Abstract

Increasing the growth temperature from 28 to 37°C reduced the expression of β-1,2-oligomannoside epitopes on mannoproteins of Candida albicans serotypes A and B. In contrast, β-1,2-mannosylation of phospholipomannan (PLM) remained constant despite a slight decrease in the relative molecular weight (Mr) of this compound. At all growth temperatures investigated, serotype A PLM displayed an Mr and an antigenicity different from those of serotype B PLM when they were tested with a panel of monoclonal antibodies.

Genotypic or phenotypic regulation of surface antigens depends on adaptive pathways that are used by numerous pathogens to escape from host defenses. In Candida albicans, molecular rearrangement of cell wall molecules, dimorphism (17, 29), and phenotypic switching (34) are thought to help the yeast avoid the host response. Sequences of β-1,2-linked mannose residues are located at the C. albicans cell surface, and they act as adhesins (20, 25), induce protective antibodies (9, 15) and cytokines (19), and are thought to contribute to virulence. These biological activities have been demonstrated by using β-1,2-oligomannosides released from C. albicans cell wall mannan by mild acid hydrolysis. Structural analysis by nuclear magnetic resonance (30) and fluorophore-assisted carbohydrate electrophoresis (14, 26, 30) has demonstrated that the quantities and chain lengths of β-1,2-oligomannosides released from the mannan vary according to the growth conditions (namely, pH and temperature or hydrophobicity). In the serological classification of Tsuchiya et al. (41) used to develop the Iatron kit (Iatron Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan), β-1,2-oligomannosides reacted with two different factor sera depending on the degree of polymerization and the nature of the mannose residues at the reducing end. Factor serum 5 epitopes are homopolymers of β-1,2-linked mannose present in the mannan acid-labile fraction of serotypes A and B (33). Factor serum 6 has been shown to correspond to one or two β-mannose residues at the nonreducing end of α-1,2-linked lateral chains of the mannan acid-stable region and is specific for serotype A (22). Along with factor serum 13b, which is reactive with some serotype B strains (36), this factor serum allows discrimination of C. albicans serotypes A and B, which differ in adhesins, epidemiology, and resistance to antifungal drugs (1, 3, 16, 28). A large number of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) generated against C. albicans have been shown to react with β-1,2-oligomannosides (15, 37, 39). Immunofluorescence or electron microscopy studies involving anti-β-1,2-oligomannoside MAbs have demonstrated the highly heterogeneous expression of β-1,2-oligomannoside epitopes inside a colony, between morphotypes, or between cells of the same morphotype (either hyphae or yeasts) (10, 13, 29, 38). One of the reasons for this complex expression is that C. albicans β-1,2-oligomannosides not only are present in mannan but are also associated with other carrier molecules. These molecules include mannoproteins and a glycolipid, phospholipomannan (PLM) (37, 40), which is expressed at and shed from the C. albicans cell surface (18).

As growth temperature has been reported to modify mannan β-1,2-mannosylation (30), the effect of growth temperature on the expression of these epitopes on all classes of mannoglyconjugates from C. albicans serotypes A and B was investigated by Western blotting by using a panel of MAbs specific for β-1,2-oligomannosides. C. albicans strains were grown for 24 h on Sabouraud's dextrose agar at 28 or 37°C unless indicated otherwise. Whole-cell extracts used in most experiments were obtained by using the standard AERC (alkaline extraction in reducing conditions) procedure (39). Cell extracts were resolved by the method of Laemmli (23) on 5 to 15% or 7 to 20% acrylamide gels at a constant current. Electrophoresis was performed on mini-slabs (7 by 8 cm) and on standard slabs (14 by 15 cm) for better resolution by using 40 and 70 μg of protein, respectively, per lane. Gels were then electroblotted in a semidry apparatus onto a nitrocellulose sheet (Schleicher and Schuell, Dassel, Germany), stained with Ponceau S, and blocked, and the contents were revealed with the appropriate MAb as described previously (8); skim milk was added at each step to eliminate nonspecific reactions. The MAbs used in this study at concentrations of 2 to 3 μg/ml were selected on the basis of their specificity for β-1,2-oligomannosides (15, 25, 37, 39) and were kindly provided by different research laboratories. MAb AF1, a mouse immunoglobulin M (IgM), was obtained from A. Cassone (Istituto Superiore di Sanita, Rome, Italy). MAbs 10G and B6.1, mouse IgMs, were obtained from the laboratory of one of us (J. E. Cutler), and MAbs DF9-3 and DJ-8 were obtained from M. Borg-von-Zepelin (Zentrum für Hygiene and Humangenetik, Göttingen, Germany). MAb 5B2, a rat-mouse IgM hybrid, was produced in our laboratory. Some information is available on the epitopes recognized by some of these MAbs. MAb 5B2 reacts with a small mannobiose epitope and with longer chains of β-1,2-linked mannose homopolymers or heteropolymers (i.e., serum factors 5 and 6). All other MAbs have a reactivity similar to that of factor 5 (chains of homopolymers of β-1,2-linked mannose with a degree of polymerization greater than two).

