Abstract

Oral immunization of mice with a Salmonella vaccine expressing colonization factor antigen I (CFA/I) from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli results in the rapid onset of interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-5 production, which explains the observed elevations in mucosal immunoglobulin A (IgA) and serum IgG1 antibodies. In contrast, oral immunization with the Salmonella vector does not result in the production of Th2-type cytokines. To begin to assess why such differences exist between the two strains, it should be noted that in vitro infection of RAW 264.7 macrophages resulted in the absence of nitric oxide (NO) production in cells infected with the Salmonella-CFA/I vaccine. This observation suggests differential proinflammatory cytokine production by these isogenic Salmonella strains. Upon measurement of proinflammatory cytokines, minimal to no tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL-1α, IL-1β, or IL-6 was produced by Salmonella-CFA/I-infected RAW 264.7 or peritoneal macrophages, but production was greatly induced in Salmonella vector-infected macrophages. Only minute levels of IL-12 p70 were induced by Salmonella vector-infected macrophages, and none was induced by Salmonella-CFA/I-infected macrophages. The absence of IL-12 was not due to overt increases in production of either IL-12 p40 or IL-10. CFU measurements taken at 8 h postinfection showed no differences in colonization in RAW 264.7 cells infected with either Salmonella construct, but there were differences in peritoneal macrophages. However, after 24 h, the Salmonella vector strain colonized to a greater extent in RAW 264.7 cells than in peritoneal macrophages. Infection of RAW 264.7 cells or peritoneal macrophages with either Salmonella construct showed no difference in macrophage viabilities. This evidence shows that the expression of CFA/I fimbriae alters how macrophages recognize or process salmonellae and prevents the rapid onset of proinflammatory cytokines which is typical during Salmonella infections.

Salmonella has been successfully adapted for live-vector vaccine delivery in experimental animals (12, 23, 36) and poultry (13) and is particularly effective for immunization against mucosal pathogens, especially those requiring Th1-cell-dependent immunity (37, 45-47). By convention, Th1-cell-dependent immunity is required to clear Salmonella infection (21, 27, 42), yet there are a few studies in which this vaccine vector has been shown to induce Th2-type immunity against the passenger vaccine (3, 22, 33). This may be due in large part to the way the vaccine antigen is presented by this vaccine vector. In fact, in a recent study, we have shown that the extracellular secretion by Salmonella of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli fimbrial adhesin, colonization factor antigen I (CFA/I), promotes the rapid onset of mucosal immunoglobulin A (IgA) and serum IgG1 anti-CFA/I antibodies supported by Th2-type cytokines interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-5 with minimal to no gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production (33). However, an incremental induction of Th1-cell (IFN-γ)-dependent responses, which is needed to resolve this Salmonella infection, has been observed. CFA/I expression in Salmonella results in the stimulation of a biphasic Th-cell response consisting of a dominant early Th2-type response followed by a corresponding induction of Th1 cells that eventually dominates the antivaccine response. Such biphasic Th-cell responses are unprecedented with Salmonella vaccine vectors. While it remains unclear whether the mode of vaccine presentation or the vaccine itself alters the initial anti-Salmonella responses, such an observation suggests that the initial recognition of the fimbriated salmonellae must somehow alter the conventional mechanisms for resolving Salmonella infections. Importantly, it also suggests that an alternative mechanism might be used to control this intracellular pathogen when Th2 cells or anti-inflammatory responses are present.

Past studies have shown that Salmonella stimulates the rapid onset of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) following in vivo infection (15, 26, 39) or in vitro infection (1, 11) of macrophages. TNF-α together with IFN-γ activates macrophages for the enhanced killing of Salmonella (31, 35). Consequently, anti-TNF-α treatment exacerbates salmonellosis (28), resulting in diminished nitric oxide (NO) production (1). TNF-α has also been shown to be linked to Nramp1 gene expression (1, 7). Resistance to infection by intracellular pathogens has been shown to be linked to the expression of the Nramp1 gene (6, 18-20, 43), which encodes an ion transporter molecule (17). The mode of action is believed to be a pH-dependent extrusion of Mn2+ which removes divalent cations from the phagosomal space (24). Nramp1 gene expression has also been linked to enhanced NO production (1, 5). Thus, the expression of Nramp1 provides a mechanism of resistance to intracellular pathogen infection by limiting macrophage colonization.

Our results show that infection of macrophages with Salmonella-CFA/I results in an absence of NO production and minimal to no proinflammatory cytokine production, as compared to that resulting from infection of macrophages with the isogenic Salmonella vector. This reduction in proinflammatory cytokine production may help explain why elevated Th2-cell responses dominate the early events following in vivo infection. This evidence suggests that the presence of CFA/I fimbriae alters the way in which the Salmonella vaccine vector is recognized and processed by the innate immune system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains.

The S. enterica serovar Typhimurium-CFA/I vector vaccine strain, H696, and its isogenic control which lacks the CFA/I operon, H647 (Salmonella vector), were used in these studies. Functional CFA/I fimbrial expression was maintained by a plasmid with a functional asd gene, which complements the lethal chromosomalΔasd mutation and stabilizes CFA/I expression in the absence of antibiotic selection (44). The isogenic control strain H647 was also maintained using the same complementation (44). Both strains were grown to log phase in Luria broth for 15 h to minimize Salmonella cell death.

Mice and peritoneal macrophage isolation.

BALB/c mice (Frederick Cancer Research Facility, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, Md.), 6 to 12 weeks of age, were maintained in horizontal laminar-flow cabinets; sterile food and water were provided ad libitum. All animal care and procedures were done in accordance with institutional policies for animal health and well-being.

The BALB/c mice were given a single interperitoneal injection of 1.0 ml of expired thioglycolate medium (Difco, Detroit, Mich.), and 3 days later, the peritoneum of each mouse was washed with RPMI 1640 (Gibco BRL-Life Technologies [Life Technologies], Grand Island, N.Y.) containing 2% fetal calf serum (Life Technologies) without antibiotics. Peritoneal cells were washed twice in the same medium without antibiotics.

Macrophage infection cultures.

