Abstract

Cruzipain, the major cysteinyl proteinase of Trypanosoma cruzi, is expressed by all developmental forms and strains of the parasite and stimulates potent humoral and cellular immune responses during infection in both humans and mice. This information suggested that cruzipain could be used to develop an effective T. cruzi vaccine. To study whether cruzipain-specific T cells could inhibit T. cruzi intracellular replication, we generated cruzipain-reactive CD4+ Th1 cell lines. These T cells produced large amounts of gamma interferon when cocultured with infected macrophages, resulting in NO production and decreased intracellular parasite replication. To study the protective effects in vivo of cruzipain-specific Th1 responses against systemic T. cruzi challenges, we immunized mice with recombinant cruzipain plus interleukin 12 (IL-12) and a neutralizing anti-IL-4 MAb. These immunized mice developed potent cruzipain-specific memory Th1 cell responses and were significantly protected against normally lethal systemic T. cruzi challenges. Although cruzipain-specific Th1 responses were associated with T. cruzi protective immunity in vitro and in vivo, adoptive transfer of cruzipain-specific Th1 cells alone did not protect BALB/c histocompatible mice, indicating that additional immune mechanisms are important for cruzipain-specific immunity. To study whether cruzipain could induce mucosal immune responses relevant for vaccine development, we prepared recombinant attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccines expressing cruzipain. BALB/c mice immunized with salmonella expressing cruzipain were significantly protected against T. cruzi mucosal infection. Overall, these data indicate that cruzipain is an important T. cruzi vaccine candidate and that protective T. cruzi vaccines will need to induce more than CD4+ Th1 cells alone.

Trypanosoma cruzi, the agent of Chagas' disease, is an important pathogen in Latin America, with an estimated 16 to 18 million people infected with the parasite (61). About one-third of these individuals will develop clinically significant chagasic pathology, the majority with cardiac manifestations. Although an autoimmune etiology has been suggested for Chagas' disease (24), multiple recent studies have demonstrated that in both T. cruzi-infected mice and humans, tissue pathology is correlated with the persistence of parasite infection (7, 9, 23, 29, 46, 60). These data, along with the lack of highly efficacious treatments available for Chagas' disease, provide a strong rationale for efforts to develop a vaccine protective against T. cruzi infection.

Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are involved in T. cruzi systemic immunity, since mice lacking functional cells of either type (by genomic knockout [47, 57, 58] or by in vivo antibody depletion [3, 56, 59]) have increased susceptibility to T. cruzi. In mice, it has been shown that CD4+ Th1 responses (characterized by gamma interferon [IFN-γ] production) are associated with T. cruzi resistance, while CD4+ Th2 responses (characterized by interleukin 4 [IL-4] production) are associated with T. cruzi susceptibility (20, 22, 28). Studies of humans with chagasic cardiomyopathy also suggest that T cells producing IFN-γ and IL-4 correlate with resistance and susceptibility, respectively, to cardiac disease (46). Furthermore, we have shown previously that vaccines inducing T. cruzi-specific Th1 responses can protect mice against virulent T. cruzi challenges (21). In addition to the induction of protective effector functions, such as microbicidal NO (38), CD4+ Th1 cells probably serve as important helper cells enhancing both CD8+-T-cell and antibody responses. As with other intracellular infections, CD8+ T cells are important for recognition of parasite antigens presented by major histocompatibility complex class I molecules on the surfaces of infected cells. Lytic serum antibodies can be protective against the extracellular life stages of T. cruzi (26, 27, 31, 52), and secretory immunoglobulin A responses may be relevant for protection against mucosal transmission from the reduviid vector (18).

One candidate protein for vaccine development is cruzipain, the cysteinyl proteinase of T. cruzi. Cruzipain is a 57-kDa protein highly homologous with other members of the papain superfamily of proteases (12, 14, 40), except for its C-terminal extension, which is unique to trypanosomes (5). Although the level of cruzipain expression varies, it is produced by all life stages of the parasite (11, 49) and could be a target for immunity throughout all phases of T. cruzi infection. Surface localization of cruzipain has been reported (42, 49), making cruzipain a potential target for lytic antibodies effective against intact extracellular parasites. Although different isoforms are found in the parasite genome (30), highly homologous forms of cruzipain are expressed in different strains of T. cruzi (10), indicating that cruzipain-specific immunity could be reactive with parasites from widely disparate endemic regions. Furthermore, specific inhibitors of cysteinyl proteinases and cruzipain-specific antibodies have been shown to inhibit T. cruzi intracellular replication in vitro (36, 54).

Cruzipain has been shown to be antigenic in T. cruzi-infected persons, a fact that is relevant for the development of a vaccine useful in humans. The majority of Chagas' disease patients have serum antibodies reactive with cruzipain (32, 33, 49). In addition, cruzipain-specific T-cell lines generated from T. cruzi-infected individuals have been shown to produce IFN-γ but not IL-4 (4), indicating that cruzipain induces human Th1 cell responses.

In this report, we demonstrate that cruzipain-specific CD4+ Th1 cells can induce macrophages to produce NO and inhibit parasite replication in vitro. We also demonstrate in vivo that cruzipain-specific immunity induced by recombinant cruzipain vaccines can protect mice against virulent T. cruzi mucosal and systemic challenges.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms used.

The mice used in these studies were 6- to 10-week-old BALB/c mice. The Tulahuén strain of T. cruzi was used in the experiments. Culture-derived metacyclic trypomastigotes (CMT) were generated in Grace's medium as previously described (20). Blood form trypomastigotes (BFT) were obtained from BALB/c or SCID mice infected 2 to 3 weeks previously. Insect-derived metacyclic trypomastigotes (IMT) were obtained from T. cruzi-infected Dipetalogaster maximus reduviid insects as previously described (18).

Reagents used.

The 212BH6 monoclonal antibody (MAb) specific for cruzipain (39) was provided by Julio Scharfstein (Universidade Rio de Janiero, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). To prepare total T. cruzi lysate, CMT were washed three times with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), freeze-thawed four times, and ultracentrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h, and the supernatant was clarified by passage through 0.45-μm-pore-size filters.

Purification of recombinant cruzipain.

The DNA fragment encoding the mature cruzipain enzyme (amino acids 1 to 345) was amplified by PCR from a cDNA library prepared from Tulahuén trypomastigote mRNA with cruzipain-specific primers (GCGCCATGGCGCCCGCGGCAGTGGATTGG [5′ end of the coding sequence with an NcoI site incorporated] and GCGAAGCTTCCCTCAGAGACGGCGATGACGGCT [3′ region at the stop codon of cruzipain with a HindIII site incorporated]). NcoI- and HindIII-digested pSCREEN plasmid (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) and the cruzipain-specific PCR product were ligated and used for transformation of Escherichia coli following standard techniques (48). The cruzipain cDNA present in this recombinant plasmid was sequenced by the dideoxy chain termination method and found to be >95% identical to the sequence published by Eakin et al. (14). This recombinant pSCREEN-cruzipain plasmid expresses a fusion protein with the phage10 protein (T7 bacteriophage gene 10 protein) encoded by the vector at the N terminus linked to the full-length mature cruzipain sequence (amino acids 1 to 345) at the C terminus. The phage10 control and recombinant phage10/cruzipain proteins were purified from lysates of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside-induced E. coli BL21(pLysS) transformed with the empty pSCREEN and pSCREEN-cruzipain plasmids, respectively, by His tag affinity chromatography. Inclusion bodies containing these proteins were pelleted by centrifugation and washed three times with 50 mM Tris-50 mM NaCl-1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0. The washed inclusion bodies were suspended in 50 mM Tris-50 mM NaCl-1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, with 8 M urea and stirred for 4 h at room temperature. After centrifugation for 15 min at 12,000 × g, the supernatants were diluted 10-fold into 20 mM Tris-300 mM NaCl, pH 10.7, and stirred for 1 h at room temperature. After the pH was adjusted to 8.0, the solutions were stirred for one more hour. Solubilized protein was filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size filters and purified over Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose columns (Qiagen, San Diego, Calif.) as described by the manufacturer. Endotoxin was removed with Triton X-114 as described previously (2). Residual Triton X-114 was removed with SM-2 beads (Bio-Rad). The endotoxin levels in the final purified proteins were <100 endotoxin units/mg, determined using Limulus amebocyte lysate (Associates of Cape Cod, Woods Hole, Mass.). Protein levels were determined using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). Both phage10 control and phage10/cruzipain final protein preparations were >95% pure as assessed by Coomassie-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Western blots were probed with the 212BH6 cruzipain-specific MAb to confirm the presence of cruzipain epitopes within the phage10/cruzipain fusion protein as previously described (19).

