Abstract

Helicobacter pylori infection causes active chronic inflammation with a continuous recruitment of neutrophils to the inflamed gastric mucosa. To evaluate the role of endothelial cells in this process, we have examined adhesion molecule expression and chemokine and cytokine production from human umbilical vein endothelial cells stimulated with well-characterized H. pylori strains as well as purified proteins. Our results indicate that endothelial cells actively contribute to neutrophil recruitment, since stimulation with H. pylori bacteria induced upregulation of the adhesion molecules VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin as well as the chemokines interleukin 8 (IL-8) and growth-related oncogene alpha (GRO-α) and the cytokine IL-6. However, there were large variations in the ability of the different H. pylori strains to stimulate endothelial cells. These interstrain variations were seen irrespective of whether the strains had been isolated from patients with duodenal ulcer disease or asymptomatic carriers and were not solely related to the expression of known virulence factors, such as the cytotoxin-associated gene pathogenicity island, vacuolating toxin A, and Lewis blood group antigens. In addition, one or several unidentified proteins which act via NF-κB activation seem to induce endothelial cell activation. In conclusion, human endothelial cells produce neutrophil-recruiting factors and show increased adhesion molecule expression after stimulation with certain H. pylori strains. These effects probably contribute to the continuous recruitment of neutrophils to H. pylori-infected gastric mucosa and may also contribute to tissue damage and ulcer formation.

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative bacterium common all over the world but having the highest frequencies in developing countries. If not treated, the infection is lifelong and is the most common cause of duodenal ulcer (DU) disease and gastric cancer (6, 7). Approximately 10 to 15% of H. pylori-infected individuals develop severe gastric symptoms, while the majority remain more or less asymptomatic (AS). There are several factors in both the bacterium (26, 49, 56) and the infected host that have been suggested to be of importance for the development of symptoms (15, 25, 44).

H. pylori inflammation is characterized by active chronic gastritis with continuous recruitment and invasion of polymorphonuclear as well as mononuclear cells. The mechanisms behind this unusual inflammation pattern are still unknown, but endothelial cell function and activation are probably key components in this process. The vascular endothelium forms a barrier between blood and matrix but can become permeable to fluids and macromolecules and allow entry of inflammatory cells, immune effector cells, and hematopoietic precursors into the tissue. Endothelial cell activation is a rapid response and includes the secretion of preformed inflammatory mediators from Wiebel-Palade bodies, increased P-selectin expression, and switching to NO metabolic pathways resulting in cytoskeletal or junctional reorganization and in increased vascular permeability (51-54). Increased endothelial cell expression of the adhesion molecules E-selectin (CD62E), VCAM-1 (CD106), and ICAM-1 (CD54) supports the recruitment of leukocytes to the site of inflammation and enhances ongoing inflammatory processes (2, 37). Leukocyte recruitment is further increased by the production and secretion of a broad array of chemokines and cytokines by endothelial cells as well as the surrounding inflamed tissue.

Chemokines are small chemotactic proteins with four conserved cysteines forming two essential disulfide bonds. Depending on the position of the two N-terminal cysteine residues, chemokines are divided into different classes. Generally, CXC chemokines such as IL-8 and growth-related oncogene alpha (GRO-α) preferentially recruit neutrophils, whereas CC chemokines such as RANTES and gamma interferon-inducible protein 10 (IP-10) mainly attract lymphocytes and monocytes (5).

Previous studies showed that the endothelium contributes to the inflammatory response with regard to cytokine and chemokine production as well as leukocyte recruitment after infection with pathogenic bacteria and viruses (22, 24, 36, 47). During inflammatory responses, the transcription factor nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) plays a key role in the regulation of participating genes (4, 38). In endothelial cells, NF-κB regulates the expression of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin (13, 14) and is considered an early activation signal. The expression of many cytokine and chemokine genes (i.e., those for IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α]) is also under NF-κB control (35). NF-κB activation has been shown during infection with H. pylori, Shigella flexneri, Staphylococcus aureus, and Chlamydia pneumoniae (11, 21, 29, 40, 45).

It is still unknown, however, to what extent endothelial cells play a role in H. pylori-associated gastritis. Therefore, we established a model system for investigating bacterial factors important for neutrophil recruitment by using human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) stimulated with several different, well-characterized H. pylori strains isolated from DU patients as well as AS carriers. These strains expressed different combinations of virulence factors, such as the cytotoxin-associated gene pathogenicity island (CagPAI), vacuolating toxin A (VacA), blood group binding adhesin A (BabA), and Lewis blood group antigens. In addition, we stimulated HUVEC with purified H. pylori proteins or H. pylori culture filtrates to determine if H. pylori stimulation of endothelial cells contributes to the continuous recruitment of neutrophils seen during H. pylori-induced inflammation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and characterization of H. pylori strains.

H. pylori strains were isolated from the duodenum of four adult Swedish patients suffering from active or recent DU disease (strains Hel 301, 305, 325, and 333; Table 1) or from the stomach of four adult Swedish AS subjects (strains Hel 73, 312, 314, and 340; Table 1) as previously described (26). Strains were stored in a freeze-drying medium containing 20% glycerol at −80°C. A reference strain, CCUG 17874, was also included in the study (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characterization of the H. pylori strains used

| Strain | Expression ofa:

|

Origin | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CagPAI | VacAb | Lewis blood group antigens | BabA | ||

| Hel 73 | + | s1/m1 | x | ND | AS |

| Hel 305 | + | s1/m1 | x | + | DU |

| Hel 312 | + | s1/m1 | x | − | AS |

| Hel 301 | + | s2/m? | + | DU | |

| Hel 325 | + | s1/m2 | − | DU | |

| Hel 314 | IM | s1/m2 | − | AS | |

| Hel 333 | − | s2/m2 | a, b | ND | DU |

| Hel 340 | + | s1/m2 | x, y | + | AS |

| CCUG 17874 | + | s1/m1 | ND | Reference strain | |

+, positive; −, negative; IM, intermediate (deletion of genes 6, 13 to 19, and 21 to 28 of CagPAI); ND, not done; AS, AS individuals; DU, DU patients.

s, signal sequence; m, middle region; ?, unable to detect the m region in this strain.

The different vacA genotypes were identified by PCR with primers VA1F and VA1XR for typing of the signal sequence and primers VAG-F and VAG-R for the middle-region variants as described by van Doorn et al. and Atherton et al. (3, 50). The expression of other putative virulence factors by the strains, i.e., H. pylori neutrophil-activating protein (HP-NAP), H. pylori adhesin A (HpaA), urease, and Lewis blood group antigens (Lex, Ley, Lea, Leb, and sialyl-Lex), was determined by a whole-cell direct enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (46, 49). H. pylori BabA was detected by using an Leb oligosaccharide probe hybridization assay (12).

