Abstract

During the natural aging process the immune system undergoes many alterations. In particular, both the CD4 and CD8 T-cell compartments become compromised, and these changes have serious implications for the capacity of the elderly to control infection. As a result, the elderly are more susceptible to many infectious diseases, including primary infection and reactivation of latent infections. In this study we addressed the capacity of old mice to control an infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis and to characterize the mechanism by which old mice, paradoxically, can express a transient early resistance to infection. This resistance was shown to be associated with the presence of CD8 T cells within the lungs that were capable of secreting gamma interferon, as illustrated by the demonstration that early resistance was lost in aged CD8 gene-disrupted mice. These studies therefore show that, despite a documented decline in general CD8 T-cell responsiveness in the elderly, a subset of CD8 T cells is an important early mediator of protection in the lungs of old mice that have been infected with M. tuberculosis.

The elderly are at increased risk from many infectious diseases, among which respiratory infections such as pneumonia, influenza, and tuberculosis are particularly prominent (3, 22, 32, 39; see also http://www.who.int/gtb/publications). This increased susceptibility of the elderly to infection has been attributed to several age-related defects in acquired immunity (6, 12, 13, 25, 28). CD4 T cells from the elderly express several cell surface markers that are characteristic of memory cells (CD44hi, CD45RBlo, and Mel-14lo) (1, 34), and expansion of the memory T-cell pool at the expense of naïve T cells may underlie the reduced ability of the host to respond to new antigenic challenge. The predominance of memory cells is not the only alteration that is thought to impact immunity to infection in the elderly. Naïve CD4 T cells from old mice produce less interleukin-2 (IL-2) in response to antigen (15), and many of the less-than-optimal immune responses in the elderly have been attributed to the loss of this cytokine. Alterations in the CD8 T-cell subset have also been well documented. CD8 T cells undergo clonal expansion during the natural aging process (19, 27), and as much as 70% of the CD8 T-cell pool can be made up of a single clone (2). Constant exposure to an endogenous viral antigen is thought to drive these clonal populations (18). That these cells have expanded to an end point is supported by the documented increase in CD8 T cells that fail to express the costimulatory molecule CD28 (2, 23). The biological relevance of these CD28− CD8 T cells is not well understood; however, the presence of CD28− CD8 T cells can be correlated to increased susceptibility to influenza (14).

Experimental models that directly address immunity to infection support the hypothesis that the failing T-cell response in old mice is related to the increased susceptibility to both primary infection and reactivation of a latent infection. Old mice are more susceptible to influenza, which correlates to a delay in the kinetics of CD8 cytotoxic T-cell (CTL) activity and also a reduction in the capacity to produce IL-2 (5, 12). Both cellular proliferation and CTL responses to varicella-zoster virus are also reduced in the elderly (7, 16). We have previously shown that the susceptibility of old mice to an intravenous infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis is associated with a delayed influx of CD4 T cells into the spleen (25).

Despite these well-documented insufficiencies in the aging immune system, several studies have also demonstrated that old mice possess enhanced innate (or preimmune) immunity to several pathogens (17, 21). Although these responses are often insufficient to eradicate a pathogen, there is evidence that immune responses in old mice may at least be capable of limiting tissue damage (6, 17), an event which may be particularly important within the aging lung.

The elderly population has been predicted to substantially increase to 2 billion people by 2050 (www.who.int/ageing/global), and with such a significant expansion of the elderly around the world there is an increasing need for vaccine development that can protect older individuals from infectious diseases. Despite the fact that the failing T-cell response is frequently cited as a reason that the elderly are more susceptible to infectious diseases, the vaccines that are recommended and used for the elderly are designed to stimulate these same cells. It is of no surprise, therefore, that many vaccine protocols fail (32, 39). It is necessary to identify alternative protective mechanisms that remain functional in the elderly that can be targeted by vaccines to better protect this population against infectious diseases.

In this regard, we have previously explained that old mice express a transient early resistance to a pulmonary infection with M. tuberculosis (9). The identification of the mechanism by which this is mediated may uncover novel immune effector functions in old mice that could potentially be manipulated by a vaccine to protect old mice against infection. In this study we demonstrate that the expression of early resistance to infection with M. tuberculosis was associated with the presence of CD8 T cells within the lungs of old mice and that cells of this phenotype were a major source of gamma interferon (IFN-γ). Confirmation that CD8 T cells were directly involved in the expression of this early resistance was demonstrated by studies that showed that this early resistance was lost in aged CD8 gene-disrupted mice. These studies therefore identify the CD8 T-cell population as important effector cells during the early course of M. tuberculosis infection in old mice. Targeting this population may be an alternative strategy in the design of vaccines that protect the elderly against infectious diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Specific-pathogen-free female 6- to 8-week-old C57BL/6, C57BL/6-Cd8a, or BALB/c mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine). Aging mice were kept in-house for 18 months and maintained with sterile water, bedding, and chow. B6D2/F1 mice were purchased from the Trudeau Institute animal breeding facility, Saranac Lake, N.Y, at 24 months of age. Infected mice were kept in biohazard facilities (biosafety level 3). The specific-pathogen-free nature of the mouse colonies was demonstrated by testing sentinel animals, which were shown to be negative for 12 known mouse pathogens. All procedures carried out were approved by the Colorado State University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Bacterial infections.

M. tuberculosis Erdman was originally obtained from the Trudeau Mycobacteria Collection, Saranac Lake, N.Y. Bacteria were grown in Proskauer-Beck liquid medium containing 0.05% Tween 80 to mid-log phase and then frozen in aliquots at −70°C until needed. Mice were infected via the respiratory route with a low dose of bacteria. Briefly, the nebulizer compartment of an airborne-infection apparatus (Middlebrook, Terre Haute, Ind.) was filled with a suspension of bacteria resulting in the delivery of 50 to 100 viable bacteria per lung during a 30 min exposure. The number of viable bacteria in the lung was determined at various time points by culturing serial dilutions of whole-organ homogenates onto Middlebrook 7H11 agar (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) and counting bacterial colonies after 21 days of incubation at 37°C. The data were expressed as the log10 value of the mean number of bacteria recovered per organ (n = 4 animals). For all experiments presented the initial inoculum was between 50 and 100 CFU, as determined by culturing lung homogenates 1 day postinfection. No significant differences in bacterial uptake were observed between any of the experimental groups. Old mice were carefully examined prior to infection or during necropsy, and any evidence of tumors or other age-associated diseases resulted in mice being removed from the study. Throughout each experiment, basic immunological data (percentages of T, B, CD4, and CD8 cells) were also obtained from each mouse. Mice that expressed unusual immune parameters (such as skewed B-cell/T-cell ratios) that were not reproducible within the experimental group were discarded from the study. To ensure that data from at least four mice per group were reported at each time point, and to allow for the exclusion of mice from the study where necessary, additional old mice were incorporated into each experiment.

