Palliative and supportive care differ in philosophy from curative strategies in focusing primarily on the consequences of a disease rather than its cause or specific cure. Approaches are therefore necessarily holistic, pragmatic and multidisciplinary and there is almost no philosophical distinction between palliation and support. The approach therefore complements oncological or antiviral treatments; it does not substitute for or replace them.

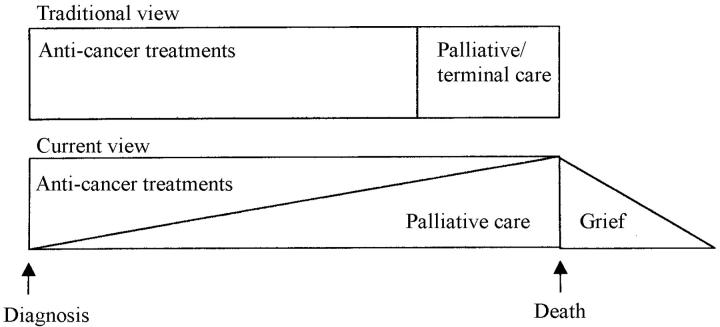

The old view was that palliative care and hospice services apply only to those who are dying, but in reality palliative care is often needed from the time of diagnosis. Evidence that the cost-efficacy of palliative care far outweighs attempts at disease cure, in terms of quality of life for the individual and family1, has changed the emphasis in the UK towards services working in parallel with other specialties, earlier in the disease. Simultaneously palliative care services have acquired an increasing role in incurable diseases apart from cancer, and a further task is to ensure that bereavement care is provided to those at risk of complicated grief. This development can be represented by the diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Traditional and current views of palliative/terminal care

HISTORY OF A DEVELOPING POLICY FRAMEWORK

After much public discussion about the inequalities in cancer treatment around the UK, an Expert Advisory Group on Cancers was established at the Department of Health to provide direction on the development and organization of cancer services in England and Wales. In 1995 the group published its report, under the joint chairmanship of the Chief Medical Officers for England (Dr Kenneth Calman) and Wales (Dr Deirdre Hine), commonly known as the Calman-Hine report2. A similar report was then published in Scotland. Calman-Hine outlined the need for multiprofessional specialist palliative care teams, stating:

‘Palliative care should not be associated exclusively with terminal care. Many patients need it early in the course of their disease, sometimes from the time of diagnosis. The palliative care team should integrate in a seamless way with all cancer treatment services to provide the best possible quality of life for the patient and their family. The palliative care services should work in close collaboration with their colleagues at the Cancer Centre and be involved in regional audit and developing integrated operational policies and protocols.

‘Although much palliative and terminal care is provided in the community by primary care teams, each district must have a specialist resource for both primary care and hospital based services. This facility should work with local hospital oncology services and with primary care teams to allow good communications and rapid access to specialised palliative treatments for symptom control, to provide respite care and to give psychosocial support to the patient and family at all stages, including bereavement. By this means, there should be a smooth progression of care between home, hospital and hospice.

‘The multi-disciplinary palliative care team should contain trained specialist medical and nursing staff, social workers, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and should relate to other disciplines such as dietetics and chaplaincy’.

The Calman-Hine report set out a policy framework for the commissioning of cancer services. The document went on to highlight the need for planning since hospice units had developed in an ad hoc manner, not necessarily in areas of greatest need. Although the report focused on cancer, the subsequent government executive letter3 recognized that palliative care is required by patients with any progressive life-limiting disease, so that the principles outlined applied also to those with AIDS, motor neuron disease, end-stage cardiorespiratory failure and so on. Most of the crucial strategic developments have taken place in relation to cancer care provision, but data from cancer workload alone underestimate the need for the services. The report recognized the specialist nature of palliative care provision and declared skills in a palliative care approach to be a core requirement of every health professional.

Plans for implementation of the report varied across regions. Historically, palliative care services had arisen from voluntary sector fundraising efforts. It was not until the late 1970s that government funding was given to support hospices; hospices funded by the National Health Service (NHS) then joined those funded by Marie Curie Cancer Care, Sue Ryder Foundation and other independent charities. Thus the main drive to hospice development has come from the non-statutory sector and has often resulted in the ad hoc development of services which the NHS was then asked to support. There were early attempts to establish a strategic development plan in Wales, but political climate changes made this difficult to implement. The Standing Medical and Standing Nursing Advisory Committees also published joint guidance on palliative care services prior to the Calman-Hine report, but it was the link of palliative care to cancer services in Calman-Hine that had the main influence on integration of the specialty into the NHS.