DNA microarray chips were generated to contain PCR products from all open reading frames (HP0520 to HP0547) in the cag pathogenicity island, based upon the DNA sequence of strain 26695 (A. Sillén et al., unpublished data). Fluorescence-labeled genomic DNA from each strain was prepared by random priming. Hybridization was performed overnight, and the arrays were dried by centrifugation before being scanned with a GMS 418 array scanner (Genetic MicroSystems Inc., Woburn, Mass.).

All strains were tested on at least two occasions for each antigen or gene.

Culturing of H. pylori bacteria.

For stimulation of HUVEC, H. pylori bacteria were cultured on Columbia-iso agar plates at 37°C in a microaerophilic milieu. After 4 days, the bacteria were scraped off the plates and resuspended in 3 to 5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The optical density (OD) of the suspension was determined at 600 nm (Shimadzu UV-1201 apparatus; Lambda Polynom, Stockholm, Sweden) and adjusted to a final absorbance of 1.0 (OD, 1.0) in PBS, corresponding to 5 × 109 H. pylori bacteria/ml and 5 × 108 CFU/ml. The suspension was used directly or kept on ice for a maximum of 1 h to avoid damage to the bacteria. This type of bacterial suspension was used throughout the study and was produced in the same way at all times.

Production of H. pylori filtrates.

To investigate whether H. pylori secretes factors responsible for the activation of endothelial cells into the environment, we cultured bacteria in endothelial cell culture medium under the same conditions as those used for the stimulation of endothelial cells with bacteria (see below). H. pylori strains Hel 312 and 333 were grown and resuspended as described above, and 2.5 ml was added to 48 ml of medium in a petri dish and incubated for 6 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. The medium was collected and subjected to sterile filtration, and 25 ml was heat inactivated for 35 min at 85°C. These suspensions are hereafter designated filtrates. After being cooled to room temperature, both the inactivated and the untreated filtrates were stored at −70°C until use. Two-milliliter samples of these filtrates were used in the experiments, since bacterial stimulation was performed with 2 ml of cell culture medium.

Purification of H. pylori proteins.

Urease and heat shock protein 60 (Hsp60) were kindly provided by Ingrid Bölin and were purified from H. pylori strain E32 by combining the methods of Dunn et al. and Evans et al. (20, 23). Membrane proteins (MP) were prepared from H. pylori strain 305 by sonication followed by differential centrifugation as previously described (9). AstraZeneca Research Center in Boston, Mass., kindly provided recombinantly produced H. pylori HpaA. HP-NAP was kindly provided by S. Nyström, AstraZeneca, Umeå, Sweden (49). Thoroughly described methods for protein purification can be found in Thoreson et al. (reference 49 and references therein).

Possible lipopolysaccharide contamination in the protein preparations was removed by incubating 200 μg of each protein/ml with 20 μg of polymyxin B (Sigma)/ml for 1 h in M200 medium (Cascade Biologics Inc., Portland, Oreg.) at room temperature. Polymyxin itself did not affect the expression of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, or E-selectin or chemokine production compared to the results for the negative control (data not shown).

Subculturing of endothelial cells.

Approximately 500,000 HUVEC, passage 1, were purchased from Cascade Biologics Inc. Upon arrival, the cells were plated in a 75-cm2 plastic bottle (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) and grown to confluence by using M200 medium supplemented with low-serum growth supplement (Cascade Biologics Inc.), with a medium change every 48 h. When the culture had reached confluence, the cells were trypsinized by using 0.25 mg of trypsin-EDTA (Cascade Biologics Inc.)/ml, and each bottle was split 1:3. This procedure was repeated until the cells had reached passage 4, after which the cells were frozen in fetal calf serum containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma) at a concentration of 106 cells/ml. The cells were then stored in liquid nitrogen. For further culturing, HUVEC were diluted to a final concentration of 4.2 × 104 cells/ml in M200 medium containing low-serum growth supplement. Two milliliters of the suspension was added to each well of a 12-well plate (Corning Costar, Badhoevedorp, The Netherlands) and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. The cultures reached confluence within 2 to 3 days and were used after a maximum of 3 days. The medium was always changed before the cells were used in experiments. All medium contents contained less than 0.03 U of endotoxin/ml, as determined by the Limulus test. HUVEC at passages 4 to 7 were used throughout the experiments (34).

Stimulation of HUVEC with H. pylori bacteria, purified proteins, or culture filtrates.

To examine adhesion molecule expression by HUVEC, 100 μl of H. pylori suspensions, 10 μg of purified proteins/ml, or 2 ml of H. pylori filtrates was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for 6.5 h at 37°C in air with 5% CO2. The incubation time had been determined in a previous pilot experiment to be optimal for the expression of the adhesion molecules under study (data not shown). To study chemokine and cytokine production by H. pylori-stimulated HUVEC, 10 μl of each bacterial suspension, 2 ml of H. pylori filtrates, or 10 μg of purified proteins/ml was added to HUVEC cultures in a final volume of 2 ml. Pilot kinetic experiments had shown that 24 h of incubation induced maximal chemokine and cytokine production (data not shown). After stimulation, the supernatants, in duplicate, were pooled and stored at −70°C until analysis. Each experiment was performed a minimum of three times on different occasions.

FACS analyses of adhesion molecule expression.

After stimulation, the culture medium was removed, and the cell layers were gently detached by use of 0.25 mg of trypsin-EDTA/ml. The cells were washed twice in PBS containing 1.46 g of EDTA/liter, 2.5 g of bovine serum albumin/liter, 0.2 g of NaN3/liter, and 2% AB-positive human serum (fluorescence-activated cell sorting [FACS] washing buffer [FWB]), resuspended in 1 ml of FWB, and placed on ice.

Cell suspensions were divided into five aliquots and stained with mouse monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) (5 μg/ml) against VCAM-1, ICAM-1, E-selectin, or CD31 (all from Dakopatts AB, Älvsjö, Sweden) diluted in FWB. A mouse immunoglobulin G1 MAb specific for Aspergillus niger glucose oxidase was used as a negative control (Dakopatts AB). After 30 min of incubation on ice, the cells were washed once in FWB, and F(ab′)2 fragments from a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse MAb (Dakopatts AB) were added at a concentration of 10 μg/ml. After a final 30 min of incubation, the cells were washed, fixed with Cellfix (Becton Dickinson, Erembodegem, Belgium), and then analyzed for adhesion molecule expression by flow cytometry (Facs-Calibur; Becton Dickinson).

Immunofluorescence analysis of adhesion molecule expression.

HUVEC were grown to confluence on chamber slides (Falcon; Becton Dickinson Labware Europe, Le Pont de Claix, France) and stimulated as described above for 6 h with H. pylori strain Hel 312 or 333 or TNF-α. The cells were washed and then fixed in 100% ice-cold acetone for 10 min. After being air dried, the cells were stained with the same MAbs (5 μg/ml) as those used in the FACS analyses overnight at 4°C. After being washed, the sections were incubated with FITC-conjugated F(ab′)2 fragments of a rabbit anti-mouse MAb (10 μg/ml) for 3 h, and propidium iodide (Sigma) was added for contrast nuclear staining. The slides were mounted by using Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.), and staining was evaluated by using a Leica microscope at a magnification of ×200.

