Abstract

Experimental and clinical studies suggest that influenza A virus promotes Streptococcus pneumoniae-induced otitis media; however, the mechanism underlying this synergistic interaction has not been completely defined. In this study, glycoconjugate expression patterns were evaluated on the cell surface in the chinchilla eustachian tube (ET) lumen of a cohort challenged intranasally (i.n.) with S. pneumoniae type 6A, which is predominantly transparent and a cohort with an antecedent influenza A virus infection, followed by i.n. inoculation with S. pneumoniae. The labeling patterns obtained with six lectin probes revealed that the binding of Bandeiraea simplicifolia lectin II, succinylated wheat germ agglutinin, and peanut agglutinin were significantly increased in the lumenal surface of the ET in the cohort infected with both pathogens compared to the cohort inoculated with only S. pneumoniae, which indicated that N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and d-galactose residues were exposed. A significant decreased labeling with Sambucus nigra agglutinin in the combined influenza A virus and pneumococcus infection cohort suggested that there were few sialic acid residues remaining in the ET epithelium. In addition, the colonial opacity of S. pneumoniae during the disease course was examined. The opaque phenotype was predominant among the pneumococcus isolates from the middle-ear fluid in the cohort infected with the both pathogens. Together, these data suggest that the synergic effect of influenza A virus and S. pneumoniae on the changes of the carbohydrate moieties in the ET epithelium and that the selection of the opaque variant may facilitate the pneumococcal invasion of the middle ear.

Considerable epidemiologic, clinical, and laboratory evidence suggests that influenza A virus promotes Streptococcus pneumoniae-induced otitis media (OM) (4, 5, 6, 10, 12, 23). Several possible mechanisms have been proposed to explain this phenomenon, including viral compromise of eustachian tube (ET) mucosal integrity, resulting in impaired clearance function with the development of negative middle ear pressure, and viral suppression of polymorphonuclear leukocyte function (1, 2, 7, 11, 18, 19). We and others have demonstrated that influenza A virus infection also promotes a significant increase in nasopharyngeal (NP) colonization and an increased incidence and severity of S. pneumoniae OM in the chinchilla, as well as in human adult subjects (10, 23, 27). Moreover, our recent report indicates that the effects of influenza A virus on the pathogenesis of S. pneumoniae-induced OM in the chinchilla vary depending on the colonial opacity phenotype of the S. pneumoniae inoculum (21). Our data demonstrate that there is no significant difference in the level of NP colonization and induction of OM between the opaque and transparent variants unless there is a prior challenge with influenza A virus. Subsequent to influenza A virus infection, there is an increased ability of opaque variants to colonize and persist in the nasopharynx and middle ear compared to the transparent phenotype. Despite these recent advances, however, much more remains to be learned about the interactions between influenza A virus and S. pneumoniae in the pathogenesis of OM.

Recently, our laboratory, using a S. pneumoniae neuraminidase-deficient mutant as a tool, has begun to define the role of S. pneumoniae neuraminidase in the structural alteration of cell surface carbohydrates in the ET epithelium. Our data indicate that disruption of the S. pneumoniae nanA neuraminidase gene results in a diminished ability of the bacteria to alter the surface carbohydrates in the ET epithelium, which coincides with a diminished ability to colonize the chinchilla nasopharynx (24). Influenza A virus also produces neuraminidase, and a recent report indicates that influenza A virus modifies the carbohydrate architecture of the epithelium as indicated by an increase in lectin labeling with peanut agglutinin (PNA), succinylated wheat germ agglutinin (SWGA), and Bandeiraea simplicifolia lectin II (BSL II) in murine NP mucosa, which may also be associated with an increased NP colonization by S. pneumoniae and nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (13).

It is generally believed that OM pathogens must progress from their NP carrier status, retrograde ascend the ET, and invade the middle ear to cause disease. However, very little is known of this process. The purpose of this study was to determine whether a synergistic effect between influenza A virus and S. pneumoniae impacts the changes of the cell surface glycoconjugate structure in the ET epithelium to a greater extent than that exhibited by each pathogen alone. Six lectin probes were used as part of this study to examine alterations of the cell surface carbohydrates in the chinchilla ET lumen subsequent to an influenza A virus infection of the nasopharynx, followed by intranasal (i.n.) challenge with S. pneumoniae type 6A. Additionally, the bacterial concentrations (CFU/milliliter) in middle-ear fluid (MEF) and in the NP lavage fluid and the inflammatory cell numbers (cells/cubic millimeter) in MEF or bullae lavage samples were determined. Finally, the colonial opacity phenotype of S. pneumoniae type 6A isolated from chinchilla NP lavage fluid and MEF were assessed during the course of experimental OM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

Chinchillas (Chinchilla lanigera) (220 to 450 g) free of middle-ear disease as determined by otoscopy and tympanometry were used for this study. Two experimental cohorts consisting of nine chinchillas each were inoculated i.n. with influenza A virus, or diluent without virus, followed 4 days later by i.n. inoculation with the S. pneumoniae type 6A. A third cohort of nine chinchillas was inoculated i.n. with influenza A virus, three chinchillas were sacrificed on day 3 after influenza A virus infection for lectin histochemistry study, and six chinchillas were i.n. inoculated with 0.5 ml of Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) on day 4 after the virus infection and served as an influenza A virus only group. A fourth cohort of three chinchillas was inoculated i.n. with the virus diluent, followed 4 days later by i.n. inoculation with DPBS, and served as a normal control group for this study. Three chinchillas (preselected and randomized) from each of the experimental cohorts were evaluated for NP colonization and OM on days 1, 3, and 7 after i.n. inoculation of S. pneumoniae type 6A. The colonization status of the nasopharynx and invasion of the middle ears were determined by enumerating the CFU of S. pneumoniae per milliliter of each lavage fluid as described below. The colony opacity of S. pneumoniae type 6A isolates in the NP lavage fluid and MEF from these two cohorts was examined and compared during the course of experimental OM. Finally, ET specimens from all cohorts (three chinchillas each from the experimental cohorts, two from the influenza A virus only group, and one from the normal control group) were collected at each time point for lectin histochemical analysis of changes of the cell surface carbohydrate architecture.

i.n. inoculation with influenza A virus.

