Abstract

The gene region for biosynthesis of Shigella sonnei form I O polysaccharide (O-Ps) and flanking sequences, totaling >18 kb, was characterized by deletion analysis to define a minimal construct for development of Salmonella-based live vaccine vector strains. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) expression and DNA sequence studies of plasmid deletion derivatives indicated form I O-Ps expression from a 12.3-kb region containing a putative promoter and 10 contiguous open reading frames (ORFs), one of which is the transposase of IS630. A detailed biosynthetic pathway, consistent with the predicted functions of eight of the nine essential ORFs and the form I O-Ps structure, is proposed. Further sequencing identified partial IS elements (i.e., IS91 and IS630) and wzz upstream of the form I coding region and a fragment of aqpZ and additional full or partial IS elements (i.e., IS629, IS91, and IS911) downstream of this region. The stability of plasmid-based form I O-Ps expression was greater from low-copy vectors than from high-copy vectors and was enhanced by deletion of the downstream IS91 from plasmid inserts. Both core-linked (i.e., LPS) and non-core-linked (i.e., capsule-like) surface expression of form I O-Ps were detected by Western blotting and silver staining of polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis-separated Shigella and Escherichia coli extracts. However, salmonellae, which have a core that is chemically dissimilar to that of shigellae, expressed only non-core-linked surface-associated form I O-Ps. Finally, attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi live vaccine vector candidates, containing minimal-sized form I operon constructs, elicited immune protection in mice against virulent S. sonnei challenge, thereby supporting the promise of live, oral vaccines for the prevention of shigellosis.

It has been over 100 years since the discovery of Shiga's bacillus, yet shigellosis remains endemic in most areas of the world, including industrialized nations. An estimated 200 million people worldwide suffer from shigellosis, with more than 650,000 associated deaths annually (27). A recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate indicates the occurrence of over 440,000 annual shigellosis cases in the United States alone (32), approximately 80% of which are caused by Shigella sonnei. All virulent S. sonnei strains comprise a single serotype determined by form I O polysaccharide (O-Ps). This Ps is composed of a disaccharide repeating unit containing two unusual amino sugars, 2-amino-2-deoxy-l-altruronic acid (l-AltNAcA) and 2-acetamido-4-amino-2,4,6-trideoxy-d-galactose (4-n-d-FucNAc) (25). The genes encoding this O-Ps are novelly located on a 180-kb virulence plasmid (26), which also harbors the invasion genes (36). Virulent form I colonies are typically unstable and upon replating convert to rough colonies, termed form II, due primarily to spontaneous loss of the large virulence plasmid and the ensuing loss of form I O antigen.

Immunity to shigellae, acquired either by natural infection or volunteer challenge, is mediated largely by immune responses directed against the serotype-specific O-Ps (9, 10). This insight has led to the development of a variety of candidate vaccines containing Shigella O-Ps for oral or parenteral administration, including recombinant heterologous, live, bacterial carrier strains (3, 12, 18). In early recombinant vaccine efforts, the virulence plasmid of S. sonnei was transferred as part of a larger plasmid cointegrate to the attenuated vector Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi strain Ty21a (12). The resulting hybrid vaccine strain, 5076-1C, expressed S. sonnei O antigen as a lipid-linked surface Ps as well as S. enterica serovar Typhi 9,12 lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (37). Although not core linked, this form I Ps was immunogenic, (12) and oral immunization of volunteers with 5076-1C elicited protection against virulent S. sonnei oral challenge (3, 21, 40). However, the protection observed in volunteers was variable, presumably due to loss of the form I gene region from the large cointegrate plasmid in 5076-1C (17). Thus, further molecular studies are needed to stabilize the S. sonnei form I gene region in vaccine vector constructs.

Although the form I Ps-encoding locus has been studied in some detail previously (6, 24, 38, 42, 45), the biosynthetic pathway and minimal gene region needed for stable expression of O antigen have not been unambiguously defined. In this report we show through deletion and sequence analyses and LPS expression studies that the S. sonnei form I biosynthetic gene region comprises a 12.3-kb operon. A detailed biosynthetic pathway, based on DNA sequence analysis of this region and the known structure of form I O-Ps, is proposed. In addition, stable expression of form I Ps was observed from a low-copy plasmid and was associated with the removal of adjacent IS91, resulting in small, genetically stable form I gene region constructs. Finally, we report the development and preliminary animal testing of a live attenuated S. enterica serovar Typhi vaccine vector stably expressing form I Ps for protection against S. sonnei disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids utilized are described in Table 1. Wild-type S. sonnei strain 53G form I (i.e., 53GI), harboring the 180-kb virulence plasmid, was used for cloning studies and as a positive control for LPS analysis and immunoblot assays. Studies of plasmid-based form I O-Ps expression were performed in Escherichia coli strains HB101 or DH5α, S. enterica serovar Typhi strain Ty21a, and virulence plasmid-deficient S. sonnei strain 53G form II (i.e., 53GII).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strain | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | supE44 hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | 35 |

| HB101 | supE44 hsdS20 (rB−mB−) recA13 ara-14 proA2 lacY1 galk2 rpsL20 xyl-5 mtl-1 | 35 |

| S. enterica serovar Typhi Ty21a | galE ilvD viaB (Vi−) H2S− | 14 |

| S. sonnei | ||

| 53GI | Form I (phase I), virulent isolate | 26 |

| 53GII | Form II (phase II), avirulent variant | 26 |

| Plasmid | ||

| pGB-2 | pSC101 derivative, low-copy plasmid; Smr, Spcr | 7 |

| pBR325 | pBR322-derived plasmid; Cmr, Apr, Tcr | 4 |

| pUC18 | pBR322-derived cloning vector; Lac+, Apr | 41 |

| pHC79 | pBR322-derived cosmid; Apr, Tcr | 23 |

| pCVD551 | pHC79-derived cosmid; Cmr | Timothy McDaniel |

| pWR101 | S. sonnei form I-positive cosmid clone 19; Tcr | 26 |

| pWR102 | S. sonnei form I-positive cosmid clone 27; Tcr | 26 |

| pXG914 | 30-kb BamHI fragment of pWR101 cloned into pCVD551 cosmid; Cmr | This study |

| pXK68 | 15.7-kb HindIII fragment of pXG914 cloned into pBR325; Apr, Cmr | This study |

| pXK67 | 15.7-kb HindIII fragment of pXG914 cloned into pGB-2; Smr, Spcr | This study |

| pXK66 | 13.6-kb HindIII fragment from pXG914 cloned into pBR325; Apr, Cmr | This study |

| pXK65 | 13.6-kb HindIII fragment of pXK67 cloned into pGB-2; Smr, Spcr | This study |

| pXK50 | 12.7-kb HindIII-PmeI fragment of pXK45 cloned into pGB-2; Smr, Spcr | This study |

| pXK46 | 12.4-kb HindIII fragment of pXK67 cloned into pUC18; Apr | This study |

| pXK47 | 11.0-kb XbaI-HindIII fragment of pXK46 cloned into pUC18; Apr | This study |

| pXK2.1 | 2.1-kb HindIII fragment of pXK67 cloned into pUC18; Apr | This study |

| pXK1.2 | 1.2-kb HindIII fragment of pXK67 cloned into pUC18; Apr | This study |

| pXK1.4 | 1.4-kb XbaI-HindIII fragment of pXK46 cloned into pUC18; Apr | This study |

Cosmids pHC79 and pCVD551 (kindly provided by Timothy McDaniel, Center for Vaccine Development, University of Maryland, Baltimore) were employed to clone segments of the 180-kb plasmid of S. sonnei 53GI. Plasmid vectors pBR325, pGB2, and pUC18 were used for subcloning.

