Abstract

A novel Mycobacterium leprae lipoprotein LpK (accession no. ML0603) was identified from the genomic database. The 1,116-bp open reading frame encodes a 371-amino-acid precursor protein with an N-terminal signal sequence and a consensus motif for lipid conjugation. Expression of the protein, LpK, in Escherichia coli revealed a 33-kDa protein, and metabolic labeling experiments and globomycin treatment proved that the protein was lipidated. Fractionation of M. leprae demonstrated that this lipoprotein was a membrane protein of M. leprae. The purified lipoprotein was found to induce production of interleukin-12 in human peripheral blood monocytes. The studies imply that M. leprae LpK is involved in protective immunity against leprosy and may be a candidate for vaccine design.

The aggressive global implementation of effective chemotherapy has resulted in a diminution of leprosy cases from ca. 10 million in 1985 to ca. 800,000 today (32, 33). However, the World Heath Organization (WHO) elimination goal has not yet been achieved, and there is no evidence as yet of a reduction in the number of new cases, in that, according to a WHO epidemiological survey, more than 650,000 new cases were detected globally at the beginning of 2000 (33). The situation implies that there is a need to develop new vaccines and immunotherapeutic tools to control the disease. Moreover, there is increased concern about the disease due to the emergence of drug-resistant bacilli (16), complications due to severe reactions, and peripheral nerve injury due to the tropism of the bacilli to invade Schwann cells (13, 20, 24).

Mycobacterial entities involved in the sequelae of immunoregulatory events are not clear as yet. Recently, lipoproteins are reported to influence both innate and adaptive immunity (12, 21). Since the process of lipid modification in murein lipoproteins occur only in prokaryotes (34), these proteins could be assumed to be useful in the regulation of bacterial infection.

Bacterial lipoproteins containing N-acyl diglyceride-cysteine residues, flanked by characteristic amino acids motif that are required for posttranslational processing via the signal peptidase II (27, 34), have been extensively studied in gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. The only two well-known mycobacterial lipoproteins are the 19- and 38-kDa lipoproteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (19, 21, 35). Another membrane located lipoprotein, reported by Sjosted et al. (29, 30), is a 17-kDa Francisella tularensis lipoprotein that was found to be T-cell stimulatory. Borrelia burgdorferi and Treponema pallidum, the etiological agents of Lyme disease and syphilis, respectively, are known to possess abundant lipoproteins (23), which act as major antagonists with the ability to influence both innate and adaptive immune responses during infection (12). These lipoproteins are therefore presumed to be involved in the host responses, inducing interleukin-12 (IL-12) from the host cells. Since IL-12 has T-cell stimulatory properties, which in turn elicit the production of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and facilitate the development of Th1 cells (28, 31, 36), these lipoproteins may be involved in the induction of cellular and humoral responses to mycobacteria, thereby contributing to the development of protective immunity. Therefore, identification of lipoproteins in M. leprae seems inevitable, especially in terms of host stimulatory responses and thereby to develop new vaccines against leprosy. In the present study, we report the identification, expression, and purification of a novel M. leprae lipoprotein that has IL-12-inducing capability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

E. coli DH5α strain (Toyobo, Tokyo, Japan) was used for all cloning and recombinant expression experiments. The plasmids used for the expression in E. coli were pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega, Madison, Wis.), pET23a vector (Novagen, Madison, Wis.), and pGFPuv (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.). Clones were selected on Luria-Bertani medium agar plates (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl, 1.5% agar) or broth supplemented with ampicillin at 100 μg/ml. All other chemicals were purchased from Wako Chemicals (Richmond, Va.), Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.), or Amersham-Pharmacia (Piscataway, N.J.).

Cloning and sequencing of the lpk gene.

Based on the database of M. leprae genomic sequence (2) at the Sanger Center (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/projects/M.leprae), we selected the genes coding for the proteins having predictable lipid modification site. The selected sequences were characterized by using the BLASTN program at National Center for Biotechnology Information site. The analysis of amino acid alignments was performed by using the software GENETYX-MAC. For the cloning of the lpk gene (accession no. ML0603), the sense primer 5′-ACATGCATGCCCTGGTGTTGGTCCTGTGG-3′ having the SphI site and the antisense primer 5′-CGGAATTCTTAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGTCGGCTCCCATCGGCG-3′ having the EcoRI site were synthesized, and the DNA of interest amplified by PCR by taking the genomic DNA from M. leprae (Thai-53 strain) as a template for PCR. The gene was first cloned into pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega) and further inserted into the expression vectors pGFPuv and pET23a. All other genetic manipulations were done according to established cloning techniques (26). Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.), Takara Shuzo (Shiga, Japan), or Toyobo Co. (Osaka, Japan) and used according to the manufacturer's specifications. For DNA sequencing, plasmid DNA samples were purified by using Qiagen MiniPrep Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). DNA sequence analysis was performed on ABI Prism Genetic Analyzer (PE Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) by using dideoxy dye termination PCR method.