Histological analysis.

The right caudal lung lobe was collected from each mouse and inflated with, and stored in, 10% neutral buffered formalin. Tissues were prepared and sectioned to allow the maximum surface area of each lobe to be seen. Tissue was stained with hematoxylin and eosin to determine granuloma formation. Tissues were examined by a qualified veterinary pathologist. Figures shown are representative of four individual sections.

Isolation of cells from infected lungs.

Mice were euthanized, and the pulmonary cavity was opened. The lung was cleared of blood by perfusion through the pulmonary artery with 10 ml of saline containing heparin (50 U/ml; Sigma, St Louis, Mo.). Lungs were removed from the pulmonary cavity and placed in cold Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Life Technologies, Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.). After removing the connective tissue and trachea, the lungs were disrupted using sterile razor blades and incubated for 30 min at 37°C in a final volume of 2 ml of DMEM containing collagenase XI (0.7 mg/ml; Sigma) and type IV bovine pancreatic DNase (30 μg/ml; Sigma). Then, 10 ml of DMEM was added to stop the action of the enzyme. Digested lungs were then gently dispersed through a nylon screen and centrifuged at 300 × g. Remaining red blood cells were lysed using ACK lysis buffer (0.15 M NH4Cl, 1.0 mM KHCO3). Cells were resuspended in DMEM plus 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Gibco-BRL), 1% 1 M HEPES buffer (Sigma), 1% l-glutamine (200 nM; Sigma), and 2% modified Eagle medium-nonessential amino acids (100×; Sigma). The number of cells were counted using a hemocytometer and the absolute number of cells per lung calculated.

Flow cytometry.

Cells from the lung were obtained from each individual mouse and incubated with specific antibody (labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC], phycoerythrin [PE], peridinin chlorophyll-a protein [PerCP], or allophycocyanin [APC] at 25 μg/ml) for 30 min at 4°C and in the dark, which was followed by two washes in D-RPMI lacking biotin and phenol red (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, Calif.). Cells were analyzed on a Becton Dickinson (San Diego, Calif.) FACSCalibur, and data were analyzed using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). Lymphocytes were gated by forward and side scatter, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were characterized by the presence of specific fluorescence-labeled antibody. Cell surface markers analyzed were FITC-labeled NKG2A/C/E (clone 20d5) or CD16/32 (clone 2.4G2); PE-labeled anti-CD3ɛ (clone 145-2C11), Ly49A (clone A1), or CD69 (clone H1.2F3); PerCP-labeled anti-CD4 (clone RM4-5); and APC-labeled anti-CD8 (clone 53-6.7) or NK1.1 (clone C:PK136). Appropriate isotype control antibodies were included in each analysis. All antibodies were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, Calif.), unless stated otherwise. Measurement of intracellular IFN-γ was carried out by preincubating lung cells with a 0.1-μg/ml concentration of anti-CD3ɛ (clone 145-2C11) and a 1-μg/ml concentration of anti-CD28 (clone 37.51) in the presence of 3 μM monensin for 4 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells were stained with PE-anti-CD122 (clone TM-β1), PerCP-anti-CD44 (clone IM7), or APC-anti-CD8 (clone 53-6.7) prior to a permeabilization step, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Fix/Perm kit, Pharmingen). FITC-anti-IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2; Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.), or immunoglobulin G1 isotype control antibody (Caltag) was incubated with the cells for a further 30 min, and the cells were washed twice and resuspended in D-RPMI prior to analysis.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical difference was calculated using the Student t test and reported as not significant, significant (P < 0.05), or highly significant (P < 0.005).

RESULTS

Growth of M. tuberculosis in the lungs of young and old mice.

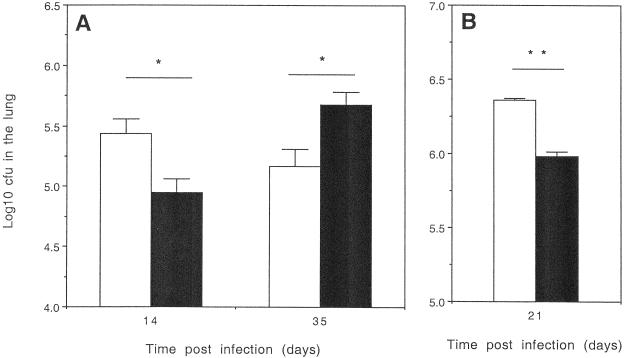

Young (3-month) or old (18-month) C57BL/6 mice were infected with a sublethal inoculum of M. tuberculosis Erdman via the respiratory route, and the course of infection followed. Lungs were isolated the following day, and the bacteria were enumerated to establish that equivalent numbers of bacteria were taken up in the different groups. No significant differences between the bacterial numbers within the lungs of old and young mice were found. Old mice showed a significantly greater capacity to control the growth of M. tuberculosis in the lungs after 14 days of infection, in comparison to the young mice (Fig. 1A). This early control, however, was not maintained, and the bacterial load subsequently increased to significantly higher levels than that seen in the young mice as the experiment continued. Similar results were also obtained with B6D2/F1 (9) and BALB/c mice (Fig. 1B). The capacity to reproduce our observations in several mouse strains indicates that the ability of old mice to express early resistance to M. tuberculosis infection is not restricted to a particular mouse strain but appears to be a previously unrecognized facet of the aging murine immune system.

FIG. 1.

