Abstract

As a result of alternative trans splicing, three distinct LYT1 mRNAs are produced in Trypanosoma cruzi, two encoding the full-length LYT1 protein and the third encoding a truncated LYT1 protein lacking a possible signal sequence. Analysis of the three mRNAs in different developmental forms of the parasite revealed that the alternative processing events were regulated differently during the parasite life cycle.

Unlike those of most other eukaryotes, the protein-coding sequences of trypanosomes are organized into polycistronic transcription units containing either tandemly reiterated gene families or unique genes (2, 6, 10). Polycistronic primary transcripts are converted into translatable monocistronic mRNA by 5′-end trans splicing and 3′-end polyadenylation (3). trans splicing adds a 39-nucleotide (nt) miniexon sequence to the end of each mRNA, and based on cDNA sequence and genetic analysis, it is known that a conserved antigen (Ag) dinucleotide and one or more polypyrimidine (pPy) tracts are important cis-acting elements involved in the selection of the 3′ splice acceptor site (4, 5, 9, 11, 12). Although trans splicing is normally precise, there are instances where more than one 3′ splice acceptor site within an intergenic region is used and where splicing occurs at non-Ag acceptor sites (1, 7, 12).

We have recently reported the cloning, sequencing, and genetic analysis of the LYT1 gene of Trypanosoma cruzi (8). LYT1 is a single-copy gene and encodes a protein involved in a lytic pathway. LYT1 is dispensable in epimastigotes, but LYT1 null parasites are infection deficient, display accelerated in vitro development, and have diminished hemolytic activity at acidic pHs. How one protein influences such seemingly diverse biological processes is unclear. One possibility is that LYT1 protein (LYT1p) is a factor which regulates the expression of multiple genes encoding proteins of diverse function. Consistent with this idea is the presence of a possible nuclear localization sequence (NLS) that is homologous to the classical NLS of the simian virus 40 large T antigen (Fig. 1). Another possibility is suggested by the occurrence of multiple potential 3′ splice acceptor sites which, if used, would lead to expression of different LYT1p derivatives. One derivative would carry a possible amino-terminal signal sequence. The second would lack this element as a result of trans splicing within the protein coding sequence, leading to translation initiation from the ATG codon at position +85 within the protein coding sequence. Consequently, it is possible that two forms of the protein are produced: one secreted, consistent with a role in hemolysis, and a second nuclear, consistent with a role in development.

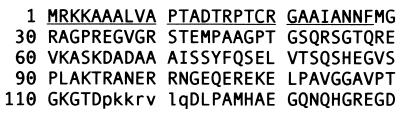

FIG. 1.

Amino-terminal sequence of LYT1p (CL Brenner strain) (8), showing the possible NLS from amino acids 126 to 132 (lowercase characters). The region of the protein removed as a result of alternative trans splicing is underlined.