Regional implementation groups were then established and they began to look at and plan cancer service development in their own areas. Each region worked on its own cancer services plan; in Wales the proximity of government (the Welsh Office) to the NHS health authorities allowed close working relationships at a strategic level. For example, the Cancer Services in Wales report4 outlined the staffing levels and strategies required for all aspects of cancer services. The Welsh Office document Palliative Care in Wales: Towards Evidence Based Purchasing5 established a framework for the development of local policies and recommended closer working links between agencies. It also advised on protocols for referral and had four key themes to its recommendations:

Equity of access to palliative care services of a high standard

Adequate, appropriate and widely available information to patients

Support for research

Increased training of all existing staff to provide care with a palliative approach.

CURRENT SERVICES

For the following information I am indebted to the St Christopher's Hospice Information Service. In the UK and the Republic of Ireland there are currently 223 inpatient units (with 3253 beds), 234 day-care centres, 408 home care teams, 139 hospital support teams and 176 hospital support nurses6. There are 50.8 beds/million population in England, 67.4 in Scotland, 38.5 in Northern Ireland and 42.3 in Wales. Just 72 beds are specifically for patients with HIV/AIDS (Table 1).

Table 1.

UK palliative care services exclusively for HIV/AIDS

| Beds n=72 | Day care | Home care | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brighton | 12 | Yes | ||

| Edinburgh | 16 | Yes | Information | |

| London Central | ||||

| London Kensington & Chelsea | Information | |||

| London Tower Hamlets | 44 | Yes | Hospital support |

KEY STRATEGIC DOCUMENTS

The Health Services Circular Improving the Quality of Cancer Services7 has set standards for cancer services. It states that every health authority must ensure that high-quality specialist palliative care services are provided both in hospitals and in the community for all patients who need them through:

Development and implementation of appropriate strategies across networks and within individual cancer centres and cancer units as well as in the community

Provision of multidisciplinary specialist palliative care teams across all sectors, which meet regularly to review individual patient care.

Documents have also been produced in the different regions in England to guide the inspection of palliative care services for national accreditation. In Wales the process has been a little different, with minimum standards set for cancer services, which are being revisited each year to ensure they are met.

The type of service delivered around England and Wales varies, as evident from the 1999 Directory of Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services6. This variation has been recognized in the NHS Cancer Plan8 for England which states that only one-third of health authorities have developed strategies for specialist palliative care provision and that services are uneven. Some regions have twice as many specialist palliative care beds, whether in a voluntary hospice or in a specialist NHS unit, as others. The same is true for home care nurses. The document declares:

‘All patients should have access to the specialist palliative care advice and services that they need. For most patients, these will be provided in their homes, in the community or in hospital. Some will require the specialist facilities of a hospice. Voluntary palliative care services need to be enabled to play their full role in the cancer network, with adequate funding from the NHS.’

An attempt was made to define the different types of service in Palliative Care 2000, a document for purchasers produced by the National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services in England, Wales and Northern Ireland9. The outline in this does not fit well with the type of service in rural areas, where several teams are nurse-only, or where medical recruitment has failed. Gwent Health Authority developed an alternative model of definitions10 which has been adopted and modified by the All Wales Executive Committee of the National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services. This outlines three levels of service—specialist, intermediate and generalist.

Specialist services

These contain one or more doctors who have undergone higher specialist training or are on the specialist register in palliative medicine, plus one or more nurses who have undergone higher specialist training. At least one professional attached to the team is from a profession allied to medicine and this person has had some further training in palliative care to equip him/her for the role. These services will be providing care at both complex and intermediate levels.

Intermediate services

One model for these is staffed by professionals from differing disciplines working full-time or most of the time in palliative care, but who have not undergone any higher specialist training. They have developed much clinical experience over the years and will have had in-service training for their job. An alternative model is a unidisciplinary team of professionals (nurses) working full-time or most of the time in palliative care, in which one or more members may have had some further training. These nurses work with general practitioners, some of whom may have additional training in the subject, such as the Diploma in Palliative Medicine from University of Wales College of Medicine. Care is provided in designated community beds as part of community hospitals or nursing homes, or in the patient's own home.