Old mice express early resistance to infection with M. tuberculosis. (A) C57BL/6 mice were infected at 3 months (open bars) or 18 months (solid bars) of age with a low-dose aerosol inoculum of M. tuberculosis Erdman. Bacteria in the lung were enumerated at specific time points by culturing whole-organ homogenates on 7H11 agar and counting colonies after 21 days of incubation at 37°C. Data are expressed as the log10 CFU per lung from four mice per group (mean + standard error of the mean [error bars]). Figures are representative of three independent experiments. (B) BALB/c mice were infected at 3 months (open bars) or 18 months (closed bars) as described above. Data are representative of two independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using the Student t test and found to be significant (∗, P < 0.05) or highly significant (∗∗, P < 0.005) where indicated.

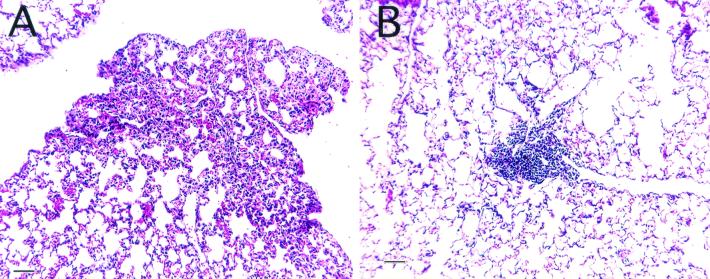

Immunopathology in the lungs of old and young mice.

Lung tissue was collected from old and young mice throughout the course of an experimental infection. After 14 days of infection with M. tuberculosis, the lungs of young mice had developed mild interstitial pneumonia (Fig. 2A). In contrast, small dense foci of perivascular or peribronchiolar lymphocytes surrounded by healthy lung tissue were present within the lungs of old mice (Fig. 2B). After 35 days of infection, the lungs of young and old mice developed characteristic lung lesions consisting of macrophages and lymphocytes (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Lung immunopathology of M. tuberculosis-infected mice. Lung tissue was collected from old and young mice that had been infected with M. tuberculosis 14 days earlier. Tissue was sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Young mice showed evidence of interstitial pneumonia (A), whereas old mice had relatively healthy lung structure with the occasional lymphocyte foci (B). Magnification, ×100; bar, 100 μm.

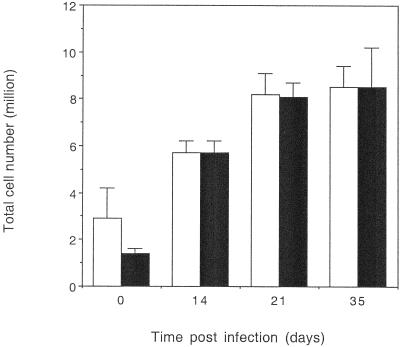

Lymphocyte influx into lungs of old and young mice.

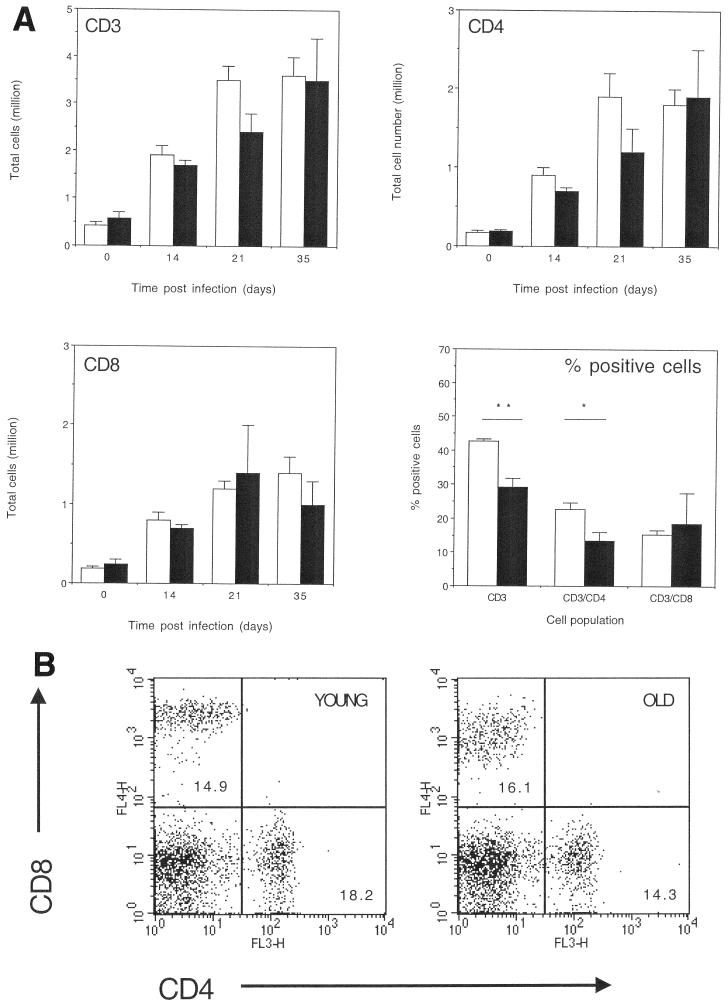

To identify the mechanism by which old mice could reduce the bacterial load in the lungs we first analyzed the cell populations that entered the lung over the first month of infection. Both young and old mice recruited equivalent numbers of cells into the lung throughout the course of the infection (Fig. 3). Old mice showed a delay in the proportion of T lymphocytes (Fig. 4) in the lungs. Analysis of T-cell subsets showed that old mice also had a delay in the proportion of CD4 T lymphocytes (Fig. 4) in the lungs, as we might predict based on our previous observations in the intravenous model of infection (25). An unexpected finding was that the proportion of CD8 T cells in the lungs of old mice infected with M. tuberculosis was equal to that observed in the young mouse control group (Fig. 4). In fact, during the course of numerous experiments we observed equivalent or often increased proportions of CD8 T cells within the lungs of old mice 15 days postinfection with M. tuberculosis (data not shown), an event which was again routinely observed in several different mouse strains. Analysis of the absolute number of CD3, CD4, and CD8 (Fig. 4) populations within the lungs of old and young mice showed a similar trend, with fewer CD3 and CD4 T cells within the lungs of old mice.

FIG. 3.

Total cell numbers within the lungs of M. tuberculosis-infected mice. Lung cells were isolated from young (open bars) or old (solid bars) M. tuberculosis-infected mice. Lung cells were resuspended in culture medium and counted using a hemocytometer, and the total cell number for each individual lung was determined. Day 0 represents noninfected age-matched mice. The data are expressed as the mean + standard error of the mean (error bars) from four mice at each time point, and the results are representative of two independent experiments using C57BL/6 mice and one with BALB/c mice. Statistical significance was determined using the Student t test and was not significant at any time point.

