, even when cellular H+ secretion is normal. As an example, hyperkalaemia (especially when due to a lack of aldosterone, see Box 1) can reduce acid excretion by inhibiting NH4+ production4.

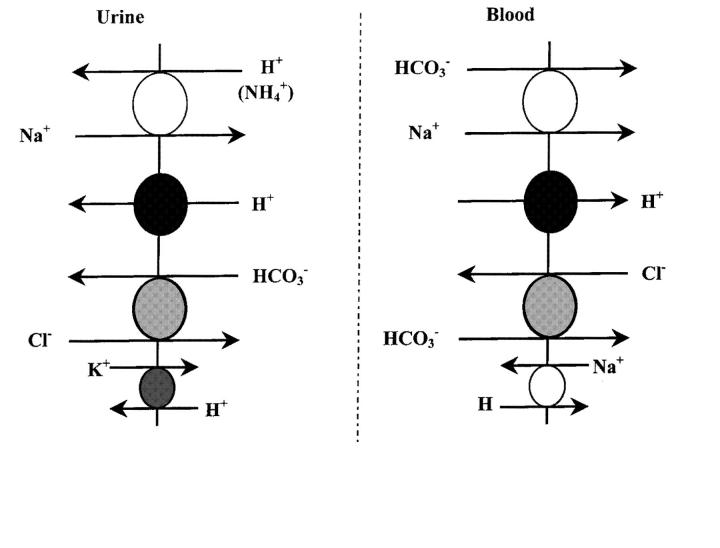

The actual mechanisms of cellular H+ secretion described so far are illustrated in Figure 3. In the proximal tubule most of the H+ secretion is coupled to Na+ absorption via the Na+-H+ exchanger (which also transports NH4+ to secrete it from the proximal tubular cells) of which several isoforms have been cloned5,6. Isoform 3 (NHE-3) appears to be the main transporter responsible for luminal H+ (and NH4+) secretion7, but so far has not been linked to a form of clinical RTA. In addition to the Na+-H+ exchanger there is an Na+-independent H+ secretory mechanism, the electrogenic H+-ATPase8, although this ‘proton pump’ is functionally much more important in H+ secretion along the distal tubule and collecting duct, where its activity also depends on aldosterone.

Figure 3.

Acid-base renal tubular cell membrane transporters

To achieve luminal H+ secretion, bicarbonate must leave the cell across the opposite (basolateral) cell membrane. In the proximal tubule this is mainly via the Na+-HCO3- co-transporter, whereas in the distal nephron (distal tubule and collecting duct) it is via the Cl--HCO3- exchanger. Each of the transporters shown in Figure 3 is a potential target in acquired or inherited forms of RTA. However, to date only the H+-ATPase9,10,11,12, Cl--HCO3- exchanger13,14,15,16 and Na+-HCO3- co-transporter17 have been causally linked to RTA, largely on the basis of studies of inherited RTA (Box 3). Defective H+ secretion (direct or secondary to reduced bicarbonate transport) is only one potential mechanism of RTA; others are set out in Box 4.

Box 3.

Inherited forms of renal tubular acidosis

| Proximal |

| • Various metabolic disorders with or without the Fanconi syndrome |

| • CA(II) mutation(s)—autosomal recessive* (Ref 18) |

| • Na+-HCO3- (NBC-SLC4A4) mutation(s)—autosomal recessive (Ref 17) |

| Distal |

| • Cl--HCO3- (AE1-SLC4A2) mutation(s)—autosomal dominant (Ref 14) |

| • H+-ATPase (B1 subunit) mutation(s)—autosomal recessive with deafness (Ref 11) |

| CA=carbonic anhydrase; *Can also be distal-like |

Box 4.

Mechanisms of renal tubular acidosis

| • Failure of tubular cell ion transport (H+ or HCO3-)—including the electrical (voltage) driving force (low aldosterone, amiloride-induced) |

| • Failure of H+ generation (e.g. lack of carbonic anhydrase) |

| • ‘Leaky’ apical (luminal) cell membrane (e.g. amphotericin-induced) |

| • Failure of NH4+ generation or ‘circulation’ within the kidney (e.g. hyperkalaemia-induced) |