Generalist services

Generalist services are concerned with the care of patients in the palliative/terminal phase of their illness, but this is not the main focus of their workload.

STAFFING REQUIREMENTS

The Royal College of Physicians instigated higher specialist medical training in palliative care medicine after recognition of the specialty in 1989. Since then, training has been regulated through the Joint Committee on Higher Medical Training11, with educational placements and designated training numbers in each region. However, training to a higher specialist level in nursing and other disciplines is not yet defined in a regulatory framework.

The training to specialist level in the UK is a four-year programme in educationally approved placements. The number of trainees is closely controlled nationally and at present the supply of trainees lags seriously behind the current demand for specialists. Training is carefully monitored and reviewed; any trainee not reaching the required levels of competency is referred for targeted training. The four years consists of at least two years in a specialist service plus up to one year's research and up to one year in related placements such as oncology, infectious diseases (HIV/AIDS), cardiology or haematology. This process has meant that those applying for consultant posts are properly trained and able to sustain that level of responsibility, but the limitation of funding for trainees has resulted in a shortfall of those eligible to apply for consultant posts.

MEDICAL STAFF

Different formulae have been used to calculate the staff required for multiprofessional palliative care. The figures have been calculated from the 95% workload related to cancer, allowing for a 20% increase for AIDS, cardio-respiratory failure and neurological diseases. However, the increasing pressure to take those with cancer earlier and also to take those with a non-cancer diagnosis is pushing the requirements up by about 36% (All Wales Palliative Medicine Discussion Group, unpublished). Additionally, the amount of teaching by consultants in palliative medicine has increased dramatically. All medical schools in the UK have it as a core subject on the curriculum, with many places also providing special study modules in the subject and using small-group teaching. In Cardiff the team undertake about 112 sessions of undergraduate teaching per annum, with a further 14 sessions by each of the specialist palliative care teams in Wales during community clinical attachments.

According to the Cameron Report4 a population base of 200 000 requires, for community only, 1 whole-time-equivalent (WTE) consultant in palliative medicine, 3 WTE specialist nurses (community), 0.5 WTE dedicated social work input, and physiotherapy and occupational therapy available to the palliative care team for one session a week. Hospitals with cancer units require 3-5 sessions of consultant palliative medicine time plus 1 specialist nurse.

Consultant requirements in palliative medicine, as submitted by the Association for Palliative Medicine to the Royal College of Physicians, were calculated from the baseline of a resident population of 80 000 around a district general hospital and an estimate of 20% non-cancer referrals. Extrapolation for the UK as a whole, based on the work done by consultants in palliative medicine12, suggests a need for 375 WTE of consultant time in the UK. If the figures are recalculated to allow for the 36% expected increase arising from non-cancer referrals and the earlier involvement in care, the number rises to 435 WTE, or 1.5 WTE for a population base of 200 000.

However, a calculation for Wales suggests that the shortfall in consultants will not improve without increased finance for training places. The current shortfall of 13 consultants will not begin to lessen until 2021, when the deficit will be 8. There are good applicants for the training posts, but many juniors are becoming disillusioned as they get stuck at senior house officer grade owing to the bottleneck in training posts. Such detailed calculations do not seem to have been done for other staff in the team but current data suggest increasing pressure on palliative care services, just as there is on acute services across the UK.

EVIDENCE OF EFFICACY OF SPECIALIST PALLIATIVE CARE

A systematic review was commissioned by Wales Office for Research and Development to examine the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of palliative care teams (now accepted as a Cochrane Review)13. Overall, this literature review found evidence of benefit in terms of patient and carer outcomes. The work suggests that home care is not less expensive than inpatient hospice care. The dearth of research in this area points to the need for more evaluation of services, measurement of outcomes and assessment of economic effects. The report recommends that hospice and specialist palliative care services be supported by the NHS as an effective method of caring for patients in advanced illness. It also calls for evaluation of different models of palliative care team and the relative merits of hospital, home and inpatient hospice support. Analysis of the type of care delivered by different teams suggest better outcomes with full specialist and intermediate level teams than with generic care.

