Abstract

Natural-resistance-associated macrophage protein 1 (Nramp1) is a divalent cation transporter belonging to a family of transporter proteins highly conserved in eukaryotes and prokaryotes. Mammalian and bacterial transporters may compete for essential metal ions during mycobacterial infections. The mycobacterial Nramp homolog may therefore be involved in Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. Here, we investigated this possibility by inactivating the M. tuberculosis Nramp1 gene (Mramp) by allelic exchange mutagenesis. Disruption of Mramp did not affect the extracellular growth of bacteria under standard conditions. However, the Mramp mutation was associated with growth impairment under conditions of limited iron availability. The Mramp mutant displayed no impairment of growth or survival in macrophages derived from mouse bone marrow or in Nramp1+/+ and Nramp1−/− congenic murine macrophage cell lines. Following intravenous challenge in BALB/c mice, counts of parental and Mramp mutant strains were similar in the lungs and spleens of the animals at all time points studied. These results indicate that Mramp does not contribute to the virulence of M. tuberculosis in mice.

Natural-resistance-associated macrophage protein 1(Nramp1) has been identified as an important component of host antimicrobial activity against intracellular pathogens, including Mycobacterium bovis BCG, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, and Leishmania donovani (23, 47, 43, 5). Nramp1 is expressed by professional phagocytes (48) and is abundant only in tissues containing large numbers of macrophages (spleen, lung, and liver) (8). In resting macrophages, Nramp1 is present in the late endosomal or early lysosomal compartment. Upon phagocytosis of inert particles or live bacteria, Nramp1 is recruited to the membrane of phagosomes, where it remains associated during their maturation into phagolysosomes (24). It has been recognized for many years that inbred mouse strains could be classified as either sensitive or resistant to intracellular pathogens, including mycobacteria. This difference in phenotype was found to be controlled by a specific genetic locus in the proximal region of mouse chromosome 1 (Ith/Lsh/Bcg) and to result from a single inactivating mutation in the gene encoding Nramp1 (51, 22).

The Nramp1 sequence contains the consensus transport motif identified in several prokaryotic and eukaryotic membrane transporters, and the protein is highly homologous to the mammalian protein Nramp2, which functions as a divalent cation transporter (9). Several studies (2, 20, 26, 34, 54) have demonstrated that Nramp1 also transports divalent cations, including Fe2+ and Mn2+, although the direction of divalent cation transport across the phagosome by Nramp1 remains controversial. In phagosomes containing pathogens, the expression of Nramp1 is also associated with enhanced fusion to lysosomes, increased phagosomal acidification (25), and greater bactericidal activity (21). Taken together, these findings suggest that Nramp1 serves as a divalent cation transporter that modifies the composition of the phagosomal compartment. In turn, these changes are thought to promote bacteriostasis by reducing the availability of Fe2+ or other cations essential for the growth of pathogens, impairing the activity of protective bacterial enzymes, facilitating the generation of reactive oxidant species, and/or promoting recruitment of the host vesicular ATPases needed to acidify the phagosome.

The mechanisms through which pathogenic mycobacteria overcome the bactericidal activity of macrophages and develop the ability to multiply in the interior of these cells are not fully defined. Comparative genomics studies have shown that Nramp1 belongs to an ancestral gene family (7), conserved from Saccharomyces cerevisiae to humans. Nramp homologs have been identified in a number of prokaryotes (COG1914) (49). The corresponding proteins, like their mammalian counterparts, function as divalent cation transporters (1, 31, 35). Analysis of the sequence of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase chromosome indicated the presence of a single gene encoding a predicted mammalian Nramp homolog, Mramp, gene number Rv0924c, located in a 5,286-bp region containing five open reading frames oriented in the same direction (12). Mramp is the fourth gene in this series of five and is transcribed as a bicistronic operon (1). The corresponding 428-amino-acid Mramp protein has a hydrophobic core and 10 predicted transmembrane helices and displays 37% sequence identity to the corresponding region of the eukaryotic Nramp1 protein (1). Mycobacterial Mramp sequences from M. tuberculosis H37Rv, M. tuberculosis CDC1551, and Mycobacterium bovis BCG are identical and closely related to those of other bacterial homologs. In particular, the expression of the Nramp homolog from M. tuberculosis (Mramp) in Xenopus laevis oocytes increases the uptake of Fe2+ and Zn2+, and inhibition studies have suggested that Mramp may also interact with Mn2+ and Cu2+ (1). Based on these findings, several authors have proposed that Mramp may be a virulence factor that competes with mammalian metal transporter systems for divalent cations. Thus, additional experimental evidence is needed to evaluate directly the role of Mramp in mycobacterial pathogenicity. To address this question, a strain of M. tuberculosis containing a null mutation in the Mramp gene was generated, and the growth of the wild-type strain and that of the and Mramp mutant strain were compared in iron-depleted culture medium, within monocyte-derived macrophages in vitro, and in an in vivo murine model of tuberculosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

A clinical isolate of M. tuberculosis (designated MT103) was used for these studies. For liquid cultures, mycobacteria were grown in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.), supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80, and 10% Middlebrook ADC (Difco) or Sauton medium (46) with or without addition of 0.025% tyloxcarpol. For solid cultures, 7H11 agar (Difco) containing 10% OADC enrichment was used. Escherichia coli DH5α was cultured in Luria-Bertani broth or agar. When required, kanamycin (final concentrations of 20 or 50 μg/ml, respectively, for MT103 and E. coli; Sigma) and ampicillin (final concentration, 50 μg/ml; Sigma) were added to the growth medium. When necessary, sucrose (2%, wt/vol) was added to the growth medium as a counterselective compound. All cultures were grown at 37°C, except those containing mycobacterial strains transformed with the thermosensitive vector SacB(Ts) (pPR27), which were cultured at 32 or 39°C (41).

Allelic replacement and construction of the Mramp mutant of M. tuberculosis.

