Abstract

A major advance has been made towards the positional cloning of char2 (a quantitative trait locus encoding resistance to Plasmodium chabaudi malaria). Mice congenic for the locus have been used to fine map the gene and to prove that char2 plays a significant role in the outcome of malarial infection, independently of other resistance loci.

Malaria is a parasitic disease afflicting over 300 million people worldwide and is the cause of death for approximately 1 million people each year (WHO Malaria Fact Sheet, http://www.who.int/int-fs/en/fact094.html). However, little is understood about the genetics of the host response to the disease. We aim to clone and characterize the genes that are involved in this process to elucidate the molecular differences between resistant and susceptible individuals. Potentially, this will lead to the development of new and innovative approaches to the treatment of this disease.

In a previous study, we used a murine model of malarial infection to successfully map three quantitative trait loci (QTL), char1, char2, and char3, that are strongly linked to host survival and parasite levels (1-3). This paper reports a major advance towards the positional cloning of char2. By characterizing a panel of char2-congenic mice, we refined the map position of the locus on chromosome 8 and demonstrated that it can influence the outcome of malarial infection independently of all other host response loci.

A “speed” congenic approach was used to generate the panel of char2-congenic mice (5, 7). A congenic animal is one that has inherited an allele from one inbred strain at a locus of interest, on a background genome derived from a second, inbred strain (6). This involves performing serial backcrosses between two inbred strains that carry different alleles at the locus of interest. In this case, C3H/He (which succumbs to malaria) and C57BL/6 (which survives malaria) were selected as the parental inbred lines. At each generation, offspring were screened with microsatellite markers in order to select the most desirable animals for breeding the following generation (genotyping was performed as previously described [1]). Animals carrying the genotype of interest at char2 that also possessed the fewest undesired alleles in the background genome were selected. At each of the N2, N3, and N4 generations, 30-centimorgan genome scans were performed on approximately 25 male offspring. The scans were performed with offset panels of markers (selected from the MIT database [http://www.genome.wi.mit.edu/] and purchased from Research Genetics), such that the lines were screened at an overall resolution of approximately 10 centimorgans throughout the genome. Subsequent generations were screened at the char2 locus and at other chromosomal regions where the genotype of the background genome had not yet become fixed. Each line was intercrossed at the N7 or N8 generation to produce homozygotes.

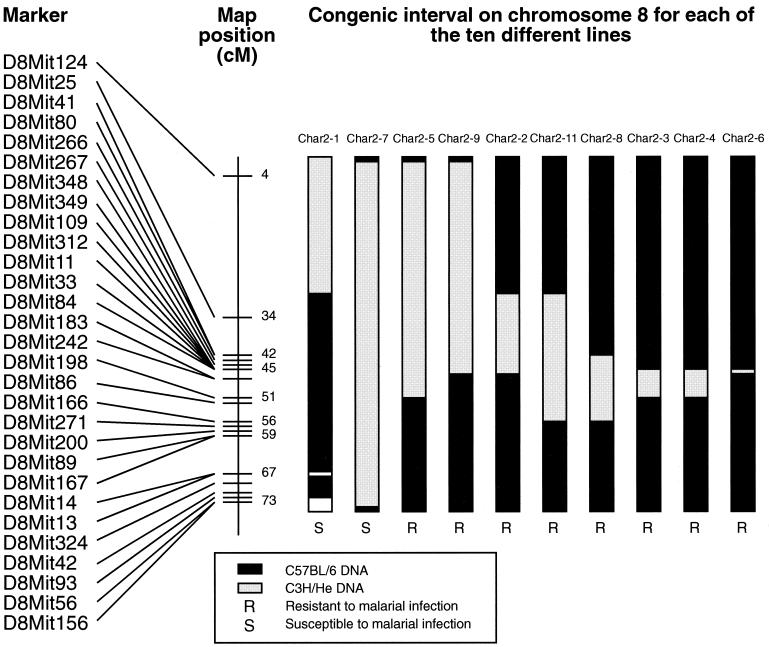

A total of 10 char2 congenic lines were produced, each carrying a different recombinant interval around the char2 locus (Fig. 1). The combinations of different congenic intervals span most of the chromosome, and the recombinations have been well defined by using microsatellite markers. Thus, the panel of animals should also prove a useful resource for the study of other loci on murine chromosome 8.

FIG. 1.

Illustration of the genotype at a selection of microsatellite markers on chromosome 8, inherited by each of the 10 different char2 congenic mouse strains. Congenic line char2-1 is the only line with a C3H/He background genome. All other lines carry a C57BL/6 background genome. The map position (in centimorgans [cM]) of the markers was obtained from the MGI database (http://www.informatics.jax.org/). The map order of the markers, as illustrated here, is based on recombinations observed during breeding of the congenic lines.

Animals from each line were challenged with Plasmodium chabaudi to determine their response to infection. Mice were infected with malaria by intravenous injection of 104 parasitized red blood cells (RBCs). The mice were monitored for 16 days postinfection, and both survival and parasitemia levels experienced by the animals were noted (the percentage of parasitized RBCs was calculated for each animal on each day of the infection by counting 300 RBCs from a Giemsa-stained thin smear). This method is described in more detail elsewhere (1).