Generation of T-cell lines.

Cruzipain-specific T-cell lines were derived from infected BALB/c mice. To bias for Th1 responses during infection, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 μg of IL-12 daily for 18 days. On days 2, 9, and 19, these mice were also injected intraperitoneally with 1 mg of the anti-IL-4 neutralizing MAb 11B11. On day 4, the mice were infected with 20,000 IMT subcutaneously. Two months after infection, the spleens from these mice were harvested, and CD4+ T cells were purified by positive magnetic selection in Mini-MACS columns (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, Calif.). The CD4+ T cells were stimulated with 2 μg of recombinant cruzipain/ml in the presence of syngeneic irradiated spleen cells as antigen-presenting cells. One week later, the cells were expanded in the presence of 10 U of IL-2/ml. This alternating schedule of antigen stimulation and IL-2 expansion was repeated biweekly.

To generate negative control ovalbumin-specific Th1 cell lines, CD4+ T cells were purified from the spleen of a female D10.11 TCR transgenic mouse (provided by Lynn Dustin). CD4+ T cells were stimulated with syngeneic irradiated spleen cells, 100 μg of ovalbumin/ml, and 10 U of IL-12/ml to bias for Th1 responses. These cultures were then maintained by an alternating schedule of antigen stimulation and IL-2 expansion repeated biweekly. IL-12 was added during the second and third antigen stimulations to further enhance the generation of ovalbumin-specific Th1 cells.

For testing antigen specificity and cytokine profiles, T cells were studied 2 weeks after the last antigenic stimulation and 1 week after the last IL-2 expansion step. T cells (104/well) were stimulated in 96-well plates with syngeneic spleen cells and titrations of phage10 control or recombinant cruzipain proteins (0 to 0.4 μg/ml). After 48 h at 37°C, the supernatants were harvested for cytokine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) studies. Both T-cell lines produced IFN-γ, but not IL-4, in an antigen-specific, major histocompatibility complex-restricted fashion.

In vitro protection assays.

Female BALB/c mice were given 100 μg of concanavalin A intraperitoneally to activate peritoneal macrophages. Four days later, the peritoneal exudate macrophages (PEM) were harvested from these mice and cultured in eight-well tissue culture slide chambers (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, Ill.) at 1.25 × 106 cells/well in 500 μl of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium plus 10% fetal calf serum. The PEM were allowed to adhere for at least 2 h at 37°C, washed twice with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium plus 2% fetal calf serum, and infected with 6.25 × 106 CMT (a multiplicity of infection of 5). These cultures were incubated overnight at 37°C and then washed three times to remove extracellular parasites. Cruzipain- or ovalbumin-specific T cells were added at 5 × 104 cells/well. Forty-eight hours after the addition of T cells, the supernatants were collected from these cocultures. Adherent PEM were then fixed with 1% formalin and Giemsa stained (Diff Quik; Dade International Inc., Miami, Fla.). The number of infected cells per 200 total cells and the average number of intracellular amastigotes (AMA) per infected cell were determined by microscopic examination of the stained slides. IFN-γ and IL-4 levels in the culture supernatants were measured by ELISA as described below. NO in the supernatants was measured by a modified Greiss reaction (17, 38). Controls included uninfected wells to confirm the antigen specificity of cytokine production and wells to which T cells were not added to determine the level of infection in the absence of any immune response. Percent inhibition of infected cells or intracellular AMA/infected cell was defined as [1 − (value with T cells/value without T cells)] × 100.

Induction of cruzipain-specific Th1 responses.

In order to induce cruzipain-specific immunity highly polarized toward Th1 responses in vivo, immunizations were given with IL-12 and the neutralizing anti-IL-4 MAb 11B11 as previously described (21). Three vaccinations with phage10 or phage10/cruzipain were given at 2-week intervals. The first and second immunizations were given with IL-12 and 11B11. The third immunization included antigen alone. IL-12 (1 μg) was given either subcutaneously or intraperitoneally the day before, the day of, and the day after antigen administration. The 11B11 MAb was given intraperitoneally the day before and 2 days after antigen administration. The phage10 and phage10/cruzipain antigens were given subcutaneously (25 to 50 μg/dose). Four weeks after the third immunization, representative animals received a booster dose of parasite lysate, and spleen cells were harvested 3 days later for in vitro immune studies. The remaining immunized and control mice were challenged 4 to 6 weeks after the third vaccination with 5,000 to 20,000 T. cruzi BFT subcutaneously.

Proliferation assays.

Draining lymph node cells (LNC) from immunized mice were incubated in 96-well tissue culture plates (4 × 105 cells/well) at 37°C and 5% CO2 in the presence of medium, recombinant protein, or 10 μg of T. cruzi lysate/ml for 5 days. After the supernatants were harvested on the fifth day, fresh medium containing 0.5 μCi of [3H]thymidine (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) was added to each well. The cells were incubated another 4 to 6 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 and harvested with a semiautomatic cell harvester (Skatron, Sterling, Va.), and incorporated radioactivity was counted in a Taurus automatic liquid scintillation counter (ICN Biomedical, Huntsville, Ala.). The stimulation index was defined as the disintegrations per minute after antigen stimulation divided by the disintegrations per minute after incubation with medium alone.

In vitro stimulations and cytokine assays with freshly harvested lymphocytes.

After draining LNC were harvested from immunized mice, CD4+ T cells were purified by magnetic selection using Mini-MACS (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer's instructions. CD4+ T cells (1 × 105 to 4 × 105/ml) were incubated in 24-well tissue culture plates in the presence of medium or antigen and irradiated syngeneic spleen cells (2 × 106/well). The supernatants were studied after incubation at 37°C for 4 days. IFN-γ and IL-4 cytokine levels in the culture supernatants were measured by ELISA as previously described (20).

Construction of a recombinant attenuated Salmonella vaccine expressing cruzipain used for mucosal immunization and challenge experiments.

We used the χ4550 attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strain that lacks functional cya, crp, and asd gene products to produce a recombinant salmonella vaccine expressing cruzipain (41). This salmonella vector was transformed with the empty asd+ complementation plasmid pYA3341 or with a recombinant pYA3341 plasmid encoding cruzipain under the control of a trc promoter. This multicopy plasmid expresses less asd functional protein than previous asd+ vectors, minimizing the selective disadvantage of plasmid maintenance and allowing for enhanced immunization with expressed recombinant antigens (25). The phage10/cruzipain DNA fragment (encoding amino acids 1 to 345 of cruzipain) was amplified by PCR from the pSCREEN-cruzipain plasmid and subcloned into the pYA3341 plasmid using NcoI 5′ and HindIII 3′ insertion sites. Cruzipain protein expression in recombinant Salmonella transformed with this plasmid was confirmed by Western blotting. Mice were vaccinated four times intranasally with control and cruzipain-expressing salmonella cells. The mice were lightly anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine given intraperitoneally, and salmonella vaccines were administered in 10-μl volumes of PBS. A total of 2 × 106 CFU of salmonella was given for primary vaccinations, and 2 × 107 CFU of salmonella was given for booster vaccinations. The second vaccinations were given 4 weeks after the priming doses, and the three booster vaccinations were given at 2-week intervals. One month after the final vaccinations, the mice were challenged orally with 2,000 T. cruzi IMT. Fourteen days after challenge, gastric tissues (where initial T. cruzi mucosal invasion occurs) were studied for levels of T. cruzi DNA by real-time PCR (described below), and draining gastric LNC were examined for viable T. cruzi parasites by a limiting-dilution quantitative-culture technique as previously described (18).