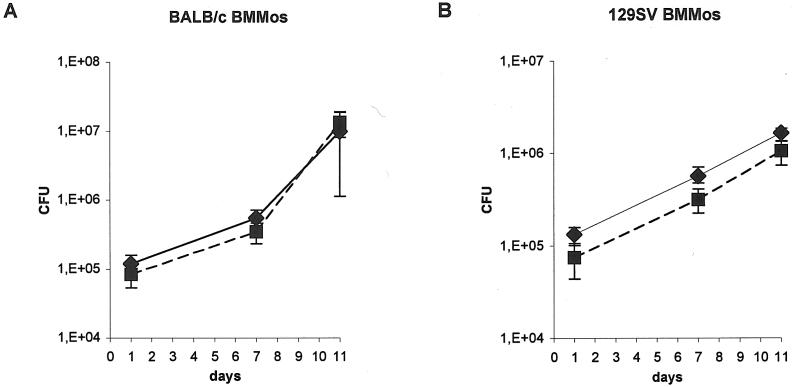

The M. tuberculosis genome sequence database (available from the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ database) was used to design primers Mt9a (5′-GGGTCTAGAGGCTGGCTTAGCAACTCCGAAAG-3′) and Mt9b (5′-GGGTCTAGAACCAACCGCAACACCACATTCAT-3′) for the amplification of a 1,973-bp DNA fragment from M. tuberculosis chromosomal DNA. This fragment contained the gene homologous to mammalian Nramp1 (accession no. Z95210) and its flanking sequences. The resulting PCR product was cloned into the unique XbaI site of pUC19. A deletion-insertion was created by introducing a kanamycin resistance cassette as a single 1,280-bp ApaI fragment between the two ApaI sites (positions 232 and 551) in the Mramp coding sequence (1,284 bp). The insert corresponding to the disrupted Mramp gene construct was excised and subcloned into pXYL4, a pBluescript derivative carrying the xylE colored marker (27). Subsequently, the fragment containing Mramp::aph and xylE was transferred to pPR27 (41), a sacB(Ts) replicative vector, which contains an E. coli origin of replication, a mycobacterial thermosensitive origin of replication, and the sacB gene (used as a counterselective marker). This final construct was used for allelic exchange as previously described (41). Briefly, a mutated allele, Mramp::aph, was inserted into pPR27 along with the xylE reporter gene. M. tuberculosis MT103 was electroporated with the gene replacement sacB(Ts), vector and transformants were selected at 32°C on 7H10-kanamycin. The transformants were then plated on 7H10-kanamycin-sucrose and cultured at 39°C. Clones presenting the phenotype of allelic exchange mutant (Sucr Kmr XylE−) were selected, and their genomic DNA was extracted. Disruption of the Mramp locus was verified by Southern blot analysis using SacI as the restriction enzyme and the Mramp gene as a probe. M. tuberculosis MT103 DNA, which was included as a control, gave a single hybridizing band at 2.8 kb. The allelic exchange mutants, as expected, presented a single hybridizing fragment about 1.0 kb longer than that for the wild-type strain (Fig. 1A). This 1.0-kb difference corresponds to the size of the kanamycin resistance cassette (1,280 bp) minus the 318-bp deletion created between the two ApaI sites within the Mramp gene sequence (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

(A) Southern blot analysis and hybridization profile of the M. tuberculosis Mramp mutant. The first lane corresponds to wild-type MT103 and the second to the M. tuberculosis Mramp mutant strain. Chromosomal DNA was digested with SacI, subjected to electrophoresis, blotted onto membranes, and probed with the Mramp gene probe. (B) Diagram showing the Mramp region in the wild-type (WT) and mutant strains.

Analysis of extracellular mycobacterial growth.