Growth temperature affects β-1,2-mannosylation of mannoproteins and PLM of C. albicans serotype A.

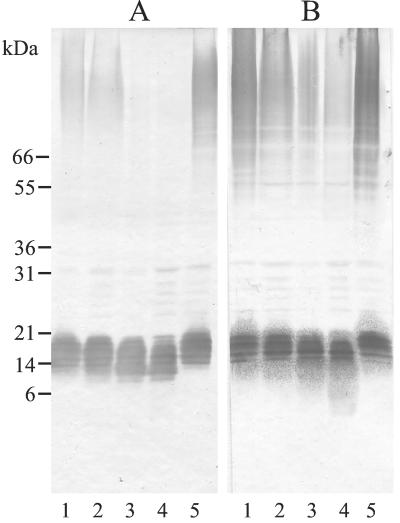

Figure 1 shows the distribution of β-1,2-oligomannoside epitopes after incubation of C. albicans strain VW32 serotype A for 24 h at 28, 37, 39, and 41°C following 24 h of preincubation at the same temperature (lanes 1 to 4). When MAb DF9-3 was used (Fig. 1A), labeling of high-molecular-weight mannoproteins (HMWMPs) decreased, and it was completely absent at growth temperatures above 37°C. This effect of growth temperature was shown to be reversible since 24 h of incubation at 28°C after incubation at 41°C restored the 28°C-specific pattern (Fig. 1A, compare lane 5 with lanes 4 and 1), showing that the alteration was not the result of a permanent genetic change. In contrast, temperature had no effect on the intensity of PLM labeling, but a decrease in the relative molecular weight (Mr) was observed, which was also reversible following subculture at 28°C. With MAb 5B2 (Fig. 1B), an important decrease in HMWMP staining was observed, as well as constant PLM reactivity associated with an increased shift in Mr observed as a faint lower region in the smear.

FIG. 1.

Effect of growth conditions on the expression of β-1,2-linked mannose epitopes on C. albicans glycoconjugates. C. albicans VW32 (serotype A) was preincubated and then incubated for 24 h at 28°C (lanes 1), 37°C (lanes 2), 39°C (lanes 3), or 41°C (lanes 4) on Sabouraud's agar. The preparation in lanes 5 was preincubated at 41°C and then incubated at 28°C. Electrophoretic separation of the AERC extracts was performed on 5 to 15% acrylamide mini-gels. (A) Contents revealed with MAb DF9-3; (B) contents revealed with MAb 5B2.

Growth temperature has similar effects on β-1,2-mannosylation in both C. albicans serotypes, but PLM from serotype B strains have a consistently lower Mr than PLM from serotype A strains.