Real-time PCR detection of T. cruzi in mucosal tissues.

Mouse stomachs were removed by cutting the esophageal and pyloric attachments. These organs were opened along the greater curvature and flushed with sterile PBS. Gastric tissue DNA samples were purified using a commercially available QIAamp kit (Qiagen), and the total DNA concentrations were adjusted to 40 ng/μl. Primers (5′ AACCACCACGACAACCACAA 3′ and 5′ TGCAGGACATCTGCACAAAGTA 3′) predicted to specifically amplify a 65-bp fragment of cruzipain were chosen using Primer Express version 1.5a software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Real-time PCRs were set up using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), 900 nM (each) primer, and 200 ng of sample DNA. A standard curve was generated using positive control DNA harvested from a known concentration of T. cruzi epimastigotes grown in pure culture. These reactions were run in an ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems) using the following conditions: 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Analysis was performed using Sequence Detection Systems version 1.7a software (Applied Biosystems).

RESULTS

Purification of recombinant cruzipain.

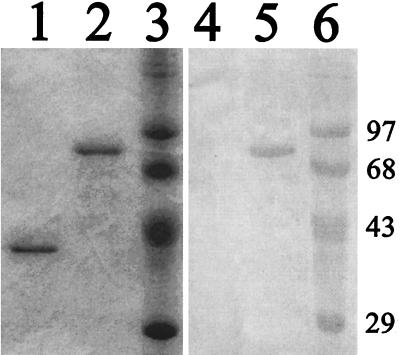

Affinity chromatography on His×Bind resin led to the purification of proteins with sizes of 33 and 84 kDa, respectively, from the pSCREEN and pSCREEN-cruzipain plasmid-transformed E. coli (Fig. 1.). Although the predicted mass of the cruzipain fusion protein is 74 kDa, it has been reported previously that both the recombinant and native cruzipain proteins migrate with masses larger than those predicted by their amino acid sequences (34). Recombinant cruzipain, but not the phage10 control protein, was detected in Western blots using the 212BH6 cruzipain-specific MAb as a probe (Fig. 1.), confirming the identity of the purified product as cruzipain.

FIG. 1.

Purification of recombinant cruzipain. Equivalent amounts of the phage10 control protein (lanes 1 and 4) and cruzipain (lanes 2 and 5) purified from bacterial lysates were separated on 10% polyacrylamide gels next to prestained molecular mass standards (lanes 3 and 6). Lanes 1 to 3 show Coomassie staining of separated proteins. Lanes 4 to 6 show proteins blotted to nitrocellulose and probed with the 212BH6 MAb specific for cruzipain. Molecular masses in kilodaltons are indicated at the right.

Cruzipain-specific Th1 cells protect against parasite infection in vitro.

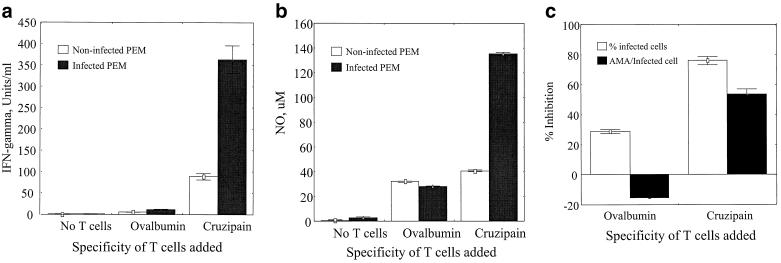

To test the hypothesis that cruzipain-specific Th1 cells can mediate protective T. cruzi immunity, we generated cruzipain-specific Th1 cell lines as described in Materials and Methods. The protection provided by these cell lines was first tested in an in vitro model. Cruzipain-specific Th1 cells were incubated with PEM that were either infected with T. cruzi or uninfected, and cytokine and NO responses were measured as described in Materials and Methods. Th1 cells specific for ovalbumin were studied in parallel experiments to control for nonspecific effects. The cruzipain- and ovalbumin-specific T-cell lines produced IFN-γ but not IL-4 in response to soluble cruzipain or ovalbumin, respectively (data not shown), confirming that they were Th1-like T-cell lines. In the absence of T cells, culture supernatants from both infected and uninfected PEM had no detectable levels of IFN-γ (Fig. 2a). Ovalbumin-specific T cells produced low levels of IFN-γ that were not different in infected and uninfected PEM cultures. However, the cruzipain-specific Th1 cells produced 344 U of IFN-γ/ml when incubated with infected PEM, a 3.9-fold increase compared with the response after incubation with uninfected PEM (Fig. 2a). These results demonstrate that cruzipain-specific Th1 cells can respond to cruzipain in the context of intracellular T. cruzi infection. The levels of NO in these cultures were measured as well (Fig. 2b). PEM produced only very low NO levels in the absence of T cells, and addition of the ovalbumin-specific control cells led to only minimal increases in NO production that were not different in infected and uninfected cultures. Cruzipain-specific Th1 cells did not induce uninfected PEM to produce NO above background levels seen with ovalbumin-specific T cells. However, these cruzipain-specific cells did induce a >3-fold increase in NO production from infected PEM. The increased IFN-γ and NO responses present in cultures of cruzipain-specific Th1 cells and infected PEM were associated with inhibition of T. cruzi intracellular replication (Fig. 2c). Infected macrophages cultured with ovalbumin-specific Th1 cells had similar percentages of infected cells and increased numbers of AMA per infected cell detectable after 48 h compared with infected macrophages cultured without T cells. In contrast, the cruzipain-specific Th1 cells inhibited the proportion of infected cells by 76% and reduced by 53% the average number of AMA per infected cell. Parallel cultures were set up in 24-well plates and incubated at 37°C for up to 1 week. In the absence of T cells, or in the presence of ovalbumin-specific control T cells that did not inhibit T. cruzi growth, trypomastigotes were easily detected in the supernatants by 72 h. However, in the cultures incubated with cruzipain-specific Th1 cells, trypomastigotes were never detected (data not shown). These data indicate that cruzipain-specific Th1 cells are protective against intracellular T. cruzi replication in vitro.

FIG. 2.

Cruzipain-specific, CD4+ Th1 cells induce NO and protect against intracellular T. cruzi replication in murine macrophages. PEM were cultured in tissue culture slide chambers alone or infected with T. cruzi trypomastigotes. Cruzipain-specific T cells, ovalbumin-specific control T cells, or no T cells were added, and the cultures were incubated for 48 h prior to the supernatants being harvested for measurements of IFN-γ (a) and NO (b) production. The percentage of T. cruzi-infected macrophages and the average number of AMA per infected cell were counted microscopically (c). The effects of added T cells are expressed as the percent inhibition of T. cruzi infection compared with macrophages in the absence of T cells. Shown are the means ± standard errors from duplicate PEM cultures. Similar results were seen in multiple experiments.