Both RAW 264.7 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) and peritoneal macrophages were evaluated for proinflammatory cytokine production subsequent to infection with Salmonella-CFA/I or its isogenic strain, H647. RAW 264.7 and peritoneal macrophages were added at 1.25 × 106 cells/well in complete medium (33) without antibiotics and were allowed to adhere to plastic in 24-well microtiter dishes (BD Labware, Franklin Lakes, N.J.) for 3 h at 37°C. The wells were washed to remove nonadherent cells. The nonadherent cells were collected and counted to determine the numbers of cells that remained plastic adherent. To confirm that the plastic-adherent cells were peritoneal macrophages, immunofluorescent staining of the cells was performed using the monoclonal antibody (MAb), F4/80 (Serotec, Inc., Raleigh, N.C.). More than 95% of the adherent cells were F4/80 positive. After overnight culture, cells were infected at various salmonella-to-macrophage ratios (0.01:1 to 100:1) for 1 h at 37°C. The wells were washed twice with complete medium without antibiotics and then incubated with 50 μg of gentamicin (Life Technologies) per ml for 30 min at 37°C. After the cells were washed twice as described above, fresh complete medium without antibiotics (1.0 ml/well) was added and the cells were incubated for an additional 8 or 24 h. Supernatants were collected and frozen until analysis by cytokine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

NO production assay.

Supernatants from Salmonella vector-infected RAW 264.7 and peritoneal macrophages were collected after 24 h and measured for the accumulation of nitrite, the oxidized product of NO, as previously described (32). All detection chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). Aliquots of 50 μl of cell culture supernatant were reacted with equal volumes of Griess reagent (1% sulfanilamide, 0.1% naphthylenediamine dihydrochloride, 2.5% H3PO4) at room temperature (RT) for 10 min. Sodium nitrite was used to generate a standard curve for NO2− production, and peak absorbance was measured at 550 nm with a Thermomax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, Calif.). Cell-free medium contained <0.5 μM NO2−. To assess the role of TNF-α in NO production, a 20-μg/ml concentration of rat IgG1 anti-mouse TNF-α MAb (clone G281-2626; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.) was added to some cultures after infection with Salmonella vector (strain H647). The rat IgG1 anti-mouse IFN-γ (R4-6A2; B-D PharMingen) was used as an isotype-matched control antibody.

Cytokine ELISAs.

Cytokine secretion by infected macrophages was detected using the cytokine-specific ELISAs for IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12 p70, and IL-12 p40. Similar ELISA protocols were adapted for each cytokine (14). The following primary (coating) and secondary antibodies (Abs), respectively, were used in 50-μl volumes: for IL-1α, 3.0 μg of hamster anti-mouse IL-1α MAb (clone ALF-161; BD Pharmingen) per ml and 2.5 μg of goat anti-mouse IL-1α (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) per ml; for IL-1β, 4.0 μg of rat anti-mouse IL-1β (clone 30311.11; R&D Systems) per ml and 0.2 μg of biotinylated goat anti-IL-1β (R&D Systems) per ml; for TNF-α, 10 μg of rat anti-mouse TNF-α (clone G281-2626; BD Pharmingen) per ml and 0.25 μg of biotinylated rat anti-mouse TNF-α (clone MP6-XT3; BD Pharmingen) per ml; for IL-6, 2.0 μg of rat anti-mouse IL-6 (clone MP5-20F3; BD Pharmingen) per ml and 0.5μg of biotinylated rat anti-IL-6 MAb (clone MP5-32C11; BD Pharmingen) per ml; for IL-10, 2.0 μg of rat anti-mouse IL-10 (clone JES5-2A5; BD Pharmingen) per ml and 0.3 μg of biotinylated rat anti-IL-10 MAb (clone SXC-1; BD Pharmingen) per ml; for IL-12 p70, 2.0 μg of rat anti-mouse IL-12 p70 (clone R2-9A5; American Type Culture Collection) per ml; and 1.0 μg of biotinylated rat anti-mouse IL-12 p40 (clone C17.8; BD Pharmingen) per ml; and for IL-12 p40, 6.0 μg of rat anti-mouse IL-12p40 (clone C15.6; BD Pharmingen) per ml and 1.0 μg of biotinylated rat anti-mouse IL-12 p40 per ml. Incubation with secondary Abs varied between ELISAs: for IL-1α and IL-1β, it was 2 h at 37°C; for TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-12 p40, it was 90 min at RT; for IL-10 and IL-12 p70, it was 45 min at RT. For IL-1α, a 1:3,000 dilution of tertiary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-donkey anti-goat IgG Ab (Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corp., Westbury, N.Y.) was used. For IL-1β and TNF-α, a 1:1,000 dilution of HRP-goat anti-biotin Ab (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.) was used and developed with the substrate 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline 6-sulfonic acid)diammonium (Moss, Inc., Pasadena, Calif.). Absorbances were read at 415 nm on a Kinetics Reader model EL312 (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, Vt.). For IL-6, IL-10, IL-12 p70, and IL-12 p40, a 1:2,000 dilution of alkaline phosphatase-goat anti-biotin (Vector Laboratories) was used, developed with the fluorescent substrate 4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate dicyclohexylammonium salt (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.), and read with a Bio-Tek Instruments FL600 microtiter plate reader. To determine the amount of cytokine present in the test samples, various dilutions of recombinant murine cytokines, IL-1α and IL-1β (PeproTech, Inc., Rocky Hill, N.J.), and IL-6, IL-10, IL-12 p70, IL-12 p40, and TNF-α (R&D Systems) were used to establish standard curves from which values for the test samples could be extrapolated.

Serovar Typhimurium colonization.

To determine the extent of Salmonella colonization, infected RAW 264.7 and peritoneal macrophages were lysed after gentamicin treatment (t = 0), after 8 h, or after 24 h. Plastic-adherent infected macrophages were lysed with 1.0 ml of sterile distilled water after repeated pipetting. Serial logarithmic dilutions were made and plated onto Luria broth agarose for overnight incubation at 37°C. CFU enumerations were performed, and salmonella-to-macrophage infection ratios were determined.

Macrophage viability.

To assess the viability of RAW 264.7 and peritoneal macrophages after infection with Salmonella vaccine vectors, macrophages (105/well) were seeded in 96-well microtiter dishes (BD Labware) and infected with of Salmonella-CFA/I or the Salmonella vector control strain at various ratios as described above. At 24 h after infection, the wells were washed with medium without antibiotics, and an assessment of dead macrophages was conducted subsequent to the addition of 2.0 μM ethidium homodimer-1 (Molecular Probes) in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline-0.001% sodium azide. Following a 20-min incubation at RT in the dark, the extent of fluorescence was measured with a Bio-Tek FL600 fluorescence plate reader at an excitation wavelength of 530 nm and an emission wavelength of 645 nm. The absence of fluorescence for uninfected macrophages was set as representing 100% viability, and the maximum fluorescence for methanol-lysed macrophages was set as representing 0% viability.

Statistical analysis.

The Student t test was used to evaluate differences between variations in cytokine production levels. A paired t test was performed to discern differences in the extent of colonization of macrophages.