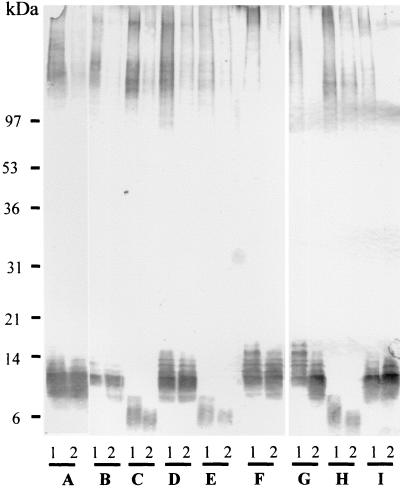

To extend the analysis of β-1,2-mannosylation of glycoconjugates to other strains, C. albicans reference strains or clinical strains of both serotypes were used. The clinical strains originated from blood cultures and were chosen because of unambiguous serotyping results obtained with the Iatron kit. The strains were grown at 28 and 37°C. For both serotypes, Western blot screening of β-1,2-oligomannoside expression revealed that the expression of MAb DF9-3 epitopes on HMWMP from cells grown at 28°C was reduced dramatically when the same strains were grown at 37°C (Fig. 2). Increasing the temperature from 28 to 37°C also resulted in a slight shift in the Mr of PLM, but the most striking observation was that PLM from serotype B strains consistently had lower Mr than PLM from serotype A strains whatever the temperature. Analysis of the changes in Mr was facilitated by the use of more concentrated acrylamide gels, which allowed better separation and approximation of the molecular mass of PLM. Molecular mass is generally overestimated for glycolipids (42) and is fixed at 2 to 4 kDa for serotype A strains (40; unpublished results). Thus, in contrast to previous studies of mannan (21, 31), neither pH (38) nor growth temperature (as shown here) has a drastic effect on PLM mannosylation. Similarly, the difference in the Mr of PLM of the two serotypes seen here seems to be independent of growth conditions that affect protein mannosylation.

FIG. 2.

Western blot analysis of AERC extracts from C. albicans serotypes A and B grown at 28°C (lanes 1) or 37°C (lanes 2) for 24 h on Sabouraud's agar. Reference strains and strains isolated from positive blood cultures were used. The serotype A strains used were C. albicans NIH A 207 (A), C. albicans 4224 (B), C. albicans 517 (D), C. albicans ATCC 10261 (F), C. albicans ATCC 32354 (G), and C. albicans VW32 (I). The serotype B strains used were C. albicans 6780 (C), C. albicans 8252 (E), and C. albicans ATCC 90028 (H). AERC extracts were obtained by the standard procedure. Large 7 to 20% acrylamide gels were used to allow better resolution of the samples, and β-1,2-mannosylation of glycoconjugates was revealed with MAb DF9-3.

Temperature-dependent β-1,2-mannosylation also involves cell wall-associated mannoproteins and PLM in both serotypes of C. albicans.

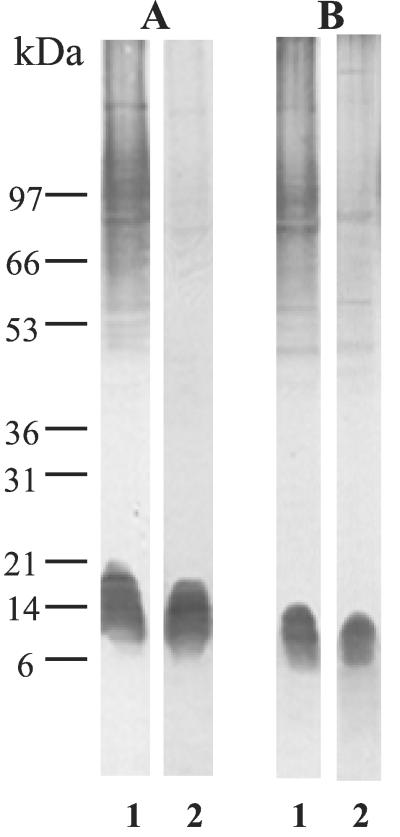

To assess whether the differences in β-1,2-mannosylation of C. albicans glycoconjugates from whole-cell extracts related to growth temperature and serotype also involved the host-parasite interface, cell wall extracts were produced. Zymolyase extracts from C. albicans strains VW32 and NIH B 792 grown at 28 or 37°C in Sabouraud's broth were prepared as described by Li and Cutler (24), except that 40 U of Zymolyase and a 45-min incubation period were used. After treatment, cells were harvested, and the supernatants were filtered through GF-F membranes, dialyzed, and concentrated. Analysis of these Zymolyase extracts (Fig. 3) showed that increasing the temperature resulted in a reduction in β-mannosylation of cell wall mannoproteins. Whatever the C. albicans serotype, PLM β-mannosylation was not affected by temperature, and PLM represented the major C. albicans cell wall mannoglycoconjugate carrying β-1,2-oligomannosides at 37°C. For both serotypes, the Mr of PLM was slightly lower at 37°C, but cell wall PLM from serotype A had a higher Mr than serotype B PLM at all temperatures tested.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of cell wall extracts from C. albicans strains VW32 (serotype A) (A) and NIH B 792 (serotype B) (B) grown at 28°C (lanes 1) or 37°C (lanes 2) in Sabouraud's broth. Cells were first sensitized for 30 min with 0.3 M β-mercaptoethanol and then treated with Zymolyase 20T (40 U/g [wet weight] of cells) for 45 min at 37°C. Acrylamide mini-gels (7 to 20% acrylamide) and MAb DF9-3 were used for separation and detection of glycoconjugates, respectively.