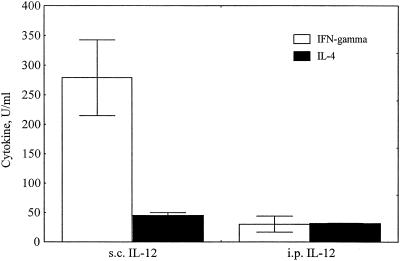

IL-12 more effectively biases for Th1-like responses when given by the same route as antigen.

To determine the most effective method for using IL-12 to induce Th1-polarized immune responses, different routes for the administration of IL-12 were compared. Two groups of mice were immunized subcutaneously with whole T. cruzi lysate three times at 2-week intervals. In each case, the first two immunizations were given with IL-12 on the day before, the day of, and the day after antigen administration, and the 11B11 IL-4-neutralizing MAb on the day before and 2 days after antigen administration. The 11B11 MAb was given intraperitoneally to both groups. The route of IL-12 administration was the only difference between these immunization groups. One group was given IL-12 intraperitoneally, and the other was given IL-12 subcutaneously. One month after the last immunization, the mice were given a booster dose of parasite lysate alone. Three days after the boost, spleen cells from these mice were harvested and stimulated in vitro with parasite lysate. IFN-γ and IL-4 production were measured as described in Materials and Methods. IL-12 given by the same route as antigen (subcutaneously) induced more-potent IFN-γ responses that were predominantly polarized to a Th1 type of response, based on the 10-fold up regulation of IFN-γ production with limited IL-4 production (Fig. 3.).

FIG. 3.

IL-12 administered by the same route as antigen induces optimal Th1-polarized responses. Two groups of mice were immunized three times with parasite lysate. With the first two immunizations, IL-12 was given the day before, the day of, and the day after antigen administration, and IL-4-neutralizing 11B11 was given the day before and 2 days after antigen administration. The third immunization included antigen alone. Antigen was given subcutaneously (s.c.), and 11B11 was given intraperitoneally (i.p.). Group A was given IL-12 subcutaneously, and group B was given IL-12 intraperitoneally. Three days after the last immunization, LNC were harvested and stimulated in vitro with or without parasite lysate for 3 days. The supernatants were harvested and assayed for IFN-γ and IL-4 production by ELISA. Shown are the means ± standard errors. The background results from cultures incubated without parasite lysate were subtracted from the results obtained in matching cultures incubated with parasite lysate.

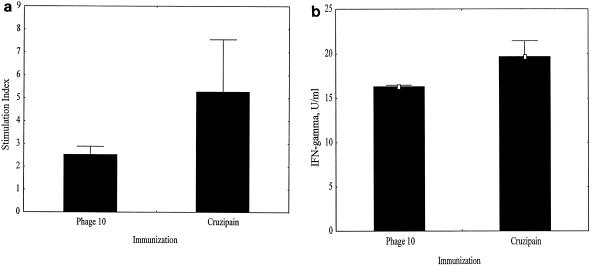

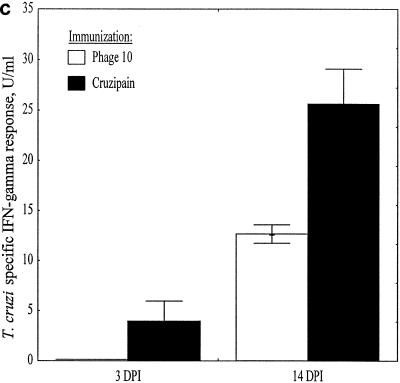

Immunization with cruzipain plus IL-12 and 11B11 induces antigen-specific Th1 cells.

Groups of mice were immunized with either phage10 control or phage10/cruzipain recombinant protein as described in Materials and Methods using IL-12 and 11B11 to bias for Th1 responses. Untreated control groups were also included. One month after the last immunization, two mice/group were given a booster dose of antigen. Draining LNC were harvested from these animals 3 days later. The CD4+ T cells were purified and stimulated in the presence of syngeneic, irradiated spleen cells for 3 days with or without cruzipain to ensure that the immunization induced Th1-like antigen-specific responses. Proliferative (Fig. 4a), IFN-γ (Fig. 4b), IL-4 (not shown), and IL-10 (not shown) responses were measured. Immunization with cruzipain induced an antigen-specific proliferative response, with fivefold-higher incorporation of thymidine after stimulation with cruzipain than after incubation with medium alone, indicating that the immunization was successful. These cells also made increased amounts of IFN-γ after stimulation with cruzipain compared with control cultures. However, there was no change in IL-4 or IL-10 production, with only low levels (<5 U of IL-4/ml and <2 U of IL-10/ml) of these cytokines made after stimulation with antigen. IFN-γ production without detectable IL-4 or IL-10 production demonstrates that the immunization protocol successfully induced Th1 but not Th2 responses. The response of lymphocytes harvested from phage10-immunized mice to recombinant cruzipain was expected, since the phage10 protein is present as a fusion partner expressed with the recombinant cruzipain. Therefore, the proliferative and IFN-γ responses induced in these mice confirm that the control group was also immunized effectively and developed antigen-specific Th1-like responses.

FIG. 4.

Immunization with cruzipain induces potent Th1 memory responses. Draining LNC were harvested from mice after immunization with phage10 control protein or cruzipain plus IL-12 and the IL-4 neutralizing MAb 11B11. CD4+ T cells were purified and cultured in vitro in the presence or absence of cruzipain for 3 days. (a) Proliferation was measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation. The results are shown as stimulation indices. (b) IFN-γ production was measured by ELISA using the supernatants collected after 3 days of stimulation. The results are shown after background IFN-γ levels present in medium-rested culture supernatants were subtracted. Antigen-specific responses are expected after immunization with phage10 protein because the recombinant cruzipain used for in vitro stimulation contains the phage10 protein as an N-terminal fusion partner. The error bars indicate standard errors.

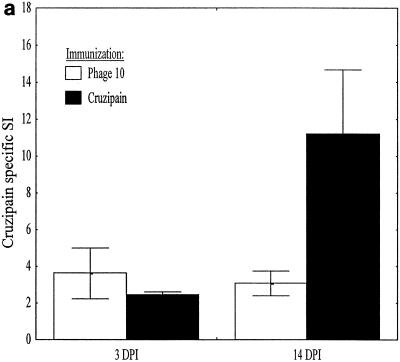

Cruzipain-immunized mice respond to infection with enhanced parasite-reactive IFN-γ responses.

Mice were immunized with phage10 control or phage10/cruzipain protein, plus IL-12 and 11B11 as described above, and then challenged with T. cruzi BFT. Three and 14 days after infection LNC were harvested from two mice per group. The CD4+ T cells were purified and stimulated in vitro with either recombinant cruzipain or parasite lysate. After 3 days, culture supernatants were harvested for cytokine studies and lymphoproliferative responses were measured by thymidine incorporation. Three days after infection, the phage10- and phage10/cruzipain-immunized mice had similar proliferative responses inducible with recombinant cruzipain (Fig. 5a). Again, since the phage10 protein is included in the recombinant cruzipain fusion protein, this result was expected. However, by 14 days after infection, a dramatic increase in this proliferative response was detected in CD4+ lymphocytes harvested from the cruzipain-immunized mice but not in CD4+ lymphocytes harvested from phage10-immunized mice. IFN-γ responses after in vitro stimulation with cruzipain (Fig. 5b) and parasite lysate (Fig. 5c) were also measured. Three days after infection, CD4+ T cells from cruzipain-immunized mice produced fivefold-higher levels of IFN-γ after in vitro stimulation with cruzipain compared with CD4+ T cells from phage10-immunized mice, despite the fact that similar IFN-γ responses were detected in both groups prior to infection (Fig. 4b). The increased IFN-γ responses detected in cruzipain-immunized mice persisted for 14 days after infection. The CD4+ T cells harvested from cruzipain-immunized mice also produced increased IFN-γ responses after stimulation with parasite lysate 3 days postchallenge (Fig. 5c). No such response was seen in the control CD4+ T cells. Increased parasite lysate-specific IFN-γ responses persisted in CD4+ T cells from cruzipain-immunized mice 2 weeks after the T. cruzi challenge. There were no detectable differences between the two groups in IL-4 or IL-10 production. In most cases, the levels of both of these cytokines were below the limits of detection for the assays.