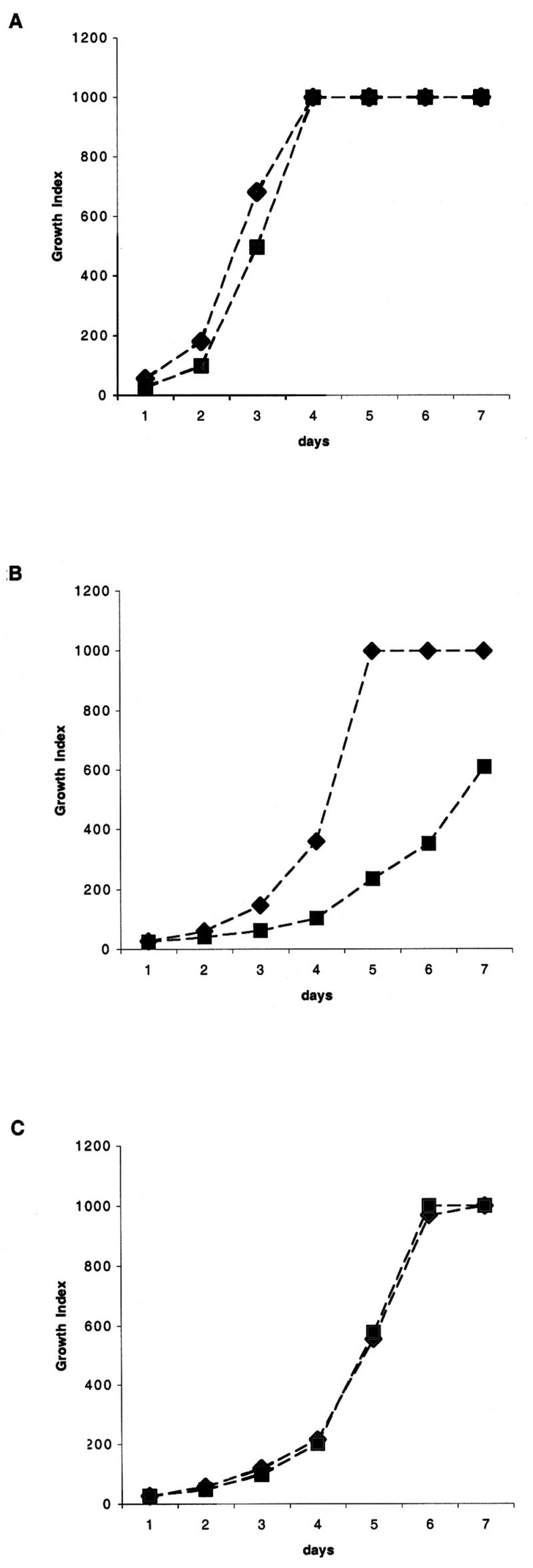

Parental M. tuberculosis or Mramp mutant strains (105 CFU) were inoculated into BACTEC 7H12 broth culture vials and maintained at 37°C. Growth index (GI) readings were obtained daily using the BACTEC 460TB system (Becton Dickinson Diagnostic, Sparks, Md.) to assess mycobacterial growth. In some experiments, 10 to 200 μM 2′2′dipirydyl (DIP) (Sigma) was added to culture vials 24 h prior to inoculation. In some cases, culture medium containing 80 μM DIP was supplemented with 50 μM ferrous sulfate (final concentration) before inoculation with mycobacteria. The graphics presented (Fig. 2) correspond to one of three independent experiments generating similar results.

FIG. 2.

Extracellular growth kinetics of M. tuberculosis wild-type (♦) and Mramp mutant (▪) strains in BACTEC 7H12 medium. Results are shown for growth in standard medium (A); growth in the presence of the iron chelator DIP at a concentration of 80 μM (B), and growth in medium treated with 80 μM DIP and supplemented with 50 μM Fe (C). The growth of strains was monitored by daily determination of GI in the BACTEC 460 system.

Infection of mouse bone marrow macrophages.

Primary 129SV and BALB/c bone marrow-derived macrophages were obtained and cultured as previously described (28). Cells were plated at 2 × 105 cells in 24-well plates and cultured for 7 days, at which time confluent monolayers of macrophages were present. Cultures were then infected with bacterial suspensions of wild-type or Mramp strains at a multiplicity of infection of 0.8. Cultures were incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2. Eighteen hours after infection, the culture medium was removed and the monolayers were washed three times with 500 μl of Hanks' buffered salt solution (Gibco) before adding 800 μl of fresh culture medium. At 1, 7, and 11 days after infection, macrophages were lysed in cell culture lysis reagent (Promega), and the number of intracellular CFU was evaluated by culturing appropriate dilutions of lysate onto plates containing 7H11 or 7H11 kanamycin. The number of CFU was evaluated for each strain in four independent wells at each time point. Data are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD).

Infection of murine macrophage Nramp1+/+ and Nramp1−/− cell lines.

Macrophage lines were derived from the bone marrow of 129SV mice expressing the wild type of the Nramp1 gene and from 129/Nramp1 gene knockout mice carrying a null allele at the Nramp1 locus (51) in the 129/J embryonic stem cells, as previously described (53). Briefly, these cell lines were cultured in antibiotic-free RPMI Glutamax medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum for 48 to 72 h. Then, subconfluent cells were removed and plated at 5 × 104 cells, 900 μl per well, in 24-well plates. After 4 h, cultures were infected with 100 μl of bacterial suspensions of wild-type or Mramp mutant strains at a multiplicity of infection of 0.5. Cultures were incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2. At 1, 4, 7, and 10 days after infection, contents of each well were harvested and pelleted. Cells were resuspended in cell culture lysis reagent (Promega). The number of CFU was evaluated by plating appropriate dilutions of lysate onto plates containing 7H11 or 7H11 kanamycin. As the total contents of each well were used to evaluate mycobacterial growth, controls for mycobacterial extracellular growth were obtained by culturing 2.5 × 104 CFU of wild-type and Mramp mutant strains in the absence of monocytes. Bacteria were counted at each time point in three independent wells for each condition. The data are expressed as means ± SD. As previously reported (29), M. tuberculosis cultured in the absence of monocytes in RPMI 1640 assay medium containing 10% heat-inactivated serum showed little growth (threefold increase in number of CFU at day 10 postinfection [data not shown]).

Mycobacterial growth rate in mice.

BALB/c female mice (8 weeks old) were purchased from Iffa Credo (l'Arbresle, France) and maintained according to Institut Pasteur guidelines for laboratory animal husbandry. Animals were infected intravenously with approximately 105 CFU of parental M. tuberculosis or Mramp mutant strains suspended in 200 μl of 1× phosphate-buffered saline. At various times after infection, five mice from each experimental group were sacrificed. The spleen and lungs of each animal were aseptically removed and homogenized. Bacteria in the organs of infected animals were enumerated by plating 10-fold serial dilutions of organ homogenates onto 7H11 medium (containing kanamycin for the Mramp mutant strain). The data are expressed as the means ± SD of counts obtained for five mice.

RESULTS

Growth of M. tuberculosis Mramp mutant in standard media and under iron-limiting conditions.

Disruption of Mramp did not result in any obvious visual phenotypic differences in colony morphology, nor did it affect bacterial growth in Sauton medium or the enriched media 7H9, 7H11, (data not shown), and 7H12b (Fig. 2A). Thus, the Mramp gene is not essential for growth under standard laboratory conditions.