Detection of secreted cytokines and chemokines.

The levels of IL-6, IL-8, GRO-α, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IP-10, and RANTES in the cell supernatants were determined by ELISAs as previously described (28). The detection limits were 3.9 pg/ml for IL-8 and IL-6 and 31 pg/ml for GM-CSF, RANTES, GRO-α, and IP-10.

Detection of IL-8 mRNA.

HUVEC stimulated with H. pylori bacteria for 0.5 and 3 h were washed and detached as described above, resuspended in 25 μl of PBS, and stored at −70°C until mRNA was prepared by using a S.N.A.P. total RNA isolation kit (Invitrogen, Leek, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The amount and purity of mRNA were analyzed by spectrophotometry at 260 nm and by calculating the A260/A280 ratio, respectively. The purified RNA fractions were stored at −70°C until used for reverse transcription (RT)-PCR.

In each RT-PCR, specific primers for IL-8 (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) were used at a concentration of 0.4 μM in a final volume of 25 μl containing 100 ng of mRNA, reaction buffer, and Superscript II RT-Taq mix (Gibco BRL, Liding, Sweden) to detect IL-8 mRNA. Primers for the β-actin housekeeping gene were included in each tube to allow semiquantitative analysis. The reaction was performed by using a Gene Amp PCR System 2000 machine (Wallac Sverige AB, Upplands Väsby, Sweden) and analyzed on a 2% agarose gel stained with EtBr. The intensity of the bands was determined by using the ImageQuant program (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.), and relative IL-8 mRNA expression was calculated as the intensity of IL-8 bands divided by the intensity of β-actin bands.

Detection of NF-κB activation in H. pylori-stimulated HUVEC.

HUVEC were cultured in T-75 flasks (Nunc) to confluence. After a medium change, the cells were allowed to stand for 1 h, and then 1.25 ml of H. pylori suspension was added. After 6 h of incubation, the HUVEC monolayers were washed in PBS. Then, the cells were lysed by using a lysing buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 10% Nonidet P-40 in PBS; a Complete Mini Protease Inhibitor Cocktail tablet (Roche Diagnostics) was added just prior to use. After 15 min of incubation on ice, any nonlysed cells were scraped off and centrifuged together with the cell lysate. The pellet was stored at −70°C until analysis by an electromobility shift assay (EMSA) performed as previously described (42). Briefly, binding buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.8], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol), 1 μg of poly(dI-dC), and 0.5 ng of 32P-labeled DNA probe corresponding to the κB site of the H-2KB promoter were added to 5 μg of nuclear extracts and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The samples were run on a 5% polyacrylamide gel, and the gel was dried, exposed to a PhosphorImager screen (Molecular Dynamics), and analyzed by using ImageQuant software.

Adhesion of H. pylori to HUVEC.

Nine hundred microliters of H. pylori culture (OD, 1.0) was mixed with 100 μl of FITC (Sigma) to a final concentration of 0.1 μg/ml of FITC. After 30 min of incubation on ice, the FITC-labeled bacteria were centrifuged, resuspended in 100 μl of PBS, placed on top of 1,400 μl of AB-positive serum, and centrifuged. This procedure was repeated until the supernatants were free of unbound FITC. The bacteria were then resuspended in 500 μl of PBS and placed on ice. Culturing of the labeled bacteria confirmed that the staining procedure did not influence viability, and there was no difference in the labeling efficiencies between the various strains. Two hundred microliters of FITC-labeled H. pylori was added to 250,000 newly trypsinized HUVEC, and the mixture was incubated on ice for 30 min and washed. Bacterial binding to HUVEC was analyzed by flow cytometry by detecting the fluorescence intensity of HUVEC as a measurement of H. pylori binding. As negative controls, both unstained H. pylori bound to HUVEC and untreated HUVEC were used.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical evaluations were performed by using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple-comparison tests.

RESULTS

Adhesion molecule expression after stimulation of HUVEC with H. pylori bacteria.

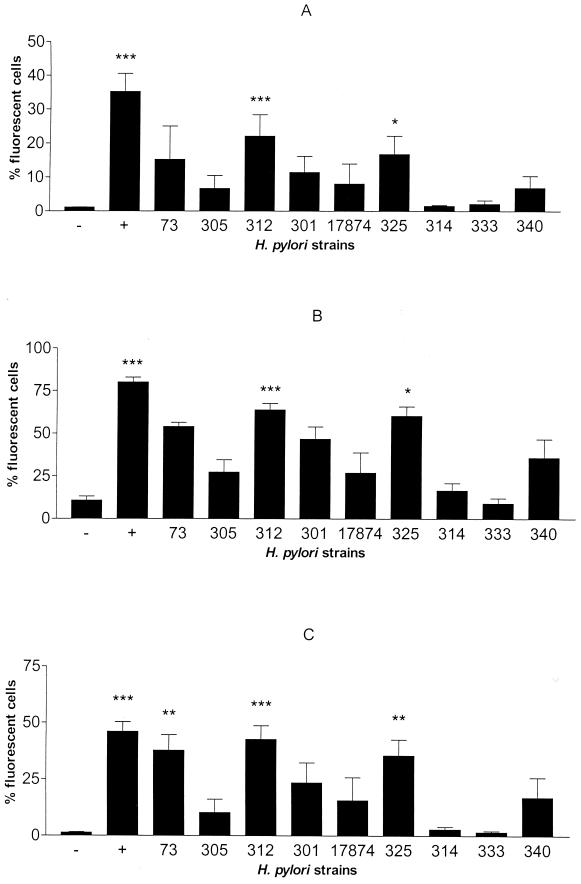

HUVEC stimulated for 6.5 h with nine selected strains of H. pylori bacteria with different characteristics (Table 1) were analyzed for the expression of the adhesion molecules VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin. There was a large but consistent variation between the strains in the levels of adhesion molecule expression induced (Fig. 1). Of the nine strains tested, Hel 312 and 325 induced significantly increased expression of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin compared to the results for the unstimulated control (Fig. 1). H. pylori strains CCUG 17874 and Hel 301, 73, 305, and 340 induced somewhat increased expression of these adhesion molecules compared to the results for the negative control, but only Hel 73 induction of E-selectin reached statistical significance (Fig. 1C). In contrast, H. pylori strains Hel 314 and 333 did not induce any increased expression of the adhesion molecules studied. TNF-α (100 ng/ml), which resulted in a significant increase, was used as a positive control for all adhesion molecules examined (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Graphic representation of adhesion molecule expression by HUVEC after stimulation with H. pylori bacteria. VCAM-1 (A), ICAM-1 (B), and E-selectin (C) expression by HUVEC was determined by using flow cytometry after 6.5 h of stimulation with a 100-μl suspension (OD, 1.0) of H. pylori strain Hel 73, 305, 312, 301, 325, 314, 333, or 340 or CCUG 17874. −, medium alone; +, positive control, TNF-α (100 ng/ml). Bars represent the geometric mean and standard error of the mean. Statistical evaluation of control and stimulated samples was performed by one-way analysis of variance (Kruskal-Wallis test) followed by Dunn's multiple-comparison tests. P values were <0.001 (three asterisks), <0.01 (two asterisks), and <0.05 (one asterisk) (n ≥ 4).