FIG. 5.

Mice were immunized with cruzipain plus IL-12 and 11B11 and challenged with virulent T. cruzi BFT 1 month later. Three and 14 days postinfection, draining LNC were harvested and CD4+ T cells were purified. The CD4+ T cells were cultured in vitro for 3 days with medium, cruzipain, or whole T. cruzi lysate. (a) Proliferative responses to cruzipain were measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation and are shown as stimulation indices (SI). IFN-γ responses to cruzipain (b) and parasite lysate (c) were measured by ELISA. The results are shown after background levels of IFN-γ present in supernatants from cultures incubated with medium alone were subtracted. The error bars indicate standard errors. DPI, days postinfection.

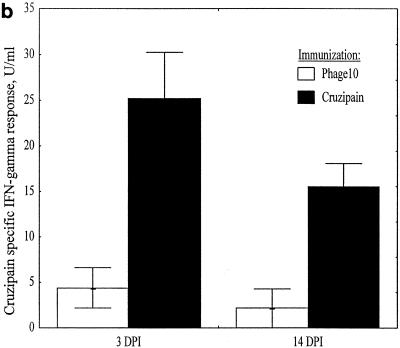

The immune responses induced by immunization with cruzipain are protective against lethal parasite challenge.

Mice were immunized as described in Materials and Methods. Four weeks after the last immunization, these mice were challenged subcutaneously with 5,000 T. cruzi BFT. Beginning 2 weeks postchallenge and continuing until 4 weeks post challenge, individual parasitemia levels were assessed (Fig. 6a). As early as 15 days after immunization, the parasitemias detected in the cruzipain-immunized group were significantly lower than those in the phage10-immunized and unimmunized groups (P < 0.05 by the Mann-Whitney U test). Significantly reduced parasitemias persisted in the cruzipain-immunized group throughout the remainder of the first month postchallenge. Although there were no differences among the groups in the time it took to reach peak parasitemia, there were 5.3- and 8.7-fold decreases in peak parasitemia levels in the cruzipain-immunized animals compared with the phage10-immunized and unimmunized animals, respectively. At no time point was there a significant difference in parasitemia levels between the two control groups.

FIG. 6.

Immunization with cruzipain and Th1-biasing reagents induces protective immunity against T. cruzi challenge. Mice were immunized with cruzipain plus IL-12 and the IL-4-neutralizing 11B11 MAb as described in the text. One month after the last immunization, the mice were challenged with virulent T. cruzi BFT. (a) Parasitemias measured by microscopic examination of blood samples postchallenge. For the unimmunized, phage10, and cruzipain groups, n = 5, 9, and 8, respectively. (b) Survival data postchallenge in a second immunization experiment with a more virulent T. cruzi challenge (n = 5/group). Statistically significant differences are denoted by asterisks: P < 0.05 comparing the cruzipain-immunized group with the unimmunized control group, as determined by the Mann-Whitney U test (a) or by the two-tailed Fisher's exact test (b). There were no significant differences detected in comparisons between the control groups. The error bars indicate standard errors.

In a second experiment, mice were given a more virulent T. cruzi challenge, and cruzipain immunization resulted in both reduced parasitemias and significantly reduced mortality compared with control mice (Fig. 6b). While all of the unimmunized mice died within 1 month of infection, 80% of the cruzipain-immunized mice survived for >10 weeks postchallenge (P < 0.05 by Fisher's exact test). Mice given IL-12 and anti-IL-4 alone were not protected against T. cruzi challenge (data not shown).

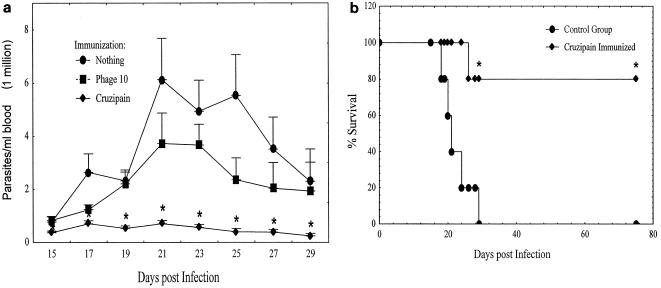

Mucosal vaccination with recombinant salmonella expressing cruzipain protects against T. cruzi mucosal infection.

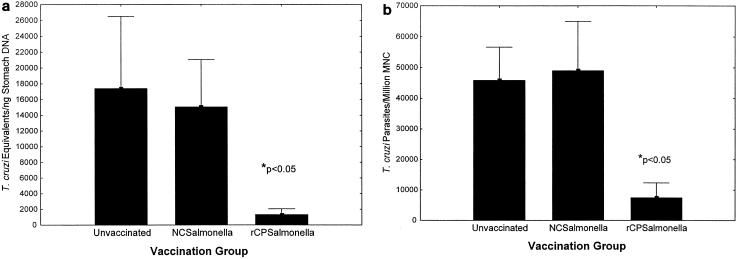

Recombinant attenuated S. enterica serovar Typhimurium expressing cruzipain was prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Mice were vaccinated four times intranasally. A total of 2 × 106 CFU of salmonella was given for primary vaccination, and 2 × 107 CFU of salmonella was given for three booster vaccinations. The second vaccination was given 4 weeks after the first dose, and the three booster vaccinations were given at 2-week intervals. One month after the last vaccination, the mice were challenged orally with T. cruzi IMT. Fourteen days after challenge, gastric tissues (at the point of initial T. cruzi mucosal invasion [18]) were studied for levels of T. cruzi DNA by real-time PCR (Fig. 7a), and draining gastric LNC were examined for viable T. cruzi parasites by a limiting-dilution quantitative-culture technique (Fig. 7b). Highly significant decreases in recoverable T. cruzi DNA and viable parasites were detected in mice vaccinated with recombinant salmonella expressing cruzipain compared with unvaccinated and vaccinated control mice (P < 0.05 by Student's t test). These results were reproducible in three independent experiments. Therefore, cruzipain can induce antigen-specific mucosal protection against T. cruzi infection. In addition, in preliminary experiments intranasal vaccination with salmonella expressing cruzipain was protective against subcutaneous BFT challenges (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

A recombinant salmonella vaccine expressing cruzipain induces T. cruzi mucosal protection. Mice were vaccinated four times intranasally with recombinant salmonella expressing cruzipain (rCPSalmonella) or control salmonella transformed with the vector alone (NCSalmonella); 2 × 106 CFU of salmonella were given for primary vaccination, and 2 × 107 CFU of salmonella were given for three booster vaccinations. The second vaccination was given 4 weeks after the first dose, and the three booster vaccinations were given at 2-week intervals. One month after the last vaccination, the mice were challenged orally with T. cruzi IMT. Fourteen days after challenge, gastric tissues (where initial T. cruzi mucosal invasion occurs) were studied for levels of T. cruzi DNA by real-time PCR (a), and draining gastric LNC were examined for viable T. cruzi parasites by a limiting-dilution quantitative-culture technique (b). ∗, P < 0.05 comparing the mice given salmonella expressing cruzipain with control mice by Student's t test.