Detection of the expressed proteins and protein purification.

E. coli transformants were lysed with BugBuster protein extraction reagent (Novagen) and run on a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-12% polyacrylamide gel (15). The resolved proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.). The proteins were then detected by using either green fluorescent protein (GFP) peptide antibody (Clontech) or Penta-His monoclonal antibody (Qiagen), and developed with BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate)-nitroblue tetrazolium. Histidine-tagged proteins were purified by using His-Bind resin and buffer kit (Novagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions with modifications. In order to eliminate other protein impurities and endotoxins, the lysed samples were first bound to the resin and then washed with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 60% isopropanol in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) alternatively at least three times (7). The bound protein was then eluted with buffer containing 60 mM imidazole. After SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, the proteins were stained either by Silver Stain Daiichi (Dai-ichi Pure Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan) or Coomassie brilliant blue stain.

[14C]glycerol radiolabeling of LpK.

We intrinsically labeled 5-ml E. coli cultures in the log phase of growth by the addition of 20 μCi of [14C]glycerol (specific activity, 142.7 mCi/mmol; NEN Life Science Products Boston, Mass.)/ml, followed by further incubation at 37°C for a given period or until the cells reached the stationary phase of growth. Cells were then centrifuged and washed in phosphate-buffered saline, lysed in BugBuster (Novagen) and the soluble protein was immunoprecipitated by using His-Bind resin. The protein was run on an SDS-12% polyacrylamide gel, and the gel was vacuum dried. The autoradiography was performed by using Fuji imaging plate BAS-TR2040 and analyzed by Fuji Bio-Imaging Analyzer IPR-1000 (Fuji Photo Film Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Globomycin treatment of LpK.

Globomycin (a gift from Sankyo Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan) dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma) was added to an exponentially growing culture of E. coli expressing LpK to a final concentration of 50 μg/ml. After various periods of incubation (1, 3, and 5 h), the cells were centrifuged and then analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Control cultures contained no globomycin.

Western blot analysis.

Three major subcellular fractions of M. leprae, namely, cell wall, cytoplasmic membrane, and cytosol, were separated by centrifugation as follows: a BC-20 homogenizer (Central Scientific Commerce, Tokyo, Japan) was used to disrupt the hard cell wall of mycobacteria. The mycobacterial suspension at a concentration of 109/ml was mixed with zirconium beads at a ratio of ca. 1:1 (vol/vol) and then processed at 1,500 × g for 90 s three to four times with 10-min interruptions for cooling. The suspension was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min to remove the cell wall fractions. The supernatant was then ultracentrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h. The resulting supernatant was taken as the cytosolic fraction; the pellet was washed twice, resuspended in PBS, and taken as the membrane fraction. The protein concentration of each fraction was determined by using Bio-Rad's protein assay kit. Equivalent protein amounts (3 μg/well) were separated on 13% polyacrylamide gels under reducing conditions. Antibodies raised in rabbit against the recombinant lipoprotein LpK were used to probe the native protein of M. leprae.

Measurement of IL-12 production by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy individuals were isolated on Ficoll-Paque Plus (Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) and cultured for 1 h in 10-cm dishes. The adherent cells were then detached and cultured in 96-well plates (105 cells/well). Purified lipoproteins at concentration of 0.5 μg/ml in RPMI (Sigma) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) were added in triplicate to the mononuclear cells. The amount of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the purified lipoprotein was measured quantitatively with a Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Whittaker Bioproducts, Walkersville, Md.) and found to be <5 pg per μg of protein, an amount that did not stimulate IL-12 by itself. LPS (E. coli O111:B4; Difco laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) at 10 ng/ml was used as an indicator of the IL-12-inducing ability of monocytes. Polymyxin was added to some of the cultures at 10 μg/ml. After 20 to 24 h, the culture supernatants were collected and assayed for human IL-12 p40 by using OptEIA Set (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.).