Influenza virus A/Alaska/6/77 (H3N2) has previously been used by our laboratories and has been described in detail (7, 19). Briefly, the virus stock was diluted in sterile Eagle minimal essential medium (Whittaker, Walkersville, Md.). One of the experimental cohorts of nine chinchillas was inoculated i.n. with 0.2 ml of a virus suspension containing ca. 6 × 106 PFU of influenza A virus/ml. The other experimental cohort of nine chinchillas received 0.2 ml of Eagle minimal essential medium without virus. A third cohort of six chinchillas also received 0.2 ml of the virus suspension without the subsequent inoculation with S. pneumoniae and served as influenza A virus only group for this study.

S. pneumoniae inoculation.

S. pneumoniae type 6A (EF3114), (originally provided by B. Anderson, Department of Clinical Immunology, University of Göteborg, Göteborg, Sweden) was used for these experiments and has been described in detail previously (3). The colonial morphology (opaque or transparent) of S. pneumoniae type 6A was originally determined by Jeffrey Weiser, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. S. pneumoniae type 6A is predominantly transparent (90%) and was confirmed prior to inoculation by using the method established by Weiser et al. (25, 29). The opacity phenotype of S. pneumoniae type 6A isolated from the lavage or MEF samples at various time points was also assessed by using this method. For inoculum preparation, log-phase cultures were prepared from chocolate agar plate subcultures, by inoculating Todd-Hewitt broth supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) with S. pneumoniae type 6A. After a 3-h incubation, the cultures were centrifuged at 3,500 × g for 20 min, washed twice, and resuspended in DPBS. The concentration of S. pneumoniae (expressed as CFU per milliliter) was determined by standard dilution and plate count. At 4 days after i.n. challenge with influenza A virus, the virus-infected and non-virus-infected chinchillas were inoculated i.n. with 0.5 ml of the S. pneumoniae type 6A suspension containing 5 × 107 CFU/ml. All virus-inoculated animals were housed separately from the cohort receiving S. pneumoniae type 6A only.

Assessment of NP colonization and invasion of the middle ear.

Three chinchillas, preselected and randomized, were evaluated by tympanocentesis and NP lavage on days 1, 3, and 7 after inoculation with S. pneumoniae type 6A as previously described (23). Tympanocentesis was first performed on both ears of each of the three chinchillas by aspiration with a tuberculin syringe fitted with a 25-gauge needle. If no MEF was present, the bullae were lavaged with 0.5 ml of prewarmed sterile saline. Subsequent to tympanocentesis, NP lavage was performed on each chinchilla as described previously (23). Chinchillas were not subjected to repeated tympanocentesis or lavage. Tympanocentesis and bulla lavage were always performed before NP lavage to prevent contamination of the middle ear. The MEF or lavage samples and the NP lavage samples were cultured on chocolate agar plates by overnight incubation in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2, and the concentrations of S. pneumoniae in the samples were determined by standard dilution and plate count. Inflammatory cells in MEF or bullae lavage samples were enumerated with a hemocytometer. The colonial opacity phenotype was determined by the method of Weiser et al. (29).

Lectin histochemistry.

At each time point the chinchillas were sacrificed and perfused intracardially with 10% neutral-buffered formalin, and the temporal bones removed. The ETs were dissected and kept in the same fixative for 2 days. The specimens were further processed for conventional paraffin embedding (17). Serial sections of the pharyngeal orifice, mid-portion, and tympanic orifice of the ETs were cut to a thickness of 4 μm, mounted on glass slides, and dried at 50°C for 30 min. Sections were deparaffinized with Histo-Clear (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, Ga.) three times for 5 min each time and then washed twice in absolute ethanol for 2 min. The sections were dehydrated in 95, 80, and 70% ethanol and rinsed in distilled water for 2 min. To quench any endogenous peroxidase, sections were incubated with 3% hydrogen peroxide in absolute methanol for 20 min and placed in 0.05 M Tris-buffered saline (TBS; pH 7.4). The sections were then incubated in 2% bovine serum albumin-TBS solution at 37°C for 20 min and then probed with diluted, biotinylated lectins (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.) at 37°C for 1 h and then overnight at 4°C. Lectins used in this study are listed in Table 1, and they have been described previously (16, 17). The slides were equilibrated to room temperature and washed three times with TBS (for 5 min each time), incubated with prepared avidin-biotin complex (Vector Laboratories) at 37°C for 1 h, washed three times with TBS (5 min each), incubated with diaminobenzidine solution (Vector ABC kit) at room temperature for 5 min, and finally rinsed in hot tap water. Slides were mounted with Crystal Mount mounting medium (Biomeda Co., Foster City, Calif.). A scale of 1, 2, and 3 (for weak, moderate, and strong, respectively) was used to compare the intensity of the lectin labeling.

TABLE 1.

Lectins used in this study

| Lectin name | Abbreviation | Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Sambucus nigra agglutinin | SNA | Neu5Ac(α2-6)Gal |

| Wheat germ agglutinin | WGA | GlcNAc(β1-4), NeuAc |

| Succinylated wheat germ agglutinin | SWGA | GlcNAc(β1-4) |

| Bandeiraea (Griffonia) simplicifolia lectin II | BSL II | GlcNAc(β1-4) |

| Peanut agglutinin | PNA | Gal(β1-3)GalNAc |

| Gal(β1-4)GlcNAc | ||

| Erythrina cristagalli lectin | ECL | Gal(β1-4)GlcNAc |

Statistics.

Chi-square or Fisher exact test analysis was used to examine the differences of the proportion in the alteration of cell surface carbohydrates of the ETs between chinchillas inoculated i.n. with S. pneumoniae alone and S. pneumoniae in combination with an antecedent influenza A virus. The Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used to compare the difference in S. pneumoniae concentration in nasal lavage samples and the inflammatory cells in MEF or lavage samples between these two cohorts. A P value of <0.05 was accepted as the minimal level of significance.

RESULTS

Effect of influenza A virus on NP colonization and invasion of the middle ear of S. pneumoniae type 6A and inflammation of the middle ear.