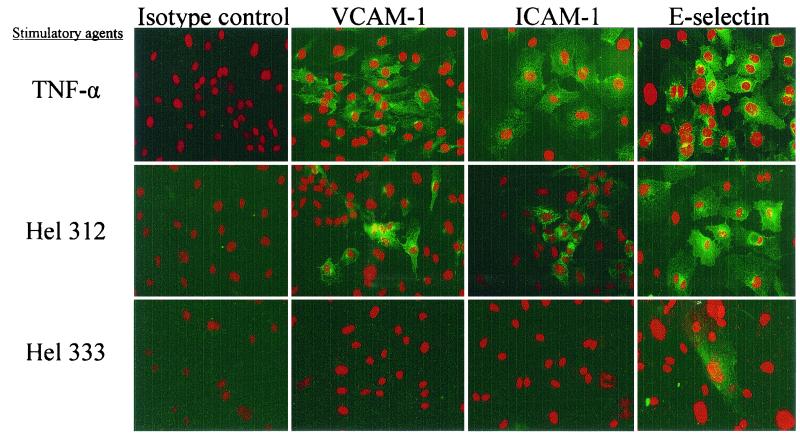

In order to determine the cellular distribution of adhesion molecules, HUVEC were cultured on slides, stimulated with H. pylori strain Hel 312 or 333, and subsequently stained with fluorescent antibodies directed against the adhesion molecules VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin. Unstimulated HUVEC did not express detectable levels of any of the studied markers. However, in agreement with the results obtained from the flow cytometry analysis, stimulation with TNF-α as well as with strain Hel 312 resulted in markedly increased expression of the adhesion molecules ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and E-selectin compared to the results for the negative control (Fig. 2). The intensity of the staining was highest around the nucleus and was mainly found in granule-like arrangements. Furthermore, the stained cells were not equally distributed all over the visual field. Stimulation with strain Hel 333 induced only a slight upregulation of E-selectin compared to the results for the unstimulated control (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Adhesion molecule expression by HUVEC after stimulation with H. pylori bacteria. VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin expression by HUVEC cultured on slides was determined after 6.5 h of stimulation with a 100-μl suspension (OD, 1.0) of H. pylori strain Hel 312 or 333 or with 100 ng of TNF-α/ml. Sections were stained with an MAb against each adhesion molecule and developed with FITC-conjugated F(ab′)2 fragments of a rat anti-mouse MAb (green). Propidium iodide was used for contrast nuclear staining (red). Each field is representative of the whole slide, and the figure shows one representative experiment out of two. Magnification, ×138.

Cytokine and chemokine production after stimulation of HUVEC with H. pylori bacteria.

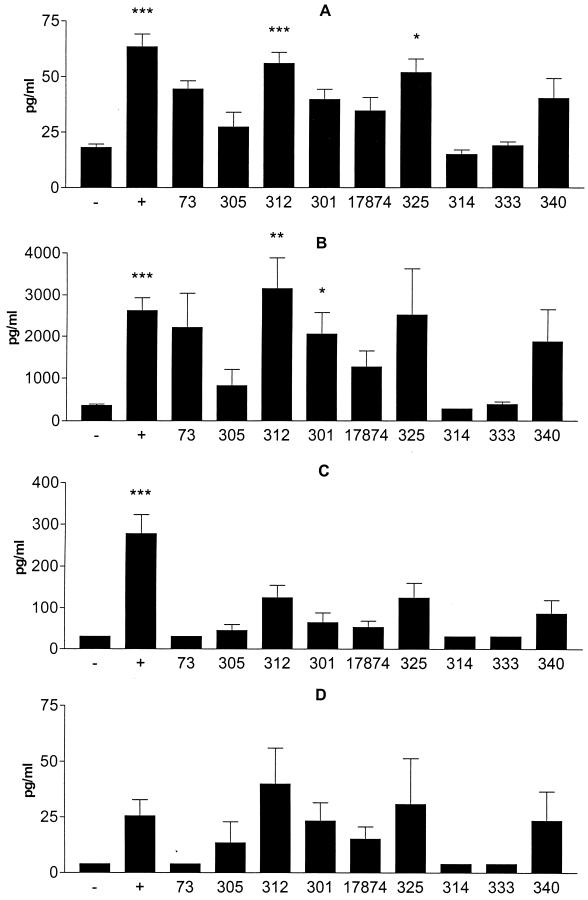

We also analyzed supernatants from HUVEC stimulated with H. pylori bacteria for the production of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and GM-CSF as well as the chemokines IL-8, GRO-α, RANTES, and IP-10. In agreement with the upregulation of adhesion molecules, strains Hel 312 and 325 as well as TNF-α induced significantly increased IL-6 production. In contrast, H. pylori strains Hel 314 and 333 did not induce any increased IL-6 production (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, strains Hel 301 and 312 significantly stimulated IL-8 secretion, whereas strains Hel 314 and 333 did not induce any IL-8 production (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Chemokine and cytokine production by HUVEC after stimulation with H. pylori bacteria. IL-6 (A), IL-8 (B), GRO-α (C), and GM-CSF (D) levels were determined by using an ELISA and culture medium from HUVEC stimulated for 24 h with a 10-μl suspension (OD, 1.0) of H. pylori strain Hel 73, 305, 312, 301, 325, 314, 333, or 340 or CCUG 17874. −, medium alone; +, positive control, TNF-α (100 μg/ml). Bars represent the geometric mean and standard error of the mean. Statistical evaluation of control and stimulated samples was performed by a one-way analysis of variance (Kruskal-Wallis test) followed by Dunn's multiple-comparison tests. P values were <0.001 (three asterisks), <0.01 (two asterisks), and <0.05 (one asterisk) (n ≥ 4).