RESULTS

Absence of NO following infection of RAW 264.7 cells with Salmonella-CFA/I.

Results from previous studies have shown that the expression of fimbriae from CFA/I-positive enterotoxigenic E. coli by an attenuated Salmonella vector results in the rapid onset of elevated secretory IgA antibodies supported by Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-5 (33). Such Th2-type cytokines were not induced by the isogenic control strain. These findings suggest that the expression of the fimbriae may alter how the host recognizes fimbriated salmonellae and perhaps that the ways the macrophages recognize them may differ. RAW 264.7 cells were infected with various bacterium-to-macrophage ratios, either with the Salmonella vector control strain H647 or the fimbriated Salmonella CFA/I vector strain H696. After 24 h, culture supernatants were collected and nitrite accumulation was detected with Griess reagent (32). Surprisingly, minimal to no NO production was observed for cells infected with the Salmonella-CFA/I vaccine strain, whereas the isogenic Salmonella control strain H647 stimulated NO production, even at a ratio as low as 1 bacterium to 80 RAW 264.7 cells (Table 1). Treatment of RAW 264.7 cells with a monoclonal anti-TNF-α antibody, but not an isotype-matched rat anti-mouse IFN-γ MAb, inhibited ∼43% of the observed NO production induced by the H647 strain (Table 1). This evidence suggested differential proinflammatory cytokine production by these isogenic Salmonella strains.

TABLE 1.

Infection of RAW 264.7 macrophages with an attenuated Salmonella vector, but not with a Salmonella-CFA/I vaccine strain, induces NO

| Infection ratio (salmonella:macrophage) | Nitrite concn (μm) (mean ± SD) for macrophages infected witha:

|

P value (H647 vs. H696) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salmonella vector | Salmonella-CFA/I | ||

| No infection | NDb | NDb | |

| 1:80 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | NDb | 0.015 |

| 1:40 | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 0.009 |

| 1:20 | 6.4 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 0.023 |

| 1:10 | 34.6 ± 2.0 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 0.002 |

| 1:1 | 74.5 ± 8.4 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 0.007 |

| 10:1 | 155.0 ± 11.0 | 8.2 ± 3.8 | 0.003 |

| 10:1 + anti-TNF-α | 88.0 ± 6.9 | 0.007c | |

| 10:1 + anti-IFN-γ | 145.0 ± 15.1 | NSd | |

RAW 264.7 macrophages were infected with Salmonella vector (strain H647) or Salmonella-CFA/I vaccine (strain H696), and culture supernatants were collected after 24 h.

ND, not detected.

Significant reduction in NO levels by RAW 264.7 cells treated with 20 μg of anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibody per ml.

NS, not significant.

Infection of RAW 264.7 and peritoneal macrophages with Salmonella-CFA/I results in diminished proinflammatory cytokine production.

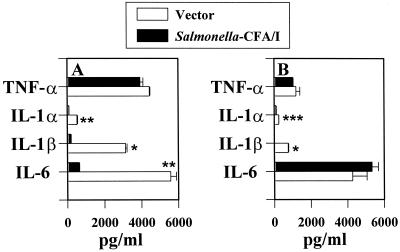

We hypothesized that the presence of CFA/I fimbriae may prevent the proinflammatory cascade that is typically observed with Salmonella infections. To evaluate what proinflammatory cytokines were induced subsequent to infection, RAW 264.7 macrophages were infected at low bacterium-to-macrophage ratios, since our in vivo analyses revealed that even a relatively small number of bacteria of both strains infect host Peyer's patches (data not shown). Consequently, ratios lower than 1 bacterium to 1 macrophage were encountered after macrophages were infected for 1 h and incubated for 30 min with gentamicin. As anticipated, infecting macrophages with the Salmonella vector in ratios as low as 1 bacterium to 100 macrophages induced rapid stimulation of TNF-α, as measured 8 h following gentamicin treatment (Fig. 1A). In contrast, infection with a similar ratio of Salmonella-CFA/I bacteria to macrophages resulted in no detectable stimulation of TNF-α. Detectable levels of TNF-α were observed only at a bacterium-to-macrophage ratio of greater than 0.6:1 (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1A). Measurements of the levels of other proinflammatory cytokines showed a similar inability of Salmonella-CFA/I to stimulate their production in RAW 264.7 macrophages, as evidenced by the absence of IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6 production in these cells, in contrast to cells infected with the Salmonella vector (Fig. 1B to D).

FIG. 1.

The expression of CFA/I fimbriae by an attenuated Salmonella construct prevents the production of proinflammatory cytokines by infected RAW 264.7 macrophages. RAW 264.7 macrophages were infected with the Salmonella-CFA/I strain, H696, or its isogenic vector control, H647, for 1 h at varyious Salmonella-to-macrophage ratios between 0.01:1 and 1.0:1 and then treated for 30 min with gentamicin. After being washed, the macrophages were cultured for an additional 8 h, and supernatants were harvested for TNF-α (A), IL-6 (B), IL-1α (C), and IL-1β (D) ELISAs. Macrophages infected with Salmonella-CFA/I showed minimal to no cytokine generation compared to macrophages similarly infected with its isogenic Salmonella vector strain. Data are the means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) of values from four experiments. Statistical differences between cytokines induced by infection with the Salmonella vector versus the Salmonella-CFA/I strain are represented by ∗ (P ≤ 0.001) and ∗∗ (P ≤ 0.013).

To show whether the original findings observed with the RAW 264.7 cells were limited to this specific cell line or whether normal macrophages were also unable to produce proinflammatory cytokines, thioglycolate-induced peritoneal macrophages were isolated from peritoneal washes of BALB/c mice. TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6 were assayed in culture supernatants 8 h after infection of peritoneal macrophages with either the Salmonella-CFA/I vaccine strain or its isogenic Salmonella control. As with the RAW 264.7 cells, peritoneal macrophages were infected with a bacterium-to-macrophage ratio lower than 1. There was no production of TNF-α and IL-1β, whereas IL-1α and IL-6 levels were 10-fold and 50- to 60-fold lower, respectively, than in peritoneal macrophages infected with the Salmonella vector (Fig. 2). Thus, this evidence shows that the infection of normal macrophages is altered when salmonellae are fimbriated with CFA/I.

FIG. 2.