RESULTS

Cloning and sequence analysis of the lpk gene.

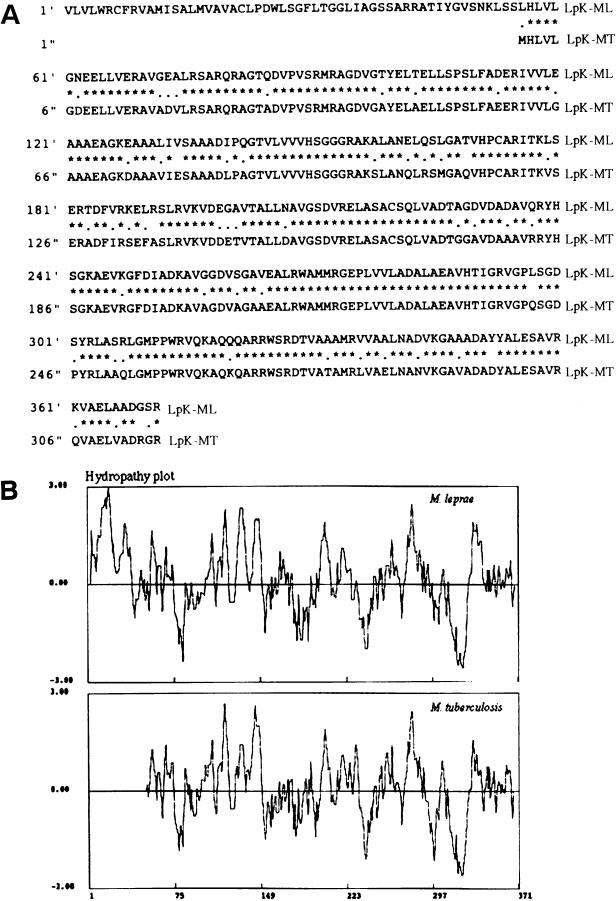

The genomic sequence analyses of the database of M. leprae revealed several genes having the consensus sequence for lipid modification. Of much interest was a gene lpk (accession no. ML0603), which had no lipid modification motif in its corresponding M. tuberculosis homologue (Rv2413c). The nucleotide sequence showed a predicted start codon at GTG, and the N-terminal sequence revealed that it codes for amino acids that resemble a signal peptide. The consensus amino acid sequence for lipid modification is MISALMVAVAC. The cysteine residue at position 22 could be expected to be modified by subsequent addition of the characteristic diacyl glycerol and N-terminal linked fatty acid of bacterial lipoproteins. A BLAST search of the genome database revealed an 80% homologous gene in M. tuberculosis, the translated amino acid alignment of which is shown (Fig. 1A). The hydropathy plot of the protein LpK revealed that the N-terminal sequence represents a signal sequence (14), and the hydropathic plot comparison showed that the N-terminal hydrophobic counterpart of LpK was not present in the M. tuberculosis homologue (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

(A) Comparison of the deduced amino acid of M. leprae lpk (LpK-ML) to its homologue in M. tuberculosis (LpK-MT). The upper amino acid sequence is that of M. leprae, and the lower sequence is that of M. tuberculosis. Identical amino acids at each position are marked by asterisks, conservative substitutions are indicated by one dot, and nonconservative substitutions are indicated by a space. (B) Comparison of the hydropathy plot of M. leprae lpk gene product with its M. tuberculosis homologue by the algorithm of Kyte and Doolittle. Positive regions denote regions of relative hydrophobicity.

Expression of the gene lpk in E. coli and its purification.