The impact of an antecedent influenza A virus infection on both NP colonization and invasion of the middle ear was essentially in accordance with our previous report that influenza A virus infection of the nasopharynx results in a significant increase in S. pneumoniae type 6A NP colonization and the development of OM (23). On day 1 after i.n. challenge with S. pneumoniae, the concentration (geometric mean) of S. pneumoniae in nasal lavage fluid from the cohort with a prior influenza A virus infection was approximately 2 log units higher (5.2 × 106 CFU/ml) than that of the cohort infected with S. pneumoniae only (4.8 × 104 CFU/ml; P < 0.05). However, there was no statistical significant difference in S. pneumoniae concentrations in nasal lavage fluid on days 3 and 7 after S. pneumoniae i.n. inoculation. The bacterial concentrations in nasal lavage fluids from those infected with S. pneumoniae alone were 7.4 × 105 CFU/ml on day 3 and 7.1 × 105 CFU/ml on day 7 postinoculation, whereas in the cohort infected with both pathogens were 3.8 × 106 CFU/ml on day 3 and 1.1 × 106 CFU/ml on day 7 postchallenge. Seven of nine chinchillas infected with the combined influenza A virus and S. pneumoniae type 6A developed OM on days 1, 3, and 7 after i.n. challenge. Two chinchillas developed OM with unilateral ear infection on day 1, three chinchillas on day 3 had bilateral ear infections, and two chinchillas on day 7 had a unilateral ear infection after i.n. S. pneumoniae challenge. By comparison only three of nine chinchillas inoculated with S. pneumoniae type 6A alone developed OM on day 3 after the challenge, two chinchillas developed OM with bilateral ear infection and one chinchilla with a unilateral ear infection. The 10 infected ears from the cohort challenged with influenza A virus and S. pneumoniae type 6A had a concentration (geometric mean) of 3.8 × 106 CFU of MEF/ml. The five infected ears from the S. pneumoniae type 6A only cohort had a concentration of 6.2 × 103 CFU/ml. The inflammatory cell concentrations (geometric mean ± the standard error of the mean) in MEF or bullae samples in the cohort inoculated with S. pneumoniae only were 31 ± 21 cells/mm3 on day 1, 385 ± 178 cells/mm3 on day 3, and 262 × 107 cells/mm3 on day 7, whereas those in the cohort infected with the combined influenza A virus and S. pneumoniae were 307 ± 138 cells/mm3 on day 1, 1,645 ± 782 cells/mm3 on day 3, and 2,793 ± 1,281 cells/mm3 on day 7. There was no statistically significant difference in the concentration of inflammatory cells in MEF samples between these two cohorts. In contrast, there were no detectable inflammatory cells in the bullae lavage samples in the control cohort. Inflammatory cell concentrations in the lavage sample were <5 cells/mm3 in the cohort infected with influenza virus only during this study period.

Effect of influenza A virus on selection of opacity phenotypes of S. pneumoniae.

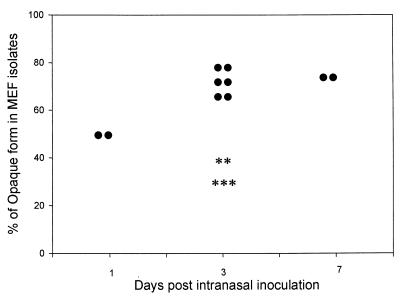

S. pneumoniae undergoes spontaneous phase variation between a transparent and an opaque colony phenotype. Transparent variants demonstrate an increased ability to adhere to human lung epithelial cells and are selected for during NP colonization (8). The opaque phenotype, however, is characteristically more virulent and is associated with invasive infection in the mouse model (14). In this study, the role of influenza A virus in the selection of opacity phenotypes of pneumococcus during the development of OM was examined. The inoculum was 90% transparent phenotype, as is characteristic of this strain (25). A predominance of the opaque phenotype was evident for pneumococci isolated from MEF in the cohort infected with the combined influenza A virus and S. pneumoniae. On day 1 after i.n. inoculation, 50% of the isolates from two MEF samples were the opaque phenotype and on day 3 and day 7 after i.n. inoculation, opaque form was the predominant phenotype (65 to 80%) in eight MEF samples from this cohort. In contrast, in the cohort infected with S. pneumoniae alone, only 30 to 40% of the isolates were opaque form from five MEF samples on day 3 postchallenge (Fig. 1). However, there was no significant impact of influenza A virus on selection of the opacity phenotypes of the NP pneumococcal isolates. In the cohort infected with S. pneumoniae alone 70 to 80% of the NP isolates on days 1, 3, and 7 after S. pneumoniae challenge had the transparent phenotype, and in the cohort infected with both pathogens 60 to 70% of the NP isolates had the transparent phenotype during the experimental period.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of pneumococcus opacity phenotype in MEF samples from the cohort inoculated i.n. with S. pneumoniae type 6A alone (✽) and the cohort inoculated i.n. with S. pneumoniae type 6A after a prior influenza A virus infection (•).

Lectin histochemistry.