DIAGNOSIS

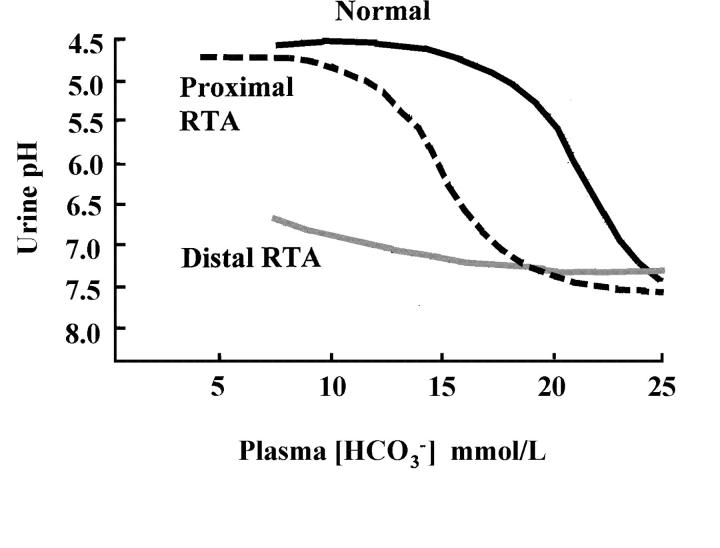

An important clue in RTA is the relationship between plasma bicarbonate concentration and urine pH. In proximal RTA, bicarbonate is lost in the urine and urine pH may initially be high but will fall to <5.5 as the plasma bicarbonate concentration decreases; in contrast, in distal RTA, urine pH remains raised despite a low plasma bicarbonate (Figure 4). The diagnosis of RTA is usually suspected when the urine pH is inappropriately, or persistently, alkaline; but remember that urine pH also depends on time of day and diet. A more useful random or spot urine pH value is that of an early morning urine sample (second void), when acid excretion is usually maximal and pH normally <5.5. A ‘clinic’ dipstick urine pH is a very rough guide and is often unreliable: urine pH must be measured with a pH electrode soon after voiding; if urine is left standing or there is infection, it can be misleadingly high, at 8 or more.

Figure 4.

Urine pH versus plasma bicarbonate in renal tubular acidosis (RTA) (adapted from Refs 19 and 31)

In proximal RTA, urine pH may be high or appropriately low, depending on the plasma bicarbonate concentration (see earlier). In the absence of other clues suggesting a Fanconi-like defect of proximal tubular function, such as glycosuria, aminoaciduria, phosphate wasting, or tubular (low-molecular-weight) proteinuria, it may be necessary to do intravenous bicarbonate loading and measure the fractional excretion of bicarbonate. Normally urinary bicarbonate is barely detectable and fractional excretion is <5% of the (glomerular) filtered load, but in proximal RTA it is usually around 15%. In distal RTA, urine pH will be high, but plasma bicarbonate concentration can be low (‘complete distal RTA’) or normal (‘incomplete distal RTA’)20. For a clear demonstration of impaired renal net acid excretion a urinary acidification test must be done, either by acute administration of an acid load as oral ammonium chloride (NH4Cl, 0.1 g/kg)21 or by the combination of oral fludrocortisone (0.1 mg) and frusemide (40 mg)22. In both tests urine pH is measured as urine is voided for at least 5 hours; in the NH4Cl test, up to 8 hours may be necessary because of the time needed to ingest it without nausea or vomiting. A normal response is a fall in urine pH at some point to <5.5.

Underlying distal RTA is an important cause of nephrocalcinosis and renal stone disease. In the most comprehensive clinical series published, Wrong23 reported that approximately 20% of over 300 patients with nephrocalcinosis had underlying distal RTA, inherited or acquired. Of the inherited type most were dominantly inherited, and of the acquired type most were autoimmune (e.g. Sjögren's syndrome)9,24. It is therefore important to consider the possibility of distal RTA in any patient with renal stones, particularly if nephrocalcinosis is also present. A diagnosis of medullary sponge kidney (MSK) is often incorrectly made when renal medullary calcification is seen on a plain abdominal X-ray. MSK is a radiological diagnosis and depends on identifying ectatic terminal collecting ducts on intravenous urography. However, the associated calcification and medullary damage (and loss of normal collecting duct function) can produce a secondary form of distal RTA. In isolated nephrocalcinosis in women, the cause is often autoimmune and the condition is commonly associated with symptomatic hypokalaemia23.