Bacterial strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar (Difco). Plasmid-containing strains were selected in medium containing ampicillin (Ap; 100 μg/ml), spectinomycin (Sp; 50 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (Cm; 35 μg/ml), or tetracycline (Tc; 20 μg/ml).

Plasmid manipulations.

Unless otherwise noted all DNA manipulations were performed essentially by following the procedures outlined by Sambrook et al. (35). Restriction enzymes were used with the buffers supplied by the manufacturer (Roche). Electroporation of plasmid constructs was performed with a Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad).

Cloning of S. sonnei form I genes.

pWR101 and pWR102 are form I antigen-expressing cosmids that contain large overlapping regions of the S. sonnei 180-kb plasmid from strain 53GI (D. J. Kopecko, L. S. Baron, T. L. Hale, S. B. Formal, and K. Noon, Abstr. 83rd Annu. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. D-10, 1983). These recombinant cosmids, initially selected in E. coli recipients on antibiotic-containing media, were identified by colony immunoblotting and bacterial agglutination assays by using purified form I O-antigen-specific, rabbit polyclonal antiserum (see below). The essential form I genes and flanking sequences were subcloned from the 39-kb insert of pWR101 (Table 1). First, pWR101 DNA was digested with BamHI and a resulting 30 kb fragment was ligated to the isoschizomer BglII-digested cosmid pCVD551. DNA was packaged in lambda phage particles in vitro by using a commercial kit (Gigapack II plus; Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Lambda-packaged DNA was used to infect E. coli HB101 or DH5α, and the recombinants were screened for form I antigen expression by colony immunoblotting. A HindIII partial digest of one form I-expressing clone, designated pXG914, was ligated to the multicopy plasmids pUC18 and pBR325 and the low-copy plasmid pGB-2 (7). Inserts representing one or more of three contiguous HindIII fragments of 12.4, 1.2, and 2.1 kb were initially obtained (i.e., pXK67, pXK68, pXK66, pXK65, and pXK46). Additional deletion derivatives (i.e., pXK45, pXK50, and pXK47) of this region were obtained to delimit the form I biosynthetic region (Table 1).

DNA sequencing and analysis.

DNA sequencing was performed with Ready Reactions DyeDeoxy Terminator cycle sequencing kits (Applied Biosystems) and an ABI model 373A automated sequencer. Subclones used for sequencing studies included pXK2.1, pXK1.2, pXK1.4, pXK47, and pXG914 (Table 1). Limited sequencing of pWR102 was also performed. Sequences were assembled and analyzed by using the Vector NTI suite 6.0 software (InforMax, Inc.). DNA homology searches were performed by using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) of the National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Antisera and bacterial agglutination.

Rabbit polyclonal form I-specific antiserum, kindly provided by S. Formal (Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Washington, D.C.), was produced by repeated immunization of New Zealand White rabbits with whole cells of heat-killed S. sonnei 53GI. Group D-specific Shigella typing serum (Difco) was also utilized. These rabbit antisera were absorbed with heat-treated (70°C, 30 min) S. sonnei form II and E. coli HB101 cells. Packed cells (0.1 ml) were added to 1.0 ml of undiluted or 10-fold-diluted antiserum, mixed, and incubated for 2 h at 37°C and overnight at 4°C. Following centrifugation, the absorbed antiserum was stored at 4°C for use in bacterial agglutination assays performed on microscope slides as previously described (12). Absorbed form I-specific antiserum did not agglutinate E. coli, S. sonnei 53GII, or Salmonella host strains.

LPS and immunoblot analyses.

Salmonella, Shigella, and E. coli strains carrying various plasmid constructs were grown overnight with aeration at 37°C in LB media containing appropriate antibiotics. Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation and were lysed in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer containing 4% 2-mercaptoethanol. The sample was boiled for 5 min, treated with proteinase K for 1 h, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE with a 15% gel and the Laemmli buffer system (28). Gels were silver-stained (22) or subjected to Western blotting with form I-specific antiserum.

Western blotting was performed by using polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Schleicher & Schuell). The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) and were reacted with anti-form I serum followed by protein A-alkaline phosphatase conjugate. The developing solution consisted of 200 mg of Fast Red TR salt and 100 mg of Naphthol NS-MX phosphate (Sigma) in 50 ml of 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.0).

Recombinant clones expressing the S. sonnei O-Ps were identified by colony immunoblotting performed with anti-form I serum and protein A-alkaline phosphatase conjugate as described above. Colonies of recipient E. coli, S. sonnei 53GII, or S. enterica serovar Typhi strains alone did not react with the absorbed form I-specific antisera under these conditions.

Stability of form I Ps expression in Salmonella strains.

Several S. enterica serovar Typhi Ty21a strains, each containing a different form I-expressing recombinant plasmid, were tested for stability of form I O-Ps expression. Each form I-expressing strain was diluted to approximately 100 CFU per ml and grown for 12 h (approximately 25 generations) with aeration at 37°C in LB media under nonselective conditions (i.e., without antibiotics). These cultures were diluted again to 100 CFU per ml in LB and were grown for an additional 12 h. Samples taken after 12 and 24 h of nonselective growth were plated onto LB agar without antibiotics and were incubated at 37°C. At least 100 colonies of each strain were tested at each time point for O-Ps expression by colony immunoblotting.

Animal immunization study.

Outbred ICR mice weighing from 13 to 15 g were used to assess immune protection as described previously (12). Vaccine candidate strains and control Ty21a alone were grown overnight in brain heart infusion broth (Difco) supplemented with 0.01% galactose, washed, and suspended in sterile saline to a concentration of 5 × 107 CFU per ml. Mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with a single 0.5-ml dose of either vaccine or control cell suspensions or sterile saline. Immunized and control mice were challenged intraperitoneally 5 weeks postimmunization with 5 × 105 CFU (approximately 100 times the 50% lethal infectious dose [LD50]) of freshly grown, mid-log-phase S. sonnei strain 53GI in 0.5 ml of 5% hog gastric mucin (Sigma) in sterile saline. Survival was monitored for 96 h.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers. The GenBank sequence accession number for the 17,986-bp sequence of pWR101 identified in this work is AF294823, and the accession number for the 2,964-bp sequence of pWR102 is AF455358.

RESULTS

Cloning and genetic downsizing for expression of the form I O-antigen locus.