The expression of CFA/I fimbriae by an attenuated Salmonella construct prevents the production of proinflammatory cytokines by infected peritoneal macrophages. Peritoneal macrophages were infected with the Salmonella-CFA/I strain, H696, or its isogenic vector control, H647, as described for RAW 264.7 cells in the legend to Fig. 1. Macrophages were cultured for 8 h, and supernatants were harvested for TNF-α (A), IL-6 (B), IL-1α (C), and IL-1β (D) ELISAs. Macrophages infected with Salmonella-CFA/I showed minimal to no cytokine generation compared to macrophages similarly infected with its isogenic Salmonella vector strain. Data are the means ± SEM of values from four experiments. The statistical difference between cytokines induced by infection with the Salmonella vector versus the Salmonella-CFA/I strain is represented by ∗ (P ≤ 0.001).

IL-1 is not induced in macrophages infected with a high dose of Salmonella-CFA/I.

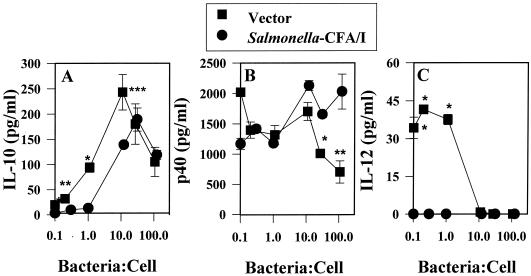

Experiments were also conducted to assess proinflammatory cytokine production at higher bacterium-to-macrophage ratios. As previously indicated, Salmonella-CFA/I did not induce proinflammatory cytokines at infection ratios of less than 1. At an infection ratio higher than 1 for RAW 264.7 macrophages, Salmonella-CFA/I did induce increases in TNF-α but not in IL-α (P < 0.004), IL-1β (P ≤ 0.001), or IL-6 (P < 0.002), when compared to levels in Salmonella vector-infected cells. In three experiments, TNF-α levels peaked at a 10:1 bacterium-to-macrophage ratio for RAW 264.7 cells infected with either Salmonella-CFA/I or the Salmonella vector (Fig. 3A). At higher infection ratios, macrophage survival negatively impacted proinflammatory cytokine production, especially at infection ratios of >10:1. Similar experiments were also conducted for peritoneal macrophages. Again, at an infection ratio of 10:1, no significant differences were observed in TNF-α production and IL-1α (P ≤ 0.03) and IL-1β production (P ≤ 0.001) remained significantly lower than in Salmonella vector-infected macrophages (Fig. 3B). Unlike in infected RAW 264.7 cells, there were no significant differences in IL-6 production levels between peritoneal macrophages infected with either Salmonella strain. As with the RAW 264.7 cells, at infection ratios of >10:1, peritoneal macrophage survival negatively impacted proinflammatory cytokine production.

FIG. 3.

Infection of macrophages with high doses of Salmonella-CFA/I can still result in diminished production of proinflammatory cytokines. RAW 264.7 (A) or peritoneal macrophages (B) were infected with the Salmonella-CFA/I strain, H696, or its isogenic vector control, H647, for 1 h at a Salmonella-to-macrophage ratio of 10:1 and then treated for 30 min with gentamicin. After being washed, the macrophages were cultured for an additional 8 h, and supernatants were harvested for TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6 ELISAs. In both experiments, macrophages infected with Salmonella-CFA/I showed equivalent induction of TNF-α but minimal to no IL-1 production compared to that of macrophages similarly infected with the isogenic Salmonella vector. IL-6 production was also substantially reduced in Salmonella-CFA/I-infected RAW 264.7 cells compared to that in peritoneal macrophages. Data are the means ± standard deviations and represent the results of three experiments. The statistical differences between cytokines induced by infection with the Salmonella vector versus the Salmonella-CFA/I strain are represented by ∗ (P ≤ 0.001),∗∗ (P ≤ 0.004), and ∗∗∗ (P = 0.03).

Infection of RAW 264.7 macrophages with Salmonella-CFA/I fails to stimulate IL-12, and lower levels of IL-10 are induced.

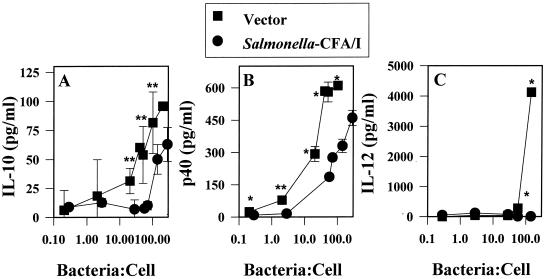

It is well established that Salmonella rapidly induces proinflammatory cytokines during the early phase (40) of infection, as measured by both in vitro (15, 26, 39) and in vivo assays (1, 11). Subsequent to the production of the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6, a second wave of cytokines was stimulated (4). This second wave of cytokines included IL-10 and IL-12. Typically, intracellular pathogens stimulate IL-12 or the host requires IL-12 for protection (8, 14, 38, 41, 48). In our in vivo studies, a delay in IgG2a and IFN-γ production subsequent to infection of mice with Salmonella-CFA/I was observed (33), suggesting that the limited stimulation of proinflammatory cytokines subsequent to the infection of macrophages may also limit IL-12 production. To test this hypothesis, RAW 264.7 cells were infected at varyious ratios between 0.1 and 100 Salmonella bacteria per macrophage; the results showed that indeed Salmonella-CFA/I could not stimulate IL-12 (Fig. 4C), whereas the Salmonella vector control could. However, it was surprising to learn that IL-12 was induced only at a high infection ratio with the Salmonella vector and that it was not evident at the lower bacterium-to-macrophage ratios. Likewise, IL-10 was generated only at the higher bacterium-to-macrophage ratios for both Salmonella strains, but induction of IL-10 for Salmonella-CFA/I-infected macrophages was delayed compared to that of IL-10 by the Salmonella vector (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

IL-12 is not stimulated following the infection of RAW 264.7 macrophages with Salmonella-CFA/I. RAW 264.7 cells were infected as described in the legend to Fig. 1 but at Salmonella-to-macrophage ratios between 0.1:1 and 100:1. Infected cells were cultured for 24 h, and supernatants were analyzed for the presence of IL-10 (A), IL-12 p40 (B), and IL-12 p70 (C) by ELISA. Data are the means± SEM of values from four experiments. Statistical differences between cytokines induced by infection with the Salmonella vector versus the Salmonella-CFA/I strain are represented by ∗ (P < 0.001) and ∗∗ (P ≤ 0.009).

Infection of peritoneal macrophages with Salmonella-CFA/I also fails to stimulate a second wave of proinflammatory cytokines.