To assess the role of the Mramp locus in iron uptake, growth rates of the Mramp mutant and parental strains were compared under conditions of iron restriction in vitro, using the BACTEC TB 460 system. This system, used for rapid detection and susceptibility testing of mycobacteria in clinical laboratories, is based on detection of 14CO2 produced by oxidation of [14C]palmitic acid (44, 52). To create an iron-depleted environment, the high-affinity iron chelator DIP (4, 14) was added to the BACTEC 7H12 medium. Iron is required for the growth of mycobacteria in vitro and is an obligate cofactor for at least 40 different enzymes encoded by the M. tuberculosis genome (16). Under conditions of low iron availability, both parental and mutant strains demonstrated impaired growth. Under these conditions, however, the GI and ΔGI of the Mramp mutant were more severely affected than the GI and ΔGI of the wild-type strain (Fig. 2B). In contrast, when growth took place in the presence of 80 μM DIP supplemented with 50 μM Fe, the growth rate of the Mramp mutant strain was similar to that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 2C). Restoration of the growth of the Mramp mutant strain by iron supplementation indicates that iron depletion was responsible for the greater impairment of growth observed for the mutant strain. These results indicate that although Mramp was not required for the growth of M. tuberculosis under iron-deficient conditions, the Mramp gene itself or the Mramp regulon confers a growth advantage on the wild-type strain over the mutant strain in this setting.

Growth of M. tuberculosis Mramp mutant in mouse bone marrow macrophages.

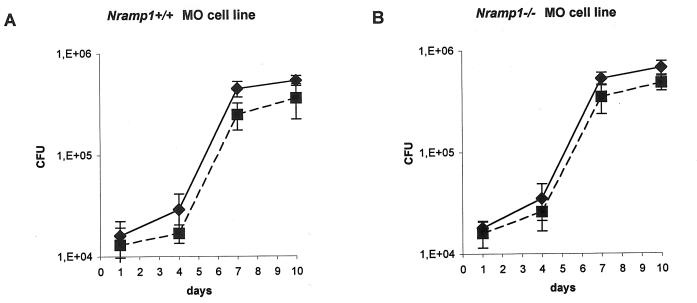

To test the ability of the Mramp null mutant to persist and multiply within professional phagocytes, bone marrow-derived macrophages from mice with an intact Nramp1 gene (129SV mice) and those homozygous for the Asp169 mutation that inactivates Nramp1 (BALB/c) were plated at 2 × 105 cells per well in 24-well plates and infected at a multiplicity of infection of 0.8 with parental and mutant strains. Eleven days after infection, there was no significant difference in the number of viable bacilli counted for the Mramp mutant and the wild-type strain in cells from both murine strains (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Growth of M. tuberculosis wild-type (♦) and Mramp mutant (▪)strains in BALB/c (A) and 129SV (B) mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages. Macrophages (2 × 105) were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 0.8 with parental and mutant strains.

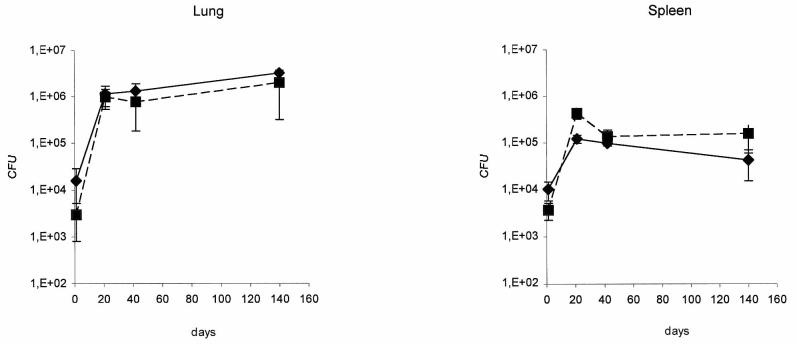

M. tuberculosis Mramp mutant growth in murine macrophage Nramp1+/+ and Nramp1−/− cell lines.

To determine whether the presence of mammalian Nramp1 gene affects the ability of the Mramp mutant strain to persist and multiply within macrophages and also to study a possible interplay between eukaryote and prokaryote Nramp genes, macrophage lines derived from the bone marrow of 129SV mice expressing the wild type of the Nramp1 gene and from 129/Nramp1 gene knockout mice carrying a null allele at the Nramp1 locus (51, 53) were plated at 5 × 104 cells per well in 24-well plates and infected at a multiplicity of infection of 0.5 with parental and mutant strains. At different time points after infection, the cells of individual wells were harvested, pelleted, and lysed and the bacteria were quantified by CFU counting. The growth rates of wild-type and Mramp mutant strains were comparable in both types of macrophage lines tested (Nramp1+/+ or Nramp1−/−) (Fig. 4). Thus, the Mramp mutant displayed no impairment of growth or survival in mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages naturally expressing the wild-type or the mutant allele (nonfunctional) for Nramp1 or in murine Nramp1+/+ or Nramp1−/− macrophage cell lines.

FIG. 4.

Growth of M. tuberculosis wild-type (♦) and Mramp mutant (▪) strains in murine macrophage Nramp1+/+ (A) and Nramp1−/− (B) cell lines. Macrophages (5 × 104) were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 0.5 with parental and mutant strains.