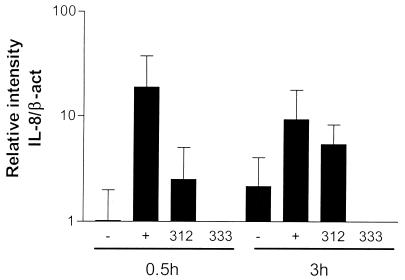

IL-8 mRNA expression was evaluated by RT-PCR. After stimulation of HUVEC with TNF-α for 0.5 h, slight, if any, induction of IL-8 mRNA was observed compared to the results for unstimulated cells. After 3 h of stimulation, this expression was further increased (Fig. 4). Stimulation of HUVEC with strain Hel 312 did not induce IL-8 mRNA expression until 3 h after stimulation (Fig. 4). The IL-8 mRNA level in H. pylori-stimulated cells was even higher than that induced by the positive control, TNF-α. In agreement with the results of the protein analyses, stimulation with strain Hel 333 did not result in an increase in the IL-8 mRNA level at any of the time points studied. These results indicate that H. pylori-induced IL-8 secretion resulted from de novo protein synthesis and not release from the Wiebel-Palade bodies of the endothelial cells.

FIG. 4.

IL-8 mRNA expression in HUVEC after H. pylori stimulation. HUVEC were stimulated with H. pylori Hel 312 or 333 for 0.5 or 3 h, and IL-8 mRNA expression was measured by using RT-PCR. −, medium alone; +, positive control, TNF-α (100 ng/ml). Bars represent the geometric mean and standard error of the mean. Relative IL-8 mRNA expression was calculated as the intensity of IL-8 bands divided by the intensity of corresponding β-actin (β-act) bands (n = 3).

We also analyzed the production of several other chemokines from HUVEC stimulated with H. pylori bacteria. Strains Hel 301, 312, 325, and 340 induced somewhat increased production of GRO-α (Fig. 3C) and GM-CSF (Fig. 3D), but none of the responses was significantly different from that of the negative control. None of the H. pylori strains tested induced any detectable production of RANTES or IP-10. However, the capacity of HUVEC to secrete these chemokines was demonstrated by stimulation with TNF-α (data not shown). In addition, the effect of H. pylori bacteria on endothelial cells was not mediated by autocrine TNF-α stimulation, since blocking of TNF-α did not affect the stimulatory effect (data not shown).

These results show that certain, but not all, clinical isolates of H. pylori have the ability to activate endothelial cells. This ability was not associated with the clinical presentation of the infected individuals and was not entirely dependent on the expression of the known virulence factors CagPAI, VacA, Lewis blood group antigens, and BabA.

Adhesion of H. pylori bacteria to HUVEC.

Since we observed differences in the abilities of H. pylori strains to activate HUVEC, we wanted to determine whether the strains used had different adhesion capacities that could explain these differences. Various FITC-labeled H. pylori strains were incubated with HUVEC and analyzed by FACS. All strains used in this study bound to HUVEC, although with various efficiencies. However, no correlation between binding efficiency and the capacity to activate HUVEC was found (data not shown). Therefore, factors other than bacterial adhesion are probably involved in the activation of endothelial cells.

NF-κB activation in H. pylori-stimulated HUVEC.

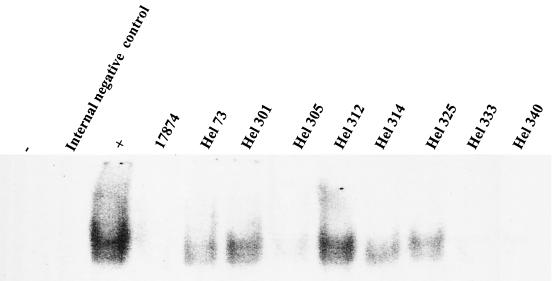

To examine whether the differences between the bacterial strains were mediated by the NF-κB pathway, we analyzed NF-κB activation in HUVEC stimulated with various H. pylori strains by using an EMSA. H. pylori strains Hel 73, 301, and 312 as well as the positive control, TNF-α, all induced the activation of NF-κB (Fig. 5). Strains Hel 314 and 325 induced modest activation of the NF-κB system, whereas H. pylori strains 17874 and Hel 305, 333, and 340 did not induce any detectable activation compared to the results for the unstimulated control (Fig. 5). These results suggest that the abilities of certain H. pylori strains to induce transcriptional activation and induction of de novo synthesis of chemokines and adhesion molecules are mediated by NF-κB activation.

FIG. 5.

NF-κB activation in HUVEC after H. pylori stimulation. HUVEC were stimulated with H. pylori bacteria for 6 h, and NF-κB activation was assessed by an EMSA. −, unstimulated cells; +, positive control, TNF-α (100 ng/ml). The figure shows one representative experiment out of three.

Stimulation of HUVEC with H. pylori filtrates.

When HUVEC were stimulated with H. pylori filtrates, moderately increased expression of E-selectin could be detected with the strain Hel 312 filtrate but not with the strain Hel 333 filtrate. Heat inactivation of the Hel 312 filtrate inhibited the stimulatory effect. Neither VCAM-1 nor ICAM-1 was upregulated after stimulation with any of the filtrates. These results indicate that heat-labile secreted H. pylori proteins contribute to the stimulation of endothelial cells.

Stimulation of HUVEC with purified H. pylori proteins.

Since secreted products from H. pylori bacteria could upregulate E-selectin expression and chemokine production, we wanted to evaluate whether some putative H. pylori virulence factors were involved in this process. We therefore stimulated HUVEC with purified urease, HpaA, Hsp60, HP-NAP, and MP. A slight increase in ICAM-1 expression was seen after stimulation with 10 μg of HP-NAP, HpaA, and MP/ml, whereas urease and Hsp60 did not induce any ICAM-1 expression. In addition, HP-NAP and HpaA induced slight upregulation of E-selectin expression compared to the results for the negative control. VCAM-1 expression was not increased after stimulation with any of the purified H. pylori proteins.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that H. pylori stimulates endothelial cells to upregulate adhesion molecule expression and to increase the production of neutrophil-recruiting chemokines. There were, however, large variations between the strains, and no single known virulence factor could be identified as being responsible for the variations seen in this study. Neither was it of any importance whether the strains were isolated from DU patients or AS individuals.

Vascular endothelial cells are important in the inflammatory cascade, because they respond rapidly to different stimuli by producing leukocyte-recruiting agents in the form of cytokines and chemokines. Previous studies showed that infection with S. aureus, Rickettsia conorii, or Borrelia burgdorferi induces an increase in chemokine (IL-8 and monocyte chemotactic protein 1) and cytokine (IL-6) production from the endothelium (10, 31, 47, 48). Endothelial cells also direct migrating cells into the tissue via the upregulation of adhesion molecules, such as VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin. Thus, autoimmune reactions and B. burgdorferi, C. pneumoniae, and cytomegalovirus infections all increase the expression of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin in endothelial cells (8, 19, 32).