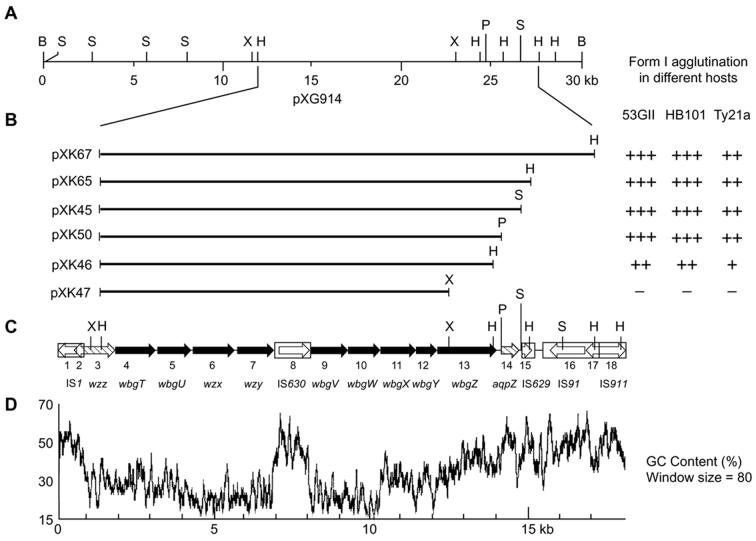

To delimit the DNA region required for biosynthesis of form I antigen, we initially cloned this region from S. sonnei strain 53GI in cosmids (see Materials and Methods). The 30-kb BamHI insert of pXG914, which directs the expression of typical form I LPS in E. coli, was partially digested with HindIII and separately ligated to low- and high-copy plasmid vectors pGB-2, pBR325, and pUC18. The resulting form I-expressing subclones (Table 1), containing inserts comprised of one or more of three adjacent HindIII fragments of 12.4, 1.2, and 2.1 kb (pXK67, pXK65, and pXK46, respectively) and several additional deletion derivatives (pXK45, pXK47, and pXK50), were characterized for form I expression in three host backgrounds (E. coli, S. enterica serovar Typhi, and S. sonnei) (Fig. 1). Plasmid inserts ranging in size from 15.7 to 12.4 kb all directed form I antigen expression in each host as shown by results of bacterial agglutination of plasmid-bearing subclones with form I-specific antiserum (Fig. 1B). However, this antiserum did not agglutinate bacteria containing pXK47, which contains an 11-kb insert, like the one previously reported (24) to contain the entire form I biosynthetic region. In the present study, the smallest inserts that directed form I antigen expression were the 12.7- and 12.4-kb inserts of plasmids pXK50 and pXK46, respectively. However, form I-specific agglutination of host strains containing pXK46 was weak and did not correlate with the detection of typical polymerized O antigen as described below.

FIG. 1.

Cloning and downsizing of the S. sonnei form I biosynthetic gene cluster for sequencing and O-antigen expression studies. (A) Restriction map of the 30-kb BamHI insert from cosmid pXG914. (B) The inserts of plasmid subclones prepared to define a minimal essential region for form I O-antigen expression, defined by anti-form I-specific bacterial agglutination of recipient S. sonnei 53GII, E. coli HB101, or S. enterica serovar Typhi Ty21a carrying each of these plasmids. (C) Map of the form I gene region showing restriction sites relative to inserts shown in panel B and the location of 18 ORFs identified by sequence analysis. Filled ORFs represent the genes required for form I Ps biosynthesis in plasmid-bearing subclones. Restriction endonuclease sites are shown for BamHI (B), HindIII (H), PmeI (P), SmaI (S), and XbaI (X). (D) Percent G+C content of the 17,986-bp form I biosynthetic region and flanking sequences.

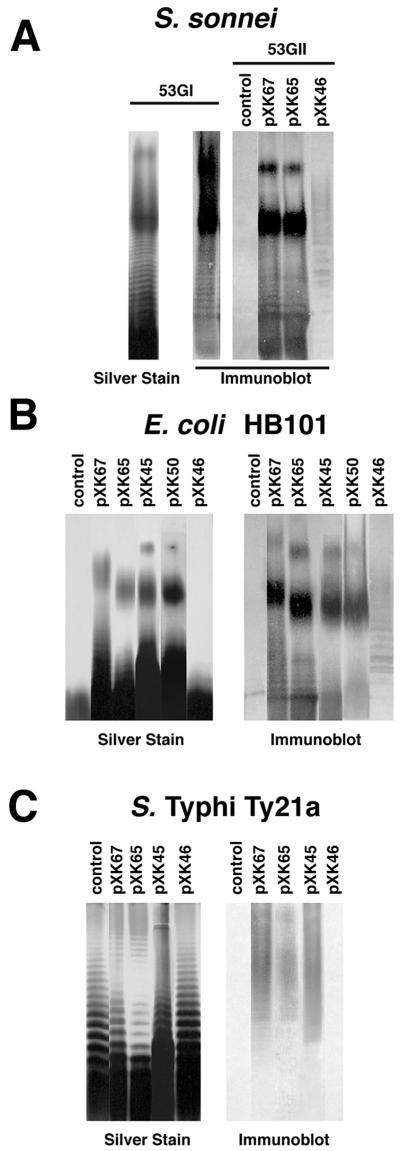

Plasmid-based expression of form I Ps in each host was further examined by SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining and Western blotting with form I-specific antisera (Fig. 2). LPS from wild-type S. sonnei 53GI gave a typical O-antigen ladder pattern with the predominant chain length of 20 to 25 O units as detected by silver stain or immunoblotting (Fig. 2A). Immunoblotting also detected additional material of lower mobility, well above the position of 25 O repeats, suggesting capsule-like expression. As expected, anti-form I reactive material was not detected with S. sonnei 53GII or rough E. coli HB101. However, recipient 53GII or HB101 carrying either pXK67 or pXK65 showed typical LPS ladder patterns like that seen from parent strain 53GI. Similar LPS ladder patterns were detected in further studies of E. coli carrying cosmid pWR101, pXG914, or pXK45, containing a 13.3-kb insert (Fig. 2B), or pXK50, containing a 12.7-kb insert (Fig. 2B). In contrast, a loss of form I immunoreactive material was noted for either Shigella (Fig. 2A) or E. coli (Fig. 2B) containing pXK46, which has a 12.4-kb insert. Moreover, host strains carrying pXK47, which has an 11-kb insert, showed no reaction by silver staining or immunoblotting (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Detection of SDS-PAGE-separated O-Ps by silver staining and anti-form I Western immunoblotting with form I-specific antiserum. O-Ps is from S. sonnei 53GI or strain 53GII alone (control) or carrying plasmids with different form I-encoding inserts (A); E. coli HB101 alone (control) or carrying different form I-encoding plasmids (B); and S. enterica serovar Typhi Ty21a alone (control) or carrying different form I-encoding plasmids (C).

S. enterica serovar Typhi Ty21a exhibited a typical and distinctive 9,12 LPS ladder pattern by silver stain analysis, but as expected it showed no form I antigen by immunoblotting (Fig. 2C). The presence of pXK67, pXK65, or pXK45 (Fig. 2C) or the smaller pXK50 (data not shown) in Ty21a did not noticeably affect the silver-stained O-antigen pattern of this strain. However, immunoblot analysis revealed that these plasmids directed the expression of form I immunoreactive material. The form I material in S. enterica serovar Typhi did not migrate as LPS and presumably was attached to carrier lipid as previously proposed (37). No immunoreactive form I Ps was detected in strain Ty21a carrying pXK46. Thus, the combined results suggest that plasmids pXK67, pXK65, pXK45, and pXK50 but not pXK46 contain the essential genes for synthesizing form I Ps in each of the three host strains examined.

Sequence analysis of the form I gene region.

A contiguous segment of about 18 kb was sequenced to characterize the form I biosynthetic gene region and evolutionarily important adjacent regions (see Fig. 1C; GenBank no. AF294823). Primary analysis of this sequence revealed 18 open reading frames (ORFs), the properties of which are summarized in Table 2 and Fig. 1. The notably higher G+C content for ORF8, ORF11 through ORF13, and other terminal sequences compared to that of the remainder of the form I region suggests different evolutionary origins for these sequences (Fig. 1D).

TABLE 2.