FIG. 4.

(A) Cell populations within lungs of M. tuberculosis-infected mice. Lung cells from young (open bar) or old (solid bar) infected mice were isolated and labeled with fluorescent antibodies specific for CD3ɛ, CD4, or CD8 (day 0 represents noninfected age-matched mice). Data were acquired on a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur and analyzed using CellQuest software. Cells were identified according to their characteristic scatter profile on a dot plot depicting forward and side scatter and a gate placed around the lymphocyte population. T-cell populations were identified by positive staining with specific labeled fluorescent antibody. The percentage of each cell population that was within the lymphocyte gate was determined using dot plots and drawing quadrants on each plot to differentiate the specific labeled cell populations. Absolute numbers for each given population were calculated from the flow cytometry data and total cell counts. Data are expressed as the absolute numbers of CD3, CD4, or CD8 T cells within the lungs at 0, 14, 21, and 35 days postinfection or the percent CD3, CD4, or CD8 T cells after 21 days of infection. The data are expressed as the mean + standard error of the mean (error bars) from four mice at each time point, and the figure is representative of two independent experiments using C57BL/6 mice and two using BALB/c mice. Statistical significance was determined using the Student t test and was found to be significant (∗, P < 0.05) or highly significant (∗∗, P < 0.005) where indicated. (B) Representative flow cytometry dot plots depict the percentage of cells labeled with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 from the lungs of old and young mice following an infection with M. tuberculosis.

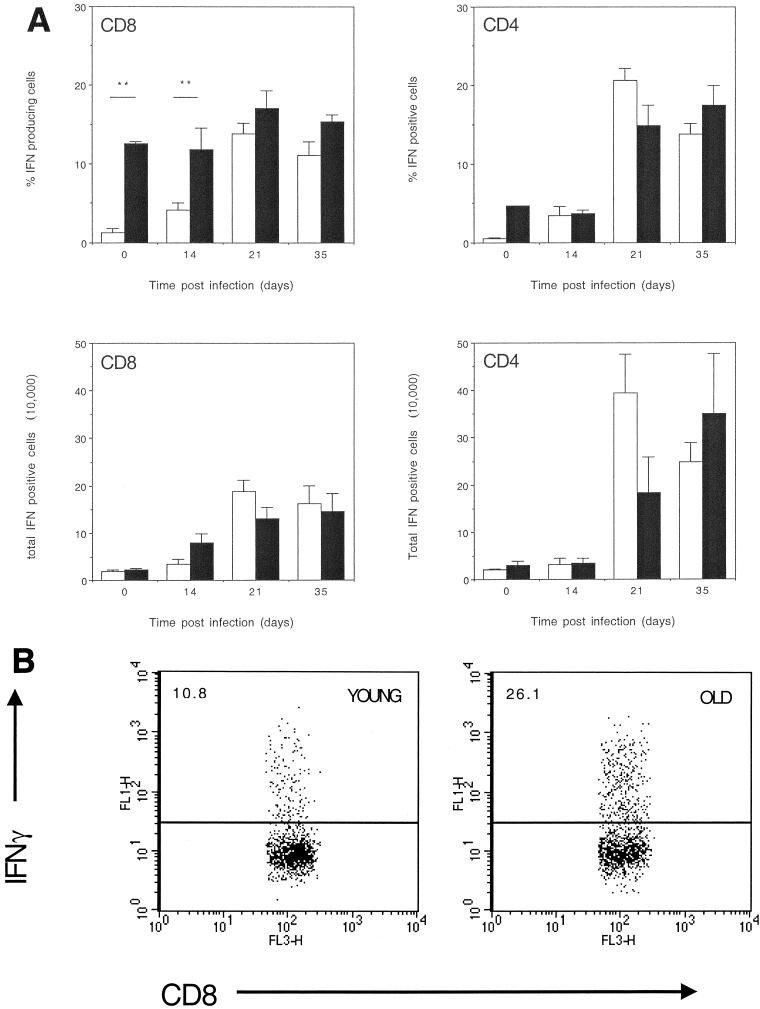

IFN-γ production by CD8 and CD4 T cells from infected lung.

To determine whether CD8 T cells within the lungs of old mice were capable of responding following an infection with M. tuberculosis we assessed the ability of these cells to produce IFN-γ. A significantly greater proportion of CD8 T cells from the lungs of old mice infected with M. tuberculosis were capable of producing IFN-γ than CD8 T cells from the lungs of young mice (Fig. 5) both prior to, and 14 days postinfection. In contrast, equivalent proportions of CD4 T lymphocytes from the lungs of old mice and young mice were able to produce IFN-γ (Fig. 5). Calculation of absolute numbers revealed that the number of CD8 IFN-γ-producing T lymphocytes increased in the lungs of old mice (Fig. 5) as early as 14 days postinfection with M. tuberculosis. No detectable expansion of CD4 IFN-γ-producing T lymphocytes was evident until 21 days postinfection in both old and young mice (Fig. 5), at which point it was apparent that old mice had fewer CD4 T cells within the lungs that were capable of producing IFN-γ.

FIG. 5.

(A) Intracellular IFN-γ production by T cells isolated from lungs of M. tuberculosis-infected mice. Lung cells from young (open bar) or old (solid bar) infected mice were cultured at a concentration of 5 × 106 cells/ml with anti-CD28 (1 μg/ml), anti-CD3 (0.1 μg/ml), and 3 μM monensin for 4 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Day 0 represents noninfected age-matched mice. Cells were labeled with fluorescent antibodies to CD8 or CD4, which was followed by a permeabilization step, and then cells were labeled with anti-IFN-γ. Cells were gated on CD8-positive labeled lymphocytes, and the percentage of CD8 T cells that labeled positive for IFN-γ was calculated. Alternatively, cells were gated on CD4-positivelabeled lymphocytes and the percentage of CD4 T cells labeled positive for IFN-γ was calculated. Data are expressed as the percentage of CD8 or CD4 T lymphocytes that produce IFN-γ (top panels) or the absolute number of CD8 or CD4 T lymphocytes that produce IFN-γ (bottom panels). The data are expressed as the mean + standard error of the mean (error bars) from four mice at each time point, and the figure is representative of two individual experiments using C57BL/6 mice and two using BALB/c mice. Statistical significance was determined using the Student t test and was found to be highly significant (∗∗, P < 0.005) where indicated. (B) Representative dot plots depicting the percentage of CD8 T cells producing IFN-γ are shown for young and old mice.