To assess whether IL-12 is also inhibited after 24 h of infection, thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal macrophages were infected at varyious ratios between 0.1 and 100 Salmonella bacteria per macrophage. As with the RAW 264.7 macrophages, Salmonella-CFA/I could not induce IL-12 in the peritoneal macrophages, but the Salmonella vector could (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, the Salmonella vector could induce IL-12 more readily in peritoneal macrophages than in RAW 264.7 cells, as evidenced by the much lower infection ratios required to induce IL-12. One possible explanation for the absence of an IL-12 response subsequent to infection with Salmonella-CFA/I is an increased level of IL-12 p40 homodimer, an IL-12 inhibitor. However, when macrophages were infected by either Salmonella strain at the infection ratios at which IL-12 was induced by the Salmonella vector, there was no statistical difference in IL-12 p40 levels (Fig. 5B). Alternatively, the lack of IL-12 may be due to increased levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10, but this was not apparent (Fig. 5A). As with the RAW 264.7 cells, the IL-10 response was delayed for Salmonella-CFA/I-infected peritoneal macrophages and was greatest for Salmonella vector-infected macrophages.

FIG. 5.

IL-12 is not stimulated following the infection of peritoneal macrophages with Salmonella-CFA/I. Macrophages were infected as described in the legend to Fig. 1 but with Salmonella-to-macrophage ratios between 0.1:1 and 100:1. Infected cells were cultured for 24 h, and supernatants were analyzed for the presence of IL-10 (A), IL-12 p40 (B), and IL-12 p70 (C) by ELISA. Data are the means ± SEM of values from four experiments. Statistical differences are represented by∗ (P ≤ 0.001), ∗∗ (P ≤ 0.016), and ∗∗∗ (P < 0.025).

Absence of Proinflammatory cytokines is not attributed to differences in Salmonella infection.

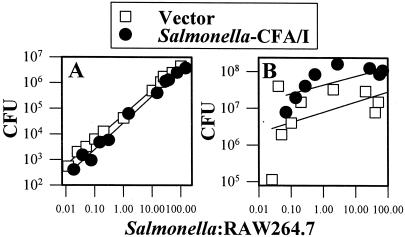

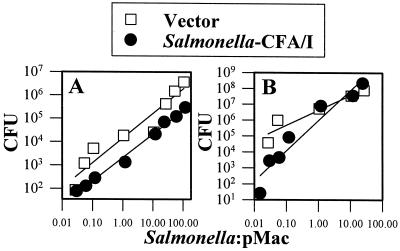

One plausible explanation for the absence of the induction of proinflammatory cytokine production by Salmonella-CFA/I may be that fimbrial expression alters its ability to infect macrophages. CFU levels were assessed following the infection of RAW 264.7 cells with Salmonella-CFA/I or the Salmonella vector after 8 or 24 h (Fig. 6). There were no significant differences in CFU levels 8 h after the infection of RAW 264.7 cells with either the Salmonella-CFA/I vaccine or the Salmonella vector (Fig. 6A). However, 24 h after infection, the Salmonella-CFA/I CFU levels were significantly higher (Fig. 6B), possibly because of the failure to produce proinflammatory cytokines. Thus, there was no difference in growth in RAW 264.7 cells 8 h postinfection, and the deficit in proinflammatory cytokine production induced by Salmonella-CFA/I may have allowed this strain to exceed the CFU levels of Salmonella vector after 24 h.

FIG. 6.

Salmonella-CFA/I shows increased colonization at 24 h after infection (B) but not at 8 h after infection (A) of RAW 264.7 macrophages compared to colonization by Salmonella vector. Macrophages were infected as previously described, and CFU were enumerated. No significant differences in colonization were observed after 8 h, but after 24 h, Salmonella-CFA/I CFU levels were higher than those in Salmonella-infected macrophages (P ≤ 0.001). Data represent the means of values from three experiments.

An examination of peritoneal macrophages at 8 h postinfection with Salmonella-CFA/I or the Salmonella vector showed that both Salmonella vaccines were efficient in colonization, but the Salmonella vector showed significantly greater colonization (Fig. 7A). In contrast, by 24 h postinfection, there were no significant differences in the levels of colonization by the two Salmonella vaccines (Fig. 7B). These studies show that these two isogenic Salmonella strains replicate differently in RAW 264.7 and peritoneal macrophages.

FIG. 7.

Salmonella vector shows increased colonization at 8 h after infection (A) but not at 24 h after infection (B) of peritoneal macrophages (pMac) compared to colonization by Salmonella-CFA/I vector. Macrophages were infected as previously described, and CFU counts were conducted. Significant differences in colonization were observed only at 8 h (P = 0.008) but not at 24 h after infection with Salmonella vector or Salmonella-CFA/I. Data represent the means of values for three experiments.

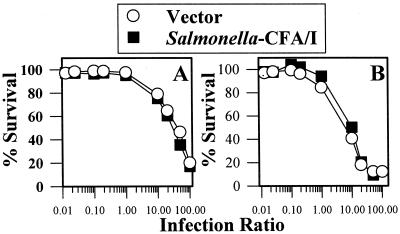

Absence of selective killing of macrophages by Salmonella-CFA/I or Salmonella vector.

The paucity in proinflammatory cytokine production subsequent to infection with Salmonella-CFA/I may be attributed to increased macrophage cell death, since protective proinflammatory cytokines are not induced. Further, it is well established that infection with Salmonella can result in host cell death (2, 10, 30). To assess macrophage survival, RAW 264.7 and peritoneal macrophages were infected with Salmonella-CFA/I and Salmonella vector for 24 h, and cell death was measured by the extent of ethidium homodimer-1 uptake (Fig. 8). There were no significant differences in the attrition of RAW 264.7 or peritoneal macrophages infected with either Salmonella-CFA/I or the Salmonella vector. Thus, the expression of CFA/I fimbriae does not enhance macrophage death and must alter macrophage processing or the course of intracellular infection by the Salmonella bacteria.

FIG. 8.

Variations in observed cytokine responses by macrophages infected with either Salmonella-CFA/I or Salmonella vector are not due to differences in macrophage viability. RAW 264.7 (A) and peritoneal macrophages (B) were infected at various Salmonella-to-cell ratios as previously described, and cell viabilities were measured 24 h later by determining the extent of ethidium bromide uptake. Data represent the means of values for three experiments.

DISCUSSION

One particular characteristic of infection by the Salmonella-CFA/I strain is the stimulation of a biphasic Th-cell response in both BALB/c (33) and C57BL/6 (34) mice. This includes the rapid onset of mucosal IgA and serum IgG1 responses during the first week postinfection. However, it remains unclear how such events are accomplished by this Salmonella vaccine vector, which by convention should stimulate proinflammatory and Th1-cell-dependent responses (21, 27, 42). One plausible mechanism for the early induction of Th2-cell responses may be the mimicry of soluble protein immunization by the surface expression of CFA/I fimbriae in the Salmonella vector. Alternatively, the CFA/I fimbriae may interfere with the way in which the host recognizes the Salmonella vaccine vector.