Differences in Mr of PLM from C. albicans serotypes A and B were confirmed with a panel of anti-β-1,2-oligomannoside antibodies.

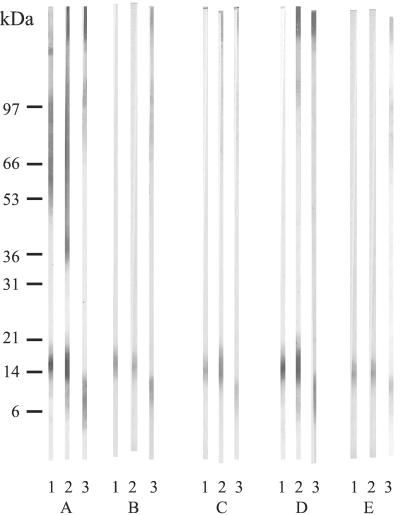

The differences in the Mr of PLM from the two C. albicans serotypes were confirmed by using three references strains and five anti-β-1,2-oligomannosides MAbs (Fig. 4). With these strains, particularly the serotype A strains, more intense staining of mannoproteins by MAb 5B2 was observed, some of which corresponded to the staining with MAb B9.E, an anti-serotype A MAb (data not shown). This pattern is consistent with MAb 5B2 reactivity starting from short β-1,2-oligomannosides, which are present both in the acid-stable fraction of serotype A mannan as heteropolymers and in the acid-labile fraction of serotype A and B mannans as homopolymers. This ability of MAb 5B2 to reveal all β-1,2-oligomannosides, including those with a low degree of polymerization, may also explain the specific ability of this MAb to reveal lower parts of the PLM smear, particularly for serotype B, which may consist of shorter oligomannose chains.

FIG. 4.

Comparative analysis of the reactivities of MAbs 5B2 (A), DJ2-8 (B), DF9-3 (C), 10G (D), and AF1 (E) specific for β-1,2-oligomannosides in AERC extracts from C. albicans strain VW32 (serotype A) (lanes 1), strain NIH A 207 (serotype A) (lanes 2), and strain NIH B 792 (serotype B) (lanes 3). Cells were grown at 28°C on Sabouraud's agar, and 7 to 20% acrylamide gels were used.

Differences in Mr of PLM between serotypes A and B are also associated with antigenic differences independent of the growth temperature.

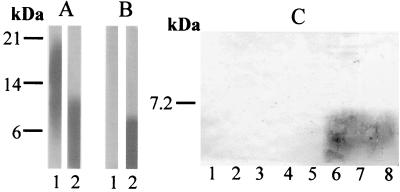

Of the MAbs tested, MAb B6.1, which recognizes a small mannotriose epitope but also has a restricted affinity for higher degrees of polymerization (15), exhibited a reactivity specific for PLM from serotype B strains. As shown in Fig. 5, this reactivity mainly concerned the lower part of PLM (Fig. 5B, lane 2). The epitope was not temperature dependent, and the selective reactivity was confirmed with different strains of both serotypes (Fig. 5C). The specificity of MAb B6.1 may be related to its restricted recognition domain. The degree of polymerization of PLM, which appeared to be higher in serotype A strains than in serotype B strains, may thus prevent the binding of this MAb.

FIG. 5.

Divergent reactivities of MAb B6.1 with PLM from serotype A and B strains. (A) MAb DJ2-8, used as a control, reacted with PLM from both serotype A strain VW32 (lane 1) and serotype B strain NIH B 792 (lane 2). (B) MAb B6-1 reacted with PLM from the serotype B strain (lane 2) but not with PLM from the serotype A strain (lane 1). (C) Confirmation of the selective reactivity of MAb B6-1 with PLM from serotype B strains (lane 6, strain ATCC 90028; lane 7, strain 6780; lane 8, strain 8252). PLM from serotype A strains were unreactive (lane 1, strain VW32; lane 2, strain NIH A 207; lane 3, strain ATCC 32354; lane 4, strain ATCC 10261; lane 5, strain 8252). Cells were grown at 37°C on Sabouraud's agar. The panel A and B blots were revealed by using the enhanced chemiluminescence technique (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) and exposure on ECL hyperfilm. The panel C blot was revealed by using standard conditions (8).