Summary of S. sonnei 53G ORFs

| ORF | Gene name | Location in sequence | % G+C | Amino acid no. | Selected homolog (accession no.) | % Identity (amino acids)a | Proposed function of 53G protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | insB | 519-16 | 54.4 | 167 | IS1 (InsB), E. coli (AJ223474) | 98 (167) | IS1 transposase |

| 2 | insA | 713-438 | 52.5 | 91 | IS1 (InsA), E. coli (AJ223475) | 100 (91) | IS1 protein |

| 3 | wzz | 788-1,720 | 36.4 | 310 | Wzz, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans (AB041266) | 35 (328) | Chain length determinant |

| Wzz, E. coli (AF011911) | 26 (292) | ||||||

| 4 | wbgT | 1,756-3,069 | 36.1 | 437 | WbpO, P. aeruginosa (AF035937) | 74 (418) | UDP-GalNAc dehydrogenase |

| WcdA, Salmonella typhi (D14156) | 63 (418) | ||||||

| 5 | wbgU | 3,150-4,187 | 34.1 | 345 | WbpP, P. aeruginosa (AF035937) | 67 (343) | UDP-GlcNAc C4 epimerase |

| WcdB, S. typhi (D14156) | 65 (338) | ||||||

| 6 | wzx | 4,276-5,556 | 28.1 | 426 | Cps19CJ, Streptococcus pneumoniae (AF105116) | 21 (394) | Repeat unit transporter |

| Wzx, E. coli (AF104912) | 19 (393) | ||||||

| 7 | wzy | 5,625-6,797 | 29.8 | 390 | Cap14H, S. pneumoniae (X85787) | 25 (201) | Polysaccharide polymerase |

| 8 | IS630 | 6,894-7,925 | 52.8 | 343 | IS630 (ORF343), S. sonnei (P16943) | 99 (343) | IS630 transposase |

| 9 | wbgV | 7,958-9,202 | 29.9 | 414 | None | None | UDP-GalNAcA C5 epimeraseb |

| 10 | wbgW | 9,186-10,181 | 26.6 | 331 | WaaV, E. coli (AF019746) | 27 (237) | Glycosyl transferase |

| LgtA, N. gonorrhoeae (U14554) | 30 (142) | ||||||

| 11 | wbgX | 10,178-11,332 | 37.6 | 384 | WlbF, Bordetella bronchiseptica (AJ007747) | 55 (392) | Amino-sugar synthetase |

| Per, E. coli (AF061251) | 34 (383) | ||||||

| RfbE, V. cholerae (X59554) | 31 (380) | ||||||

| 12 | wbgY | 11,349-11,939 | 35.4 | 196 | WlbG, Bordetella pertussis (X90711) | 53 (194) | Glycosyl transferase |

| WcaJ, E. coli K-12 (U38473) | 34 (197) | ||||||

| WbaP, E. coli K30 (AF104912) | 31 (212) | ||||||

| 13 | wbgZ | 11,954-13,873 | 44.3 | 639 | WbcP, Yersinia enterocolitica (Z47767) | 68 (633) | UDP-GlcNAc C6 dehydratase C4 reductase |

| WbpM, P. aeruginosa (U50396) | 49 (657) | ||||||

| WlbL, B. pertussis (X90711) | 49 (592) | ||||||

| FlaA1, H. pylori (AE000595) | 28 (297) | ||||||

| 14 | aqpZ | 13,992-14,504 | 55.5 | 170 | ORF10P, P. shigelloides (AB025970) | 99 (146) | Water channel protein |

| AqpZ, E. coli (AE000189) | 71 (146) | ||||||

| 15 | orfA | 14,657-14,983 | 53.8 | 108 | IS629 (ORFA), S. sonnei (P16941) | 99 (108) | IS629 transposase |

| 16 | InsB | 16,706-15,486 | 55.0 | 406 | IS91 (TnpA), E. coli (X17114) | 94 (406) | IS91 transposase |

| 17 | InsA | 17,071-16,706 | 53.0 | 121 | IS91 (ORF121), E. coli (S23781) | 95 (121) | IS91 protein |

| 18 | InsB | 17,130-17,978 | 54.8 | 282 | IS911 (InsB), S. dysenteriae (AAF28127) | 99 (271) | IS911 transposase |

Percent identity and length of comparable sequence in the homologous protein obtained from BLAST analysis.

Proposed function based on the predicted presence of an enzyme that converts UDP-GalNAcA to UDP-AltNAcA (see Discussion).

The inserts of all plasmids that direct the expression of typical form I antigen (Fig. 1B) begin at the HindIII site located at nucleotide position 1,310 of our sequence, in the middle of ORF3, a homolog of wzz. Ten identically oriented ORFs (ORF4 to ORF13) occur within the 12.7-kb insert of pXK50, the smallest insert that directs typical form I antigen expression. One of these ORFs (ORF8 in Fig. 1C) represents the transposase of IS630, which is inserted nonpolarly into the C terminus of the preceding biosynthetic ORF as noted previously (38). All remaining ORFs present within the pXK50 insert are homologs of known genes for Ps biosynthesis (Table 2), except ORF9, which we suggest encodes a C5 epimerase (see Discussion). The presence of a putative promoter, identified by a −35 and −10 consensus sequence (ATTACCN15TATAGT) at nucleotide positions 1,645 to 1,671 of our sequence (AF294823), and a typical transcriptional terminator, which was identified by a stem-loop structure and an adjacent poly(T) sequence at nucleotide positions 13,930 to 13,949, define an essential 12.3-kb region required for form I Ps biosynthesis by our plasmid subclones. This region, which contains 10 intact ORFs, including the transposase of IS630, begins near the 3′ end of ORF3 and ends between ORF13 and ORF14 (Fig. 1C).

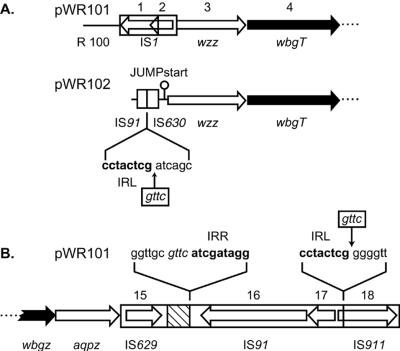

Sequencing of the regions adjacent to the form I O-Ps operon revealed several interesting features that aid in understanding the evolution of the plasmid-borne form I region. Analysis of upstream sequences from pWR101 subclones revealed the presence of a partial wzz (933 bp) created by an IS1 insertion. Sequence homology to the plasmid R100 was noted immediately 5′ of this IS1 element (D.-Q. Xu, J. Cisar, and D. Kopecko, unpublished data) (Fig. 3A). Unexpectedly, the 5′ region adjacent to the form I operon in pWR101 differed from that in pWR102. The latter plasmid contained a partial IS91 (201 bp), a partial IS630 (339 bp), a JUMPstart sequence(CAGCGCTTTGGGAGCTGAAACTCAAGGGCGGTAGCGTA) which is characteristic of O-antigen loci, and a full-length copy of wzz (1,104 bp) (Fig. 3A). The observation of a full-length S. sonnei plasmid-borne wzz, as reported previously (38), preceded by a JUMPstart sequence and partial IS elements, suggests that this pWR102-derived sequence represents that of the original 180-kb S. sonnei virulence plasmid and that during subcloning of this region in pWR101 an IS1 element insertion occurred within wzz, causing a 5′ deletion of this gene and adjacent upstream sequences (Fig. 1C and 3A). The remnants of IS630 and IS91 found upstream of JUMPstart in pWR102 suggests the insertion of IS91 via its left inverted repeat into a GTTC target site (33) originally present within IS630 and subsequent deletion of much of the IS91 element (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

ORF diagrams of the regions flanking the S. sonnei form I biosynthetic gene cluster. (A) Regions of pWR101 and pWR102 upstream of wbgT. (B) Region of pWR101 downstream of wbgZ. The sequences of the left and right inverted repeats (IRL and IRR) of IS91 are shown in bold type. The gttc target sequence of IS91 is italicized. The original gttc sites within IS630 and IS911 for insertion of IS91 are boxed. A sequence homologous to a Pseudomonas IS element (accession number Y17830) occurs within the 263-bp hatched region.