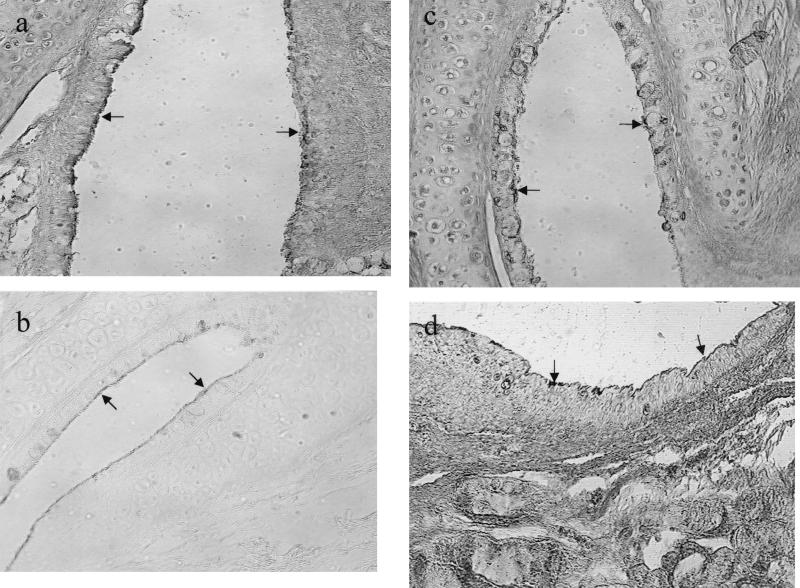

The lectin histochemistry of the normal chinchilla ET has been described previously (17). The epithelial cell surface of the ET in the normal chinchilla is not rich in N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) residues and therefore, does not react with SWGA, BSL II, or PNA lectin probes. The epithelium of the lumen of the entire ET from normal control chinchillas, during the present study, was intensely labeled with the Sambucus nigra agglutinin (SNA) and moderately labeled wheat germ agglutinin (WGA)-lectin probes, indicating that intact sialic acid residues were present. The weak labeling with SWGA, BSL II, and PNA and a decreased labeling of SNA was found in the ETs of three chinchillas on day 3 after i.n. inoculation of influenza A virus, which suggested that part of the terminal sialic acid residues were removed from the epithelial cell surface (Fig. 2). As expected from our previous report (17), i.n. inoculation of S. pneumoniae resulted in positive lectin labeling with SWGA, BSL II, and PNA of the ETs, primarily in the roof and neck region and, to a lesser extent, the floor (inferior) portion of the ET lumen. The combination of an antecedent influenza A virus and S. pneumoniae i.n. inoculation, however, not only dramatically increased the intensity of the labeling with SWGA, BSL II, and PNA of the epithelial cells lining the lumen of the ET compared to the normal control cohort but also changed the distribution patterns of the lectin labeling in the entire ET epithelium, suggesting that GlcNAc residues were significantly exposed. In addition, a significant decreased labeling with SNA was found in the ETs from the combined influenza A virus- and S. pneumoniae-infected cohort compared to that of the normal control cohort. The results are described below and are summarized in Table 2.

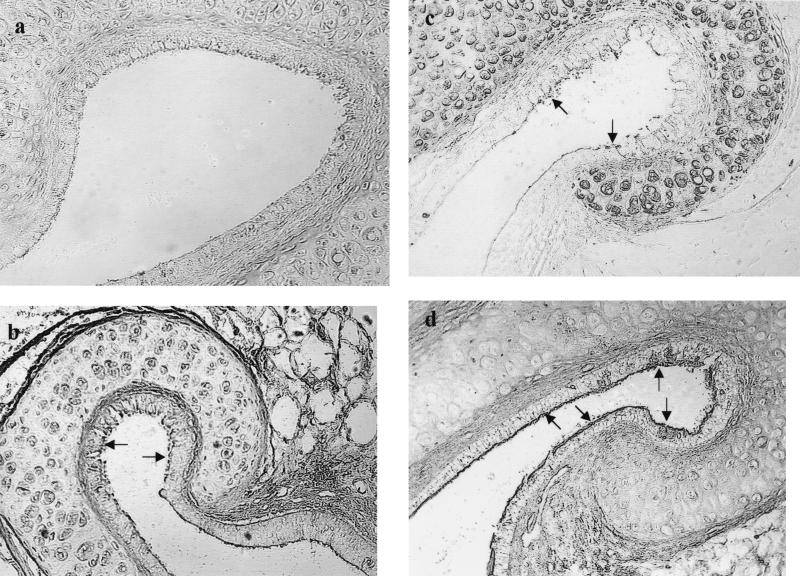

FIG. 2.

Alteration of lectin labeling of ET on day 3 after i.n. challenge of influenza A virus (magnification, ×160). (a) Weak labeling of SNA at the pharyngeal portion (arrows); (b) weak positive labeling of SWGA at the tympanic portion (arrows); (c) weak and focal labeling of BSL II at the tympanic portion (arrows); (d) weak labeling of PNA at the pharyngeal portion (arrows).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of the incidence and intensity of the lectin labeling in ETs from the chinchillas inoculated i.n. with S. pneumoniae with or without a prior influenza A virus infection

| Lectin | Ratinga | No. of ETs with the lectin labeling patternb

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

S. pneumoniae infection

|

Influenza A virus + S. pneumoniae infection

|

||||||

| Pharyngeal orifice | Mid-portion | Tympanic orifice | Pharyngeal orifice | Mid-portion | Tympanic orifice | ||

| SNA | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 4 | 6 | 5 | |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 14** | 12** | 13** | |

| BSL II | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10** | 10** | 8** |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 6 | |

| 1 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 2 | 4 | 4 | |

| SWGA | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 12** | 10* | 6 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 8 | |

| 1 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| PNA | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 12** | 8 | 4 |

| 2 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 12 | |

| 1 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

A rating scale of the intensity of lectin labeling: 3, strong staining; 2, moderate staining; and 1, weak staining (compared to that of the normal control cohort).

*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (compared to the S. pneumoniae cohort).

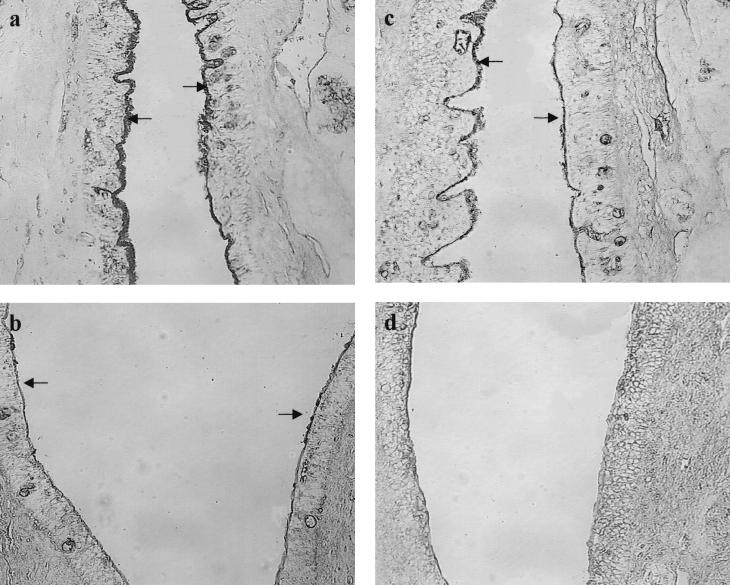

(i) Sialic acid-specific lectin (SNA).