Current research in molecular and cell biology suggests that the versatility of C. albicans contributes to its status as an important human pathogen (7). More generally, variability in glycosylation is recognized as a fast cellular pathway to respond to environmental changes. In this study, C. albicans β-1,2-oligomannosides, which act as adhesins (12, 25) and inducers of cytokines (19) and protective antibodies (14), were shown to be differentially expressed on glycoconjugates in response to environmental change. This results in the presentation at the yeast cell surface of different carrier molecules (either lipids or proteins) which could, in turn, induce different responses from the host cells and immune system.

Differentiation between C. albicans serotypes is based on the presence of β-1,2-oligomannosides in serotype A mannan. Serotyping methods have been used for epidemiological studies for a long time and have revealed differences in the geographic distributions of different strains (5) and their abilities to infect immunocompetent or immunocompromised patients (6, 11, 27). However, immunochemical studies have shown that serotype A strains do not express antigen 6 when they are grown at a low pH or a high temperature. Conversely, studies performed with polyclonal antibodies from immunized or infected rabbits have shown that serotype B strains may gain factor 6 (specific for serotype A) in vivo and produce germ tubes that express antigen 6 (32). This observation was confirmed by using an MAb (2). Other experiments have shown that acellular extracts of serotype B cells contain enzymes (mannosyl transferases) required for the construction of serotype A epitopes (35). These experimental data showed that serotype expression in C. albicans is phenotypic rather than genotypic. Thus, in contrast to previous studies of serotype A epitopes, C. albicans serotypes A and B seem to display PLM with phenotypically stable differences in their electrophoretic and antigenic properties. This preliminary observation, which suggests that there may be a genetic basis of antigen expression, is in agreement with recently identified relationships between serotypes and genotypes (3, 16).

All the results obtained in this study by using strains that gave unambiguous results with the standard serotyping method were clear-cut and highly reproducible (i.e., higher Mr and lack of reactivity of serotype A PLM with MAb B6.1 and lower Mr and reactivity of serotype B PLM with MAb B6.1). However, as stressed in a previous study (4), some C. albicans strains were found which gave inconsistent serotyping results (inconsistent and very weak reactivity with factor 6). These atypical strains presented PLM with serotype A characteristics (higher Mr and lack of reactivity with MAb B6.1).

Structural and biological characterization of serotype B PLM is in progress. These studies are complementary to genetic studies of C. albicans mannosyl transferases and phosphomannose transferases (so far unknown) and aim to define the nature of the mechanism(s) involved in antigen expression and whether the mechanism(s) is related to parasitic adaptation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bernadette Leu and Annick Masset for their expert technical assistance and Valerie Hopwood for improvement of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Programme de Recherche Fondamentale en Microbiologie, Maladies Infectieuses et Parasitaires.