Immediately downstream of the form I-encoding region, a partial aqpZ gene (513 bp) was found that is virtually identical to the 5′ portion of Pleisiomonas shigelloides aqpZ (699 bp) (6). Further downstream a partial IS629 element (31), a small fragment of a Pseudomonas IS element, full-length IS91, and partial IS911 sequences were identified (Fig. 3B and 4A). The specific target sequence of IS91, GTTC, was found immediately adjacent to the right inverted repeat of this element, indicating the prior insertion of IS91 into a target site originally present in the middle of IS911. Thus, the region downstream of the form I biosynthetic operon contains numerous IS element remnants, and like the upstream region it serves as a recombinational hotspot.

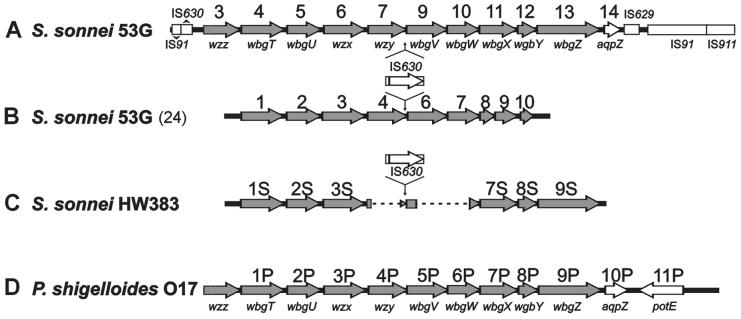

FIG. 4.

Comparison of gene clusters for biosynthesis of the S. sonnei form I Ps and P. shigelloides O17 Ps. (A) Composite S. sonnei 53G form I gene cluster and flanking regions derived from sequences AF285971, AF294823, and AF455358. ORFs are identified numerically as defined in Table 2 and also by gene designations (38). (B) S. sonnei 53G form I gene cluster reported by Houng and Venkatesan (24). (C) Partial S. sonnei HW383 form I gene cluster determined by Chida et al. (6). (D) Composite P. shigelloides O17 Ps gene cluster derived from sequences AF285970 and AB025970. ORFs are identified numerically and by gene names (38). The ORFs associated with form I Ps biosynthesis are shaded.

Stability of form I Ps expression in a Salmonella vaccine vector.

Several recombinant plasmids were tested for their ability to direct stable form I Ps expression in S. enterica serovar Typhi Ty21a. Following electroporation of each plasmid into strain Ty21a, the resulting strain was grown in the absence of antibiotic selective pressure for approximately 25 and 50 generations and then examined for form I antigen expression. The percentage of form I-positive colonies was determined by immunoblot assay of colonies grown on LB agar without antibiotic. Salmonella harboring the 15.7-kb form I region insert in the multicopy vector pBR325 (i.e., pXK68) exhibited highly unstable form I Ps expression. Thus, following growth for 24 h, the loss of antigen expression from Salmonella carrying this plasmid was greater than 97% (Table 3). Deletion of IS91 from the 15.7-kb insert of pXK68 to generate the 13.6-kb fragment of pXK66 increased the stability of form I Ps expression. The percentage of form I-positive colonies was further enhanced when these inserts were carried in the low-copy vector, pGB2. The 15.7-kb insert in pGB-2 (i.e., pXK67) exhibited markedly improved stability of antigen expression compared to that of the same insert in pBR325. Again, deletion of IS91 from the 15.7-kb insert of pXK67 to generate the 13.6-kb fragment of pXK65 increased the stability of form I Ps expression. In fact, as shown in Table 3, pXK65 and pXK45 directed stable form I antigen expression in Salmonella over 50 generations.

TABLE 3.

Stability of plasmid-based form I Ps expression in S. enterica serovar Typhi Ty21aa

| Plasmid | Vector | Insert size (kb) | % Form I Ps-positive colonies at:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 h | 24 h | |||

| pXK68 | pBR325 | 15.7 | 12.5 | 2.5 |

| pXK66 | pBR325 | 13.6 | 80 | 45.5 |

| pXK67 | pGB-2 | 15.7 | 78 | 69 |

| pXK65 | pGB-2 | 13.6 | 100 | 98.5 |

| pXK45 | pGB-2 | 13.3 | 100 | 97 |

A form I-positive colony of each strain was inoculated in LB broth and grown for 12 h (approximately 25 generations) before dilution and regrowth in fresh LB broth for an additional 12 h. Samples taken at 12 or 24 h were plated on LB agar, and the resulting colonies were assayed for form I Ps by colony immunoblotting.

Vaccine protection study with mice.

Shigellae are specific for higher primates, and nonprimate models do not exist for the development of either typical dysenteric disease from low infectious doses of these bacteria or protective immunity from natural challenge. Nevertheless, mice have been employed previously to demonstrate immune stimulation by a vaccine and specific protection against parenteral challenge with virulent S. sonnei (12). In the present study, ICR mice were immunized with a single intraperitoneal dose of viable S. enterica serovar Typhi Ty21a containing pXK65 or pXK45, Ty21a alone, or saline and were challenged at 5 weeks postimmunization with 5 × 105 virulent S. sonnei 53GI (i.e., approximately 100 × LD50). This challenge resulted in 100% mortality in negative control mice immunized with saline or strain Ty21a alone (Table 4). In contrast, all mice that received Ty21a harboring the stable form I inserts deleted for IS91 and carried by pGB-2 were protected from the S. sonnei challenge.

TABLE 4.

Mouse protection against virulent S. sonnei challenge

| Vaccine (plasmid) or controla | Survivors/totalb |

|---|---|

| S. enterica serovar Typhi Ty21a (pXK45) | 8/8 |

| S. enterica serovar Typhi Ty21a (pXK65) | 8/8 |

| S. enterica serovar Typhi Ty21a | 0/8 |

| Saline | 0/8 |

Vaccine strains containing plasmids or control Ty21a alone were suspended in saline to a concentration of 2.5 × 107 cells per 0.5-ml dose for intraperitoneal immunization. Saline (0.5 ml) served as a control.

Each mouse was challenged intraperitoneally with 5 × 105 CFU of S. sonnei 53GI (i.e., 100 × LD50) in 0.5 ml of saline containing 5% hog gastric mucin and was monitored for 4 days.

DISCUSSION

The genes controlling form I Ps biosynthesis have previously been cloned and sequenced to various extents, as summarized in Fig. 4 (D. J. Kopecko et al., Abstr. 83rd Annu. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. D-10, 1983, and references 6, 24, 38, 42, 45). However, reported sequence differences in the S. sonnei form I gene region (Fig. 4A and B), combined with limited analyses of LPS expression, have resulted in confusion regarding the essential genes for form I antigen biosynthesis. Houng and Venkatesan (24) reported that these genes were contained within an 11-kb region of the S. sonnei 53GI virulence plasmid; DNA sequencing revealed 10 ORFs, including IS630 (Fig. 4B). However, our findings, which support other recent sequencing studies of the form I gene region in S. sonnei strains 53GI and HW383 (Fig. 4A and C) as well as the corresponding gene region of P. shigelloides (Fig. 4D), suggest that the form I biosynthetic region contains an additional gene, designated wbgZ (Fig. 4A), homologs of which occur in many Ps gene clusters (5) but not in the sequence of Houng and Venkatesan (24) (Fig. 4B).