All of the normal control chinchillas demonstrated intact sialic acid residues, as indicated by an intense labeling pattern with SNA along the entire surface of the ET in this study (Fig. 3a). In the influenza A virus only infection cohort, among the total of six ETs evaluated on days 1, 3, and 7 after i.n. challenge with PBS instead of S. pneumoniae, three ETs showed weak SNA labeling at the NP and mid-portion on days 1 and 3 (Fig. 3b), whereas the other three ETs with moderate SNA labeling compared to the normal control cohort. In the S. pneumoniae-inoculated cohort, only 2 of 18 (11%) ETs examined showed weak SNA labeling on days 1 and 3 after i.n. challenge, whereas the majority of the ETs (78%) showed moderate labeling (Fig. 3c). However, in the cohort infected with influenza A virus and S. pneumoniae, 14 of the 18 (78%) ETs at the pharyngeal portion, 12 of the 18 ETs (67%) at the mid-portion, and 13 of the 18 ETs (72%) at the tympanic portion showed significantly decreased intensity labeling on days 1, 3, and 7 after S. pneumoniae challenge (Fig. 3d). Metaplasia was observed in the epithelium of the pharyngeal and mid-portion of the ETs in the influenza A virus cohort and in the cohort with S. pneumoniae and influenza A virus infection. The significant decreased intensity of SNA labeling in the dual-pathogen-infected cohort not only was observed on days 1 and 3 and also on day 7 after S. pneumoniae challenge when the NP colonization reached the same level as that in the S. pneumoniae infected cohort, thus suggesting that the changed SNA labeling patterns were not due to differences in the concentration of bacteria in the nasopharynx.

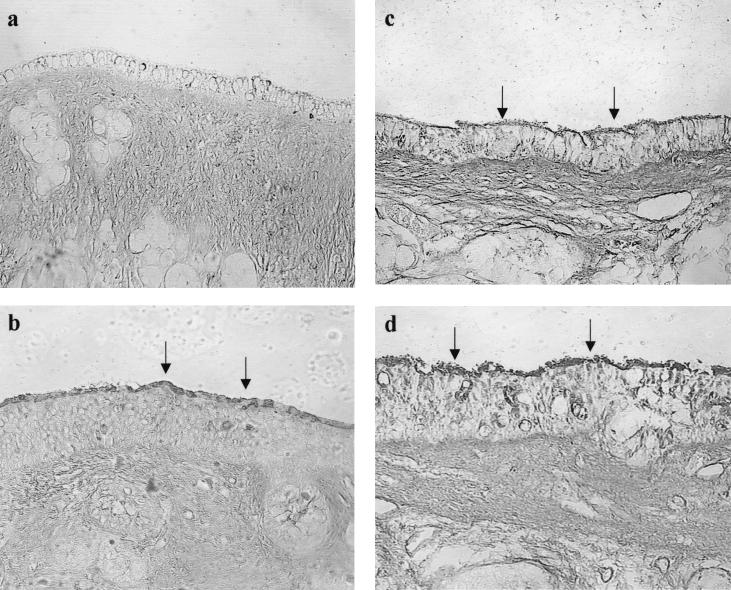

FIG. 3.

Pharyngeal portion of the ET (magnification, ×160). (a) Strong labeling of SNA of the normal control cohort 1 day after inoculation of Sterile PBS (arrows); (b) weak labeling of SNA on 1 day after i.n. inoculation of PBS in the cohort with prior influenza A virus infection (arrows); (c) moderate labeling of SNA on day 1 after i.n. inoculation of S. pneumoniae type 6A without a prior influenza A virus infection (arrows); (d) weak to no labeling of SNA on day 1 after i.n. inoculation of S. pneumoniae type 6A with a prior influenza A virus infection.

(ii) Sialic acid and GlcNAc-specific lectin (WGA).

In the normal cohort, moderate labeling with WGA on the entire surface of the ET was observed. In the influenza A virus only cohort, the intensity of WGA labeling was the same as that of the normal control cohort. Intensive labeling with WGA along the entire surface of the ET was noted in the cohort infected with influenza A virus and S. pneumoniae, as well as the cohort infected with S. pneumoniae alone, compared to that of the normal control cohort. There was no significant difference in the intensity of WGA labeling between these two cohorts.

(iii) GlcNAc-specific lectin (SWGA and BSL II).

The ET epithelium in the normal control cohort did not react with these two GlcNAc-specific lectins (Fig. 4a and Fig. 5a). In the influenza A virus infected cohort, six ETs demonstrated weak labeling of SWGA and BSL II at the NP portion, and focal labeling in the roof and neck portion of the ET (Fig. 4b and Fig. 5b). In the S. pneumoniae only inoculated cohort, only two ETs from the chinchillas which developed OM on day 3 after i.n. challenge was labeled strongly with SWGA staining and moderately with BSL II. Of the 18 ETs examined, 16 (89%) showed weak labeling with BSL II at the pharyngeal portion and focal labeling at the mid portion and tympanic orifice (Fig. 5c). Of 18 ETs, 14 (78%) showed weak labeling of SWGA (Fig. 4c). In contrast, in the cohort infected with both pathogens, 10 of 18 (56%) ETs at the pharyngeal and mid-portion and 8 of 18 (44%) ETs at the tympanic portions showed strong labeling of BSL II, along the entire ET on days 1, 3, and 7 after S. pneumoniae challenge (Fig. 5d). The increased intensity of SWGA labeling was also observed in this cohort: 12 of 18 ETs (67%) at the pharyngeal portion, 10 of 18 ETs (56%) at the mid-portion and 6 of 18 ETs (33%) at the tympanic portion showed strong labeling with SWGA (Fig. 4d). The data indicated that the dual pathogen infection results in an increased incidence, intensity, and duration of labeling with these lectin probes.

FIG. 4.

Tympanic portion of ET (magnification, ×160). (a) No labeling with SWGA of the normal control cohort 3 days after i.n. inoculation with sterile PBS; (b) weak and focal labeling with SWGA 3 days after i.n. inoculation with PBS in the cohort with a prior influenza A virus infection (arrows); (c) weak staining with SWGA 3 days after i.n. inoculation with S. pneumoniae type 6 A only (arrows); (d) strong labeling with SWGA 3 days after i.n. inoculation of S. pneumoniae type 6 A with a prior influenza A virus infection (arrows).