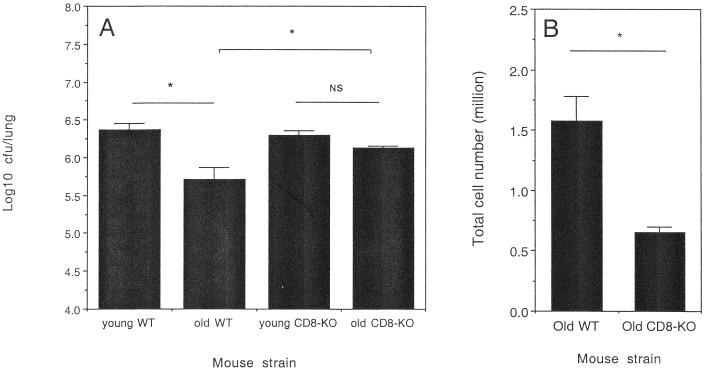

Old CD8 gene-disrupted mice do not express increased resistance to M. tuberculosis.

To directly confirm that CD8 T cells were involved in the transient early resistance to M. tuberculosis infection in the lungs of old mice, we infected old or young CD8 gene-disrupted mice by aerosol and compared the course of infection to that observed in old or young wild-type mice. As presented in Fig. 6A, old wild-type mice expressed the characteristic increased resistance 21 days postinfection. In contrast, old CD8 gene-disrupted mice lost the ability to express early resistance to M. tuberculosis in the lung, demonstrating the necessity for the presence of CD8 T cells for the expression of early resistance to infection. As we have previously demonstrated (11), the absence of CD8 T cells from the lungs of young mice did not influence the early course of infection, therefore demonstrating that the CD8 T cell plays a unique role within the lungs of old mice. Evaluation of IFN-γ-producing cells within the lungs of the old mice demonstrated that old wild-type mice had significantly more cells within the lungs that were capable of producing IFN-γ than old CD8 gene-disrupted mice (Fig. 6B) during the experimental time point when transient resistance to infection was normally expressed.

FIG. 6.

Control of M. tuberculosis infection by wild-type and CD8 gene-disrupted mice. (A) Young C57BL/6 (young WT), old C57BL/6 (old WT), young CD8 gene-disrupted (young CD8-KO), and old CD8 gene-disrupted (old CD8-KO) mice were infected with a low-dose aerosol inoculum of M. tuberculosis Erdman. Bacteria in the lung were enumerated after 21 days of infection by culturing whole-organ homogenates on 7H11 agar and counting colonies after 21 days of incubation at 37°C. Data are expressed as the log10 CFU per lung from four mice per group (mean + standard error of the mean [error bars]) and are representative of two independent experiments. (B) Lungs cells from old WT or old CD8-KO mice that had been infected for 21 days were cultured at a concentration of 5 × 106 cells/ml with anti-CD28 (1 μg/ml), anti-CD3 (0.1 μg/ml), and 3 μM monensin for 4 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells were labeled with fluorescent antibodies against CD8 or CD4, which was followed by a permeabilization step, and then cells were labeled with anti-IFN-γ. The percent cells that were capable of producing IFN-γ was calculated and converted to absolute numbers of cells that produced IFN-γ. Statistical significance was determined using the Student t test and was found to be significant (∗, P < 0.05) or not significant (NS) where indicated.

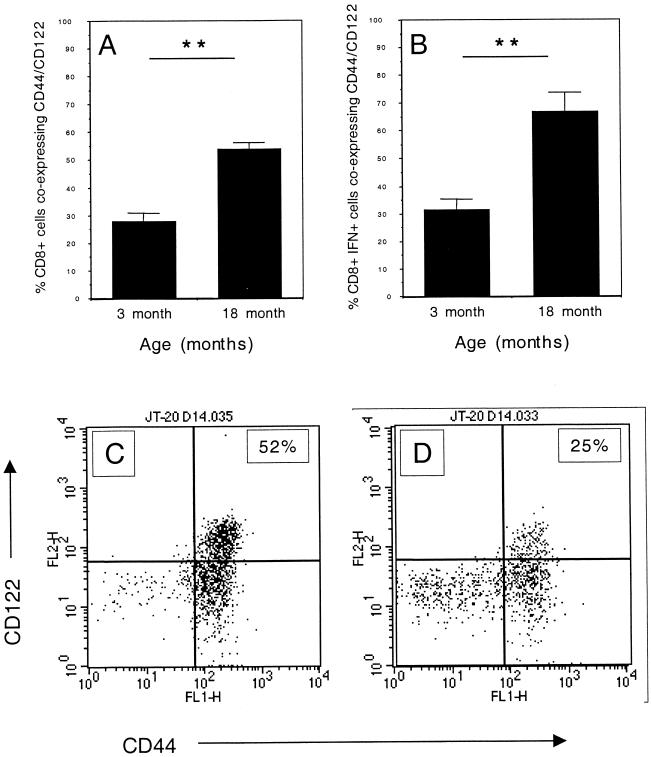

CD8 T cells harvested from the lungs of old mice coexpress CD44 and CD122.

Rapid IFN-γ secretion has been previously documented in CD8 T cells from naïve old mice which also express high levels of the IL-15 receptor (CD122) (33). In addition, CD8 T cells which express CD44hi proliferate in response to early immune mediators such as type I interferon (IFN-I) (31). We hypothesized that the previously described CD122+ or CD44hi CD8 T cells were in fact the same population and that they would be responsible for the expression of early resistance in the lungs of old mice. CD8 T cells isolated from the lungs of old M. tuberculosis-infected mice were predominantly of the CD44hi CD122hi phenotype (Fig. 7A). A more detailed examination of IFN-γ-producing cells showed that the majority of IFN-γ+ CD8 T cells also expressed both CD44hi CD122hi (Fig. 7B). Absolute numbers reflected the same trend (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Expression of CD44 and CD122 on CD8 T cells isolated from lungs of M. tuberculosis-infected mice. Lung cells from mice that had been infected for 14 days were cultured at a concentration of 5 × 106 cells/ml with anti-CD28 (1 μg/ml), anti-CD3 (0.1 μg/ml), and 3 μM monensin for 4 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells were labeled with fluorescent antibody against CD8, CD122, and CD44. Cells were permeabilized and incubated with anti-IFN-γ. Lung cells were either gated on CD8 (A) or CD8 and IFN-γ (B). Data are expressed as the mean + standard error of the mean (error bars) from four individual mice. Representative dot plots from old (C) or young (D) mice are depicted which show the expression of CD44 and CD122 on CD8 T cells. The figure is representative of two individual experiments using C57BL/6 mice and one experiment using BALB/c mice. Statistical significance was determined using the Student t test and was found to be highly significant (∗∗, P < 0.005) where indicated.