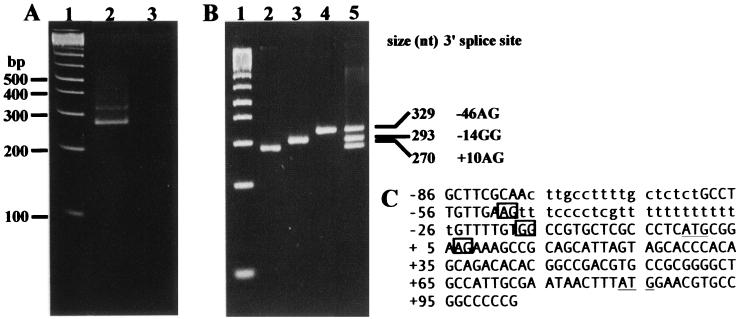

Our understanding of trans splicing in T. cruzi (5) and the nucleotide sequence of the LYT1 intergenic region strengthens the notion that two LYT1ps are produced. The 5′ flanking sequence upstream of the ATG translational start site of LYT1 includes two significant pPy tracts which could direct splicing to both position −46 and position +10 (relative to the first ATG at position +1). The full-length protein would be produced from the mRNA trans spliced at position −46, and truncated LYT1p lacking the amino-terminal signal sequence would be produced from mRNA trans spliced at position +10. To determine if both LYT1 mRNAs were produced and to map the site of miniexon addition, PCR amplification of reverse-transcribed LYT1 mRNA was carried out. Total RNA isolated from mid-log CL Brenner epimastigotes and clone L16 LYT1 null parasites (8) was reverse transcribed using an oligonucleotide complementary to nt +648 to +672 of the LYT1 coding sequence (LYT1 3′). The first strand of LYT1 cDNA was then amplified using primers homologous to nt 7 to 28 of the miniexon sequence (ME 21) and complementary to nt +239 to +258 of the LYT1p coding sequence (LYT1 2). Two amplification products were detected (Fig. 2A), suggesting the existence of multiple mature LYT1 mRNAs. As expected, no amplification products were detected from clone L16, which lacks LYT1. To determine whether multiple miniexon addition sites were used, the amplification products were cloned and the nucleotide sequences were determined (Fig. 2C). Three different clones were obtained (Fig. 2B), and sequence analysis revealed that the cDNAs represented LYT1 mRNAs that were trans spliced at positions −46 and −14 of the LYT1 intergenic regions and at position +10 within the LYT1 open reading frame (Fig. 2C). Consequently, the full-length LYT1p carrying the potential signal sequence could be expressed from the transcripts spliced at positions −46 and −14, while the truncated version lacking the signal sequence could be expressed from the transcript spliced at +10. The LYT1 transcript spliced at position −14 (293 bp) was not detected by ethidium bromide staining, suggesting that a lower amount of this transcript is produced than of the other two products (329 bp and 270 bp). Based on nucleotide sequences previously reported, researchers have shown that 5′ flanking sequences of both the LYT1a and LYT1b alleles have GG at position −14 (8). Thus, splicing at position −14 was unexpected, since the intergenic sequences did not carry a consensus AG 3′ splice acceptor sites. Therefore, a minority of the LYT1 transcripts are spliced at a nonconsensus miniexon addition site. Note that a large pPy tract is present upstream of the GG dinucleotide at position −14 (Fig. 2C), perhaps accounting in part for its utilization as a 3′ acceptor site.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of LYT1 cDNA clones. (A and B) Ethidium bromide-stained 4% agarose gels. (A) Lane 1, 100-base ladder size standards (Roche); lanes 2 and 3, amplification of mRNA isolated from wild type-parasites (lane 2) and L16 LYT1 null parasites (lane 3) (8). (B) PCR products generated using ME 21 and LYT1 2 as primers and cloned LYT1 cDNAs as templates. Lane 1, 100-base ladder size standards (Roche); lane 2, +10 cDNA amplification products; lane 3, −14 cDNA amplification products; lane 4, amplification products of −46 cDNA clones. The pooled amplification products are displayed in lane 5. The lengths of the amplification products are listed to the right of the image. (C) LYT1a allele (CL Brenner strain) 5′ flanking sequence and a portion of the coding sequence. Translation initiation codons at positions +1 and +85 are underlined. The three 3′ splice acceptor sites are shown in boxes. Possible pPy tracts are in lowercase.

Comparisons of the different LYT1 cDNA sequences with the LYT1a and LYT1b allele sequences verified that all spliced variants of the LYT1 mRNAs were produced from both alleles.

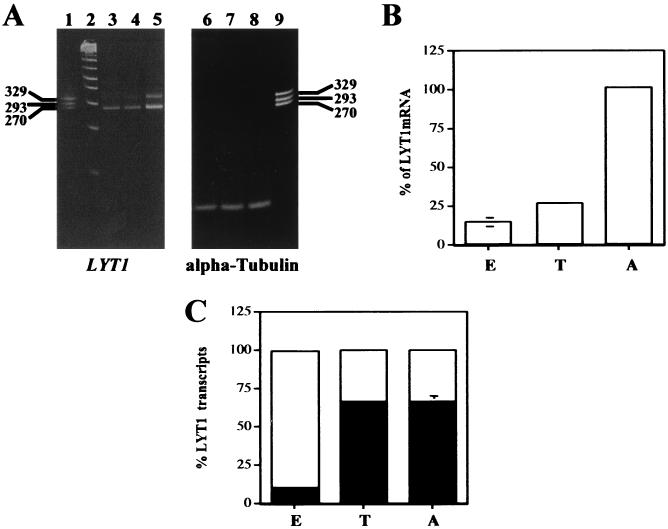

The occurrences of alternative LYT1 splicing led us to compare the usage of the different splice acceptor sites during the parasite life cycle. Reverse transcription (RT)-RT PCR analysis was completed using the LYT1 3′ oligonucleotide to prime RT and ME 21 and LYT1 2 oligonucleotides for amplification. Epimastigote, trypomastigote, or amastigote total RNA was used as the template for the reactions (Fig. 3). The results were quantified by densitometry (Sigma Gel software, version 1.0) and showed that the LYT1 mRNAs were most highly expressed in amastigotes, suggesting that expression of the gene was upregulated in this form of the parasite (Fig. 3B). A similar analysis of the alpha-tubulin transcripts showed that they were equally expressed in all developmental forms (Fig. 3A, right panel). To determine the relative amount of each LYT1 mRNA in the different developmental forms, we compared the relative abundance of the 329-bp and 270-bp RT-PCR products (Fig. 3C). The results showed that the transcript encoding the full-length LYT1p (329-bp RT-PCR product) represented 65% of the total LYT1 mRNA in trypomastigotes and amastigotes but only 10.5% in epimastigotes. This result is consistent with the previous observation of significantly less hemolytic activity at acid pH in this developmental stage of the parasite (8).