Editor: T. R. Kozel

REFERENCES

- 1.Auger, P., C. Dumas, and J. Joly. 1979. A study of 666 strains of Candida albicans: correlation between serotype and susceptibility to 5-fluorocytosine. J. Infect. Dis. 139:590-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barturen, B., J. Bikandi, R. San Millan, M. D. Moragues, P. Regulez, G. Quindos, and J. Ponton. 1995. Variability in expression of antigens responsible for serotype specificity in Candida albicans. Microbiology 141:1535-1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastide, J. M., C. Pujol, M. Maillie, and J. Reynes. 1999. Genotype, serotype and sensitivity to fluconazole of Candida albicans strains isolated from HIV-positive patients. Bull. Natl. Acad. Med. 183:289-302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brawner, D. L. 1991. Comparison between methods for serotyping of Candida albicans produces discrepancies in results. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:1020-1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brawner, D. L., G. L. Anderson, and K. Y. Yuen. 1992. Serotype prevalence of Candida albicans from blood culture isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:149-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brawner, D. L., and J. E. Cutler. 1989. Oral Candida albicans isolates from nonhospitalized normal carriers, immunocompetent hospitalized patients, and immunocompromised patients with or without acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:35-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calderone, R., and W. Fonzi. 2001. Virulence factors of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol. 9:327-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cantelli, C., P. A. Trinel, A. Bernigaud, T. Jouault, L. Polonelli, and D. Poulain. 1995. Mapping of beta-1,2-linked oligomannosidic epitopes among glycoconjugates of Candida species. Microbiology 141:2693-2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Bernardis, F., M. Boccanera, D. Adriani, E. Spreghini, G. Santoni, and A. Cassone. 1997. Protective role of antimannan and anti-aspartyl proteinase antibodies in an experimental model of Candida albicans vaginitis in rats. Infect. Immun. 65:3399-3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faille, C., J. C. Michalski, G. Strecker, D. W. Mackenzie, D. Camus, and D. Poulain. 1990. Immunoreactivity of neoglycolipids constructed from oligomannosidic residues of the Candida albicans cell wall. Infect. Immun. 58:3537-3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flores de Apodaca Verdura, Z., G. Martinez Machin, A. Ruiz Perez, C. M. Fernandez Andreu, M. Mune Jimenez, and M. Perurena Lancha. 1998. Esophageal candidiasis in AIDS patients. A clinical and microbiological study. Rev. Cubana Med. Trop. 50:110-114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fradin, C., T. Jouault, A. Mallet, J. Mallet, D. Camus, P. Sinaÿ, and D. Poulain. 1996. β-1,2-Linked oligomannosides inhibit Candida albicans binding to murine macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 60:81-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fruit, J., J. C. Cailliez, F. C. Odds, and D. Poulain. 1990. Expression of an epitope by surface glycoproteins of Candida albicans. Variability among species, strains and yeast cells of the genus Candida. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 28:241-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goins, T. L., and J. E. Cutler. 2000. Relative abundance of oligosaccharides in Candida species as determined by fluorophore-assisted carbohydrate electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2862-2869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han, Y., T. Kanbe, R. Cherniak, and J. E. Cutler. 1997. Biochemical characterization of Candida albicans epitopes that can elicit protective and nonprotective antibodies. Infect. Immun. 65:4100-4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hannula, J., B. Dogan, J. Slots, E. Okte, and S. Asikainen. 2001. Subgingival strains of Candida albicans in relation to geographical origin and occurrence of periodontal pathogenic bacteria. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 16:113-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoyer, L. L., T. L. Payne, and J. E. Hecht. 1998. Identification of Candida albicans ALS2 and ALS4 and localization of Als proteins to the fungal cell surface. J. Bacteriol. 180:5334-5343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jouault, T., C. Fradin, P. A. Trinel, A. Bernigaud, and D. Poulain. 1998. Early signal transduction induced by Candida albicans in macrophages through shedding of a glycolipid. J. Infect. Dis. 178:792-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jouault, T., G. Lepage, A. Bernigaud, P. A. Trinel, C. Fradin, J. M. Wieruszeski, G. Strecker, and D. Poulain. 1995. Beta-1,2-linked oligomannosides from Candida albicans act as signals for tumor necrosis factor alpha production. Infect. Immun. 63:2378-2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanbe, T., and J. E. Cutler. 1998. Minimum chemical requirements for adhesin activity of the acid-stable part of Candida albicans cell wall phosphomannoprotein complex. Infect. Immun. 66:5812-5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobayashi, H., P. Giummelly, S. Takahashi, M. Ishida, J. Sato, M. Takaku, Y. Nishidate, N. Shibata, Y. Okawa, and S. Suzuki. 1991. Candida albicans serotype A strains grow in yeast extract-added Sabouraud liquid medium at pH 2.0, elaborating mannans without beta-1,2 linkage and phosphate group. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 175:1003-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi, H., N. Shibata, and S. Suzuki. 1992. Evidence for oligomannosyl residues containing both beta-1,2 and alpha-1,2 linkages as a serotype A-specific epitope(s) in mannans of Candida albicans. Infect. Immun. 60:2106-2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, R. K., and J. E. Cutler. 1991. A cell surface/plasma membrane antigen of Candida albicans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:455-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, R. K., and J. E. Cutler. 1993. Chemical definition of an epitope/adhesin molecule on Candida albicans. J. Biol. Chem. 268:18293-18299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masuoka, J., and K. C. Hazen. 1999. Differences in the acid-labile component of Candida albicans mannan from hydrophobic and hydrophilic yeast cells. Glycobiology 9:1281-1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendling, W., and U. Koldovsky. 1996. Immunological investigations in vaginal mycoses. Mycoses 39:177-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyakawa, Y., T. Kuribayashi, K. Kabaya, M. Suzuki, T. Nakase, and Y. Fukasawa. 1992. Role of specific determinants in mannan of Candida albicans serotype A in adherence to human buccal epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 60:2493-2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Molinari, A., M. J. Gomez, P. Crateri, A. Torosantucci, A. Cassone, and G. Arancia. 1993. Differential cell surface expression of mannoprotein epitopes in yeast and mycelial forms of Candida albicans. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 60:146-153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okawa, Y., K. Goto, S. Nemoto, M. Akashi, C. Sugawara, M. Hanzawa, M. Kawamata, T. Takahata, N. Shibata, H. Kobayashi, and S. Suzuki. 1996. Antigenicity of cell wall mannans of Candida albicans NIH B-792 (serotype B) strain cells cultured at high temperature in yeast extract-containing Sabouraud liquid medium. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 3:331-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okawa, Y., T. Takahata, M. Kawamata, M. Miyauchi, N. Shibata, A. Suzuki, H. Kobayashi, and S. Suzuki. 1994. Temperature-dependent change of serological specificity of Candida albicans NIH A-207 cells cultured in yeast extract-added Sabouraud liquid medium: disappearance of surface antigenic factors 4, 5, and 6 at high temperature. FEBS Lett. 345:167-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poulain, D., G. Tronchin, A. Vernes, R. Popeye, and J. Biguet. 1983. Antigenic variations of Candida albicans in vivo and in vitro—relationships between P antigens and serotypes. Sabouraudia 21:99-112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shibata, N., M. Arai, E. Haga, T. Kikuchi, M. Najima, T. Satoh, H. Kobayashi, and S. Suzuki. 1992. Structural identification of an epitope of antigenic factor 5 in mannans of Candida albicans NIH B-792 (serotype B) and J-1012 (serotype A) as beta-1,2-linked oligomannosyl residues. Infect. Immun. 60:4100-4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soll, D. R. 1992. High-frequency switching in Candida albicans. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 5:183-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suzuki, A., Y. Takata, A. Oshie, A. Tezuka, N. Shibata, H. Kobayashi, Y. Okawa, and S. Suzuki. 1995. Detection of beta-1,2-mannosyltransferase in Candida albicans cells. FEBS Lett. 373:275-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suzuki, S. 1997. Structural investigation of mannans of medically relevant Candida species; determination of chemical structures of antigenic factors 1, 4, 5, 6, 9 and 13b, p. 1-15. In S. Suzuki and M. Suzuki (ed.), Fungal cells in biodefense mechanism. Saikon Publishing Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan.