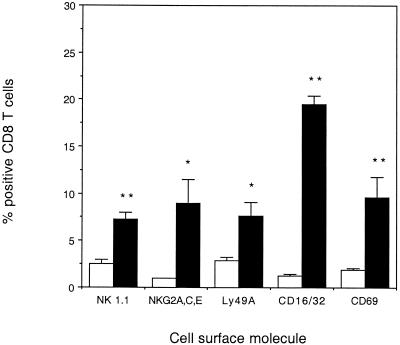

CD8 T cells harvested from the lungs of old mice expressed natural killer cell-associated receptors.

The expression of early resistance to infection with M. tuberculosis before acquired immunity is known to be generated in young mice (24) suggests that CD8 T cells from the lungs of old mice could be responding to infection with M. tuberculosis in a nonspecific manner. We therefore determined whether CD8 T cells isolated from the lungs of old mice expressed cell surface receptors that are associated with natural killer (NK) cell activity. Whereas very few CD8 T cells from the lungs of naïve young mice expressed NK-associated receptors, significantly more CD8 T cells from the lungs of naïve old mice expressed NK1.1, NKG2ACE, Ly49A, and CD16/32. Increased expression of the early activation molecule CD69 (Fig. 8) demonstrated that CD8 T cells within the lungs of old mice were also activated and could potentially respond to infection with M. tuberculosis in a nonspecific manner. CD8 T cells from the lungs of young mice expressed CD69 after 14 days of infection (data not shown), as has been previously demonstrated (29).

FIG. 8.

Expression of NK receptors on CD8 T cells isolated from lungs of naïve old and young mice. Lung cells from young (open bar) or old (solid bar) naïve mice were isolated and labeled with fluorescent antibodies specific for CD8 in combination with either NK1.1, NKG2ACE, Ly49A, CD16/32, or CD69. Data were acquired on a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur and analyzed using CellQuest software. Cells were identified according to their characteristic scatter profile on a dot plot depicting forward and side scatter and a gate placed around the lymphocyte population. The CD8 T-cell population was identified by positive staining with specific labeled fluorescent antibody. The percentage of CD8 T cells that were positive for NK receptors was determined using dot plots and drawing quadrants on each plot to differentiate the specific labeled cell populations. The data are expressed as the mean + standard error of the mean (error bars) from four mice. Statistical significance was determined using the Student t test and was found to be significant (∗ P < 0.05) or highly significant (∗∗, P < 0.005) where indicated.

DISCUSSION

This study sought to determine the basis for the previously documented expression of early resistance to M. tuberculosis seen in old mice (9). We demonstrate that the transient increase in host resistance in old mice infected by aerosol exposure with M. tuberculosis was highly associated with the presence of CD8 lymphocytes in the lungs at that time. These CD8 T cells were of the CD44hi CD122+ phenotype, expressed several NK-associated receptors, and had an increased capacity to secrete IFN-γ. We confirmed this association by infecting old CD8 gene-disrupted mice with M. tuberculosis and showed that in the absence of CD8 T cells, the expression of early resistance to M. tuberculosis was lost. This finding appears to be unique to old mice, as we have previously demonstrated that the absence of CD8 T cells does not influence the early control of M. tuberculosis in young mice (11, 36).

In young mice, the CD8 T-cell response is thought to be much more important in the control of chronic (36) or latent M. tuberculosis infection (38), and therefore the action of this T-cell population may not become apparent until much later in life. Despite this, CD8 T cells have been shown to produce IFN-γ (30) and to express CTL activity (29) during the acute phase of infection. Their action, however, is often preceded by a strong CD4 T-cell-mediated immune response. In old mice the CD4 T-cell response is delayed both in the intravenous model (25) and in the respiratory model of infection, as shown here. Old mice may therefore have developed an alternative CD8-mediated immune response that can compensate for the delayed influx of CD4 T cells into the lung. We demonstrate, however, that the eventual recruitment of CD4 T cells into the lungs of old mice is still not sufficient to limit the infection, and the bacterial load in the lungs of the aged mice gradually increased and eventually exceeded those seen in young mice.

Despite the transient nature of the mechanism we have described, old mice have clearly developed an alternative early mechanism for controlling bacterial growth within the lungs that not only compensates for the delayed recruitment of CD4 T cells into the lung but also results in enhanced control of bacterial growth. Indeed, analysis of infected lung tissue showed that the response within the lungs of old mice was different to that of young mice. Lung tissue from old mice that had been infected with M. tuberculosis presented with small foci of lymphocytic accumulations instead of the interstitial pneumonia normally seen in the lungs of young mice. The expression of early resistance to infection, or the capacity to limit tissue involvement, appears to be a characteristic of old mice (6, 17). This may be particularly relevant in the lung, where it has recently been demonstrated that CD8 memory T cells are capable of responding to unrelated antigens (heterologous immunity) and altering the immunopathology in this organ (8). This recent report also supports a role for nonspecific CD8 T-cell responses to infection within the lungs.