FIG. 3.

Expression of LYT1 mRNA derivatives during the parasite life cycle. (A) Ethidium bromide-stained 4% agarose gels of LYT1 and alpha-tubulin RT-PCR products. Lane 1, pooled 270-, 293-, and 329-bp PCR products; lane 2, 100-base ladder (Roche). Lanes 3 to 5 display the LYT1 RT-PCR products which were generated using identical amounts of total RNA isolated from the epimastigotes (lane 3), trypomastigotes (lane 4), and amastigotes (lane 5). Lanes 6 to 8 display the alpha-tubulin RT-PCR products which were generated using identical amounts of total RNA isolated from epimastigotes (lane 6), trypomastigotes (lane 7), and amastigotes (lane 8). Lane 9 displays the pooled LYT1 RT-PCR products. (B) Quantitation of the total LYT1 RT-PCR products (270 bp plus 329 bp) shown in panel A. Each sample was normalized to the alpha-tubulin products isolated from the same developmental forms. E, epimastigotes; T, trypomastigotes; A, amastigotes. (C) Measurement of the relative abundance of the 270-bp (open bars) and 329-bp (filled bars) LYT1 RNAs during the parasite life cycle. E, epimastigotes; T, trypomastigotes; A, amastigotes. The results shown in panels B and C are the averages of three independent experiments (P < 0.001).

The production of different LYT1p derivatives, one having a possible export signal sequence and the other not, is consistent with the notion that both intracellular (cytosolic or nuclear) and secreted forms of the protein are produced and may explain its role in such widely diverse processes as hemolysis and developmental regulation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a USPHS grant (A126578) award to J.S., a grant (CONACyT, México; 34837-N) award to R.M.-C., and grant PB98-0479, awarded to A.G. by the Spanish Ministry of Education and Culture. R.M.-C. is the recipient of Fogarty (1F05TWO5274-01) and International Training & Research in Emerging Infectious Diseases (ITREID) postdoctoral fellowships.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Deshler, J. O., and J. J. Rossi. 1991. Unexpected point mutations activate cryptic 3′ splice sites by perturbing a natural secondary structure within a yeast intron. Genes Dev. 5:1252-1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzalez, A., T. J. Lerner, M. Huecas, B. Sosa-Pineda, N. Noqueira, and P. M. Lizardi. 1985. Apparent generation of a segmented mRNA from two separate tandem gene families in Trypanosoma cruzi. Nucleic Acids Res. 13:5789-5804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang, J., and L. H. Van der Ploeg. 1991. Maturation of polycistronic pre-mRNA in Trypanosoma brucei: analysis of trans splicing and poly(A) addition at nascent RNA transcripts from the hsp70 locus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:3180-3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang, J., and L. H. Van der Ploeg. 1991. Requirement of a polypyrimidine tract for trans splicing in trypanosomes: discriminating the PARP promoter from the immediately adjacent 3′ splice acceptor site. EMBO J. 10:3877-3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hummel, H. S., R. D. Gillespie, and J. Swindle. 2000. Mutational analysis of 3′ splice site selection during trans-splicing. J. Biol. Chem. 275:35522-35531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imboden, M. A., P. W. Laird, M. Affolter, and T. Seebeck. 1987. Transcription of the intergenic regions of the tubulin gene cluster of Trypanosoma brucei: evidence for a polycistronic transcription unit in a eukaryote. Nucleic Acids Res. 15:7357-7368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapler, G. M., K. Zhang, and S. M. Beverley. 1987. Sequence and S1 nuclease mapping of the 5′ region of the dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase gene of Leishmania major. Nucleic Acids Res. 15:3369-3383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manning-Cela, R., A. Cortés, E. González-Rey, W. C. Van Voorhis, J. Swindle, and A. González. 2001. LYT1 protein is required for efficient in vitro infection by Trypanosoma cruzi. Infect. Immun. 69:3916-3923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matthews, K. R., C. Tschudi, and E. Ullu. 1994. A common pyrimidine-rich motif governs trans-splicing and polyadenylation of tubulin polycistronic pre-mRNA in trypanosomes. Genes Dev. 8:491-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muhich, M. L., and J. C. Boothroyd. 1988. Polycistronic transcripts in trypanosomes and their accumulation during heat shock: evidence for a precursor role in mRNA synthesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:3837-3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schürch, N., A. Hehl, E. Vassella, R. Braun, and I. Roditi. 1994. Accurate polyadenylation of procyclin mRNAs in Trypanosoma brucei is determined by pyrimidine-rich elements in the intergenic regions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:3668-3675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vassella, E., R. Braun, and I. Roditi. 1994. Control of polyadenylation and alternative splicing of transcripts from adjacent genes in a procyclin expression site: a dual role for polypyrimidine tracts in trypanosomes? Nucleic Acids Res. 22:1359-1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]