To assess this latter possibility, in vitro macrophage infection assays were performed. Low infection ratios were used, since there is a lack of in vivo evidence to suggest that, during the infection stage in vivo, the Salmonella vectors infect tissue macrophages at bacterium-to-macrophage ratios above 1 and, for that matter, at 10:1 or 100:1, as commonly tested by vitro assays. In our studies, infection ratios above 1 adversely impacted macrophage survival. Thus, to quantify cytokine responses during the early phase (8-h time point) of infection, the majority of the studies were conducted at infection ratios of less than 1. Surprisingly, Salmonella-CFA/I attenuated much of the early proinflammatory cytokine responses by RAW 264.7 or peritoneal macrophages. Macrophages infected with the isogenic Salmonella vector stimulated TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6 at infection ratios as low as 0.001:1. Such exquisite susceptibility to such low doses of Salmonella suggests that infection at ratios of less than 1 are sufficient to assess proinflammatory cytokine induction without concern for host cell death.

When additional tests were conducted to assess whether higher infection ratios would induce increases in proinflammatory production, TNF-α levels peaked at an infection ratio of approximately 10:1 for both RAW 264.7 and peritoneal macrophages. Furthermore, at this higher infection ratio, Salmonella-CFA/I was as effective in stimulating TNF-α as the Salmonella vector was. Such increased stimulation of TNF-α may be attributed simply to the increased numbers of Salmonella-CFA/I bacteria or to the fact that because of these increased numbers, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) may be compounding the effect. It is important to note that infection with the Salmonella vector at ratios as low as 0.001:1 stimulated increases in proinflammatory cytokine production. Thus, it is not expected that these lower infection ratios are due to the contribution of LPS, since the LPS contents of these two isogenic constructs are equivalent. Rather, it may be that the effect of LPS is more significant at the higher infection ratios or when the Salmonella burden is increased and that, at the lower infection ratios, the bacteria themselves are responsible for stimulating proinflammatory cytokines.

For the short-term infection, TNF-α levels varied at infection ratios higher than 10 (data not shown). There was clearly more macrophage cell death at these higher infection ratios, which would account for this variability. As evidenced for the peritoneal macrophages, a 50% survival rate was seen at an infection ratio of approximately 10:1. There were no significant differences in macrophage survival rates for both RAW 264.7 and peritoneal macrophages when infected with either construct at any of the tested ratios between 0.01:1 and 100:1. These data support the notion that the expression of the CFA/I fimbriae alters macrophage recognition and does not preferentially kill macrophages.

Evaluation of CFU levels at 8 h postinfection revealed no significant differences in colonization of RAW 264.7 macrophages by either Salmonella construct, but differences in proinflammatory cytokine production were evident. Yet, after 24 h, colonization by Salmonella-CFA/I exceeded that of its isogenic Salmonella control strain, suggesting that the diminution in proinflammatory cytokines and NO allowed for these increases in CFU. In contrast, colonization of peritoneal macrophages by Salmonella-CFA/I was significantly less at 8 h, but not at 24 h, postinfection. Yet the reductions in proinflammatory cytokine production imitated what was observed with the infection of RAW 264.7 macrophages.

Examination of other proinflammatory cytokines, produced when macrophages were infected at a 10:1 ratio with Salmonella-CFA/I, showed that cytokine levels were dependent upon the macrophage tested. For RAW 264.7 macrophages, Salmonella-CFA/I and the Salmonella vector were equally effective in stimulating only TNF-α, but IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels remained reduced in Salmonella-CFA/I-infected macrophages. For peritoneal macrophages, as with the RAW 264.7 cells, Salmonella-CFA/I and the Salmonella vector were equally effective in stimulating only TNF-α, while IL-1α and IL-1β levels remained reduced in Salmonella-CFA/I-infected macrophages. IL-6 levels were also induced equally by both Salmonella constructs. Thus, these data suggest that the expression of the CFA/I fimbriae delays the production of inflammatory cytokines which may contribute to or allow for Th2-cell development early in the in vivo infection with Salmonella-CFA/I.

One manifestion of Salmonella infection of macrophages is the onset of NO production, which contributes to the elimination of Salmonella (1, 31, 35). NO was induced only by RAW 264.7 cells infected with the Salmonella vector H647 strain and not by those infected with the fimbriated H696 strain. This provided further evidence that the expression of the CFA/I fimbriae suppresses or fails to stimulate proinflammatory cytokines subsequent to infection. At a high infection ratio (10:1), only TNF-α (not IL-1α, IL-1β, or IL-6) was stimulated, and NO levels were 20-fold less than those produced upon infection with the Salmonella vector.

Proinflammatory cytokines are generally produced in a cascade fashion subsequent to bacterial infection (40) and are rapidly cleared. TNF-α is generally an indicator of the early onset of disease, and late in the infection, TNF-α and other proinflammatory cytokines stimulate IL-12 and IL-10 (4). IL-12 is believed to be induced subsequent to intracellular infection (8, 38, 41, 48) and has been shown to be important to resolve Salmonella infections (14, 25, 29). Thus, IL-12 and IL-10 responses were measured to indicate second-wave responses. Interestingly, minimal to no IL-12 was measured when macrophages were infected with the control Salmonella vector. This is consistent with previously shown data indicating that Salmonella is a poor inducer of IL-12 (9, 14). In fact, Salmonella fails to stimulate the IL-12 high-affinity receptor in macrophages (16). The source and amounts of IL-12 during in vivo infections with Salmonella remain to be determined, since it has been shown that in the absence of IL-12, mice succumb more rapidly to Salmonella (14). No IL-12 was generated when macrophages were infected with Salmonella-CFA/I. This last observation is consistent with the notion that proinflammatory cytokines are necessary to stimulate IL-12 (4), since the proinflammatory cytokine responses were attenuated subsequent to infection with Salmonella-CFA/I. Furthermore, we failed to detect IL-18 production by either RAW 264.7 or peritoneal macrophages infected with either Salmonella strain (data not shown). This is consistent with what was previously reported for optimal stimulation of IL-18 (14).