Antibody to form I Ps was previously reported to agglutinate subclones expressing an 11-kb form I insert (24), which lacks wbgZ. In contrast, we found that such subclones (i.e., pXK47) were not agglutinated by specific anti-form I antibody, prepared by absorption with form II S. sonnei cells. Further, LPS analysis by silver stain or immunoblot showed no detectable form I material from subclones expressing the 11-kb insert but did show typical form I LPS from pXK50 subclones expressing the 12.7-kb insert, thereby indicating that wbgZ (but not aqpZ) is required for form I Ps biosynthesis. The right-hand end of the form I gene region, between wbgZ and aqpZ, is further defined by the presence of a transcriptional terminator in this region and the dramatic effect on Ps synthesis seen from the short truncation of wbgZ in subclones expressing the 12.4-kb insert (Fig. 2, pXK46). E. coli or Shigella harboring pXK46 weakly expressed anti-form I immunoreactive material, which differed from typical O-Ps in silver stain and immunoblot patterns.

The left-hand end of the essential form I region is defined by plasmid inserts that begin in the middle of wzz (Fig. 1B) but direct the synthesis of typical form I LPS. The wild-type distribution of LPS chain length seen in our S. sonnei subclones (Fig. 2A) can be explained by the expression of the previously described chromosomal wzz (38), which apparently determines the chain length of form I LPS. Whereas JUMPstart, a presumed transcriptional antiterminator (43), and plasmid-borne wzz may play a role in biosynthesis of LPS by wild-type S. sonnei and P. shigelloides 017, our studies indicate that neither of these loci is essential for form I Ps expression from our subclones. Such observations also suggest the presence of a promoter at the 3′ end of plasmid-borne wzz (6) immediately ahead of wbgT, the first essential gene for plasmid-based form I Ps biosynthesis. The IS630 element inserted in the C terminus of ORF7 (i.e., wzy) (38) is evidently also not essential for form I Ps biosynthesis, as the comparable region of P. shigelloides, which lacks IS630, also directs the production of typical LPS. Thus, the available data from studies of LPS biosynthesis clearly indicate that nine genes beginning with wbgT (ORF4) and ending with wbgZ (ORF13) (Fig. 4A) are required for form I antigen biosynthesis in each of the three host genera examined.

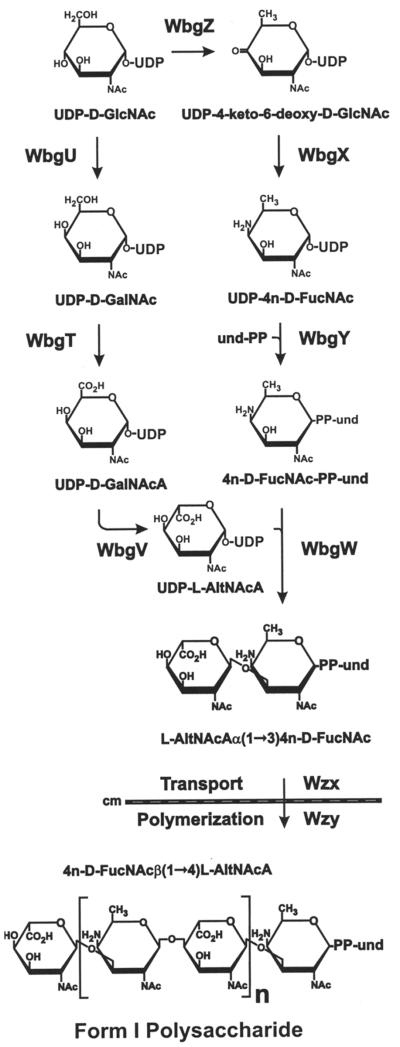

The properties of these nine essential genes (Table 2) provide the basis for the detailed biosynthetic pathway presented as a working hypothesis in Fig. 5. These genes include two (wbgW and wbgY) for putative glycosyl transferases and two (wzx and wzy) for proteins that function in the transport and polymerization of form I repeating units. Thus, the remaining five genes of the form I cluster may function to convert available nucleotide-linked sugars to the 4-n-d-FucNAc- and l-AltNAcA-containing precursors of the form I disaccharide repeating unit (25). The initial step in formation of UDP-4-n-d-FucNAc was previously proposed to involve conversion of UDP-GlcNAc to UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-GlcNAc by the action of WbgV (38). We suspect that WbgZ, rather than WbgV, catalyzes this reaction. Homologs of WbgZ, which include FlaA1 of Helicobacter pylori and WbpM of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, are associated with synthesis of the 2,6-deoxysugars QuiNAc and d-FucNAc and structurally related derivatives, such as 4-n-d-QuiNAc (5), the C4 epimer of 4-n-d-FucNAc. Significantly, FlaA1 of H. pylori has recently been identified as a bifunctional UDP-GlcNAc C6 dehydratase/C4 reductase that catalyzes the conversion of UDP-GlcNAc to UDP-QuiNAc through a stable intermediate, UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-GlcNAc (8). Consequently, the predicted intermediate product of WbgZ, UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-GlcNAc, is the putative substrate of WbgX (38), which likely catalyzes the formation of 4-n-d-FucNAc (Fig. 5) in a manner similar to the conversion of GDP-4-keto-6-deoxymannose to GDP-perosamine by perosamine synthase of Vibrio cholerae O1 (39) and E. coli (2).

FIG. 5.

Proposed pathway for biosynthesis of undecaprenyl phosphate (und-P)-linked, S. sonnei form I Ps. The pathway is based on the predicted enzymatic activities of S. sonnei 53G proteins as summarized in Table 2 and the structural steps required for conversion of UDP-GlcNAc to the putative form I Ps precursors, UDP-l-AltNAcA and UDP-4n-d-FucNAc.

Homologs of two other S. sonnei biosynthetic genes, wbgT and wbgU, occur in a number of bacteria that synthesize N-acetylgalactosamine uronic acid (GalNAcA), including P. aeruginosa serotype 06 (1) and Vi-capsule-expressing Salmonella serovars (19) (Table 2). The relevant biosynthetic pathway, proposed from studies of P. aeruginosa (1), involves the conversion of UDP-GlcNAc to UDP-GalNAc by WbpO and subsequent conversion of UDP-GalNAc to UDP-N-GalNAcA by WbpP. Indeed, recent biochemical studies confirm the identification of WbpP as a UDP-GlcNAc C4 epimerase (8) and WbpO as a UDP-GalNAc dehydrogenase (46). Significantly, d-GalNAcA, the predicted product of WbgT in S. sonnei, is the C5 epimer of l-AltNAcA, a constituent of form I Ps. Thus, the corresponding precursor, UDP-l-AltNAcA, would be obtained by the action of a C5 epimerase on UDP-GalNAcA. We predict that this activity is provided by WbgV (Fig. 5), the only S. sonnei ORF that failed to retrieve significant homologs from the database (Table 2). Although weak homology between WbgV and plant NADH dehydrogenases was previously reported (38), we found that WbgV is not affiliated with these or other NADH-containing enzymes in the Blocks Data Base (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center), thereby calling into question the identification of WbgV as a dehydrogenase. Intracellular C5 epimerases that act on nucleotide-linked sugars have not been described to our knowledge, which may contribute to the apparent absence of WbgV homologs in the database. Extracellular C5 epimerases that act on polysaccharides are, however, well documented and include the enzymes of P. aeruginosa (13) and Azotobacter vinelandii (11) that convert d-mannuronic acid to l-glucuronic acid in alginate polymers as well as mammalian enzymes that convert d-glucuronic acid to l-iduronic acid in heparin and heparin sulfate (30).