The reason for nephrocalcinosis and renal stones in RTA is not completely understood, but hypercalciuria (usually confined to those patients with systemic acidosis) and low urinary excretion of citrate are important factors. Indeed a low urinary citrate concentration in the presence of an alkaline pH is an important clue to underlying distal RTA, since there is normally a direct relationship between urinary citrate concentration and urine pH. Citrate reaches the urine by filtration but is partly reabsorbed in the proximal tubule, where its absorption depends on pH, systemic and intracellular, such that acidosis increases citrate reabsorption and also its intracellular metabolism25. It is probably for this reason that kidney stones and nephrocalcinosis are less common in proximal RTA: citrate reabsorption is often reduced and urinary citrate excretion increased, although this may be offset by any associated hypokalaemia and intracellular acidosis. In distal RTA, systemic and/or intracellular acidosis leads to increased citrate reabsorption in the proximal tubule and thus reduced urinary citrate excretion; hence a potential benefit of alkali therapy in correcting this.

As already mentioned, hypokalaemia is often associated with RTA. In proximal RTA, the most likely reason is the increase in bicarbonate delivery and flow rate to the main site of K+ secretion, the distal nephron. However, there is no clear explanation for the hypokalaemia commonly observed in distal RTA. In both forms of RTA, treatment with oral bicarbonate or citrate (which is converted to bicarbonate in the liver) tends to exacerbate the hypokalaemia.

TREATMENT OF RTA

The main reasons for treatment are to protect the bones and help heal rickets or osteomalacia in those patients with metabolic acidosis, and to promote citrate excretion, which may reduce the risk of renal stones and progression of nephrocalcinosis26. Box 5 lists common management strategies. Ideally, in those patients with metabolic acidosis, plasma bicarbonate concentration should be maintained above 20 mmol/L. In proximal RTA, a thiazide diuretic can be helpful by causing mild volume depletion, which enhances proximal tubular reabsorption of bicarbonate; however, as with bicarbonate supplements, it will increase the tendency to hypokalaemia.

Box 5.

Management of renal tubular acidosis

| • Alkali therapy in small doses: 1-2 mmol/kg, target plasma [HCO3-]>20 mmol/L |

| to heal bones |

| to prevent stones/limit progression of nephrocalcinosis |

| • K+ supplements may be necessary |

| • Vitamin D may be necessary |

| • Thiazide diuretics may help in proximal form |

| • Long-term follow-up for renal stone complications |

THE FUTURE

Monogeneic disorders of renal tubular function will continue to provide insights into the complexities and subtleties of urinary acidification, even when RTA is not the main clinical feature. For example, the tubulopathy now known as Dent's disease, genetically characterized by Thakker27 and co-workers, can sometimes be confused with distal RTA. Its mutated protein, an intracellular Cl- channel, ClC-5, may regulate H+ secretion by a mechanism akin to that well-described for water channels (aquaporin 2)28, with insertion and retrieval of proton pumps into the luminal plasma membrane—an interpretation that may also be consistent with a recent finding by Karet et al.12 in a recessively inherited form of distal RTA.

The puzzle of exactly how and why nephrocalcinosis occurs in distal RTA remains unsolved. Now that specific H+ transporter defects are known to be important in clinical RTA, it should be possible to reproduce such abnormalities in isolated renal collecting duct cells and study the process of microcrystallization leading to nephrocalcinosis and renal stone formation.

Finally, knowledge of the gene targets holds out the prospect of gene therapy29,30, not just for those with inherited defects of renal acidification, but also as supplementary therapy in those with secondary forms of RTA and renal stone disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor O M Wrong for many valuable discussions and the Wellcome Trust for collaborative support.

References

- 1.Madias NE, Kraut JA. Uremic acidosis. In Seldin DW, Giebisch G, eds. The Regulation of Acid—Base Balance. New York: Raven Press, 1989: 285-317

- 2.Kamel KS, Briceno LF, Sanchez MI, et al. A new classification for renal defects in net acid excretion. Am J Kidney Dis 1997;29: 136-46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boron WF. Chemistry of buffer equilibria in blood plasma. In Seldin DW, Giebisch G, eds. The Regulation of Acid-Base Balance. New York: Raven Press, 1989: 3-32