- 37.Trinel, P. A., M. Borg-von-Zepelin, G. Lepage, T. Jouault, D. Mackenzie, and D. Poulain. 1993. Isolation and preliminary characterization of the 14- to 18-kilodalton Candida albicans antigen as a phospholipomannan containing beta-1,2-linked oligomannosides. Infect. Immun. 61:4398-4405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trinel, P. A., C. Cantelli, A. Bernigaud, T. Jouault, and D. Poulain. 1996. Evidence for different mannosylation processes involved in the association of beta-1,2-linked oligomannosidic epitopes in Candida albicans mannan and phospholipomannan. Microbiology 142:2263-2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trinel, P. A., C. Faille, P. M. Jacquinot, J. C. Cailliez, and D. Poulain. 1992. Mapping of Candida albicans oligomannosidic epitopes by using monoclonal antibodies. Infect. Immun. 60:3845-3851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trinel, P. A., Y. Plancke, P. Gerold, T. Jouault, F. Delplace, R. T. Schwarz, G. Strecker, and D. Poulain. 1999. The Candida albicans phospholipomannan is a family of glycolipids presenting phosphoinositolmannosides with long linear chains of beta-1,2-linked mannose residues. J. Biol. Chem. 274:30520-30526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsuchiya, T., M. Takaguchi, Y. Fukazawa, and T. Shinoda. 1984. Serological characterization of yeasts as an aid in identification and classification. Methods Microbiol. 16:75-126. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Venisse, A., J. M. Berjeaud, P. Chaurand, M. Gilleron, and G. Puzo. 1993. Structural features of lipoarabinomannan from Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Determination of molecular mass by laser desorption mass spectrometry. J. Biol. Chem. 268:12401-12411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]