FIG. 5.

Tympanic portion of ET (magnification, ×160). (a) No labeling with BSL II of the normal control cohort 7 days after i.n. inoculation with sterile PBS; (b) weak and focal labeling of BSLII 7 days after i.n. inoculation with PBS in the cohort with a prior influenza A virus infection (arrows); (c) weak and focal labeling with BSL II at the roof and neck after 7 days i.n. inoculation with S. pneumoniae type 6A without a prior influenza A virus infection (arrows); (d) strong labeling with BSL II 7 days after i.n. inoculation of S. pneumoniae type 6A with a prior influenza A virus infection (arrows).

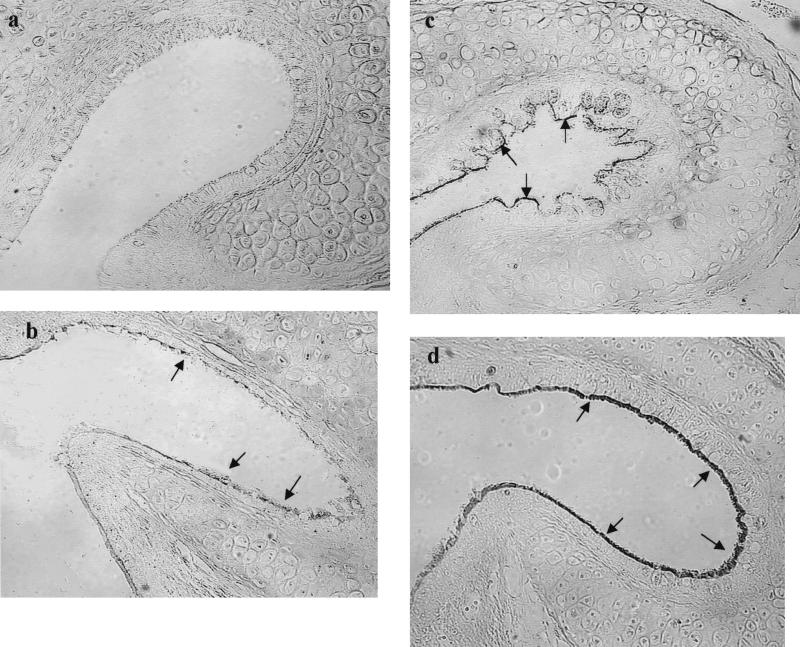

Galactosyl [Gal(β1-4)GlcNAc]-specific lectin (PNA and ECL).

In the control cohort, no labeling with PNA was evident (Fig. 6a). In the cohort with a prior influenza A virus infection, six ETs showed moderate labeling with PNA up to the tympanic portion of the ET on days 1, 3, and 7 after an i.n. challenge of PBS (Fig. 6b). In the S. pneumoniae inoculation cohort, 2 of the 18 ETs examined showed strong labeling. Eight to twelve (ETs) were labeled with weak PNA labeling (Fig. 6c). However, in the dual-pathogen-infected cohort, 12 of 18 (67%) ETs at the pharyngeal portion, 8 of 18 ETs at the mid-portion, and 4 of 18 ETs at the tympanic portion showed strong, intense labeling of PNA (Fig. 6d). These data are comparable to those observed for SWGA and BSL II and suggest the dual pathogen infection induced a significant portion of the surface carbohydrate alterations. For ECL, weak labeling was observed along the surface of the ET in the normal control chinchillas. In the cohort infected with influenza A virus, two of six ETs showed strong ECL labeling and the others showed moderate labeling. In the cohort infected only with S. pneumoniae and in the cohort infected with both pathogens, no significant differences in ECL labeling were observed. The intensity of the enhanced ECL lectin labeling was increased to a moderate level in these two cohorts.

FIG. 6.

Pharyngeal portion of the ET (magnification, ×160). (a) No labeling with PNA of normal control cohort 3 days after inoculation with Sterile PBS; (b) weak to moderate labeling of PNA after 3 days i.n. inoculation of PBS in the cohort with a prior influenza A virus infection (arrows); (c) weak to moderate labeling of PNA after 3 days i.n. inoculation of S. pneumoniae type 6A without a prior influenza A virus infection (arrows); (d) strong staining of PNA after 3 days i.n. inoculation of S. pneumoniae type 6A with a prior influenza A virus infection (arrows).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that in S. pneumoniae-infected OM in the chinchilla, terminal sialic acid residues are removed and GlcNAcβ1-4Gal, a component of the trisaccharide receptor for S. pneumoniae, is exposed in the ET lumen, presumably via the action of neuraminidase (16, 17). Furthermore, our recent report suggests that the products of S. pneumoniae neuraminidase nanA gene have a significant impact on the changes of the carbohydrate moieties on the ET epithelium and may be responsible for the previously reported increased ability of S. pneumoniae parent strain D39 to colonize the nasopharynx and invade the middle ear in the chinchilla OM model (22, 24). Very little is known, however, about the effect of a dual infection with influenza A virus and S. pneumoniae on the carbohydrate surface structure of the ET epithelium in this model. In this study six lectin probes were used to map the alteration of the cell surface carbohydrate structure, and our data demonstrate that a combined influenza A virus and S. pneumoniae infection significantly changes the cell surface carbohydrate structure in the ET beyond that induced by either pathogen alone. The greatly decreased labeling intensity of SNA in the lumen of the ETs in the dual-pathogen-infected cohort, compared to that of the single-pathogen-infected cohort, indicated an increased removal of sialic acid. Moreover, we found that a significantly increased intensity of the labeling with SWGA, BSL II, and PNA of ETs was evident throughout the NP—up to the tympanic portion—in the dual-pathogen-infected cohort. Taken together, the changed patterns of lectin labeling demonstrated that GlcNAc and the subterminal Gal residues (Galβ1-3GalNAc and Galβ1-4GlcNAc) were exposed by the removal of terminal sialic acid, presumably through the action of the neuraminidase from both pathogens. Our data suggest that influenza A virus plays a role in the synergistic alteration of the cell surface carbohydrate structure of the ET beyond that induced by either S. pneumoniae or influenza A virus alone.