That the form I Ps is linked to the phase II core of S. sonnei (25) through 4-n-d-FucNAc suggests that 4-n-d-FucNAc is the first sugar attached to the acyl carrier lipid. This step almost certainly depends on WbgY, which is a homolog of several well-studied glycosyl transferases that link the first sugar of different O-antigen repeating units to carrier lipid (Table 2). WbgW, the other predicted glycosyl transferase (Table 2), presumably completes the biosynthetic unit by transferring l-AltNAcA, thereby forming l-AltNAcAα(1→3)4-n-D-FucNAc-PP-und. Indeed, the predicted α(1→3) transfer of l-AltNAcAα by WbgW would resemble the known β(1→3) transfer of d-sugars by WaaV (20) of E. coli and LgtA of Neisseria gonorrhoeae (16) (Table 2). On the basis of its predicted size (Table 2) and hydropathy profile (results not shown), Wzx, a member of the PST(2) subfamily of polysaccharide transport proteins (34), would then be expected to flip the lipid-linked repeating unit from the cytoplasmic to periplasmic face of the plasma membrane without the aid of auxiliary export proteins. Wzx-mediated transport would provide the substrate for Wzy-dependent polymerization, resulting in the formation of a β1-4 linkage between each adjacent repeating unit, thereby completing the form I Ps structure (Fig. 5).

Plasmid-based expression of form I Ps in S. enterica serovar Typhi Ty21a, which has a core that is chemically dissimilar to that of shigellae, resulted in the production of a lipid-linked surface Ps (37) rather than typical form I LPS (Fig. 2C). In contrast, a significant fraction of form I Ps synthesized in S. sonnei and E. coli was ligated to core lipid A. However, even from these species a slow migrating band of form I immunoreactive material, apparently not linked to core lipid A, was detected (Fig. 2A and B). It is unclear whether this band of non-core-linked form I material is surface associated through the acyl carrier lipid or, alternatively, through another molecule as an O-antigen capsule. As pointed out in a recent review (44), O-Ps capsules are easily overlooked because serological and structural studies have generally been interpreted with the expectation that all surface O antigen is core-lipid-A-linked. However, examples such as E. coli serotype O111 have long been recognized (15) in which the same O-Ps is surface expressed in a LPS form and in a non-LPS-linked capsular form. Clearly, further studies of S. sonnei form I Ps are needed to clarify this possibility.

High homology between the gene regions for O-Ps biosynthesis in S. sonnei and P. shigelloides (6, 38) over the region from wzz to aqpZ (Fig. 4) supports the proposal of Lai and coworkers (29) that S. sonnei evolved from E. coli by the acquisition of the form I biosynthetic region from P. shigelloides. The form I operon adjacent sequences obtained herein (Fig. 1C and 3) provide an improved definition of the limits of the gene transfer event. Comparison of the available S. sonnei form I gene region sequences (Fig. 4A) with the analogous Pleisiomonas region (Fig. 4D) suggests the transfer of approximately 12.6 kb of P. shigelloides chromosomal DNA. The right-hand endpoint apparently occurred at bp 513 within aqpZ, where sequence homology between P. shigelloides and S. sonnei ends abruptly. The left-hand junction apparently occurred upstream of JUMPstart, where partial IS elements were identified in pWR102 (Fig. 3). Since remnants of IS91, IS630, and other elements have been shown to flank the form I operon in S. sonnei (Fig. 3 and 4A), any of these elements could have been involved in transposition of this region, likely from the Pleisiomonas chromosome to a plasmid, which was then transferred to the evolving E. coli recipient.

Form I antigen expression is frequently lost in S. sonnei mainly by spontaneous loss of the large virulence plasmid (26). Instead of stabilizing form I expression in attenuated Shigella for use as a live vaccine, our approach has been to transfer the form I genes into S. enterica serovar Typhi Ty21a. Ty21a (14) is a proven safe and effective, mucosally delivered, live bacterial vaccine which stimulates long-term protection against typhoid fever. In addition, Ty21a has the advantage of oral administration, eliminating the need for needles, syringes, and a skilled health professional for immunization. A live, oral candidate vaccine strain, 5076-1C, was previously constructed by introducing the large S. sonnei virulence plasmid into Ty21a. The resulting strain was protective in humans challenged with virulent S. sonnei (3, 12, 21) but was genetically unstable, resulting in loss of form I O-Ps expression (17). The present study has allowed us to create stable, minimum-sized S. sonnei form I region constructs in Ty21a. The stability of plasmid-based expression of form I O-Ps was enhanced by deletion of the downstream IS91 from form I inserts and was further stabilized by use of the low-copy vector pGB-2 (Table 3). Animal studies (Table 4) have provided preclinical evidence that these minimum-sized form I region constructs in S. enterica serovar Typhi induced protective immunity in a stringent mouse challenge model. We believe that these live-vectored candidates have great potential for use as oral vaccines for human protection against shigellosis due to S. sonnei.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge K. Noon for expert technical assistance in initial cosmid cloning of the form I biosynthetic region, and we thank C. Frasch, M. Schmitt, and W. Vann for their constructive comments and critical review of the manuscript.