CURRENT STRATEGIC DOCUMENTS IN ENGLAND

Since devolution, the Welsh have diverged increasingly from the English mode of service development. A draft strategic plan for palliative care has been written for England for 2000-2005. It recommends decreased reliance on charitable funds to provide core specialist services and closer integration of palliative care with other treatment services. It suggests that managed networks of palliative care services will coordinate: access to care and the development of care pathways, for patients with various diseases who can benefit from palliative care, through links with other relevant local networks (e.g. for cancer, HIV/AIDS) and with emerging networks for patients with cardiac disease; configuration of services across catchment populations; a programme for monitoring the quality of care; strategic investment proposals to ensure the inclusion and financing of palliative and supportive care strategies in local health improvement programmes; and training and research development to include educational programmes for health and social care providers, and for patients, about palliative care services

A crucially important document in England has been the NHS Cancer Plan8, which includes palliative care services. This document recognizes that the major contribution (about £170 million per annum) to clinical palliative care services to date has come from the voluntary sector: ‘for too long the NHS has regarded specialist palliative care as an optional extra. So by 2004 the NHS will invest an extra £50 million to end inequalities in access to specialist palliative care... NHS investment in specialist palliative care services will match that of the voluntary sector.’

It outlines the need for the charitable sector to become more integrated with the NHS, through managed networks of care. It states that palliative care services must work to agreed national standards if they are to be funded on a 50% basis rather than the 33% NHS funding that currently applies. A palliative and supportive care strategy is written for England (full text available on the Department of Health website), and a manual of cancer services assessment standards includes palliative care provision in its core framework14.

THE FUTURE OF STANDARDS AND MONITORING

The increase in defined standards and in National Service Frameworks within which care is to be delivered will certainly drive the criteria against which the services are funded. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence, responsible for overseeing the implementation of evidence-based practice in the UK, has so far concentrated on drugs but will need to address service developments. Additionally, professional self-regulation, the advent of clinical governance and the need for continual professional development will all influence care delivery and the working patterns of multiprofessional teams.

These standards will be monitored through the Commission for Health Improvement, via the National Performance Frameworks and through the auditing of services from the perspectives of those for whom the service is provided—patients and their carers.

In the UK the recognition of palliative medicine as a specialty and the instigation of a specialist-training programme have meant the integration of services with the NHS. However, the huge amount of charitable money that has been raised may have made NHS managers wary of insisting on the lines of answerability and communication that normally apply within the NHS. The involvement of local politicians and the local press has at times put intolerable pressure on the NHS to support services which have been developed without adequate consultation. Such charities also tend to attract those who are highly motivated but impatient with the bureaucracy of NHS planning.

As palliative care becomes firmly placed as an integral part of cancer services, it needs to be extended to other services. This requires a doubling of the training places available in the UK. Until palliative approaches are integrated into everyday practice, patients will continue to have futile treatments, given at inappropriate times or in inappropriate venues, and families will remain at times bewildered by all that is happening. Palliative care cannot remove the impact of a tragedy, but it can ensure that the patient's voice is heard and the needs are addressed.

References

- 1.O'Neill B, Fallon M. ABC of palliative care. Principles of palliative care and pain control. BMJ 1997;315: 801-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Report of the Expert Advisory Group on Cancers to Chief Medical Officers of England and Wales. London and Cardiff: Department of Health and Welsh Office, 1995

- 3.A Policy Framework for Commissioning Cancer Services: Palliative Care Services. Executive Letter EL(96)85

- 4.Cancer Services in Wales. Cardiff: Cancer Services Co-ordinating Group, Welsh Office, 1996

- 5.Palliative Care in Wales: Towards Evidence Based Purchasing. Cardiff: Welsh Office, 1996

- 6.Directory of Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services. London: Hospice Information Service, St Christopher's Hospice, 1999

- 7.Improving the Quality of Cancer Services. Leeds: NHS Executive, 2000

- 8.The NHS Cancer Plan: a Plan for Investment, a Plan for Reform. Leeds: NHS Executive, 2000

- 9.Palliative Care 2000, a Guide to Commissioning Services. London: National Council for Hospices and Specialist Palliative Care Services, 1999

- 10.Pitman M. Palliative Care Strategy for Gwent. Pontypool: Gwent Health Authority, 1999

- 11.A Guide to Specialist Registrar Training. London: Department of Health, 1998

- 12.Makin W, Finlay IG, Amesbury B, Naysmith A, Tate T. What do palliative medicine consultants do? Pall Med 2000:14; 405-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higginson I, Finlay I, Goodwin DM, et al. The role of palliative care teams: a systematic review of their effectiveness and cost-effectiveness

- 14.Manual of Cancer Services Assessment Standards (consultation document). Leeds: NHS Executive, 2000