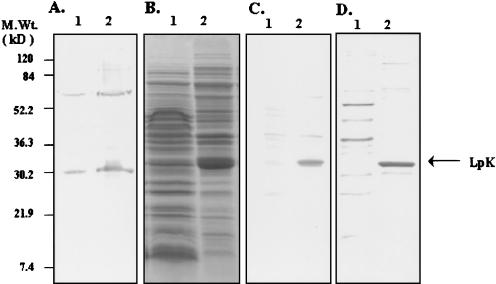

Since it is not feasible to obtain adequate amount of protein from M. leprae for analysis, attempts have been made to express M. leprae proteins in different expression systems. The expression of these lipoproteins in E. coli by using the T7 expression system (IMPACT T7) seemed to be either toxic to the host cells, or the expressed protein formed inclusion bodies. When LpK was fused to the GFP gene with the pGFPuv (Clontech) plasmid, the protein was successfully expressed. The expression plasmid pGFP-lpk contained the lpk gene fused at the N terminus of gfp gene under the lac promoter. When this plasmid (pGFP-lpk) was transformed into E. coli, the blot (Fig. 2A) showed two bands at 30 and 65 kDa with anti-GFP antibodies. The upper band at 65 kDa is the fusion protein, and the lower one (30 kDa), that of GFP alone, probably appeared due to the cleavage of the thrombin site between GFP and LpK with endogeneous protease. Repeated attempts to purify this protein by using anti-GFP antibodies were not successful. Therefore, we modified this plasmid by introducing the histidine tag-coding gene at the C-terminal region of lpk and deleting the GFP coding gene. When the resulting expression plasmid pG-lpk was transformed into DH5α, the protein LpK was expressed and found to be ca. 33 kDa, as seen in a Coomassie blue-stained gel (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, to prove the identity of the 33-kDa protein immunologically, the protein blotted polyvinylidene difluoride membrane was reacted with Penta-His antibody, and the band was observed at the same position (Fig. 2C). For purification purposes, we used the His-Bind kit and, to reduce the amount of endotoxin contamination, we modified the procedure as described in Materials and Methods. Elution of the protein with 60 mM imidazole resulted in the purified LpK protein. Figure 2D shows the silver staining of the purified product. It indicates that LpK was finally expressed and purified to near homogeneity.

FIG. 2.

Expression and purification of the LpK and its fusion products. (A) Western blot with anti-GFP antibody without (lanes 1) and with (lanes 2) IPTG induction of pGFP-lpk-transformed E. coli. (B) Coomassie staining with mock-transformed (lanes 1) and pG-lpk-transformed (lanes 2) E. coli. (C) Western blot of the same protein as that for panel B, using a monoclonal anti-His antibody. (D) Silver staining of the purified protein LpK, a column pass through (lanes 1) and proteins eluted with imidazole (lanes 2).

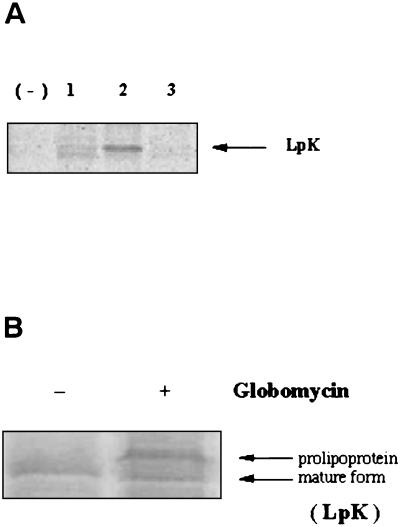

Evidence that LpK protein is lipidated.

To confirm the presence of the predicted lipid modification of the LpK protein, the protein was radiolabeled with [14C]glycerol and immunoprecipitated with His-Bind resin. The protein at the predicted molecular mass of 33 kDa was found to be labeled after a 5-h incubation period after the addition of radioactive glycerol and, at 3 h, only partial formation of the mature lipoprotein was observed (Fig. 3A). To provide more evidence that the protein is lipidated, LpK-expressing cells were treated with the antibiotic globomycin, which specifically inhibits cleavage of lipoprotein signal peptides by peptidase II (5, 11). As seen in Fig. 3B, a band with a higher molecular mass than that of the mature form of LpK was observed; this finding is attributable to the accumulation of the prolipoprotein form of LpK.

FIG. 3.

(A) [14C]glycerol radiolabeling of the expressed protein LpK. E. coli tranformants of lpk were cultured up to an optical density of 0.5; incubated with [14C]glycerol for 1 h (lanes 1), 2 h (lane 2), or 5 h (lane 3); and then immunoprecipitated. The proteins were run on an SDS-12% polyacrylamide gel, and then autoradiography was performed. (B) Globomycin inhibits the processing of the prolipoprotein to lipoprotein. E. coli were grown in the presence (+) or absence (−) of globomycin to stationary phase. Lysates were run on gel and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue.