To assess why IL-12 was not induced subsequent to infection with Salmonella-CFA/I, IL-12 p40 and IL-10 were measured, since these cytokines can potentially inhibit IL-12 production. Measurements of IL-12 p40 showed no preferential increase due to Salmonella-CFA/I and, in fact, were lower in RAW 264.7 macrophages that were infected with the Salmonella vector. For peritoneal macrophages, no significant differences in IL-12 p40 levels were noted in cells infected by either Salmonella strain. For both RAW 264.7 and peritoneal macrophages, cells infected with Salmonella-CFA/I showed consistently less IL-10 production than did cells infected with the Salmonella vector. These combined results show that the absence of proinflammatory cytokines following infection with Salmonella-CFA/I was not attributed to preferential increases in IL-12 p40 or IL-10. Measurements after 24 h were complicated by increased Salmonella release, which resulted in decreased macrophage viability. Collectively, these studies suggest that proinflammatory cytokine production is delayed subsequent to oral immunization with Salmonella-CFA/I, allowing for the rapid development of anti-CFA/I responses.

Acknowledgments

We thank David M. Hone, Institute of Human Virology, Medical Biotechnology Center, University of Maryland at Baltimore, for providing the described Salmonella vaccine vectors and Nancy Kommers for her assistance in preparing the manuscript.

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant AI-41123 and in part by Montana Agricultural Station and USDA Formula Funds.

