Vaginal stones and lost intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUCDs) are commonly reported separately but seldom together.

CASE HISTORY

A woman of 63 had a radiograph taken to evaluate hip pain and was discovered to have an ovoid calcified mass measuring 9 × 5 cm in her pelvis (Figure 1). She was suspected of having a giant bladder stone and was referred by her general practitioner to a urologist.

Figure 1.

Radiograph of pelvis showing calcified mass

The patient, who had three children, had been well until the age of 41 when she had become decerebrate after a 'flulike illness. Brain biopsy showed probable acute allergic leukoencephalitis and for the next three months she was in a vegetative state. Much to the surprise of her carers, she gradually improved and was discharged home after 10 months. Her indwelling catheter had been removed and apart from occasional urinary accidents she was managed satisfactorily with ‘toileting’ and precautionary incontinence pads. Until the present admission she lived at home or in residential care. Characteristically when approached she would subject her family and the medical staff to a colourful stream of invective interspersed with occasional elements of normal speech. She declined examination of any sort. However, if the verbal tirade was ignored, she was entirely cooperative. Occasionally she had needed treatment for urinary tract infections, and these had become chronic in the months before admission.

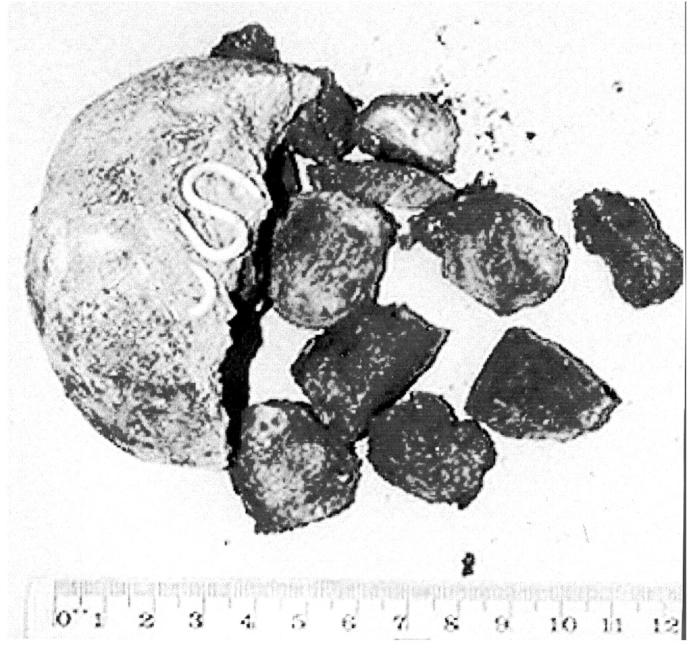

A pelvic ultrasound scan indicated that the mass might not be in the bladder but in the pouch of Douglas. At cystoscopy and examination under annesthesia by the urologist the calculus was found to be in the vagina, but it could not be removed digitally. The patient was referred to the gynaecology department. At the time of a second anaesthetic, despite use of Wrigley's forceps1 and much lubrication, it was still not possible to dislodge the mass intact. The rough surface would not slide over the vaginal mucous membrane without causing soft-tissue damage. It was removed by partial morcellation after episiotomy. In the centre of the laminated structure was a Lippes loop IUCD (Figure 2). Postoperatively the patient received intravenous antibiotics for a Klebsiella urinary tract infection. Six weeks later she had healed and was continent.

Figure 2.

Vaginal stone with embedded device

Probably the Lippes loop had been inserted about 23 years previously after a miscarriage. Since her encephalitis no one had been prepared to do a pelvic examination or had attempted a cervical smear, because of her abusiveness. Analysis of the stone showed it to consist of calcium carbapatite (calcium carbonate and phosphate).

COMMENT

Primary vaginal stones occur where there is stasis of urine and infection, associated with a congenital abnormality such as an ectopic ureter or meningomyelocele2. Secondary stones can arise after surgical damage and may be associated with surgical sutures or other forgotten material placed in the vagina3.

Intrauterine contraceptive devices, even when normally located, tend to form calcareous deposits on their surfaces. These deposits differ between devices. Lippes loops characteristically have ‘mud-cracked incrustations’ and ‘rounded masses’, which form in the surface microenvironment. The masses are rosettes of euhedral crystals with porous tips that under high magnification look like city tower-blocks and are similar in composition to the apatite of dental calculus. Different patterns are observed with copper-bearing devices4.

The combination of a displaced IUCD some time previously, personal neglect and lack of regular pelvic examination permitted the development of the stone in this case. From reports of large calculi in children it is clear that the speed of encrustation can be rapid. Therefore, if the IUCD had been expelled soon after its insertion we would expect the stone to have become apparent sooner. Records made in the recovery period from her encephalitis 22 years earlier indicate that, although she expressed interactive distress very forcefully, she did not show any sign of pain. This lack of awareness of pain probably contributed to the late discovery and large size of the mass.

There have been reports of traumatic erosion of the bladder wall by a bladder calculus5 and of the vaginal wall by a vaginal calculus, both leading to fistula formation6. Cystoscopy and careful vaginal examination under anaesthesia did not reveal such damage in our patient, and her return to near-normal bladder function was impressive. Fortunately there had been only superficial infection and there was no sign of pelvic actinomycosis.

References

- 1.Emge KR. Vaginal foreign body extraction by forceps: a case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992; 167: 514-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ragaviah NV, Devai AI. Primary vaginal stones. J Urol 1980; 123: 771-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalela D, Agarwal R, Mishra VK. Giant vaginolith around an unusual foreign body. Br J Urol 1994; 74: 673-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keith I, Baily R, Berger GS, Method M. Surface changes in intrauterine contraceptive devices. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1985; 152: 69-71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mhiri MN, Amous A, Mezghanni M, et al. Vesico-vaginal fistula induced by an intravesical foreign body. Br J Urol 1988; 62: 271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldstein I, Wise CJ, Tancer ML. A vesicovaginal fistula and intravesical foreign body. A rare case of the neglected pessary. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990; 163: 589-91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]