DISCUSSION

Because T. cruzi replicates as an intracellular pathogen in mammalian hosts, we first investigated the feasibility of a cruzipain-based vaccine by determining whether cruzipain-specific immune responses could recognize and inhibit intracellular T. cruzi parasites. This was assessed using an in vitro model of infection. CD4+ Th1 cells have been shown to be protective against T. cruzi in vivo (20, 37, 43, 44), and they can be easily produced in vitro by recurrent stimulation with soluble proteins. Therefore, we generated stable Th1 cell lines from BALB/c mice that were reactive with our purified recombinant cruzipain antigen. We generated these Th1 cells with lymphocytes harvested from infected mice to maximize the chances that the T cells would be specific for cruzipain epitopes presented by T. cruzi-infected host cells. Indeed, our cruzipain-specific Th1 cells responded to infected macrophage cultures in vitro with the production of IFN-γ, leading to the induction of NO production by infected macrophages and potent inhibition of intracellular parasite replication (Fig. 2.). These results demonstrated that cruzipain-specific Th1 cells are relevant for the control of T. cruzi infection, supporting further study of cruzipain as a vaccine candidate for Chagas' disease.

After demonstrating that cruzipain-specific Th1 cells could be protective against T. cruzi infection in vitro, we conducted immunization experiments to determine whether cruzipain-specific immunity could protect mice in vivo. Mice were immunized with combinations of recombinant cruzipain, recombinant IL-12, and anti-IL-4 neutralizing MAb to induce highly polarized cruzipain-specific Th1 cell responses (Fig. 3 to 6). The optimal immunization schedule included three doses of cruzipain given subcutaneously 2 weeks apart. With the first two doses, IL-12 was given subcutaneously the day before, the day of, and the day after antigen administration. The IL-4-neutralizing antibody was administered intraperitoneally the day before and 2 days after injection of antigen. Measurements of antigen-specific immune responses present after this vaccination protocol confirmed that cruzipain-specific memory T cells with a highly polarized Th1 cytokine profile had been induced (Fig. 4.). Furthermore, the vaccine-induced priming of these cruzipain-specific memory Th1 cells led to the development of a more rapid and potent overall Th1 response during infectious T. cruzi challenge (Fig. 5.). However, the most important test of a vaccine is its ability to protect against disease. Mice were immunized with our cruzipain Th1 bias protocol and challenged with a lethal dose of T. cruzi BFT. Immunization with cruzipain led to significantly decreased parasitemias compared with phage10 control-immunized and unimmunized mice (Fig. 6.). The difference in parasitemia was apparent as early as 15 days after infection and persisted for 2 weeks, with up to eightfold decreases in parasitemia. Cruzipain-immunized mice were also protected against death, with 80% of these mice surviving the parasite challenge. These results clearly indicate that cruzipain-specific immunity can protect against T. cruzi challenges in vivo.

Our data suggest that cruzipain-specific Th1 cells are likely to be important for vaccine-induced protection against T. cruzi infection. However, we have not clearly identified the mechanism(s) responsible for the protective immunity induced by our cruzipain immunization protocol. It is possible that an early production of potent IFN-γ responses by cruzipain-specific memory Th1 cells during acute T. cruzi infection could enhance Th1 cell and inhibit Th2 cell responses specific for other parasite antigens expressed by infected cells (8, 51). By this mechanism of secondary influence, induction of cruzipain-specific Th1 cells could increase the levels of T. cruzi resistance not only through cruzipain-specific immune responses but also by shifting the overall pattern of T helper cell development toward a Th1 profile.

To investigate the possibility that cruzipain-specific Th1 cells alone could enhance T. cruzi resistance, we performed adoptive-transfer experiments with our stable cruzipain-specific Th1 cell lines (data not shown). In multiple experiments, we injected 5 to 20 million purified cruzipain-specific Th1 cells into BALB/c histocompatible mice, but these mice were not protected against virulent challenges with T. cruzi BFT. In fact, mice given our purified cruzipain-specific Th1 cells tended to develop slightly higher parasitemias and succumbed a day or two before control mice. We observed a similar absence of protection when we adoptively transferred Th1 cells generated by recurrent stimulation with whole T. cruzi lysate. These results surprised us, because previous investigators had been able to adoptively transfer protection against virulent T. cruzi challenges with parasite-specific Th1 cell lines and clones given to naive immunocompetent mice (37, 43, 44). However, the previous protective Th1 transfer experiments had been done in B6 mice that are relatively resistant to T. cruzi infection, and we had been working with more susceptible BALB/c mice. In preliminary experiments, we have seen that during the first week of T. cruzi infection, lymphocytes harvested from BALB/c mice with adoptively transferred parasite-specific Th1 cells develop 70- to 80-fold increases in IL-10 responses compared with infected control BALB/c mice (unpublished data). Therefore, we hypothesize that in BALB/c mice with adoptively transferred T. cruzi-specific Th1 cells, a hyperresponsive autoregulatory IL-10 response inactivates macrophages, preventing NO production and leading to uncontrolled intracellular parasite replication. We are currently testing this hypothesis.

Other possible mechanisms for the protective immunity induced by our cruzipain Th1 bias protocol could involve lymphocyte subsets other than CD4+ T lymphocytes. IL-12 is known to enhance the development of CD8+ cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte responses (35, 55) and, by induction of Th1 cells, leads to increased immunoglobulin G2a isotype-specific antibody responses (1). CD8+-cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte responses have been shown to be critical for resistance during primary T. cruzi infection (15, 56, 58, 62), and antibodies inhibiting the cysteinyl proteinase activity of cruzipain could modify T. cruzi virulence (36, 54). Therefore, either of these immune responses could be important for the protection mediated by our cruzipain Th1 bias immunization protocol. Optimal induction of protective immunity against T. cruzi may require vaccines combining CD4+-T-cell, CD8+-T-cell, and B-cell epitopes.

Regardless of the mechanism(s) responsible for cruzipain-specific protective immunity achieved in our present work, these data provide the first evidence that cruzipain-based vaccines can protect against T. cruzi challenge. In addition, our studies with recombinant salmonella expressing cruzipain provide the first demonstration that a T. cruzi vaccine can induce protective mucosal immunity (Fig. 7). Several different strategies could be used to enhance cruzipain-specific protection. The use of other adjuvants or live vaccine vectors may result in the induction of more protective mucosal and systemic T. cruzi immunity. Prime-boost combinations of subunit and live vaccines designed to optimize CD8+-T-cell responses may also increase the level of cruzipain-specific protective immunity (50). In addition, vaccines expressing parasite epitopes derived from multiple different T. cruzi antigens may provide the best overall protection for heterogeneous populations at risk for Chagas' disease. Other previously described antigens that might be considered for use in multicomponent T. cruzi vaccines include gp72, gp90, paraflagellar rod proteins, and members of the trans-sialidase superfamily (6, 13, 15, 37, 45, 52, 53, 62). The data presented here strongly support the inclusion of cruzipain as well in future multivalent T. cruzi vaccines.

Before any T. cruzi vaccine candidate can be used in phase I trials in humans, it will be important to complete detailed preclinical studies to ensure that the vaccine does not trigger immunopathologic mechanisms. We have not identified any toxic effects of immunizations with our recombinant cruzipain vaccines. Cruzipain-immunized mice developed protective immunity against T. cruzi challenges and lived normal life spans compared with uninfected and unimmunized mice. However, Giordanengo et al. recently reported that immunization with native cruzipain purified from parasite lysates can induce cardiac conduction abnormalities and have suggested that cruzipain-specific immunity may be important for the pathogenesis of chagasic cardiomyopathy (16). Although these authors present data indicating that native cruzipain immunization was associated with increased cardiac myosin-specific antibody responses, it is not clear that these myosin-specific antibodies were induced by cross-reactive cruzipain epitopes and it was not shown that the myosin-specific antibodies were causally related to the induction of cardiac abnormalities. The authors studied native cruzipain purified from parasite lysates. Native cruzipain could have caused proteolytic disruption of myocytes at the site of vaccination, releasing myosin into a milieu of potent inflammatory signals stimulated by complete Freund's adjuvant and leading to a breakdown of the normal state of myosin-specific B-cell tolerance. An additional possible explanation for their results is that contaminants copurified from parasite lysates with the native cruzipain, but not present in our purified recombinant-cruzipain preparations, may be responsible for the induction of myosin-specific antibodies. Furthermore, even if cruzipain-specific B-cell epitopes are cross-reactive with myosin, these cross-reactive epitopes are likely to be distinct from the cruzipain T-cell epitopes involved in the induction of protective immune responses. It is of critical importance for the potential use of cruzipain in T. cruzi vaccines to explore these different possibilities.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the American Heart Association—Missouri Affiliate (A.R.S.) and by National Institutes of Health grant AI34912-03 (D.F.H.).