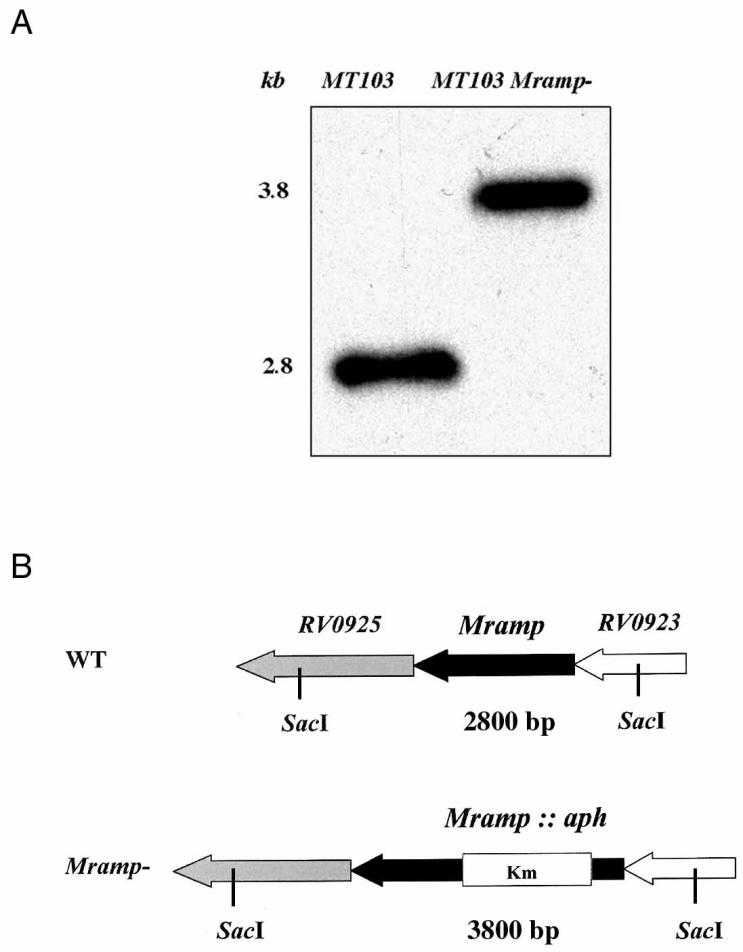

Virulence of M. tuberculosis Mramp mutant in BALB/c mice.

We also compared the growth of the wild type and Mramp mutant in an in vivo model to better evaluate the role of Mramp in mycobacterial virulence. BALB/c mice were infected intravenously with 105 CFU of either the parental M. tuberculosis or the Mramp mutant strain. On days 1, 21, 40, and 140, five infected mice for each strain were sacrificed and viable bacteria present in their spleens and lungs were enumerated. In the present study a late time point (140 days) was included because gene disruption may attenuate mycobacterial persistence and virulence without affecting bacterial growth during the acute phase of infection (38). Mycobacterial number in both lung and spleen were very similar in animals infected with the wild-type and Mramp mutant strains at all time points tested (Fig. 5). These results show that the Mramp mutation in M. tuberculosis does not impair establishment of infection or subsequent mycobacterial growth and persistence in the BALB/c mice.

FIG. 5.

Initial growth and persistence of M. tuberculosis wild-type (♦) and Mramp mutant (▪) strains in mice. BALB/c mice were infected intravenously with 105 viable bacilli of the mutant or wild-type strain. The growth of bacteria in the lungs (left panel) and spleen (right panel) was monitored over time.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have produced a strain of M. tuberculosis containing a null mutation in the gene coding for the Mramp transporter and evaluated the effect of this deletion on mycobacterial growth under a variety of conditions in vitro and in vivo. We found that the growth rates of wild-type and Mramp mutant strains of M. tuberculosis were similar when maintained in several different standard culture media (7H9, Sauton medium, and BACTEC 460TB broth). When cultured in medium to which the high-affinity iron chelator DIP had been added, the growth of both strains was slowed, but the growth of the Mramp mutant strain was impaired to a much greater extent. When DIP-treated medium was supplemented with iron, the growth of both strains was improved, and, importantly, the difference in growth between the wild-type and Mramp mutant strains was eliminated. The addition of iron to DIP-treated medium did not completely restored mycobacterial growth to levels observed in cultures not receiving DIP, indicating that DIP has additional, possibly toxic, effects on mycobacterial growth, independent of its effects on iron availability. Nevertheless, this effect was similar for both the wild-type and Mramp mutant strains. These results are compatible with the hypothesis that the Mramp mutant strain is more susceptible to the iron-limited conditions than the wild-type strain. These findings are consistent with the proposed function of the Mramp gene as a transition metal divalent cation transporter.

In contrast to the reduced extracellular growth observed for the Mramp mutant strain under conditions of iron depletion, no difference in mycobacterial growth was observed in bone marrow-derived murine macrophages between the wild-type and Mramp mutant strains. This was observed using macrophages derived from mice with an intact Nramp1 gene (129SV mice) and those homozygous for the Asp169 mutation that inactivates Nramp1 (BALB/c). Previous studies have shown, however, that loci other than Nramp1 have important bearing on the resistance of mice to M. tuberculosis and that inbred mouse strains lacking functional Nramp1 (e.g., BALB/c) can be more resistant than strains expressing Nramp1 (e.g., 129SV) (33, 39, 40). Thus, it was possible that subtle differences in mycobacterial growth resulting from the presence or absence of Nramp1 expression might have been missed, due to the preponderant effect of other loci on resistance or sensitivity to M. tuberculosis. To further explore this possibility, we also evaluated mycobacterial growth in immortalized macrophage cell lines prepared from 129SV mice and congenic 129SV mice in which both Nramp1 alleles had been inactivated by insertion mutagenesis. Once again, no difference in intracellular growth of wild-type and Mramp mutant mycobacterial strains was observed in these congenic macrophage cell lines. Taken together, these findings suggest that the Mramp mutant is dispensable for the intracellular growth of M. tuberculosis in cultured macrophages, irrespective of the expression of functional Nramp1 by these cells.

Finally, we evaluated the growth of wild-type and Mramp mutant strains in mice following intravenous challenge. For these studies, the BALB/c mouse strain was chosen, because this strain is relatively resistant to M. tuberculosis infection and because this model has proved useful in the investigation of several mycobacterial virulence genes (6, 10, 36, 38, 42). We found, however, that wild-type and Mramp mutant strains established infection similarly in BALB/c mice, with equivalent numbers of bacilli in the lungs and spleen on days 1, 21, 42, and 140. Thus, our results do not support the idea that Mramp is a pathogenicity determinant for infection in mice. In a recent study (31), deletion of the single Nramp gene of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium resulted in only a slight impact on growth of this intracellular pathogen in vivo. In fact, 50% mortality was recorded only 1 to 2 days later in mice infected with the Nramp mutant strain than in mice infected with wild type. The same study showed no effect of bacterial Nramp deletion on cell invasion or survival in cultured HeLa cells or macrophages. Despite these results, it is noteworthy that Mycobacterium leprae, described as an extreme case of reductive genomic evolution, has two copies of a Nramp1 homolog in its genome. As Mycobacterium leprae lacks mycobactin siderophores, one or both of the proteins encoded by these genes may have important physiological roles in iron uptake by this pathogen (11).