The mechanism by which CD8 T cells mediate the expression of early resistance to infection appears to be linked to their capacity to produce IFN-γ. Significantly more CD8 T cells isolated from the lungs of infected old mice were capable of producing IFN-γ than similar cells isolated from young mice. We also demonstrate that the total number of cells capable of producing IFN-γ was significantly reduced in old CD8 gene-disrupted mice at the time when early resistance to M. tuberculosis infection was lost. Interestingly, CD8 T cells isolated from the lungs of noninfected old mice were also capable of producing IFN-γ. This suggests that the CD8 T cells from old mice may indeed be part of a resident population within the lungs of old mice that can rapidly respond to an infection. This would account for their presence within the lungs despite the previously documented failure to recruit T-cell subsets to the spleens of old mice following an intravenous infection with M. tuberculosis (25, 26). What we also observed, however, was that while the absolute numbers of CD8 T cells were equally increased within the lungs of old and young mice after 14 days of infection, the number of IFN-γ-producing CD8 T cells within the lungs of old mice increased. The CD8 T cells isolated from the lungs of old mice therefore have properties different from those of cells harvested from young mice.

The CD8 T cells that were isolated from the lungs of old mice were also phenotypically different from the CD8 T cells from the lungs of young mice. Those CD8 T cells from the lungs of old mice that were also capable of producing IFN-γ could be further characterized by their bright expression of CD44 and the IL-15 receptor (CD122). This therefore identifies a specific cell phenotype within the lungs of old mice and will aid in the further characterization of their role during the expression of early resistance. CD8 T cells that express CD44 and CD122 have also been identified in naïve old mice and appear to have unique properties. CD8 CD122hi T cells from old mice have been shown to rapidly produce IFN-γ in response to stimulus (33), and it has been suggested that they may comprise an NK-like population, exhibiting increased tumor activity and rapid cytokine secretion much like the NK1.1 T cell (33). These properties could therefore be attributed to the CD8 T cells we have characterized within the lungs of old mice in this study and would account for their capacity to produce IFN-γ early in infection. We also demonstrate that CD8 T cells from the lungs of old naïve mice express an array of NK receptors, including NK1.1 and the activating and inhibiting receptor NKG2 (20) (the ligand for which is expressed in response to viral infection or stress) in further support of this hypothesis.

It has also been documented that CD8 CD44hi CD122+ T cells can be activated and expanded in response to stimuli such as IFN-I (4) or CpG DNA (35) in an IL-15-dependent manner (40). Here we demonstrate that an infectious agent, M. tuberculosis, could also induce the influx or expansion of the CD8 CD44hi CD122+ population within the lungs of old mice. That the stimulus for CD8 T cells in the lungs of old mice may be IFN-I is supported by previous studies from our group demonstrating that in the absence of IFN-I a moderate and transient exacerbation of infection was seen in young mice infected with M. tuberculosis (10). Whether the role of IFN-I in the lungs of old mice is enhanced, thus expanding this memory CD8 T-cell population further, is yet to be determined.

An important question that we have been unable to resolve in these studies is whether CD8 T cells within the lungs of old mice are responding to infection with M. tuberculosis in an antigen-specific manner. The mice used in these studies were housed in individual HEPA-filtered cages in a room that had no known exposure to mycobacteria, and therefore the potential for exposure to mycobacterial antigens throughout life was minimal. In addition, culture of splenocytes or total lung cells from old and young mice has not revealed any enhanced IFN-γ production in response to mycobacterial antigens (data not shown). We favor the hypothesis that CD8 T cells within the lungs of old mice are responding to infection with M. tuberculosis in a nonspecific manner, a hypothesis which is supported by our finding that CD8 T cells from naïve mice can produce IFN-γ and also express NK-associated molecules on their surface. Whether these CD8 T cells can be stimulated earlier in life to be responsive to mycobacterial antigens (and therefore extend the early resistance) is yet to be determined. Others have recently described a subset of CD8 memory T cells defined according to their expression of NK receptors (37), and so it is possible that mycobacterium-specific CD8 T cells generated earlier in life could be involved.

In summary, we have demonstrated that old mice express a transient early resistance to infection with M. tuberculosis that is highly associated with the presence of CD8 CD44hi CD122+ T cells capable of producing IFN-γ. These results demonstrate that old mice have developed an alternative immune response that can compensate for the delayed influx of CD4 T cells into the lung. CD8 T cells may therefore be an important cell population to consider when designing vaccines specifically to protect the elderly against infectious diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant AG-06946 and a Colorado State University College Research Council award (J.T.).

We thank Jason Brooks for his technical assistance.

Editor: S. H. E. Kaufmann

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrat, F., H. Haegel, A. Louise, S. Vincent-Naulleau, H.-J. Boulouis, T. Neway, R. Ceredig, and C. Pilet. 1995. Quantitative and qualitative changes in CD44 and MEL-14 expression by T cells in C57BL/6 mice during aging. Res. Immunol. 146:23-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batliwalla, F., J. Monteiro, D. Serrano, and P. K. Gregersen. 1996. Oligoclonality of CD8+ T cells in health and disease: aging, infection, or immune regulation? Hum. Immunol. 48:68-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beers, M. H., and R. Berkow (ed.). 2000. The Merck manual of geriatrics, 3rd ed., vol. 1. Merck Research Laboratories, Whitehouse Station, New Jersey.