- 4.DuBose TDJ. Hyperkalemic metabolic acidosis. Am J Kidney Dis 1999;33: XLV-XLVIII [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alpern RJ. Cell mechanisms of proximal tubule acidification. Physiol Rev 1990;70: 79-114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amemiya M, Loffing J, Lotscher M, et al. Expression of NHE-3 in the apical membrane of rat renal proximal tubule and thick ascending limb. Kidney Int 1995;48: 1206-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang T, Yang CL, Abbiati T, et al. Mechanism of proximal tubule bicarbonate absorption in NHE3 null mice. Am J Physiol 1999;277: F297-F302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gluck SL, Underhill DM, Iyori M, Halliday LS, Kostrominova TY, Lee BS. Physiology and biochemistry of the kidney vacuolar H+ATPase. Annu Rev Physiol 1996;58: 427-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen EP, Bastani B, Cohen MR, Kolner S, Hemken P, Gluck SL. Absence of H(+)ATPase in cortical collecting tubules of a patient with Sjogren's syndrome and distal renal tubular acidosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 1992;3: 264-711391725 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jordan M, Cohen EP, Roza A, et al. An immunocytochemical study of H+ ATPase in kidney transplant rejection. J Lab Clin Med 1996;127: 310-14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karet FE, Finberg KE, Nelson RD, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding BI subunit of H+-ATPase cause renal tubular acidosis with sensorineural deafness. Nat Genet 1999;21: 84-90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith AN, Skaug J, Choate KA, et al. Mutations in ATP6NIB, encoding a new kidney vacuolar proton pump 116-kD subunit, cause recessive distal renal tubular acidosis with preserved hearing. Nat Genet 2000;26: 71-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karet FE, Gainza FJ, Gyory AZ, et al. Mutations in the chloride-bicarbonate exchanger gene AE1 cause autosomal dominant but not autosomal recessive distal renal tubular acidosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998;95: 6337-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruce LJ, Cope DL, Jones GK, et al. Familial distal renal tubular acidosis is associated with mutations in the red cell anion exchanger (Band 3, AE1) gene. J Clin Invest 1997;100: 1693-707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarolim P, Shayakul C, Prabakaran D, et al. Autosomal dominant distal renal tubular acidosis is associated in three families with heterozygosity for the R589H mutation in the AE1 (band 3) Cl-/HCO3-exchanger. J Biol Chem 1998;273: 6380-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamphaichitr VS, Sumboonnanonda A, Ideguchi H, et al. Novel AE1 mutations in recessive distal renal tubular acidosis. Loss-of-function is rescued by glycophorin A. J Clin Invest 1998;102: 2173-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Igarashi T, Inatomi J, Sekine T, et al. Mutations in SLC4A4 cause permanent isolated proximal renal tubular acidosis with ocular abnormalities. Nat Genet 1999;23: 264-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sly WS, Hewett-Emmett D, Whyte MP, Yu YS, Tashian RE. Carbonic anhydrase II deficiency identified as the primary defect in the autosomal recessive syndrome of osteopetrosis with renal tubular acidosis and cerebral calcificatioin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1983;80: 2752-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soriano JR, Boichis H, Edelmann CM, Jr. Bicarbonate reabsorption and hydrogen ion excretion in children with renal tubular acidosis. J Pediatr 1967;71: 802-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wrong OM, Feest TG. The natural history of distal renal tubular acidosis. Contrib Nephrol 1980;21: 137-44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wrong O, Davies HEF. The excretion of acid in renal disease. Q J Med 1959;28: 259-313 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walter SJ, Shirley DG, Unwin RJ, Wrong OM. Assessment of urinary acidification. Kidney Int 1999;55: 2092A [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wrong O. Nephrocalcinosis. In: Cameron S, Davison AM, Grunefeld J-P, Kerr DS, Ritz E, eds. Oxford Textbook of Nephrology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998: 1375-96

- 24.DeFranco PE, Haragsim L, Schmitz PG, Bastania B. Absence of vacuolar H(+)-ATPase pump in the collecting duct of a patient with hypokalemic distal renal tubular acidosis and Sjögren's syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 1995;6: 295-301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamm LL. Renal handling of citrate. Kidney Int 1990;38: 728-35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richards P, Chamberlain MJ, Wrong OM. Treatment of osteomalacia of renal tubular acidosis by sodium bicarbonate alone. Lancet 1972;ii: 994-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lloyd SE, Pearce SH, Fisher SE, et al. A common molecular basis for three inherited kidney stone diseases. Nature 1996;379: 445-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nielsen S, Kwon TH, Christensen BM, Promeneur D, Frokiaer J, Marples D. Physiology and pathophysiology of renal aquaporins. J Am Soc Nephrol 1999;10: 647-63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai LW, Chan DM, Erickson RP, Hsu SJ, Lien YH. Correction of renal tubular acidosis in carbonic anhydrase II-deficient mice with gene therapy. J Clin Invest 1998;101: 1320-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lien YH, Lai LW. Liposome-mediated gene transfer into the tubules. Exp Nephrol 1997;5: 132-6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]