Although our results do not demonstrate any impairment in growth of the Mramp mutant strain in vivo or in cultured murine macrophages, further studies will be required to exclude the possibility that Mramp mutant may play a role under some conditions. The susceptibility of mice to M. tuberculosis infection depends on numerous factors, including host genetic background, route of administration, and inoculum size. Thus, the use of a low-dose aerosol infection model, which permits evaluation of the early phases of pulmonary infection, could produce contrasting results. Similarly, infection of more-susceptible mouse strains could produce results different from those presented here. In this regard, the genetic mechanisms controlling infection with virulent M. tuberculosis and the virulent M. bovis Ravanel strain are distinct from those previously shown to play an important role in infection with other intracellular organisms, including the attenuated M. bovis BCG strain and Mycobacterium avium (33). Thus, in mice, the Nramp1 gene does not confer resistance to tuberculosis (40), whereas the recently identified sst1 locus is an important determinant of pulmonary infection with M. tuberculosis, but not M. bovis BCG (33). The extent to which the growth of Mramp mutant strains might be impaired in animals with these different genetic backgrounds remains to be evaluated, although our results using cultured macrophages suggest that Nramp1 expression will not prove to be a major determinant. Finally, we cannot exclude a possible role for Mramp in the pathogenicity of M. tuberculosis under specific experimental or clinical conditions, particularly with respect to iron availability (e.g., malnutrition, severe iron deficiency anemia, chronic disease, or iron overload syndromes) and immunodeficiency.

Studies in vitro (17), in experimental animals (19), and in humans (15) have provided evidence that iron status may affect the occurrence and outcome of mycobacterial infections, and considerable evidence supports the idea that the sequestration of iron (30), and possibly of other metals, may be a commonly employed host response serving to control infectious agents. Human serum is tuberculostatic due to its ability to sequester iron from the bacilli (32), and pulmonary tuberculosis patients are often anemic, suggesting that the host cells operate a strategy aimed at reducing iron availability (3). The phenotype observed for the Mramp mutant in vitro under in iron-limiting conditions shows that Mramp is functional in M. tuberculosis. Given the importance of iron for mycobacterial growth and the iron-limited status of the intravacuolar environment (16), the absence of an effect of inactivation of Mramp on intracellular mycobacterial growth is somewhat surprising but could be accounted for by several mechanisms. A high level of redundancy has been observed in bacterial metal ion uptake and transporter systems (16). Thus, Mramp activity may be compensated by other iron-acquisition strategies. The host cell acquires iron via the transferrin receptor, which internalizes extracellular iron bound to transferrin and lactoferrin. This complex is then trafficked to an early endosomal recycling compartment, where iron is released from the receptor. The mycobacterial phagosome is restricted in its maturation state to that of an early endosome, and it was demonstrated that some plasmalemma-derived constituents, including transferrin, can readily access mycobacterial vacuoles (45). This could allow M. tuberculosis to access the transferrin receptor-transferrin-iron complex (13). Additionally, siderophores of M. tuberculosis are capable of transferring iron from host proteins to specialized mycobactin molecules in the mycobacterial cell wall (18). As discussed by Mazzaccaro et al., another possible mechanism is that M. tuberculosis infection can result in the permeabilization of macrophage phagosomal membranes (37), which could permit access to host cell metal ions within the cytoplasm (50). Alternatively, the ability of M. tuberculosis to inhibit phagosome-lysosome fusion may impair the targeting of proteins involved in the depletion of iron and other divalent cations from the vacuolar environment, thereby limiting the importance of both eukaryotic and prokaryotic Nramp proteins in mycobacterial intracellular growth.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the disruption of the gene homologous to mammalian Nramp1 in M. tuberculosis impairs the ability of this pathogen to growth under conditions of iron depletion, supporting the idea that Mramp serves as an iron transporter. Nevertheless, Mramp was found to be dispensable for mycobacterial growth in standard media, in cultured macrophages, and in macrophage cell lines, irrespective of their Nramp phenotype, and inactivation of Mramp did not impair mycobacterial growth in infected BALB/c mice. These findings suggest that Mramp is not an important determinant of mycobacterial virulence.

Acknowledgments

N.B. was supported by Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa (CNPq), Brazilia, Brazil, grant 200248/98-7.

We thank P. Gros and C. Beaumout for providing 129SV macrophage lines. We are grateful to Cécile Wandersman for helpful discussions and to B. Sonden for critical reading of the manuscript.