- 4.Belardelli, F., M. Ferrantini, S. M. Santini, S. Baccarini, E. Proietti, M. P. Colombo, J. Sprent, and D. F. Tough. 1998. The induction of in vivo proliferation of long-lived CD44hi CD8+ T cells after the injection of tumor cells expressing IFN-α1 into syngeneic mice. Cancer Res. 58:5795-5802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bender, B. S., M. P. Johnson, and P. A. Small. 1991. Influenza in senescent mice: impaired cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity is correlated with prolonged infection. Immunology 72:514-519. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bender, B. S., S. F. Taylor, D. S. Zander, and R. Cottey. 1995. Pulmonary immune response of young and aged mice after influenza challenge. J. Lab. Clin. Investig. 126:169-177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berger, R., G. Florent, and M. Just. 1981. Decrease of the lymphoproliferative response to Varicella-zoster virus antigen in the aged. Infect. Immun. 32:24-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, H. D., A. E. Fraire, I. Joris, M. A. Brehm, R. M. Welsh, and L. K. Selin. 2001. Memory CD8+ T cells in heterologous antiviral immunity and immunopathology in the lung. Nat. Immunol. 2:1067-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper, A. M., J. E. Callahan, J. P. Griffin, A. D. Roberts, and I. M. Orme. 1995. Old mice are able to control low-dose aerogenic infections with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 63:3259-3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper, A. M., J. E. Pearl, J. V. Brooks, S. Ehlers, and I. M. Orme. 2000. Expression of the nitric oxide synthase 2 gene is not essential for early control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the murine lung. Infect. Immun. 68:6879-6882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Souza, C. D., A. M. Cooper, A. A. Frank, S. Ehlers, J. Turner, A. Bendelac, and I. M. Orme. 2000. A novel nonclassical β2-microglobulin-restricted mechanism influencing early lymphocyte accumulation and subsequent resistance to tuberculosis in the lung. Am. J. Resp. Cell Mol. Biol. 23:188-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Effros, R. B., and R. L. Walford. 1983. The immune response of aged mice to influenza: diminished T-cell proliferation, interleukin 2 production and cytotoxicity. Cell. Immunol. 81:298-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garg, M., W. Luo, A. M. Kaplan, and S. Bondad. 1996. Cellular basis of decreased immune responses to pneumococcal vaccines in aged mice. Infect. Immun. 64:4456-4462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goronzy, J. J., J. W. Fulbright, C. S. Crowson, G. A. Poland, W. M. O'Fallon, and C. M. Weyand. 2001. Value of immunological markers in predicting responsiveness to influenza vaccination in elderly individuals. J. Virol. 75:12182-12187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haynes, L., P.-J. Linton, S. M. Eaton, S. L. Tonkonogy, and S. L. Swain. 1999. Interleukin 2, but not other common γ chain-binding cytokines, can reverse the defect in generation of CD4 effector T cells from naive T cells of aged mice. J. Exp. Med. 190:1013-1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayward, A. R., and M. Herberger. 1987. Lymphocyte responses to Varicella zoster virus in the elderly. J. Clin. Immunol. 7:174-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson, L. L., G. W. Gibson, and P. C. Sayles. 1995. Preimmune resistance to Toxoplasma gondii in aged and young adult mice. J. Parasitol. 81:894-899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ku, C.-C., J. Kappler, and P. Marrack. 2001. The growth of very large CD8+ T cell clones in older mice is controlled by cytokines. J. Immunol. 166:2186-2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ku, C. C., B. Kotzin, J. Kappler, and P. Marrack. 1997. CD8+ T-cell clones in old mice. Immunol. Rev. 160:139-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanier, L. L. 2000. Turning on natural killer cells. J. Exp. Med. 191:1259-1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lovik, M., and R. J. North. 1985. Effect of aging on antimicrobial immunity: old mice display a normal capacity for generating protective T cells and immunologic memory response to infection with Listeria monocytogenes. J. Immunol. 135:3479-3486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niederman, M. S., and A. M. Fein. 1986. Pneumonia in the elderly. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2:241-268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nociari, M. M., W. Telford, and C. Russo. 1999. Postthymic development of CD28-CD8+ T cell subset: age-associated expansion and shift from memory to naive phenotype. J. Immunol. 162:3327-3335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orme, I. M. 1987. The kinetics of emergence and loss of mediator T lymphocytes acquired in response to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 138:293-298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orme, I. M., J. P. Griffin, A. D. Roberts, and D. N. Ernst. 1993. Evidence for a defective accumulation of protective T cells in old mice infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell. Immunol. 147:222-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orme, I. M., and A. D. Roberts. 1998. Changes in integrin/adhesion molecule expression, but not in the T-cell receptor repertoire, in old mice infected with tuberculosis. Mech. Age Dev. 105:19-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ricalton, N. S., C. Roberton, J. M. Norris, M. Rewers, R. F. Hammon, and B. L. Kotzin. 1998. Prevalence of CD8+ T-cell expansions in relation to age in healthy individuals. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. 53(Suppl. A):B196-B203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romero-Steiner, S., D. M. Musher, M. S. Cetron, L. B. Pais, J. E. Groover, A. E. Fiore, B. D. Plikaytis, and G. M. Carlone. 1999. Reduction in functional antibody activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae in vaccinated elderly individuals highly correlates with decreased IgG antibody avidity. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:281-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Serbina, N., C.-C. Liu, C. A. Scanga, and J. Flynn. 2000. CD8+ CTL from lungs of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected mice express perforin in vivo and lyse infected macrophages. J. Immunol. 165:353-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Serbina, N. V., and J. L. Flynn. 2001. CD8+ T cells participate in the memory immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 69:4320-4328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sprent, J., D. F. Tough, and S. Sun. 1997. Factors controlling the turnover of T memory cells. Immunol. Rev. 156:79-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stein, B. E. 1994. Vaccinating elderly people. Drugs Aging 5:242-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takayama, E., S. Seki, T. Ohkawa, K. Ami, Y. Habu, T. Yamaguchi, T. Tadakuma, and H. Hiraide. 2000. Mouse CD8+ CD122+ T cells with intermediate TCR increasing with age provide a source of early IFN-γ production. J. Immunol. 164:5652-5658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Timm, J. A., and M. L. Thoman. 1999. Maturation of CD4+ lymphocytes in the aged microenvironment results in a memory-enriched population. J. Immunol. 162:711-717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tough, D. F., P. Borrow, and J. Sprent. 1996. Induction of bystander T cell proliferation by viruses and type I interferon. Science 272:1947-1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turner, J., C. D. D'Souza, J. E. Pearl, P. Marietta, M. Noel, A. A. Frank, R. Appelberg, I. M. Orme, and A. M. Cooper. 2001. CD8- and CD95/95L-dependent mechanisms of resistance in mice with chronic pulmonary tuberculosis. Am. J. Resp. Cell Mol. Biol. 24:203-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ugolini, S., C. Arpin, N. Anfossi, T. Walzer, A. Cambiaggi, R. Forster, M. Lipp, R. E. M. Toes, C. J. Melief, J. Marvel, and E. Vivier. 2001. Involvement of inhibitory NKRs in the survival of a subset of memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2:430-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Pinxteren, L. A. H., J. P. Cassidy, B. H. C. Smedegaard, E. M. Agger, and P. Andersen. 2000. Control of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection is dependent on CD8 T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:3689-3698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Webster, R. G. 2000. Immunity to influenza in the elderly. Vaccine 18:1686-1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang, X., S. Sun, I. Hwang, D. F. Tough, and J. Sprent. 1998. Potent and selective stimulation of memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells in vivo by IL-15. Immunity 8:591-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]