The mechanism responsible for the increased labeling induced by the combined infection is not known. Several explanations are plausible. The increased carbohydrate changes induced by the combined infection may simply be additive and reflect an increased concentration of neuraminidase locally. Previous reports have shown that influenza A virus infection increased the lectin labeling of SWGA, PNA, and BSL II in murine NP mucosa and bacterial colonization (13). Moreover, the various changes in lectin reactivity might be a consequence of release of the enzymes from neutrophil degranulation since higher inflammatory cell concentrations were found in the middle ear in the cohort infected by both pathogens. In addition, infection with influenza A virus may result in the expression of new viral proteins on ET epithelium and coincide with the alteration of lectin labeling patterns. The metaplasia of the ET epithelium induced by both influenza A virus and S. pneumoniae might also result in altered glycoconjugate expression at the cell surface. Finally, influenza virus infection might also create a special environment in the ET that possibly promotes upregulation of the S. pneumoniae neuraminidase gene nanA and an increased concentration of neuraminidase in the middle ear.

The increased asialo sites in the epithelium of ETs induced by both influenza A virus and S. pneumoniae may play an important contributory role in encouraging the adherence of S. pneumoniae to newly expressed glycoconjugate as suggested by Plotkowski et al. (20). Glycoconjugates containing the disaccharide units Gal β1-4GlcNAcβ1-3Gal, GalNAcβ1-4Gal, and GalNAcβ1-3Gal have been suggested as pneumococcal cell receptors, which exist on normal resting respiratory epithelial cells, type 2 lung cells, and endothelial cells (3, 9, 26). Once the resting cells are activated by inflammatory cytokines during viral or bacterial infection, the expression of the platelet-activating factor receptor with GlcNAc specificity is induced and results in enhanced pneumococcal adherence (9). The results from our chinchilla OM model demonstrate that the combined influenza A virus-S. pneumoniae infection has a synergistic effect on the exposure of the asialo carbohydrate structure in the ET which might be one of the mechanisms by which virus infection increases accessibility of host receptors for S. pneumoniae and facilitates S. pneumoniae invasion of the middle ear through the ET. Future studies to evaluate whether glycoconjugate or receptor antagonists reduce the risk of S. pneumoniae invading the middle ear could prove to be beneficial in preventing the development of OM.

S. pneumoniae undergoes spontaneous phase variation between a transparent and an opaque colony phenotype. Transparent variants have been shown to be more efficient than the opaque phenotype at colonization of the nasopharynx in an infant rat model of carriage (29). The opaque phenotype, however, is more virulent and is associated with invasive diseases (14). Our recent study indicates that a prior influenza A virus infection impacts the different clearance kinetics for the two phenotypes from the nasopharynx and middle ear (21). In this study, a transition from the transparent form of S. pneumoniae type 6A in the inoculum to the opaque as the predominant phenotype isolated from the MEF was found in the cohort infected with both influenza virus and S. pneumoniae, which was associated with an increased severity and incidence of OM. However, the NP isolates in both the S. pneumoniae-alone cohort and the S. pneumoniae-influenza A virus cohort achieved an equilibrium and 60 to 80% remained predominantly the transparent phenotype for the duration of the experiment.

Intrastrain phase variation and its relevance to the virulence of S. pneumoniae has been previously reported in a mouse model of systemic infection. Pneumococci isolated from mice succumbing after injection with a transparent type 2 or 6A S. pneumoniae, were a more opaque phenotype than the inoculum (14). The increased virulence of the opaque pneumococci is associated with a higher amount of capsular polysaccharide (CPS) and correlates with increased resistance to opsonophagocytosis (15). Furthermore, recent data suggest that the modulation effect of oxygen on CPS expression may be a key factor in allowing for selection of distinct opacity phenotypes in NP colonization for adherence and in bacteremia for escaping opsonic clearance (28). In OM, the less-aerobic microenvironment caused by inflammatory exudate in the middle ear cavity may trigger increased expression of CPS. The significant inflammatory response in the middle ear induced by influenza A virus and S. pneumoniae, as we found in this study, may create the microenvironment for selection of the opaque forms of S. pneumoniae. We cannot determine from the present study whether the predominance of the opaque phenotype in the middle ear is the result of actual phase switching or selection of the opaque organisms due to their innate resistance to phagocytosis. Unpublished data from our laboratory indicates that a higher inoculum concentration of S. pneumoniae in an S. pneumoniae-only cohort results in higher concentrations of inflammatory cells but not a higher incidence of the opaque phenotype, suggesting that influenza A virus plays a role in the net increase in the incidence of the opaque phenotype. Thus, our data suggest a possible role of influenza A virus infection in the intrastrain opacity phase variation of S. pneumoniae during the development of OM.

In summary, our results indicate that influenza A virus and S. pneumoniae infection has the synergistic effect on the exposure of asialo carbohydrate moieties in the ET which might serve as an additional mechanism by which virus infection increases the accessibility of host receptors for S. pneumoniae and facilitate S. pneumoniae invasion of the middle ear through the ET. The selection of the opaque form of S. pneumoniae subsequent to an influenza virus infection should be considered as another factor in the pathogenesis of experimental OM.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by NIDCD/NIH grant R01 DC3105-06.

We thank Kathy Holloway for manuscript preparation.