A previous study by Hatz et al. (27) showed that individuals suffering from H. pylori-associated antral gastritis have increased expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 on endothelial cells, but they did not find any E-selectin expression. However, when we analyzed the expression of adhesion molecules on endothelial cells after stimulation with H. pylori, we could detect significantly increased expression of all these adhesion molecules. Interestingly, there was a large but very consistent variation among the H. pylori strains used in the ability to induce adhesion molecule expression. The same strains that were potent inducers of adhesion molecules also induced increased production of IL-8, GRO-α, IL-6, and GM-CSF. The clinical isolates selected for this study were collected from both AS individuals and DU patients. They also expressed different combinations of several known virulence factors. The H. pylori strains inducing the highest response (strains Hel 312 and 325) differed in their expression of the Lewis blood group antigens and VacA. In addition, they originated from an AS carrier and an individual with DU disease, respectively. However, they were both CagPAI positive. In contrast, another CagPAI-positive strain (Hel 305) was among the least potent of the strains. The strain lacking CagPAI (Hel 333) was also a poor inducer of adhesion molecules and chemokines. Unfortunately, we did not have the ability to make isogenic mutants of the most potent strains (Hel 312 and 325); therefore, we cannot exclude the effect of CagPAI-encoded factors. Crabtree et al. (16-18) showed that IL-8 production in H. pylori-infected individuals is correlated with CagPAI-positive strains. The importance of CagPAI in the induction of other chemokines and cytokines (e.g., IL-6, GRO-α, and GM-CSF) has, however, not been studied before. Taken together, our results suggest that mediators encoded by CagPAI may play a role in strain potency but are not the only bacterial products involved in endothelial cell activation.

Several virulence factors other than CagPAI may also play an important role in the outcome of H. pylori infection. Previous studies by our group showed that, in addition to having higher densities, strains expressing CagA, Ley, and BabA are more often found in DU patients than in AS carriers (26, 49). Zheng et al. showed a correlation between ulcer formation and strains expressing Lewis antigens but not the CagA, VacA, or IceA phenotype in an Asian population (56). In contrast, other studies did not find any correlation between Lewis antigen or CagPAI expression and the severity of disease (39, 43). Finally, when strains from four different countries were compared, no correlation between IceA, CagA, or VacA and the outcome of disease could be found (55). In our study, the expression of VacA, Lewis antigens, or BabA by the H. pylori strains did not influence endothelial cell activation; therefore, we suggest that some other, possibly as-yet-uncharacterized, factor is involved in endothelial cell activation together with CagPAI.

To try to determine in greater detail the nature of the stimulatory factor(s), several experiments were performed. First, we examined whether the binding of H. pylori to endothelial cells contributed to endothelial cell activation by quantifying the adhesion of FITC-labeled H. pylori to HUVEC. All H. pylori strains bound to the endothelium, and there were differences in binding efficiency between the strains. However, the binding efficiency of the H. pylori strains in vitro did not seem to influence the activation of endothelial cells, indicating that other factors are responsible for endothelial cell activation. We believe that H. pylori bacteria bind to HUVEC with other molecules besides BabA, since HUVEC probably lack the expression of Lewis as well as ABO blood group antigens (41).

NF-κB is an important regulatory factor during inflammation and mediates the induction of IL-8 and GRO-α and the upregulation of adhesion molecules by endothelial cells (35, 38). Previous studies showed that NF-κB is activated during H. pylori infection in different cell types (1, 33) and that CagPAI-positive strains are more potent activators of NF-κB than strains lacking CagPAI (45). Furthermore, Isomoto et al. found an increase in NF-κB activation in endothelial cells from H. pylori-infected versus uninfected individuals (29, 30). Therefore, we analyzed NF-κB activation in endothelial cells after H. pylori stimulation. We found that the more potent strains activated NF-κB DNA binding activity, indicating that these strains not only activate the endothelium to empty its prestored pool of adhesion molecules and chemokines but also induce it to synthesize these factors de novo. The induction of IL-8 mRNA by strain Hel 312 but not strain Hel 333 further strengthens this conclusion. These results demonstrate that the large difference in the capacity to activate endothelial cells among the H. pylori strains used was dependent on NF-κB activation. They also show that CagPAI is not the only factor that determines NF-κB DNA binding activity in endothelial cells, since CagPAI-positive strains failed to activate or only weakly activated the NF-κB complex.

In order to better define the factors mediating H. pylori activation of HUVEC, we also incubated HUVEC with formalin-fixed bacteria, but this treatment failed to induce any response (data not shown). However, when we used H. pylori filtrates, some stimulatory capacity was found, suggesting that a secreted or shed bacterial product(s) may contribute to endothelial cell stimulation. The secreted factor is probably a protein, since heat treatment at 85°C for 30 min completely inactivated the stimulatory effect in the filtrates and since previous observations showed that H. pylori lipopolysaccharide is unable to stimulate endothelial cells in this manner (M. Innocenti, unpublished observations). Several purified H. pylori proteins (i.e., urease, HP-NAP, Hsp60, and HpaA) as well as a whole-MP preparation did not activate endothelial cells. Still, the effect of H. pylori on endothelial cells seems to be direct, since neutralization of TNF-α in the cultures did not influence the ability of H. pylori to activate HUVEC. Taken together, these results indicate that an as-yet-unidentified secreted or shed protein(s) produced in different amounts by different H. pylori isolates contributes to human endothelial cell activation. The reason for the relatively poor activation of H. pylori filtrates compared to H. pylori bacteria may be that binding by H. pylori to HUVEC concentrates bacterial products close to endothelial cells, so that the actual concentration in the microenvironment will then be much higher than that in the filtrates. Further studies will be performed to try to identify the still unknown factor(s) involved in the activation of endothelial cells.

In conclusion, we have shown that several, but not all, H. pylori strains are able to activate endothelial cells to express the adhesion molecules VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin and to secrete neutrophil-recruiting chemokines. Variations in the expression of CagPAI, Lewis antigens, BabA, and VacA could not completely explain the ability of H. pylori to stimulate endothelial cells, and neither did the clinical status of the strain donors. Our results suggest that endothelial cells are actively involved in the continuous recruitment of neutrophils to H. pylori-infected gastric mucosa and may therefore also contribute to tissue damage and ulcer formation. One or several as-yet-uncharacterized H. pylori proteins may contribute to endothelial cell activation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Camilla Johansson and Kerstin Andersson for excellent technical assistance and Ingrid Bölin as well as AstraZeneca for kindly providing the purified proteins used in this study. We are grateful to Lars Engstrand for valuable help with CagPAI characterizations.

This study was supported by grants from Vetenskapsrådet (grant 16X-13428), the Faculty of Medicine at Göteborg University, Kungliga och Hvitfeldska Överskottsfonden, Socialstyrelsen, Rådman och Fru Ernst Collianders Stiftelse för Välgörande Ändamål, Magn. Bergwalls Stiftelse, Willhelm och Martina Lundgrens Vetenskapsfond, and the Strategic Research Foundation.