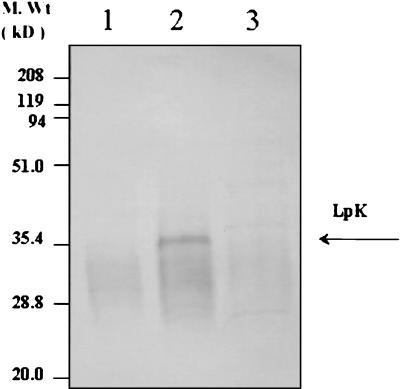

Presence of native LpK in M. leprae.

Fractionation of M. leprae proteins into three fractions, namely, cell wall, cytosolic, and membrane, revealed that the membrane fraction reacted to the polyclonal antibody raised against LpK (Fig. 4). In contrast, whole-cell fractions of M. avium or M. bovis BCG did not show any reactivity against the antibody (data not shown). The result suggests that this lipoprotein may be unique to M. leprae.

FIG. 4.

Presence of the native protein LpK in M. leprae grown in vivo. M. leprae purified from armadillo liver was fractionated into cell wall (lane 1), cell membrane (lane 2), and cytosolic (lane 3) fractions. A Western blot with polyclonal antibody raised against LpK revealed the presence of LpK in the membrane preparation of M. leprae.

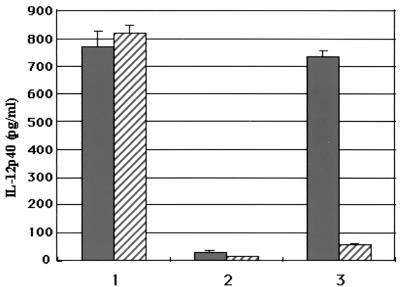

IL-12 production in monocytes by LpK.

IL-12 is one of the cytokines induced by mycobacteria and its products and has a function of biasing CD4+ T cells toward Th1 differentiation that is closely associated with host defense against mycobacterial infection. IL-12 is also required to eliminate the intracellular pathogen (6, 8, 28). To examine the functional relevance of the protein LpK, we measured IL-12 production by peripheral blood monocytes when stimulated with LpK. There was a significant amount of IL-12 production in response to LpK (Fig. 5) in a dose-dependent manner. The figure shows that ca. 800 pg/ml of IL-12 p40 is induced by 0.5 μg of the protein/ml. However, another 39-kDa lipoprotein (a product of accession no. ML1699) purified from inclusion bodies (data not shown) did not show any such production of cytokine. In order to exclude the possibility of IL-12 production by the presence of any contaminating endotoxin in the purified extract, we added polymyxin B (4) to the culture medium, along with the lipoprotein. LpK did not show any significant decrease in IL-12 production in the presence of polymyxin, whereas that of LPS did (Fig. 5). The results indicate that LpK can indeed induce IL-12 production in human monocytes.

FIG. 5.

M. leprae LpK induces IL-12 p40 from human blood monocytes. Peripheral blood monocytes were isolated, and the ability of LpK to stimulate IL-12 p40 was measured as described in Materials and Methods. IL-12 p40 cytokine induction was then assessed, with (▨) or without ( ) polymyxin B, with LpK (columns 1), LpC (ML1699) (columns 2), and LPS (columns 3). lpc was identified from the database as a putative lipoprotein coding gene that was expressed and purified from inclusion bodies as a 39-kDa protein in E. coli. Values are expressed as the mean ± the standard deviation performed in triplicate.

) polymyxin B, with LpK (columns 1), LpC (ML1699) (columns 2), and LPS (columns 3). lpc was identified from the database as a putative lipoprotein coding gene that was expressed and purified from inclusion bodies as a 39-kDa protein in E. coli. Values are expressed as the mean ± the standard deviation performed in triplicate.

DISCUSSION

To date, relatively few lipoproteins in Mycobacterium species have been described. In M. tuberculosis, the 19-kDa antigen is the most extensively studied lipoprotein (22, 25, 35), but no lipoproteins have been identified in M. leprae. The M. tuberculosis genome database (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/M_tuberculosis/) revealed that there are about a 100 putative lipoprotein coding genes, but only about 30 genes have been identified in the M. leprae genome (2), and almost half of the genes identified are pseudogenes.