Editor: S. H. E. Kaufmann

REFERENCES

- 1.Agranoff, D., I. M. Monahan, J. A. Mangan, P. D. Butche, and S. Krishna. 1999. Mycobacterium tuberculosis expresses a novel pH-dependent divalent cation transporter belonging to the Nramp family. J. Exp. Med. 190:717-724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson, P. G. P., and C. H. Barton. 1999. High level expression of Nramp1G169 in RAW 1264.7 cell transfectants: analysis of intracellular iron transport. Immunology 96:656-662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baynes, R. D., H. Flax, T. W. Bothewell, W. R. Bezwoda, A. P. MacPhail, P. Atinkson, and D. Lewis. 1986. Hematological and iron-related measurements in active pulmonary tuberculosis. Scand. J. Hematol. 36:280-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bearden, S. W., and R. D. Perry. 1999. The Yfe system of Yersinia pestis transports iron and manganese and is required for full virulence of plague. Mol. Microbiol. 32:403-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley, D. J. 1977. Regulation of Leishmania populations within the host. II. Genetic control of acute susceptibility of mice to Leishmania donovani infection. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 30:130-140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camacho, L. R., D. Ensergueix, E. Perez, B. Gicquel, and C. Guilhot. 1999. Identification of a virulence gene cluster of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by signature-tagged transposon mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 34:257-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cellier, M., A. Belouchi, and P. Gros. 1996. Resistance to intracellular infections: Comparative genomic analysis of Nramp. Trends Genet. 12:201-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cellier, M., G. Govoni, S. Vidal, T. Kwan, N. Groulx, J. Liu, F. Sanchez, E. Skamene, E. Schurr, and P. Gros. 1994. Human natural resistance-associated macrophage protein: cDNA cloning, chromosomal mapping, genomic organization, and tissue specific expression. J. Exp. Med. 180:1741-1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cellier, M., G. Prive, A. Belouchi, T. Kwan, V. Rodrigues, W. Chia, and P. Gros. 1995. Nramp defines a family of membrane proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:10089-10093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, P., R. E. Ruiz, Q. Li, R. F. Silver, and W. R. Bishai. 2000. Construction and characterization of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutant lacking the alternate sigma factor gene sigF. Infect. Immun. 68:5575-5580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cole, S. T., K. Eiglmeier, J. Parkhill, K. D. James, N. R. Thomson, P. R. Wheeler, N. Honore, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, K. Mungall, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. M. Davies, K. Devlin, S. Duthoy, T. Feltwell, A. Fraser, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, C. Lacroix, J. Maclean, S. Moule, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, M. A. Quail, M. A. Rajandream, K. M. Rutherford, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, S. Simon, M. Simmonds, J. Skelton, R. Squares, S. Squares, K. Stevens, K. Taylor, S. Whitehead, J. R. Woodward, and B. G. Barrell. 2001. Massive gene decay in the leprosy bacillus. Nature 409:1007-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole, S. T., R. Brosch, J. Parkhill, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, S. V. Gordon, K. Eiglmeier, S. Gas, C. E. Barry III, F. Tekaia, K. Badcock, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. Davies, K. Devlin, T. Feltwell, S. Gentles, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, A. Krogh, J. McLean, S. Moule, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, J. Osborne, M. A. Quail, M.-A. Rajandream, J. Rogers, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, J. Skelton, R. Squares, J. E. Sulston, K. Taylor, S. Whitehead, and B. G. Barrell. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins, H. L., and S. H. E. Kaufmann. 2001. The many faces of host response to tuberculosis. Immunology 103:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawson, M. C., D. C. Elliott, W. H. Elliott, and K. M. Jones. 1993. Stability constants of metal complexes, p. 399-415. In Data for biochemical research, 3rd ed. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 15.De Monye, C., D. S. Karcher, J. R. Boelaert, and V. R. Gordeuk. 1999. Bone marrow macrophage iron grade and survival of HIV-seropositive patients. AIDS 13:375-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Voss, J. J., K. Rutter, B. G. Schroeder, and C. E. Barry III. 1999. Iron acquisition and metabolism by mycobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 181:4443-4451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Voss, J. J., K. Rutter, B. J. Schroeder, H. Su, Y. Zhu, and C. E. Barry III. 2000. The salicylate-derived mycobactin siderophores of Mycobacterium tuberculosis are essential for growth in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:1252-1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gobin, J., and M. A. Horwitz. 1996. Exochelins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis remove iron from human iron-binding proteins and donate iron to mycobactins in the M. tuberculosis cell wall. J. Exp. Med. 183:1527-1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomes, M. S., and R. Apelberg. 1998. Evidence for a link between iron metabolism and Nramp1 gene function in innate resistance to Mycobacterium avium. Immunology 95:165-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goswami, T., A. Bhattacharjee, P. Babal, S. Searle, E. Moore, M. Li, and J. M. Blackwell. 2001. Natural-resistance-associated macrophage protein 1 is an H+/bivalent cation antiporter. Biochem. J. 354:511-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Govoni, G., F. Cannone-Hergaux, C. G. Pfeifer, S. Marcus, S. Mills, D. Hackam, S. Grinstein, D. Malo, B. Finlay, and P. Gros. 1999. Functional expression of Nramp1 in vitro after transfection into murine macrophage line RAW264.7. Infect. Immun. 67:2225-2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Govoni, G., S. Vidal, S. Gauthier, E. Skamene, D. Malo, and P. Gros. 1996. The Ith/Lsh/Bcg locus: genetic transfer of resistance to infections in C57BL/6J mice transgenic for the Nramp1 Gly169 allele. Infect. Immun. 64:2923-2929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gros, P., E. Skamene, and A. Forget. 1981. Genetic control of natural resistance to Mycobacterium bovis (BCG) in mice. J. Immunol. 127:2417-2421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gruenheid, S., E. Pinner, M. Desjardins, and P. Gros. 1997. Natural resistance to intracellular parasites: the Nramp1 protein is recruited to the membrane of the phagosome. J. Exp. Med. 185:717-730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hackam, D. J., O. D. Rostein, W. Zhang, S. Gruenheid, P. Gros, and S. Grinstein. 1998. Host resistance to intracellular infection: mutation of natural resistance-associated macrophage protein 1 (Nramp1) impairs phagosomal acidification. J. Exp. Med. 188:351-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jabado, N., A. Jankowski, S. Dougaparsad, V. Picard, S. Grinstein, and P. Gros. 2000. Natural resistance to intracellular infections: natural resistance-associated macrophage protein 1 (Nramp1) functions as a pH-dependent manganese transporter at the phagosomal membrane. J. Exp. Med. 192:1237-1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson, M., D. C. Crick, and P. J. Brennan. 