Editor: R. N. Moore

Footnotes

Montana Agricultural Journal series no. 2001-58.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ables, G. P., D. Takamatsu, H. Noma, S. El-Shazly, H. K. Jin, T. Taniguchi, K. Sekikawa, and T. Watanabe. 2001. The roles of Nramp1 and Tnf-α genes in nitric oxide production and their effect on the growth of Salmonella typhimurium in macrophages from Nramp1 congenic and tumor necrosis factor-α−/− mice. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 21:53-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alpuche-Aranda, C. M., E. L. Racoosin, J. A. Swanson, and S. I. Miller. 1994. Salmonella stimulate macrophage macropinocytosis and persist within spacious phagosomes. J. Exp. Med. 179:601-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ascón, M. A., D. M. Hone, N. Walters, and D. W. Pascual. 1998. Oral immunization with a Salmonella typhimurium vaccine vector expressing recombinant enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K99 fimbriae elicits elevated antibody titers for protective immunity. Infect. Immun. 66:5470-5476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aste-Amezaga M., X. Ma, A. Sartori, and G. Trinchieri. 1998. Molecular mechanisms of the induction of IL-12 and its inhibition by IL-10. J. Immunol. 160:5936-5944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrera, L. F., I. Kramnik, E. Skamene, and D. Radzioch. 1994. Nitrite production by macrophages derived from BCG-resistant and -susceptible congenic mouse strains in response to IFN-gamma and infection with BCG. Immunology 82:457-464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benjamin, W. H., P. Hall, S. J. Roberts, and D. E. Briles. 1990. The primary effect of the Ity locus is on the rate of growth of Salmonella typhimurium that are relatively protected from killing. J. Immunol. 144:3143-3151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blackwell, J. M., C. H. Barton, J. K. White, T. I. Roach, M. A. Shaw, S. H. Whitehead, B. A. Mock, S. Searle, H. Williams, and A. M. Baker. 1994. Genetic regulation of leishmanial and mycobacterial infections: the Lsh/Ity/Bcg gene story continues. Immunol. Lett. 43:99-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bliss, S. K., B. A. Butcher, and E. Y. Denkers. 2000. Rapid recruitment of neutrophils containing prestored IL-12 during microbial infection. J. Immunol. 165:4515-4521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bost, K. L., and J. D. Clements. 1997. Intracellular Salmonella dublin induces substantial secretion of the 40-kilodalton subunit of interleukin-12 (IL-12) but minimal secretion of IL-12 as a 70-kilodalton protein in murine macrophages. Infect. Immun. 65:3186-3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, L. M., K. Kaniga, and J. E. Galán. 1996. Salmonella spp. are cytotoxic for cultured macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 21:1101-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciacci-Woolwine, F., L. S. Kucera, S. H. Richardson, N. P. Iyer, and S. B. Mizel. 1997. Salmonellae activate tumor necrosis factor alpha production in a human promonocytic cell line via a released polypeptide. Infect. Immun. 65:4624-4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtiss, R., S. M. Kelly, and J. O. Hassan. 1993. Live oral avirulent Salmonella vaccines. Vet. Microbiol. 37:397-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dueger, E. L., J. K. House, D. M. Heithoff, and M. J. Mahan. 2001. Salmonella DNA adenine methylase mutants elicit protective immune responses to homologous and heterologous serovars in chickens. Infect. Immun. 69:7950-7954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dybing, J. K., and D. W. Pascual. 1999. Role of endogenous interleukin-18 in resolving wild-type and attenuated Salmonella typhimurium infections. Infect. Immun. 67:6242-6248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eckmann, L., J. Fierer, and M. F. Kagnof. 1996. Genetically resistant (Ityr) and susceptible (Itys) congenic mouse strains show similar cytokine responses following infection with Salmonella dublin. J. Immunol. 156:2894-2900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elhofy, A., I. Marriott, and K. L. Bost. 2000. Salmonella infection does not increase expression and activity of the high affinity IL-12 receptor. J. Immunol. 165:3324-3332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forbes, J. R., and P. Gros. 2001. Divalent-metal transport by NRAMP proteins at the interface of host-pathogen interactions. Trends Microbiol. 9:397-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Govoni, G., S. Vidal, S. Gauthier, E. Skamene, D. Malo, and P. Gros. 1996. The Bcg/Ity/Lsh locus: genetic transfer of resistance to infections in C57BL/6J mice transgenic for the Nramp1Gly169 allele. Infect. Immun. 64:2923-2929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Govoni, G., F. Canonne-Hergaux, C. G. Pfeifer, S. L. Marcus, S. D. Mills, D. J. Hackam, S. Grinstein, D. Malo, B. B. Finlay, and P. Gros. 1999. Functional expression of Nramp1 in vitro in the murine macrophage line RAW264.7. Infect. Immun. 67:2225-2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gros, P., E. Skamene, and A. Forget. 1981. Genetic control of natural resistance to Mycobacterium bovis (BCG) in mice. J. Immunol. 127:2417-2421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hess, J., C. Ladel, D. Miko, and S. H. Kaufmann. 1996. Salmonella typhimurium aroA− infection in gene-targeted immunodeficient mice: major role of CD4+ TCR-αβ cells and IFN-γ in bacterial clearance independent of intracellular location. J. Immunol. 156:3321-3326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hess, J., I. Gentschev, D. Miko, M. Welzel, C. Ladel, W. Goebel, and S. H. Kaufmann. 1996. Superior efficacy of secreted over somatic antigen display in recombinant Salmonella vaccine induced protection against listeriosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:1458-1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoiseth, S. K., and B. A. D. Stocker. 1981. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature 291:238-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jabado, N., A. Jankowski, S. Dougaparsad, V. Picard, S. Grinstein, and P. Gros. 2000. Natural resistance to intracellular infections: natural resistance-associated macrophage protein 1 (Nramp1) functions as a pH-dependent manganese transporter at the phagosomal membrane. J. Exp. Med. 192:1237-1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kincy-Cain, T., J. D. Clements, and K. L. Bost. 1996. Endogenous and exogenous interleukin-12 augment the protective immune response in mice orally challenged with Salmonella dublin. Infect. Immun. 64:1437-1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mastroeni, P., A. Arena, G. B. Costa, M. C. Liberto, L. Bonina, and C. E. Hormaeche. 1991. Serum TNF alpha in mouse typhoid and enhancement of a Salmonella infection by anti-TNF alpha antibodies. Microb. Pathog. 11:33-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mastroeni, P., B. Villareal-Ramos, and C. E. Hormaeche. 1992. Role of T cells, TNF-α and IFN-γ in recall of immunity to oral challenge with virulent salmonellae in mice vaccinated with live attenuated aro− Salmonella vaccines. Microb. Pathog. 13:477-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mastroeni, P., B. Villarreal-Ramos, and C. E. Hormaeche. 1993. Effect of late administration of anti-TNF alpha antibodies on a Salmonella infection in the mouse model. Microb. Pathog. 14:473-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mastroeni, P., J. A. Harrison, J. H. Robinson, S. Clare, S. Khan, D. J. Maskell, G. Dougan, and C. E. Hormaeche. 1998. Interleukin-12 is required for control of the growth of attenuated aromatic-compound-dependent salmonellae in BALB/c mice: role of gamma interferon and macrophage activation. Infect. Immun. 66:4767-4776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monack, D. M., B. Raupach, A. E. Hromockyj, and S. Falkow. 1996. Salmonella typhimurium invasion induces apoptosis in infected macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:9833-9838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nauciel, C., and F. Espinasse-Maes. 1992. Role of gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha in resistance to Salmonella typhimurium infection. Infect. Immun. 60:450-454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pascual, D. W., V. H. Pascual, K. L. Bost, J. R. McGhee, and S. Oparil. 1993. Nitric oxide mediates immune dysfunction in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension 21:185-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pascual, D. W., D. M. Hone, S. Hall, F. W. van Ginkel, M. Yamamoto, N. Walters, K. Fujihashi, R. Powell, S. Wu, J. L. VanCott, H. Kiyono, and J. R. McGhee. 1999. Expression of recombinant Escherichia coli enterotoxigenic colonization factor antigen I by Salmonella typhimurium elicits a biphasic T helper cell response. Infect. Immun. 67:6249-6256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pascual, D. W., M. D. White, T. Larson, and N. Walters. 2001. Impaired mucosal immunity in L-selectin-deficient mice orally immunized with a Salmonella vaccine vector. J. Immunol. 167:407-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramarathinam, L., D. W. Niesel, and G. R. Klimpel. 1993. Salmonella typhimurium induces IFN-γ production in murine splenocytes: role of natural killer cells and macrophages. J. Immunol. 150:3973-3981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts, M., S. N. Chatfield, and G. Dougan. 1994. Salmonella as carriers of heterologous antigens, p. 27-58. In D. T. O'Hagan (ed.), Novel delivery systems for oral vaccines. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 37.Schodel, F., D. R. Milich, and H. Will. 1990. Hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid/pres-S2 fusion proteins expressed in attenuated Salmonella for oral vaccination. J. Immunol. 145:4317-4321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stobie, L., S. Gurunathan, C. Prussin, D. L. Sacks, N. Glaichenhaus, C. Y. Wu, and R. A. Seder. 2000. The role of antigen and IL-12 in sustaining Th1 memory cells in vivo: IL-12 is required to maintain memory/effector Th1 cells sufficient to mediate protection to an infectious parasite challenge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:8427-8432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tite, J. P., G. Dougan, and S. N. Chatfield. 1991. The involvement of tumor necrosis factor in immunity to Salmonella infection. J. Immunol. 147:3161-3164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tracey, K. J., and A. Cerami. 1993. Tumor necrosis factor, other cytokines and disease. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 9:317-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trinchieri, G., and P. Scott. 1999. Interleukin-12: basic principles and clinical applications. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 238:57-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.VanCott, J. L., S. N. Chatfield, M. Roberts, D. M. Hone, E. Hohmann, D. W. Pascual, M. Yamamoto, S. Yamamoto, H. Kiyono, and J. R. McGhee. 1998. Regulation of host immune responses by modification of Salmonella virulence genes. Nat. Med. 4:1247-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vidal, S., M. L. Tremblay, G. Govoni, S. Gauthier, G. Sebastiani, D. Malo, E. Skamene, M. Olivier, S. Jothy, and P. Gros. 1995. The Ity/Lsh/Bcg locus: natural resistance to infection with intracellular parasites is abrogated by disruption of the Nramp1 gene. J. Exp. Med. 182:655-666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu, S., D. W. Pascual, J. L. VanCott, J. R. McGhee, D. R. Maneval, Jr., M. M. Levine, and D. M. Hone. 1995. Immune responses to Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium vectors that express colonization factor antigen I (CFA/I) of enterotoxigenic E. coli in the absence of the CFA/I positive regulator cfaR. Infect. Immun. 63:4933-4938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu, S., D. W. Pascual, G. K. Lewis, and D. M. Hone. 1997. Induction of mucosal and systemic responses against human immunodeficiency virus type-1 gp120 in mice after oral immunization with a single dose of a Salmonella-HIV vector. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 13:1187-1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu, D., S. J. McSorley, S. N. Chatfield, G. Dougan, and F. Y. Liew. 1995. Protection against Leishmania major infection in genetically susceptible BALB/c mice by gp63 delivered orally in attenuated Salmonella typhimurium (AroA− AroD−). Immunology 85:1-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang, D. M., N. Fairweather, L. L., Button, W. R. McMaster, L. P. Kahl, and F. Y. Liew. 1990. Oral Salmonella typhimurium (AroA−) vaccine expressing a major leishmanial surface protein (gp63) preferentially induces T helper 1 cells and protective immunity against leishmaniasis. J. Immunol. 145:2281-2285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yap, G., M. Pesin, and A. Sher. 2000. Cutting edge: IL-12 is required for the maintenance of IFN-γ production in T cells mediating chronic resistance to the intracellular pathogen,Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol. 165:628-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]