In the present study, we identified a few genes in M. leprae that may be lipid modified by examining the deduced amino acid sequence of the gene products for the presence of a signal peptide with a cleavage site analogous to the consensus sequence for prolipoprotein modification. One of the more interesting candidates is the gene lpk (accession no. ML0603). The N-terminal residues of LpK showed typical features of a signal peptide with a C-terminal consensus sequence for the lipid modification. A sequence homologue of lpk was identified in the M. tuberculosis genome database by using the BLASTN search tool. M. tuberculosis Rv 2413c (EMBL no. AL123456, 316 amino acids) shows 83.5% identity in the 316-amino-acid overlap. However, the homologue has no consensus sequence for lipid modification. The fact that the lipid consensus sequence was missing is quite surprising since many of the M. leprae genes compared to those of M. tuberculosis are pseudogenes, as analyzed from the gene databases (2). This fact may indicate that this lipoprotein may have a significant role in M. leprae, one specifically related to the unique features of the organism, such as proclivity for Schwann cell invasion or the development of reactions. Therefore, we have cloned the gene lpk in E. coli expression systems. Expression with the T7 promoter (pET system) did not produce detectable amounts of protein, and IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) induction of the protein resulted in toxicity for the host cell. Therefore, we used the weaker lac promoter for expression. In this system, the protein LpK was fused to GFP. Blotting with anti-GFP monoclonal antibody revealed that the protein could be expressed in E. coli from a weak lac promoter. However, purification with anti-GFP-Sepharose was not easy; thus, we reconstructed the expression vector to contain the protein fused to the histidine tag instead of to GFP. The protein was purified to apparent homogeneity by using the His-Bind resin (Fig. 2D). The resin-bound protein could be eluted with a low concentration of 60 mM imidazole. The low-affinity binding may be due to interference due to some posttranslational modification of the protein or its hydrophobic nature. The basic lipoprotein nature of LpK was verified experimentally. Metabolic labeling of the bacterial protein with radioactive glycerol provided presumptive evidence of a covalent linkage of lipid to LpK. Accumulation of the apparent precursor form of LpK in cells treated with globomycin, a specific inhibitor of signal peptidase II, also indicated that LpK was lipid modified, although it still remains to be examined whether LpK is lipidated in in vivo-growing M. leprae.

In order to search for the native LpK in M. leprae, we prepared the rabbit polyclonal antibody to LpK. When applied to subcellular fractions obtained from armadillo-derived M. leprae (10), it was clear that LpK was present in the membrane fraction (Fig. 4), in the same fraction as were bacterioferritin and major membrane protein I (10), which are reliable protein markers of the membrane fraction of M. leprae. Since membrane-associated lipoproteins have been identified as major antigens in M. tuberculosis, T. pallidum, and Mycoplasma hyorhinis (1, 23, 35), it may be predictable that LpK lipoprotein is one of the antigens of leprosy. Studies are under way to evaluate the antigenicity of LpK and also to analyze whether LpK is exposed on the surface of M. leprae.

Murine experiments with infectious pathogens, indicate that IL-12 plays an important role in inititation and regulation of the Th1-like responses (6, 17). In vitro experiments with M. tuberculosis suggested that IL-12 is induced rapidly after infection (8, 9, 36), and IL-12 is crucial for the development of protective immunity against tuberculosis in mice (3). We therefore examined whether IL-12 was inducible by LpK in human monocytes. Although IL-12 production by whole M. leprae was not as high (data not shown), LpK lipoprotein induced IL-12 at a significantly high level, a level that could be maintained even in the presence of polymyxin (Fig. 5). The IL-12 production was observed almost in all 12 peripheral blood donors examined, in an antigen dose-dependent manner (data not shown). For purposes of comparison, another M. leprae putative lipoprotein (gene product of accession no. ML1699, annotated as lpc) was expressed in E. coli in the form of inclusion bodies. The purified protein (39 kDa) did not induce any significant amount of IL-12 in human monocytes. The reason for the noninducing capability of the purified 39-kDa protein may be the lack of lipidified region, although the exact reason remains unclear. IL-12 production in mycobacterial diseases is known to contribute to antimycobacterial defenses (4, 18, 28) by triggering IFN-γ, which, in turn, can reduce, for example, the bacillary load in lepromatous leprosy patients (36). Therefore, from the cytokine-inducing nature of LpK, we can anticipate that the lipoprotein may have the potential to contribute to the host defenses against leprosy.