Editor: R. N. Moore

REFERENCES

- 1.Aihara, M., D. Tsuchimoto, H. Takizawa, A. Azuma, H. Wakebe, Y. Ohmoto, K. Imagawa, M. Kikuchi, N. Mukaida, and K. Matsushima. 1997. Mechanisms involved in Helicobacter pylori-induced interleukin-8 production by a gastric cancer cell line, MKN45. Infect. Immun. 65:3218-3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albelda, S. M., C. W. Smith, and P. A. Ward. 1994. Adhesion molecules and inflammatory injury. FASEB J. 8:504-512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atherton, J. C., T. L. Cover, R. J. Twells, M. R. Morales, C. J. Hawkey, and M. J. Blaser. 1999. Simple and accurate PCR-based system for typing vacuolating cytotoxin alleles of Helicobacter pylori. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2979-2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baeuerle, P. A., and V. R. Baichwal. 1997. NF-kappa B as a frequent target for immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory molecules. Adv. Immunol. 65:111-137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baggiolini, M. 1998. Chemokines and leukocyte traffic. Nature 392:565-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blaser, M. J. 1995. The role of Helicobacter pylori in gastritis and its pro-gression to peptic ulcer disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 9:27-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blaser, M. J., and J. Parsonnet. 1994. Parasitism by the “slow” bacterium Helicobacter pylori leads to altered gastric homeostasis and neoplasia. J. Clin. Investig. 94:4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boggemeyer, E., T. Stehle, U. E. Schaible, M. Hahne, D. Vestweber, and M. M. Simon. 1994. Borrelia burgdorferi upregulates the adhesion molecules E-selectin, P-selectin, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 on mouse endothelioma cells in vitro. Cell Adhes. Commun. 2:145-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolin, I., H. Lonroth, and A. M. Svennerholm. 1995. Identification of Helicobacter pylori by immunological dot blot method based on reaction of a species-specific monoclonal antibody with a surface-exposed protein. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:381-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns, M. J., T. J. Sellati, E. I. Teng, and M. B. Furie. 1997. Production of interleukin-8 (IL-8) by cultured endothelial cells in response to Borrelia burgdorferi occurs independently of secreted IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha and is required for subsequent transendothelial migration of neutrophils. Infect. Immun. 65:1217-1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Busam, K., C. Gieringer, M. Freudenberg, and H. P. Hohmann. 1992. Staphylococcus aureus and derived exotoxins induce nuclear factor κB-like activity in murine bone marrow macrophages. Infect. Immun. 60:2008-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Celik, J., B. Su, U. Tiren, Y. Finkel, A. C. Thoresson, L. Engstrand, B. Sandstedt, S. Bernander, and S. Normark. 1998. Virulence and colonization-associated properties of Helicobacter pylori isolated from children and adolescents. J. Infect. Dis. 177:247-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, C. C., and A. M. Manning. 1995. Transcriptional regulation of endothelial cell adhesion molecules: a dominant role for NF-kappa B. Agents Actions Suppl. 47:135-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins, T., M. A. Read, A. S. Neish, M. Z. Whitley, D. Thanos, and T. Maniatis. 1995. Transcriptional regulation of endothelial cell adhesion molecules: NF-kappa B and cytokine-inducible enhancers. FASEB J. 9:899-909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cover, T. L. 1997. Commentary: Helicobacter pylori transmission, host factors, and bacterial factors. Gastroenterology 113:S29-S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crabtree, J. E., A. Covacci, S. M. Farmery, Z. Xiang, D. S. Tompkins, S. Perry, I. J. Lindley, and R. Rappuoli. 1995. Helicobacter pylori induced interleukin-8 expression in gastric epithelial cells is associated with CagA positive phenotype. J. Clin. Pathol. 48:41-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crabtree, J. E., S. M. Farmery, I. J. Lindley, N. Figura, P. Peichl, and D. S. Tompkins. 1994. CagA/cytotoxic strains of Helicobacter pylori and interleukin-8 in gastric epithelial cell lines. J. Clin. Pathol. 47:945-950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crabtree, J. E., Z. Xiang, I. J. Lindley, D. S. Tompkins, R. Rappuoli, and A. Covacci. 1995. Induction of interleukin-8 secretion from gastric epithelial cells by a cagA negative isogenic mutant of Helicobacter pylori. J. Clin. Pathol. 48:967-969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dengler, T. J., M. J. Raftery, M. Werle, R. Zimmermann, and G. Schonrich. 2000. Cytomegalovirus infection of vascular cells induces expression of pro-inflammatory adhesion molecules by paracrine action of secreted interleukin-1beta. Transplantation 69:1160-1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunn, B. E., G. P. Campbell, G. I. Perez-Perez, and M. J. Blaser. 1990. Purification and characterization of urease from Helicobacter pylori. J. Biol. Chem. 265:9464-9469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dyer, R. B., C. R. Collaco, D. W. Niesel, and N. K. Herzog. 1993. Shigella flexneri invasion of HeLa cells induces NF-kappa B DNA-binding activity. Infect. Immun. 61:4427-4433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellmerich, S., N. Djouder, M. Scholler, and J. P. Klein. 2000. Production of cytokines by monocytes, epithelial and endothelial cells activated by Streptococcus bovis. Cytokine 12:26-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans, D. J., Jr., D. G. Evans, S. S. Kirkpatrick, and D. Y. Graham. 1991. Characterization of the Helicobacter pylori urease and purification of its subunits. Microb. Pathog. 10:15-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galdiero, M., A. Folgore, M. Molitierno, and R. Greco. 1999. Porins and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Salmonella typhimurium induce leucocyte transmigration through human endothelial cells in vitro. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 116:453-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Go, M. F. 1997. What are the host factors that place an individual at risk for Helicobacter pylori-associated disease? Gastroenterology 113:S15-S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamlet, A., A. C. Thoreson, O. Nilsson, A. M. Svennerholm, and L. Olbe. 1999. Duodenal Helicobacter pylori infection differs in cagA genotype between asymptomatic subjects and patients with duodenal ulcers. Gastroenterology 116:259-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hatz, R. A., G. Rieder, M. Stolte, E. Bayerdorffer, G. Meimarakis, F. W. Schildberg, and G. Enders. 1997. Pattern of adhesion molecule expression on vascular endothelium in Helicobacter pylori-associated antral gastritis. Gastroenterology 112:1908-1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Innocenti, M., A. M. Svennerholm, and M. Quiding-Järbrink. 2001. Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharides preferantially induce CXC chemokine production in human monocytes. Infect. Immun. 69:3800-3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isomoto, H., M. Miyazaki, Y. Mizuta, F. Takeshima, K. Murase, K. Inoue, K. Yamasaki, I. Murata, T. Koji, and S. Kohno. 2000. Expression of nuclear factor-kappaB in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric mucosa detected with southwestern histochemistry. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 35:247-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isomoto, H., Y. Mizuta, M. Miyazaki, F. Takeshima, K. Omagari, K. Murase, T. Nishiyama, K. Inoue, I. Murata, and S. Kohno. 