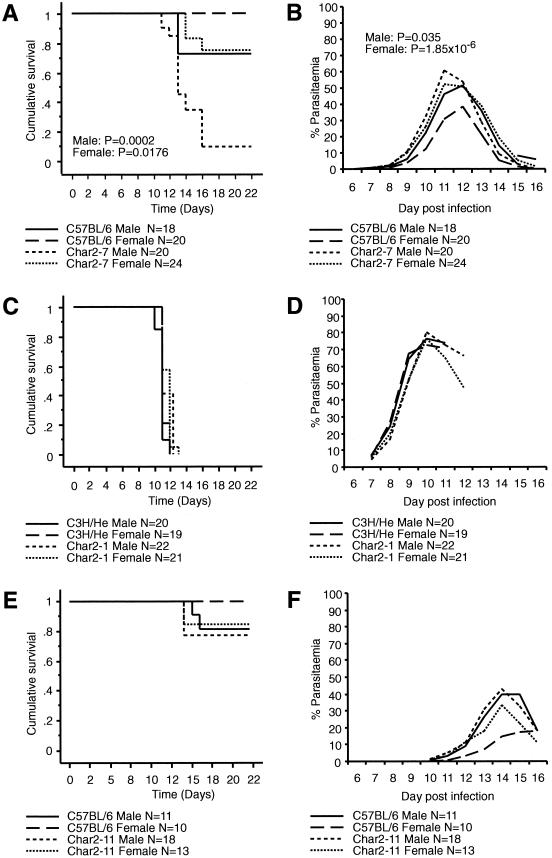

C57BL/6.C3H/He(7)-char2 (char2-7) animals were found to be more susceptible to malaria than C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 2A). The char2-7 animals also experienced much higher parasite levels than the controls throughout the infection (Fig. 2A). These differences are most evident in male animals. Interestingly, animals from the reciprocal congenic line C3H/He.C57BL/6(1)-char2 (char2-1) had the same response to malarial infection as C3H/He controls (Fig. 2B). Similarly, none of the other congenic lines differed significantly from parental controls. As an example, survival curves for C57BL/6.C3H/He(11)-char2 (char2-11) versus C57BL/6 animals are displayed in Fig. 2C.

FIG. 2.

Outcome of infection in char2 congenic animals and control mice following intravenous injection with 104 P. chabaudi-parasitized red blood cells (RBCs). (A and B) Results of infection of char2-7 congenic animals versus C57BL/6 controls; (C and D) results of infection of char2-1 congenic mice versus C3H/He controls; (E and F) results of infection of char2-11 congenic animals versus C57BL/6 controls. (A, C, and E) Kaplan-Meier cumulative survival plots for congenic mice versus controls. Significant P values (A) are the results of Mantel-Cox analyses of the difference between two curves. Males and females were analyzed separately. (B, D, and F) Plots of the average course of infection for congenic mice versus controls. Significant P values (B) are the results of t tests comparing the peak levels of parasitemia in congenic mice with those in controls. Males and females were considered separately.

These results suggest that the char2-7 congenic interval spans the char2 gene whereas the char2-11 congenic interval does not. However, since the char2-7 congenic interval is quite large, there is always the possibility that the char2 locus comprises several genes that interact to influence survival of a malarial infection. Even without specifying a single-gene or multigene scenario, comparison of these two congenic intervals places at least one char2 gene within the interval bounded by D8Mit166 and D8Mit156. This segment of chromosome 8 is encompassed by the char2-7 congenic interval, which confers susceptibility, and is not included in the char2-11 congenic interval, which does not affect response to malarial infection (Fig. 1). The interval is located slightly distal to the QTL map position that was defined for this locus. This is not inconsistent with the idea that the Lander and Botstein (4) algorithm for QTL mapping is unlikely to pinpoint the position of a QTL if it is linked to other QTL (8).

The dissection of this complex phenotype, regulated by multiple genes, into a single locus model was quite unexpected. Indeed, inheritance of the C3H/He genotype at this locus is sufficient to significantly decrease an animal's chance of surviving a malarial infection. Interestingly, inheritance of a C57BL/6 genotype at char2 does not increase the likelihood of survival. One can envisage a baseline response to infection that may be actively disrupted by the C3H/He genotype yet not be enhanced by the C57BL/6 genotype.

In summary, the generation and analysis of a panel of recombinant char2 congenic animals have demonstrated that char2 independently influences the outcome of malarial infection in mice. It has also resulted in the refinement of the map position of the locus and has provided us with the tools and confidence to proceed with the positional cloning of the gene. In so doing, we will greatly enhance our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the host response to malarial infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Welcome Trust and The National Health And Medical Research Council. R.A.B. was supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award.

Editor: R. N. Moore

REFERENCES

- 1.Burt, R. A., T. M. Baldwin, V. M. Marshall, and S. J. Foote. 1999. Temporal expression of an H2-linked locus in host response to mouse malaria. Immunogenetics 50:278-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foote, S. J., R. A. Burt, T. M. Baldwin, A. Presente, A. W. Roberts, Y. L. Laural, A. M. Lew, and V. M. Marshall. 1997. Mouse loci for malaria-induced mortality and the control of parasitaemia. Nat. Genet. 17:380-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fortin, A., A. Belouchi, M. F. Tam, L. Cardon, E. Skamene, M. M. Stevenson, and P. Gros. 1997. Genetic control of blood parasitaemia in mouse malaria maps to chromosome 8. Nat. Genet. 17:382-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lander, E. S., and D. Botstein. 1989. Mapping Mendelian factors underlying quantitative traits using RFLP linkage maps. Genetics 121:185-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markel, P., P. Shu, C. Ebeling, G. A. Carlson, D. L. Nagle, J. S. Smutko, and K. J. Moore. 1997. Theoretical and empirical issues for marker-assisted breeding of congenic mouse strains. Nat. Genet. 17:280-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snell, G. D. 1958. Histocompatibility genes of the mouse. I. Demonstration of weak histocompatibility differences by immunization and controlled tumor dosage. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 20:787-824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wakeland, E., L. Morel, K. Achey, M. Yui, and J. Longmate. 1997. Speed congenics: a classic technique in the fast lane (relatively speaking). Immunol. Today 18:472-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng, Z. 1994. Precision mapping of quantitative trait loci. Genetics 136:1457-1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]