We thank James McKerrow and Juan Engel for advice on recombinant protein purifications. We thank Julio Scharfstein for MAb 212BH6 and for advice on cruzipain expression. We thank Stan Wolf (Genetics Institute) for recombinant murine IL-12.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbas, A. K., K. M. Murphy, and A. Sher. 1996. Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature 383:787-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aida, Y., and M. J. Pabst. 1990. Removal of endotoxin from protein solutions by phase separation using Triton X-114. J. Immunol. Methods 132:191-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araujo, F. 1989. Development of resistance to Trypanosoma cruzi in mice depends on a viable population of L3T4+ (CD4+) T lymphocytes. Infect. Immun. 57:2246-2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnholdt, A. C. V., M. R. Piuvezam, D. M. Russo, A. P. C. Lima, R. C. Pedrosa, S. G. Reed, and J. Scharfstein. 1993. Analysis and partial epitope mapping of human T cell responses to Trypanosoma cruzi cysteinyl proteinase. J. Immunol. 151:3171-3179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aslund, L., J. Henriksson, O. E. Campetella, A. C. C. Frasch, U. Pettersson, and J. J. Cazzulo. 1991. The C-terminal extension of the major cysteine proteinase (cruzipain) from Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 45:345-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beard, C. A., R. A. Wrightsman, and J. E. Manning. 1988. Stage and strain specific expression of the tandemly repeated 90 kDa surface antigen gene family in Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 28:227-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellotti, G., E. A. Bocchi, A. V. de Moraes, M. L. Higuchi, M. Barbero-Marcial, E. Sosa, A. Esteves-Filho, R. Kalil, R. Weiss, A. Jatene, and F. Pileggi. 1996. In vivo detection of Trypanosoma cruzi antigens in hearts of patients with chronic Chagas' heart disease. Am. Heart 131:301-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradley, L. M., D. K. Dalton, and M. Croft. 1996. A direct role for IFN-gamma in regulation of Th1 cell development. J. Immunol. 157:1350-1358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandariz, S., A. Schijman, C. Vigliano, P. Arteman, R. Viotti, C. Beldjord, and M. J. Levin. 1995. Detection of parasite DNA in Chagas' heart disease. Lancet 346:1370-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campetella, O. E., J. Henriksson, L. Aslund, A. C. C. Frasch, U. Pettersson, and J. J. Cazzulo. 1992. The major cysteine proteinase (cruzipain) from Trypanosoma cruzi is encoded by multiple polymorphic tandemly organized genes located on different chromosomes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 50:225-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campetella, O. E., J. Martinez, and J. J. Cazzulo. 1990. A major cysteine proteinase is developmentally regulated in Trypanosoma cruzi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 67:145-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cazzulo, J. J., R. Couso, A. Raimondi, C. Wernstedt, and U. Hellman. 1989. Further characterization and partial amino acid sequence of a cysteine proteinase from Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 33:33-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costa, F., G. Franchin, V. L. Pereira-Chioccola, M. Ribeirao, S. Schenkman, and M. M. Rodrigues. 1998. Immunization with a plasmid DNA containing the gene of trans-sialidase reduces Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice. Vaccine 16:768-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eakin, A. E., A. A. Mills, G. Harth, J. H. McKerrow, and C. S. Craik. 1992. The sequence, organization, and expression of the major cysteine protease (cruzain) from Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Biol. Chem. 267:7411-7420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujimura, A. E., S. S. Kinoshita, V. L. Pereira-Chioccola, and M. M. Rodrigues. 2001. DNA sequences encoding CD4+- and CD8+-T-cell epitopes are important for efficient protective immunity induced by DNA vaccination with a Trypanosoma cruzi gene. Infect. Immun. 69:5477-5486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giordanengo, L., C. Maldonado, H. W. Rivarola, D. Iosa, N. Girones, M. Fresno, and S. Gea. 2000. Induction of antibodies reactive to cardiac myosin and development of heart alterations in cruzipain-immunized mice and their offspring. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:3181-3189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green, L. C., D. A. Wagner, J. Glogowski, P. L. Skipper, J. S. Wishnok, and S. R. Tannenbaum. 1982. Analysis of nitrate, nitrite, and [15N]nitrate in biological fluids. Anal. Biochem. 126:131-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoft, D. F., P. L. Farrar, K. Kratz-Owens, and D. Shaffer. 1996. Gastric invasion by Trypanosoma cruzi and induction of protective mucosal immune responses. Infect. Immun. 64:3800-3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoft, D. F., K. S. Kim, K. Otsu, D. R. Moser, W. J. Yost, J. H. Blumin, J. E. Donelson, and L. V. Kirchhoff. 1989. Trypanosoma cruzi expresses diverse repetitive protein antigens. Infect. Immun. 57:1959-1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoft, D. F., R. G. Lynch, and L. V. Kirchhoff. 1993. Kinetic analysis of antigen-specific immune responses in resistant and susceptible mice during infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Immunol. 151:7038-7047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoft, D. F., A. R. Schnapp, C. S. Eickhoff, and S. T. Roodman. 2000. Involvement of CD4+ Th1 cells in systemic immunity protective against primary and secondary challenges with Trypanosoma cruzi. Infect. Immun. 68:197-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Humphrey, J. S., T. S. McCormick, and E. C. Rowland. 1997. Parasite antigen-induced IFN-gamma and IL-4 production by cells from pathopermissive and pathoresistant strains of mice infected with Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Parasitol. 83:533-536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones, E. M., D. G. Colley, S. Tostes, E. R. Lopes, C. L. Vnencak-Jones, and T. L. McCurley. 1993. Amplification of a Trypanosoma cruzi DNA sequence from inflammatory lesions in human chagasic cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 48:348-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalil, J., and E. Cunha-Neto. 1996. Autoimmunity in Chagas disease cardiomyopathy: fulfilling the criteria at last? Parasitol. Today 12:396-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang, H. Y., J. Srinivasan, and R. Curtiss III. 2002. Immune responses to recombinant pneumococcal PspA antigen delivered by live attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine. Infect. Immun. 70:1739-1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kierszenbaum, F., and J. G. Howard. 1976. Mechanisms of resistance against experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection: the importance of antibodies and antibody-forming capacity in the Biozzi high and low responder mice. J. Immunol. 116:1208-1211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krettli, A. U., and Z. Brener. 1982. Resistance against Trypanosoma cruzi associated to anti-living trypomastigote antibodies. J. Immunol. 128:2009-2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar, S., and R. L. Tarleton. 2001. Antigen-specific Th1 but not Th2 cells provide protection from lethal Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice. J. Immunol. 166:4596-4603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lane, J. E., D. Olivares-Villagomez, C. L. Vnencak-Jones, T. L. McCurley, and C. E. Carter. 1997. Detection of Trypanosoma cruzi with the polymerase chain reaction and in situ hybridization in infected murine cardiac tissue. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 56:588-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lima, A. P. C., D. C. Tessier, D. Y. Thomas, J. Scharfstein, A. C. Storer, and T. Vernet. 1994. Identification of new cysteine protease gene isoforms in Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 67:333-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lima-Martins, M. V. C., G. A. Sanchez, A. U. Krettli, and Z. Brener. 1985. Antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity against Trypanosoma cruzi is only mediated by protective antibodies. Parasite Immunol. 7:367-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez, J., O. Campetella, A. C. C. Frasch, and J. J. Cazzulo. 