2000. Implication of NF-kappaB in Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 95:2768-2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaplanski, G., N. Teysseire, C. Farnarier, S. Kaplanski, J. C. Lissitzky, J. M. Durand, J. Soubeyrand, C. A. Dinarello, and P. Bongrand. 1995. IL-6 and IL-8 production from cultured human endothelial cells stimulated by infection with Rickettsia conorii via a cell-associated IL-1 alpha-dependent pathway. J. Clin. Investig. 96:2839-2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaukoranta-Tolvanen, S. S., T. Ronni, M. Leinonen, P. Saikku, and K. Laitinen. 1996. Expression of adhesion molecules on endothelial cells stimulated by Chlamydia pneumoniae. Microb. Pathog. 21:407-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keates, S., Y. S. Hitti, M. Upton, and C. P. Kelly. 1997. Helicobacter pylori infection activates NF-kappa B in gastric epithelial cells. Gastroenterology 113:1099-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klein, C. L., F. Bittinger, H. Kohler, M. Wagner, M. Otto, I. Hermanns, and C. J. Kirkpatrick. 1995. Comparative studies on vascular endothelium in vitro. 3. Effects of cytokines on the expression of E-selectin, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 by cultured human endothelial cells obtained from different passages. Pathobiology 63:83-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kopp, E. B., and S. Ghosh. 1995. NF-kappa B and rel proteins in innate immunity. Adv. Immunol. 58:1-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krull, M., C. Dold, S. Hippenstiel, S. Rosseau, J. Lohmeyer, and N. Suttorp. 1996. Escherichia coli hemolysin and Staphylococcus aureus alpha-toxin potently induce neutrophil adhesion to cultured human endothelial cells. J. Immunol. 157:4133-4140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luscinskas, F. W., M. I. Cybulsky, J. M. Kiely, C. S. Peckins, V. M. Davis, and M. A. Gimbrone, Jr. 1991. Cytokine-activated human endothelial monolayers support enhanced neutrophil transmigration via a mechanism involving both endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecule-1 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1. J. Immunol. 146:1617-1625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manning, A., and D. C. Anderson. 1994. Transcription factor NF-kB: an emerging regulator of inflammation. Ann. Rep. Med. Chem. 29:235-244. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marshall, D. G., S. O. Hynes, D. C. Coleman, C. A. O'Morain, C. J. Smyth, and A. P. Moran. 1999. Lack of a relationship between Lewis antigen expression and cagA, CagA, vacA and VacA status of Irish Helicobacter pylori isolates. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 24:79-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Molestina, R. E., R. D. Miller, A. B. Lentsch, J. A. Ramirez, and J. T. Summersgill. 2000. Requirement for NF-κB in transcriptional activation of monocyte chemotactic protein 1 by Chlamydia pneumoniae in human endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 68:4282-4288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Donnell, J., B. Mille-Baker, and M. Laffan. 2000. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells differ from other endothelial cells in failing to express ABO blood group antigens. J. Vasc. Res. 37:540-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Philpott, D. J., S. Yamaoka, A. Israel, and P. J. Sansonetti. 2000. Invasive Shigella flexneri activates NF-kappa B through a lipopolysaccharide-dependent innate intracellular response and leads to IL-8 expression in epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 165:903-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryan, K. A., A. P. Moran, S. O. Hynes, T. Smith, D. Hyde, C. A. O'Morain, and M. Maher. 2000. Genotyping of cagA and vacA, Lewis antigen status, and analysis of the poly-(C) tract in the alpha(1,3)-fucosyltransferase gene of Irish Helicobacter pylori isolates. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 28:113-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakagami, T., M. Dixon, J. O'Rourke, R. Howlett, F. Alderuccio, J. Vella, T. Shimoyama, and A. Lee. 1996. Atrophic gastric changes in both Helicobacter felis and Helicobacter pylori infected mice are host dependent and separate from antral gastritis. Gut 39:639-648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharma, S. A., M. K. Tummuru, M. J. Blaser, and L. D. Kerr. 1998. Activation of IL-8 gene expression by Helicobacter pylori is regulated by transcription factor nuclear factor-kappa B in gastric epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 160:2401-2407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simoons-Smit, I. M., B. J. Appelmelk, T. Verboom, R. Negrini, J. L. Penner, G. O. Aspinall, A. P. Moran, S. F. Fei, B. S. Shi, W. Rudnica, A. Savio, and J. de Graaff. 1996. Typing of Helicobacter pylori with monoclonal antibodies against Lewis antigens in lipopolysaccharide. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2196-2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soderquist, B., J. Kallman, H. Holmberg, T. Vikerfors, and E. Kihlstrom. 1998. Secretion of IL-6, IL-8 and G-CSF by human endothelial cells in vitro in response to Staphylococcus aureus and staphylococcal exotoxins. APMIS 106:1157-1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tekstra, J., H. Beekhuizen, J. S. Van De Gevel, I. J. Van Benten, C. W. Tuk, and R. H. Beelen. 1999. Infection of human endothelial cells with Staphylococcus areus induces the production of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) and monocyte chemotaxis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 117:489-495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thoreson, A. C., A. Hamlet, J. Celik, M. Bystrom, S. Nystrom, L. Olbe, and A. M. Svennerholm. 2000. Differences in surface-exposed antigen expression between Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from duodenal ulcer patients and from asymptomatic subjects. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3436-3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Doorn, L. J., C. Figueiredo, R. Rossau, G. Jannes, M. van Asbroek, J. C. Sousa, F. Carneiro, and W. G. Quint. 1998. Typing of Helicobacter pylori vacA gene and detection of cagA gene by PCR and reverse hybridization. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1271-1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vane, R., E. Anggard, and M. Botting. 1990. Regulatory functions of the vascular endothelium. N. Engl. J. Med. 323:27-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wagner, D. D. 1993. The Weibel-Palade body: the storage granule for von Willebrand factor and P-selectin. Thromb. Haemostasis 70:105-110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weibel, E., and G. E. Palade. 1964. New cytoplasmatic components in arterial endothelia. J. Cell Biol. 23:101-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weiss, T. L., S. E. Selleck, M. Reusch, and B. U. Wintroub. 1990. Serial subculture and relative transport of human endothelial cells in serum-free, defined conditions. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. 26:759-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamaoka, Y., M. Kita, T. Kodama, N. Sawai, T. Tanahashi, K. Kashima, and J. Imanishi. 1998. Chemokines in the gastric mucosa in Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut 42:609-617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zheng, P. Y., J. Hua, K. G. Yeoh, and B. Ho. 2000. Association of peptic ulcer with increased expression of Lewis antigens but not cagA, iceA, and vacA in Helicobacter pylori isolates in an Asian population. Gut 47:18-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]