In conclusion, LpK, a lipoprotein apparently unique to M. leprae, was found to induce the production of IL-12, which may indicate a significant role in the induction of cellular responses leading to the development of protective immunity against the intracellular organism. Although the participation of LpK in the pathogenesis of leprosy has yet to be evaluated, ongoing studies are being conducted to evaluate its immunogenic role in leprosy and its possible use in vaccine development.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to V. D. Vissa, J. S. Spencer, and J. T. Belisle from Colorado State University for vital discussions and suggestions and to Sankyo Chemical Co., Tokyo, for the generous gift of globomycin. We thank M. Hein for the preparation of the manuscript. We also thank the Japanese Red Cross Society for providing us with human sera.

This work was supported in part by grants from Health Science Research Grants-Research on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases; from the Japan Health Sciences Foundation, the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare, Japan; and from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (contract NO1 AI-55262).

Editor: D. L. Burns

REFERENCES

- 1.Bricker, T. M., M. J. Boyer, J. Keith, R. Watson-McKown, and K. S. Wise. 1998. Association of lipids with integral membrane surface proteins of Mycoplasma hyorhinis. Infect. Immun. 56:295-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cole, S. T., K. Eiglmeier, J. Parkhill, K. D. James, N. R. Thomson, P. R. Wheeler, N. Honore, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, K. Mungall, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. M. Davies, K. Devlin, S. Duthoy, T. Feltwell, A. Fraser, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, C. Lacroix, J. Maclean, S. Moule, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, M. A. Quail, M. A. Rajandream, K. M. Rutherford, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, S. Simon, M. Simmonds, J. Skelton, R. Squares, S. Squares, K. Stevens, K. Taylor, S. Whitehead, J. R. Woodward, and B. G. Barrell. 2001. Massive gene decay in the leprosy bacillus. Nature 409:1007-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper, A. M., J. Magram, J. Ferrante, and I. M. Orme. 1997. Interleukin 12 (IL-12) is crucial to the development of protective immunity in mice intravenously infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 186:39-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper, A. M., A. D. Roberts, E. R. Rhoades, J. E. Callahan, D. M. Getzy, and I. M. Orme. 1995. The role of interleukin-12 in acquired immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Immunology 84:423-432. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dev, I. K., R. J. Harvey, and P. H. Ray. 1985. Inhibition of prolipoprotein signal peptidase by globomycin. J. Biol. Chem. 260:5891-5894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dockrell, H. M., S. K. Young, K. Britton, P. J. Brennan, B. Rivoire, M. F. Waters, S. B. Lucas, F. Shahid, M. Dojki, T. J. Chiang, Q. Ehsan, K. P. McAdam, and R. Hussain. 1996. Induction of Th1 cytokine responses by mycobacterial antigens in leprosy. Infect. Immun. 64:4385-4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franken, K. L., H. S. Hiemstra, K. E. van Meijgaarden, Y. Subronto, J. den Hartigh, T. H. Ottenhoff, and J. W. Drijfhout. 2000. Purification of His-tagged proteins by immobilized chelate affinity chromatography: the benefits from the use of organic solvent. Protein Expr. Purif. 18:95-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fulton, S. A., J. M. Johnsen, S. F. Wolf, D. S. Sieburth, and W. H. Boom. 1996. Interleukin-12 production by human monocytes infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis: role of phagocytosis. Infect. Immun. 64:2523-2531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gately, M. K., and M. J. Brunda. 1995. Interleukin-12: a pivotal regulator of cell-mediated immunity. Cancer Treat. Res. 80:341-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter, S. W., B. Rivoire, V. Mehra, B. R. Bloom, and P. J. Brennan. 1990. The major native proteins of the leprosy bacillus. J. Biol. Chem. 265:14065-14068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussain, M., S. Ichihara, and S. Mizushima. 1980. Accumulation of glyceride-containing precursor of the outer membrane lipoprotein in the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli treated with globomycin. J. Biol. Chem. 255:3707-3712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Infante-Duarte, C., and T. Kamradt. 1997. Lipopeptides of Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface proteins induce Th1 phenotype development in alphabeta T-cell receptor transgenic mice. Infect. Immun. 65:4094-4099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Job, C. K. 1989. Nerve damage in leprosy. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 57:532-539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kyte, J., and R. F. Doolittle. 1982. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 157:105-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 178:1274-1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maeda, S., M. Matsuoka, N. Nakata, M. Kai, Y. Maeda, K. Hashimoto, H. Kimura, K. Kobayashi, and Y. Kashiwabara. 2001. Multidrug resistant Mycobacterium leprae from patients with leprosy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3635-3639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manetti, R., F. Gerosa, M. G. Giudizi, R. Biagiotti, P. Parronchi, M. P. Piccinni, S. Sampognaro, E. Maggi, S. Romagnani, G. Trinchieri, et al. 1992. Cloning and expression of murine IL-12. J. Exp. Med. 148:3433-3440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Modlin, R. L., and P. F. Barnes. 1995. IL-12 and the human immune response to mycobacteria. Res. Immunol. 146:526-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohagheghpour, N., D. Gammon, L. M. Kawamura, A. van Vollenhoven, C. J. Benike, and E. G. Engleman. 1998. CTL response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis: identification of an immunogenic epitope in the 19-kDa lipoprotein. J. Immunol. 161:2400-2406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ng, V., G. Zanazzi, R. Timpl, J. F. Talts, J. L. Salzer, P. J. Brennan, and A. Rambukkana. 2000. Role of the cell wall phenolic glycolipid-1 in the peripheral nerve predilection of Mycobacterium leprae. Cell 103:511-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oftung, F., H. G. Wiker, A. Deggerdal, and A. S. Mustafa. 1997. A novel mycobacterial antigen relevant to cellular immunity belongs to a family of secreted lipoproteins. Scand. J. Immunol. 46:445-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prestidge, R. L., P. M. Grandison, D. W. Chuk, R. J. Booth, and J. D. Watson. 1995. Production of the 19-kDa antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Escherichia coli and its purification. Gene 164:129-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radolf, J. D., L. L. Arndt, D. R. Akins, L. L. Curetty, M. E. Levi, Y. Shen, L. S. Davis, and M. V. Norgard. 1995. Treponema pallidum and Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins and synthetic lipopeptides activate monocytes/macrophages. J. Immunol. 154:2866-2877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rambukkana, A., J. L. Salzer, P. D. Yurchenco, and E. I. Tuomanen. 1997. Neural targeting of Mycobacterium leprae mediated by the G domain of the laminin-α2 chain. Cell 88:811-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rees, A. D., A. Faith, E. Roman, J. Ivanyi, K. H. Wiesmuller, and C. Moreno. 1993. The effect of lipoylation on CD4 T-cell recognition of the 19,000 MW Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen. Immunology 80:407-414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook, J., and S. A. Russell. 2002. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 27.Sankaran, K., and H. C. Wu. 1994. Lipid modification of bacterial prolipoprotein. Transfer of diacylglyceryl moiety from phosphatidylglycerol. J. Biol. Chem. 269:19701-19706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sieling, P. A., X. H. Wang, M. K. Gately, J. L. Oliveros, T. McHugh, P. F. Barnes, S. F. Wolf, L. Golkar, M. Yamamura, Y. Yogi, et al. 1994. IL-12 regulates T helper type 1 cytokine responses in human infectious disease. J. Immunol. 153:3639-3647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sjostedt, A., G. Sandstrom, and A. Tarnvik. 1992. Humoral and cell-mediated immunity in mice to a 17-kilodalton lipoprotein of Francisella tularensis expressed by Salmonella typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 60:2855-2862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sjostedt, A., A. Tarnvik, and G. Sandstrom. 1991. The T-cell-stimulating 17-kilodalton protein of Francisella tularensis LVS is a lipoprotein. Infect. Immun. 59:3163-3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vordemeier, H. M., D. P. Harris, E. Roman, R. Lathigra, C. Moreno, and J. Ivanyi. 1991. Identification of T-cell stimulatory peptides from the 38-kDa protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 147:1023-1029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization. 2002. Leprosy: global situation. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 77:1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. 2000. Leprosy: global situation. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 75:225-232. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu, H. C., and M. Tokunaga. 1986. Biogenesis of lipoproteins in bacteria. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 125:127-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young, D. B., and T. R. Garbe. 1991. Lipoprotein antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Res. Microbiol. 142:55-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang, M., M. K. Gately, E. Wang, J. Gong, S. F. Wolf, S. Lu, R. L. Modlin, and P. F. Barnes. 1994. Interleukin 12 at the site of disease in tuberculosis. J. Clin. Investig. 93:1733-1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]