1991. The major cysteine proteinase (cruzipain) from Trypanosoma cruzi is antigenic in human infections. Infect. Immun. 59:4275-4277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinez, J., O. E. Campetella, A. C. C. Frasch, and J. J. Cazzulo. 1993. The reactivity of sera from chagasic patients against different fragments of cruzipain, the major cysteine proteinase from Trypanosoma cruzi, suggests the presence of defined antigenic and catalytic domains. Immunol. Lett. 35:191-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez, J., and J. J. Cazzulo. 1992. Anomolous electrophoretic behaviour of the major cysteine proteinase (cruzipain) from Trypanosoma cruzi in relation to its apparent molecular mass. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 95:225-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehrotra, P. T., D. Wu, J. A. Crim, H. S. Mostowski, and J. P. Siegel. 1993. Effects of IL-12 on the generation of cytotoxic activity in human CD8+ T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 151:2444-2452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meirelles, M. N. L., L. Juliano, E. Carmona, S. G. Silva, E. M. Costa, A. C. M. Murta, and J. Scharfstein. 1992. Inhibitors of the major cysteinyl proteinase (GP57/51) impair host cell invasion and arrest the intracellular development of Trypanosoma cruzi in vitro. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 52:175-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Millar, A. E., M. Wleklinski-Lee, and S. J. Kahn. 1999. The surface protein superfamily of Trypanosoma cruzi stimulates a polarized Th1 response that becomes anergic. J. Immunol. 162:6092-6099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muñoz-Fernández, M. A., M. A. Fernández, and M. Fresno. 1992. Synergism between tumor necrosis factor-α and interferon-γ on macrophage activation for the killing of intracellular Trypanosoma cruzi through a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Eur. J. Immunol. 22:301-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murta, A. C. M., V. C. M. Leme, S. R. Milani, L. R. Travassos, and J. Scharfstein. 1988. Glycoprotein GP57/51 of Trypanosoma cruzi: structural and conformational epitopes defined with monoclonal antibodies. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 83S:419-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murta, A. C. M., P. M. Perechini, T. Souto-Padron, W. De Souza, J. A. Guimaraes, and J. Scharfstein. 1990. Structural and functional identification of GP57/51 antigen of Trypanosoma cruzi as a cysteine proteinase. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 43:27-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakayama, K., S. M. Kelly, and R. Curtiss III. 1988. Construction of an asd+ expression-cloning vector: stable maintenance and high level expression of cloned genes in a Salmonella vaccine strain. Bio/Technology 6:693-697. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nascimento, A. E., and W. De Souza. 1996. High resolution localization of cruzipain and Ssp4 in Trypanosoma cruzi by replica staining label fracture. Biol. Cell 86:53-58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nickell, S. P., A. Gebremichael, R. Hoff, and M. H. Boyer. 1987. Isolation and functional characterization of murine T cell lines and clones specific for the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Immunol. 138:914-921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nickell, S. P., M. Keane, and M. So. 1993. Further characterization of protective Trypanosoma cruzi-specific CD4+ T-cell clones: T helper type 1-like phenotype and reactivity with shed trypomastigote antigens. Infect. Immun. 61:3250-3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nogueira, N., S. Chaplan, J. D. Tydings, J. Unkeless, and Z. Cohn. 1981. Trypanosoma cruzi surface antigens of blood and culture forms. J. Exp. Med. 153:629-639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reis, M. M., M. D. Higuchi, L. A. Benvenuti, V. D. Aiello, P. S. Gutierrez, G. Belloti, and F. Pileggi. 1997. An in situ quantitative immunohistochemical study of cytokines and IL-2R+ in chronic human Chagasic myocarditis: correlation with the presence of myocardial Trypanosoma cruzi antigens. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 83:165-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rottenberg, E. M., A. Riarte, L. Sporrong, J. Altcheh, P. Petray, A. M. Ruiz, H. Wigzell, and A. Orn. 1995. Outcome of infection with different strains of Trypanosoma cruzi in mice lacking CD4 and/or CD8. Immunol. Lett. 45:53-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 49.Scharfstein, J., M. Schechter, M. Senna, J. M. Peralta, L. Mendonca-Previato, and M. A. Miles. 1986. Trypanosoma cruzi: characterization and isolation of a 57/51,000 m.w. surface glycoprotein (GP57/51) expressed by epimastigotes and bloodstream trypomastigotes. J. Immunol. 137:1336-1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schneider, J., S. C. Gilbert, T. J. Blanchard, T. Hanke, K. J. Robson, C. M. Hannan, M. Becker, R. Sinden, G. L. Smith, and A. V. Hill. 1998. Enhanced immunogenicity for CD8+ T cell induction and complete protective efficacy of malaria DNA vaccination by boosting with modified vaccinia virus Ankara. Nat. Med. 4:397-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seder, R. A., and W. E. Paul. 1994. Acquisition of lymphokine-producing phenotype by CD4+ cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 12:635-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sepulveda, P., M. Hontebeyrie, P. Liegeard, A. Mascilli, and K. A. Norris. 2000. DNA-based immunization with Trypanosoma cruzi complement regulatory protein elicits complement lytic antibodies and confers protection against Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Infect. Immun. 68:4986-4991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Snary, D. 1983. Cell surface glycoproteins of Trypanosoma cruzi: protective immunity in mice and antibody levels in human chagasic sera. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 77:126-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Souto-Padron, T., O. E. Campetella, J. J. Cazzulo, and W. De Souza. 1990. Cysteine proteinase in Trypanosoma cruzi: immunocytochemical localization and involvement in parasite-host cell interaction. J. Cell Sci. 96:485-490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stern, A. S., F. J. Podlaski, J. D. Hulmes, Y. E. Pan, P. M. Quinn, A. G. Wolitzky, P. C. Familletti, D. L. Stremlo, T. Truitt, R. Chizzonite, and M. K. Gately. 1990. Purification to homogeneity and partial characterization of cytotoxic lymphocyte maturation factor from human B-lymphoblastoid cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:6808-6818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tarleton, R. L. 1990. Depletion of CD8+ T cells increases susceptibility and reverses vaccine-induced immunity in mice infected with Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Immunol. 144:717-724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tarleton, R. L., M. J. Grusby, M. Postan, and L. H. Glimcher. 1996. Trypanosoma cruzi infection in MHC-deficient mice: further evidence for the role of both class I- and class II-restricted T cells in immune resistance and disease. Int. Immunol. 8:13-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tarleton, R. L., B. H. Koller, A. Latour, and M. Postan. 1992. Susceptibility of B2-microglobulin-deficient mice to Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Nature 356:338-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tarleton, R. L., J. Sun, L. Zhang, and M. Postan. 1994. Depletion of T-cell subpopulations results in exacerbation of myocarditis and parasitism in experimental Chagas' disease. Infect. Immun. 62:1820-1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tarleton, R. L., L. Zhang, and M. O. Downs. 1997. “Autoimmune rejection” of neonatal heart transplants in experimental Chagas disease is a parasite-specific response to infected host tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:3932-3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.W. H. O. Expert Committee. 1991. Control of Chagas disease (W. H. O. technical report series 811). World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [PubMed]

- 62.Wizel, B., M. Nunes, and R. L. Tarleton. 1997. Identification of Trypanosoma cruzi trans-sialidase family members as targets of protective CD8+ TC1 responses. J. Immunol. 159:6120-6130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]