Editor: J. D. Clements

REFERENCES

- 1.Belanger, M., L. L. Burrows, and J. S. Lam. 1999. Functional analysis of genes responsible for the synthesis of the B-band O antigen of Pseudomonas aeruginosa serotype O6 lipopolysaccharide. Microbiology 145:3505-3521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bilge, S. S., J. C. Vary, Jr., S. F. Dowell, and P. I. Tarr. 1996. Role of the Escherichia coli O157:H7 O side chain in adherence and analysis of an rfb locus. Infect. Immun. 64:4795-4801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black, R. E., M. M. Levine, M. L. Clements, G. Losonsky, D. Herrington, S. Berman, and S. B. Formal. 1987. Prevention of shigellosis by a Salmonella typhi-Shigella sonnei bivalent vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 155:1260-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolivar, F. 1978. Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. III. Derivatives of plasmid pBR322 carrying unique Eco RI sites for selection of Eco RI generated recombinant DNA molecules. Gene 4:121-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burrows, L. L., R. V. Urbanic, and J. S. Lam. 2000. Functional conservation of the polysaccharide biosynthetic protein WbpM and its homologues in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other medically significant bacteria. Infect. Immun. 68:931-936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chida, T., N. Okamura, K. Ohtani, Y. Yoshida, E. Arakawa, and H. Watanabe. 2000. The complete DNA sequence of the O antigen gene region of Plesiomonas shigelloides serotype O17 which is identical to Shigella sonnei form I antigen. Microbiol. Immunol. 44:161-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Churchward, G., D. Belin, and Y. Nagamine. 1984. A pSC101-derived plasmid which shows no sequence homology to other commonly used cloning vectors. Gene 31:165-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Creuzenet, C., M. Schurr, J. Li, W. W. Wakarchuk, and J. S. Lam. 2000. FlaA1, a new bifunctional UDP-GlcNAc C6 dehydratase/C4 reductase from Helicobacter pylori. J. Biol. Chem. 275:34873-34880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DuPont, H. L., R. B. Hornick, M. J. Snyder, J. P. Libonati, S. B. Formal, and E. J. Gangarosa. 1972. Immunity in shigellosis. I. Response of man to attenuated strains of Shigella. J. Infect. Dis. 125:5-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DuPont, H. L., R. B. Hornick, M. J. Snyder, J. P. Libonati, S. B. Formal, and E. J. Gangarosa. 1972. Immunity in shigellosis. II. Protection induced by oral live vaccine or primary infection. J. Infect. Dis. 125:12-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ertesvag, H., B. Doseth, B. Larsen, G. Skjak-Braek, and S. Valla. 1994. Cloning and expression of an Azotobacter vinelandii mannuronan C-5- epimerase gene. J. Bacteriol. 176:2846-2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Formal, S. B., L. S. Baron, D. J. Kopecko, O. Washington, C. Powell, and C. A. Life. 1981. Construction of a potential bivalent vaccine strain: introduction of Shigella sonnei form I antigen genes into the galE Salmonella typhi Ty21a typhoid vaccine strain. Infect. Immun. 34:746-750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franklin, M. J., C. E. Chitnis, P. Gacesa, A. Sonesson, D. C. White, and D. E. Ohman. 1994. Pseudomonas aeruginosa AlgG is a polymer level alginate C5-mannuronan epimerase. J. Bacteriol. 176:1821-1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Germanier, R., and E. Furer. 1975. Isolation and characterization of Gal E mutant Ty21a of Salmonella typhi: a candidate strain for a live, oral typhoid vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 131:553-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldman, R. C., D. White, F. Orskov, I. Orskov, P. D. Rick, M. S. Lewis, A. K. Bhattacharjee, and L. Leive. 1982. A surface polysaccharide of Escherichia coli O111 contains O antigen and inhibits agglutination of cells by O antiserum. J. Bacteriol. 151:1210-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gotschlich, E. C. 1994. Genetic locus for the biosynthesis of the variable portion of Neisseria gonorrhoeae lipooligosaccharide. J. Exp Med. 180:2181-2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartman, A. B., M. M. Ruiz, and C. L. Schultz. 1991. Molecular analysis of variant plasmid forms of a bivalent Salmonella typhi-Shigella sonnei vaccine strain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:27-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartman, A. B., and M. M. Venkatesan. 1998. Construction of a stable attenuated Shigella sonnei ΔvirG vaccine strain, WRSS1, and protective efficacy and immunogenicity in the guinea pig keratoconjunctivitis model. Infect. Immun. 66:4572-4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashimoto, Y., N. Li, H. Yokoyama, and T. Ezaki. 1993. Complete nucleotide sequence and molecular characterization of ViaB region encoding Vi antigen in Salmonella typhi. J. Bacteriol. 175:4456-4465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinrichs, D. E., M. A. Monteiro, M. B. Perry, and C. Whitfield. 1998. The assembly system for the lipopolysaccharide R2 core-type of Escherichia coli is a hybrid of those found in Escherichia coli K-12 and Salmonella enterica. Structure and function of the R2 WaaK and WaaL homologs. J. Biol. Chem. 273:8849-8859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herrington, D. A., L. Van de Verg, S. B. Formal, T. L. Hale, B. D. Tall, S. J. Cryz, E. C. Tramont, and M. M. Levine. 1990. Studies in volunteers to evaluate candidate Shigella vaccines: further experience with a bivalent Salmonella typhi-Shigella sonnei vaccine and protection conferred by previous Shigella sonnei disease. Vaccine 8:353-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hitchcock, P. J., and T. M. Brown. 1983. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J. Bacteriol. 154:269-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hohn, B., and J. Collins. 1980. A small cosmid for efficient cloning of large DNA fragments. Gene 11:291-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Houng, H. S., and M. M. Venkatesan. 1998. Genetic analysis of Shigella sonnei form I antigen: identification of a novel IS630 as an essential element for the form I antigen expression. Microb. Pathog. 25:165-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kenne, L., B. Lindberg, K. Petersson, E. Katzenellenbogen, and E. Romanowska. 1980. Structural studies of the O-specific side-chains of the Shigella sonnei phase I lipopolysaccharide. Carbohydr. Res. 78:119-126. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kopecko, D. J., O. Washington, and S. B. Formal. 1980. Genetic and physical evidence for plasmid control of Shigella sonnei form I cell surface antigen. Infect. Immun. 29:207-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kotloff, K. L., J. P. Winickoff, B. Ivanoff, J. D. Clemens, D. L. Swerdlow, P. J. Sansonetti, G. K. Adak, and M. M. Levine. 1999. Global burden of Shigella infections: implications for vaccine development and implementation of control strategies. Bull. W. H. O. 77:651-666. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai, V., L. Wang, and P. R. Reeves. 1998. Escherichia coli clone Sonnei (Shigella sonnei) had a chromosomal O-antigen gene cluster prior to gaining its current plasmid-borne O-antigen genes. J. Bacteriol. 180:2983-2986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, J., A. Hagner-McWhirter, L. Kjellen, J. Palgi, M. Jalkanen, and U. Lindahl. 1997. Biosynthesis of heparin/heparan sulfate. cDNA cloning and expression of D-glucuronyl C5-epimerase from bovine lung. J. Biol. Chem. 272:28158-28163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsutani, S., and E. Ohtsubo. 1990. Complete sequence of IS629. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mead, P. S., L. Slutsker, V. Dietz, L. F. McCaig, J. S. Bresee, C. Shapiro, P. M. Griffin, and R. V. Tauxe. 1999. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5:607-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mendiola, M. V., Y. Jubete, and F. de la Cruz. 1992. DNA sequence of IS91 and identification of the transposase gene. J. Bacteriol. 174:1345-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paulsen, I. T., J. H. Park, P. S. Choi, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1997. A family of gram-negative bacterial outer membrane factors that function in the export of proteins, carbohydrates, drugs and heavy metals from gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 156:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 36.Sansonetti, P. J., D. J. Kopecko, and S. B. Formal. 1981. Shigella sonnei plasmids: evidence that a large plasmid is necessary for virulence. Infect. Immun. 34:75-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seid, R. C., Jr., D. J. Kopecko, J. C. Sadoff, H. Schneider, L. S. Baron, and S. B. Formal. 1984. Unusual lipopolysaccharide antigens of a Salmonella typhi oral vaccine strain expressing the Shigella sonnei form I antigen. J. Biol. Chem. 259:9028-9034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shepherd, J. G., L. Wang, and P. R. Reeves. 2000. Comparison of O-antigen gene clusters of Escherichia coli (Shigella) Sonnei and Plesiomonas shigelloides O17: Sonnei gained its current plasmid-borne O-antigen genes from P. shigelloides in a recent event. Infect. Immun. 68:6056-6061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stroeher, U. H., L. E. Karageorgos, M. H. Brown, R. Morona, and P. A. Manning. 1995. A putative pathway for perosamine biosynthesis is the first function encoded within the rfb region of Vibrio cholerae O1. Gene 166:33-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van de Verg, L., D. A. Herrington, J. R. Murphy, S. S. Wasserman, S. B. Formal, and M. M. Levine. 1990. Specific immunoglobulin A-secreting cells in peripheral blood of humans following oral immunization with a bivalent Salmonella typhi-Shigella sonnei vaccine or infection by pathogenic S. sonnei. Infect. Immun. 58:2002-2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vieira, J., and J. Messing. 1982. The pUC plasmids, an M13mp7-derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene 19:259-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Viret, J. F., S. J. Cryz, Jr., A. B. Lang, and D. Favre. 1993. Molecular cloning and characterization of the genetic determinants that express the complete Shigella serotype D (Shigella sonnei) lipopolysaccharide in heterologous live attenuated vaccine strains. Mol. Microbiol. 7:239-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang, L., S. Jensen, R. Hallman, and P. R. Reeves. 1998. Expression of the O antigen gene cluster is regulated by RfaH through the JUMPstart sequence. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 165:201-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whitfield, C., and I. S. Roberts. 1999. Structure, assembly and regulation of expression of capsules in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1307-1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshida, Y., N. Okamura, J. Kato, and H. Watanabe. 1991. Molecular cloning and characterization of form I antigen genes of Shigella sonnei. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:867-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao, X., C. Creuzenet, M. Belanger, E. Egbosimba, J. Li, and J. S. Lam. 2000. WbpO, a UDP-N-acetyl-D-galactosamine dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa serotype O6. J. Biol. Chem. 275:33252-33259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]