2000. Phosphatidylinositol is an essential phospholipid of mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 275:30092-30099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson, M., S. W. Phalen, M. Lagranderie, D. Ensergueix, P. Chavarot, G. Marchal, D. N. McMurray, B. Gicquel, and C. Guillot. 1999. Persistence and protective efficacy of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis auxotroph vaccine. Infect. Immun. 67:2867-2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jagannath, C., J. K. Actor, and R. L. Hunter, Jr. 1998. Induction of nitric oxide in human monocytes and monocytes cell lines by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nitric Oxide 2:174-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jurado, R. L. 1997. Iron, infections and anemia of inflammation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 4:888-895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kehres, D. G., M. L. Zaharik, B. B. Finlay, and M. E. Maguire. 2000. The NRAMP proteins of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli are selective manganese transporters involved in the response to reactive oxygen. Mol. Microbiol. 36:1085-1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kochan, I., C. Patton, and K. Ishak. 1963. Tuberculostatic activity of normal sera. J. Immunol. 90:711-719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kramnik, I., W. F. Dietrich, P. Demant, and B. R. Bloom. 2000. Genetic control of resistance to experimental infection with virulent Mycobacterial tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:8560-8565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuhn, E. D., W. P. Lafuse, and B. S. Zwilling. 2001. Iron transport into Mycobacterium avium-containing phagosomes from an Nramp1Gly169-transfected RAW264.7 macrophage cell line. J. Leukoc. Biol. 69:43-49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Makui, H., E. Roig, S. T. Cole, J. D. Helmann, P. Gros, and M. F. Cellier. 2000. Identification of the Escherichia coli K-12 Nramp orthologue (MntH) as a selective divalent metal ion transporter. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1065-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manabe, Y. C., B. J. Saviola, L. Sun, J. R. Murphy, and W. R. Bishai. 1999. Attenuation of virulence in Mycobacterium tuberculosis expressing a constitutively active iron repressor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:12844-12848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mazzaccaro, R. J., M. Gedde, E. R. Jensen, H. M. van Santen, H. L. Ploegh, K. L. Rock, and B. R. Bloom. 1996. Major histocompatibility class I presentation of soluble antigen facilitated by Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 21:11786-11791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKinney, J. D., K. Honer zu Bentrup, E. J. Munoz-Elias, A. Miczak, B. Chen, W. T. Chan, D. Swenson, J. C. Sacchettini, W. R. Jacobs, Jr., and D. P. Russell. 2000. Persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages and mice requires the glyoxylate shunt enzyme isocitrate lyase. Nature 406:735-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Medina, E., and R. J. North. 1998. Resistance ranking of some common inbred mouse strains to Mycobacterium tuberculosis and relationship to major histocompatibility haplotype and Nramp1 genotype. Immunology 93:270-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.North, R. J. North, R. LaCourse, L. Ryan, and P. Gros. 1999. Consequence of Nramp1 deletion to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 67:5811-5814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pelicic, V., M. Jackson, J. M. Reyrat, W. R. Jacobs, Jr., B. Gicquel, and C. Guilhot. 1997. Efficient allelic exchange and transposon mutagenesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:10955-10960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pérez, E., S. Samper, Y. Bordat, C. Guillot, B. Gicquel, and C. Martin. 2001. An essential role for phoP in Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 41:179-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plant, J., and A. A. Glynn. 1976. Genetics of resistance to infection with Salmonella typhimurium in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 133:72-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reddy, M. V., S. Srinivasan, B. Andersen, and P. R. Gangadharam. 1994. Rapid assessment of mycobacterial growth inside macrophages and mice, using the radiometric (BACTEC) method. Tuber. Lung Dis. 75:127-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Russel, D. G., J. Dant, and S. Sturgill-Koszycki. 1996. Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium tuberculosis-containing vacuoles are dynamic, fusion competent vesicles that are accessible to glycosphingolipids from the host cell plasmalemma. J. Immunol. 156:4764-4773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sauton. 1912. Sur la nutrition minerale du bacille tuberculeux. C. R. Acad. Sci. 155:860-861. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Skamene, E., P. Gros, A. Forget, P. A. L. Kongshavin, C. St-Charles, and B. A. Taylor. 1982. Genetic regulation of resistance to intracellular pathogens. Nature 297:506-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stach, J. L., P. Gros, A. Forget, and E. Skamene. 1984. Phenotypic expression of genetically controlled natural resistance to Mycobacterium bovis (BCG). J. Immunol. 132:888-892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tatusov, R. L., D. A. Natale, I. V. Garkavtsev, T. A. Tatusov, U. T. Shankavaram, B. S. Rao, B. Kiryutin, M. Y. Galperin, N. D. Fedorova, and E. V. Koonin. 2001. The COG database: new developments in phylogenetic classification of proteins from complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:22-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teitelbaum, R., M. Cammer, M. L. Maitland, N. E. Freitag, J. Condelis, and B. R. Bloom. 1999. Mycobacterial infection of macrophages results in membrane-permeable phagosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 26:15190-15195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vidal, S., M. L., Tremblay, G. Govoni, S. Gauthier, G. Sebastiani, D. Malo, E. Skamene, M. Olivier, S. Jothy, and P. Gros. 1995. The Ith/Lsh/Bcg locus: natural resistance to infection with intracellular parasites is abrogated by disruption of the Nramp1 gene. J. Exp. Med. 182:655-666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wallis, R. S., M. Palaci, S. Vinhas, A. G. Hise, F. C. Ribeiro, K. Landen, S. H. Cheon, H. Y. Song, M. Phillips, R. Dietze, and J. J. Ellner. 2001. A whole blood bactericidal assay for tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 183:1300-1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wojciechowski, W., J. De Sanctis, E. Skamene, and D. Radizioch. 1999. Attenuation of MHC class II expression in macrophages infected with Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin involves class II transactivator and depends on the Nramp1 gene. J. Immunol. 163:2688-2696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zwilling, B. S., D. E. Kuhn, L. Wikoff, D. Brown, and W. Lafuse. 1999. Role of iron in Nramp1-mediated inhibition of mycobacterial growth. Immunology 95:165-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]