Editor: E. I. Tuomanen

REFERENCES

- 1.Abramson, J. S., G. S. Giebink, and P. G. Quie. 1982. Influenza A virus-induced polymorphonuclear leukocyte dysfunction in the pathogenesis of experimental pneumococcal otitis media. Infect. Immun. 36:289-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abramson, J. S., G. S. Giebink, E. L. Mills, and P. G. Quie. 1981. Polymorphonuclear leukocyte dysfunction during influenza virus infection in chinchillas. J. Infect. Dis. 143:836-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson, B., J. Dahmen, T. Frejd, H. Leffler, G. Magnusson, G. Noori, and C. S. Eden. 1983. Identification of an active disaccharide unit of a glycoconjugate receptor for pneumococci attaching to human pharyngeal epithelial cells. J. Exp. Med. 158:559-570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchman, C. A., W. J. Doyle, D. P. Skoner, J. C. Post, C. M. Alper, J. T. Seroky, K. Anderson, R. A. Preston, F. G. Hayden, P. Fireman, and G. D. Ehrlich. 1995. Influenza A virus-induced acute otitis media. J. Infect. Dis. 172:1348-1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chonmaitree, T., J. A. Patel, M. A. Lett-Brown, T. Uchida, R. Garofalo, M. J. Owen, and V. M. Howie. 1994. Virus and bacteria enhance histamine production in middle ear fluids of children with acute otitis media. J. Infect. Dis. 169:1265-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chonmaitree, T., and T. Heikkinen. 1997. Role of viruses in middle-ear disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 830:143-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung, M. H., S. R. Griffith, K. H. Park, D. J. Lim, and and T. F. DeMaria. 1993. Cytological and histological changes in the middle ear after inoculation of influenza A virus. Acta Otolaryngol. 113:81-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cundell, D. R., J. N. Weiser, J. Shen, A. Young, and E. I. Tuomanen. 1995. Relationship between colonial morphology and adherence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 63:757-761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cundell, D. R., N. P. Gerard, C. Gerard, I. Idanpaan-Heikkila, and E. I. Tuomanen. 1995. Streptococcus pneumoniae anchor to activated human cells by the receptor for platelet-activating factor. Nature 377:435-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giebink, G. S., I. K. Berzins, S. C. Marker, and G. Schiffman. 1980. Experimental otitis media after nasal inoculation of Streptococcus pneumoniae and influenza A virus in chinchillas. Infect. Immun. 30:445-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hament, J. M., J. L. Kimpen, A. Fleer, and T. F. Wolfs. 1999. Respiratory viral infection predisposing for bacterial disease: a concise review. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 26:189-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heikkinen, T. 2001. The role of respiratory viruses in otitis media. Vaccine 19:S51-S55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirano, T., Y. Kurono, I. Ichimiya, M. Suzuki, and G. Mogi. 1999. Effects of influenza A virus on lectin-binding patterns in murine nasopharyngeal mucosa and on bacterial colonization. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 121:616-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim, J. O., and J. Weiser. 1998. Association of intrastrain phase variation phase variation in quantity of capsular polysaccharide and teichoic acid with virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 177:368-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim, J. O., S. Romero-Steiner, U. B. Sorensen, J. Blom, M. Carvalho, S. Barnard, G. Carlone, and J. N. Weiser. 1999. Relationship between cell surface carbohydrates and intrastrain variation on opsonophagocytosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 67:2327-2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linder, T. E., D. J. Lim, and T. F. DeMaria. 1992. Changes in the structure of the cell surface carbohydrates of the chinchilla tubotympanum following Streptococcus pneumoniae-induced otitis media. Microb. Pathog. 13:293-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linder, T. E., R.L Daniels, D. J. Lim, and T. F. DeMaria. 1994. Effect of intranasal inoculation of Streptococcus pneumoniae on the structure of the surface carbohydrates of the chinchilla eustachian tube and middle ear mucosa. Microb. Pathog. 16:435-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohashi, Y., Y. Nakai, Y. Esaki, Y. Ohno, Y. Sugiura, and H. Okamoto. 1991. Influenza A virus-induced otitis media and mucociliary dysfunction in the guinea pig. Acta Otolaryngol. 486:135-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park, K., L. O. Bakaletz, J. M. Coticchia, and D. J. Lim. 1993. Effect of influenza A virus on ciliary activity and dye transport function in the chinchilla eustachian tube. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 102:551-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plotkowski, M. C., E. Puchelle, G. Beck, J. Jacquot, and C. Hannoun. 1986. Adherence of type I Streptococcus pneumoniae to tracheal epithelium of mice infected with influenza A/PR8 virus. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 134:1040-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tong, H. H., J. N. Weiser, M. A. James, and T. F. DeMaria. 2001. Effect of influenza A virus on nasopharyngeal colonization and otitis media induced by transparent or opaque phenotype variants of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the chinchilla model. Infect. Immun. 69:602-606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong, H. H., L. E. Blue, M. A. James, and T. F. DeMaria. 2000. Evaluation of the virulence of a Streptococcus pneumoniae neuraminidase-deficient mutant in nasopharyngeal colonization and development of otitis media in the chinchilla model. Infect. Immun. 68:921-924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tong, H. H., L. M. Fisher, G. M. Kosunick, and T. F. DeMaria. 2000. Effect of adenovirus type 1 and influenza A virus on Streptococcus pneumoniae nasopharyngeal colonization and otitis media in the chinchilla. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 109:1021-1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tong, H. H., M. James, I. Grants, X. Liu, G. Shi, and T. F. DeMaria. 2001. Comparison of structural changes of cell surface carbohydrates in the eustachian tube epithelium of chinchillas infected with a Streptococcus pneumoniae neuraminidase-deficient mutant or its isogenic parent strain. Microb. Pathog. 31:309-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tong, H. H., M. A. McIver, L. M. Fisher, and T. F. DeMaria. 1999. Effect of lacto-N-neotetraose, asialoganglioside-GM1 and neuraminidase on adherence of otitis media-associated serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae to chinchilla tracheal epithelium. Microb. Pathog. 26:111-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tuomanen, E. I. 1997. The biology of pneumococcal infection. Pediatr. Res. 42:253-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wadowsky, R. M., S. M. Mietzner, D. P. Skoner, W. J. Doyle, and P. Fireman. 1995. Effect of experimental influenza A virus infection on isolation of Streptococcus pneumoniae and other aerobic bacteria from the oropharynges of allergic and non-allergic adult subjects. Infect. Immun. 63:1153-1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiser, J. N., D. Bae, H. Epino, S. B. Gordon, M. Kapoor, L. A. Zenewicz, and M. Shchepetov. 2001. Changes in availability of oxygen accentuate differences in capsular polysaccharide expression by phenotypic variants and clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 69:5330-5439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiser, J. N., R. Austrian, P. K. Sreenivasan, and H. R. Masure. 1994. Phase variation in pneumococcal opacity: relationship between colonial morphology and nasopharyngeal colonization. Infect. Immun. 62:2582-2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]